Abstract

Twelve zeolitic imidazolate frameworks (ZIFs; termed ZIF-1 to -12) have been synthesized as crystals by copolymerization of either Zn(II) (ZIF-1 to -4, -6 to -8, and -10 to -11) or Co(II) (ZIF-9 and -12) with imidazolate-type links. The ZIF crystal structures are based on the nets of seven distinct aluminosilicate zeolites: tetrahedral Si(Al) and the bridging O are replaced with transition metal ion and imidazolate link, respectively. In addition, one example of mixed-coordination imidazolate of Zn(II) and In(III) (ZIF-5) based on the garnet net is reported. Study of the gas adsorption and thermal and chemical stability of two prototypical members, ZIF-8 and -11, demonstrated their permanent porosity (Langmuir surface area = 1,810 m2/g), high thermal stability (up to 550°C), and remarkable chemical resistance to boiling alkaline water and organic solvents.

Keywords: catalysis, hydrogen storage, metal–organic frameworks, porosity, zeolites

A large segment of the global economy ($350 billion) is based on the use of crystalline microporous zeolites in petrochemical cracking, ion-exchange for water softening and purification, and in the separation of gases (1). Zeolite structures are composed of tetrahedral Si(Al)O4 units covalently joined by bridging O atoms to produce >150 different types of framework (2). A long-standing challenge is to incorporate transition metal ions and organic units within their pores and, more desirably, to do so as an integral part of the zeolite framework. This ability would be useful in many catalytic applications because the pores would be lined with a high concentration of ordered transition metal sites whose electronic and steric properties can be tailored by functionalization of the organic links. However, the vision of achieving such a zeolite that combines these features remains largely unrealized. Here, we outline a general synthesis of structures having zeolite framework topologies in which all tetrahedral atoms are transition metals, and all bridging ones are imidazolate (IM) units.

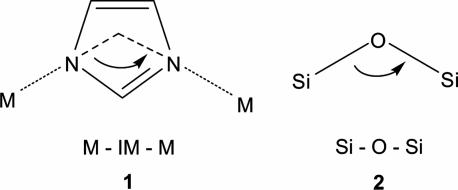

Imidazole can lose a proton to form IM, 1. In examining the dense-phases Co(IM)2 and Zn(IM)2, whose structures are based on nets of linked CoN4 or ZnN4 tetrahedra (3, 4), we noticed that IM bridges make an M–IM–M angle, 1, close to 145°, which is coincident with the Si–O–Si angle, 2, which is preferred and commonly found in many zeolites (see Scheme 1). We believed that it should be possible under the right conditions to prepare metal IMs adopting open-framework zeolite structures. Indeed, a number of relatively new Fe(II) (5), Co(II) (6, 7), Cu(II) (8), and Zn(II) (9) IM compounds have structures that are based on zeolite-like tetrahedral nets. However, these materials are relatively dense (nonporous) and/or low-symmetry structures. Only very recently, Zn(II) IMs having symmetrical porous structures analogous to zeolites were reported (10). Two of the aforementioned compounds are included, as zeolitic IM framework (ZIF)-7 and -8, among the library of ZIFs we report here (Fig. 1).** The focus of this work is to report a general strategy that has led to previously undescribed ZIF structures based on other zeolite nets. More significantly, we confirm the porosity of ZIFs and find that unlike other metal–organic compounds, ZIFs have exceptional chemical stability in refluxing organic solvents, water, and aqueous alkaline solution, a finding that has not been described previously. These results point to the potential applications and rich structural diversity of this as-yet-undeveloped class of porous materials.

Scheme 1.

The bridging angles in metal IMs (1) and zeolites (2).

