Abstract

Unlike Shiga toxin 2 (stx2) genes, most nucleotide sequences of Shiga toxin 1 (stx1) genes from Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC), Shigella dysenteriae, and several bacteriophages (H19B, 933J, and H30) are highly conserved. Consequently, there has been little incentive to investigate variants of stx1 among STEC isolates derived from human or animal sources. However stx1OX3, originally identified in an OX3:H8 isolate from a healthy sheep in Germany, differs from other stx1 subtypes by 43 nucleotides, resulting in changes to 12 amino acid residues, and has been renamed stx1c. In this study we describe the development of a PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) assay that distinguishes stx1c from other stx1 subtypes. The PCR-RFLP assay was used to study 378 stx1-containing STEC isolates. Of these, 207 were isolated from sheep, 104 from cattle, 45 from humans, 11 from meat, 5 from swine, 5 from unknown sources, and 1 from a cattle water trough. Three hundred fifty-five of the 378 isolates (93.9%) also possessed at least one other associated virulence gene (ehxA, eaeA, and/or stx2); the combination stx1, stx2, and ehxA was the most common (175 of 355 [49.3%]), and 90 of 355 (25.4%) isolates possessed eaeA. One hundred thirty-six of 207 (65.7%) ovine isolates possessed stx1c alone and belonged to 41 serotypes. Seventy-one of 136 (52.2%) comprised the common ovine serotypes O5:H−, O128:H2, and O123:H−. Fifty-two of 207 isolates (25.1%) possessed an stx1 subtype; 27 (51.9%) of these belonged to serotype O91:H−. Nineteen of 207 isolates (9.2%) contained both stx1c and stx1 subtypes, and 14 belonged to serotype O75:H8. In marked contrast, 97 of 104 (93.3%) bovine isolates comprising 44 serotypes possessed an stx1 subtype, 6 isolates possessed stx1c, and the remaining isolate possessed both stx1c and stx1 subtypes. Ten of 11 (91%) isolates cultured from meat in New Zealand possessed stx1c (serotypes O5:H−, O75:H8/H40, O81:H26, O88:H25, O104:H−/H7, O123:H−/H10, and O128:H2); most of these serotypes are commonly recovered from the feces of healthy sheep. Serotypes containing stx1 recovered from cattle rarely were the same as those isolated from sheep. Although an stx1c subtype was never associated with the typical enterohemorrhagic E. coli serogroups O26, O103, O111, O113, and O157, 13 human isolates possessed stx1c. Of these, six isolates with serotype O128:H2 (from patients with diarrhea), four O5:H− isolates (from patients with hemolytic-uremic syndrome), and three isolates with serotypes O123:H− (diarrhea), OX3:H8 (hemolytic-uremic syndrome), and O81:H6 (unknown health status) represent serotypes that are commonly isolated from sheep.

Ruminants represent one of the largest reservoirs of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC), which is commonly excreted in the feces of meat-producing animals (3, 5, 6, 14, 22, 27, 29, 30, 50). More than 200 different serotypes of STEC have been described so far (13, 22, 28, 61), and more than 150 of these have been reported to have been recovered from humans with hemorrhagic colitis or hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS) (http://www.microbionet.com.au). However, a subset of STEC strains (e.g., those of serogroups O26, O103, O111, O113, and O157), often referred to as enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC), are more commonly associated with such serious afflictions and often possess associated virulence factors such as plasmid-encoded enterohemolysin and proteins (EaeA, Tir, and Esp) encoded by the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE) (10, 22, 47). Although genes such as saa (45), iha (55), ureC (23, 36), and efaI (39) have been found in association with the genomes of such STEC strains, further studies are needed to determine their role in pathogenesis. Furthermore, differences in levels of secreted LEE proteins among STEC serotypes may also affect virulence (32).

In marked contrast to the expression of stx2, expression of stx1 in E. coli is regulated by host-derived signals such as the availability of iron and body temperature (11). stx1 sequences derived from STEC O111:H− and O48:H21 strains and from three bacteriophages (H19B, 933J, and H30) have been reported to be very similar to the sequence derived from Shigella dysenteriae (43) and result in a limited number of amino acid substitutions. Unlike these common stx1 subtypes, stx1OX3 possesses 43 nucleotide mismatches compared to stx1933-J, resulting in 12 amino acid changes (43). Koch et al. (30) have examined the presence of stx1OX3 among 148 stx1-containing E. coli isolates derived from human and animal sources. The stx1OX3 gene was shown to be present in 38 of 48 (79.2%) sheep-derived STEC isolates belonging to serotypes O5:NM, O125:H−, O128:H2, O146:H21, and OX3:H8 but was not present in isolates with serotype O91:NM. These serotypes are commonly recovered from ovine but rarely from bovine sources (5-7, 14, 27, 31, 50). Koch et al., (30) also showed that stx1OX3-positive strains were recovered from humans with diarrhea and that a proportion of these isolates possessed serotypes commonly associated with STEC from ovine sources. These preliminary observations suggest that the association of the stx1OX3 gene with ovine STEC strains from other geographical locations requires further investigation.

Zhang et al. (63) investigated the presence of the atypical stx1OX3 variant among 212 STEC strains recovered from humans. These authors renamed stxOX3, designating it stx1c (63). Since stx1c has now been identified among serologically diverse STEC strains (30, 58, 63), we retained this nomenclature for our study. Zhang et al. (63) reported stx1c in 36 STEC strains, of which 23 concomitantly possessed stx2d, 12 possessed stx1c alone, and 1 possessed both stx1c and stx2. Of the 36 stx1c-positive strains, 19 were recovered from asymptomatic patients and 16 were derived from fecal samples of patients with uncomplicated diarrhea. Only a single stx1c-positive isolate was recovered from a patient with HUS. The 36 stx1c-positive isolates belonged to 15 serotypes, none of which included the major STEC serogroups (O26, O103, O111, O113, O145, and O157) (63). Several studies (19, 30, 50, 58, 63) suggest that sheep may be a natural reservoir of stx1c-positive STEC strains that enter the human food chain.

Shiga toxin genes (stx) are encoded in the genomes of lambdoid phages (51). Bacteriophage transmission represents the major vehicle in the spread of stx among serologically diverse populations of E. coli (30, 51) and contributes significantly to the emergence of new STEC clones (51). The location of stx downstream of phage lysis genes suggests that phage promoters (57, 59) control the expression of Shiga toxin. Bacteriophages survive better in water than their bacterial hosts and are reported to be more resistant to chlorination and pasteurization (34, 35). Monitoring stx subtypes within ruminant and environmental populations of STEC should lead to a better understanding of the movement of bacteriophage within these environments.

Shiga toxins play a major role in inducing vascular injury in the intestinal microcirculation and have been shown to directly affect the intestinal epithelium, although different responses have been reported for different hosts (reviewed in reference 40). More specifically, Shiga toxins perturb cytokine expression patterns as a consequence of their interaction with epithelial cells (1, 56, 62). Rabbit models have been used to demonstrate the ability of stx1-positive strains to induce more-severe diarrhea and mucosal injury (54), increased inflammatory changes, and elevated mucosal interleukin-1 activity (8) compared with those in rabbits infected with isogenic strains lacking stx1. The ability of purified stx1 to induce similar inflammatory responses when inoculated intragastrically into rabbits reinforces these observations (41). However, to our knowledge, the abilities of different Shiga toxin 1 subtypes to induce these physiological changes have not been addressed.

A recent report demonstrating that bovine crypt intestinal epithelium, lining the ileum and jejunum of the small intestine and the cecum and colon of the large intestine, expresses Gb3 receptors for verotoxin 1 (stx1) from E. coli O157:H7 has potentially profound implications for the role of Shiga toxin in the colonization of ruminant species by STEC (25). The hypothesis that Shiga toxin 1 may modulate the bovine immune response is supported by observations that this toxin (i) has been shown to inhibit the activation and proliferation of subpopulations of bovine lymphocytes (33), (ii) suppresses bovine leukemia virus-related spontaneous lymphocyte proliferation (18), and (iii) binds to submucosal lymphoid aggregates (25). Although STEC typically inhabits the gastrointestinal tracts of healthy meat-producing animals, certain subpopulations of STEC may also induce gastrointestinal disease in these animals (9, 60). Wieler et al. (60) showed that the majority of STEC isolates recovered from diarrheic calves concomitantly possessed eaeA and stx1, and they concluded that stx1-positive strains are more virulent for calves. To our knowledge, the presence of different stx1 subtypes among STEC isolates derived from cattle has not been intensively investigated.

