Abstract

Transcription factor NFκB and the serine/threonine kinase Akt play critical roles in mammalian cell survival signaling and have been shown to be activated in various malignancies including prostate cancer (PCA). We have developed an analogue of curcumin called 4-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzoic acid methyl ester (HMBME) that targets the Akt/NFκB signaling pathway. Here, we demonstrate the ability of this novel compound to inhibit the proliferation of human and mouse PCA cells. HMBME-induced apoptosis in these cells was tested by using multiple biochemical approaches, in addition to morphological analysis. Overexpression of constitutively active Akt reversed the HMBME-induced growth inhibition and apoptosis, illustrating the direct role of Akt signaling in HMBME-mediated growth inhibition and apoptosis. Further, investigation of the molecular events associated with its action in LNCaP cells shows that: 1) HMBME reduces the level of activated form of Akt (phosphorylated Akt); and 2) inhibits the Akt kinase activity. Further, the transcriptional activity of NFκB, the DNA-binding activity of NFκB, and levels of p65 were all significantly reduced following treatment with HMBME. Overexpression of constitutively active Akt, but not the kinase dead mutant of Akt, activated the basal NFκB transcriptional activity. HMBME treatment had no influence on this constitutively active Aktaugmented NFκB transcriptional activity. These data indicate that HMBME-mediated inhibition of Akt kinase activity may have a potential in suppressing/decreasing the activity of major survival/antiapoptotic pathways. The potential use of HMBME as an agent that targets survival mechanisms in PCA cells is discussed.

Keywords: Akt kinase, apoptosis, cell survival, curcumin derivative, prostate cancer management

Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCA) is the most common lethal malignancy in men and is responsible for about 31,000 deaths annually in the United States [1]. Adenocarcinoma of the prostate is generally slow-growing; nonetheless, the morbidity from the disease is high because of urologic impairment and painful bone metastasis. Because PCA incidence increases with advancing age, it is expected that this malignancy will become an increasingly greater problem as worldwide life expectancy improves. Most PCA patients are diagnosed with advanced stage of metastatic disease for which there is no effective therapy available at this time [2–4]. Therefore, there is a continuous demand for identification and development of nontoxic agents for the management of PCA. Preventing or inhibiting the progression of PCA by dietary and medicinal phytochemicals is currently gaining substantial interest. In particular, agents that 1) interfere with tumor development by slowing down disease progression and 2) improve the quality of life and have exceptional clinical value are gaining ground. Most plants contain phenolic/polyphenolic antioxidants such as flavonoids, hydroxy cinnamic acid derivatives, and simple phenols and phenolic acids [5,6].

Curcumin (diferuloylmethane) is the major active yellow pigment of the rhizome of the turmeric plant that is widely used as a food-flavoring agent by Asians. Curcumin has been shown to have antiproliferative and antioxidant properties in human tumor cell cultures and to prevent cancer in many animal models [7–17]. Recently, Perkins et al. [17] showed chemopreventive activity of curcumin in a mouse model that is germane to human colorectal cancer involving Apc mutations. Thus, the use of curcumin or its related compounds in the diet can potentially decrease the susceptibility to cancer-causing agents. This may be one of the reasons for the observed lower incidence of PCA seen in Asians. Consistent with this idea, Dorai et al. [18] showed growth inhibition of both androgen-responsive and androgen-independent PCA cells treated with curcumin through the induction of apoptosis. Subsequently, the same group demonstrated that use of 2% curcumin in the diet strongly inhibited the growth of LNCaP PCA cells in athymic nude mice [19]. In contrast, Imaida et al. [20] reported no chemopreventive effect of curcumin (500 ppm) against DMAB- or PhIP-induced prostate carcinogenesis. Although several other factors including organ specificity could contribute to this lack of chemopreventive effect, it is very possible that this may be due to low absorption or rapid metabolism of curcumin in this model.

Curcumin exhibits its antiproliferative activities in cell culture studies in the range of 10 to 100 µM. However, the bioavailability of curcumin has been shown to be low in rodents [21–25]. For example, administration of 1 g/kg body weight of mouse yielded a plasma level of 0.5 µM (0.06% absorption). In addition, oral dosing of humans with 4 to 8 g of curcumin showed plasma levels of about 0.41 to 1.75 µM (about 0.004–0.008% absorption). Such low plasma levels may not bring forth the optimal chemopreventive and/or therapeutic effect. It is also very likely that curcumin is biotransformed to products that are responsible for, or contribute to, this effect. Although the metabolism of curcumin in humans is poorly understood, curcumin's bioavailability may be poor in humans based on the recent study in colorectal cancer patients [22–25]. These observations indicate that the prospective clinical utility of curcumin is seriously limited.

We have synthesized several smaller derivatives of curcumin that retain its polar functionality [26]. These analogues lack the dieneone structure of curcumin and, hence, they are not subjected to the type of reductive metabolism documented with curcumin in vivo. These derivatives are more soluble than curcumin while potentially retaining curcumin's favorable biologic activities. After testing these compounds for their potential to inhibit growth of PCA cells, we determined 4-hydroxy-3-methoxy benzoic acid methyl ester (HMBME) to be a lead compound for further studies. The structure of HMBME is shown below (Figure 1). In this study, we investigated the potential of HMBME to inhibit the growth of various PCA cells and the underlying mechanisms involved. In addition, we show that HMBME induces apoptosis in LNCaP cells by targeting the Akt/NFκB survival signaling pathway.

Figure 1.

Structure of HMBME.

Materials and Methods

Synthesis of 4-Hydroxy-3-Methoxybenzoic Acid Methyl Ester (HMBME)

Two grams of 4-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzoic acid (Aldrich, Milwaukee, WI) was dissolved in 60 ml of dry methanol. After adding 5mg of p-toluenesulfonic acid monohydrate (Aldrich), the reaction was refluxed for 24 hours. Following evaporation of the solvent in vacuo, the residue was purified by flash silica gel chromatography using hexane/ethyl acetate (70:30) as eluting solvent. The purified fractions were identified by thin layer chromatography on silica gel. These fractions were combined and the solvent was evaporated in vacuo to give HMBME. The purity was checked by gas chromatography mass spectroscopy, which showed major peaks at m/z 182 (90) and 151 (100). Proton NMR in CDCl3: δ 3.804 (s, 3H); δ 3.835 (s, 3H); δ 6.187 (broad s, 1H); δ 6.844 and 6.865 (d, 1H); δ 7.459 and 7.463 (d, 1H); and δ 7.539, 7.544, 7.560, and 7.564 (q, 1H).

Cell Lines

Human PCA cell lines including androgen-responsive (LNCaP) and androgen-independent (DU145) were grown as described earlier [27]. In addition, a human benign prostatic hyperplasia cell line (BPH-1) was obtained from Dr. Gary Millers' laboratory (University of Colorado Health Sciences Center, Denver, CO). BPH-1 is an immortalized cell line derived from primary prostatic epithelial cells using SV40 lager T antigen [28]. Due to expression of SV 40T antigen (that inactivates p53 and Rb), this cell line is susceptible to genetic alterations during carcinogenesis process and can be considered tumorigenic. TRAMP cell lines obtained from Dr. Norman Greenberg (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX) were grown as described earlier [29]. Nontumorigenic fibroblast cell line GM0637 was obtained from Dr. David Mitchell (The University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, Smithville, TX) and was grown as described elsewhere.