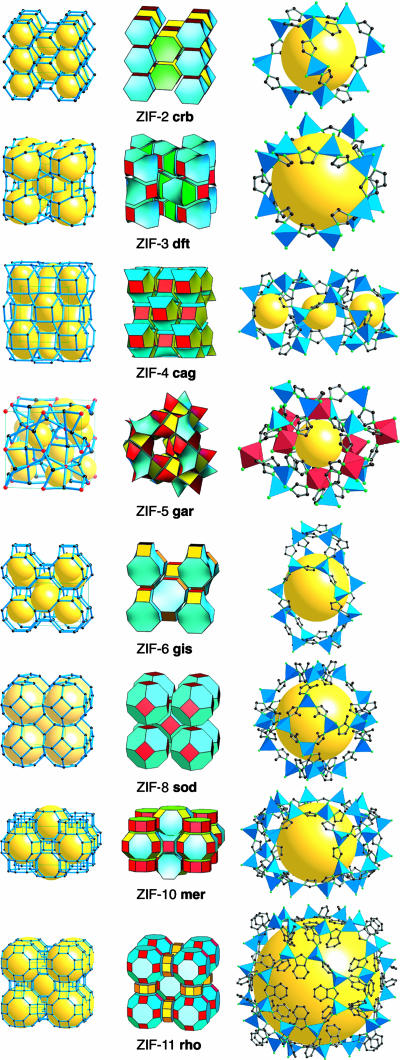

Fig. 1.

The single crystal x-ray structures of ZIFs. (Left and Center) In each row, the net is shown as a stick diagram (Left) and as a tiling (Center). (Right) The largest cage in each ZIF is shown with ZnN4 tetrahedra in blue, and, for ZIF-5, InN6 octahedra in red. H atoms are omitted for clarity.

Results and Discussion

General Synthetic Strategy for and Structural Diversity of ZIFs.

All ZIFs were synthesized by using solvothermal methods (see Materials and Methods). Highly crystalline materials were obtained by combining the requisite hydrated metal salt (usually nitrate) and imidazole-type linker in an amide solvent such as N,N-diethylformamide (DEF). The resulting solutions were heated (85–150°C) wherefrom ZIFs precipitated after 48–96 h and were readily isolated. Single crystals suitable for x-ray structure analysis were selected from the ZIF precipitate, and those structures are illustrated in Fig. 1. For each structure, the metal center is solely coordinated by the N atoms of IM to give overall neutral frameworks. The five-membered IM ring serves as the bridging unit between the Zn(II), Co(II), or In(III) centers and imparts angle 1 of ≈145° throughout the frameworks via coordinating N atoms in the 1,3-positions of the ring. The organic components of ZIFs provide for organically lined cages and channels rather than a silicate oxide surface as in zeolites. Some ZIFs are obtained by using IM linkers with phenyl [benzimidazolate (PhIM)] or methyl [2-methylimidazolate (MeIM)] groups, which also project into the pore regions. The presence of these groups lowers in some cases the crystallographic space group symmetry of the ZIF compared with its zeolite counterpart; however, the net defined by joining the metal atom nodes corresponds exactly.

We note that our concept (11) of a default structure (a naturally preferred high-symmetry topology most often adopted by a solid-state material) does not apply directly either to silicates or IMs. Angle 2 of 145° makes it impossible for the highest symmetry 4-coordinated structure of Fd 3m diamond to form; therefore, lower symmetries are invariably found for silicas. Nature prefers P3121 quartz over the P41212 cristobalite polymorph, but by only 1 or 2 kJ/mol, and >10 forms of silica are known to be of essentially equal energy (on the scale of bond energies). To reproducibly prepare these and related structures, one needs a structure-directing agent, and this agent is of course the key to zeolite synthesis. Indeed, the present work shows that structure-directing agents (amide solvent media and linker functionalization) along with control of reaction conditions are equally effective in achieving a wide variety of ZIF structures. To illustrate the potential for synthetic diversity, we call attention to the fact that the zeolite topologies DFT, GIS, and MER (Table 1) resulting from our synthesis have not been reported previously for any kind of metal–organic frameworks (MOFs), and more importantly, all of the seven distinct zeolitic nets that the ZIFs adopt are uninodal (one topological kind of vertex): only 15% of known zeolite nets are uninodal. Furthermore, we demonstrate that ZIFs are not restricted to purely tetrahedral nets. The first example of an IM based on a mixed-coordination net, In2Zn3(IM)12 with In(III) in octahedral coordination environment, is also reported. This structure has the topology of the Al2Si3O12 part of a garnet, such as grossularite Ca3Al2Si3O12. The synthesis of this structure hints at the extraordinarily rich chemistry awaiting systematic exploration of IMs.

Table 1.

