Abstract

Streptococcus iniae, a fish pathogen causing infections in aquaculture farms worldwide, has only been reported to cause human infections in North America. In this article, we report the first two cases of invasive S. iniae infections in two Chinese patients outside North America. While the first patient presented with bacteremic cellulitis, which is the most common presentation in previous cases, the second patient represents the first recognized case of S. iniae osteomyelitis. Both S. iniae strains isolated from the two patients were either misidentified or unidentified by three commercial systems and were only identified by 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Since no currently available commercial system for bacterial identification includes S. iniae in its database, 16S rRNA gene sequencing is the most practical and reliable method to identify the bacterium at the moment. In contrast to the distinct genetic profile described previously in clinical isolates from Canada, the present two isolates and a clinical isolate from a Canadian patient were found to be genetically unrelated, as demonstrated by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Morphologically, colonies of both isolates were also larger, more beta-hemolytic and mucoid, which differ from the usual morphotype described for S. iniae. Owing to their habit of cooking and eating fresh fish, the Asian population is strongly associated with S. iniae infections. As a result of the difficulty in making microbiological diagnosis in patients with cellulitis and the problem of identification in most clinical microbiology laboratories, the prevalence of S. iniae infections, especially in the Asian population, may have been under-estimated.

Streptococcus iniae was first isolated from the subcutaneous abscess of a freshwater dolphin (Inia geoffrensis) in 1976 in the United States (13). Since then, it has been an important fish pathogen, causing sporadic infections in tilapia, yellowtail, rainbow trout, and coho salmon and disease outbreaks with high mortality rates in aquaculture farms in Japan, Taiwan, Israel, and the United States (5, 8, 9, 14). Skin lesions and necrotizing myositis were typical of S. iniae infection of red drum, while meningoencephalitis and panophthalmitis were the main lesions among trout and tilapia (1, 4). Some fish like barramundi and tilapia can carry S. iniae asymptomatically (2, 15).

S. iniae was first recognized to cause human infection during the period from 1995 to 1996, when nine Asian patients in Toronto, Canada, had invasive S. iniae infections. Eight of the nine patients had bacteremic cellulitis, and all nine isolates were genetically related as demonstrated by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) of their genomic DNA after restriction endonuclease digestion (3, 18). Apart from these nine cases, two retrospective and two subsequent cases of S. iniae infections were also identified either in the United States or Canada (7, 18). Despite its global distribution among fish population, S. iniae has not been reported to cause human infection outside North America. In this article, we describe the first two cases of S. iniae infection outside North America, one in an 81-year-old man with bacteremic cellulitis and the other in a 79-year-old man with bacteremic osteomyelitis. The genetic relatedness of these two isolates, an S. iniae type strain isolated from a freshwater dolphin and a clinical isolate from Canada, were studied. The epidemiological potential of this pathogen in the Asian population is also discussed.

CASE REPORTS

Case 1.

An 81-year old Chinese man was admitted in June 2001 because of fever and right leg painful swelling for 1 day. He was known to have apical hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy and had history of duodenal ulcer and gallstones. Physical examination revealed an oral temperature of 39.5°C and right leg cellulitis. His total leukocyte count was 13.5 × 109/liter, hemoglobin level 14.4 g/dl and platelet count 147 × 109/liter. Serum albumin was 40 g/liter, globulin 36 g/liter, bilirubin 20 μmol/liter, alkaline phosphatase 96 IU/liter, aspartate aminotransferase 57 IU/liter, and alanine aminotransferase 42 IU/liter. Renal function tests were within normal limits. Chest radiograph showed mild cardiomegaly. Blood cultures were performed and empirical amoxicillin-clavulanate was administered.