Cell Viability and Proliferation Assay

Actively growing cells (LNCaP, DU145, GM-0637, BPH-1, and TRAMP cell lines) were plated in 96-well plates at a density of 4 x 103 cells/well in five replicates. After 24 hours in a 37°C incubator with 5% CO2, cells were treated with the indicated concentration of HMBME. Control cells received only the vehicle (DMSO). Cell viability was determined by the trypan blue exclusion assay. Cell growth was monitored every 24 hours using the CellTiter96 Aqueous One solution assay containing a tetrazolium compound (Promega, Madison, WI).

Colony Formation Assay

Logarithmically growing cells (LNCaP) were trypsinized and plated at a density of 13,000 cells/ml in 0.5% agarose plates in triplicate. Plates were prepared fresh by adding 0.5 g of agar (FMC 50102) to 100 ml of complete growth media and by incubating in a water bath at 44°C. Two milliliters of this agarose was evenly layered in six-well plates and allowed to solidify for 30 minutes. Two milliliters of complete media containing 0.5% agar was added to 40,000 cells. After mixing, 1 ml of media containing cells was poured on top of the 0.5% media in the six-well plate. A plate containing no cells was used as a negative control. After 14 days, cells were stained with 0.02% p-iodonitrotetrazolium. After 5 hours, the colonies that stained dark pink were counted in 10 different fields from each well.

Flow Cytometric Analysis

Logarithmically growing (LNCaP) cells were plated at a density of 1 x 105 in 60-mm dishes as described above. Cells at 70% to 80% confluency were treated at time 0 with 25 µM HMBME or solvent control for 24 hours. Cells were harvested by trypsinization and the cell pellet was resuspended in 1 ml of Krishan stain containing 1.1 mg/ml sodium citrate, 46 µg/ml propidium iodide, 0.01% NP40, and 10 µg/ml RNase [27]. Flow cytometric analysis was preformed at the Flow Cytometry core facility of the University of Colorado Comprehensive Cancer Center (Denver, CO) using a Coulter XL flow cytometer (Beckman-Coulter, Hialeah, FL). Data were analyzed using Modfit LT from Verity Software House (Topsham, Maine).

Detection of Apoptosis

Logarithmically growing cells (LNCaP) were plated at a density of 1 x 105 in 60-mm dishes as described above. At 70% to 80% confluence, cells were treated with HMBME (25 µM for 24 hours). Following incubation, both the adherent and floating cells were collected by trypsinization for detection of apoptosis using morphologic analysis, FITC-Annexin, and acridine orange staining [30].

FITC-Annexin

During the initial stages of apoptosis, cells lose their phospholipid membrane asymmetry and phosphotidylserine (PS) is exposed to the cell surface. This can be monitored by using Annexin V, which is a phospholipid-binding protein with high affinity for PS. Because translocation of PS occurs not only during apoptosis but also during necrosis, PI is used to distinguish between late and early stages of apoptosis. We used the Annexin V-FITC kit (Medical and Biological Laboratories, Watertown, MA) to quantify apoptosis in LNCaP cells treated with HMBME (25 µM for 24 hours) using flow cytometry as per manufacturer's recommendations.

Acridine Orange/Ethidium Bromide Staining

Briefly, 25 µl of dye mixture (acridine orange and ethidium bromide, 100 µg each in 1 ml) was mixed with 25 µl of cell suspension and was examined under a fluorescent microscope with a blue filter. Viable cells (green) and apoptotic cells containing fragmented nuclei (red) were counted and the percentage of apoptotic cells was then calculated. Cells were counted in at least five different fields in triplicate samples.

Transfections and Transient Expression Assays

Transient transfections were performed in LNCaP cells using a lipofectin reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Briefly, pNFκB reporter plasmid (1 µg/well) and pRL-TK plasmid (50 ng/well; renilla luciferase for normalization) were incubated with the lipofectin reagent for 30 minutes at room temperature. The DNA-lipofectin mixture was then added to the cells and incubated for 48 hours. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were treated with HMBME (25 µM) for 2 hours. Following HMBME treatment, cells were collected and lysed in passive lysis buffer (PLB) as per manufacturer's recommendations (Promega). Cell lysate was cleared from debris by centrifuging at 10,000 rpm for 5 minutes at 4°C. Luciferase activity was assayed using Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega) in duplicate samples containing equal amounts of protein. The assay mixture contained 20 µl of cell lysate and 50 µl of firefly luciferase measuring buffer (LARII). Firefly luciferase activity was measured on a Genios Tecan luminometer (Phenix Research Products, Hayward, CA). After measuring the firefly luciferase activity, the reaction mixture was added to 50 µl of renilla luciferase measuring buffer (Stop and Glow) and renilla luciferase activity was measured. Renilla luciferase activity was used to normalize the transfection efficiency. Results are expressed as the ratio of firefly luciferase/renilla luciferase at equal amounts of protein. For cotransfection experiments, the super repressor IκBα mutant expression vector (1 µg/well), constitutively active Akt (1 µg/well), and kinase dead mutant of Akt (1 µg/well) were included along with the pNFκB reporter plasmid.

To determine the effect of overexpression of Akt on HMBME-induced growth inhibition and apoptosis, subconfluent LNCaP cells were transfected with either pCMVMyr-Akt (an activated form of Akt with the Src myristoylation signal fused in-frame to the c-Akt coding sequence) or control vector (pCMV) using Lipofectamin (Invitrogen) as described above. Forty-eight hours following transfection, cells were treated either with 25 µM HMBME or solvent control. Both floating and adherent cells were collected after 2 hours of treatment and assessed for 1) morphologic alterations; 2) cell viability by trypan blue exclusion assay; and 3) apoptosis by acridine orange//ethidium bromide staining [30].

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assays (EMSAs)

Gel shift assays were done as described elsewhere [31–33]. Double-stranded NFκB oligonucleotide was end-labeled with γ-p32-ATP using T4 polynucleotide kinase. Nuclear extracts were incubated with the radiolabled probe in binding buffer (containing 4 mM Tris-HCl, 12 mM Hepes, pH 7.9, 60 mM KCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, and 12% glycerol) for 20 minutes at room temperature in a final volume of 20 µl. After incubation, samples were fractionated on a 4% polyacrylamide gel in 0.25 x TBE at 4°C. Following electrophoresis, the gel was dried and autoradiographed. For competition studies, the radiolabled probe was mixed with 100-fold molar excess of unlabelled double-stranded synthetic NFκB oligonucleotide (homologous competition) and Sp1 (for heterologous competition) for 20 minutes prior to the addition of extracts. For gel supershift experiments, the nuclear extracts were preincubated for 30 minutes with either normal rabbit serum (NRS) or p65 or p50 antibody and used in EMSA as described [33].