Composition, structure, and net parameters of ZIF series of compounds

| ZIF-n | Composition | Net* | Zeolite† | T/V,‡ nm−3 | d,§ Å | N¶ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZIF-1 | Zn(IM)2 | crb | BCT | 3.64 | 6.94 | 12 |

| ZIF-2 | Zn(IM)2 | crb | BCT | 2.80 | 6.00 | 12 |

| ZIF-3 | Zn(IM)2 | dft | DFT | 2.66 | 8.02 | 16 |

| ZIF-4 | Zn(IM)2 | cag | — | 3.68 | 2.04 | 20 |

| ZIF-5 | In2Zn3(IM)12 | gar | — | 3.80 | 3.03 | 20 |

| ZIF-6 | Zn(IM)2 | gls | GIS | 2.31 | 8.80 | 20 |

| ZIF-7 | Zn(PhIM)2 | sod | SOD | 2.50 | 4.31 | 24 |

| ZIF-8 | Zn(MeIM)2 | sod | SOD | 2.47 | 11.60 | 24 |

| ZIF-9 | Co(PhIM)2 | sod | SOD | 2.51 | 4.31 | 24 |

| ZIF-10 | Zn(IM)2 | mer | MER | 2.25 | 12.12 | 24 |

| ZIF-11 | Zn(PhIM)2 | rho | RHO | 2.01 | 14.64 | 48 |

| ZIF-12 | Co(PhIM)2 | rho | RHO | 2.01 | 14.64 | 48 |

*For definitions of three-letter abbreviations, see Reticular Chemistry Structure Resource (http://okeeffe-ws1.la.asu.edu/RCSR/home.htm).

†See ref. 2.

‡T/V is the density of metal atoms per unit volume.

§d is the diameter of the largest sphere that will fit into the framework.

¶N is the number of vertices of the largest cage.

Table 1 summarizes topology, density, and pore size data for ZIFs. The nets of the structures are denoted by a boldface three-letter symbol (for symbol definitions, see the Reticular Chemistry Structure Resource, available at http://okeeffe-ws1.la.asu.edu/RCSR/home.htm) that is often the same as that of the corresponding zeolite net (2). We also give the density of ZIFs by using the traditional zeolite measure of number of tetrahedral vertices per unit volume (T/V). In an IM framework containing, for example, Zn(II), the Zn···Zn distance is ≈6.0 Å, whereas the corresponding Si···Si distance in a silicate is ≈3.0 Å; accordingly, the density (T/V) of an IM analog (i.e., ZIF) of a silicate zeolite is eight times less. For the structures reported here, T/V is in the range 2.0–3.7 nm−3 (Table 1). For comparison, the density for oxide zeolites is 12–20 nm−3, and for the lowest-density known oxide framework (12) it is 7.1 nm−3. We also list the size of the largest sphere that will fit into the cavities without contacting the van der Waals internal surface of the framework. In every case, the atom nearest to the center of the cavity is H, and we have used a van der Waals radius of 1.2 Å for H in determining the fitting sphere size. Note that this value is an approximate indicator of the cage volume because in some cases the cages are elliptical. The table also gives the number of vertices of the largest cage in each structure; this value ranges from 12 (crb) to 48 (rho).

In Fig. 1, we illustrate the eight nets of the ZIF structures in three ways. First, we show them as stick diagrams of the nets; next, we show the same structures decomposed into tiles (generalized polyhedra or cages that combine to completely fill space). For some structures (i.e., cag, gis, and sod) there is just one kind of tile. Finally, the largest cage in the real structure of representative IMs is shown on the right. Replacement of Zn(II) by Co(II) makes essentially no metrical difference to the structure; thus, ZIF-7 and -11 are virtually identical to ZIF-9 and -12, respectively.

Porosity and Stability of ZIFs.

To examine the architectural, thermal, and chemical stability and porosity of ZIFs, we focused on two prototypical structures, namely ZIF-8 and -11. They were prepared at the gram scale to allow detailed investigation of the aforementioned properties. An important structural feature of these two ZIFs is that they possess large pores (11.6 and 14.6 Å in diameter for ZIF-8 and -11, respectively) connected through small apertures (3.4 and 3.0 Å across for ZIF-8 and -11, respectively). The pore sizes are approximately twice as large as those of their zeolite counterparts by virtue of the longer IM linking units (see above); however, the existence of side chain or ring on the link renders the aperture sizes to the lower limit for molecular sieves (Table 2).