Previously, we and others have shown that STEC strains that commonly inhabit the gastrointestinal tracts of healthy sheep and cattle represent serologically distinct populations (5-7, 14, 27, 58). Furthermore, it has also been demonstrated that STEC isolates with stx2 that are commonly recovered from sheep predominantly possess the stx2d subtype (46, 48, 50) whereas bovine stx2-containing STEC isolates typically possess stx2 and stx2vha/b subtypes (3; our unpublished data). We considered it important to subtype stx1 genes in a serologically diverse collection of STEC isolates derived predominantly from ruminants in Australia in order to determine if different stx1 subtypes also associate with particular hosts. In this study a PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) assay which differentiates stx1c from the common stx1-related sequences was developed. The assay was used to characterize 378 stx1-containing STEC isolates derived predominantly from ovine and bovine sources. We also examined stx1 subtypes in 45 human STEC strains derived mostly from patients with gastrointestinal and systemic diseases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

STEC isolates.

Three hundred seventy-eight stx1-containing STEC isolates were used in this study (Table 1); of these, 313 were derived from healthy meat-producing animals, 45 were of human origin, 11 were from a blind study of meat from New Zealand, 5 had unknown histories, 3 were individual isolates from bovines of unknown health status, and 1 was from a water source. Two hundred seven isolates were derived from ovine sources (203 animals) and were obtained from the Elizabeth Macarthur Agricultural Institute (EMAI), Camden, New South Wales, Australia. One hundred four isolates were of bovine origin (83 animals); of these, 99 were obtained from the EMAI and 5 were from the Microbiological Diagnostic Unit (MDU), Melbourne, Australia. The majority of these STEC isolates were collected from healthy sheep and cattle in eastern Australia (14, 27; our unpublished data). Five stx1-containing isolates from healthy pigs from the EMAI collection were also included. Thirty-seven stx1-containing human isolates were from the MDU, and eight isolates were from the National Reference Laboratory for Foodborne Diseases, Bern, Switzerland. The 37 human isolates from the MDU included 4 isolates (O81:H6, OR:H−, Ont:H−, and O26:H11) from New Zealand (from individuals of unknown health status), 3 O157:H7 isolates from the 1996 outbreak in Japan (kindly supplied by H. Watanabe), 2 O111:H− isolates from Italy (kindly provided by A. Caprioli), and a single O157:H7 isolate from the Jack-in-the-Box outbreak in the United States (Table 1). B. Bochner kindly supplied isolates from the United States. These isolates were cultured by previously published procedures (14).

TABLE 1.

Virulence factor profiles and stx1 subtypes among STEC isolates of animal and human origins

| Sourcea | Clinical conditionb | Serotype | No. of isolates | No. of animals or humans | Virulence factor profile

|

No. of isolates with stx1 subtype:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| stx1 | stx2 | eaeA | ehxA | stx1 | stx1c | stx1/stx1c | |||||

| Ovine | Healthy | O2:H29 | 1 | 1 | + | − | − | + | 1 | ||

| Bovine | Healthy | O3:H7 | 7 | 2 | + | + | − | + | 7 | ||

| Bovine | Healthy | O5:H− | 3 | 3 | + | + | − | + | 1 | 2 | |

| Bovine | Diagnostic | O5:H− | 5 | 1 | + | − | + | + | 5 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | O5:H− | 14 | 14 | + | + | − | + | 14 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | O5:H− | 7 | 6 | + | − | − | + | 7 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | O5:H− | 1 | 1 | + | + | − | − | 1 | ||

| Human/MDU | HUS | O5:H− | 1 | 1 | + | − | + | + | 1 | ||

| Human/MDU | HUS | O5:H− | 2 | 2 | + | − | − | + | 2 | ||

| Human/MDU | HUS | O5:H− | 1 | 1 | + | + | − | + | 1 | ||

| Meat/New Zealand | Unknown | O5:H− | 1 | 1 | + | + | − | + | 1 | ||

| Bovine | Healthy | O5:H7 | 3 | 3 | + | + | − | + | 3 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | O5:HR | 1 | 1 | + | + | + | + | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | O6:H− | 1 | 1 | + | + | − | + | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | O6:H− | 1 | 1 | + | − | − | + | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | O8:Hnt | 1 | 1 | + | + | − | + | 1 | ||

| Human/NRLFD | HUS | O8:H8 | 1 | 1 | + | − | − | − | 1 | ||

| Bovine | Healthy | O8:H16 | 1 | 1 | + | + | − | + | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | O21:H21 | 1 | 1 | + | + | − | + | 1 | ||

| Bovine | Healthy | O26:H− | 1 | 1 | + | − | + | + | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | O26:H− | 2 | 2 | + | − | + | + | 2 | ||

| Human/MDU | Diarrhea | O26:H− | 3 | 3 | + | − | + | + | 3 | ||

| Unknown/United States | Unknown | O26:H− | 1 | 1 | + | − | + | + | 1 | ||

| Bovine | Healthy | O26:H11 | 11 | 7 | + | − | + | + | 11 | ||

| Bovine | Healthy | O26:H11 | 1 | 1 | + | − | − | + | 1 | ||

| Bovine | Healthy | O26:H11 | 1 | 1 | + | − | − | − | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | O26:H11 | 4 | 4 | + | − | + | + | 4 | ||

| Human/MDU | Diarrhea | O26:H11 | 3 | 3 | + | − | + | − | 3 | ||

| Human/MDU | Diarrhea | O26:H11 | 6 | 5 | + | − | + | + | 6 | ||

| Human/NRLFD | Diarrhea | O26:H11 | 2 | 2 | + | − | + | + | 2 | ||

| Human/New Zealand | Unknown | O26:H11 | 1 | 1 | + | − | + | + | 1 | ||

| Bovine | Healthy | O28:H− | 1 | 1 | + | − | + | + | 1 | ||

| Bovine | Healthy | O32/83:H7 | 1 | 1 | + | − | − | − | 1 | ||

| Bovine | Healthy | O37:H10 | 1 | 1 | + | + | + | − | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | O55:H20 | 1 | 1 | + | + | + | + | 1 | ||

| Bovine | Healthy | O68:H− | 1 | 1 | + | − | − | + | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | O69:H8 | 1 | 1 | + | − | − | − | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | O75:H− | 1 | 1 | + | + | − | − | 1 | ||

| Bovine | Healthy | O75:H1 | 1 | 1 | + | − | − | + | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | O75:H8 | 3 | 3 | + | + | − | − | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Ovine | Healthy | O75:H8 | 1 | 1 | + | − | − | − | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | O75:H8 | 16 | 16 | + | + | − | + | 1 | 2 | 13 |

| Ovine | Healthy | O75:H8 | 1 | 1 | + | − | − | + | 1 | ||

| Meat/New Zealand | Unknown | O75:H8 | 1 | 1 | + | + | − | + | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | O75:H40 | 1 | 1 | + | − | − | + | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | O75:H40 | 1 | 1 | + | + | − | + | 1 | ||

| Meat/New Zealand | Unknown | O75:H40 | 1 | 1 | + | + | − | + | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | O77:H4 | 1 | 1 | + | − | − | + | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | O77:H− | 1 | 1 | + | − | − | + | 1 | ||

| Human/New Zealand | Unknown | O81:H6 | 1 | 1 | + | − | − | + | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | O81:H26 | 1 | 1 | + | − | − | + | 1 | ||

| Meat/New Zealand | Unknown | O81:H26 | 1 | 1 | + | − | − | + | 1 | ||

| Bovine | Healthy | O81:H31 | 1 | 1 | + | − | − | + | 1 | ||

| Bovine | Healthy | O82:H40 | 2 | 2 | + | + | − | + | 2 | ||

| Bovine | Healthy | O82:H8 | 6 | 6 | + | + | − | + | 6 | ||

| Bovine | Healthy | O84:H− | 1 | 1 | + | − | + | + | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | O84:H− | 1 | 1 | + | − | + | + | 1 | ||

| Bovine | Healthy | O84:H2 | 1 | 1 | + | − | + | + | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | O88:H8 | 1 | 1 | + | + | + | − | 1 | ||

| Meat/New Zealand | Unknown | O88:H25 | 1 | 1 | + | − | − | − | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | O91:H− | 21 | 20 | + | + | − | + | 18 | 3 | |

| Ovine | Healthy | O91:H− | 6 | 6 | + | − | − | + | 4 | 2 | |

| Ovine | Healthy | O91:H− | 5 | 5 | + | + | − | − | 5 | ||

| Human/MDU | Healthy | O91:H− | 2 | 2 | + | + | − | − | 2 | ||

| Meat/New Zealand | Unknown | O91:H− | 1 | 1 | + | + | − | + | 1 | ||

| Bovine/Hong Kong | Unknown | O91:H14 | 1 | 1 | + | + | − | + | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Diagnostic | O103:H2 | 1 | 1 | + | − | + | + | 1 | ||