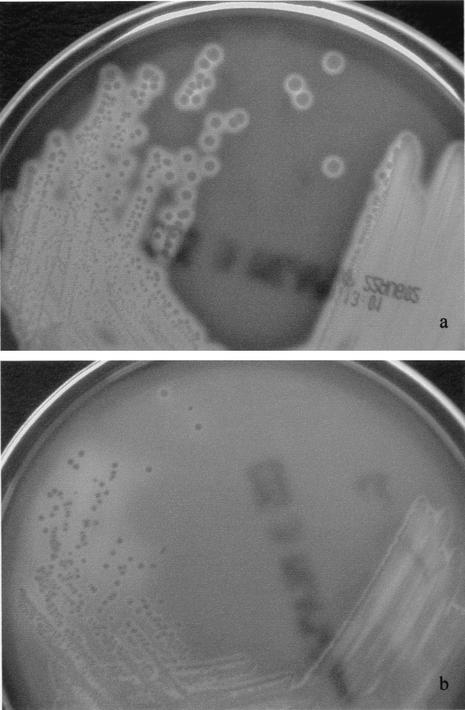

On day 1 postincubation, the aerobic blood culture bottle turned positive with a gram-positive coccus arranged in chains. It grew on sheep blood agar as slightly mucoid, beta-hemolytic colonies of 1 to 2 mm in diameter after 24 h of incubation at 37°C in ambient air (Fig. 1). No enhancement of growth was observed in 5% CO2. It was nongroupable with Lancefield groups A, B, C, D, F, or G antisera. It did not grow in 6.5% NaCl, was nonmotile, and was positive for pyrolidonyl arylamidase and leucine aminopeptidase and negative for arginine or hippurate hydrolysis, bile-esculin, and Voges-Proskauer tests. Both the Vitek system (GPI) and the ATB Expression system (ID32 STREP) showed that it was “unidentified”; whereas the API system (20 STREP) showed that it was 99.9% S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis. It was sensitive to penicillin (MIC = 0.004 μg/ml), erythromycin, tetracycline, cefepime, clindamycin, and vancomycin (MIC = 1 μg/ml).

FIG. 1.

S. iniae cultured on sheep blood agar. Colonies of the present blood culture isolate 1 (a) were larger, more beta-hemolytic and mucoid, when compared to a clinical isolate from a Canada patient (b).

Transthoracic echocardiogram did not show any vegetation or valvular lesion. The patient recalled having handling fresh fish recently, but not any percutaneous injury. Fever and cellulitis subsided with antibiotic therapy and he was discharged after 1 week of hospitalization.

Case 2.

A 79-year old Chinese man was admitted in October 2001 because of low back pain and fever for 2 days. He was a chronic drinker with an otherwise-unremarkable past medical history. He denied any recent back injury. On admission, his oral temperature was 38.9°C. Physical examination revealed spinal tenderness at the L4/5 level but normal lower limb neurology. No sign of trauma or other focus of infection was found on careful examination. His total leukocyte count was 11.1 × 109/liter, hemoglobin level 13.8 g/dl, and platelet count 185 × 109/liter. Liver and renal function tests were within normal limits. Blood cultures were performed and empirical intravenous ampicillin was administered. Radiographs of the lumbar spine showed degenerative changes with osteophyte formation.

On day 1 postincubation, the aerobic blood culture bottle turned positive with a Gram-positive coccus arranged in chains. Apart from positive arginine hydrolysis, it had the same colony morphology, growth requirements and phenotypic characteristics as the isolate from case 1. Both the Vitek system (GPI) and the ATB Expression system (ID32 STREP) showed that it was “unidentified”; whereas the API system (20 STREP) showed that it was 99.9% S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis. It was sensitive to penicillin (MIC = 0.004 μg/ml), erythromycin, tetracycline, cefepime, clindamycin, and vancomycin (MIC = 1 μg/ml).

The antibiotic regimen was changed to intravenous penicillin and gentamicin and his fever responded. Transthoracic echocardiogram did not reveal any vegetations. Both Tc-99m bone scintigraphy and Ga-67 gallium scan noted increased uptake limited to the L4/5 region. A diagnosis of streptococcal bacteremic vertebral osteomyelitis was made. The patient also reported recent handling and preparation of fresh fish for Chinese cooking, but could not recall any percutaneous injury. His low back pain improved with 2 weeks of intravenous antibiotics, and he was discharged with oral amoxicillin for 3 months.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and microbiological methods.

All clinical information and relevant investigation results were collected prospectively at the bedside. Each patient was followed up for determining subsequent progress. Clinical specimens were collected and handled according to standard protocols. All suspect colonies were identified by standard conventional biochemical methods (11), the Vitek System (GPI) (bioMerieux Vitek, Hazelwood, Mo.), API system (20 STREP) (bioMerieux Vitek), and ATB Expression system (ID32 STREP) (bioMerieux Vitek). Antimicrobial susceptibility was tested by E-test for penicillin and vancomycin, and Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion method for the other antibiotics, and results interpreted according to the NCCLS criteria (12).