Table 2.

Structural characteristics of ZIF-8 and -11 calculated from single crystal x-ray analysis

| ZIF-n | Pore aperture diameter, Å |

Pore diameter, Å | Surface area, m2/g | Pore volume, cm3/g | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8-ring | 6-ring | 4-ring | ||||

| ZIF-8 | — | 3.4 | * | 11.6 | 1,947 | 0.663 |

| ZIF-11 | 3.0 | 3.0 | * | 14.6 | 1,676 | 0.582 |

All calculations were based on the Free Volume routine of cerius2 software (Version 4.2; MatSci; Accelrys, Inc., San Diego; probe radius 1.4 Å, medium grid) and on the single crystal x-ray structures of ZIF-8 and -11 with guests removed and disorder effects averaged.

*The aperture sizes of the 4-rings in both ZIF-8 and -11 are negligible.

Thermal gravimetric analysis (TGA) performed on as-synthesized ZIF-8 and -11 revealed these compounds’ remarkable thermal stability (see Section S5 in Supporting Appendix, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, for all data and interpretations regarding guest mobility and thermal stability of ZIF-8 and -11). The TGA trace for ZIF-8 showed a gradual weight-loss step of 28.3% (25–450°C), corresponding to partial loss of guest species [1 N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) and 3 H2O; calcd. 35.9%], followed by a plateau (450–550°C). More impressively, the TGA trace for ZIF-11 revealed a sharp weight-loss step of 22.8% (25–250°C), corresponding to the escape of all N,N-diethylformamide (DEF) solvent molecules trapped in the pores (0.9 DEF; calcd. 23.3%), despite the fact that DEF is actually much larger than the aperture of ZIF-11 in size. The TGA trace of ZIF-11 also showed a long plateau in the temperature range 250–550°C, indicating its high thermal stability in the absence of guest molecules. We note that the guests in ZIF-8 and -11 were released without damaging the frameworks, as evidenced by the coincidence of the powder x-ray diffraction (PXRD) patterns of a ZIF-8 sample and a ZIF-11 sample heated to and held at 500 and 300°C, respectively, in N2 atmosphere with the PXRD patterns simulated from single crystal structures. Such high thermal stability of ZIFs (up to 550°C in N2) is well beyond that of the permanently porous cubic structure of MOF-5 (decomposes at 450°C in N2), only matched by very few MOFs having relatively dense structures (13, 14).

The amide guests included in as-synthesized ZIF-8 and -11 could be more readily removed by solvent-exchange. The thermogravimetric behavior of ZIF-8 and -11 were significantly simplified after they were immersed in organic solvents, such as methanol. To remove the guest species from the frameworks and prepare the evacuated forms of ZIF-8 and -11 for gas-sorption analysis, the as-synthesized ZIF samples were immersed in methanol at ambient temperature for 48 h, and evacuated at ambient temperature for 5 h, then at an elevated temperature (300°C for ZIF-8; 180°C for ZIF-11) for 2 h. ZIF samples thus obtained were optimally evacuated, as evidenced by their well maintained PXRD patterns and the long plateau (25–550°C) in their TGA traces (see Section S5 in Supporting Appendix).

