Abstract

Ribonucleotide reductase (RNR) from Chlamydia trachomatis is a class I RNR composed of proteins R1 and R2. In protein R2, the tyrosine residue harboring the radical that is necessary for catalysis in other class I RNRs is replaced by a phenylalanine. Active C. trachomatis RNR instead uses the FeIII-FeIV state of the iron cluster in R2 as an initiator of catalysis. The paramagnetic FeIII-FeIV state, identified by 57Fe substitution, becomes electron spin resonance detectable in samples that are frozen during conditions of ongoing catalysis. Its amount depends on the conditions for catalysis, such as incubation temperature and the R1/R2 ratio. The results link induction of the FeIII-FeIV state with enzyme activity of chlamydial RNR. Based on these observations, a reaction scheme is proposed for the iron site. This scheme includes (i) an activation cycle involving reduction and an oxygen reaction in R2 and (ii) a catalysis cycle involving substrate binding and turnover in R1.

Keywords: chlamydia, electron spin resonance, diiron carboxylate protein, species X

Chlamydiae are major pathogens that are responsible for a wide range of infections (1). They are obligate intracellular parasites of eukaryotic cells. Two species, Chlamydia trachomatis and Chlamydia pneumoniae, are well established human pathogens. Chlamydiae have a relatively small genome with limited metabolic capabilities, and they have evolved a very close relationship with the metabolism of the host (2). C. trachomatis can transport NTPs directly from the host cell, but not the dNTPs needed for DNA synthesis (3). dNTPs are made from NTPs by the enzyme ribonucleotide reductase (RNR). The RNR from C. trachomatis has been cloned and characterized (4).

RNR is the only enzyme that is capable of de novo synthesis of the four dNTPs. Catalysis involves free-radical chemistry. The RNRs are classified into three major classes that differ in metal and oxygen requirements as well as in the radical generation process. Class I RNRs, found in eukaryotes, DNA viruses, and certain bacteria (such as Escherichia coli), are composed of two homodimeric proteins, R1 (5, 6) and R2 (7, 8). For activity, this enzyme generally requires a free radical on a tyrosyl residue in protein R2. The tyrosyl radical is formed in a reaction between reduced iron and molecular oxygen in R2, concomitant with the formation of a diferric carboxylate cluster. Substrate binding in protein R1 is considered to initiate long-range transfer of the radical character from R2 to create an ultimate thiyl free radical on a cysteine residue adjacent to the substrate in R1, from which the substrate reaction then proceeds (9, 10). The long-range radical transfer has been shown to involve (with E. coli numbering) Cys-439, Tyr-730, and Tyr-731 in R1 and Tyr-356, Trp-48, Asp-237 in R2. In each protein, these residues are generally connected by hydrogen bonds, and they are considered to form a long-range electron transfer chain (or so-called radical transfer chain), operating to initiate or conclude catalysis. In normal class I RNRs, the radical harboring tyrosine close to the diiron cluster (Tyr-122 in E. coli) is the endpoint of the radical transfer chain in R2.

Genomes of several species of chlamydiae have been completely sequenced, among them that of C. trachomatis serovar 16 (2). This sequencing revealed the genes for a RNR homologue coding for proteins R1 and R2. The amino acid sequences of the R1 and R2 homologues suggest that the RNR of C. trachomatis belongs to class Ia. These are the only RNR genes found in the genome, and the corresponding enzyme is the one that was biochemically characterized by McClarty and coworkers (4).

A highly unusual feature of C. trachomatis RNR is that it has a phenylalanine residue at the position of the tyrosine where the free radical should be located in R2. Previous studies of the crystal structure of C. trachomatis protein R2 have verified the presence of the phenylalanine, which led us to suggest a different subclass, Ic, for this R2 protein (11). In the same study, we also showed that the iron/oxygen reconstitution reaction with protein R2 overexpressed in iron-depleted media (iron-depleted R2 or apoR2) gives rise to formation of a mixed valent diiron cluster, formally a FeIII-FeIV cluster, called intermediate or species X, but no tyrosyl free radical or any other amino acid-derived radical was found. In other class I RNRs, species X is observed as the immediate precursor to the stable tyrosyl radical (12–14). Intermediate X is best described as an antiferromagnetically coupled high-spin FeIII-FeIV cluster, although available data suggest a significant delocalization of spin onto the iron ligands (15–17). In C. trachomatis protein R2, the lifetime of species X formed by the iron/oxygen reaction with apoR2 was greatly enhanced by forming a complex with protein R1 and even more greatly enhance by adding the substrate to the complex (18).

