Abstract

To identify antigens specific for the filamentous form of Candida albicans, a combinatorial phage display library expressing human immunoglobulin heavy and light chain variable regions was used to select phage clones capable of binding to the surfaces of viable C. albicans filaments. Eight distinct phage clones that bound specifically to filament surface antigens not expressed on blastoconidia were identified. Single-chain antibody variable fragments (scFv) derived from two of these phage clones (scFv5 and scFv12) were characterized in detail. Filament-specific antigen expression was detected by an indirect immunofluorescence assay. ScFv5 reacted with C. dubliniensis filaments, while scFv12 did not. Neither scFv reacted with C. glabrata, C. parapsilosis, C. rugosa, C. tropicalis, or Saccharomyces cerevisiae grown under conditions that stimulated filament formation in C. albicans and C. dubliniensis. Epitope detection by the two scFv was sensitive to proteinase K treatment but not to periodate treatment, indicating that the cognate epitopes were composed of protein. The antigens reactive with scFv5 and scFv12 were extractable from the cell surface with Zymolyase, but not with sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and 2-mercaptoethanol, and migrated as polydisperse, high-molecular-weight bands on SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gels. The epitopes were detected on clinical specimens obtained from infants with thrush and urinary candidiasis without passage of the organisms on laboratory media, confirming epitope expression in human infection. The availability of a monoclonal immunologic reagent that recognizes filaments from both C. albicans and C. dubliniensis and another specific only to C. albicans adds to the repertoire of potential diagnostic reagents for differentiation between these closely related species.

Candida albicans is a pathogenic fungus of humans that continues to be of considerable medical importance. C. albicans may infect both skin and mucous membranes, and it is also capable of causing life-threatening systemic infections, particularly in the immunocompromised host (7, 35). A number of putative virulence factors have been proposed for C. albicans and have garnered experimental support (7, 13). Among these, the ability of the organism to convert morphogenically from blastoconidia to filamentous forms has been the subject of intensive study (7). C. albicans and C. dubliniensis are unique within the genus in that, in addition to the pseudohyphal form, they also form germ tubes and true hyphae (7). Like blastoconidia, pseudohyphae form by budding; however, the new cell remains attached to the parent and elongates with constrictions where cells meet. In contrast, germ tubes are outgrowths of the blastoconidia that grow by apical extension and form septae behind the growing tip. The germ tube is the precursor to the true hypha, with parallel wall morphology. The conversion to hyphae is accompanied by expression of novel antigens on the filamentous form, identified by using both polyclonal sera and monoclonal antibodies (5, 8-12, 14, 18, 25, 28, 31, 37, 39-41, 43, 49-53).

The expansion of medical technology and the increased survival of immunocompromised patients has led to a general increase in mycoses over the past several decades (15, 21). Although C. albicans remains the most virulent Candida species, infections caused by other species, including C. tropicalis, C. glabrata, and C. parapsilosis, have increased in relative prevalence (33). C. dubliniensis, a species closely related to C. albicans in both phenotype and genotype, was first described in 1995, when it was associated with oral infection in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (48). This organism has since been described across diverse geographic regions and has been associated with both superficial and systemic infections (33). Because of its similarities to C. albicans, particularly its ability to form filaments, differentiating C. albicans from C. dubliniensis has been challenging. A variety of phenotypic assays have been employed, but none have proven completely reliable (47). Growth of C. dubliniensis is inhibited at 45°C, but this method requires several days' growth on synthetic media (38). The most accurate methods currently available for differentiating these species are molecular techniques such as PCR, DNA fingerprinting, and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, but these are time-consuming and difficult to apply to large numbers of isolates (47). A novel approach using fluorescent in situ hybridization with peptide nucleic acid probes (PNA-FISH) to detect differences in the rRNA sequences between these species has been reported and holds promise (36). Other recent efforts have been made to exploit serologic differences between these two species, with some success (3, 28, 32), offering the potential for immunologic reagents to provide more efficient and rapid identification.