Extraction of bacterial DNA for 16S rRNA gene sequencing.

Bacterial DNA extraction was modified from our previous published protocol (10). Briefly, 80 μl of NaOH (0.05 M) was added to 20 μl of bacterial cells suspended in distilled water, and the mixture was incubated at 60°C for 45 min, and this was followed by the addition of 6 μl of Tris-HCl (pH 7.0), achieving a final pH of 8.0. The resultant mixture was diluted 100-fold, and 5 μl of the diluted extract was used for PCR.

PCR, gel electrophoresis, and 16S rRNA gene sequencing.

PCR amplification and DNA sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene was performed according to our previous publications (19, 20, 21, 22). Briefly, DNase I-treated distilled water and PCR master mix [which contains deoxynucleoside triphosphates, PCR buffer, and Taq polymerase] were used in all PCRs by adding 1 U of DNase I (Pharmacia, Sweden) to 40 μl of distilled water or PCR master mix, incubating the mixture at 25°C for 15 min, and subsequently at 95°C for 10 min to inactivate the DNase I. The bacterial DNA extract and control were amplified with 0.5 μM primers (LPW200 5′-GAGTTGCGAACGGGTGAG-3′ and LPW205 5′-CTTGTTACGACTTCACCC-3′). The PCR mixture (50 μl) contained bacterial DNA, PCR buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.3], 50 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.01% gelatin), a 200 μM concentration of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, and 1.0 U of Taq polymerase (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany). The mixtures were amplified in 40 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 60°C for 1 min and 72°C for 2 min, and a final extension at 72°C for 10 min in an automated thermal cycler (Perkin-Elmer Cetus, Gouda, The Netherlands). DNase I-treated distilled water was used as the negative control. 10 μl of each amplified product was electrophoresed in 1.5% (wt/vol) agarose gel, with a molecular size marker (φX174 HaeIII digest, Boehringer Mannheim, Germany) in parallel. Electrophoresis in Tris-borate-EDTA buffer was performed at 100 V for 1.5 h. The gel was stained with ethidium bromide (0.5 μg/ml) for 15 min, rinsed and photographed under 312-nm UV light illumination.

The PCR products were gel-purified using the QIAquick PCR purification kit (QIAgen, Hilden, Germany). Both strands of the PCR product were sequenced twice with an ABI 377 automated sequencer according to the manufacturer's instructions (Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, Calif.), using the PCR primers (LPW200 and LPW205). The sequences of the PCR products were compared with known 16S rRNA gene sequences in the GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) by multiple sequence alignment using the CLUSTAL W program (17), and phylogenetic tree construction was performed using PileUp and neighbor-joining method with GrowTree (Genetics Computer Group, Inc., San Diego, Calif.).

PFGE.

PFGE was performed on the two S. iniae strains isolated from our two patients, an S. iniae type strain isolated from a freshwater dolphin (ATCC 29178), and an S. iniae strain isolated from a Chinese patient in Canada, who had cellulitis of the hand after handling tilapia. Briefly, overnight broth cultures of each bacterial strain were subcultured and incubated to an optical density of 0.6 using a 600-nm-visible-light transilluminator, which corresponded to approximately 5 × 108 bacterial cells per ml. One milliliter of each standardized culture was used for preparation of 200-μl agarose plugs, which were subjected to restriction endonuclease SmaI (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany) digestion. PFGE of the gel was performed using the CHEF Mapper XA System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.), with avlambda ladder as the molecular size marker, for 27 h at 14°C, 6 V per cm, an included angle of 120°, and pulse times of 33.28 to 58.93 s in 0.5× TBE buffer (0.045 M Tris-borate, 0.001 M EDTA [pH 8.0]). After electrophoresis, the gel was stained with ethidium bromide and the patterns of the genomic DNA digest were visualized with a 312 nm UV transilluminator. Standard interpretive criteria were used to assess the PFGE patterns (16).

RESULTS

Bacterial identification.

Identification of the bacterial strains was carried out by conventional methods (11) and commercially available identification systems.

16S rRNA gene sequencing.

