Abstract

To make a comprehensive study of tetracycline resistance determinant distribution in the genus Shigella, a collection of 577 clinical isolates of Shigella spp. and enteroinvasive Escherichia coli (EIEC) from a variety of geographical locations was screened to identify tetracycline-resistant strains. The 459 tetracycline-resistant isolates identified were then screened by PCR analysis to determine the distribution in these strains of tetracycline efflux resistance determinants belonging to classes A to E, G, and H that have been identified in gram-negative bacteria. Only classes A to D were represented in these strains. Although Tet B was the predominant determinant in all geographical locations, there were geographical and species differences in the distribution of resistance determinants. An allele of tet(A), designated tet(A)-1, was identified and sequenced, and the 8.6-kb plasmid containing determinant Tet A-1, designated pSSTA-1, was found to have homologies to portions of a Salmonella enterica cryptic plasmid and the broad-host-range resistance plasmid RSF1010. This allele and pSSTA-1 were used as epidemiological markers to monitor clonal and horizontal transmission of determinant Tet A-1. An analysis of serotype, distribution of tetracycline resistance determinants, and resistance profiles indicated that both clonal spread and horizontal transfer had contributed to the spread of specific tetracycline resistance determinants in these populations and demonstrated the use of these parameters as an epidemiological tool to follow the transmission of determinants and strains.

Shigellosis produces a substantial global disease burden, particularly for young children in developing countries; for civilian and military personnel traveling to countries where shigellae are endemic; and for populations in refugee camps, day care centers, and other institutional settings (15, 31). This disease is caused by the four Shigella species, S. dysenteriae, S. flexneri, S. boydii, and S. sonnei, all of which have multiple serotypes except S. sonnei. Antibiotic treatment is still the tool of choice to reduce disease severity and/or deaths from shigellosis (15, 20). However, Shigella spp. have progressively acquired resistance to most of the widely used and inexpensive antimicrobial agents (15, 26). There have been many studies on the resistance profiles of Shigella strains using phenotypic antimicrobial susceptibility tests such as disk diffusion (4, 13, 14, 19, 23, 31), but there have been no recent or comprehensive studies on the molecular epidemiology of specific resistance determinants in this genus.

Tetracyclines have been used extensively since the late 1940s as broad-spectrum inexpensive antibiotics that are effective against a wide variety of diseases in humans, animals, and plants. However, resistance to tetracycline has increased dramatically since the first appearance of resistance in 1953 in S. dysenteriae (6). The transmissibility of resistance in bacterial populations can take place by either clonal spread of particular strains or horizontal transfer of resistance determinants by plasmid- or transposon-mediated conjugation (2). Most tetracycline resistance determinants, defined as genetic units which contain both structural and regulatory genes involved in resistance (18), have been found on resistance plasmids or transposons, making gene transfer the likely method of acquiring resistance. The mechanisms of resistance have been well characterized, and the proteins have been classified into those that affect the energy-dependent efflux of tetracycline or allow ribosomal protection from its action (6). The classes of resistance determinants have been identified on the basis of DNA-DNA hybridization using structural genes as probes under stringent conditions (≤80% sequence identity) and in many cases subsequent DNA sequencing (6). Tetracycline efflux resistance determinants belonging to classes A to E, G, and H have been described in gram-negative bacteria, with classes A to E and G found in gram-negative enteric bacteria and class H found in species of Pasteurella and Mannheimia, which infect food-producing animals (6, 12). Molecular techniques such as PCR assays that identify the Tet resistance determinants are a valuable tool for epidemiological studies of resistance, providing important epidemiological information about the transmission of these genes through bacterial populations and the geographical and temporal spread of particular clones and allowing discrimination between clonal spread and horizontal transfer of resistance determinants (1, 5, 8, 11, 16, 30). Recent studies on gram-negative bacteria have examined the distribution of specific Tet determinants using genotypic detection assays (3, 5, 7, 11, 16, 21, 22, 27). However, only one paper (22), which included only 33 strains isolated in Mexico City, Mexico, in 1978 to 1979, has studied the distribution of these determinants in Shigella spp.

A more comprehensive study of Tet determinants in this genus was an important goal of this study, which focused on examining by PCR analysis the distribution of Tet determinants in 459 serotyped Shigella and enteroinvasive Escherichia coli (EIEC) clinical isolates (the latter of which show the same invasive phenotype characteristic of shigellae) from several geographical locations in four continents and in countries in various stages of development. The objectives of this study were (i) to examine the geographical and species-specific distribution of Tet determinants in these clinical isolates and (ii) to determine if the distribution of the determinants is due to clonal spread and/or horizontal transfer. Detection of horizontal gene transfer usually requires detection of an identical or unique marker in different species. During these studies, an allele of tet(A), designated tet(A)-1, was identified, and the plasmid containing it (pSSTA-1) was characterized. These two markers were then used as epidemiological tools to track the clonal and horizontal transmission of determinant Tet A-1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Source of isolates and serotyping analysis.

Shigella and EIEC samples were collected from the sources shown in Table 1. Sample collections described in previous studies are referenced in Table 1. Bacterial strains are clinical specimens isolated from stool samples from patients with diarrhea, cultured and serotyped using standard methods (10). All available samples were included in this study. The samples from Peru, Vietnam (13), and Bangladesh (13) were obtained from rural or village areas as part of studies of community-acquired diarrhea. The specimens from Thailand were isolated from patients with diarrhea from both rural and urban areas (12, 13). Patients included children from the areas of endemicity of Thailand as well as adults and children from the tourist and military populations. The samples from Somalia from 1992 to 1993 were obtained from clinical isolates from military personnel deployed to the area (29). The samples from Egypt were obtained from clinical isolates from a study of pediatric enteric diseases. The time period of collection and the distribution of the four species of Shigella and EIEC are also given in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Origin, source, and species of strains used in this study

| Location | Yr | Sourcea (reference) | Total no. of isolates | % Tetr |

S. flexneri

|

S. sonnei

|

S. dysenteriae

|

S. boydii

|

EIEC

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total no. of isolates | % Tetr | Total no. of isolates | % Tetr | Total no. of isolates | % Tetr | Total no. of isolates | % Tetr | Total no. of isolates | % Tetr | |||||

