Abstract

T cells are critical for the formation of intraabdominal abscesses by Staphylococcus aureus. We hypothesized that T cells modulate the development of experimental staphylococcal infections by controlling polymorphonuclear leukocyte (PMN) trafficking. In models of staphylococcal s.c. abscess formation, hindpaw infection, and surgical wound infection, S. aureus multiplied in the tissues of WT C57BL/6J mice and elicited a marked inflammatory response. CD4+ αβ T cells homed to the surgical wound infection site of WT animals. In contrast, significantly fewer S. aureus were recovered from the tissues of mice deficient in αβ T cells, and the inflammatory response was considerably diminished compared with that of WT animals. αβ T cell receptor (−/−) mice had significantly lower concentrations of PMN-specific CXC chemokines in wound tissue than did WT mice. The severity of the wound infection was enhanced by administration of a CXC chemokine and abrogated by antibodies that blocked the CXC receptor. An acapsular mutant was less virulent than the parental S. aureus strain in both the s.c. abscess and the surgical wound infection models in WT mice. These data reveal an important and underappreciated role for CD4+ αβ T cells in S. aureus infections in controlling local CXC chemokine production, neutrophil recruitment to the site of infection, and subsequent bacterial replication.

Keywords: capsular polysaccharide, abscess

Staphylococcus aureus is the causative agent of a range of serious human infections, including pneumonia, endocarditis, and sepsis (1). In addition, this organism is a major cause of localized infections, such as s.c. abscesses, impetigo, and surgical wound infections. The increasing prevalence of nosocomial and community-acquired S. aureus infections has prompted studies to better understand the host–pathogen interactions.

S. aureus produces a myriad of virulence factors that contribute to its ability to cause disease, allowing the organism to gain entry into tissues, evade the host immune system, attach to host cells, and secrete exoproteins and toxins. Cell wall components such as peptidoglycan, teichoic acids, and capsule, as well as adhesins, proteases, exoproteins, and exotoxins, all promote the virulence of this pathogen (2–4).

In contrast, less is known about the host response to S. aureus and how host factors influence the pathogenesis of staphylococcal infections. Animal models of staphylococcal infections have been used to investigate the interactions between S. aureus and the host. However, few recapitulate the major hallmarks of the disease as it occurs in humans, because a large S. aureus inoculum [>106 colony-forming units (cfu)] is necessary to initiate infection, and little bacterial replication occurs in vivo. The amount of inoculum needed to provoke disease can be reduced with the use of foreign bodies, such as Cytodex 1 beads (Sigma), to potentiate infection (5).

Polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) represent the host’s first line of defense against invasion by S. aureus and are a critical determinant in the outcome of staphylococcal infections (6). Depletion of PMNs in vivo before bacterial challenge results in overwhelming disease (7–9), and patients who are neutropenic or who have congenital or acquired defects in PMN function are highly susceptible to S. aureus infection (6). However, Gresham et al. (10) demonstrated that survival of S. aureus inside PMNs contributes to the pathogenesis of staphylococcal infection in a murine peritonitis model.

We have shown that T cells control the development of abscesses in an animal model of S. aureus intraabdominal abscess formation and that the S. aureus capsular polysaccharide (CP) activates CD4+ T cells in vitro (11). Because abscess formation depends on the recruitment of PMNs to the site of infection, we hypothesized that T cells control the pathogenesis of S. aureus infection by modulating the PMN response in vivo. In this study, we investigated the influence of T cells on the pathogenesis of S. aureus infections in three distinct animal models. Experiments in a clinically relevant surgical wound infection model showed that T cells modulate the development of staphylococcal wound infections by controlling local CXC chemokine production, and ultimately PMN migration to sites of infection. This work demonstrates that, although PMNs may be beneficial to the host at the outset of S. aureus infection, they may also play a deleterious role during the course of disease.

Results

Influence of T Cells in Subcutaneous Abscess Formation.