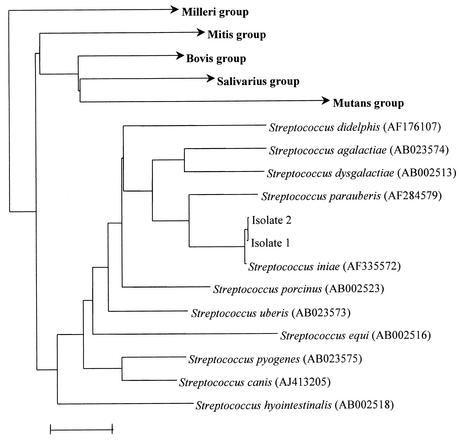

PCR and sequencing of the 1377-bp 16S rRNA genes of the two-blood culture isolates revealed two base differences between the first isolate and S. iniae, and 1 base difference between the second isolate and S. iniae, indicating that both isolates were S. iniae (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Phylogenetic tree showing the relationship of the 2 blood culture isolates from our patients to related species. The tree was inferred from 16S rRNA sequence data by the neighbor-joining method. The scale bar indicates the estimated number of substitutions per 100 bases using the Jukes-Cantor correction. Names and accession numbers are given as cited in the GenBank database.

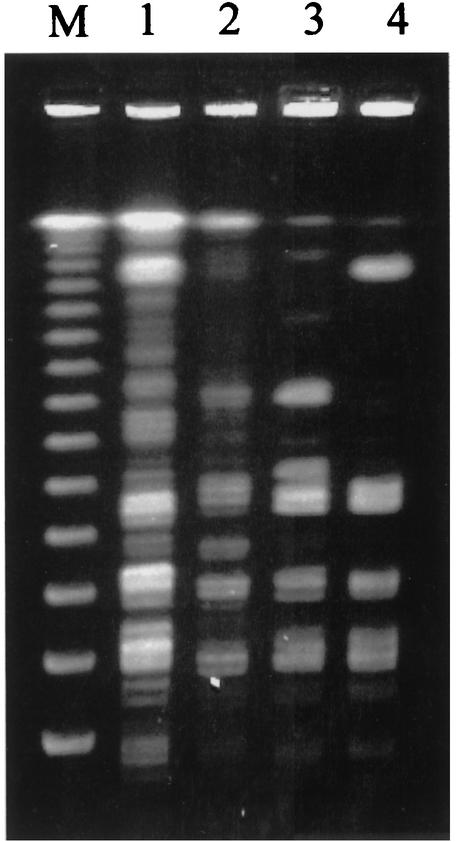

PFGE.

PFGE of the genomic DNA of the two blood culture isolates, the type strain from a freshwater dolphin and the clinical isolate from a Canadian patient after SmaI digestion was shown in Fig. 3. It revealed that our two blood culture isolates were epidemiologically unrelated to either the type strain or the clinical isolate from Canada.

FIG. 3.

PFGE of genomic DNA of the disease-associated strain from Canada (lane 1), the ATCC type strain 29178 from dolphin (lane 2), and isolate 1 (lane 3) and isolate 2 (lane 4) after SmaI digestion and lambda ladder chromosomal DNA size marker (lane M).

DISCUSSION

Despite its global distribution among fish population, S. iniae has not been reported to cause human infection outside North America. After its discovery from a freshwater dolphin in 1976, it was first recognized to cause infections in human only 20 years later. During the winter of 1995 to 1996 in Toronto, there were four cases of invasive S. iniae infections in patients who had handled fresh fish recently (3). A prompt prospective and retrospective surveillance identified, including the four cases, a total of nine patients with invasive S. iniae infections within the 1-year period. One of the patients presented with endocarditis, meningitis, and arthritis, while all the other eight patients had bacteremic cellulitis of the hand. Based on the data from CDC microbiology laboratory, the same report also retrospectively identified two additional cases of S. iniae infection, one in a patient from Texas with bacteremic cellulitis in 1991, and the other in a 79-year-old cook from Ottawa, Canada, with arthritis of the knee in 1994 (18). Subsequently, two additional strains were isolated from patients in Vancouver, Canada, but the clinical details were not described (7) (Table 1). The present report represents the first 2 cases of S. iniae infections outside North America.

TABLE 1.