| USA and Canada | 1994-1995 | CDC | 10 | 100 | 10 | 100 | —b | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Thailand | 1986-1993 | AFRIMS (12) | 30 | 93 | 25 | 96 | 5 | 80 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Thailand | 1993-1996 | AFRIMS (13) | 191 | 81 | 95 | 92 | 29 | 79 | 23 | 100 | 2 | 100 | 42 | 48 |

| Peru | 1985-1986 | CH | 12 | 83 | 12 | 83 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Somalia | 1983 | WRAIR | 11 | 100 | 4 | 100 | 4 | 100 | 3 | 100 | — | — | — | — |

| Somalia | 1992-1993 | ORH (29) | 7 | 100 | 2 | 100 | — | — | 5 | 100 | — | — | — | — |

| Vietnam | 1999 | AFRIMS (13) | 236c | 84 | 165 | 88 | 39 | 69 | 6 | 50 | 23 | 83 | — | — |

| Bangladesh | 1999 | AFRIMS (13) | 35 | 60 | 31 | 58 | — | — | 1 | 0 | 3 | 100 | — | — |

| New York | 1971-1974 | WRAIR | 10 | 20 | — | — | 10 | 20 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Egypt | 1998-1999 | AH | 35 | 51 | 23 | 57 | 4 | 100 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 50 | — | — |

| Total | 577 | 80 | 367 | 86 | 91 | 70 | 44 | 77 | 30 | 83 | 42 | 48 | ||

Source abbreviations are as follows: AFRIMS, Armed Forces Research Institute of the Medical Sciences, Bangkok, Thailand; CDC, Centers for Disease Control, Atlanta, Ga.; CH, Cayetano Heredia, Lima, Peru; ORH, Operation Restore Hope, Joint Forward Laboratory, Mogadishu, Somalia (obtained from the NMRC [Naval Medical Research Center, Silver Spring, Md.]); WRAIR, Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, Silver Spring, Md; AH, Abu Homos, Egypt, field site used for study of pediatric enteric diseases by Naval Medical Research Unit, Cairo, Egypt) (obtained from the NMRC). Nine of the strains from New York were obtained by the WRAIR collection from the Willowbrook State School, Staten Island, N.Y. and one was from the Mary Bassett Institute, Cooperstown, N.Y.

—, no samples for species from that source.

Three of these samples were typed as Shigella, but the serotype was unknown.

Resistance to tetracycline and other antimicrobials.

Tetracycline resistance was originally determined in the isolates by the disk diffusion method (4). Maintenance of tetracycline resistance was confirmed by plating on agar plates containing 15 μg of tetracycline per ml. Resistance to other antimicrobials tested was originally determined by disk diffusion and confirmed by plating strains on agar plates containing trimethoprim (20 μg/ml), ampicillin (100 μg/ml), streptomycin (300 μg/ml), or chloramphenicol (25 μg/ml).

PCR reagents, conditions, and primers.

Tet determinants of classes A to E, G, and H were detected by PCR analysis (GeneAmp PCR system 9600; PE Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) with primers made on a 394 DNA/RNA Synthesizer (PE Biosystems). Primers were either designed based on sequences available from GenBank using the Primerselect software program (Lasergene, Madison, Wis.) or were obtained from published primer sequences as shown in Table 2. Expected amplicon size and control strains are also indicated. There are three reverse primers to differentiate tet(A) and tet(A)-1: (i) Tet AR (CTG CCT GGA CAA CAT TGC TT), which amplifies both genes (10); (ii) Tet AR2 (GTG CAA CGG GAA TTT GAA G), which amplifies only tet(A)-1 (derived from accession number AJ307714 and AF502943); and (iii) Tet AR3 (GGC ATA GGC CTA TCG TTT CCA), which amplifies only the tet(A) gene found in Tn1721 (X61367). Additional primers used for identifying resistance genes on the resistance plasmid containing Tet A-1 were (i) sul1, 5′-CAT CAT GAA ACG GAT CAC CG-3′; (ii) sul2. 5′-AGC GCC GCC AAT ACC GCC AG-3′; (iii) sul3, 5′-GCG CTC ACA GGC CGT GGT CC-3′; (iv) str1, 5′-TGA CTG GTT GCC TGT CAG AGG-3′; (v) str2, 5′-CCA GTT CTC TTC GGC GTT AGC A-3′; (vi) str3, 5′-CGC CTG TTT TTC CTG CTC AT-3′; (vii) str4, 5′-CCA TCC GCG TTC CAA GCT GC-3′); (viii) aadA, 5′-ACC TTT TGG AAA CTT CGG CT; and (ix) aadArev, 5′-TTT CAT CAA GCT TTA CGG TCA CCG-3′. These primers were derived from sequences found in accession numbers AB076707 (Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Choleraesuis cryptic plasmid for primers sul1, sul2, and sul3), M28829 and reference 28 (plasmid RSF1010 for primers str1, str2, str3, and str4), and X12870 and reference 25 (transposon Tn21 aadA-sul1 region for primers aadA and aadArev). Templates for PCR analysis were prepared by spinning down 1-ml overnight cultures, resuspending the pellet in 300 μl of sterile distilled water, boiling for 10 min, and centrifuging the sample for 2 min to pellet debris. For a 25-μl PCR mixture, 2 μl of the supernatant was used. The reaction mixture included 2.5 μl of 10× PCR buffer (Life Technologies, Grand Island, N.Y.), 0.75 μl of 50 mM MgCl2, 0.5 μl of 10 mM deoxytriphosphates mix (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, Ind.), and 0.25 μl of Taq DNA polymerase (Life Technologies) at 5 U/μl. Reactions were performed in a Perkin-Elmer GeneAmp PCR system 9600 using the cycling parameters of an original denaturation step of 94°C for 1 min; followed by 25 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s; and ending with a cycle of 72°C for 5 min. Reaction products were analyzed by gel electrophoresis on 0.8% agarose gels using 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA buffer.

TABLE 2.