Here, we report that under conditions of ongoing catalysis, species X is induced in the R2 protein, quantitatively dependent on temperature and on the presence of R1 protein. In contrast to the experiments reported in ref. 18, formation of the FeIII-FeIV cluster as observed here is not due to addition of iron to a solution containing apoprotein, but in the present experiments, the electron spin resonance (ESR) signal from the FeIII-FeIV site is induced in a regularly grown iron containing R2 protein (initially devoid of any ESR signal) by initiating catalysis by heating the sample from 4°C to 36°C with all components needed for catalysis present. These observations link the enzymatic activity of this RNR to the presence of species X. This study shows induced changes in the paramagnetic state of protein R2 related to ongoing catalysis in protein R1 in a class I RNR.

Results

Catalysis-Dependent Appearance of the Species X ESR Signal.

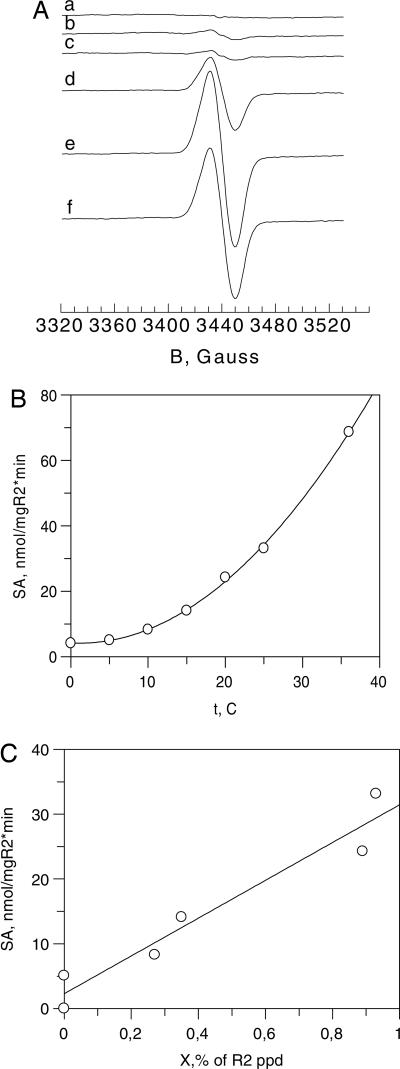

Chlamydial RNR demonstrates a moderate activity (maximum reported activity of 300 nmol of CDP per mg of R2 per min) (4), which was >20 times less than the activity of E. coli RNR (reported recently to be 6,990 nmol of CDP per mg of R2 per min) (19). The present studies mainly make use of an active preparation of C. trachomtis R2 (active R2 or iron-containing R2) with a high occupancy of iron (typically 1.8–1.9 Fe per polypeptide) but devoid of ESR signal (11). This preparation was incubated with a catalytically active mixture of R1, reductant, required allosteric regulators, and substrate at different temperatures. The samples were rapidly frozen in cold isopentane and investigated by ESR (Fig. 1A). The ESR spectra show the appearance of the g = 2 singlet signal characteristic of species X in amounts that increase with the incubation temperature up to 25°C (Fig. 1A, traces a–f). At 36°C, the amount of X observed corresponds to ≈0.08–0.1 per polypeptide chain. Control experiments showed that if R1 was left out from the incubation mixtures, no ESR signal could be seen after incubation at 36°C (data not shown). Repeating the experiments with lower R1 and R2 concentrations, which would be the same as those used in the activity measurements (10 μM R2 instead of 40 μM), gave rise to smaller induction of the ESR signal (maximum of ≈0.01 per polypeptide under otherwise similar conditions). At the same time, parallel activity measurements carried out as described in ref. 20 showed the increase of specific activity with increasing temperature in the physiological range (Fig. 1B). Fig. 1C links the results of observed induction of X with the specific activity at temperatures varying between 0°C and 25°C. Because of the uncertainty in the small amounts of induced X, the points are scattered, but there is a clear linear correlation between the two observables linked by temperature.