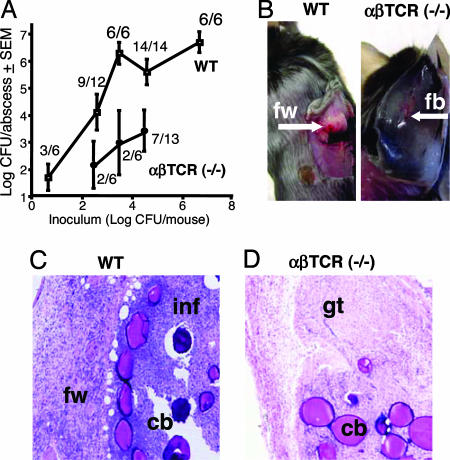

Previous studies (11, 12) have indicated that CD4+ T cells play a role in the development of S. aureus intraabdominal abscesses. To determine whether T cells might also influence other types of staphylococcal infection, WT C57BL/6J and αβ T cell receptor (TCR) (−/−) mice were challenged s.c. with 101 to 106 cfu of S. aureus PS80 [a serotype 8 CP (CP8) strain]. As shown in Fig. 1, WT mice exhibited a clear dose response at low inocula (≤3 × 103 cfu per mouse). The frequency of abscess formation reached 100% at inocula ≥3 × 103 cfu, and ≈106 cfu per abscess was recovered from these animals. Mice that were culture-negative developed smaller foreign-body responses that contained Cytodex beads only. Gross pathologic inspection of the abscesses in WT mice revealed large vascularized structures with a thick fibrin wall (Fig. 1B). Histologic analysis revealed that abscesses contained PMNs, bacteria, and Cytodex beads (Fig. 1C). Confocal microscopic examination of abscesses from WT mice demonstrated that CD3+ T cells had infiltrated the fibrin wall of these structures (data not shown). This observation is consistent with previous studies demonstrating that T cells home to and comprise the wall of intraabdominal abscesses (13).

Fig. 1.

Role of T cells in s.c. abscesses induced by S. aureus PS80. (A) Quantitative cultures of abscesses from WT or αβ TCR (−/−) mice were significantly different at inocula of 3 × 104 (P = 0.026) and 3 × 103 (P = 0.038) cfu per mouse. The number of animals that were culture-positive in each group is indicated. (B) WT mice challenged with S. aureus formed defined abscesses with a thick fibrin wall (fw). In contrast, αβ TCR (−/−) mice developed small foreign-body responses (fb). (C) Histological analysis showed fibrin-encased (fw) abscesses in WT mice and significant leukocyte infiltration (inf). Cytodex beads (cb) are visible in the abscess tissue. (D) The foreign-body response seen in the αβ TCR (−/−) mice consisted primarily of granulation tissue (gt).

At inocula ranging from 3 × 102 to 3 × 104 cfu, αβ TCR (−/−) mice had fewer culture-positive abscesses and significantly fewer cfu per abscess than WT animals (Fig. 1A). Most of the αβ TCR (−/−) mice challenged with <104 cfu were culture-negative. αβ TCR (−/−) mice that were culture-positive developed a tissue response that differed from that of a classic abscess. These structures were smaller and lacked a thick fibrin wall (Fig. 1B). Histologic analysis revealed that the structures were composed of hyperproliferative fibroblasts characteristic of granulation tissue found in a foreign-body response but lacked significant PMN infiltration (Fig. 1D).

Influence of T Cells in the Hindpaw Infection Model.

Rich and Lee (14) described an S. aureus infection model in the hindpaw of nondiabetic and diabetic mice. We inoculated a hindpaw of WT and αβ TCR (−/−) mice with 106 cfu of PS80 and euthanized the mice after 5 days. Quantitative culture results revealed that WT mice had significantly (P = 0.0178) more S. aureus recovered from the hindpaws than did αβ TCR (−/−) animals: 5.24 ± 0.43 vs. 2.19 ± 0.44 cfu/g of tissue, respectively (mean log10 cfu ± SEM).

Development of a Surgical Wound Infection Model.

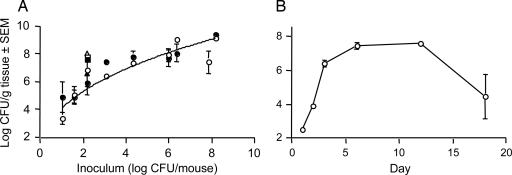

Our initial experiments were aimed at optimizing the inoculum needed to provoke a staphylococcal surgical wound infection in mice. Inoculation of surgical wounds with ≥103 cfu of S. aureus PS80 resulted in a localized purulent infection on day 3 that showed marked inflammation on gross pathological inspection. Challenge with inocula ≥106 cfu resulted in a severe and purulent infection. Tissues from mice inoculated with 101 to 108 cfu of PS80 were cultured quantitatively on days 3 or 6. As few as 10 cfu of S. aureus initiated infection, and the bacterial burden increased >1,000-fold over a 3-day period in mice challenged with 102 or 103 cfu of S. aureus strains PS80, Reynolds (a CP5 strain), or COL (a methicillin-resistant CP5 strain) (Fig. 2A). The tissue bacterial load was not significantly different between 3 and 6 days after inoculation. Animals infected with 2 × 106 cfu of S. aureus PS80 in the absence of a sutured wound yielded ≈1/100th as many S. aureus as animals with sutured wounds (data not shown). A time-course experiment in mice challenged with 103 cfu of S. aureus PS80 revealed that the bacterial burden in the wounded tissue achieved maximum levels (106 to 107 cfu/g of tissue) between 3 and 12 days after inoculation (Fig. 2B). The infection declined by day 18, when two of four mice had cleared the infection.

Fig. 2.

S. aureus wound infection model dose–response curve (A) and time course (B). (A) WT mice were challenged with increasing inocula of strain PS80 (circles), Reynolds (squares), or COL (triangles) and euthanized at either 3 days (open symbols) or 6 days (filled symbols). (B) WT mice were challenged with 103 cfu of S. aureus PS80 and euthanized at the designated time points.