PCR primers used in identification of tetracycline resistance determinants

| Resistance determinant | PCR primer | Sequences (5′ to 3′) | Expected size (bp) | Control strain | Primer or sequence reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tet A | F | GTA ATT CTG AGC ACT GTC GC | 956 | S. flexneri X SPH807 | 10 |

| R | CTG CCT GGA CAA CAT TGC TT | ||||

| R2 | GTG CAA CGG GAA TTT GAA G | 1,168 | S. sonnei SPH1482 | This study | |

| R3 | GGC ATA GGC CTA TCG TTT CCA | 1,202 | This study | ||

| Tet B | F | CTC AGT ATT CCA AGC CTT TG | 535 | S. flexneri 1 NIH1220 | 10 |

| R | CTA AGC ACT TGT CTC CTG TT | ||||

| Tet C | F | TCT AAC AAT GCG CTC ATC GT | 588 | E. coli DH5α (pBR322) | 10 |

| R | GGT TGA AGG CTC TCA AGG GC | ||||

| Tet D | F | AAA CCA TTA CGG CAT TCT GC | 787 | E. coli DH5α (pSL106) | 24 |

| R | GAC CGG ATA CAC CAT CCA TC | ||||

| Tet E | F | GTG ATG ATG GCA CTG GTC AT | 1,198 | E. coli HB101 (pSL1504) | 10 |

| R | CTC TGC TGT ACA TCG CTC TT | ||||

| Tet G | F | CAG CTT TCG GAT TCT TAC GG | 844 | E. coli HB101 (pJA8122) | 24 |

| R | GAT TGG TGA GGC TCG TTA GC | ||||

| Tet H | F | GCT CCT ATT CTA GGA CGA T | 933 | E. coli DH5α (pVM112) | 11 |

| R | ACA GAC CAT CCC AAT AAG CGA CG |

DNA hybridization techniques.

PCR products for Tet determinants were verified for specificity by Southern hybridization. PCR products from control strains and several strains positive for a specific determinant were subjected to agarose electrophoresis, blotted onto Biodyne A nylon membrane (Life Technologies), and probed with 32P-radiolabeled probes derived by PCR from control strains for Tet determinants A to E, G, and H using standard hybridization techniques. Strains and/or plasmids used for amplification of these probes were as follows: EIEC strain SPH 2148-1, Tet A; S. flexneri 1 strain NIH 1220 and strain XL1-Blue containing Tn10 (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.), Tet B; plasmid pBR322, Tet C; plasmid pSL106, Tet D; strain HB101/pSL1504, Tet E; strain HB101/pJA8122, Tet G; and DH5α/pVM111, Tet H.

Plasmid manipulations.

Plasmid purification of overnight 5-ml cultures of Shigella strains was done using miniprep kits (Qiagen, Inc., Santa Clarita, Calif.). Presence of plasmid DNA was confirmed by agarose gel electrophoresis. An aliquot of these preparations was then electroporated into E. coli DH5α and plated on tetracycline-Luria broth agar plates to isolate plasmids conferring tetracycline resistance. Restriction endonuclease analysis of plasmid DNA isolated from these clones using Qiagen midiprep kits was performed using 0.8% agarose gel electrophoresis.

DNA sequencing analysis.

DNA sequence analysis was used to confirm the sequence of Tet A-1 and to confirm the identification of the Tet D determinants present in some of the isolates (see Results). One to two other PCR products were amplified from strains containing Tet A, B, and C using the class-specific primers described above and partially sequenced to verify identification. Tet D determinants were amplified and sequenced using primers based on GenBank accession number L06798. The plasmid harboring Tet A-1, designated pSSTA-1, was purified from S. sonnei strain SPH-1482, a clinical isolate from Thailand, and a 4.67-kb BglII-KpnI fragment containing Tet A-1, which includes structural gene tet(A)-1 and regulatory gene tetR(A), was cloned into pUC18 (pTA-1). Initial sequencing used the M13 forward and reverse universal primers. Further sequencing of both strands of Tet A-1 was performed with primers based on a previously reported Tet A sequence (AJ307714). The Primerselect software program (Lasergene) was used for all oligonucleotide design during sequencing experiments. Nucleotide sequence determination was performed by the dideoxychain termination method using the Applied Biosystems International (Foster City, Calif.) PRISM dichloRhodamine Dye Terminator sequencing kit with AmpliTaq DNA polymerase. DNA sequencing reactions were analyzed on an Applied Biosystems International 377XL automated DNA sequencer. Sequence data were edited and assembled into contiguous sequences using Seqman (Lasergene).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers. The Tet D sequences have been deposited in GenBank and assigned accession numbers AF467071 to AF467078. The Tet A-1 sequence of S. sonnei strain SPH-1482 has been deposited in GenBank (AF502943).

RESULTS

Identification of tetracycline-resistant isolates.

The original collection of 577 clinical isolates obtained from a variety of geographical locations was screened for tetracycline resistance. A total of 459 strains from this collection (80%) were resistant to tetracycline. A summary for each location and time period including the total number and the percentage of tetracycline-resistant isolates for each serogroup is shown in Table 1. Strains reported in other studies are referenced. From this table, it is apparent that the New York samples from 1971 to 1974 had by far the lowest percentage of resistant samples (20%), which is consistent with the observation that resistance to tetracycline has increased dramatically since its introduction in the 1940s. Egypt and Bangladesh also have a lower percentage of tetracycline-resistant S. flexneri isolates compared to other localities. The EIEC strains from Thailand also showed a lower percentage of tetracycline-resistant strains (48%). Since resistance patterns can be used as a clonal marker, the rates of resistance against four other antimicrobial agents (streptomycin, ampicillin, trimethoprim, and chloramphenicol) were determined for tetracycline-resistant shigellae and EIEC isolates.

Identification of tetracycline resistance determinants by PCR analysis.