| Human/MDU | Diarrhea | O103:H2 | 1 | 1 | + | − | + | + | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | O103:H38 | 1 | 1 | + | + | − | + | 1 | ||

| Meat/New Zealand | Unknown | O104:H7 | 1 | 1 | + | − | − | − | 1 | ||

| Meat/New Zealand | Unknown | O104:H− | 1 | 1 | + | − | − | − | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | O106:H18 | 1 | 1 | + | + | − | + | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | O106:HR | 1 | 1 | + | − | + | − | 1 | ||

| Bovine | Healthy | O108:H7 | 3 | 3 | + | + | − | + | 3 | ||

| Bovine | Healthy | O108:H7 | 1 | 1 | + | − | − | − | 1 | ||

| Bovine | Healthy | O110:H40 | 1 | 1 | + | + | − | + | 1 | ||

| Bovine | Healthy | O111:H− | 2 | 2 | + | + | + | + | 2 | ||

| Human/Italy | Unknown | O111:H− | 1 | 1 | + | − | + | − | 1 | ||

| Human/Italy | Unknown | O111:H− | 1 | 1 | + | + | + | − | 1 | ||

| Unknown/Canada | Unknown | O111:H− | 1 | 1 | + | − | + | − | 1 | ||

| Unknown/United States | Unknown | O111:H− | 1 | 1 | + | − | + | − | 1 | ||

| Unknown/Germany | Unknown | O111:H− | 1 | 1 | + | − | + | − | 1 | ||

| Bovine | Healthy | O111:H8 | 2 | 1 | + | + | + | + | 2 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | O112ab:H2 | 2 | 2 | + | + | − | − | 2 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | O112ab:H2 | 1 | 1 | + | − | − | − | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | O112ab:H2 | 1 | 1 | + | + | + | + | 1 | ||

| Bovine | Healthy | O113:H4 | 1 | 1 | + | + | − | − | 1 | ||

| Bovine/Canada | Unknown | O113:H4 | 1 | 1 | + | + | − | − | 1 | ||

| Bovine | Unknown | O113:H21 | 1 | 1 | + | − | − | + | 1 | ||

| Bovine | Unknown | O113:H21 | 1 | 1 | + | + | − | − | 1 | ||

| Human/NRLFD | Diarrhea | O117:H7 | 2 | 2 | + | − | − | − | 2 | ||

| Bovine | Healthy | O117:H21 | 1 | 1 | + | − | − | − | 1 | ||

| Human/NRLFD | Diarrhea | O118:H16 | 1 | 1 | + | − | + | + | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | O121:H2 | 1 | 1 | + | + | − | + | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | O123:H− | 1 | 1 | + | − | − | + | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | O123:H− | 1 | 1 | + | + | + | + | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | O123:H− | 19 | 19 | + | + | − | + | 19 | ||

| Human/NRLFD | Diarrhea | O123:H− | 1 | 1 | + | + | − | + | 1 | ||

| Meat/New Zealand | Unknown | O123:H− | 1 | 1 | + | + | − | + | 1 | ||

| Meat/New Zealand | Unknown | O123:H10 | 1 | 1 | + | + | − | + | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | O123:H11 | 1 | 1 | + | − | − | + | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | O128:H2 | 19 | 19 | + | + | − | + | 19 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | O128:H2 | 5 | 5 | + | − | − | + | 5 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | O128:H2 | 2 | 2 | + | + | − | − | 2 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | O128:H2 | 1 | 1 | + | − | − | − | 1 | ||

| Human/MDU | Diarrhea | O128:H2 | 4 | 4 | + | + | − | + | 4 | ||

| Human/MDU | Diarrhea | O128:H2 | 2 | 2 | + | + | − | − | 2 | ||

| Meat/New Zealand | Unknown | O128:H2 | 1 | 1 | + | + | − | + | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | O128:H-/H2 | 1 | 1 | + | − | − | − | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | O128:H8/H2 | 1 | 1 | + | + | − | + | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | O128:Hnt | 1 | 1 | + | + | − | + | 1 | ||

| Bovine | Healthy | O130:H11 | 2 | 2 | + | + | − | + | 2 | ||

| Bovine | Healthy | O130:H11 | 1 | 1 | + | + | − | − | 1 | ||

| Bovine | Healthy | O130:H38 | 2 | 2 | + | + | − | + | 2 | ||

| Bovine | Healthy | O149:H19 | 1 | 1 | + | + | − | − | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | O152:H21 | 1 | 1 | + | + | − | + | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | O153:H− | 1 | 1 | + | − | − | − | 1 | ||

| Bovine | Healthy | O153:H8 | 1 | 1 | + | + | − | + | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | O153:H8 | 1 | 1 | + | + | − | − | 1 | ||

| Bovine | Healthy | O153:H21 | 1 | 1 | + | − | − | − | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | O153:H25 | 3 | 3 | + | − | − | + | 3 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | O153:H25 | 1 | 1 | + | + | − | + | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | O153:H25 | 1 | 1 | + | − | − | − | 1 | ||

| Bovine | Healthy | O153:HR | 1 | 1 | + | + | − | + | 1 | ||

| Water | N/A | O154:H− | 1 | 1 | + | + | + | + | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | O154:HR | 1 | 1 | + | − | − | + | 1 | ||

| Bovine | Healthy | O157:H− | 1 | 1 | + | + | − | − | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | O157:H− | 2 | 2 | + | + | + | + | 2 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | O157:H− | 2 | 2 | + | + | − | + | 2 | ||

| Porcine | Healthy | O157:H− | 5 | 2 | + | − | + | + | 5 | ||

| Bovine | Healthy | O157:H7 | 1 | 1 | + | + | + | + | 1 | ||

| Bovine/Finland | Unknown | O157:H7 | 1 | 1 | + | + | + | + | 1 | ||

| Human/Japan | Unknown | O157:H7 | 1 | 1 | + | + | + | + | 1 | ||

| Human/Japan | Unknown | O157:H7 | 1 | 1 | + | + | + | + | 1 | ||

| Human/United States | Unknown | O157:H7 | 1 | 1 | + | − | + | + | 1 | ||

| Unknown/United States | Unknown | O157:H7 | 1 | 1 | + | + | + | − | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | O157:H21 | 1 | 1 | + | + | + | + | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | O158:HR | 1 | 1 | + | − | + | + | 1 | ||

| Bovine | Healthy | O163:H− | 1 | 1 | + | + | − | + | 1 | ||

| Bovine | Healthy | O163:H19 | 1 | 1 | + | + | − | + | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | O163:H19 | 1 | 1 | + | − | − | − | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | O168:H21 | 1 | 1 | + | − | − | − | 1 | ||

| Bovine | Healthy | Ont:H1 | 2 | 2 | + | + | − | + | 2 | ||

| Bovine | Healthy | Ont:H2 | 2 | 1 | + | + | − | + | 2 | ||

| Bovine | Healthy | Ont:H4 | 1 | 1 | + | − | − | + | 1 | ||

| Bovine | Healthy | Ont:H8 | 1 | 1 | + | + | − | + | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | Ont:H8 | 1 | 1 | + | + | + | − | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | Ont(A):H8 | 1 | 1 | + | + | − | − | 1 | ||

| Bovine | Healthy | Ont:H10 | 1 | 1 | + | − | − | − | 1 | ||

| Bovine | Healthy | Ont:H11 | 6 | 2 | + | + | − | + | 6 | ||

| Bovine | Healthy | Ont:H16 | 2 | 1 | + | + | − | + | 2 | ||

| Bovine | Healthy | Ont:H19 | 1 | 1 | + | + | − | + | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | Ont:H19 | 1 | 1 | + | + | − | − | 1 | ||

| Bovine | Healthy | Ont:H21 | 2 | 2 | + | + | − | + | 2 | ||

| Bovine | Healthy | Ont:H30 | 1 | 1 | + | + | − | + | 1 | ||

| Bovine | Healthy | Ont:H41 | 1 | 1 | + | − | + | + | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | Ont:H49 | 1 | 1 | + | + | + | − | 1 | ||

| Bovine | Healthy | Ont:H− | 2 | 1 | + | − | + | + | 2 | ||

| Bovine | Healthy | Ont:H− | 1 | 1 | + | + | − | + | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | Ont:H− | 1 | 1 | + | − | − | − | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | Ont:H− | 2 | 2 | + | + | − | − | 2 | ||

| Human/MDU | Unknown | Ont:H− | 1 | 1 | + | − | + | + | 1 | ||

| Human/New Zealand | Unknown | Ont:H− | 1 | 1 | + | − | + | + | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | Ont(A):H− | 1 | 1 | + | − | − | + | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | Ont:HR | 9 | 7 | + | − | − | + | 9 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | Ont:Hnt | 1 | 1 | + | + | − | − | 1 | ||