Preparation of Cell Extracts

Actively growing LNCaP Cells were treated with 25 µM HMBME for indicated time periods (15 minutes, 30 minutes, 60 minutes, 2 hours, and 24 hours). Following treatment, cells were lysed in a buffer containing (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150mM NaCl, 0.5% NP40, 50mMNaF, 1 mMNa VO4, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 25 µg/ml leupeptin, 25 µg/ml aprotinin, 25 µg/ml pepstatin, and 1 mM DTT). After passing the lysate through a 25-gauge needle, cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 30 min.

Nuclear Extracts

Nuclear extracts were prepared according to the method of Dignam and protein content of the extracts was determined by the method of Bradford as described [32].

Western Blotting

Equal amounts of extracts were fractionated on a 10% SDS polyacrylamide gel. Following electrophoresis, proteins were electrophoretically transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The blotted membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat dried milk in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20 (blocking solution), and incubated with indicated polyclonal antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA; Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA) followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antirabbit IgG antibody (Sigma) in blocking solution. Bound antibody was detected by enhanced chemiluminescence using Supersignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate, following the manufacturer's directions (Pierce, Rockford, IL). All the blots were stripped and reprobed with β-actin to ensure equal loading of protein.

Akt Kinase Assay

Endogenous Akt kinase was measured in the extracts from control and HMBME-treated LNCaP cells using Akt kinase assay kit (Cell Signaling Technology). Briefly, cell extracts were incubated with immobilized Akt monoclonal antibody overnight. Following extensive washes, kinase reaction was performed in the presence of 200 µM cold ATP and GSK-3 substrate. Phosphorylation of GSK-3 was measured by Western blotting using phospho-GSK-3 antibody.

Results and Discussion

HMBME Inhibits the Growth of Human and Mouse PCA Cells without Influencing the Growth of Nontumorigenic Fibroblasts

The effect of HMBME was tested on the growth of benign prostate hyperplasia (BPH-1), androgen-sensitive human PCA cells (LNCaP), and androgen-independent (DU145) human PCA cells. Trypan blue exclusion assay and Cell-Titer96 Aqueous One solution assay containing a tetrazolium compound (Promega) were used to determine the cell proliferation, as described previously [27]. The assay is based on the principle that actively growing cells generate reducing equivalents, such as NADH, that are necessary for the cells to reduce the tetrazolium compound to a formazan product. This was detected by measuring the absorbance at 570 nm using a plate reader. An increase in the conversion of the MTS tetrazolium compound to the colored formazan product (indicated by increased absorbance) provides a relative measure of viable cell number, whereas a decrease provides a relative measure of cell death over a period of time. As shown in Figure 2A, incubation of cells (LNCaP, DU145, or BPH-1) with HMBME showed a dose-dependent decrease in the cell proliferation. This is consistent with the data obtained using trypan blue exclusion assay (data not shown). In addition, we tested the effect of HMBME on mouse PCA cell lines. These prostate tumor cell lines designated as TRAMP C2 and TRAMP C3 are derived from different stages of PCA progression from transgenic adenocarcinoma of mouse prostate (TRAMP) mice and express androgen receptors (ARs). As shown in Figure 2B, HMBME was effective in inhibiting the growth of both cell lines.

Figure 2.

(A) Effect of HMBME on proliferation of androgen-responsive (LNCaP), androgen-independent (DU145), benign prostatic epithelial (BPH-1), and nontumorigenic fibroblasts (GM0637). Cells were plated in 96-well plates as described in Materials and Methods section and treated with indicated concentrations of either HMBME or solvent control. Cell proliferation was measured by CellTiter96 Aqueous One solution assay at a 72-hour time point by determining the absorbance at 570 nm using SpectraMaxPlus plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). The data shown here are an average ± SD of five replicate wells and are representative of four independent experiments. (B) Effect of HMBME on the proliferation of TRAMP cell lines. The experimental procedure was the same as described in legends for (A). (C) Effect of HMBME on colonyforming ability of LNCaP cells. Cells were plated in triplicate in 35-mm dishes on 0.5% agarose-containing media as described in Materials and Methods section. Following 14-day incubation, cells were stained with 0.5 ml of 0.02% p-iodonitrotetrazolium and colonies were counted in 10 different fields from each plate. The results are expressed as mean ± SD of five replicate wells and are representative of two independent experiments.

Further, we compared the effect of HMBME on the growth of GM0637, a nontumorigenic fibroblast cell line. As shown in Figure 2A, 25 µM HMBME (the concentration that caused approximately 40% growth inhibition in PCA cell lines) did not affect the growth of these cells. In contrast, 25 µM curcumin (parent compound) inhibited the growth of GM0637 cells (data not shown). In order to produce comparable inhibition in these cells, a concentration of more than 50 µM HMBME was necessary. Because GM0637 cells are not prostatic in origin, we cannot draw any conclusions regarding the specificity of HMBME towards tumor cells; however, these results indicate that HMBME inhibits proliferation of tumor cells more efficiently compared to nontumorigenic fibroblast cells.

HMBME Inhibits the Anchorage-Independent Growth of LNCaP Cells

We tested the effect of HMBME on the anchorageindependent growth of LNCaP cells as assayed by their ability to grow as colonies in soft agar. As shown in Figure 2C, there was a dose-dependent decrease in the colony-forming ability of LNCaP cells following exposure to HMBME. Inclusion of 25 µM HMBME in the soft agar assay inhibited colony formation by more than 50%. These data indicate that anchorage-independent growth of LNCaP cells on soft agar was significantly inhibited by HMBME that is consistent with the above cell proliferation data. In contrast, untreated cells continued to proliferate during the course of the experiment.

HMBME Induces G1-Specific Cell Cycle Block and Apoptosis in LNCaP Cells

To examine the effect of HMBME on cell proliferation, we performed cell cycle analysis in which cellular DNA content was measured in propidium iodide-stained cells by flow cytometry. As shown in Figure 3A, incubation of LNCaP cells with 25 µM HMBME for 24 hours blocked cells in G1-phase with concomitant decrease in S-phase population of cells. HMBME treatment had no significant effect on the population of cells in G2/M-phase. Figure 3A is a graph that shows an average of three independent experiments and Figure 3B is a representative histogram of flow analysis.

Figure 3.

Effect of HMBME on cell cycle distribution in LNCaP cells. LNCaP cells were treated with either DMSO alone or with 25 µM HMBME for 24 hours as described in Materials and Methods section. Following treatment, cells were harvested, washed with PBS, and then resuspended in 1 ml of Krishan stain containing 1.1 mg/ml sodium citrate, 46 µg/ml propidium iodide, 0.01% of NP40, and 10 µg/ml RNase. Data were analyzed using Modfit LT (panel B). Alterations in the distribution of cells in different phases are also shown as a graph (panel A). This is an average ± SD of three independent experiments.