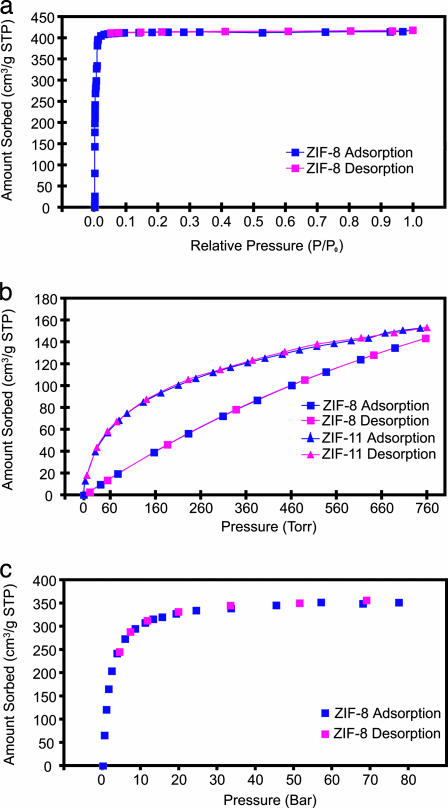

The architectural rigidity and consequently the permanent porosity of evacuated ZIF-8 and -11 were unequivocally proven by gas-sorption analysis. Type I nitrogen sorption isotherm behavior was observed for ZIF-8 (Fig. 2a), which reveals its microporous nature. Apparent surface areas of 1,810 m2/g (Langmuir model) and 1,630 m2/g [Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) model] for ZIF-8 were obtained by using the data points on the adsorption branch in the range of P/P0 = 0.01–0.10, and a micropore volume of 0.636 cm3/g for ZIF-8 was obtained based on a single data point at P/P0 = 0.10 (see Section S6 in Supporting Appendix for detailed gas-sorption analysis and data interpretation for ZIF-8).†† The experimental surface area and micropore volume values of ZIF-8 fit well with the predictions based on its single crystal structure (Table 2). These surface areas surpass the highest values reported for zeolites and ordered mesoporous silica-type materials (15–17). Conversely, ZIF-11 was nonporous to nitrogen because its aperture size (3.0 Å) was smaller than the kinetic diameter of nitrogen (3.6 Å) (15); however, it was able to take up hydrogen. Both ZIF-8 and -11 showed reversible hydrogen sorption behavior (Fig. 2b). Interestingly, the initial hydrogen uptake of ZIF-11 was much higher than that of ZIF-8, because of its unique cage interior, which is composed of protruding benzene side rings of the PhIM links around which favorable hydrogen sorption sites may be generated. However, ZIF-8 was similar to ZIF-11 in hydrogen uptake when the adsorbate pressure approached 1 atm [145 cm3/g at standard temperature and pressure (STP)] or 12.9 mg/g for ZIF-8; 154 cm3/g STP or 13.7 mg/g for ZIF-11). This result is expected because ZIF-8 has higher surface area and pore volume (Table 2). The ultimate hydrogen capacity of ZIF-8 was uncovered in a high-pressure (up to 80 bar) hydrogen sorption measurement at 77 K on a large batch of evacuated ZIF-8 (0.724 g), which showed 350 cm3/g STP (31 mg/g) at 55 bar. The hydrogen uptake of ZIF-8 and its Langmuir surface area (1,810 m2/g) fit well in a linear relationship proposed recently based on our high-pressure hydrogen sorption measurements on a series of MOFs with high surface areas (18).

Fig. 2.

The gas-sorption isotherms for prototypical ZIFs. (a) Nitrogen isotherm at 77 K for ZIF-8 sod. (b) Hydrogen isotherms at 77 K for ZIF-8 sod and ZIF-11 rho. (c) High-pressure hydrogen isotherm at 77 K for ZIF-8 sod.

Thus far, we have demonstrated that ZIFs are comparable with some of the very porous MOF compounds in surface area and pore volume, and they outperform traditional crystalline microporous materials such as zeolites and ordered mesoporous silicas. We believe this performance is due to the fully exposed edges and faces of the organic links; characteristics that have been proposed as key to creating exceptionally high surface areas (19).