Influence of T Cells on Surgical Wound Infections.

To determine whether T cells influenced the pathogenesis of S. aureus-induced surgical wound infections, initial experiments were performed with an inoculum of 40 cfu of strain PS80. Similar to our findings with the abscess and hindpaw infection models, WT mice had significantly (P = 0.0445) more S. aureus recovered from the infected wound tissue than did αβ TCR (−/−) animals on day 3: 5.05 ± 0.60 vs. 2.59 ± 0.76 cfu/g of tissue, respectively (mean log cfu ± SEM). Mice deficient in different T cell subsets were then used to determine the phenotype of T cells that contribute to the pathogenesis of S. aureus wound infections. CD8-deficient mice challenged with 102 cfu had 6.88 ± 0.67 log cfu/g of tissue recovered from wounds at day 3, similar to the bacterial burden recovered from WT mice (6.81 ± 0.23). In contrast, mice deficient in αβ TCR or CD4 or having T cells lacking the TCRα chain had significantly fewer bacteria at the wound site 3 days after inoculation with 102 cfu of S. aureus than did WT mice (Table 1). Likewise, the T cell-deficient mice had fewer S. aureus recovered from the wounds than did WT animals on day 6, and this difference was significant (P = 0.035) for the CD4 (−/−) mice. WT and T cell-deficient animals challenged with ≥103 cfu of S. aureus had similar numbers of bacteria recovered from the wounds on both days.

Table 1.

Bacterial burden in wounds of T cell-deficient mice challenged with 102 cfu of S. aureus

| Day | Log10 cfu of S. aureus per g of tissue |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | αβ TCR (−/−) | TCRα (−/−) | CD4 (−/−) | |

| 3 | 6.81 ± 0.23 (n = 7) | 4.89 ± 0.66 (n = 7; P = 0.028) | 2.85 ± 0.95 (n = 4; P = 0.027) | 5.34 ± 0.57(n = 11; P = 0.0327) |

| 6 | 5.90 ± 0.87 (n = 7) | 4.21 ± 0.70 (n = 8; P = 0.158) | 2.92 ± 1.06 (n = 4; P = 0.074) | 3.33 ± 0.65(n = 11; P = 0.035) |

Results are presented as mean ± SEM. P values are vs. WT.

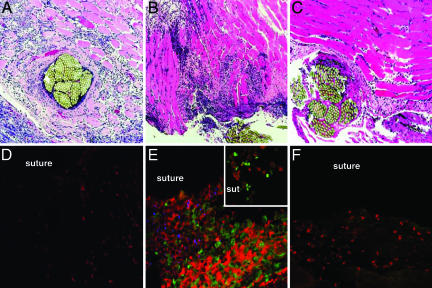

Histopathology of Surgical Wound Tissues.

Examination of the wound tissues from WT mice challenged with PBS revealed aspects of the normal host response to a foreign body. PMNs were detected at the suture site by 24 h after surgery. By day 3 the PMN infiltration was accompanied by a densely staining infiltrate of hyperproliferative fibroblasts associated with granulation tissue (Fig. 3A). This observation is consistent with the normal process of wound repair that follows tissue trauma. More granulation tissue and fewer PMNs were observed at the wound site by day 6 (data not shown), indicating that the normal wound healing process was under way.

Fig. 3.

Histopathology and confocal microscopy of wound tissues. (Magnification: ×100.) Wounds were inoculated with PBS or 102 cfu of S. aureus PS80 and harvested on day 3. Tissue sections were processed for histology (A–C) or stained with mAbs specific for PMNs (red) and αβ T cells (green) and polyclonal Abs to S. aureus PS80 (blue) for examination by confocal microscopy (D–F). PBS-challenged wounds (A and D) showed the influx of some PMNs and monocytes, but no T cells. Wounds inoculated with S. aureus (B and E) showed a marked inflammatory response characterized by infiltration of PMNs and mononuclear cells. (Inset) T cells were observed infiltrating to the infected suture site. Surgical wounds in αβ TCR (−/−) mice challenged with S. aureus (C and F) revealed a less intense cellular infiltrate with relatively few PMNs and mononuclear cells present.

Challenge of WT animals with 102 cfu of S. aureus resulted in numerous PMNs infiltrating the wound site 24 h after surgery. Additional PMNs entered the wound site by day 2 and were found around the suture and in the surrounding muscle tissue. Mononuclear cells were observed infiltrating the wound site on day 2. By day 3, wounds exhibited an intense, purulent infection with numerous PMNs and mononuclear cells visible near the suture and in the surrounding tissue (Fig. 3B). The cellular infiltrate in infected tissues was greater than that observed in PBS-challenged mice at each time point. S. aureus-infected wounds on day 6 were histologically similar to those from day 3, an indication that the host response had not abated. Mice challenged with 103 cfu of S. aureus PS80 exhibited a more severe infection than mice given 102 cfu, but the time course of histopathologic changes was similar (data not shown).