HMBME Promotes Apoptosis in LNCaP Cells

Actively growing LNCaP cells were treated either with DMSO (solvent control) alone or 25 µM HMBME for different time points (24, 48, and 72 hours). Cells were examined microscopically every 24 hours for morphologic changes associated with treatment. As shown in Figure 4A, significant changes in the morphology including blebbing, condensation of the nuclear material, rounding of cells, and detachment from the dishes were seen in cells treated with HMBME. In addition, we observed cells with granular appearance. All of these are characteristic features of apoptosis. Vehicle-treated cells remain unchanged. Photomicrographs shown here were taken by phase contrast microscopy at x 40 magnification following 24 hours of treatment. These data indicate that the suppression of cell growth in LNCaP cells is associated with morphologic alterations consistent with induction of apoptosis. We confirmed the induction of apoptosis using additional independent approaches, as discussed in Materials and Methods section. The two-dimensional plots shown in Figure 4B display green fluorescence (Annexin binding) on the X-axis and orange fluorescence (PI uptake) on the Y-axis. Cells in the upper left quadrant with low Annexin and high PI staining represent necrotic cells; cells in the upper right quadrant with high Annexin and high PI staining represent late apoptotic cells; cells in the lower left quadrant with low Annexin and low PI staining represent viable cells; and cells in the lower right quadrant with high Annexin and low PI staining represent early apoptotic cells. As shown in Figure 4B, untreated cells show less than 10% spontaneous apoptosis; however, incubation with HMBME (for 24 hours) induced apoptosis in about 30% of the cells. This is also consistent with results obtained using acridine orange/ethidium bromide staining that showed approximately 30% of cells undergoing apoptosis (Figure 4C). The same concentration of HMBME inhibited the colony-forming ability of LNCaP cells by more than 50% (Figure 2C). These differences could be due to sensitivity of the techniques. These data using different biochemical approaches clearly demonstrate that HMBME inhibits the growth of LNCaP cells through induction of apoptosis.

Figure 4.

(A) Morphologic alterations of LNCaP cells following HMBME treatment. LNCaP cells were treated with either DMSO or with different concentrations of HMBME (5, 25, and 50 µM) for 24 hours. Photomicrographs of these cells were taken by phase contrast microscopy using a Nikon Microscope with a digital camera system Coolpix 995 at a magnification of 20 x (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). The picture shown here shows cells treated with 25 µM HMBME for 24 hours. Arrows indicate apoptotic cells. (B and C) Induction of apoptosis following treatment with HMBME. Cells were treated with HMBME (25 µM for 24 hours) and induction of apoptosis was detected by FITC-Annexin staining through flow cytometry and acridine/orange staining. Both the adherent and floating cells were collected by trypsinization for quantification of apoptosis as described in Materials and Methods section. A representative graph of FITC-Annexin is shown (B). Data shown for acridine orange/ethidium bromide staining are average ± SD of two independent experiments conducted in triplicate. Cells were counted in four different fields for each sample (panel C).

Modulation of Cell Survival Signaling Components Following HMBME Treatment

The observed decreased cell proliferation could be due to modulation of cell survival signaling pathway. It has been well established that the antiapoptotic kinase Akt and antiapoptotic factor NFκB play a critical role in the cell survival signaling pathway in a variety of cancers including PCA [34–40]. Akt is a well-characterized serine/threonine kinase that promotes cell survival and is activated in response to many different growth factors. Activation of Akt signaling pathway promotes cell survival by inhibiting apoptosis through phosphorylation of the proapoptotic protein BAD and other proteins. In a recent study, Malik et al. [41] have shown an increased expression of phospho-Akt in human PCA specimens indicating the activation of cell survival signaling pathways and suppression of apoptosis. This result is consistent with the observation that PTEN, a negative regulator of Akt, is altered and inactive in many types of cancers including PCA [42,43]. PTEN is also the most widely mutated tumor suppressor gene in PCA and may also contribute to the acquisition of the metastatic phenotype [44]. In addition, activated Akt can also exert its antiapoptotic effects through regulation of transcription factors such as NFκB [45,46]. The transcription factor NFκB has been shown to play an important role in coordinating the control of apoptotic cell death, which either promotes or inhibits apoptosis depending on the cell type and the apoptotic stimuli [34,35]. Overexpression of NFκB has been shown to be associated with various malignancies including PCA. Activation of NFκB has been shown to be associated with decreased levels of apoptosis in vitro and mice lacking p65 exhibit increased levels of apoptosis [47–49]. Similarly, although staining was heterogeneous, tumor samples obtained from radical prostatectomy patients showed activation of NFκB [49]. Thus, targeting Akt/NFκB signaling is a potential strategy for suppression of cancer cell survival as a means of cancer management. With this background, we have hypothesized that HMBME may induce apoptosis through inhibition of Akt/NFκB-mediated cell survival signaling pathway.

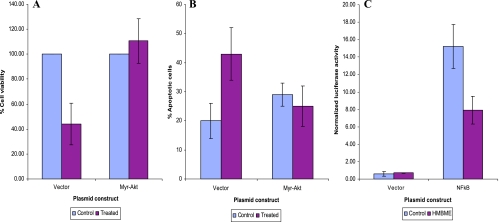

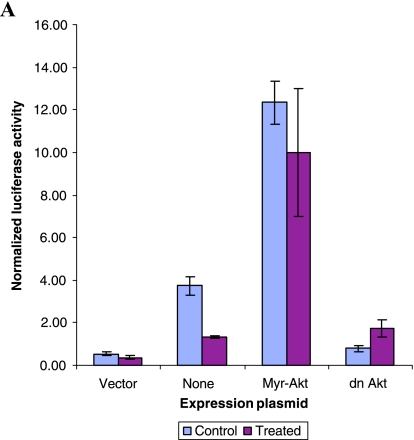

Constitutive Expression of Akt Protects LNCaP Cells from HMBME-Induced Growth Inhibition and Apoptosis

To show that HMBME-induced growth inhibition was mediated through the inhibition of Akt activation, transient transfections were performed using either pCMVMyrAkt or control vector (pCMV), as described in Materials and Methods section. As shown in Figure 5A, HMBME treatment inhibited the growth of LNCaP cells transfected with control vector that shows HMBME's growth-inhibitory effect and is consistent with the above cell proliferation data. In contrast, overexpression of constitutively active Akt protected LNCaP cells from the growth-inhibitory activity of HMBME. Although these data demonstrate a critical role for Akt signaling in HMBME-induced growth inhibition, it does not prove the involvement of Akt signaling in HMBME-induced apoptosis.

Figure 5.