| Human/MDU | Healthy | Ont:Hnt | 1 | 1 | + | − | + | + | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | OR:H2 | 2 | 2 | + | + | − | + | 2 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | OR:H2 | 1 | 1 | + | − | − | + | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | OR:H4 | 2 | 2 | + | + | − | + | 2 | ||

| Human/Japan | Unknown | OR:H7 | 1 | 1 | + | − | + | + | 1 | ||

| Bovine | Healthy | OR:H31 | 1 | 1 | + | + | + | + | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | OR:HR | 1 | 1 | + | − | − | + | 1 | ||

| Bovine | Healthy | OR:H− | 1 | 1 | + | − | + | + | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | OR:H− | 2 | 2 | + | + | − | + | 2 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | OR:H− | 1 | 1 | + | + | − | − | 1 | ||

| Human/New Zealand | Unknown | OR:H− | 1 | 1 | + | − | − | + | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | OX3:H2 | 1 | 1 | + | − | − | − | 1 | ||

| Bovine | Healthy | OX3:H8 | 1 | 1 | + | + | − | + | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | OX3:H8 | 1 | 1 | + | + | − | − | 1 | ||

| Human/NRLFD | HUS | OX3:H8 | 1 | 1 | + | + | − | − | 1 | ||

| Ovine | Healthy | OX3:HR | 3 | 3 | + | − | − | + | 3 | ||

NRLFD, National Reference Laboratory for Foodborne Diseases.

N/A, not applicable.

Multiplex PCR analysis of STEC isolates.

All isolates were prepared and subjected to multiplex PCR for detection of STEC virulence factors stx1, stx2, ehxA, and eaeA as described previously (44) with the following modification: for DNA preparation, an Instagene matrix (Bio-Rad, Richmond, Calif.) was used as described previously (17). Amplified PCR products were then resolved by agarose gel electrophoresis (2%, wt/vol) and stained with ethidium bromide (5 μg/ml). Visualization was achieved by UV illumination, and images were captured by using a GelDoc 1000 image analysis station.

stx1 subtyping.

The Clustal W program was used to align stx1 genes deposited in GenBank, and the Mapplot program, accessed via the Australian National Genomic Information Service (ANGIS) (www.angis.org.au), was used to identify restriction enzyme cleavage sites. Since all Shiga toxin 1 gene sequence variants with the exception of stx1c display more than 99% sequence identity with stx1933J, all non-stx1c sequences will be referred to as stx1 subtypes in this report. To subtype stx1 sequences, a 603-bp fragment of the gene was amplified by using the Gannon F and R primers (Table 2). Restriction enzymes CfoI and RsaI were used to cut the 603-bp fragment because they were predicted to generate RFLP profiles that readily distinguish stx1c from other stx1 subtypes. PCR assays were carried out in a 50-μl total volume containing 5 μl of a whole-cell DNA template prepared by using an Instagene matrix (17), 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 10 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 10 pmol of each primer, 200 μM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, and 1 U of Taq DNA. Thermocycler steps included an initial denaturation step of 94°C for 180 s, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation (94°C for 60 s), annealing (60°C for 60 s), and extension (72°C for 120 s). A final extension step of 72°C for 300 s completed the PCR. The PCR product (3 to 5 μg) was separately digested with 5 U each of CfoI and RsaI in 1× buffer L (Roche Pharmaceuticals) and was incubated at 37°C for a minimum of 4 h. Agarose gel (2%) electrophoresis was used to separate the restricted fragments, and subtypes were identified according to their restriction patterns.

TABLE 2.

Primers used to amplify and sequence stx1

| Primer name | Primer sequence | Size (bp) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| stx1 typing | |||

| Gannon F | 5′-ACACTGGATGATCTCAGTGG-3′ | 603 | 21 |

| Gannon R | 5′-CTGAATCCCCCTCCATTATG-3′ | ||

| stx1 sequencing | |||

| Paton 1F | 5′-TCGCA-TGAGATCTGACC-3′ | 1,470 | 43 |

| Paton 1 R | 5′-AACTGACTGAATTGAGATG-3′ | ||

| Paton 2 F | 5′-ATAAATCGCCATTCGTTGACTAC-3′ | 180 | 44 |

| Paton 2 R | 5′-AGAACGCCCACTGAGATCATC-3′ | ||

| Gannon F | 5′-ACACTGGATGATCTCAGTGG-3′ | 603 | 21 |

| Gannon R | 5′-CTGAATCCCCCTCCATTATG-3′ | ||

| Paton 1 F | 5′-TCGCATGAGATCTGACC-3′ | 448 | This study |

| Vidiya 1 R | 5′-AATAAGCCGTAGATTATT-3′ |

Sequence analysis of stx1.

The stx1 genes from two isolates of serotypes O26:H11 (isolate 507) and O5:H− (isolate 904) were sequenced. These isolates were selected because O26:H11 and O5:H− are common serotypes of STEC isolates recovered from healthy adult cattle and sheep, respectively. Secondly, serotype O26:H11 possesses an stx1 RFLP profile that is indistinguishable from those of other stx1 subtypes, and serotype O5:H− possesses an stx1 RFLP profile that is indistinguishable from that of stx1c. A 1,470-bp fragment encoding both A and B subunits of all Shiga toxin 1 genes was amplified by using primers Paton 1F and Paton 1R (Table 2) in a reaction volume of 50 μl. PCR was carried out by using 5 μl of a whole-cell DNA template prepared by using an Instagene matrix (17), 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 10 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 10 pmol of each primer, 200 μM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, and 1 U of Taq DNA polymerase. Thermocycler steps involved an initial denaturation step of 94°C for 180 s, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation (94°C for 30 s), annealing (54°C for 30 s), and extension (72°C for 60 s). A final extension step of 72°C for 300 s completed the PCR. The amplified PCR product was separated by agarose gel electrophoresis (2%) and purified for DNA sequencing by using the QIAquick DNA purification kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Primers used for sequencing are listed in Table 2. Sequencing reactions were performed by using the Big Dye terminator cycle sequencing ready reaction DNA sequencing kit and electrophoresed on an ABI Prism 377 DNA sequencer (Perkin-Elmer, Santa Clara, Calif.) as described previously (50). Auto Assembler software (Perkin-Elmer) was used to compile and analyze the DNA sequences. Nucleotide and amino acid analyses were performed by using programs accessed via ANGIS. Sequences were compared with those deposited in public databases by using the BlastN and Blast P algorithms (2).

RESULTS

Detection of STEC virulence factors by multiplex PCR.

Of 378 stx1-containing isolates, 207, 104, and 45 were derived from ovine, bovine, and human sources, respectively. Eleven isolates from New Zealand meat, five serotype O157:H− isolates recovered from porcine feces, five isolates from unknown sources, and a single isolate cultured from a water trough completed the collection. Among the 207 ovine isolates, the predominant virulence factor combinations were represented by 108 isolates (52.2%) with stx1, stx2, and ehxA; 46 isolates (22.2%) with stx1 and ehxA; 22 isolates (10.6%) with stx1 and stx2; 11 isolates (5.3%) with stx1 alone; 9 isolates (4.3%) with stx1, eaeA, and ehxA; and 7 isolates (3.4%) with all four factors. Of 104 bovine isolates, 54 (52.0%) contained stx1, stx2, and ehxA; 24 (23.1%) contained stx1, ehxA, and eaeA; 6 (5.8%) contained stx1 only; 6 (5.8%) possessed stx1 and ehxA; 7 (6.7%) contained all four factors; 6 (5.8%) possessed stx1 and stx2; and 1 (0.96%) possessed stx1, stx2, and eaeA. Of 45 human isolates, 20 (44.4%) contained stx1, ehxA, and eaeA; 6 (13.3%) contained stx1, stx2, and ehxA; 5 (11.1%) contained stx1 and stx2; 4 (8.9%) contained stx1 and eaeA; 3 (6.7%) contained stx1 alone; 4 (8.9%) contained stx1 and ehxA; 2 (4.4%) contained all four factors; and 1 (2.2%) contained stx1, stx2, and ehxA. Of the 11 meat isolates, 7 (63.6%) contained stx1, stx2, and ehxA; 3 (27.3%) contained stx1 alone; and 1 (9.1%) contained stx1 and ehxA. All five porcine O157:H− isolates included in this study were positive for stx1, eaeA, and ehxA. STEC serotypes and their virulence factor profiles are listed in Table 1.

Development of a PCR-RFLP assay to identify stx1c.