Fig. 1.

Induction of species X is linked with enzyme activity at different temperatures. (A) Induction of species X (the FeIII-FeIV state of protein R2) in the ESR samples containing the necessary components for the activity assay for C. trachomatis RNR at different temperatures. A mixture containing 40 μM iron-containing R2, 160 μM R1Δ1–248, 10 mM DTT, 2 mM ATP, 12.6 mM MgCl2, and 2 mM CDP in 50 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.5) was prepared at 0°C. The mixture was aliquoted to six ESR tubes on ice. The procedure took 1–2 min. The enzymatic reaction was started by raising the temperature. Each ESR tube was incubated for 7 min at different temperatures and then quickly frozen in cold isopentane. The X band ESR spectra were recorded at 45 K, modulation frequency of 100 kHz, modulation amplitude of 0.5 mT, and microwave power of 3 mW (nonsaturating conditions for species X). Each spectrum was accumulated for 8 min. Temperatures of incubation were as follows: 0°C for trace a, 10°C for trace b, 15°C for trace c, 20°C for trace d, 25°C for trace e, and 36°C for trace f. (B) The specific activity of chlamydial RNR (nmol of CDP converted to dCDP by 1 mg of iron-containing R2 protein in 1 min) as a function of the temperature of incubation. Each sample contained 10 μM iron-containing R2, 40 μM R1Δ1–248, 2 mM ATP, 12.6 mM MgCl2, 10 mM DTT, and 2 mM 3HCDP in 50 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.5). The samples were incubated for 7 min at the indicated temperatures. The curve is fitted arbitrarily with exponential shape. (C) The enzymatic activity at temperatures of 0°C, 5°C, 10°C, 15°C, 20°C, and 25°C (from B) related to the amount of induced species X (expressed as the percentage of polypeptide concentration) observed at each investigated temperature in samples with the same low concentration of enzyme (10 μM iron-containing R2 and 40 μM R1Δ1–248). The straight line is a linear fit to the data points.

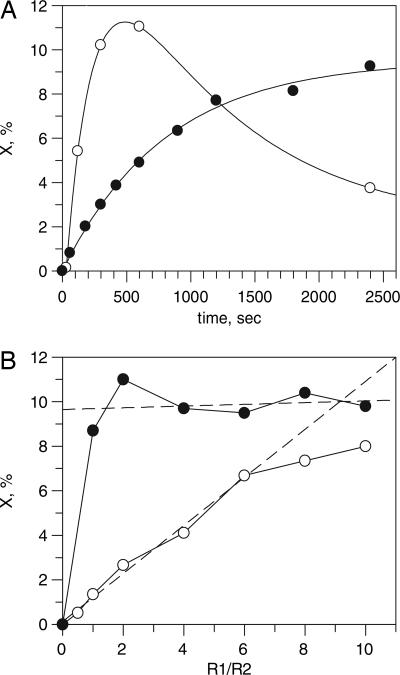

The amount of X induced in the course of the ongoing catalytic reaction reaches the maximum after 5–10 min of incubation at 36°C (Fig. 2A). The rate of formation of X is relatively slow (1.2 × 10−3 s−1 at 22°C) compared with the rate of formation after adding Fe2+ to apoprotein R2 (2.8 s−1 at 22°C) (18). This slow formation probably reflects the slow reduction of metR2 (with a diferric site) by DTT by means of R1 compared with the rapid incorporation of Fe2+ into apoprotein R2. The decay of X seen at 36°C is probably not due to lack of substrate, because an approximate estimation based on the specific activity reported above (Fig. 1B) shows that ≈75% of the substrate should remain after 7 min at 36°C. The decay may be due to temperature-dependent degradation of the enzyme. The rate of decay (0.8 × 10−3 s−1) is comparable to the rate of X decay (0.5 × 10−3 s−1) reported in ref. 18 for similar conditions. At 22°C, no decay of X was detected in the time frame investigated here (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Induction of species X during catalysis. (A) Time dependence of the induction of species X in the ESR samples containing the necessary components for the activity assay of C. trachomatis RNR. A mixture containing 40 μM iron-containing R2, 160 μM R1Δ1–248, 10 mM DTT, 2 mM ATP, 12.6 mM MgCl2, and 2 mM CDP in 50 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.5) was prepared at 0°C and aliquoted to ESR tubes as described in the legend of Fig. 1. Each ESR tube was incubated at 36°C (open circles) or 22°C (filled circles) for the indicated time and then quickly frozen in cold isopentane. The amount of X was estimated by double integration of the ESR signal and related to the concentration of R2 polypeptide. kform = 4.4 × 10−3 s−1 at 36°C and 1.2 × 10−3 s−1 at 22°C; kdecay = 0.8 × 10−3 s−1 at 36°C, which is comparable with kdecay = 0.5 × 10−3 s−1 at 36°C for reconstituted X reported in ref. 18. The conditions of ESR spectroscopy are the same as in Fig. 1A. (B) Dependence of the induction of species X on the R1/R2 ratio for varying conditions of incubation. Filled circles indicate samples containing 20 μM iron-containing R2, R1Δ1–248 in the indicated ratio to R2, 10 mM DTT, 2 mM ATP, 12.6 mM MgCl2, and 2 mM CDP in 50 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.5) incubated at 36°C for 10 min. Open circles indicate samples containing the same components incubated at 18°C for 5 min.