(A) Overexpression of constitutively active Akt protects LNCaP cells from HMBME-induced cell growth inhibition. Subconfluent LNCaP cells were transfected with either pCMVMyrAkt (an activated form of Akt with the Src myristoylation signal fused in-frame to the c-Akt coding sequence) or control vector (pCMV) using Lipofectamin (Invitrogen) in triplicate dishes. Forty-eight hours following transfection, cells were treated either with 25 µM HMBME or solvent control. Both floating and adherent cells were collected after 2 hours of treatment and assessed for cell viability by trypan blue exclusion assay. The data shown here are average ± SD of three independent experiments. (B) Overexpression of constitutively active Akt protects LNCaP cells from undergoing apoptosis following treatment with HMBME. Experiments were conducted essentially as described in (A). Both floating and adherent cells were collected after 2 hours of treatment and assessed for apoptosis as described in Materials and Methods section. The data shown here are average ± SD of two independent transfections. (C) Influence of HMBME on transcriptional activity of the NFκB promoter. Transient transfections were performed with pNFκB reporter plasmid (1 µg/well) and pRL-TK plasmid (50 ng/well; renilla luciferase for normalization) as described in Materials and Methods section using Lipofectin reagent. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were treated with HMBME (25 µM) for 2 hours. Firefly and renilla luciferase activity was measured in the extracts prepared from these using Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega) in duplicate samples containing equal amounts of protein. Renilla luciferase activity was used to normalize for transfection efficiency. Results are expressed as the ratio of firefly luciferase/renilla luciferase at equal amounts of protein. The data shown here are a representative experiment that was performed for four times with two different preparations of plasmid. For cotransfection experiments, indicated expression plasmids (1 µg/well) were included along with the pNFκB reporter plasmid. The data shown here are a representative experiment that was performed for four times with two different preparations of plasmid. (D) EMSA of nuclear extracts prepared from control and HMBME-treated cells. Nuclear extract (5 µg) was incubated with approximately 0.2 ng of NFκB consensus oligonucleotide as radiolabeled probe as described in Materials and Methods section and the DNA-protein complexes were resolved on a 4% nondenaturing gel by electrophoresis and subject to autoradiography. (E) Identification of protein components of NFκB DNA-binding activity. Nuclear extracts prepared from LNCaP cells were preincubated with p65, p50, or NRS for 30 minutes on ice. These extracts were used in EMSA with NFkB probe as described in legends for (C). Supershifted complex is indicated as p65/p50 complex and NS indicates nonspecific band. (F) Western blot analysis of whole cell extracts from LNCaP cells following treatment with HMBME. Twenty-five micrograms of extract from control or HMBME-treated cells was fractionated on 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. After blocking, the membrane was incubated for 2 or 3 hours with the antibody p65. This was followed by incubation with secondary horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antirabbit IgG antibody (Sigma) in blocking solution. Bound antibody was detected by Supersignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate, following the manufacturer's directions (Pierce). The blot shown here is a representative blot of three independent experiments.

To show the involvement of Akt activation in HMBME-induced apoptosis, we measured apoptosis in LNCaP cells transfected with either pCMVMyrAkt or control vector (pCMV), as described in Materials and Methods section. Induction of apoptosis was assessed both by morphologic analyses as well as acridine orange/ethidium bromide staining. Microscopic observations of vector-transfected cells show characteristic features of apoptosis unlike MyrAkt-transfected cells following treatment with HMBME (data not shown). As shown in Figure 5B, between 20% and 25% of LNCaP cells transfected with control vector underwent apoptosis following HMBME treatment (after normalizing for spontaneous apoptosis). In contrast, overexpression of constitutively active Akt protected LNCaP cells from undergoing apoptosis following treatment with HMBME. These data demonstrate that HMBME-induced apoptosis is mediated through inhibition of Akt activation.

HMBME Reduces NFκB Transcriptional Activity, DNA-Binding Activity, and Levels of p65

NFκB is an important transcription factor that controls transcription of a large number of genes involved in various cell functions including apoptosis. Mammalian cells contain different subunits of NFκB including p65 (65-kDa DNA-binding subunit and an associated 50-kDa protein referred to as p50 [48]). We examined the role of NFκB in mediating HMBME-induced apoptosis using transient transfection expression assays using NFκB luciferase reporter vector containing four tandem copies of NFκB consensus sequence (Clontech Laboratories, Palo Alto, CA) and NFκB B DNA-binding activity in nuclear extracts prepared from cells treated with HMBME. As shown in Figure 5C, treatment with HMBME (25 µM for 2 hours) reduced the transcriptional activity of the NFκB promoter by about 50%. Under similar experimental conditions, HMBME did not affect the promoter activity of the vector alone. In addition, cotransfections performed with mutant IκBα super repressor (containing mutated serine residues at 32 and 36) blocked this activation of NFκB promoter activity that is consistent with previous reports (data not shown and Ref. [50]). These data indicate that NFκB/IκBα signaling has a role in mediating HMBME-mediated reduction in the transcriptional activity of NFκB in LNCaP cells.

We tested the ability of nuclear extracts prepared from LNCaP cells treated with HMBME to bind the NFκB oligonucleotide in EMSA. As shown in the Figure 5D, extracts prepared from untreated cells showed one major complex. This complex was abolished with an excess (100-fold molar) of unlabeled consensus NFκB but not with Sp1 oligonucleotide indicating the specificity of the interaction (data not shown). Extracts prepared from HMBME-treated cells showed a time-dependent decrease in the NFκB DNAbinding activity that was totally abolished by 24 hours. This correlates with the observed decrease in the transcriptional activity of the NFκB promoter following HMBME treatment (Figure 5C).

We wanted to establish the identity of the proteins in the observed DNA-protein complex formed with NFκB oligonucleotide in this experiment. Nuclear extracts prepared from LNCaP cells were preincubated with p65 or p50 antibodies and then analyzed by EMSA. As shown in Figure 5E, the bound complex was clearly supershifted in the presence of p65 antibody and partially supershifted in the presence of p50 antibody. This shows that the bound complex consists of both p65 and p50. Preincubation of the nuclear extracts with NRS had no effect on the DNA-protein interaction. We have also performed Western blot analysis using p65 in the extracts prepared from LNCaP cells treated with HMBME for different time points (30 minutes, 60 minutes, 2 hours, and 24 hours). As shown in Figure 5F, the levels of p65 showed timedependent decrease with exposure to HMBME. These blots were stripped and reprobed with β-actin to ensure equal loading of protein (data not shown). These results are consistent with the observed decrease in NFκB transcriptional activity and DNA-binding activity. These results showing the inhibition of NFκB signaling are consistent with published reports with curcumin, which is a parent compound for HMBME [51,52]. These data clearly indicate that interference with NFκB signaling pathway with HMBME could contribute to the observed antiproliferative activity with consequent induction of apoptosis.