Histologic examination of surgical wound tissues from αβ TCR (−/−) mice on day 3 revealed less inflammation in response to challenge with 102 (Fig. 3C) or 103 cfu of S. aureus compared with WT animals. Tissues from αβ TCR (−/−) mice showed reduced PMN infiltration and fewer mononuclear cells around the suture site and in the surrounding muscle tissue compared with that seen in WT animals. Granulation tissue associated with normal wound repair was noted in tissues from αβ TCR (−/−) mice.

T Cells Traffic to S. aureus-Infected Wounds.

Confocal microscopy was used to investigate the types of cells that infiltrated the wound site during S. aureus infection. WT mice were challenged with PBS or 102 cfu of S. aureus PS80, and the wounds were harvested daily until day 6 after surgery. Mice challenged with PBS showed some PMN infiltration at the wound site, but no αβ T cells were observed on day 3 (Fig. 3D). Infiltration of PMNs occurred within the first 24 h of infection in WT mice challenged with S. aureus, whereas T cells could be detected by day 2 after inoculation. Cellular infiltration by T cells and PMNs achieved maximal levels on day 3 (Fig. 3E). PMNs, T cells, and bacteria were present around the sutures and in the surrounding muscle tissue. The αβ T cells in the wound tissues (Fig. 3E) stained positive for CD4 but not for CD8 (data not shown).

Confocal microscopic analysis of tissues from αβ TCR (−/−) mice challenged with 102 or 103 cfu of S. aureus PS80 confirmed our histologic findings that T cell deficiency alters the cellular host response. Compared with WT mice, αβ TCR (−/−) mice showed a mitigated inflammatory response in the wounds on day 3, with notably fewer PMNs and mononuclear cells present (Fig. 3F).

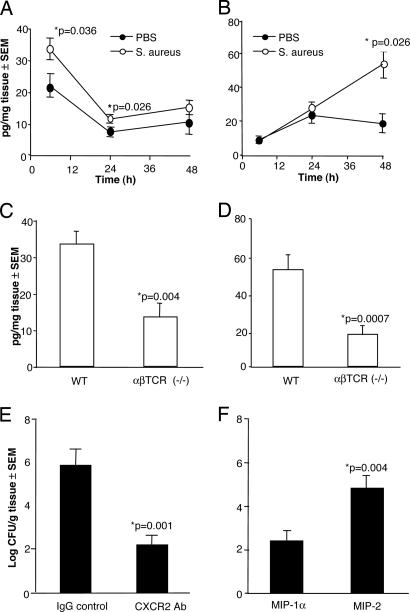

CXC Chemokine Response in Staphylococcal Wound Infections.

PMNs migrate to sites of infection in response to chemoattractants such as the CXC chemokines. Levels of keratinocyte-derived cytokine (KC/CXCL1) and macrophage inflammatory protein 2 (MIP-2/CXCL8) were assessed in wounds inoculated with 102 cfu of S. aureus PS80 or PBS at 6, 24, and 48 h after surgery. Challenge of WT mice with S. aureus resulted in significantly (P = 0.036) higher KC levels 6 h after challenge compared with mice given PBS (Fig. 4A). KC tissue levels diminished with time, reaching baseline levels by 24 h after inoculation. In contrast, the levels of MIP-2 reached a maximum at 48 h in the S. aureus-infected tissues (Fig. 4B), at which point the MIP-2 level was significantly (P = 0.026) greater than that found in control animals. No further increase in MIP-2 levels was observed in samples analyzed at 72, 96, or 120 h (data not shown). To determine the influence of T cells on CXC chemokine production in response to S. aureus wound infection, WT and αβ TCR (−/−) mice were challenged with 102 cfu of S. aureus PS80. KC concentrations in wound tissue from αβ TCR (−/−) mice were significantly (P = 0.004) lower at 6 h compared with tissue levels in the WT group (Fig. 4C). Likewise, MIP-2 concentrations were significantly (P = 0.0007) decreased in the αβ TCR (−/−) mice at 48 h compared with WT mice (Fig. 4D).

Fig. 4.

Role of chemokines in S. aureus wound infections. (A) WT mice challenged with 102 cfu of S. aureus PS80 showed increases in KC levels at 6 and 24 h compared with mice given PBS. (B) MIP-2 levels were significantly greater at the 48-h time interval in the S. aureus group than in the PBS group. (C) After challenge with 102 cfu of S. aureus PS80, peak tissue concentrations of KC were significantly lower in αβ TCR (−/−) mice than in WT mice at 6 h. (D) MIP-2 levels were significantly decreased in the αβ TCR (−/−) mice at 48 h. (E) Quantitative cultures in WT mice were performed on day 3 after challenge with 102 cfu of S. aureus and i.p. administration of antibodies 1 h before and 6 h after surgery. (F) αβ TCR (−/−) mice were challenged with 43 cfu of S. aureus PS80, and MIP-2 or MIP-1α (400 ng) was administered directly into the wound 4 and 24 h after surgery. Cultures were quantified on day 3.