Species X Formation: Dependence on the R1/R2 Ratio.

The earlier reported dependence of the enzymatic activity on increasing amounts of the R1 protein (the R1/R2 ratio) (4) can also be seen for the induced species X but only for short incubation times and relatively low incubation temperature (Fig. 2B). If the incubation temperature and time are increased, formation of X becomes practically independent of the R1/R2 ratio (Fig. 2B). One explanation may be a very high stability of the R1/R2 complex once it is formed (formation should go faster at higher temperatures and higher R1 concentrations). The linear dependence on R1 concentration seen at lower temperatures (as well as the linear dependence of enzymatic activity observed in ref. 4 for the very dilute protein solutions normally used in activity assays) may reflect the probability of holoenzyme formation.

Verification of Species X by 57Fe Substitution.

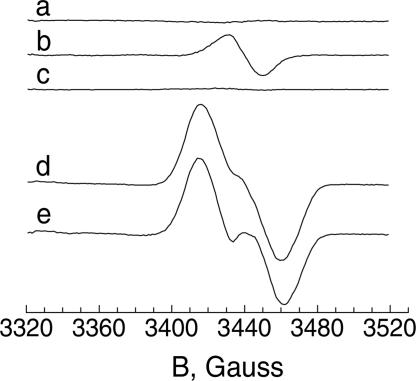

Because the ESR signal of the activity-induced species X is a relatively featureless singlet at g = 2, we verified its assignment to the FeIII-FeIV site by 57Fe substitution. An alternative preparation of the protein was overexpressed in iron-depleted media, which resulted in low iron occupancy, typically 0.7–0.8 Fe per polypeptide (iron-depleted R2). The enzymatic activity of this protein assayed as in ref. 20 was three times less than for R2 overexpressed in regular LB. After incubation of the iron-depleted R2 protein together with a catalytically active mix of protein R1, reductant, and necessary effectors at 0°C, no ESR signal was visible (Fig. 3, trace a). At 36°C, the ESR signal of species X (Fig. 3, trace b) induced by 7 min of incubation with the catalytically active mix was ≈30% of that induced in the sample containing R2 overexpressed in regular LB (Fig. 1A, trace f). To investigate the effects of 57Fe, the same iron-depleted R2 preparation was incubated with 57Fe, after which, the excess iron was removed. This reconstituted R2 was incubated with an active catalytic mix at 0°C for 7 min and did not show any ESR signal (Fig. 3, trace c). Then, the 57Fe-reconstituted protein R2 was incubated at 36°C with the catalytically active mix, and the ESR signal was recorded (Fig. 3, trace d). The corresponding ESR signal now exhibited 57Fe isotope-induced changes. Direct subtraction of the induced 56Fe-dependent signal (Fig. 3, trace d minus trace b) gives the spectrum of trace e in Fig. 3, with the characteristic 57Fe doublet (2.4 mT hyperfine coupling) of intermediate X (12, 15). The enzymatic activity of the protein was completely restored after this reconstitution (data not shown). Thus, the enzymatic activity and X induction under conditions similar to those of the assay are directly linked to the iron occupancy of the diiron carboxylate site in the chlamydial R2 protein.