NFκB usually resides in the cytoplasm in association with the inhibitory protein, IκB. Degradation of IκB in a proteosome-dependent signaling pathway leads to translocation of NFκB to the nucleus with subsequent activation of NFκB-dependent signaling pathway. Degradation of IκB occurs following its phosphorylation on two serine residues and subsequent ubiquitination. Although the IκB kinase (IKK) complex consisting of IKKα, IKKβ, and other regulatory proteins has been shown to mediate the phosphorylation of IκB, phosphorylation and activation of IKK by Akt also promote IκB degradation, allowing NFκB to activate the transcription of antiapoptotic genes [45,46]. Such activation of NFκB by Akt would be expected to decrease the likelihood of cell death. The data presented above illustrate that HMBME may induce apoptosis in LNCaP cells through inhibition of NFκB activity. Even when NFκB activity is blocked, other signaling pathways that act independent of NFκB may be active and block apoptosis. For example, as discussed above, Akt can inhibit apoptosis through phosphorylation of proapoptotic proteins such as BAD and other proteins. Hence, inhibition of activation of both Akt and NFκB by a single agent such as HMBME will have dual advantage.

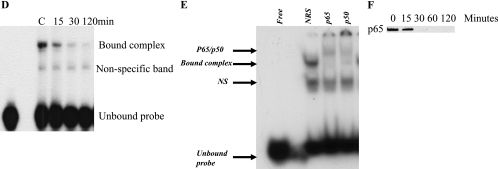

To investigate the role of Akt in mediating HMBME-induced apoptosis through NFκB, we measured the NFκB transcriptional activity in the presence and absence of constitutively active Akt. As shown in Figure 6A, overexpression of myristylated version of Akt (targeted to the plasma membrane and is constitutively active) in LNCaP cells, along with NFκB luciferase reporter, led to a fivefold increase in NFκB promoter activity over that obtained with empty vector. This indicates that Akt specifically influences NFκB induction. Subsequent experiments using an inactivating mutation of the kinase domain prevented Akt from potentiating NFκB-dependent transcription that is consistent with earlier reports [53]. However, HMBME treatment did not affect the Akt-mediated induction of NFκB transcriptional activity in LNCaP cells. This is also consistent with our data showing that overexpression of Akt protects cells from undergoing apoptosis (Figure 5B). We have also measured the ability of extracts prepared from these transfected cells to determine if Akt-mediated effects involve alterations in the NFκB DNA-binding activity. As shown in Figure 6B, extracts prepared from cells transfected with NFκB reporter plasmid showed DNA-binding activity that was reduced following treatment with HMBME (25 µM for 2 hours). This indicates that the observed reduction in the transcriptional activity (Figure 5C) is due to reduced DNA-binding activity. Extracts prepared from Akt-transfected cells showed a complex that is not altered following treatment with HMBME that is also consistent with the above transfection data. Although the over-expression of Akt activated NFκB promoter activity, we did not observe enhanced DNA-binding activity in extracts from Akt-transfected cells. Whereas it is most likely that Akt may not be influencing the NFκB activity through its DNA-binding activity, we do not rule out that the observed effect is due to low transfection efficiency.

Figure 6.

(A) Akt activates NFκB promoter activity. Cotransfection experiments were performed essentially as described above for Figure 5B with 1 µg/well of the indicated expression plasmids (pCMVMyrAkt, an activated form of Akt with the Src myristoylation signal fused in-frame to the c-Akt coding sequence; dn Akt, construct expressing inactive Akt due to mutation in the kinase domain; or control vector, pCDNA-3, along with the pNFκB reporter plasmid). Luciferase activity was determined as described above for Figure 5C. (B) EMSA using transfected extracts. Cell extracts prepared from the transfected cells were used in gel shift experiments as described in Figure 5D. “C” indicates control extract and “T” indicates treated extract (25 µM HMBME for 2 hours). “F” denotes free probe line without the protein extract. (C) Akt kinase activity and levels of p-Akt following treatment with HMBME. Actively growing LNCaP cells were treated with HMBME (25 µM) for 24 hours or for different time points as described in Materials and Methods section. Endogenous Akt was immunoprecipitated using an Akt monoclonal antibody. Following extensive washes, kinase reaction was performed in the presence of 200 µM cold ATP and GSK-3 substrate. Phosphorylation of GSK-3 was measured by Western blotting using an antiphospho-GSK-3 antibody. Western blotting using pAkt was performed essentially as described in legends for Figure 5F.

The possibility that HMBME interferes with the Akt kinase activity to affect Akt/NFκB cell survival signaling pathway was investigated. As shown in Figure 6C (panel A), the extracts prepared from untreated LNCaP cells showed Akt kinase activity. However, treatment with HMBME (25 µM) led to undetectable levels of Akt kinase activity. These data indicate that higher levels of Akt kinase activity in LNCaP cells may protect cells from undergoing apoptosis. Inhibition of Akt kinase activity by HMBME activates the apoptotic process. It is noteworthy to mention that Akt has been shown to phosphorylate IKK-α at threonine residue 23 [45]. Taken together, these results show that Akt augmentation of NFκB activity requires Akt kinase activity. The data illustrating the protection from HMBME-induced apoptosis through overexpression of constitutively active Akt further suggest that increased kinase activity is effective in blocking HMBMEinduced apoptosis. Extracts prepared from untreated LNCaP cells showed higher levels of p-Akt that is consistent with published reports (Figure 6C, panel B) [41–44]. However, treatment with HMBME (25 µM) showed a reduction in the levels of p-Akt that was completely abolished by 2 hours of incubation. These data clearly indicate that inhibition of Akt kinase activation may be the underlying mechanism responsible for the apoptotic effects of HMBME, although we have not established a functional link among HMBME-induced decrease in Akt kinase activity, NFκB activity, and increase in apoptosis. Our data suggest that it may be possible that inhibition of Akt kinase activity by HMBME activates the apoptotic process through inactivation of NFκB signaling. Such functional studies are in progress to determine the cause-and-effect relationship between Akt and NFκB during HMBME-induced apoptosis. It has been shown that the Cox-2 inhibitor, celecoxib, inhibits the growth of PCA cells through induction of apoptosis via a mechanism involving Akt signaling [54]. Although HMBME inhibited the growth of both androgen-responsive and androgen-independent cells that differ in the status of PTEN, it is not known if a similar mechanism as reported for LNCaP cells also operates in androgen-independent cells. Such studies are currently in progress in our laboratory.

Conclusions

Epidemiologic studies show marked geographic differences in the incidence of PCA, with men from Asian cultures having a lower occurrence of PCA than men from western countries. The apparent protection against PCA in Asian males may be due to various genetic and environmental factors because offspring from men who have moved from Asian to western countries experience an increased incidence of this disease similar to that of their new locales. Although PCA is initially dependent on androgens for growth and is thus responsive to androgen ablation, progression to androgen-insensitive state generally ensues. When this occurs, the progression is poor because no systemic therapy is effective. Therefore, there is an urgent need for targeted nonhormonal treatment that inhibits prostatic cancer cells.