We have been using phage display technology to study surface antigen expression on C. albicans (17). In the present study, we have applied this technology to identify single-chain antibody fragments (scFv) that specifically recognize the filamentous form of C. albicans. This technique allows for the rapid isolation of monoclonal, human immunologic reagents with which to study the differential surface expression of Candida antigens during morphogenesis, and it has yielded reagents that can distinguish C. albicans from C. dubliniensis, as shown in the present study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Organisms.

Fungal strains used in this study are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Fungal strains, their filamentation phenotypes in Medium 199 or in serum, and their reactivities in both by IFA with scFv5 and scFv12

| Species | Strain name | Filament phenotype in:

|

Reactivity

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M199 | Serum | scFv5 | scFv12 | ||

| Candida albicans | Ca3153A,a Ca613p,b MRO2-O,c MRO4-O, MRO9-R, MRO17-O, SC5314, CAH7-1Ad | + | +g | + | + |

| Candida dubliniensis | CBS7987,e CBS7988, CBS8500 | + | + | + | − |

| Candida glabrata | MRO84-R | − | − | − | − |

| Candida parapsilosis | RO75-R1 | − | − | − | − |

| Candida rugosa | MRO63-V | + | + | − | − |

| Candida tropicalis | MRO84-O | − | − | − | − |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | T481f | − | NDh | − | − |

Ca3153A (27, 34, 42, 54) was used as the strain for panning of the recombinant human scFv phage library and was kindly provided by E. Rustchenko, Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics, University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry, Rochester, N.Y.

Strains designated “MRO” or “RO” were collected as part of a prospective study of Candida colonization in mothers and neonates at Strong Memorial Hospital, Rochester, N.Y., and were kindly provided by W. Watson, formerly of the Department of Pediatrics, University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry.

C. albicans strains CAH7-1A (hwp1/hwp1) and SC5314 (wild type) were kindly provided by P. Sundstrom, Ohio State University, Columbus (44).

C. dubliniensis strains were purchased from the Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures, Utrecht, The Netherlands, and were kindly provided by S. Spinelli, Department of Chemistry, University of Rochester, Rochester, N.Y.

T481 was kindly provided by J. S. Butler, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry.

C. albicans strains grown in serum had a more pleiomorphic appearance than when grown in Medium 199, but they retained their activity with the scFv.

ND, not determined.

Identification and enrichment of C. albicans-binding scFv phage by successive rounds of panning on intact cells.

C. albicans strain 3153A was used as the starting strain for panning the phage library (17). To isolate scFv against determinants expressed on the filament of C. albicans, a culture was grown overnight on a shaker platform at 37°C in liquid yeast extract-peptone-dextrose (YEPD) medium (Difco, Detroit, Mich.) with vigorous aeration (225 rpm) to stationary phase (∼2 × 108 cells/ml). Cells were diluted in Medium 199 (supplemented with Earle’s balanced salt solution, HEPES, and glutamine; BioWhittaker, Walkersville, Md.) to 105 cells/ml in 96-well flat-bottom tissue culture plates and were grown at 37° for 4 h. Filament growth was confirmed by light microscopy. The medium was removed, and wells were blocked with 0.5% casein in Tris-buffered saline (pH 7.5) (TBS) at room temperature for 1 h. We have previously described the construction of a large naïve human antibody library in a M13 phage display format (17). Approximately 5 × 1010 phage from the library were added to each well and incubated at room temperature for 90 min with gentle mixing on a rotator platform. Wells were washed extensively with TBS containing 0.5% Tween 20, followed by two brief washes with water to remove detergent. Bound phage were eluted by incubation with 0.1 M glycine (pH 2.2) containing 1 mg of bovine serum albumin (BSA)/ml for 15 min and were transduced into Escherichia coli strain TG1. Ampicillin-resistant transductants were regrown and infected with helper phage for a subsequent round of enrichment.

Populations of phage that exhibited increased binding to the C. albicans filaments after two rounds of enrichment were analyzed for sequence diversity by PCR and restriction enzyme digestion. The scFv coding sequence was amplified by using primers that flank the cloning sites followed by restriction digestion with BstNI. Clones that had distinct restriction patterns were chosen for further analysis. The clones of interest were then manipulated to remove the M13 gene III fragment, and mature scFv containing the FLAG epitope at the amino terminus and the hexahistidine tag at the carboxy terminus were prepared as described previously (17).