Fig. 3.

Evidence for the attribution of the ESR signal appearing during the enzymatic reaction by C. trachomatis RNR to the FeIII-FeIV state of the diiron carboxylate cluster of protein R2 (species X). (Trace a) Iron-depleted R2 (40 μM), 160 μM R1, 10 mM DTT, 2 mM ATP, 12.6 mM MgCl2, and 2 mM CDP in 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5) were incubated for 7 min at 0°C. (Trace b) An aliquot of trace a was incubated for 7 min at 36°C. (Trace c) The same mixture as in trace a but with R2 preliminarily reconstituted with 57Fe; the excess of 57Fe was removed by gel filtration with a NAP-25 column (Sigma) and incubated for 7 min at 0°C. (Trace d) An aliquot of trace c incubated for 7 min at 36°C. (Trace e) The result of subtraction: trace d minus trace b. The two spectra in traces b and d had the double integrals 0.33 and 1 (arbitrary units), respectively.

Discussion

It should be emphasized that in our previous studies on chlamydial R2 (11, 18), the formation of the FeIII-FeIV state of the diiron site was observed after adding reduced iron to an aerobic iron-depleted preparation of protein R2, either alone or with R1 and the ingredients necessary for catalysis. The rates of formation and decay of the FeIII-FeIV state were found to be strongly dependent on the reaction conditions (18). Here, formation of the FeIII-FeIV state is not induced by adding iron to an iron-depleted preparation of R2 but by changing the temperature of a sample containing “normal” iron containing R2 in addition to the other ingredients needed for catalysis, so that catalysis may proceed. A priori, the emerging relatively featureless ESR signal seen in the present experiments could be due to an unknown paramagnetic species in the system. However, the observed 57Fe hyperfine splitting of this emerging ESR signal strongly supports its assignment to the FeIII-FeIV site.

Taken together, these results show that the activity of chlamydial RNR depends on the formation of species X, the FeIII-FeIV site in protein R2. The iron cluster is used as a storage place for the protected oxidation equivalent needed to initiate catalysis in the chlamydial class I RNR, thereby replacing the normal tyrosyl radical for this function. Induced by a reaction with reductant and oxygen in protein R2, species X has a lifetime that is long enough to respond to substrate binding and participate in the subsequent radical formation at R1, transferring it from the diiron site of the protein R2. It follows that this ESR signal is visible only during the part of the catalytic cycle when the radical is not present in the R1 protein, and it must survive the freezing procedure of the sample. In protein R1, the hypothetical thiyl and substrate radicals are still elusive. We conclude that at constant temperature, the induced ESR signal of species X is proportional to the amount of the enzyme that is in the phase of substrate binding or product release of the whole cycle of the RNR turnover.

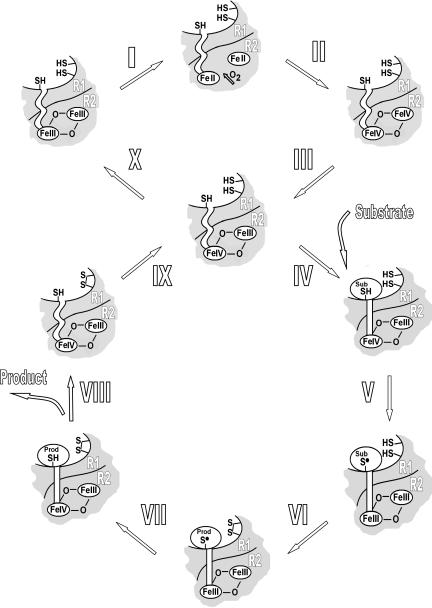

Fig. 4 is a proposed summary of the reaction pathway for chlamydial RNR. It shows two types of cycles: one involving activation (reduction and oxygenation of the iron site) and one involving catalysis, where an electron (radical) is transferred by means of the radical transfer chain from R1 to R2 after substrate binding and then back to R1 before product release. The radical transfer chain starts and ends at the iron site in R2, instead of at the tyrosyl radical as in normal class I RNRs. After product release, the lifetime of the FeIII-FeIV state in the holoenzyme is relatively long (18) and may allow the binding of a new substrate molecule and a new catalysis cycle before it decays, or the FeIII-FeIV state becomes reduced and the oxygenation reaction has to take place to reactivate the enzyme. A crucial aspect of the proposed model is that the R1/R2 binding has to be tight enough to isolate the high valent state of the iron site of R2 from the environment and that substrate binding reorganizes the radical transfer chain to facilitate transfer between R1 and R2.