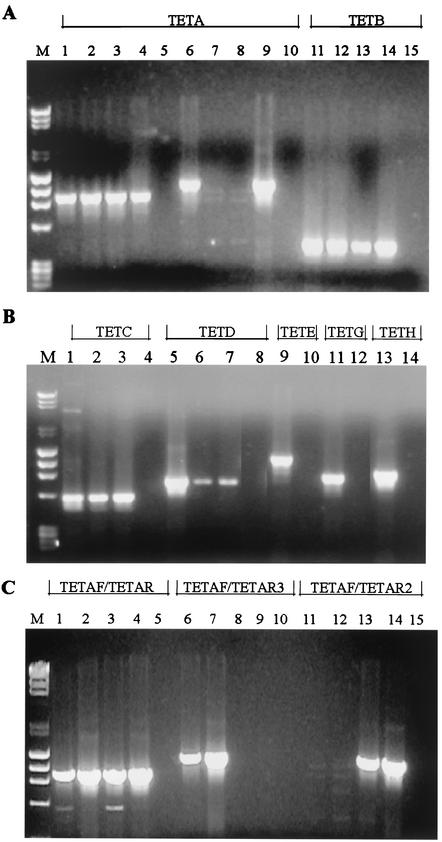

PCR primers specific for tetracycline resistance determinants A to E, G, and H were designed to give PCR products from the positive control strains. Amplification products using these primers with the control strains and a negative control strain (sensitive to tetracycline) are shown in Fig. 1A and B. Primers were also tested against control strains positive for the other determinants to eliminate the chance of cross-reactivity (data not shown). These primers were then used to screen the tetracycline-resistant isolates for the presence of these determinants. Only primers for classes A to D gave products when the clinical isolates were screened. PCR products from four to five samples of tetracycline classes A to D were probed with radiolabeled DNA amplified from control strains of Tet determinants A to D. These results confirmed the Tet identification in all cases, and there was no indication of nonspecific amplification of the determinants (data not shown).

FIG.1.

PCR products of tetracycline resistance determinants A to E, G, and H from positive and negative control strains and clinical isolates. Primers and positive control strains used are shown in Table 2. Negative control strains used were the tetracycline-sensitive strain S. sonneiSPH-2274 (A and B) and the tetracycline-sensitive strain S. flexneri serotype 6 SPH-1484 (C), both from Thailand. PCR analysis was done as described in Materials and Methods, and products were viewed using 0.8% agarose gel electrophoresis. (A) Lane M, molecular weight markers; lane 1, S. sonnei strain SPH-1482 (Tet A-1); lane 2, S. flexneri X strain SPH-810 (Tet A); lane 3, S. flexneri X strain SPH-1466 (Tet A); lane 4, S. sonnei strain SPH-788 (Tet A-1); lane 5, SPH-2274; lane 6, SPH-1482; lane 7, SPH-810; lane 8, SPH-1466; lane 9, SPH-788; lane 10, SPH-2274; lane 11, S. flexneri 1 strain NIH 1220; lane 12, S. dysenteriae 1 strain SPH-1351; lane 13, S. dysenteriae 1 strain SPH-1350C3; lane 14, S. flexneri 1 strain vn-41; lane 15, SPH-2274. Tet A primers Tet AF and Tet AR (lanes 1 to 5), Tet A primers Tet AF and Tet AR2 (lanes 6 to 10), and Tet B primers Tet BF and Tet BR (lanes 11 to 15) were used. (B) Lane M, molecular weight markers; lane 1, pBR322; lane 2, EIEC strain SPH-165321; lane 3, S. flexneri strain vn-nb7; lane 4, SPH-2274; lane 5, pSL106; lane 6, S. sonnei strain AS-14; lane 7, S. sonnei strain SPH-788; lane 8, SPH-2274; lane 9, pSL1504; lane 10, SPH-2274; lane 11, pJA8122; lane 12, SPH-2274; lane 13, pVM112H; lane 14, SPH-2274. Tet C primers Tet CF and Tet CR (lanes 1 to 4), Tet D primers Tet DF and Tet DR (lanes 5 to 8), Tet E primers Tet EF and Tet ER (lanes 9 and 10), Tet G primers Tet GF and Tet GR (lanes 11 and 12), and Tet H primers Tet HF and Tet HR (lanes 13 and 14) were used. (C) Lane M, molecular weight markers; lane 1, S. flexneri X strain SPH-810 (Tet A); lane 2, EIEC strain SPH-2148-1 (Tet A); lane 3, S. sonnei strain WS007980 (Tet A-1); lane 4, S. sonnei strain SPH-2357A4 (Tet A-1); lane 5, SPH-1484, all with Tet AF and Tet AR primers. Lanes 6 to 10 show the same strains using Tet AF and Tet AR3 primers. Only the strains with the Tn1721 Tet A (lanes 6 and 7) have a PCR product. Lanes 11 to 15 show the same strains using Tet AF and Tet AR2 primers. Only the strains containing Tet A-1 (lanes 13 and 14) have a PCR product.

One of our resistant isolates (S. sonnei strain SPH-1482 from Thailand) did not produce a PCR product with any of the Tet specific primers used initially. The Tet determinant from this strain was cloned and sequenced (see Materials and Methods). The sequence of the structural gene was found to be an allele of tet(A) and was designated tet(A)-1 (17; S. Levy, personal communication). The determinant containing tet(A)-1 was designated Tet A-1, which includes both the structural gene tet(A)-1 and the regulatory gene tetR(A) that is identical to the regulatory gene found in Tet A. The nucleotide variation in tet(A)-1 occurred in the last 28 nucleotides (changing nine carboxy-terminal amino acids of the protein and including the stop codon) and in the 3′ flanking region (see below). To better refine our PCR primers and to test the usefulness of this allele as an epidemiological tool, a reverse primer specific for the variant part of the coding region of the allele was synthesized (Tet AR2), and the Tet A strains previously identified with primers Tet AF and Tet AR (11) (Table 2) were tested for the presence of Tet A-1. An additional primer specific for the 3′ end of tet(A) found in Tn1721 (Tet AR3) was also synthesized to differentiate between strains harboring Tet A and Tet A-1 (Fig. 1C). This assay was used to determine the distribution of the two alleles of tet(A) in the clinical isolates (see below).

Resistance determinants by species and locality.