IFA detection of binding of phage or scFv protein to Candida strains.

Blastoconidia of Candida strains were induced to form filaments via inoculation at 5 × 105 cells/ml either in Medium 199 in six-well culture dishes on the surfaces of glass coverslips or in human serum in 24-well culture dishes on the surfaces of plastic coverslips (35). Cells were incubated at 37°C for 3 to 4 h, and the filamentous phenotype was determined by light microscopy (Table 1). Coverslips were allowed to air dry, rinsed briefly with water, and blocked with 3% BSA (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 30 min. The blocking solution was replaced with 3% BSA containing either 1012 CFU of individual M13 phage clones/ml or 10 μg of a scFv/ml. After a 2-h incubation at room temperature (RT), the coverslips were washed extensively in PBS and incubated either in 10 μg of a biotinylated sheep polyclonal secondary antibody specific for M13 phage (5 Prime→3 Prime, Inc., Boulder, Colo.)/ml for the phage indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA) or in 10 μg of a monoclonal antibody (M2) specific for the FLAG epitope tag at the amino terminus of the scFv (catalog no. F3165; Sigma)/ml for the scFv IFA, followed by the appropriate tertiary streptavidin-fluorescein or antibody-fluorescein conjugate (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, Pa.). Specimens were allowed to air dry and were viewed by using fluorescence microscopy.

Biochemical analysis of C. albicans antigens recognized by scFv.

Organisms were grown on coverslips as described above for IFA. Coverslips were then treated either with proteinase K or trypsin to degrade proteinaceous antigens or with sodium periodate to degrade carbohydrate antigens on the cell surface. For proteinase K, coverslips were first incubated in 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5) containing 100 μg of proteinase K/ml for 2 h at 37°C and then washed with water (23). For trypsin, coverslips were first incubated in 0.05% trypsin-0.53 mM EDTA · 4Na in Hanks balanced salt solution (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) for 2 h at 37°C and then washed with water. For sodium periodate treatment, coverslips were first incubated in 50 mM sodium acetate (pH 4.5) containing 50 mM sodium periodate for 30 min at 4°C in the dark and then washed with water. Mock-treated samples were incubated in the respective buffer alone. Adherent cells were then analyzed by IFA as described above. To confirm that loss of binding via scFv was not due to degradation of scFv via residual proteinase activity, blastoconidia of C. albicans 3153A were used as a control in proteinase K experiments and were analyzed via IFA with scFv λ2-18. This scFv has previously been shown to recognize a carbohydrate antigen (17).

IFA detection of binding of scFv protein to Candida in clinical specimens.

Patients identified as having potential Candida infections in either the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit or the Pediatric Hematology/Oncology outpatient service at the Golisano Children's Hospital at Strong in Rochester, N.Y., were referred to one of the authors (J.M.B.). Referrals were obtained for three infants with oropharyngeal candidiasis (thrush) and one infant with urinary candidiasis. Informed consent was obtained from the parents of each subject. Oropharyngeal specimens were collected with a moistened, sterile cotton swab. The urine specimen was collected from a spontaneous void and centrifuged to collect sediment. Immediately after collection, specimens were spread directly on microscope slides and allowed to dry. IFAs with scFv were performed as described above. The specimen collection protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Rochester, Rochester, N.Y.

Antigen extraction from C. albicans filaments.