Fig. 4.

Scheme depicting the proposed reaction cycles for the generation and role in catalysis of the FeIII-FeIV state of chlamydial RNR. The reaction steps are as follows. (I) Reduction of the diferric cluster of the enzyme. This step may be the slowest in the enzyme activation, which leads to loss of μ-oxo bridges. (II) Reduction of the diiron cluster of R2 protein is followed by reaction with molecular oxygen and formation of short-lived peroxo and FeIVFeIV (at least formally) high potential intermediates or transition states. (III) One-electron reduction of the diiron cluster, resulting in the formation of X. (IV) Substrate (NDP) binding accompanied by conformational changes facilitating electron transfer between the catalytic site in R1 (C672 or C439 in E. coli numbering) and the diiron cluster on R2 while protecting the diiron cluster from reduction by external electrons. (V) Thiyl radical (C672*) formation and reduction of the diiron cluster to the diferric state. (VI) Substrate turnover (9, 10) resulting in the oxidation of the cysteine pair C458 and C679 (C225 and C462 in E. coli numbering) and product (dNDP) formation. (VII) Product formation at the active site promotes back electron transfer from the diiron site in R2 to C672 in R1. This process remains facilitated while the product has not been released. (VIII) Product release restores the initial conformation of the R1/R2 complex, which allows only relatively slow diffusion of external electrons. (IX) The cysteine pair is reduced by the external reductant. In the presence of enough substrate, the enzyme starts the next turnover (new step IV). (X) In the case of a lack of substrate, the FeIII-FeIV site is reduced to the diferric state, ready for another oxygen activation reaction.

The present observations raise the question of whether the FeIII-FeIV state is involved also as an intermediate in the catalytic process in other functional class I RNRs. Our results suggest that it may well be and that, in the other class I RNRs, we see an elongation of the radical transfer pathway. The chlamydiae parasites have an evolutionary advantage in the present solution of storing and handling the extra oxidation equivalent without involving a tyrosyl radical. We previously suggested that the NO defense system of the host cell may be more effective toward an amino acid-derived free radical than toward an oxidized iron site (11). Another speculative reason could be that, in the present case, there is a tight enzyme complex and strong iron binding and therefore no need to involve the extra step of storing the oxidation equivalent one step farther away from the active site. A shorter chain of radical transfer for catalysis may be important for the function of the chlamydial enzyme.

Materials and Methods

Plasmids pET3a-CTR2 for C. trachomatis L2 R2 protein and pET3a-CTR1Δ1–248 for truncated C. trachomatis L2 R1 protein in E. coli (BL21) were obtained from the laboratory of Grant McClarty (University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, Canada).

Expression and Purification.

C. trachomatis protein R2 was grown and purified as described in ref. 21. For iron-depleted C. trachomatis protein R2 (apoR2), the extra chelation of iron from LB was performed by adding 100 μM EDTA to the media before overexpression with 0.5 mM isopropyl-1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside. The chelation procedure led to a decrease of the iron content in the protein by 60% compared with the C. trachomatis R2 protein overexpressed in regular LB. The iron content detected by a Sigma Diagnostics Iron reagents kit was 1.8–1.9 Fe per polypeptide monomer in active, iron-containing C. trachomatis R2 protein and 0.7–0.8 per polypeptide in iron-depleted protein (apoR2). Expression and purification of the C. trachomatis R1Δ1–248 protein were performed as described in ref. 4. The final purification was performed by using a HiLoad 16/10 Phenyl Sepharose column from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech. Using the C. trachomatis R1Δ1–248 protein instead of full-length R1 protein was dictated by its better stability, higher yield, and almost identical behavior in activity experiments (4).

Reconstitution of the Diiron Site in R2 Protein.

The reconstitution reactions of iron-depleted R2 protein with 57Fe2+ and O2 were performed by mixing oxygen-containing solution of the protein with an anaerobic ferrous ion solution in a volume ratio of 3:1. In this experiment, FeCl2 was used as a source of 57Fe2+ ions in a concentration ratio of three Fe2+ per C. trachomatis R2 monomer.