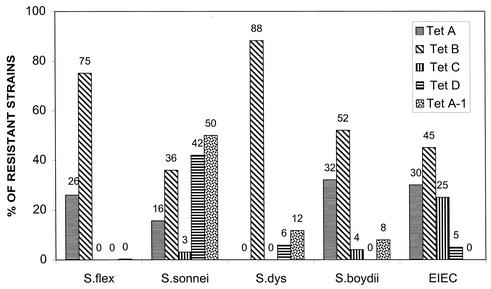

Distribution of Tet determinants in the 459 tetracycline-resistant isolates was first analyzed by species as shown in Fig. 2. Some percentages add up to more than 100% due to the presence of two determinants (see below). This is particularly true of S. sonnei in which 41% of the isolates contained both Tet A-1 and Tet D. These results represent Tet determinant distribution from all localities and time periods. Only Tet determinants of classes A to D and A-1 were found in the clinical isolates. It is apparent from these results that Tet B, which is the only efflux resistance determinant identified so far that confers resistance to minocycline as well as tetracycline, is the predominant tetracycline resistance determinant in shigellae and EIEC, with Tet A being the second most predominant. There was variation in the distribution of other determinants in the species. Only 8 of the 459 resistant strains (1.7%) contained the Tet C determinant, and 63% of these were EIEC strains, the only group with a notable percentage (25%) of Tet C. Both S. boydii (8 of 24 tetracycline-resistant strains) and EIEC (6 of 20 resistant strains) had a significant percentage of Tet A. In contrast, S. flexneri and S. dysenteriae were distinctive in the predominance (74 and 85%, respectively) of Tet B compared to the presence of Tet A (26 and 12%, respectively). S. sonnei had a unique distribution of tetracycline determinants, with Tet A-1 and Tet D being the predominant determinants. However, there is a locality difference in Tet distribution in S. sonnei as is shown in Table 3. When the determinants of S. sonnei from Thailand and Vietnam were compared, it was apparent that although Tet B was predominant in S. sonnei strains from Vietnam, Tet D and Tet A-1 were predominant in the specimens isolated from Thailand, and these determinants were found together in 93% of these isolates.

FIG. 2.

Distribution of tetracycline resistance determinants by species. The percentages of tetracycline resistance determinants Tet A to D and Tet A-1 determinants are shown as distributed by species. Percentages of each determinant are indicated for each species

TABLE 3.

Comparison of Tet determinant distribution in S. flexneri strains and S. sonnei strains from different geographical locations

| Species | Serotype | Location | No. of Tetr strains (% of total) | No. of strains positive for Tet determinant(s)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | A−1 | B | C | D | A−1 + D | A + B | ||||

| S. sonnei | Thailand | 27 (79) | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 0 | |

| Vietnam | 27 (69) | 4 | 1 | 15 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 4 | ||

| S. flexneri | Thailand | 111 (93) | 40 | 0 | 70 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| 2 | 43 (100) | 0 | 0 | 42 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 6 | 22 (92) | 0 | 0 | 22 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| X | 35 (100) | 35 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Vietnam | 146 (88) | 33 | 0 | 111 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | ||

| Not typed | 65 (93) | 9 | 0 | 55 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 1 | 21 (100) | 5 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 2 | 12 (100) | 0 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 6 | 22 (96) | 0 | 0 | 22 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Y | 12 (71) | 10 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Bangladesh | 18 (58) | 4 | 0 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 2 | 8 (47) | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 3 | 7 (100) | 2 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Egypt | 13 (57) | 0 | 1 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 2 | 5 (33) | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

Serotype differences in Tet distribution were also found within a species. In Table 3, the distributions of Tet determinants in S. flexneri strains and in the predominant S. flexneri serotypes in four countries were compared. All of the serotype 2 and serotype 6 strains from all locations contained only Tet B, except for one serotype 2 strain that had both Tet A and Tet B. In contrast, 100% of the serotype X strains from Thailand and 83% of the serotype Y strains from Vietnam contained Tet A. Also notable was the low percentage of tetracycline resistance in S. flexneri, particularly in serotype 2 in Bangladesh and Egypt.

Strains with two tetracycline resistance determinants.

Most Shigella strains contained only one Tet determinant. However, 9 of the 459 strains (2%) were positive for both Tet A and Tet B. Seven of these strains (five S. sonnei strains and two S. flexneri strains) were from Vietnam. One EIEC strain from Thailand had both Tet A and Tet D. The most significant numbers of strains with two determinants were the 25 S. sonnei strains and one S. dysenteriae strain from Thailand as well as one S. dysenteriae strain from Somalia that were positive for both Tet A-1 and Tet D. To confirm that these clinical isolates contained both determinants, the Tet D determinants from nine different isolates were sequenced, and the sequences were found to be identical to the GenBank entries for Tet D (L06798 and X65876). The Tet D determinant in these isolates was difficult to detect after subculture of the isolates. Whether this is due to instability of a plasmid or genetic element containing the gene or to masking of the gene by another determinant (Tet A or Tet A-1) is not known. Sequencing of Tet A-1 from three different isolates containing both genes also confirmed its presence. The presence of Tet A-1 was also confirmed using the Tet AF primer with Tet AR2 and Tet AR3 as shown in Fig. 1C. Since there was one EIEC strain that contained Tet D and the Tn1721-like Tet A determinant and eight strains from various localities that contained only Tet A-1, the Tet D determinant is likely located on a different genetic element than either Tet A or Tet A-1.

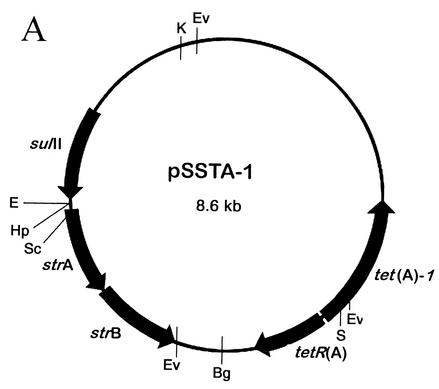

Characterization of pSSTA-1.