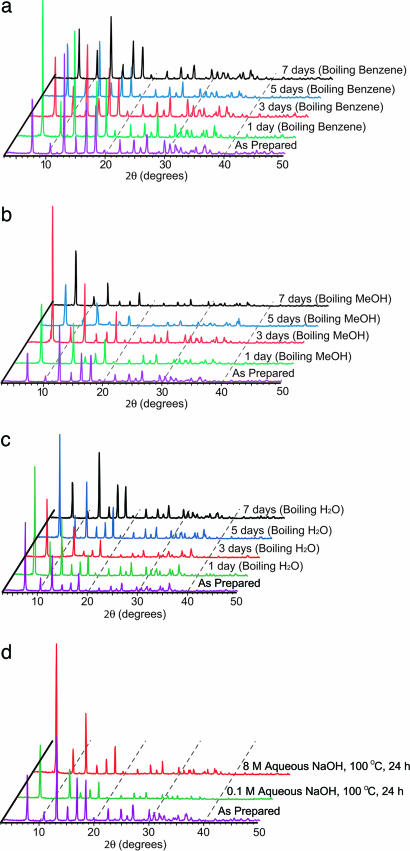

The chemical stability of ZIFs was examined by suspending samples of ZIF-8 and -11 in boiling benzene, methanol, water, and aqueous sodium hydroxide (Fig. 3), conditions that reflect extreme operational parameters of typical industrial chemical processes. ZIF samples were immersed in the desired solvent for 1–7 days at ambient temperature, 50°C, and at the boiling point of each medium. During this process, samples were periodically observed under an optical microscope and found to be insoluble under each of these conditions. PXRD patterns collected for each sample at designated intervals showed that the solid samples of ZIF-8 and -11 maintained their full crystallinity and were clearly impervious to the boiling organic solvents for 7 days. Both ZIFs sustained their structures in water at 50°C for 7 days. However, only ZIF-8 maintained its structure for 7 days in boiling water, whereas ZIF-11 was transformed to another crystalline material after 3 days (see Section S4 in Supporting Appendix). ZIF-8 thus was further probed and shown to be unchanged for up to 24 h in 0.1 and 8 M aqueous sodium hydroxide at 100°C. We note that the hydrothermal stability of ZIF-8 is superior to those of original MCM and SBA types of ordered mesoporous silica (17), even rivaling the ultrastable derivatives of these materials (20).

Fig. 3.

The PXRD patterns for ZIF-8 samples measured during chemical stability tests. (a) In refluxing benzene at 80°C for up to 7 days. (b) In refluxing methanol at 65°C for up to 7 days. (c) In refluxing water at 100°C for up to 7 days. (d) In refluxing aqueous NaOH solution for up to 1 day.

This exceptional resistance to hydrolysis is outstanding among metal–organic solids. Two plausible explanations can be advanced: first, the hydrophobic pore and surface structure of ZIFs likely repels water molecules preventing the attack of ZnN4 units and dissolution of the framework; and second, bonding between IM and Zn(II)/Co(II) is among the most stable for N-donor ligands (on the scale of metal-complex formation constants) (21). In combination, these two features of ZIFs impart hydrothermal stability more akin to covalent solids.

In this work, we have identified a general pathway to robust porous materials with exceptional chemical stability and great flexibility in varying their organic and inorganic components. We expect that this finding will lead to many new applications previously unrealized in oxide based porous materials.

Materials and Methods

Typical ZIF Synthesis.

(ZIF syntheses are exemplified here by the synthesis of ZIF-8; see Section S1 in Supporting Appendix for detailed synthetic procedures for all ZIFs.) A solid mixture of zinc nitrate tetrahydrate Zn(NO3)2·4H2O (0.210 g, 8.03 × 10−4 mol) and 2-methylimidazole (H-MeIM) (0.060 g, 7.31 × 10−4 mol) was dissolved in 18 ml of DMF in a 20-ml vial. The vial was capped and heated at a rate of 5°C/min to 140°C in a programmable oven and held at this temperature for 24 h, then cooled at a rate of 0.4°C/min to room temperature. After removal of mother liquor from the mixture, chloroform (20 ml) was added to the vial. Colorless polyhedral crystals were collected from the upper layer, washed with DMF (10 ml × 3), and dried in air for 10 min (yield: 0.032 g, 25% based on H-MeIM). The product was formulated by using elemental microanalysis as Zn(MeIM)2·(DMF)·(H2O)3 (C11H23N5O4Zn; Calcd. C, 37.25; H, 6.54; N, 19.74. Found. C, 37.69; H, 5.22; N, 19.58). The purity of ZIF-8 product has also been confirmed by PXRD analysis (see Section S3 in Supporting Appendix).

Single Crystal X-Ray Diffraction Studies.