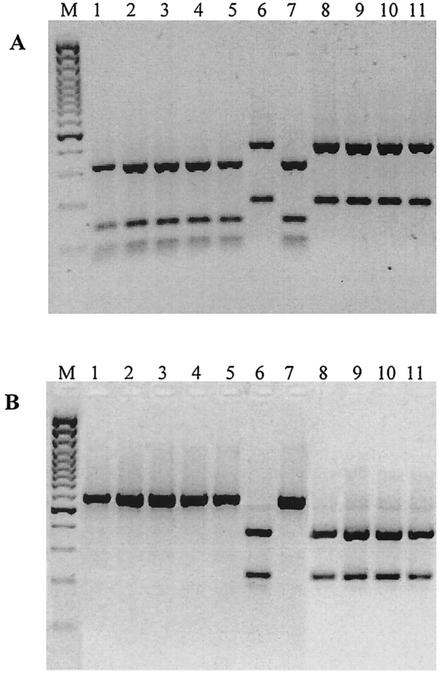

RFLP patterns generated by separate digestions of a 603-bp fragment of stx1 with CfoI and RsaI are shown in Fig. 1A and B, respectively. The 603-bp fragment amplified from STEC isolates possessing stx1 subtypes (defined as stx1 subtypes that share more than 99% nucleotide sequence identity with stx1933J) generated fragments of 322, 135, 83, and 63 bp with CfoI and 603 bp with RsaI (Fig. 1, lanes 1 to 5 and 7). However, the 603-bp fragment amplified from STEC isolates possessing stx1c generated fragments of 414 and 189 bp with CfoI and 386 and 217 bp with RsaI, respectively (Fig. 1, lanes 6 and 8 to 11). This assay was used to type stx1 from 378 stx1-containing STEC isolates (Table 1).

FIG. 1.

CfoI (A) and RsaI (B) digests of PCR products obtained with primers Gannon F and Gannon R. Lanes: M, 100-bp Plus marker; 1, O82:H8 (bovine feces); 2, O3:H7 (bovine feces); 3, O26:H11 (bovine feces); 4, OX3:H8 (bovine feces); 5, O130:H11 (bovine feces); 6, O5:H− (ovine feces); 7, O91:H− (ovine feces); 8, O123:H− (ovine feces); 9, O75:H8 (ovine feces); 10, O128:H2 (ovine feces); 11, O123:H− (ovine feces).

stx1 subtyping and association with serotype.

Of 207 ovine isolates, 136 (65.7%) possessed stx1c, 52 (25.1%) possessed an stx1 subtype, and 19 (9.2%) concomitantly possessed both stx1c and stx1 subtypes. Interestingly, STEC isolates that possessed both stx1c and stx1 were all (except one isolate) of ovine origin and belonged either to serotype O75:H8 (accounting for 14 of the 21 ovine isolates with this serotype) or to one of the following serotypes (each represented by a single isolate): O103:H38, Ont:H8, O88:H8, O55:H20, and O5:HR. A single bovine isolate (serotype O37:H10) possessed both stx1c and a common stx1 subtype (Table 1).

Ovine STEC isolates positive for stx1c alone comprised 41 serotypes, of which the most common were O128:H2 (with all 28 isolates of this serotype positive for stx1c alone), O5:H− (all 22 isolates), O123:H− (all 21 isolates), Ont:HR (all 9 isolates), O153:H25 (all 5 isolates), O91:H− (5 of 32 isolates), O75:H8 (4 of 21 isolates), and OX3:HR (all 3 isolates). With the exception of isolates with serotypes OR:H−/H2/H4, O6:H−, and O75:H40, the remaining 28 serotypes containing stx1c were represented by a single isolate (Table 1).

Ovine isolates that possessed stx1 alone belonged to serotypes O26:H− (with both ovine isolates of this serotype possessing stx1 alone), O26:H11 (all 4 isolates), O91:H− (27 of 32 isolates), O157:H− (4 of 4 isolates), O75:H8 (3 of 21 isolates), O112ab:H2 (3 of 4 isolates), and Ont:H− (2 of 3 isolates); each of the remaining serotypes was represented by a single isolate (Table 1). Serogroup O26 strains are not commonly isolated from ovine feces (14). Six isolates belonging to serogroup O26 included in this study were recovered from newborn lambs during intensive sampling on a property that simultaneously grazed sheep and cattle, and their stx1 subtypes were indistinguishable from stx1 subtypes found in O26 isolates recovered from cattle.

Of 104 bovine isolates possessing stx1, 97 (93.3%) contained an stx1 subtype and belonged to 44 serotypes including O26:H11 (13 of 13 bovine isolates of this serotype), O3:H7 (7 of 7 isolates), O82:H8 (6 of 6 isolates), Ont:H11 (6 of 6 isolates), O5:H− (6 of 8 isolates), O5:H7 (3 of 3 isolates), O108:H7 (4 of 4 isolates), O82:H40 (2 of 2 isolates), O111:H− (2 of 2 isolates), O111:H8 (2 of 2 isolates), O113:H4 (2 of 2 isolates), O113:H21 (2 of 2 isolates), O130:H11 (3 of 3 isolates), O130:H38 (2 of 2 isolates), and O157:H7 (2 of 2 isolates); the remaining serotypes were each represented by a single isolate (Table 1). Only 6 of 104 (5.8%) bovine isolates contained stx1c. Those containing stx1c alone belonged to serotypes O5:H− (accounting for two of eight bovine isolates of this serotype), O153:H8 (one isolate), O117:H21 (one isolate), Ont:H4 (one isolate), and Ont:H10 (one isolate). A single isolate of serotype O37:H10 contained both stx1c and stx1 subtypes (Table 1).

Of 45 human isolates, 31 were isolated from patients with diarrhea (25 isolates, 7 serotypes) or HUS (6 isolates, 3 serotypes) (Table 1). Two isolates (both serotype O91:H−) were recovered from an asymptomatic patient, and one isolate was from a healthy individual (serotype Ont:Hnt). Of the remaining 11 human isolates, recovered from patients of unknown health status, 4 (serotypes O81:H6, O26:H11, Ont:H−, and OR:H−) were from New Zealand, 3 (2 with serotype O157:H7 and one with OR:H7) were recovered during a HUS outbreak in Japan in 1996, 2 (both serotype O111:H−) were from Italy, 1 (serotype O157:H7, associated with the Jack-in-the-Box-outbreak) was from the United States, and 1 was from Australia (serotype Ont:H−) (Table 1). All six human isolates with serotype O128:H2 (diarrhea), four O5:H− (HUS) isolates, one isolate with serotype O123:H− (diarrhea), and one isolate with OX3:H8 (HUS)—all serotypes frequently isolated from sheep—as well as a single isolate of serotype O81:H6 from a patient in New Zealand possessed stx1c. Twelve isolates with serotype O26:H11 and 3 with serotype O26:H− (14 of these 15 isolates were recovered from patients with diarrhea), both serotypes commonly isolated from bovine feces, possessed an stx1 subtype. Interestingly, two isolates with serotype O91:H− (recovered from asymptomatic patients), a common ovine serotype, possessed an stx1 subtype. Serotype O91:H− isolates are frequently recovered from ovine feces and are atypical compared with other common ovine STEC serotypes in that they possess an stx1 subtype. Isolates of serotypes O111:H− (two isolates from patients of unknown health status), O117:H7 (two, from patients with diarrhea), O157:H7 (three; unknown health status), and Ont:H2 (two; unknown health status), and one isolate each of serotypes O8:H8 (HUS), O103:H2 (diarrhea), O118:H16 (diarrhea), Ont:Hnt (healthy patient), OR:HR (unknown health status), and OR:H− (unknown health status), all possessed an stx1 subtype. STEC isolates belonging to the classical EHEC types (serogroups O26, O103, O111, O113, and O157) did not possess stx1c alone, an observation that supports the findings of others (30, 63). Of the 11 isolates from New Zealand meat, those with serotypes O5:H−, O75:H8/H40, O81:H26, O88:H25, O104:H−/H7, O123:H−/H10, and O128:H2 all possessed stx1c while 1 isolate of serotype O91:H− possessed an stx1 subtype.

All five O157:H− isolates recovered from healthy pigs included in this study possessed an stx1 subtype (Table 1).

stx1 subtypes in STEC isolates containing the eaeA gene.

Of 90 STEC isolates that contained eaeA, 81 (90%) possessed an stx1 subtype (Table 1). Of the remaining nine isolates (serotypes O5:HR, O37:H10, O55:H20, O88:H8, and Ont:H8), five contained both common stx1 and stx1c subtypes and four (serotypes O5:H−, O106:HR, O123:H−, and O158:HR) contained the stx1c subtype (Table 1). These data suggest that STEC isolates containing eaeA predominantly possess an stx1 subtype.

stx1 sequence analysis.

stx1 from isolates of serotypes O26:H11 (isolate 507) and O5:H− (isolate 904), which were predicted by RFLP analyses to possess stx1 and stx1c subtypes, respectively, and which were representative of the two stx1 RFLP patterns identified in this study, were examined by DNA sequence analysis. The stx1 sequence derived from serotype O26:H11 showed a single nucleotide difference (A→T) from the stx1J933 sequence (GenBank accession no. AF034975.3) (38) in the A subunit (S67→T). The nucleotide sequence derived from serotype O5:H− showed 100% homology with the reported stx1c gene sequence (accession no. Z36901.1) (43).