C. albicans 3153A filaments were prepared by inoculation of 100 ml of Medium 199 with organisms at 106 cells/ml, followed by growth at 37°C for 3 to 4 h. Filamentous forms were collected by centrifugation, washed with water, and stored at −20°C until use. Antigens were extracted by using either sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) or Zymolyase. For SDS extraction, filaments were combined in a 1:1 ratio (wet weight to volume) with 2× SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) cracking buffer (Novex, Carlsbad, Calif.) in the presence or absence of 5% 2-mercaptoethanol and then boiled for 10 min. For Zymolyase treatment, a modification of the method described by Sundstrom and Kenny was utilized (50). Briefly, filaments were treated with 1 mg of Zymolyase/ml in 100 mM Tris (pH 8.0)-500 mM MgSO4 · 7H2O-1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride at 30°C for 2 h. Extracts were centrifuged briefly to remove particulate matter, and supernatants were dialyzed overnight against 10 mM Tris (pH 8.0)-50 mM MgSO4 · 7H2O and concentrated by lyophilization. Concentrated extracts were loaded onto an SDS-4-to-20% polyacrylamide gel (Novex) and electrophoresed for 2 h at 125 V. Extracts were electrotransferred to nitrocellulose filters and blocked for 30 min at RT with 5% dried skim-milk in PBS (Blotto). Respective scFv were diluted to 10 μg/ml in 5% Blotto, and the filters were probed overnight at RT. Anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody M2 (Sigma) at 10 μg/ml and alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (Jackson ImmunoResearch) were used as secondary and tertiary reagents, respectively.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The GenBank accession numbers for scFv5 and scFv12 are AY143558 and AY143559, respectively.

RESULTS

Enrichment of C. albicans-binding scFv phage by successive rounds of panning on intact cells.

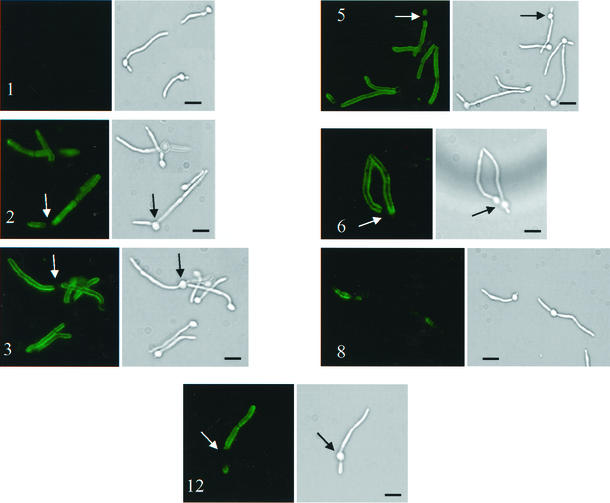

A phage display library expressing scFv of human immunoglobulin has been described previously (17). The phage display library was panned against whole cells. After two rounds of panning, 100-fold enrichment was observed. From 16 clones examined by restriction digestion following the second round of panning, 9 distinct restriction patterns were observed. A phage IFA was performed with each of these nine clones. Eight of the nine were positive for binding to C. albicans by phage IFA (Fig. 1). Clone 1 did not bind and was included as a negative control. Five clones stained the filament specifically and uniformly (Fig. 1, clones 2, 3, 5, 6, and 12), while three gave a speckled and nonuniform pattern of staining (clone 8 [Fig. 1] and clones 4 and 11 [data not shown]). Two clones, scFv5 and scFv12, which showed the strongest uniform staining of the filament via phage IFA, were selected for further study. They were each converted to express scFv protein as described previously (17) to facilitate further analysis.

FIG. 1.

IFA detection of binding of phage clones to C. albicans. Representative fields are shown. Paired panels are immunofluorescent and bright-field photomicrographs of the same microscopic fields of C. albicans strain 3153A stained via IFA with representative M13 phage clones displaying scFv. Numbers identify the clone from the original 16. Clone 1 did not bind and was included as a negative control. Arrows point to blastoconidia that were not stained by phage IFA. Bars, 10 μm.

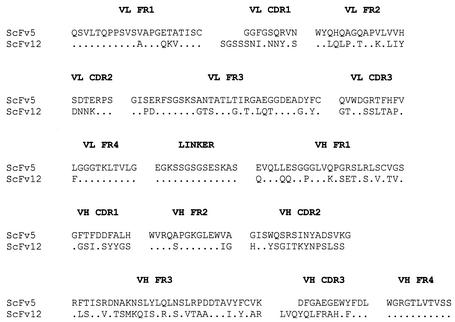

The nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of the VL and VH regions of scFv5 and scFv12 were determined. Deduced amino acid sequences are shown in Fig. 2. The VL regions of both scFv5 and scFv12 were of the lambda family. The VH region of scFv5 was of the VH3 family, and that of scFv12 belonged to the VH4 family (22). Substantial differences were observed in the complementarity-determining regions (CDRs) of scFv5 and scFv12 in both the VL and VH chains, suggesting that the two antibody fragments did not recognize the same epitope on Candida filaments.