All of the intensity data were collected on a SMART APEX CCD diffractometer (Bruker–AXS, Madison, WI) with graphite monochromated MoKα (λ = 0.71073 Å) radiation. Structures were solved by direct methods, and successive difference Fourier syntheses were made with the shelxtl software package (Bruker–AXS). See Supporting Appendix for full data-handling information and metrical data. Crystal data are as follows: ZIF-1 (crb, monoclinc form): monoclinic, space group P21/n; a = 9.740 (2), b = 15.266 (3), c = 14.936 (3) Å, β = 98.62 (3)°; V = 2195.8 (8) Å3, R1 = 0.0423. ZIF-2 (crb, orthorhombic form): orthorhombic, space group Pbca; a = 9.679 (3), b = c = 24.114 (6) Å; V = 5707 (3) Å3, R1 = 0.0591. ZIF-3 (dft): tetragonal, space group P42/mnm; a = b = 18.970 (2), c = 16.740 (3) Å; V = 6024.3 (1) Å3, R1 = 0.0610. ZIF-4 (cag): orthorhombic, space group Pbca; a = b = 15.395 (2), c = 18.426 (2) Å; V = 4342.2 (8) Å3, R1 = 0.0406. ZIF-5 (gar): cubic, space group Ia3d; ao = 21.9619 (6) Å; V = 10592.8 (5) Å3, R1 = 0.0191. ZIF-6 (gis): tetragonal, space group I41/amd; a = b = 18.515 (3), c = 20.245 (4) Å; V = 6940.2 (2) Å3, R1 = 0.0642. ZIF-7: [sod–Zn(II)–PhIM form]: hexagonal, space group R3; a = b = 22.989 (3), c = 15.763 (3) Å; V = 7214 (2) Å3, R1 = 0.0707. ZIF-8: [sod–Zn(II)–MeIM form]: cubic, space group I343m; ao = 16.9910 (1) Å; V = 4905.2 (6) Å3, R1 = 0.0314. ZIF-9 [sod–Co(II)–PhIM form]: hexagonal, space group R3; a = b = 22.9437 (2), c = 15.747 (2) Å; V = 7178.8 (1) Å3, R1 = 0.0979. ZIF-10 (mer): tetragonal, space group I4/mmm; a = b = 27.0608 (2), c = 19.406 (3) Å; V = 14211 (2) Å3, R1 = 0.0636. ZIF-11 [rho–Zn(II)–PhIM form]: cubic, space group Pm3m; ao = 28.7595 (1) Å; V = 23787.2 (2) Å3, R1 = 0.0787. ZIF-12 [rho–Co(II)–PhIM form]: cubic, space group Pm3m; ao = 28.7595 (1) Å; V = 23787.2 (2) Å3, R1 = 0.1064. Atomic coordinates are freely available for download from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre by citing deposition numbers 602535 (ZIF-1), 602536 (ZIF-2), 602537 (ZIF-3), 602538 (ZIF-4), 602539 (ZIF-5), 602540 (ZIF-6), 602541 (ZIF-7), 602542 (ZIF-8), 602543 (ZIF-9), 602544 (ZIF-10), 602545 (ZIF-11), 602546 (ZIF-12).

PXRD Studies.

Powder x-ray data were collected by using a D8-Advance θ-2θ diffractometer (Bruker) in reflectance Bragg–Brentano geometry employing Ni-filtered CuKα line focused radiation at 1,600 W (40 kV, 40 mA) power and equipped with a Na(Tl) scintillation detector fitted with a 0.2-mm radiation entrance slit. Samples were mounted on zero background sample holders by dropping powders from a wide-blade spatula and then leveling the sample surface with a razor blade. All samples were ground before PXRD experiment.

TGA.

All samples were run on a Q-500 series thermal gravimetric analyzer (TA Instruments, New Castle, DE) with samples held in platinum pans in a continuous-flow nitrogen atmosphere. Samples were heated at a constant rate of 5°C/min during all TGA experiments.

Gas-Sorption Measurements.

All low-pressure gas-sorption experiments (up to 1 atm) were performed on a Autosorb-1C automatic volumetric instrument (Quantachrome, Boynton Beach, FL). High-pressure hydrogen sorption experiments (up to 80 bar) were performed on a HPA-100 volumetric instrument (VTI, Hialeah, FL) equipped with a home-made liquid nitrogen cooling system to sustain a constant coolant bath level. The compressibility factors of high-pressure gases were determined by using the refprop program [Version 7.0; National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), Gaithersburg, MD] and the NIST Standard Reference Data Base 23 (see ref. 18 for details of high-pressure hydrogen sorption measurements). Before gas-sorption analysis, ZIF-8 and -11 samples were immersed in methanol at ambient temperature for 48 h and evacuated at ambient temperature for 5 h, then at an elevated temperature (300°C for ZIF-8, 180°C for ZIF-11) for 2 h.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Antek Wong-Foy for his invaluable comments. This work was supported by National Science Foundation Grant DMR-0242630. Hydrogen adsorption measurement was supported by Department of Energy Project DE-FG-3605GO15001. O.M.Y. was the principal investigator.