Signaling pathways activated by growth factor receptors play an important role in the development of a neoplastic phenotype. As such, they represent excellent targets for novel antineoplastic drug development. The Akt pathway can be activated by various growth factors and plays a very important role in promoting growth and blocking apoptosis in various cancer models including PCA. Activated Akt can suppress apoptosis by mediating the phosphorylation of downstream effectors such as Bad and procaspase-9, indirectly through regulation of transcription factors such as NFκB. Thus, it may be a potentially more effective strategy to block a critical signal transduction pathway such as Akt that is common to multiple downstream events. The data presented in this report suggest that targeting Akt/NFκB signaling is a potential new strategy for suppression of cancer cell survival as a means of cancer management. The advantage of HMBME is several fold: 1) because of its smaller size, that nevertheless retains essential chemical functionality, HMBME can be expected to have a more favorable solubility than curcumin while still retaining curcumin's favorable biologic activities; and 2) lack of dieneone functions in HMBME will prevent it from undergoing rapid reductive metabolism as observed with curcumin, increasing its bioavailability. Much preclinical work would needs to be done before concluding the HMBME should move forward into clinical trials for PCA; however, we believe that if efficacy can be validated in several rodent models, it will be found that HMBME is well tolerated with little systemic toxicity.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge receiving various Akt expression plasmids used in this study from Arthur Weiss (Howard Hughes Medical Institute, University of California, San Francisco, CA) and IκBα (S32/S36) mutant from Z.-G. Liu (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). We also thank Norman Greenberg (Baylor College of Medicine) for providing the TRAMP cell lines. We also acknowledge the University of Colorado Comprehensive Cancer Center Flow Cytometry Core facility for assistance with flow cytometric analysis. We thank Angeeneh Adamian, Lynn Marie Mihalco, and Christina Mainar for technical help. Supported by a subcontract to APK from NCI CA 46934-15S1.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society, author. Cancer Facts and Figures. 2002 ( http://www.cancer.org)