S. iniae infections reported in the English literature

| Reference | Subject data

|

Method of strain identification | Treatment | Outcome | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yr | Country | Genderc | Age (yr) | Underlying disease | Diagnosis | Recent fish handling | ||||

| 18 | 1991 | United States | NAa | NA | NA | Bacteremic cellulitis | NA | CDCb | NA | NA |

| 18 | 1994 | Canada | M | 79 | NA | Arthritis of knee | NA | CDC | Cloxacillin | NA |

| 18 | 1995 | Canada | F | 74 | None | Bacteremic cellulitis of hand | Yes | Phenotypic | Penicillin | Cued |

| 18 | 1995 | Canada | F | 64 | None | Bacteremic cellulitis of hand | Yes | Phenotypic | Penicillin | Cured |

| 18 | 1995 | Canada | F | 40 | Chronic rheumatic heart disease | Bacteremic cellulitis of hand | Yes | Phenotypic | Penicillin, cloxacillin | Cured |

| 18 | 1996 | Canada | M | 77 | Chronic rheumatic heart disease, chronic renal failure, diabetes mellitus, osteoarthritis | Endocarditis, meningitis, arthritis | Yes | Phenotypic | Erythromycin, cefuroxime | Cured |

| 18 | 1996 | Canada | M | 80 | Diabetes mellitus, osteoarthritis | Bacteremic cellulitis of hand | Yes | Phenotypic | Ampicillin | Cured |

| 18 | 1996 | Canada | F | 69 | None | Bacteremic cellulitis of hand | Yes | Phenotypic | Cloxacillin | Cured |

| 18 | 1996 | Canada | F | 70 | Diabetes | Bacteremic cellulitis of hand | Yes | Phenotypic | Ampicillin, cephalexin | Cured |

| 18 | 1996 | Canada | M | 71 | None | Bacteremic cellulitis of hand | Yes | Phenotypic | Penicillin | Cured |

| 18 | 1996 | Canada | F | 58 | None | Bacteremic cellulitis of hand | Yes | Phenotypic | Penicillin | Cured |

| 7 | NA | Canada | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 7 | NA | Canada | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| This study (case 1) | 2001 | China | M | 81 | Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy, duodenal ulcer, gallstones | Bacteremic cellulitis of leg | Yes | 16S rRNA gene sequencing | Amoxicillin-clavulanate | Cured |

| This study (case 2) | 2001 | China | M | 79 | Alcoholism | Bacteremic osteomyelitis | Yes | 16S rRNA gene sequencing | Penicillin, gentamicin | Cured |

NA, not available.

CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Abbreviations: M, male; F, female.

Although the incidence is not high, the S. iniae infections reported in the literature are serious. Apart from the case of arthritis of the knee, bacteremia is present in all other cases of S. iniae infections with clinical details described (Table 1). The first patient in this article presented with bacteremic cellulitis, which is the most common presentation of S. iniae infections, although the hand was more often involved in previous cases. The strong association between S. iniae and cellulitis suggests that the skin is an important portal of entry and a common primary site of infection. On the other hand, the second case represents the first recognized case of S. iniae osteomyelitis. Since there was no evidence of trauma or cellulitis over the area of spinal tenderness, the vertebral osteomyelitis in the patient was most likely secondary to bacteremic seeding rather than the direct extension of a skin or soft tissue lesion. The ability of S. iniae to cause bacteremic cellulitis as in the case of S. pyogenes and S. dysgalactiae, and osteomyelitis, as in the case of S. pneumoniae and S. agalactiae, suggests that its virulence is comparable to other streptococci. Despite its invasiveness, most of the reported S. iniae infections responded to antibiotic treatment, which was mainly penicillin-based (Table 1). As in the case of all clinical isolates from Canada, the two S. iniae isolates in the present report were also susceptible to penicillin (18). Penicillin therapy should be considered the treatment of choice for S. iniae infections.

Although older age and the presence of underlying disease appear to be risk factors for invasive S. iniae infections (Table 1), the Asian population is a clear overrepresentation. All the nine patients from Toronto with invasive S. iniae infections were of Asian origin and both patients in the present report were Chinese. The strong association between S. iniae infection and the Asian population is best explained by the different methods of cooking fish by different ethnic groups. In contrast to western cooking in which killed fish with appendages removed is purchased and used, preparation of fresh fish is a common practice in domestic Asian cooking. In our locality, for instance, preparing fresh, whole fish is almost a daily routine in every household. Therefore, the chance of hand injuries during the process and contamination of wound by colonizers or pathogens of fish, such as S. iniae, would be much higher in the Asian population. Of the nine patients from Toronto, all had handled fresh fish recently and eight recalled injuring their hands when preparing fish. Six of the nine fish were tilapia, which is commonly used in Asian cooking. Using PFGE, the authors identified a single clone of S. iniae causing infections in all the nine cases, the two retrospective cases and infected tilapia, and colonizing the surface of tilapia sampled from fish stores and suppliers in Canada, which supported the transmission of the bacteria from fish to humans (18). Both patients in the present study also recalled recent history of handling fresh fish, but a specific fish type was not identified.