Role of CXC Chemokines in S. aureus Wound Infections.

KC and MIP-2 bind to a common CXC receptor (CXCR2) on PMNs, and blockade of this receptor in vivo results in decreased PMN recruitment to sites of inflammation (15). Administration of CXCR2 antibodies to WT mice resulted in a significantly (P = 0.001) reduced bacterial burden in S. aureus-infected wounds compared with administration of an IgG control antibody (Fig. 4E).

The specific role of MIP-2 was addressed by challenging αβ TCR (−/−) mice with S. aureus PS80 and then treating them with a CXC chemokine (MIP-2) or a CC chemokine MIP-1 (MIP-1α/CCL3) 4 and 24 h after surgery. Administration of MIP-2 produced a significantly (P = 0.004) greater bacterial burden at the suture site than administration of the CC chemokine MIP-1α (Fig. 4F).

Role of the Capsule in the Pathogenesis of S. aureus Infections.

The capsule of S. aureus has been implicated as a virulence factor for this organism (16–19). CP8 activates CD4+ T cells in vitro, and activated T cells induce intraabdominal abscesses when transferred to naïve animals (11). Therefore, we assessed whether the type 8 capsule influenced the pathogenesis of s.c. abscess formation or experimental staphylococcal wound infection. The acapsular mutant RMS-1 was less virulent than the parental strain PS80 in both infection models (Table 2). WT mice inoculated with 102 or 103 cfu of RMS-1 had significantly (P < 0.05) fewer S. aureus recovered from the infection sites than mice challenged with strain PS80. In contrast, strain PS80 and mutant RMS-1 showed similar virulence in αβ TCR (−/−) mice inoculated with 102 cfu of S. aureus (mean log cfu/g of tissue ± SEM: 5.32 ± 0.31 and 4.84 ± 0.52, respectively). MIP-2 and KC concentrations in WT mice infected with the acapsular mutant RMS-1 were not significantly different from those in PS80-infected mice (data not shown).

Table 2.

The S. aureus capsule promotes virulence in mouse models of S. aureus s.c. abscess formation and surgical wound infection

| Inoculum, log10 cfu/mouse | Subcutaneous abscess |

Wound infection |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Log10 cfu of S. aureus per abscess |

P | Log10 cfu of S. aureus per g of tissue |

P | |||

| PS80 | RMS-1 (acapsular) | PS80 | RMS-1 (acapsular) | |||

| 3 | 6.29 ± 0.4 (n = 6) | 4.92 ± 0.41 (n = 6) | 0.049 | 7.01 ± 0.19 (n = 17) | 6.06 ± 0.34 (n = 20) | 0.021 |

| 2 | 3.7 ± 0.63 (n = 12) | 2.13 ± 0.51 (n = 14) | 0.070 | 6.36 ± 0.45 (n = 14) | 4.84 ± 0.52 (n = 28) | 0.013 |

Results are presented as mean ± SEM.

Discussion

An important aspect of the host innate immune response to S. aureus is opsonophagocytic killing by PMNs. The essential role of phagocytic killing in host clearance of S. aureus is apparent because patients who are neutropenic or have defects in PMN function suffer from recurrent staphylococcal infections. In contrast, little information is available on how various T cell populations influence the outcome of staphylococcal infections. We reported that the S. aureus CP activates CD4+ T cells in vitro and that activated T cells induce intraabdominal abscesses when transferred to naïve animals (11). These results led us to consider the T cell as an important mediator of the host response to this organism.

We evaluated the role of T cells in modulation of host innate immunity in three different animal models of S. aureus infection. Whereas WT mice formed well-defined abscesses at inocula as low as 103 cfu, αβ TCR (−/−) mice were impaired in their ability to develop defined abscesses. Few PMNs were noted in tissue sections from αβ TCR (−/−) mice, and significantly fewer bacteria were recovered from the infection site of the mutant animals compared with WT animals. Similarly, in the hindpaw infection model, challenge of αβ TCR (−/−) mice resulted in a significantly lower bacterial burden in the infected tissue than in WT animals. These data are concordant with the results of our earlier studies indicating that T cells control the development of S. aureus intraabdominal abscesses (11, 12).

These experimental findings were investigated in greater depth in a wound infection model that mimics S. aureus infection in a surgical setting. As few as 10 cfu initiated infection in this model, and bacterial numbers increased in vivo by 3 to 4 orders of magnitude. The infection remained localized; the mice did not become bacteremic even when >106 cfu were delivered to the wound.