FIG. 2.

Comparison of the deduced amino acid sequences of scFv5 and scFv12. The cloning strategy yields a VL-linker-VH orientation of the scFv. The framework (FR) and CDRs as defined by Kabat et al. (22) are indicated. The position and sequence of the linker between the VL and VH regions are also shown. A dot indicates amino acid identity at a given position in scFv12 to the corresponding residue in scFv5.

IFA of scFv5 and scFv12 against species of Candida.

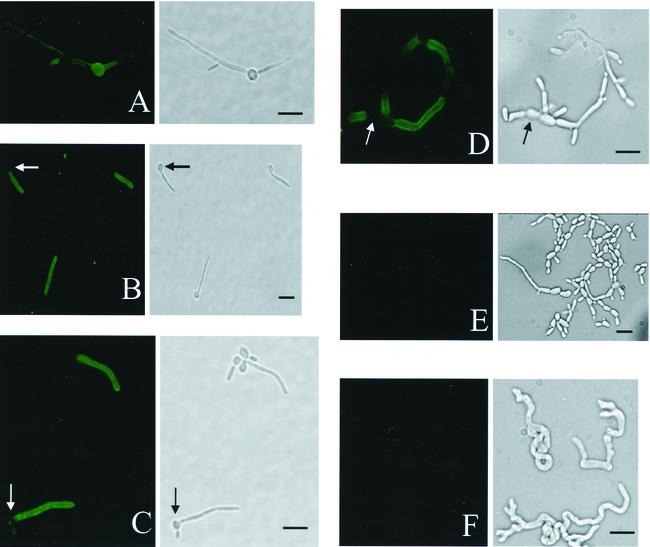

The filamentation phenotypes of the strains used in this study when grown in Medium 199 (see Materials and Methods) are shown in Table 1, as are their reactivities with scFv5 and scFv12 by IFA. The photomicrographs in Fig. 3 show scFv binding by IFA to Candida species that formed filaments: C. albicans strain 3153A (Fig. 3A through C), C. dubliniensis strain CBS7987 (Fig. 3D and E), and C. rugosa strain MRO63-V (Fig. 3F). Figure 3A shows a previously described scFv, λ2-18 (17), binding primarily to the parent blastoconidia of the fungus. Figure 3B and C show scFv5 and scFv12, respectively, binding exclusively to the filamentous portion of the cell while sparing the parent blastoconidia. This pattern is consistent with that seen in the phage IFA. Figure 3D shows scFv5 binding to filamentous portions of C. dubliniensis. In contrast to scFv5, scFv12 showed no fluorescence in an IFA with C. dubliniensis (Fig. 3E). This differential pattern of fluorescence was consistent in all three C. dubliniensis strains examined. An independent experiment using phage from clones 5 and 12 in an IFA with C. dubliniensis confirmed this difference in antigen recognition (data not shown). Neither scFv5 nor scFv12 bound to other species tested in these assays (Table 1). C. rugosa was unique among the other species tested in that it formed filaments under the growth conditions used but showed no reactivity with either scFv clone (Fig. 3F; Table 1). To confirm that the same patterns of antigen expression would be obtained when filament growth was induced by human serum, the IFA was repeated with cells grown in serum rather than Medium 199. The same pattern of antigen expression was observed under these conditions (Table 1).

FIG. 3.

IFA detection of binding of scFv5 and scFv12 to Candida species. Paired panels are immunofluorescent and bright-field photomicrographs of the same microscopic fields. (A) scFv λ2-18 binding to C. albicans, showing the highest intensity for binding to the blastoconidia as previously described (17). (B, D, and F) scFv5 binding to C. albicans (B), C. dubliniensis (D), and C. rugosa (F). C. albicans and C. dubliniensis stained intensely, while C. rugosa was negative. (C and E) scFv12 binding to C. albicans (C) and C. dubliniensis (E). scFv12 stained only C. albicans. Arrows indicate blastoconidia that did not stain. Bars, 10 μm.