S. iniae infections in the Asian population are probably underdiagnosed. First, the clinical presentations of S. iniae cellulitis are indistinguishable from cellulitis caused by Staphylococcus aureus, S. pyogenes and other beta-hemolytic Streptococci. Second, culture documentation is often difficult or even not attempted in patients with cellulitis. Moreover, culture-negative S. iniae cellulitis will likely respond to the usual treatment for cellulitis. Therefore, cases of S. iniae nonbacteremic cellulitis may be easily missed. Third, even in the presence of a positive culture, S. iniae may be misidentified in clinical microbiology laboratories. Of the nine clinical isolates of S. iniae from patients in Toronto, six were identified as S. uberis, and the remaining reported as “unidentified” by a commercial system (18). The 2 isolates in this study were also unidentified by two commercial systems and misidentified as S. dysgalactiae by another, while 16S rRNA gene sequencing unambiguously identified both as S. iniae. Up to the present moment, no commercial system includes S. iniae in its database. Therefore, conventional biochemical methods may fail to identify S. iniae from clinical specimens. As PCR and sequencing techniques are becoming more readily available in clinical laboratories, 16S rRNA gene analysis is a more reliable and practical approach to identify this bacterium and other Streptococcus species (20, 21). While bedside clinicians need to be aware of the circumstances where S. iniae infections should be considered, microbiology laboratory staff should be alerted to specimens collected in the clinical setting of soft tissue injuries with history of fish handling. Defining S. iniae infection is important to better delineate its epidemiology and public health implications.

Invasive S. iniae infections outside North America are caused by strains with different genetic profiles. It has been suggested that S. iniae virulence is associated with a distinct genetic profile. Strains of S. iniae causing disease in either fish or humans from Canada were shown to belong to a single clone by PFGE, while isolates from nondiseased fish were genetically diverse (18). Recently, a study has confirmed that the unique genetic profile of disease-associated S. iniae isolates correlated with virulence, which may be responsible for pathogenicity. In vitro models have shown that disease-associated strains were more resistant to phagocytic clearance and direct cytotoxicity to human endothelial cells, when compared to non-disease-associated strains. Moreover, only the disease-associated strains were found to cause significant weight loss and bacteremia in a mouse model of subcutaneous infection (6). However, analysis of the PFGE patterns in the present study revealed that the present two blood culture isolates and the clinical isolate from a Canadian patient are epidemiologically unrelated. This suggests that invasive S. iniae infections can be caused by strains with different genetic profiles. Morphologically, colonies of both strains in the present study appear larger, more beta-hemolytic and mucoid than the clinical isolate from Canada (Fig. 1). These characteristics also differ from the smaller, drier colonies with rainbow hemolysis described for S. iniae morphotypes and are in line with our earlier observations that clinical isolates of S. zooepidemicus in our locality are also larger and exclusively mucoid because of thick capsules of hyaluronic acid (23). Virulence factors responsible for pathogenicity in humans are probably present in more than one clone of S. iniae.