DISCUSSION

This study describes the development of a PCR-RFLP assay that differentiates stx1c from other stx1 subtypes and its application for subtyping stx1 genes in 378 STEC isolates predominantly from feces of various meat-producing animals and humans. The most striking result of this study was the predominance of stx1c (136 of 207 isolates [65.7%]) in STEC isolated from ovine feces and the infrequent identification of this subtype in STEC from bovine feces (6 of 104 isolates [5.8%]). Of the 207 ovine STEC isolates, 70 (33.8%) belonged to the common ovine serotypes O5:H−, O128:H2, and O123:H− (5-7, 14, 30, 50, 58; our unpublished data) and were positive for the stx1c gene. Isolates with serotype O91:H−, another commonly reported ovine STEC serotype (14, 30, 58), predominantly possessed an stx1 subtype (27 of 32 isolates [84.4%]), although 5 isolates possessed stx1c. In similar studies of ovine STEC, all 10 O91:H− isolates from Germany (30) and 12 O91:H− isolates from Norway (58) were reported to possess an stx1 subtype, suggesting that this serotype is rarely infected by lysogenic phage carrying stx1c (see below). Urdahl et al. (58) suggested that STEC isolates belonging to the O91 serogroup might be less host specific than those of other serotypes, since they have been isolated from cattle, sheep, pigs, goats, and humans and are found with different flagellar types including H−, H10, H14, H21, and H49.

In our study, the stx1c gene was identified among a serologically diverse collection of STEC isolates, the vast majority of which have been recovered only from ovine feces (14, 27, 30, 58; our unpublished data). In a study of sheep in Germany, stx1c was detected in 48 stx1-containing STEC isolates comprising serogroups O5, O125, O128, O146, and OX3 (30). A study in Norway (58) reported stx1c in 73 of 102 (71.6%) stx1-positive isolates, belonging to 12 different serotypes, from ovine feces; serotypes O5:NM, O6:H10, O91:NM, and O128:NM predominated. A lysogenic bacteriophage carrying the stx1c gene has been isolated from STEC derived from ovine feces, and the ability of the phage to integrate into the genomes of genetically heterogeneous E. coli types has been established (30). The authors suggested that the promiscuous nature of this bacteriophage may provide an explanation for the presence of the stx1c gene among serologically diverse populations of STEC belonging to different clonal lineages. Our study confirms and extends these preliminary observations by showing that the stx1c gene is present among 51 STEC serotypes predominantly of ovine origin. The low prevalence of this gene in STEC recovered from bovine sources (6 of 104 isolates [5.8%]) suggests that either phage carrying stx1c are not prevalent in the gastrointestinal tracts of cattle or most serotypes that inhabit cattle are refractory to infection by this phage.

Although STEC strains of serotype O5:H− are predominantly isolated from sheep and not cattle (5, 14, 58), they are occasionally isolated from the latter. Eight serotype O5:H− isolates from cattle were included in this study. Three of these STEC isolates were recovered from young calves, and two of these possessed stx1c; the other five O5:H− isolates were recovered from diarrheic cattle and possessed an stx1 subtype. Hornitzky et al. have recovered only one O5:H− STEC isolate from healthy Australian cattle despite intensive fecal sampling (27), and this serotype was not reported among STEC isolates recovered from healthy cattle in studies undertaken in Japan (29), France (49), and Spain (9). However, serotype O5:H− STEC isolates have previously been recovered from diarrheic calves in Australia (26), the United States (15), Argentina (42), and Germany (60) and from healthy cattle in two studies (22, 28). In one of the studies of healthy cattle (22), all 10 bovine O5:H− isolates were shown to simultaneously possess stx1, eaeA, and ehxA. Furthermore, O5:H− isolates recovered from diarrheic calves in Germany (60), Argentina (42), and Australia (26) all possessed eaeA. O5:H− isolates recovered from healthy sheep (14, 58; our unpublished data) very rarely possess eaeA. These data suggest the existence of different clonal populations of serotype O5:H−, and further genetic studies are in progress to test this hypothesis.

Of 207 ovine stx1-containing STEC isolates, 20 (9.7%) possessed eaeA. Of these, 13 contained an stx1 subtype, 3 contained stx1c, and the remaining 4 contained both stx1 and stx1c subtypes. Similarly, 32 of 104 (30.8%) bovine stx1-containing STEC isolates possessed eaeA and none contained stx1c. Of the 165 isolates in this study that possessed the stx1c gene, 137 (83.0%) were found to contain ehxA. Isolates with STEC serotypes that are commonly recovered from patients with serious diseases typically carry the eaeA gene and also possess the EHEC plasmid, which encodes ehxA and other potential virulence-associated factors (10, 22, 61). The majority (82 of 136 [60.3%]) of ovine STEC isolates that possessed stx1c also contained stx2. Previous studies have shown that STEC isolates recovered from ovine feces typically possess the stx2d subtype (50, 58), a subtype that is not commonly found in STEC isolated from patients with severe disease (19, 46, 47). A study of STEC recovered from sheep in Norway reported that 44 of 57 stx2-positive isolates possessed stx2d (58). Collectively, these data lend weight to the hypothesis that STEC isolates recovered from sheep feces are not commonly associated with HUS. However, it should be emphasized that we have characterized five STEC isolates from humans with HUS (four O5:H− isolates and a single OX3:H2 isolate) that did possess stx1c. In addition, 51 of 207 (24.6%) ovine isolates contained an stx1 subtype, and 41 (80.4%) of these belonged to serogroups (O26, O91, O103, and O157) which have been associated with serious human illnesses in Australia and around the world. Thus, the ability to identify stx1c-positive STEC isolates is of clinical and epidemiological significance, because these isolates are likely to be less pathogenic for humans. Limited studies in Australia (4) indicate that STEC serotypes O123:H− and O128:H2, serotypes that typically possess stx1c and that are commonly recovered from the feces of sheep, are isolated from humans with diarrhea but without HUS (4). Similarly, investigators reported from a study in Germany (19) that STEC isolates simultaneously possessing stx2d and stx1 (stx1 not subtyped) were from asymptomatic patients (11 isolates) or patients with diarrhea but without HUS (26 isolates) and that none of them possessed eae. Although the stx1 subtype was not reported in that study (19), our study shows that stx1c is typically associated with STEC strains that possess stx2d. Furthermore, 16 of these 37 isolates (43.2%) possessed serotypes O75:H8, O91:H−, and O128:H−/H2/Hnt, which are common ovine serotypes. Further studies are required to elucidate the contribution of STEC derived from ovine sources to milder human gastrointestinal conditions such as diarrhea.

Of 104 bovine STEC isolates, 97 (93.3%) contained an stx1 subtype and comprised 44 serotypes; 22 of these 97 (22.7%) belonged to serogroups O26, O111, O113, O157, and OX3, which are associated with serious disease in humans in Australia (16) and around the world. We and others have recently shown that the majority of bovine STEC isolates that contain stx2 together with either of the associated virulence factors ehxA and eaeA possess stx2 and stx2vhb subtypes (3; our unpublished data). These subtypes are commonly associated with STEC recovered from seriously diseased patients. Collectively, these data suggest that cattle are the reservoir of STEC strains belonging to a diverse collection of serotypes, a subset of which is capable of causing serious human disease.

There is mounting evidence that STEC serotypes that commonly inhabit the gastrointestinal tract of one ruminant species are rarely isolated from other hosts (5-7, 14, 27, 30, 50, 58; our unpublished data). Shiga toxin gene subtypes also appear to associate with particular STEC serotypes and consequently with particular ruminant hosts. For example, stx2-containing STEC isolates recovered from ovine feces commonly possess stx2d subtypes (46, 50, 58) whereas stx2-containing STEC isolates commonly recovered from cattle feces typically possess stx2, stx2vha, and stx2vhb subtypes (3; our published data). Similarly, stx2e-containing STEC is typically isolated from porcine sources and has not to our knowledge been recovered from ovine or bovine sources (14, 26, 27, 30, 50, 58), and stx2f-containing STEC is typically recovered from pigeons (53). These observations are consistent with hypotheses raised by Hoey et al. (25) which suggest that the effects of Shiga toxins on bovine epithelial cells are likely to significantly affect the success of colonization, dissemination, and persistence of STEC in cattle reservoirs. Furthermore, these authors also speculate that genetic heterogeneity among both Shiga toxin subtypes and other associated virulence factors, particularly serotype-dependent variation, may account for differences in the pathogenicity of different STEC populations for cattle and hence the potential for distribution in humans.