Few studies have critically assessed the contribution of the host response to the pathogenesis of staphylococcal wound infections. Confocal microscopic analyses of S. aureus-infected wounds from WT mice confirmed histologic findings that PMNs infiltrated the wound tissue by 24 h after bacterial inoculation. αβ CD4+ T cells were observed at the wound site on day 2 and were abundant in the tissues by day 3. Compared with WT or CD8-deficient mice, fewer bacteria were cultured from the wound site of αβ TCR-, CD4-, and TCRα chain-deficient mice at 3 and 6 days after challenge with 102 cfu of S. aureus. A markedly reduced PMN infiltrate was observed at the suture site of αβ TCR-deficient mice compared with WT mice, suggesting that CD4+ αβ T cells contribute to the pathogenesis of staphylococcal wound infections by controlling PMN infiltration.

Because CXC chemokine levels were significantly lower in αβ TCR (−/−) mice than in WT animals, it is likely that T cells control PMN recruitment to the infected site through modulation of CXC chemokine levels and subsequent PMN migration to surgical wounds. Antibody blockade of the CXCR2, which binds both MIP-2 and KC in vivo, significantly reduced the bacterial burden at the infection site. Conversely, administration of MIP-2 directly into the wound at the time of challenge resulted in significantly greater bacterial counts in infected wounds than in wounds treated with the CC chemokine MIP-1α. These data clearly demonstrate that CXC chemokines modulate the pathogenesis of staphylococcal wound infections.

T cells have been shown to regulate neutrophil trafficking in the clinical setting as well. In patients suffering from acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, a severe drug hypersensitivity resulting in the formation of neutrophil-laden pustules in the skin, CD4+ T cells produce IL-8 and regulate neutrophilic infiltration to the inflammatory site (20). Phenotypic analysis of these CXC-producing T cells revealed that they express a chemokine receptor and cytokine profile associated with a T helper 1 effector memory phenotype. Further analysis is needed to identify the specific phenotypes of the T cells involved in regulating neutrophil trafficking during the course of an S. aureus wound infection.

Gresham et al. (10) demonstrated that local release of CXC chemokines promoted PMN migration but also resulted in a situation in which PMNs internalized but did not kill S. aureus. The authors postulate that CXC chemokines increase the persistence of live S. aureus within PMNs and provide the intracellular bacteria a niche where they are protected from competent phagocytes. We have shown in preliminary experiments that administration of MIP-2 into S. aureus-infected wounds of mice results in a greater number of viable bacteria internalized within PMNs than is the case in MIP-1α-treated animals (unpublished data). The potentially deleterious role of PMNs in staphylococcal disease is likely a function of the dual biologic activities displayed by CXC chemokines: they recruit PMNs to the infection site, but they may also delay PMN apoptosis and clearance by macrophages (21, 22). These events result in prolonged PMN infiltration and failure to clear replicating organisms, thus promoting chronic infection. This scenario is consistent with that of patients with periodontal disease, inasmuch as PMNs harvested from their oral abscesses or gingivitis sites show a significantly reduced ability to kill Porphyromonas gingivalis (23).

Both PMNs and T cells produce CXC chemokines, and local MIP-2 and KC levels are increased in animal models of S. aureus-induced brain abscesses and lung empyema (24–26). CD4+ T cells play a critical role in the pathogenesis of experimental S. aureus empyema (26), inasmuch as CD4 (−/−) mice had significantly fewer PMNs and lower concentrations of KC and MIP-2 in the pleural space than WT animals. Mice infected with S. aureus in our surgical wound model responded with early (6 h) KC production, whereas maximal MIP-2 production occurred at 48 h. These data are consistent with a previous study that showed a distinct temporal pattern of expression for these two functionally similar chemokines in a surgical injury model (27). The authors postulate that other inflammatory mediators at the wound site may differentially regulate the expression of KC and MIP-2. KC may be predominantly involved in directing initial PMN recruitment to the infection site, whereas MIP-2 may function in later aspects of the immune response to injury, e.g., CXC chemokines have been implicated in wound healing (28).

We showed previously (11) that S. aureus CP8 activates CD4+ T cells in vitro. Reports of other biological properties of CP8 are scant. The CP5 produced by S. aureus promotes virulence in numerous models of staphylococcal infection, including bacteremia, abscess formation, and septic arthritis (11, 17, 18, 29, 30), and protects the bacterium from opsonophagocytosis in vitro (17, 18, 29). We genetically modified the serotype 5 strain Reynolds to express CP8. Reynolds (CP8) was more virulent in a mouse bacteremia model and in phagocytic killing assays than an acapsular mutant but less virulent than Reynolds (CP5) (18). In the present study, the impact of S. aureus CP8 production was assessed in the s.c. abscess and the surgical wound infection models. The acapsular mutant RMS-1 was significantly less virulent than strain PS80 in each model. In contrast, the two strains showed equivalent virulence in αβ TCR (−/−) mice, which are unresponsive to S. aureus CP. Clearly, bacterial factors other than CP8 influence the outcome of staphylococcal infections because even the acapsular mutant caused infection at inocula >103 cfu (data not shown). S. aureus wall teichoic acid (produced by both strains) was as potent as CP8 in inducing intraabdominal abscesses in rats (11). Chemokine levels were equivalent in WT mice challenged with either RMS-1 or PS80. Other Gram-positive cell wall components common to both strains, such as peptidoglycan and lipoteichoic acid, have been shown to elicit a host inflammatory response in WT mice (31).