RNR Assay.

Aliquots (50 μl) of an assay mixture containing 50 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.5), 10 mM DTT, 2 mM ATP, 12.6 mM MgCl2, 2 mM [3H]CDP, 40 μM R1Δ1–248, and 10 μM R2 were incubated at different temperatures for 7 min. After incubation, the samples were processed as described earlier to obtain the amount of dCDP formed (20). The cpm detected for the assay containing only R1 protein was determined as a background and was subtracted from the cpm detected for the other samples.

ESR Measurements.

ESR spectra (9 GHz) were recorded on an ESP 300 X-band spectrometer (Bruker, Billerica, MA) with an ESR9 helium cryostat (Oxford Instruments, Oxon, U.K.) at 45 K, 3-mW microwave power, and 0.5-mT modulation amplitude. Spin quantitation was performed by double integration of ESR spectra recorded at nonsaturating microwave power levels by means of standard Bruker software and compared with a standard solution of 1 mM CuSO4 in 10 mM EDTA.

Acknowledgments

We thank G. McClarty for the kind gift of the plasmids to produce the proteins. This work was supported by a grant from the Swedish Research Council.

Abbreviations

- ESR

electron spin resonance

- RNR

ribonucleotide reductase.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Moulder J. W. Microbiol. Rev. 1991;55:143–190. doi: 10.1128/mr.55.1.143-190.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stephens R. S., Kalman S., Lammel C., Fan J., Marathe R., Aravind L., Mitchell W., Olinger L., Tatusov R.L., Zhao Q., et al. Science. 1998;282:754–759. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5389.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McClarty G., Tipples G. J. Bacteriol. 1991;173:4922–4931. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.16.4922-4931.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roshick C., Iliffe-Lee E., McClarty G. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:38111–38119. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006367200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Uhlin U., Eklund H. Nature. 1994;370:533–539. doi: 10.1038/370533a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Uhlin U., Eklund H. J. Mol. Biol. 1996;262:358–369. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nordlund P., Sjöberg B.-M., Eklund H. Nature. 1990;345:593–598. doi: 10.1038/345593a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nordlund P., Eklund H. J. Mol. Biol. 1993;232:123–164. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sjöberg B.-M. Struct. Bonding (Berlin) 1997;88:139–173. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stubbe J., van der Donk W.A. Chem. Rev. 1998;98:705–762. doi: 10.1021/cr9400875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Högbom M., Stenmark P., Voevodskaya N., McClarty G., Gräslund A., Nordlund P. Science. 2004;305:245–248. doi: 10.1126/science.1098419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bollinger J. M., Edmondson D. E., Huynh B. H., Filley J., Norton J. R., Stubbe J. Science. 1991;253:292–298. doi: 10.1126/science.1650033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andersson M. E., Högbom M., Rinaldo-Mathis A., Andersson K. K., Sjöberg B.-M., Nordlund P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:2346–2352. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yun D., Krebs K., Gupta G., Iwig D., Hyunh B. H., Bollinger J. M. Biochemistry. 2002;41:981–990. doi: 10.1021/bi011797p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sturgeon B. E., Burdi D., Chen S., Huynh B. H., Edmondson D. E., Stubbe J., Hoffman B. M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:7551–7557. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burdi D., Willems J.-P., Riggs-Gelasco P., Antholine W. E., Stubbe J., Hoffman B. M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:12910–12919. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Riggs-Gelasco P. J., Shu L., Chen S., Burdi D., Huynh B. H., Que L., Jr, Stubbe J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:849–860. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Voevodskaya N., Lendzian F., Gräslund A. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 2005;330:1213–1216. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.03.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fritscher J., Artin E., Wnuk S., Bar G., Robblee J. H., Kacprzak S., Kaupp M., Griffin R. G., Bennati M., Stubbe J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:7729–7738. doi: 10.1021/ja043111x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Engström Y., Eriksson S., Thelander L., Åkerman M. Biochemistry. 1979;18:2941–2948. doi: 10.1021/bi00581a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chabes A., Domkin V., Larsson G., Liu A., Gräslund A., Wijmenga S., Thelander L. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:2474–2479. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.6.2474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]