In contrast to these observations, O157 STEC can be isolated from different animal species including humans, cattle, sheep, and swine (12, 14, 24, 37). Irrespective of host source, O157 isolates have never been shown to possess stx1c or stx2d genes and always possess either the stx1 or the stx2 and/or stx2vh subtype, or both (3, 19, 63; our unpublished data). In the present study we also show that some serogroups, particularly O75:H8 (14 of 21 isolates), simultaneously possess both stx1 and stx1c subtypes. Similarly, some bovine STEC isolates have been reported to possess as many as three different stx2 subtypes (3). Shiga toxin genes are uniformly flanked by bacteriophage-linked sequences in serologically different STEC strains (52, 57). Collectively, these observations support the contention that bacteriophage transmission plays a key role in the spread of Shiga toxin genes among E. coli strains and that serotype may influence the outcome of these interactions (30, 51, 52).

Acknowledgments

K. N. Brett is the recipient of a Commonwealth funded postgraduate scholarship as part of the Beef CRC Mark II. V. Ramachandran is the recipient of a University of Wollongong Postgraduate Research Award and an Overseas Postgraduate Scholarship.

K. N. Brett and V. Ramachandran contributed equally to this work.

We thank A. Burnens for supplying STEC strains from Switzerland.

REFERENCES

- 1.Acheson, D. W. K., R. Moore, S. De Breucker, L. Lincicome, M. Jacewicz, E. Skutelsky, and G. T. Keusch. 1996. Translocation of Shiga toxin across polarized intestinal cells in tissue culture. Infect. Immun. 64:3294-3300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul, S. F., W. Gish, W. Miller, E. W. Myers, and D. J. Lipman. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bertin, Y., K. Boukhors, N. Pradel, V. Livrelli, and C. Martin. 2001. Stx2 subtyping of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli isolated from cattle in France: detection of a new Stx2 subtype and correlation with additional virulence factors. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3060-3065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bettelheim, K. A. 2001. Enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7: a red herring? J. Med. Microbiol. 50:201-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beutin, L., D. Geier, H. Steinruck, S. Zimmermann, and F. Scheutz. 1993. Prevalence and some properties of verotoxin (Shiga-like-toxin)-producing Escherichia coli in seven different species of healthy domestic animals. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31:2483-2488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beutin, L., D. Geier, S. Zimmermann, S. Aleksic, H. A. Gillespie, and T. S. Whittam. 1997. Epidemiological relatedness and clonal types of natural populations of Escherichia coli strains producing Shiga toxins in separate populations of cattle and sheep. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:2175-2180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beutin, L., D. Geier, S. Zimmermann, and H. Karch. 1995. Virulence markers of Shiga-like toxin-producing Escherichia coli strains originating from healthy domestic animals of different species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:631-635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blake, D. C. I., R. G. Russell, E. Santini, T. Bowen, and E. C. Boedeker. 1996. Pro-inflammatory mucosal cytokine responses to Shiga-like toxin-1 (SLT-1), p. 75-82. In G. T. Keusch and M. Kawakami (ed.), Cytokines, cholera and the gut. IOS Press, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- 9.Blanco, M., J. E. Blanco, J. Blanco, A. Mora, C. Prado, M. P. Alonso, M. Mourino, C. Madrid, C. Balsalobre, and A. Juarez. 1997. Distribution and characterization of faecal verotoxin-producing Escherichia coli (VTEC) isolated from healthy cattle. Vet. Microbiol. 54:309-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boerlin, P., S. A. McEwen, F. Boerlin-Petzold, J. B. Wilson, R. P. Johnson, and C. L. Gyles. 1999. Associations between virulence factors of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli and disease in humans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:497-503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calderwood, S. B., and J. J. Mekalanos. 1987. Iron regulation of Shiga-like toxin expression in Escherichia coli is mediated by the fur locus. J. Bacteriol. 169:4759-4764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chapman, P. A., C. A. Siddons, D. J. Wright, P. Norman, J. Fox, and E. Crick. 1993. Cattle as a possible reservoir of verotoxin-producing Escherichia coli O157 infections in man. Epidemiol. Infect. 111:439-447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clarke, R. C., J. B. Wilson, S. C. Read, S. Renwick, K. Rahn, R. P. Johnson, D. Alves, M. A. Karmali, H. Loir, S. A. McEwen, J. Spika, and C. L. Gyles. 1994. Verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli (VTEC) in the food chain: preharvest and processing perspectives, p. 17-24. In M. A. Karmali and A. G. Goglio (ed.), Recent advances in verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli infections. Elsevier Science B.V., Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- 14.Djordjevic, S. P., M. A. Hornitzky, G. Bailey, P. Gill, B. Vanselow, K. Walker, and K. Bettelheim. 2001. Virulence properties and serotypes of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli from healthy Australian slaughter-age sheep. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:2017-2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dorn, C. R., D. H. Francis, E. J. Angrick, J. A. Willgohs, R. A. Wilson, J. E. Collins, B. H. Jenke, and S. J. Shawd. 1993. Characteristics of Vero cytotoxin producing Escherichia coli associated with intestinal colonisation and diarrhea in calves. Vet. Microbiol. 36:149-159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elliott, E. J., R. M. Robbins-Browne, E. V. O'Loughlin, V. Bennet-Wood, J. Bourke, P. Henning, G. G. Hogg, J. Knight, H. Powell, and D. Redmond. 2001. Nationwide study of haemolytic uremic syndrome: clinical, microbiological, and epidemiological features. Arch. Dis. Child. 85:125-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fagan, P. K., M. A. Hornitzky, K. A. Bettelheim, and S. P. Djordjevic. 1999. Detection of Shiga-like toxin (stx1 and stx2), intimin (eaeA), and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC) hemolysin (EHEC hlyA) genes in animal feces by multiplex PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:868-872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferens, W. A., and C. J. Hovde. 2000. Antiviral activity of Shiga toxin 1: suppression of bovine leukemia virus-related spontaneous lymphocyte proliferation. Infect. Immun. 68:4462-4469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Friedrich, A. W., M. Bielaszewska, W.-L. Zhang, M. Pulz, T. Kuczius, A. Ammon, and H. Karch. 2002. Escherichia coli harboring Shiga toxin 2 gene variants: frequency and association with clinical symptoms. J. Infect. Dis. 185:74-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gannon, V. P., and C. L. Gyles. 1990. Characteristics of Shiga-like toxin produced by Escherichia coli associated with porcine edema disease. Vet. Microbiol. 24:89-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gannon, V. P., R. K. King, J. Y. Kim, and E. J. Golsteyn Thomas. 1992. Rapid and sensitive method for detection of Shiga-like toxin-producing Escherichia coli in ground beef using the polymerase chain reaction. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:3809-3815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gyles, C., R. Johnson, A. Gao, K. Ziebell, D. Pierard, S. Aleksic, and P. Boerlin. 1998. Association of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli hemolysin with serotypes of Shiga-like-toxin-producing Escherichia coli of human and bovine origins. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:4134-4141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heimer, S. R., R. A. Welch, N. T. Perna, G. Posfai, P. S. Evans, J. B. Kaper, F. R. Blattner, and H. L. T. Mobley. 2002. Urease on enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli: evidence for regulation by Fur and a trans-acting factor. Infect. Immun. 70:1027-1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heuvelink, A. E., J. T. Zwartkruis-Nahuis, F. L. van den Biggelaar, W. J. Leeuwen, and E. de Boer. 1999. Isolation and characterisation of verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli O157 from slaughter pigs and poultry. Int. J. Food Prot. 52:67-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoey, D. E. E., C. Currie, R. W. Else, A. Nutikka, C. A. Lingwood, D. Gally, and D. G. E. Smith. 2002. Expression of receptors for verotoxin 1 from Escherichia coli O157 on bovine intestinal epithelium. J. Med. Microbiol. 51:143-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hornitzky, M. A., K. A. Bettelheim, and S. P. Djordjevic. 2001. The detection of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli in diagnostic bovine faecal samples using vancomycin-cefimine-cefsulodin blood agar and PCR. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 198:17-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hornitzky, M. A., B. A. Vanselow, K. Walker, K. A. Bettelheim, B. Corney, P. Gill, G. Bailey, and S. P. Djordjevic. 2002. Virulence properties and serotypes of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli from healthy Australian cattle. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:6439-6445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson, R. P., R. C. Clarke, J. B. Wilson, S. C. Read, K. Rahn, S. A. Renwick, K. A. Sandhu, D. Alves, M. A. Karmali, H. Loir, S. A. McEwen, J. S. Spika, and C. L. Gyles. 1996. Growing concerns and recent outbreaks involving non-O157:H7 serotypes of verotoxigenic Escherichia coli. J. Food Prot. 59:1112-1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kobayashi, H., J. Shimada, M. Nakazawa, T. Morozumi, T. Pohjanvitra, S. Pelkonnen, and K. Yamamoto. 2001. Prevalence and characteristics of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli from healthy cattle in Japan. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:484-489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koch, C., S. Hertwig, R. Lurz, B. Appel, and L. Beutin. 2001. Isolation of a lysogenic bacteriophage carrying the stx1OX3 gene, which is closely associated with Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli strains from sheep and humans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3992-3998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kudva, I. T., P. G. Hatfield, and C. J. Hovde. 1999. Characterization of Escherichia coli O157:H7 and other Shiga toxin-producing E. coli serotypes isolated from sheep. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:892-899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McNally, A., A. J. Roe, S. Simpson, F. M. Thomson-Carter, D. E. E. Hoey, C. Currie, T. Chakraborty, D. G. E. Smith, and D. L. Gally. 2001. Differences in levels of secreted locus of enterocyte effacement proteins between human disease-associated and bovine Escherichia coli O157. Infect. Immun. 69:5107-5114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 33.Menge, C., L. H. Wieler, T. Schlapp, and G. Baljer. 1999. Shiga toxin 1 from Escherichia coli blocks activation and proliferation of bovine lymphocyte subpopulations in vitro. Infect. Immun. 67:2209-2217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muniesa, M., and J. Jofre. 1998. Abundance in sewage of bacteriophages that infect Escherichia coli O157:H7 and that carry the Shiga toxin 2 gene. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:2443-2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muniesa, M., F. Lucena, and J. Jofre. 1999. Comparative survival of free Shiga toxin 2-encoding phages and Escherichia coli strains outside the gut. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:5615-5618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nakano, M., T. Iida, M. Ohnishi, K. Kurokawa, A. Takahashi, T. Tsukamoto, T. Yasunaga, T. Hayashi, and T. Honda. 2001. Association of the urease gene with enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli strains irrespective of their serogroups. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:4541-4543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nakazawa, M., and M. Akiba. 1999. Swine as a potential reservoir of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O157:H7 in Japan. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 5:833-834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Neely, M. N., and D. I. Friedman. 1998. Functional and genetic analysis of regulatory regions of coliphage H-19B: location of Shiga-like toxin and lysis genes suggest a role for phage functions in toxin release. Mol. Microbiol. 28:1255-1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nicholls, L., T. H. Grant, and R. M. Robbins-Browne. 2000. Identification of a novel genetic locus that is required for in vitro adhesion of a clinical isolate of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli to epithelial cells. Mol. Microbiol. 35:275-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O'Loughlin, E. V., and R. M. Robins-Browne. 2001. Effect of Shiga toxin and Shiga-like toxins on eukaryotic cells. Microbes Infect. 3:493-507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pai, C. H., J. K. Kelly, and G. L. Meyers. 1986. Experimental infection of infant rabbits with verotoxin-producing Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 51:16-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Parma, A. E., M. E. Sanz, J. E. Blanco, J. Blanco, M. R. Viñas, M. Blanco, N. L. Padola, and A. I. Etcheverria. 2000. Virulence genotypes and serotypes of verotoxigenic Escherichia coli isolated from cattle and foods in Argentina. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 16:757-762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Paton, A. W., L. Beutin, and J. C. Paton. 1995. Heterogeneity of the amino-acid sequences of Escherichia coli Shiga-like toxin type-I operons. Gene 153:71-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Paton, A. W., and J. C. Paton. 1998. Detection and characterization of Shiga toxigenic Escherichia coli using multiplex PCR assays for stx1, stx2, eaeA, enterohemorrhagic E. coli hlyA, rfb O111, and rfb O157. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:598-602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paton, A. W., P. Srimanote, M. C. Woodrow, and J. C. Paton. 2001. Characterization of Saa, a novel autoagglutinating adhesin produced by locus of enterocyte effacement-negative Shiga-toxigenic Escherichia coli strains that are virulent to humans. Infect. Immun. 69:6999-7009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pierard, D., G. Muyldermans, L. Moriau, D. Stevens, and S. Lauwers. 1998. Identification of new verocytotoxin type 2 variant B-subunit genes in human and animal Escherichia coli isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:3317-3322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pierard, D., G. Cornu, W. Proesmans, A. Dediste, F. Jacobs, J. Vande Walle, A. Mertens, J. Ramet, S. Lauwers, and the Belgian Society for Infectology and Clinical Microbiology HUS Study Group. 1999. Hemolytic-uremic syndrome in Belgium: incidence and association with verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli infection. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 5:16-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pierard, D., L. Van Damme, L. Moriau, D. Stevens, and S. Lauwers. 1997. Virulence factors of verotoxin-producing Escherichia coli isolated from raw meats. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:4585-4587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pradel, N., V. Livrelli, C. De Champs, J. B. Palcoux, A. Reynaud, F. Scheutz, J. Sirot, B. Joly, and C. Forestier. 2000. Prevalence and characterization of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli isolated from cattle, food, and children during a one-year prospective study in France. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1023-1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ramachandran, V., M. A. Hornitzky, K. A. Bettelheim, M. J. Walker, and S. P. Djordjevic. 2001. The common ovine Shiga toxin 2-containing Escherichia coli serotypes and human isolates of the same serotypes possess a stx2d toxin type. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:1932-1937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schmidt, H., M. Bielaszewska, and H. Karch. 1999. Transduction of enteric Escherichia coli isolates with a derivative of Shiga toxin 2-encoding bacteriophage φ3538 isolated from Escherichia coli O157:H7. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:3855-3861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schmidt, H. 2001. Shiga-toxin-converting bacteriophages. Res. Microbiol. 152:687-695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schmidt, H., J. Scheef, S. Morabito, A. Caprioli, L. H. Wieler, and H. Karch. 2000. A new Shiga toxin 2 variant (Stx2f) from Escherichia coli isolated from pigeons. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:1205-1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sjogren, R., R. Neill, D. Rachmilewitz, D. Fritz, J. Newland, D. Sharpnack, C. Colleton, J. Fondacaro, P. Gemski, and E. Boedeker. 1994. Role of Shiga toxin 1 in bacterial enteritis: comparison between isogenic Escherichia coli strains. Gastroenterology 106:306-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tarr, P. I., S. S. Bilge, J. C. Vary, Jr., S. Jelacic, R. L. Habeeb, T. R. Ward, M. R. Baylor, and T. E. Besser. 2000. Iha: a novel Escherichia coli O157:H7 adherence-conferring molecule encoded on a recently acquired chromosomal island of conserved structure. Infect. Immun. 68:1400-1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thorpe, C. M., B. P. Hurley, L. L. Lincicome, M. S. Jacewicz, G. T. Keusch, and D. W. K. Acheson. 1999. Shiga toxins stimulate secretion of interleukin-8 from intestinal epithelium cells. Infect. Immun. 67:5985-5993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Unkmeir, A., and H. Schmidt. 2000. Structural analysis of phage-borne stx genes and their flanking sequences in Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli and Shigella dysenteriae type 1 strains. Infect. Immun. 68:4856-4864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Urdahl, A. M., L. Beutin, E. Skjerve, and Y. Wasteson. 2002. Serotypes and virulence factors of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli isolated from healthy Norwegian sheep. J. Appl. Microbiol. 93:1026-1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wagner, P. L., M. N. Neely, X. Zhang, and D. W. Acheson. 2001. Role for a phage promoter in Shiga toxin 2 expression from a pathogenic Escherichia coli strain. J. Bacteriol. 183:2081-2085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wieler, L. H., E. Vieler, C. Erpenstein, T. Schlapp, H. Steinruck, R. Bauerfeind, A. Byomi, and G. Baljer. 1996. Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli strains from bovines: association of adhesion with carriage of eaeA and other genes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:2980-2984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Willshaw, G. A., S. M. Scotland, H. R. Smith, and B. Rowe. 1992. Properties of Vero cytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli of human origin of O serogroups other than O157. J. Infect. Dis. 166:797-802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yamasaki, C., Y. Natori, X. T. Zhang, M. Ohmura, S. Yamasaki, Y. Takeda, and Y. Natori. 1999. Induction of cytokines in a human colon epithelial cell line by Shiga toxin 1 (Stx1) and Stx2 but not by non-toxic mutant Stx1 which lacks N-glycosidase activity. FEBS Lett. 442:231-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang, W., M. Bielaszewska, T. Kuczius, and H. Karch. 2002. Identification, characterization, and distribution of Shiga toxin 1 gene variant (stx1c) in Escherichia coli strains isolated from humans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:1441-1446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]