In summary, T cells modulate the pathogenesis of S. aureus infection in three different animal models. A low-inoculum, clinically relevant model of surgical wound infection was developed to study the role of T cells in disease progression and to characterize the host response to infection. The data demonstrate that T cells orchestrate the outcome of this infection through regulation of PMN infiltration and CXC chemokine production at the site. Our study underscores the importance of T cells in the control of certain staphylococcal infections, possibly through modulation of PMN function during the host response.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains.

S. aureus strains PS80, Reynolds, and COL are described in ref. 11. Mutant RMS-1 is an isogenic acapsular mutant of strain PS80 that was derived by allelic replacement mutagenesis with the temperature-sensitive vector pAP1.2 (18). Staphylococci were cultivated for 24 h at 37°C on Columbia agar (Difco) with 2% NaCl.

Mouse Models of S. aureus Infection.

Male WT C57BL/6J and congenic gene-deficient mice were obtained at 6–8 weeks of age from The Jackson Laboratory. Animal experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Harvard Medical School Standing Committee on Animals.

Subcutaneous abscess model.

This model is described in ref. 30. Mice were anesthetized with 100 mg/kg ketamine and 10 mg/kg xylazine, and the hair on their flanks was removed. The mice were injected s.c. in each flank with 0.2 ml of an S. aureus/Cytodex bead (Sigma) mixture containing 107 to 101 cfu. On day 4, the mice were euthanized and the abscesses were excised, homogenized, and cultured quantitatively.

Hindpaw infection model.

This model of S. aureus infection is described in ref. 14. A 10-μl suspension of S. aureus containing 106 cfu was injected into the plantar proximal aspect of the hindpaw. The mice were euthanized on day 5, and their hindpaw tissue was homogenized and cultured quantitatively.

Wound infection model.

In this model, mice were anesthetized and their right thighs were shaved and disinfected. The thigh muscle was exposed, and a 1-cm incision was made in the muscle to the depth of the bone. The incision was closed with one 4-0 silk suture, and 5 μl of an S. aureus suspension or PBS was introduced into the muscle incision under the suture. The skin was closed with four Prolene sutures (Ethicon, Somerville, NJ). At designated intervals after surgery, the mice were euthanized and the muscle tissue was excised, weighed, and homogenized, and S. aureus were cultured quantitatively.

Histologic and Confocal Analysis of Tissues.

Wound tissue was excised, fixed in formalin, embedded in paraffin, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin for microscopic examination. For confocal microscopy, tissue sections were dewaxed, permeabilized with 0.05% saponin, and incubated with normal goat serum to inhibit nonspecific binding. Tissue sections were stained with murine-specific antibodies (Ly-6G clone 1A8 for PMNs, clone H57-597 for αβ TCR, and GK1.5 for CD4; BD Pharmingen) or with MCD0820 for CD8α (CalTag, South San Francisco, CA). Slides were viewed with a multiphoton microscope with a krypton/argon laser (Bio-Rad) for standard confocal microscopy and a mode-locked titanium-sapphire laser (Spectra-Physics) for multiphoton imaging interfaced with a Zeiss Axiovert microscope.

Chemokine Analysis.

Wound tissues were excised and homogenized in 500 mM NaCl/50 mM Hepes, pH 7.4, containing 0.1% Triton X-100, 0.5 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 mM PMSF, and 0.02% NaN3. The homogenates were subjected to a freeze/thaw cycle and centrifuged at 6,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C. Concentrations of KC and MIP-2 in the cleared supernatants were determined by ELISA (R & D Systems).

Antibody and Chemokine Administration.

A goat polyclonal antibody to murine CXCR2 is described in refs. 15 and 32. The CXCR2 antibody (100 μg) or a control IgG antibody was administered i.p. to WT mice 1 h before and 6 h after surgery. Wounds were inoculated with 102 cfu of S. aureus PS80 and harvested on day 3 for quantitative culture. For chemokine administration, 400 ng of MIP-2 or MIP-1α (R & D Systems) was injected directly into the wound site of αβ TCR (−/−) mice 4 h and 24 h after inoculation with 30 cfu of S. aureus PS80. Tissues were harvested on day 3 for quantitative culture.

Statistical Analyses.

Quantitative culture results and tissue chemokine levels were compared by the Welch modification of the unpaired Student t test.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Vincent Carey for advice regarding statistical analyses. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants AI52397 (to A.O.T.) and AI29040 (to J.C.L.).