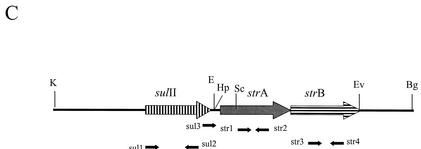

The plasmid containing the Tet A-1 determinant, designated pSSTA-1, was isolated from S. sonnei strain SPH-1482 from Thailand and characterized. The restriction map of the 8.6-kb plasmid is shown in Fig. 3A. The Tet A-1 determinant was located on the 4.67-kb KpnI-BglII fragment. This entire fragment was cloned into pUC18 (pTA-1) and sequenced, revealing the variation in the last 28 nucleotides of the coding region of tet(A)-1 as well as in the 3′ flanking region. A GenBank search using the BLAST system (http://www3.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) revealed that this region was >99% homologous at the DNA level to portions of a cryptic plasmid from S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Choleraesuis (accession number AB076707). The probable recombination site is shown in Fig. 3B. Note that at this site, both tet(A) and the Salmonella sequence contain the sequence TTGGAG. The 307-bp region 3′ to the TTGGAG in tet(A)-1 is also homologous to part of a putative transposase found in an E. coli plasmid encoding florfenicol resistance (AF231986), a Vibrio cholerae antibiotic resistance cluster (AY034138), and the sequence 3′ to the strB gene in plasmid RSF1010 (M28829). The rest of the coding region of tet(A)-1 and the sequence of tetR(A) located on pSSTA-1 are >99% homologous to the Tet A sequence found in Tn1721. pSSTA-1 also conferred resistance to streptomycin and trimethoprim (a sulfonamide), while pTA-1 only conferred tetracycline resistance, indicating that the other resistance genes were located on the 3.9-kb KpnI-BglII fragment. This fragment was cloned into pUC18 (pSTSU), mapped by restriction endonuclease analysis, and tested with primers specific for sulfonamide and streptomycin resistance genes to identify the other resistance genes found on pSSTA-1 (Materials and Methods). PCR products were obtained with sul1 and sul2, str1 and str2, str3 and str4, str1 and str4, sul3 and str2, and sul3 and str4, indicating that pSSTA-1 also contains sulII, strA, and strB. The genetic organization of this region is shown in Fig. 3C. This region is identical in organization to that found in plasmid RSF1010 (M28829), a broad-host-range plasmid found in many gram-negative enteric bacteria (28).

FIG. 3.

Characterization of pSSTA-1, the 8.6-kb plasmid containing Tet A-1. (A) Restriction map of pSSTA-1. Restriction endonucleases are abbreviated as follows: Bg, BglII; E, EcoRI; Ev, EcoRV; Hp, HpaI; K, KpnI; S, SalI; Sc, SacI. Positions of the sulII, strA, and strB genes and the tetR(A) and tet(A)-1 genes are indicated. (B) Schematic presentation of the 4.67-kb KpnI-BglII fragment containing Tet A-1. This entire fragment was sequenced. The positions of genes tetR(A) and tet(A)-1 and the likely site of recombination with the tet(A) gene present in Tn1721 and the Salmonella cryptic plasmid are shown. Amino acids for Tet(A) and Tet(A)-1 in the recombination region are given. The six homologous nucleotides found in tet(A), tet(A)-1, and the Salmonella plasmid are underlined. (C) Schematic presentation of the 3.9-kb KpnI-BglII fragment containing the streptomycin and sulfonamide resistance genes. Locations of primers specific for sulII, strA, and strB used to identify the presence of these genes and map the resistance region are shown. The genetic organization of this region is identical to that of broad-host-range plasmid RSF1010.

Epidemiology of strains and dissemination of pSSTA-1.

The results of identification of serotypes, Tet determinants, and antibiotic resistance profiles of these tetracycline-resistant isolates were used to examine mechanisms of dissemination of resistance determinants among strains and species. Examples of both clonal spread and horizontal transmission of antibiotic resistance were found. One example of clonal spread is found in the 35 S. flexneri X strains isolated from Thailand from 1992 to 1996 which all contain Tet A. S. flexneri X is not a common serotype, usually only found in a few percent of isolates from an area. Thus, the finding that these strains all contained Tet A and showed only two resistance profiles (data not shown) suggests that the serotype X strains are clonally related. The use of Tet A-1 and pSSTA-1 as epidemiological markers is shown in Table 4. Ninety-three percent of the S. sonnei strains from Thailand contained both Tet A-1 and Tet D, and 96% of these had the same resistance profile (data not shown), indicating that these isolates were likely clonal derivatives. The majority of strains containing Tet A-1 were S. sonnei from Thailand. The other strains that contained Tet A-1 were of various serogroups and came from different geographical localities (Table 4), suggesting the horizontal transmission of this resistance determinant among species. To confirm that the Tet A-1 determinant on the pSSTA-1 plasmid has been transferred between species, plasmid DNA was isolated from a diverse group of seven other strains that had been found to harbor Tet A-1 by PCR analysis. Plasmid DNA isolated from these strains was characterized by restriction mapping using restriction endonucleases shown in Fig. 3A and by PCR analysis (data not shown). The 8.6-kb plasmid from these strains was found to be identical in all seven strains to pSSTA-1. Lysates from eight additional strains containing Tet A-1 were also analyzed by PCR and found to contain the same 3′ flanking region, strA, strB, and sulII in the same genetic organization as pSSTA-1 (data not shown). Taken together, these data suggest that pSSTA-1-like plasmids were found at least as early as 1983 and have been disseminated in Shigella by clonal spread and by horizontal transmission to other species.

TABLE 4.

Strains containing Tet A-1 and probable mode of transmission

| Species | Source | Yr | No. of strains | Tet determinant(s) | Transmission |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. sonnei | Thailand | 1996-1998 | 25 | Tet A-1, Tet D | Clonal |

| S. dysenteriae serotype 1 | Thailand | 1996-1998 | 1 | Tet A-1, Tet D | Horizontal |

| S. dysenteriae serotype 1 | Somalia | 1993 | 1 | Tet A-1, Tet D | Horizontal |

| S. sonnei | Vietnam | 1999 | 1 | Tet A-1, Tet D | Clonal |

| S. sonnei | Thailand | 1996-1998 | 2 | Tet A-1 | Clonal |

| S. sonnei | Egypt | 1999 | 4 | Tet A-1 | Clonal |

| S. flexneri NTa | Egypt | 1999 | 1 | Tet A-1 | Horizontal |

| S. dysenteriae serotype 1 | Vietnam | 1998 | 2 | Tet A-1 | Horizontal |

| S. boydii | Vietnam | 1999 | 1 | Tet A-1 | Horizontal |

| S. sonnei | Vietnam | 1997 | 1 | Tet A-1 | Clonal |

| S. boydii | Bangladesh | 1999 | 1 | Tet A-1 | Horizontal |

| S. sonnei | Somalia | 1983 | 1 | Tet A-1 | Unknown |

NT, not typeable using S. flexneri serotype-specific antisera.

DISCUSSION

The only previous study on the distribution of tetracycline resistance determinants in Shigella spp. was a 1986 study of 53 non-lactose-fermenting coliforms (25 S. sonnei isolates, 8 S. flexneri isolates, and 20 Salmonella sp. isolates) isolated in Mexico City, Mexico, in 1978 and 1979 (22). In that study, Tet B was the predominant determinant for S. flexneri and Salmonella spp. Tet A and Tet C also occurred in S. flexneri, but less frequently (25 and 12.5%, respectively). However, 72% of the S. sonnei isolates had Tet C, 24% had Tet B, and 8% had Tet D. Only a small percentage of cases had two determinants except for S. flexneri, in which 25% of the eight strains had both Tet A and Tet B. However, this study was carried out 20 years ago with only 33 Shigella isolates from one geographical location and was done when antibiotic resistance was increasing rapidly in enteric bacteria. A more comprehensive study of the distribution of Tet determinants in the Shigella genus was obviously needed.