Acknowledgments

This work was partly supported by the University Development Fund, University Research Grant Council, and the Committee of Research and Conference Grants, The University of Hong Kong.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bercovier, H., C. Ghittino, and A. Eldar. 1997. Immunization with bacterial antigens: infections with streptococci and related organisms. Dev. Biol. Stand. 90:153-160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bromage, E. S., A, Thomas, and L. Owens. 1999. Streptococcus iniae, a bacterial infection in barramundi Lates calcarifer. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 36:177-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1996. Invasive infection due to Streptococcus iniae—Ontario, 1995-1996. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 45:650-653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eldar, A., S. Perl, P. F. Frelier, and H. Bercovier. 1997. Red drum Sciaenops ocellatus mortalities associated with Streptococcus iniae infection. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 36:121-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eldar, A., Y. Bejerano, and H. Bercovier. 1994. Streptococcus shiloi and Streptococcus difficile: two new streptococcal species causing a meningoencephalitis in fish. Curr. Microbiol. 28:139-143. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fuller, J. D., D. J. Bast, V. Nizet, D. E. Low, and J. C. de Azavedo. 2001. Streptococcus iniae virulence is associated with a distinct genetic profile. Infect. Immun. 69:1994-2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goh, S. H., D. Driedger, S. Gillett, D. E. Low, S. M. Hemmingsen, M. Amos, D. Chan, M. Lovgren, B. M. Willey, C. Shaw, and J. A. Smith. 1998. Streptococcus iniae, a human and animal pathogen: specific identification by the chaperonin 60 gene identification method. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:2164-2166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kitao, T., T. Aoki, and R. Sakoh. 1981. Epizootic caused by beta-hemolytic Streptococcus species in cultured freshwater fish. Fish Pathol. 19:173-180. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kusuda, R. 1992. Bacterial fish diseases in marineculture in Japan with special emphasis on streptococcosis. Isr. J. Aquacult. 44:140. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lau, S. K. P., P. C. Y. Woo, J. L. L. Teng, K. W. Leung, and K. Y. Yuen. 2002. Identification by 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequencing of Arcobacter butzleri bacteraemia in a patient with acute gangrenous appendicitis. Mol. Pathol. 55:182-185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murray, P. R., E. J. Baro, M. A. Pfaller, F. C. Tenover, and R. H. Yolken (ed.). 1999. Manual of clinical microbiology, 7th ed. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 12.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2001. Performance standards for antimicrobial disk susceptibility tests. Approved standard M2-A7, 7th ed. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 13.Peir, G. B., and S. H. Madin. 1976. Streptococcus iniae sp. nov., a beta-hemolytic streptococcus isolated from an Amazon freshwater dolphin, Inia geoffrensis. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 26:545-553. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perera, R. P., S. K. Johnson, M. D. Collins, and D. H. Lewis. 1994. Streptococcus iniae associated with mortality of Tilapia nilotica and T. aurea hybrids. J. Aquat. Anim. Health 6:335-340. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shoemaker, C. A., P. H. Klesius, and J. J. Evans. 2001. Prevalence of Streptococcus iniae in tilapia, hybrid striped bass, and channel catfish on commercial fish farms in the United States. Am. J. Vet. Res. 62:174-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tenover, F. C., R. D. Arbeit, R. V. Goering, P. A. Mickelsen, B. E. Murray, D. H. Persing, and B. Swaminathan. 1995. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:2233-2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thompson, J. D., D. G. Higgins, and T. J. Gibson. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:4673-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weinstein, M. R., M. Litt, D. A. Kertesz, P. Wyper, D. Rose, M. Coulter, A. McGeer, R. Facklam, C. Ostach, B. M. Willey, A. Borczyk, D. E. Low, et al. 1997. Invasive infections due to a fish pathogen, Streptococcus iniae. N. Engl. J. Med. 337:589-594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Woo, P. C. Y., A. M. Y. Fung, S. K. P. Lau, G. Y. Wong, and K. Y. Yuen. 2002. Diagnosis of pelvic actinomycosis by 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequencing and its clinical significance. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 43:113-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woo, P. C. Y., A. M. Y. Fung, S. K. P. Lau, S. S. Y. Wong, and K. Y. Yuen. 2001. Group G beta-hemolytic streptococcal bacteremia characterized by 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequencing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3147-3155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woo, P. C. Y., D. M. W. Tam, K. W. Leung, S. K. P. Lau, J. L. L. Teng, M. K. M. Wong, and K. Y. Yuen. 2002. Streptococcus sinensis sp. nov., a novel Streptococcus species isolated from a patient with infective endocarditis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:805-810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yuen, K. Y., P. C. Y. Woo, J. L. L. Teng, K. W. Leung, M. K. M. Wong, and S. K. P. Lau. 2001. Laribacter hongkongensis gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel gram-negative bacterium isolated from a cirrhotic patient with bacteremia and empyema. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:4227-4232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yuen, K. Y., W. H. Seto, C. H. Choi, W. Ng, S. W. Ho, and P. Y. Chau. 1990. Streptococcus zooepidemicus (Lancefield group C) septicaemia in Hong Kong. J. Infect. 21:241-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]