Abbreviations

- cfu

colony-forming units

- PMN

polymorphonuclear leukocyte

- CP

capsular polysaccharide

- TCR

T cell receptor

- KC

keratinocyte-derived cytokine

- MIP

macrophage inflammatory protein

- CXCR

CXC receptor.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Lowy F. D. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998;339:520–532. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199808203390806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheung A. L., Bayer A. S., Zhang G., Gresham H., Xiong Y. Q. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2004;40:1–9. doi: 10.1016/S0928-8244(03)00309-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pragman A. A., Yarwood J. M., Tripp T. J., Schlievert P. M. J. Bacteriol. 2004;186:2430–2438. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.8.2430-2438.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foster T. J. J. Clin. Invest. 2004;114:1693–1696. doi: 10.1172/JCI23825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ford C. W., Hamel J. C., Stapert D., Yancey R. J. J. Med. Microbiol. 1989;28:259–266. doi: 10.1099/00222615-28-4-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Veldkamp K. E., Van Kessel K. P., Verhoef J., Van Strijp J. A. Inflammation. 1997;21:541–551. doi: 10.1023/a:1027315814817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verdrengh M., Tarkowski A. Infect. Immun. 1997;65:2517–2521. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.7.2517-2521.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caver T. E., O’Sullivan F. X., Gold L. I., Gresham H. D. J. Clin. Invest. 1996;98:2496–2506. doi: 10.1172/JCI119068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lowrance J. H., O’Sullivan F. X., Caver T. E., Waegell W., Gresham H. D. J. Exp. Med. 1994;180:1693–1703. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.5.1693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gresham H. D., Lowrance J. H., Caver T. E., Wilson B. S., Cheung A. L., Lindberg F. P. J. Immunol. 2000;164:3713–3722. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.7.3713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tzianabos A. O., Wang J. Y., Lee J. C. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:9365–9370. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161175598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tzianabos A. O., Chandraker A., Kalka-Moll W., Stingele F., Dong V. M., Finberg R. W., Peach R., Sayegh M. H. Infect. Immun. 2000;68:6650–6655. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.12.6650-6655.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chung D. R., Kasper D. L., Panzo R. J., Chitnis T., Grusby M. J., Sayegh M. H., Tzianabos A. O. J. Immunol. 2003;170:1958–1963. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.4.1958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rich J., Lee J. C. Diabetes. 2005;54:2904–2910. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.10.2904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chung D. R., Chitnis T., Panzo R. J., Kasper D. L., Sayegh M. H., Tzianabos A. O. J. Exp. Med. 2002;195:1471–1478. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karakawa W. W., Sutton A., Schneerson R., Karpas A., Vann W. F. Infect. Immun. 1988;56:1090–1095. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.5.1090-1095.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thakker M., Park J. S., Carey V., Lee J. C. Infect. Immun. 1998;66:5183–5189. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.11.5183-5189.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watts A., Ke D., Wang Q., Pillay A., Nicholson-Weller A., Lee J. C. Infect. Immun. 2005;73:3502–3511. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.6.3502-3511.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O’Riordan K., Lee J. C. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2004;17:218–234. doi: 10.1128/CMR.17.1.218-234.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schaerli P., Britschgi M., Keller M., Steiner U. C., Steinmann L. S., Moser B., Pichler W. J. J. Immunol. 2004;173:2151–2158. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.3.2151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dunican A. L., Leuenroth S. J., Ayala A., Simms H. H. Shock. 2000;13:244–250. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200003000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kettritz R., Gaido M. L., Haller H., Luft F. C., Jennette C. J., Falk R. J. Kidney Int. 1998;53:84–91. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gainet J., Dang P. M., Chollet-Martin S., Brion M., Sixou M., Hakim J., Gougerot-Pocidalo M. A., Elbim C. J. Immunol. 1999;163:5013–5019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kielian T., Hickey W. F. Am. J. Pathol. 2000;157:647–658. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64575-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kielian T., Barry B., Hickey W. F. J. Immunol. 2001;166:4634–4643. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.7.4634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mohammed K. A., Nasreen N., Ward M. J., Antony V. B. J. Infect. Dis. 2000;181:1693–1699. doi: 10.1086/315422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Endlich B., Armstrong D., Brodsky J., Novotny M., Hamilton T. A. J. Immunol. 2002;168:3586–3594. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.7.3586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Devalaraja R. M., Nanney L. B., Du J., Qian Q., Yu Y., Devalaraja M. N., Richmond A. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2000;115:234–244. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00034.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nilsson I. M., Lee J. C., Bremell T., Ryden C., Tarkowski A. Infect. Immun. 1997;65:4216–4221. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.10.4216-4221.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Portoles M., Kiser K. B., Bhasin N., Chan K. H., Lee J. C. Infect. Immun. 2001;69:917–923. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.2.917-923.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fournier B., Philpott D. J. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2005;18:521–540. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.3.521-540.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hebert C. A., Chuntharapai A., Smith M., Colby T., Kim J., Horuk R. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:18549–18553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]