Abbreviations

- IM

imidazolate

- ZIF

zeolitic IM framework

- PhIM

benzimidazolate

- MeIM

2-methylimidazolate

- DMF

N,N-dimethylformamide

- MOF

metal–organic framework

- TGA

thermal gravimetric analysis

- PXRD

powder x-ray diffraction.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Data deposition: Atomic coordinates for all ZIFs (12 structures) have been deposited in the Cambridge Structural Database, Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, United Kingdom (CSD reference nos. 602535–602546).

The compounds having the same framework composition and structure as ZIF-7 and -8 were published in refs. 9 and 10, respectively. We note that we used a completely different and more efficient method to prepare these compounds. In particular, ZIF-8 was prepared solvothermally within 24 h, whereas the synthesis of the same structure reported in ref. 10 required a very long reaction time (1 month).

Since our work was completed, a Langmuir surface area of 1,400 m2/g was reported for a material having the same framework composition and structure as ZIF-8 (10).

References

- 1.Maesen T. L. M., Marcus B. In: Introduction to Zeolite Science and Practice. van Bekkum H., Flanigen E. M., Jacobs P. A., Jansen J. C., editors. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2001. pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baerlocher C., Meier W. M., Olson D. H. Atlas of Zeolite Framework Types. 5th Ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sturm M., Brandl F., Engel. D., Hoppe W. Acta Crystallogr. B. 1975;31:2369–2378. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lehnert R., Seel F. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 1980;464:187–194. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rettig S. J., Storr A., Summers D. A., Thompson R. C., Trotter J. Can. J. Chem. 1999;77:425–433. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tian Y.-Q., Cai C.-X., Ji J., You X.-Z., Peng S.-M., Lee G.-H. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002;41:1384–1386. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020415)41:8<1384::aid-anie1384>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tian Y.-Q., Cai C.-X., Ren X.-M., Duan C.-Y., Xu Y., Gao S., You X.-Z. Chem. Eur. J. 2003;9:5673–5685. doi: 10.1002/chem.200304957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Masciocchi N., Bruni S., Cariati E., Cariati F., Galli S., Sironi A. Inorg. Chem. 2001;40:5897–5905. doi: 10.1021/ic010384+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang X.-C., Zhang J.-P., Chen X.-M. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2003;48:1531–1534. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang X.-C., Lin Y.-Y., Zhang J.-P., Chen X.-M. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;45:1557–1559. doi: 10.1002/anie.200503778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yaghi O. M., O’Keeffe M., Ockwig N. W., Chae H. K., Eddaoudi M., Kim J. Nature. 2003;423:705–714. doi: 10.1038/nature01650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zou X., Conradsson T., Klingsted M., Dadachov M. S., O’Keeffe M. Nature. 2005;437:716–719. doi: 10.1038/nature04097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang S. Y., Long L. S., Jiang Y. B., Huang R. B., Zheng L. S. Chem. Mater. 2002;14:3229–3231. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Masclocchi N., Ardizzoia G. A., LaMonica G., Maspero A., Sironi A. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2000:2507–2515. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Breck D. W. Zeolite Molecular Sieves. New York: Wiley; 1974. pp. 593–724. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kruk M., Jaroniec M., Sayari A. J. Phys. Chem. B. 1997;101:583–589. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao D., Huo Q., Feng J., Chmelka B. F., Stucky G. D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:6024–6036. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wong-Foy A. G., Matzger A. J., Yaghi O. M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:3494–3495. doi: 10.1021/ja058213h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chae H. K., Siberio-Perez D. Y., Kim J., Go Y. B., Eddaoudi M., Matzger A. J., O’Keeffe M., Yaghi O. M. Nature. 2004;427:523–527. doi: 10.1038/nature02311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Z., Han Y., Zhu L., Wang R., Yu Y., Qiu S., Zhao D., Xiao F.-S. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2001;40:1258–1262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sundberg R. J., Martin R. B. Chem. Rev. 1974;74:471–517. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.