The study reported here examined the distribution of tetracycline determinants in 459 tetracycline-resistant clinical isolates of all four species of shigellae and EIEC from several different geographical locations and from countries in differing stages of development. Using primers specific for Tet A to E, G, and H in PCR analysis, it was established that Tet B was the predominant tetracycline resistance determinant in shigellae in all serogroups examined in this study and that only Tet determinants A, B, C, and D were represented in the 459 strains. Although Tet B was found to be the predominant determinant in the Shigella genus in both this study and the 1986 report, the results of this study differed from those of the 1986 work in the species distribution of the Tet determinants. For example, only 2 of the 64 S. sonnei isolates and none of the S. flexneri isolates contained Tet C, in contrast to the results of the earlier study. In the present study, only EIEC had a significant percentage of Tet C. Because of the large number of isolates from different locations in this study, it was possible to note both species and locality differences in tetracycline resistance distribution. This was particularly apparent in the difference in Tet determinant distribution in the S. sonnei isolates from Thailand and Vietnam. As was found in previous studies, there were very few cases where two resistance genes were found in one strain (8.2% of the strains examined) except for the Thailand S. sonnei strains. This may be the result of incompatibility of different resistance plasmids, as has been mentioned previously (6, 14).

This study demonstrated that both clonal spread and horizontal transmission have occurred in the dissemination of Tet determinants in shigellae. Clonal spread was most evident in the S. sonnei strains from Thailand, where all of the isolates either contained Tet A-1 and Tet D or Tet A-1 alone, and in the S. flexneri X strains from Thailand. Since S. sonnei has only one serotype, the identification of distinguishing epidemiological markers such as Tet A-1 is helpful in tracing clonal relationships. The presence of Tet A-1 and pSSTA-1 proved to be useful epidemiological markers for following transmission of resistance determinants and establishing horizontal transfer between species. Tet A-1 was found in a variety of serogroups from different geographical locations, suggesting the occurrence of horizontal transfer of this allele between species. PCR analysis and/or restriction analysis was used to identify the presence of pSSTA-1 in 15 other strains containing Tet A-1, thus making it possible to track the transmission of Tet A-1 and the transfer of the plasmid among different species and to determine that pSSTA-1-like plasmids were found in Shigella at least as early as 1983. However, from these results, it cannot be determined whether Tet A-1 and pSTA-1 originated in Shigella or in another genera of the Enterobacteriaceae.

The homology of pSSTA-1 to regions of the Salmonella cryptic plasmid including a portion of a putative transposase 3′ to the probable site of recombination indicates that an illegitimate recombination may have occurred to produce the Tet A-1 determinant. A recent publication (9) found that integration sites of foreign DNA into the genome of Acinetobacter species contained short stretches of sequence identity (3 to 8 bp) between donor and recipient DNA, indicating that illegitimate recombination is facilitated when homologous DNA is present. There are six homologous nucleotides (TTGGAG) at the likely site of recombination between Tet A from Tn1721 and the Salmonella cryptic plasmid. These same six nucleotides are also found after the strB gene and 5′ to the 307-bp putative transposase in RSF1010, suggesting that other recombinations may have occurred in the origin of pSSTA-1 to form the sulII-strA-strB region. Although the exact origin of pSSTA-1 is not known, the presence of a Salmonella cryptic plasmid in Shigella species demonstrates plasmid transfer between genera.

The four countries in this study with more than 35 isolates of various serogroups have differences in degree of development. Thailand is relatively developed and urban, while rural Bangladesh is considered a least-developed country by the United Nations. Vietnam and Egypt are intermediate between these two countries. In more-developed countries, S. sonnei is more prevalent and clonal spread of infection is the normal method of transmission (15). Certainly this was true in Thailand, where it was apparent from this study that 93% of the tetracycline-resistant S. sonnei strains were clonally related. In Bangladesh, no S. sonnei strains were isolated. In Vietnam, there were 27 S. sonnei tetracycline-resistant strains compared to 146 tetracycline-resistant S. flexneri strains. The distribution of Tet determinants in S. sonnei in Vietnam was quite different from that in Thailand, and there was only a limited suggestion of clonality. In Egypt, there were only four resistant S. sonnei strains compared to 13 resistant S. flexneri strains, but they all contained Tet A-1 and appeared to be clonally related. These observations suggest that the epidemiological monitoring of antibiotic resistance spread may lend new insights into the mechanisms of dissemination of these determinants that may be related to environmental factors such as the development of the region.

In summary, this work presents the first comprehensive study of Tet determinant distribution in the genus Shigella, using a large number of clinical isolates from a variety of geographical locations. The use of Tet determinant identification in epidemiological analysis of clonal spread and resistance transmission among species and strains was demonstrated. In addition, the usefulness in epidemiological studies of the identification of specific markers such as the Tet A-1 determinant and pSSTA-1 was shown. The impact that environment and regional development have on movement of these determinants will be the subject of future investigations.

Acknowledgments

We thank Phung Dac Cam and staff of the National Institute of Hygiene and Epidemiology in Hanoi, Vietnam, and Apichai Arijan, Peter Echeverria, and staff of the Armed Forces Institute of Medical Sciences in Bangkok, Thailand, for the strains and for providing serotype and resistance data for these strains. We thank Leonard Peruski, Jr., for the strains from Egypt and the serotype and resistance data for these strains. We also thank Marilyn Roherts for the control strains for Tet D, Tet E, Tet G, and Tet H. We also thank Wei Fan and Ying Liu for sequencing of tet genes and Robert Gunderson for excellent technical assistance.