- 2.Garnick MB. Prostate cancer: screening, diagnosis, and management. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118:804–818. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-10-199305150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huggins C, Hodges CV. Studies on prostate cancer: I.The effect of estrogen and of androgen injection on serum phosphatase in metastatic prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 1941;1:293–297. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scher HI, Steineck G, Kelly WK. Hormone refractory (D3) prostate cancer: refining the concept. Urology. 1995;46:142–148. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(99)80182-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pratt DE. Antioxidants and cancer prevention. In: M-T Huang, C-T Ho, CY Lee., editors. Phenolic Compounds in Food and their Effect on Health II ACS Symposium Series 507. Washington, DC: American Chemical Society; 1992. pp. 54–71. (Chapter 5) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ho C-T. Antioxidants and cancer prevention. In: M-T Huang, C-T Ho, CY Lee., editors. Phenolic Compounds in Food and Their Effect on Health II ACS Symposium Series 507. Washington, DC: American Chemical Society; 1992. pp. 2–7. (Chapter 1) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang M-T, Lysz T, Ferraro T, Abidi TF, Laskin JD, Conney AH. Inhibitory effects of curcumin on in vitro lipoxygenase and cyclooxygenase activities in mouse epidermis. Cancer Res. 1991;51:813–819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rao CV, Rivenson A, Simi B, Reddy B. Chemoprevention of colon carcinogenesis by dietary curcumin, a naturally occurring plant phenolic compound. Cancer Res. 1995;55:259–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Inano H, Onoda M, Inafuku N, Kubota M, Kamada Y, Osawa T, Kobayashi H, Wakabayashi K. Chemoprevention by curcumin during the promotion stage of tumorigenesis of mammary gland in rats irradiated with gamma-rays. Carcinogenesis. 1999;20:1011–1018. doi: 10.1093/carcin/20.6.1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deshpande SS, Ingle AD, Maru GB. Chemopreventive efficacy of curcumin-free aqueous turmeric extract in 7, 12-dimethylbenz(a)nthracene-induced rat mammary tumorigenesis. Cancer Lett. 1998;123:35–40. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(97)00400-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conney AH, Lou YR, Xie JG, Osawa T, Newmark HL, Liu Y, Chang RL, Huang MT. Some perspectives on dietary inhibition of carcinogenesis: studies with curcumin and tea. Prco Soc Exp Biol Med. 1997;216:234–245. doi: 10.3181/00379727-216-44173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin JK, Chen YC, Huang YT, Lin-Shiau SY. Suppression of protein kinase C and nuclear oncogene expression as possible molecular mechanisms of cancer chemoprevention by apigenin and curcumin. J Cell Biochem Suppl. 1997;28:39–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hanif R, Qiao L, Shiff SJ, Rigas B. Curcumin, a natural plant phenolic food additive, inhibits cell proliferation and induces cell cycle changes in colon adenocarcinoma cell lines by a prostaglandinindependent pathway. J Lab Clin Med. 1997;130:576–584. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2143(97)90107-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ikezaki S, Nishikawa A, Furukawa F, Kudo K, Nakamura H, Tamura K, Mori H. Chemopreventive effects of Curcumin on glandular stomach carcinogenesis induced by N-methyl-N-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine and sodium chloride in Rats. Anticancer Res. 2001;21:3407–3412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang M-T, Lysz T, Ferraro T, Abidi TF, Laskin JD, Conney AH. Inhibitory effects of curcumin on in vitro lipoxygenase and cyclooxygenase activities in mouse epidermis. Cancer Res. 1991;51:813–819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sambaiah K, Srinivasan K. Influence of spices and spice principles on hepatic mixed function oxygenase system in rats. Indian J Biochem Biophys. 1989;26:254–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perkins S, Verschoyle RD, Hill K, Parveen I, Threadgill MD, Sharma RA, Williams ML, Steward WP, Gescher AJ. Chemopreventive efficacy and pharmacokinetics of Curcumin in the Min-/+ mouse, a model of familial adenomatous polyposis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2002;11:535–540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dorai T, Gehani N, Katz A. Therapeutic potential of curcumin in human prostate cancer: I.Curcumin induces apoptosis in both androgen-dependent and androgen-independent prostate cancer cells. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2000;3:84–93. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dorai T, Cao Yi-C, Dorai B, Buttyan R, Katz AE. Therapeutic potential of curcumin in human prostate cancer: III. Curcumin inhibits proliferation, induces apoptosis, and inhibits angiogenesis of LNCaP prostate cancer cells in vivo. Prostate. 2001;47:293–303. doi: 10.1002/pros.1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Imaida K, Tamano S, Kato K, Ikeda Y, Asamoto M, Takahashi S, Nir Z, Murakoshi M, Nishino H, Shirai T. Lack of chemopreventive effects of lycopene and curcumin on epidermal rat prostate carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2001;22:467–472. doi: 10.1093/carcin/22.3.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ireson CR, Jones DJL, Orr S, Coughtrie MWH, Boocock DJ, Williams ML, Farmer PB, Steward WP, Gescher AJ. Metabolism of the cancer chemopreventive agent Curcumin in human and rat intestine. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2002;11:105–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pan MH, Huang TM, Lin JK. Biotransformation of curcumin through reduction and glucuronidation in mice. Drug Metab Dispos. 1999;27:486–494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheng AL, Lin JK, Hsu MM, Shen TS, Ko JY, Lin JT, Wu MS, Yu HS, Jee SH, Chen GS, Chen TM, Chen CA, Lai MK, Pu YS, Pan MH, Wang UJ, Tsai CC, Hsieh CY. Phase I chemoprevention clinical trial of curcumin. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 1998;17:558A. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharma RA, Hill KA, McLelland HR, Ireson CR, Euden SA, Manson MM, Pirmohamed M, Marnett LJ, Gescher AJ, Steward WP. Pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetics study of oral curcumin extract in patients with colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:1834–1900. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ireson CR, Orr S, Jones DJL, Verschoyle R, Lim CK, Luo JL, Howells L, Plummer SM, Jukes R, Williams M, Steward WP, Gescher A. Characterization of metabolites of the chemopreventive agent curcumin in humans and rat hepatocytes and rat plasma and evaluation of their ability to inhibit phorbol ester-induced prostaglandin E2 production. Cancer Res. 2001;61:1058–1064. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar AP, Rajnarayanan R, Garcia GE, Adamian A, Alworth WL, Slaga TJ. Novel curcumin derivatives induces apoptosis through Akt-NFκB signaling in human prostate cancer cells. Proc Am Cancer Soc. 2002;43:66. (Supplement; Abstract LB-77) [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumar AP, Garcia GE, Slaga TJ. 2-Methoxyestradiol blocks cell cycle progression at G2/M phase and inhibits growth of human prostate cancer cells. Mol Carcinog. 2001;31:111–124. doi: 10.1002/mc.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hayward S, Wang Y, Cao M, Hom YK, Zhang B, Grossfeld GD, Sudilovsky D, Cunha GR. Malignant transformation in a nontumorigenic human prostatic epithelial cell line. Cancer Res. 2001;61:8135–8142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Foster BA, Gingrich JR, Kwon ED, Madias C, Greenberg NM. Characterization of prostatic epithelial cell lines derived from transgenic adenocarcinoma of the mouse prostate (TRAMP) model. Cancer Res. 1997;57:3325–3330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McGahon AJ, Martin SJ, Bissonnette RP, Mahboubi A, Shi Y, Mogil RJ, Nishioka WK, Green DR. The end of the (cell) line: methods for the study of apoptosis in vitro. Methods Cell Biol. 1995;46:153–185. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)61929-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kumar AP, Garcia GE, Orsborn J, Levin VA, Slaga TJ. 2-Methoxyestradiol interferes with NFκB transcriptional activity in primitive neuroectodermal brain tumors: implications for management. Carcinogenesis. 2003;24:209–216. doi: 10.1093/carcin/24.2.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kumar AP, Mar PK, Zhao B, Montgomery RL, Kang D-C, Butler AP. Regulation of rat ornithine decarboxylase promoter activity by binding of transcription factor Sp1. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:4341–4348. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.9.4341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kumar AP, Butler AP. Transcription factor Sp3 antagonizes activation of the ornithine decarboxylase promoter by Sp1. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:2012–2019. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.10.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rayet B, Gelinas C. Aberrant rel/nfkb genes and activity in human cancer. Oncogene. 1999;18:6938–6947. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baldwin AS., Jr Control of oncogenesis and cancer therapy resistance by the transcription factor NF-kappaB. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:241–246. doi: 10.1172/JCI11991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kandel ES, Hay N. The regulation and activities of the multifunctional serine/threonine kinase AKT/PKB. Exp Cell Res. 1999;253:210–229. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burgering BMT, Coffer P. Protein kinase B (c-Akt) in phosphatidylinositol 3-OH kinase signal transduction. Nature. 1995;376:599–602. doi: 10.1038/376599a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Datta SR, Brunet A, Greenberg ME. Cellular survival: a play in three Akts. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2905–2927. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.22.2905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Toker A. Protein kinases as mediators of phosphoinositide 3-kinase signaling. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;57:652–658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vivanco I, Sawyers CL. The phosphotidylinositol 3-kinase-AKT pathway in human cancer. Nat Rev/Cancer. 2002;2:489–501. doi: 10.1038/nrc839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Malik SN, Brattain M, Ghosh PM, Troyer DA, Prihoda T, Bedolla R, Kreisberg JI. Immunohistochemical demonstration of phospho-Akt in high Gleason grade prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:1168–1171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McMenamin ME, Soung P, Perera S, Kaplan I, Loda M, Sellers R. Loss of PTEN expression in paraffin-embedded primary prostate cancer correlates with high Gleason score and advanced stage. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4291–4296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Persad S, Attwell S, Gray V, Delcommenne M, Troussard A, Sanghera J, Dedhar S. Inhibition of integrin-linked kinase (ILK) suppresses activation of protein kinase B/Akt and induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis of PTEN mutant prostate cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:3207–3212. doi: 10.1073/pnas.060579697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Teng DH, Hu R, Lin H, Davis T, Iliev D, Frye C, Swedlund B, Hansen KL, Vinson VL, Gumpper KL, et al. MMAC1/PTEN mutations in primary tumor specimens and tumor cell lines. Cancer Res. 1997;57:5221–5225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ozes ON, Mayo LD, Guston JA, Pfeffer SR, Pfeffer LM, Donner DB. NFkB activation by tumor necrosis factor requires the Akt serine-threonine kinase. Nature. 1999;401:82–85. doi: 10.1038/43466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Romashkova JA, Makarov SS. NFκB is a target of Akt in antiapoptotic PDGF signaling. Nature. 1999;401:86–89. doi: 10.1038/43474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Beg AA, Sha WC, Bronson RT, Ghosh S, Baltimore D. Embryonic lethality and liver degeneration in mice lacking the RelA component of NFκB. Nature. 1995;376:167–170. doi: 10.1038/376167a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ghosh S, Karin M. Missing pieces in the NFkB puzzle. Cell. 2002;109:S81–S96. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00703-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Suh J, Paynandi F, Edelstein LC, Amenta PS, Zong W-X, Gelinas C, Rabson AB. Mechanisms of constitutive NFκB activation in human prostate cancer cells. Prostate. 2002;52:183–200. doi: 10.1002/pros.10082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu Z-G, Hsu H, Goeddel DV, Karin M. Dissection of TNF receptor I effector functions: JNK activation is not linked to apoptosis while NFκB activation prevents cells death. Cell. 1996;87:565–576. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81375-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Singh S, Aggarwal BB. Activation of transcription factor NFκB is suppressed by curcumin (diferuloylmethane) J Biol Chem. 1995;270:24995–25000. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.42.24995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mukhopadhyay A, Bueso-Ramos C, Chatterjee D, Pantazis P, Aggarwal BB. Curcumin down regulates cell survival mechanism in human prostate cancer cell lines. Oncogene. 2001;20:7597–7609. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kane LP, Shapiro VS, Stokoe D, Weiss A. Induction of NFκB by the Akt/PKB kinase. Curr Biol. 1999;9:601–604. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80265-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hsu AL, Ching TT, Wang DS, Song X, Rangnekar VM, Chen CS. The cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor celecoxib induces apoptosis by blocking Akt activation in human prostate cancer cells independently of Bcl-2. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:11397–11403. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.15.11397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]