Opinions, interpretations, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the authors and are not necessarily endorsed by the U.S. Army.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aarts, H. J., K. S. Boumedine, X. Nesme, and A. Cloeckaert. 2001. Molecular tools for the characterisation of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Vet. Res. 32:363-380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amabile-Cuevas, C. F., and M. E. Chicurel. 1992. Bacterial plasmids and gene flux. Cell 70:189-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersen, S. R., and R.-A. Sandaa. 1994. Distribution of tetracycline resistance determinants among gram-negative bacteria isolated from polluted and unpolluted marine sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:908-912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bauer, A. W., W. M. Kirby, J. C. Sherris, and M. Turck. 1966. Antibiotic susceptibility testing by a standardized single disc method. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 45:638-645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bergeron, M. G., and M. Ouellette. 1998. Preventing antibiotic resistance through rapid genotypic identification of bacteria and of their antibiotic resistance genes in the clinical microbiology laboratory. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:2169-2172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chopra, I., and M. Roberts. 2001. Tetracycline antibiotics: mode of action, applications, molecular biology, and epidemiology of bacterial resistance. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 65:232-260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Courvalin, P. 1991. Genotypic approach to the study of bacterial resistance to antibiotics. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 35:1019-1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Courvalin, P. 1994. Transfer of antibiotic resistance genes between gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:1447-1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Vries, J., and W. Wackernagel. 2002. Integration of foreign DNA during natural transformation of Acinetobacter sp. by homology-facilitated illegitimate recombination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:2094-2099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guardabassi, L., L. Dijkshoorn, J. M. Collard, J. E. Olsen, and A. Dalsgaard. 2000. Distribution and in-vitro transfer of tetracycline resistance determinants in clinical and aquatic Acinetobacter strains. J. Med. Microbiol. 49:929-936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hansen, L. M., L. M. McMurray, S. B. Levy, and D. C. Hirsh. 1993. A new tetracycline resistance determinant, Tet H, from Pasteurella multocida specifying active efflux of tetracycline. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37:2699-2705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoge, C. W., J. M. Gambel, A. Srijan, C. Pitarangsi, and P. Echeverria. 1998. Trends in antibiotic resistance among diarrheal pathogens isolated in Thailand over 15 years. Clin. Infect. Dis. 26:341-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Isenbarger, D. W., C. W. Hoge, A. Srijan, C. Pitarangsi, N. Vitayasai, L. Bodhidatta, K. W. Hickey, and P. D. Cam. 2002. Comparative antibiotic resistance in diarrheal pathogens from Vietnam and Thailand, 1996-1999. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 8:175-180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones, C. S., D. J. Osborne, and J. Stanley. 1992. Enterobacterial tetracycline resistance in relation to plasmid incompatibility. Mol. Cell. Probes 6:313-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kotloff, L. L., J. P. Winickoff, B. Ivanoff, J. D. Clemens, D. L. Swerdlow, P. J. Sansonetti, G. K. Adak, and M. M. Levine. 1999. Global burden of Shigella infections: implications for vaccine development and implementation of control strategies. Bull. W. H. O. 77:651-666. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee, C., B. E. Langlois, and K. A. Dawson. 1993. Detection of tetracycline resistance determinants in pig isolates from three herds with different histories of antimicrobial exposure. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:1467-1472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levy, S. B., L. M. McMurry, T. M. Barbosa, V. Burdett, P. Courvalin, W. Hillen, M. C. Roberts, J. I. Rood, and D. E. Taylor. 1999. Nomenclature for new tetracycline resistance determinants. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:1523-1524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levy, S. B., L. M. McMurray, V. Burdett, P. Courvalin, W. Hillen, M. C. Roberts, and D. E. Taylor. 1989. Nomenclature for tetracycline resistance determinants. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 33:1374.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lima, A. A., N. L. Lima, M. C. Pinho, E. A. Barros, Jr., M. J. Teixeira, M. C. Martins, and R. L. Guerrant. 1995. High frequency of strains multiply resistant to ampicillin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, streptomycin, chloramphenicol, and tetracycline isolated from patients with shigellosis in northeastern Brazil during the period 1988 to 1993. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:256-259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mahoney, F. J., T. A. Farley, D. F. Burbank, N. H. Leslie, and L. M. McFarland. 1993. Evaluation of an intervention program for the control of an outbreak of shigellosis among institutionalized persons. J. Infect. Dis. 168:1177-1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marshall, B., C. Tachibana, and S. B. Levy. 1983. Frequency of tetracycline resistance determinant classes among lactose-fermenting coliforms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 24:835-840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martinez-Salazar, J. M., G. Alvarez, and M. C. Gomez-Eichelmann. 1986. Frequency of four classes of tetracycline resistance determinants in Salmonella and Shigella sp. clinical isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 30:630-631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mates, A., D. Eyny, and S. Philo. 2000. Antimicrobial resistance trends in Shigella serotypes isolated in Israel, 1990-1995. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 19:108-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ng, L.-K., M. Mulvey, I. Martin, G. Peters, and W. Johnson. 1999. Genetic characterization of antimicrobial resistance in Canadian isolates of Salmonella serovar Typhimurium DT104. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:3018-3021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosser, S., and H. Young. 1999. Identification and characterization of class 1 integrons in bacteria from an aquatic environment. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 44:11-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sack, R. B., M. Rahman, M. Yunus, and E. H., Khan. 1997. Antimicrobial resistance in organisms causing diarrheal disease. Clin. Infect. Dis. 24(Suppl. 1):D102-D105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schnabel, E., and A. L. Jones. 1999. Distribution of tetracycline resistance genes and transposons among phylloplane bacteria in Michigan apple orchards. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:4898-4907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scholtz, P., V. Haring, B. Wittmann-Liebold, K. Ashman, M. Bagdasarian, and E. Scherzinger. 1989. Complete nucleotide sequence and gene organization of the broad-host-range plasmid RSF1010. Gene 75:271-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sharp, T. W., S. A. Thornton, M. R. Wallace, R. F. Defraites, J. L. Sanchez, R. A. Batchelor, P. J. Rozmajzll, R. K. Hanson, P. Echeverria, A. Z. Kapikian, et al. 1995. Diarrheal disease among military personnel during Operation Restore Hope, Somalia, 1992-1995. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 52:188-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stewart, G. L., and C. D. Sinigalliano. 1990. Detection of horizontal gene transfer natural transformation in native and introduced species of bacteria in marine and synthetic sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56:1818-1824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tauxe, R. V., N. D. Puhr, J. G. Wells, N. Hargrett-Bean, and P. A. Blake. 1990. Antimicrobial resistance of Shigella isolates in the USA: the importance of international travelers. J. Infect. Dis. 162:1107-1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]