The patterns of binding by scFv5 and svFv12 depicted in Fig. 3B and C, respectively, are representative of many independent experiments with multiple strains of C. albicans (Table 1). The scFv bound to the filament uniformly and to virtually all the individual cells in a given IFA. The antigens could be detected on very small, nascent filaments and were also detected in uniform distribution on mature filaments grown over 24 h. These observations suggest that the cognate antigens are expressed early in the process of filamentation and persist throughout filament growth.

Biochemical analysis of antigens recognized by scFv5 and scFv12.

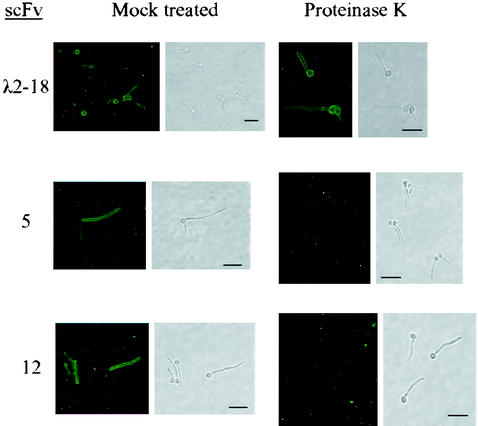

To determine whether the cognate antigens recognized by scFv5 and scFv12 were composed of carbohydrate or protein, C. albicans cells were grown on coverslips in Medium 199 to promote filament growth. Cells were dried and then treated either with proteinase K or trypsin, to degrade protein, or with sodium periodate, to degrade carbohydrate structures. Cells were then analyzed by an IFA with scFv5 or scFv12. The proteolytic activity of proteinase K was confirmed by degradation of BSA (data not shown). Cells treated with proteinase K lost their reactivity with the scFv (Fig. 4), while those treated with periodate maintained the same fluorescence as cells treated with acetate buffer alone (data not shown). These results suggest that the cognate antigen for both scFv5 and scFv12 was protein. An IFA with λ2-18, previously reported to recognize a periodate-sensitive epitope (17), was included as a control. As expected, λ2-18 scFv binding was maintained following proteinase K treatment (Fig. 4) but was lost following periodate treatment (data not shown), demonstrating that the proteinase K treatment did not interfere with scFv binding to the cell surface and that the periodate treatment was effective in degrading carbohydrate surface antigens. Cells treated with trypsin also lost fluorescence by IFA, providing additional support for the proteinaceous nature of the epitopes (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

IFA detection of scFv5 and scFv12 binding to C. albicans after proteinase K treatment. Paired panels are immunofluorescent and bright-field photomicrographs of the same microscopic fields. C. albicans filaments were subjected to proteinase K digestion, and the presence of antigen was detected by IFA. Mock-treated cells were treated with buffer alone. scFv λ2-18 has previously been shown to recognize a carbohydrate epitope (17) and was included as a control. Proteinase K eliminated binding by scFv5 and scFv12. Bars, 15 μm.

IFA of scFv5 and scFv12 against C. albicans clinical isolates.

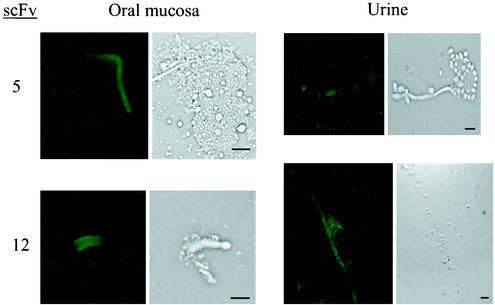

To confirm that the antigens recognized by scFv5 and scFv12 were expressed in actual human infection, Candida specimens were obtained from infants with oropharyngeal candidiasis or with urinary tract infections with Candida. These specimens were obtained and processed as described in Materials and Methods. An IFA was performed on the primary patient specimens. Figure 5 shows representative fields from the IFA with both scFv against specimens obtained from both sites. An IFA with no added scFv was performed in parallel as a negative control and showed no fluorescence (data not shown). These data confirm that the cognate antigens recognized by scFv5 and scFv12 are expressed in human infection.

FIG. 5.

IFA detection of scFv5 and scFv12 binding to C. albicans in clinical samples. Paired panels are immunofluorescent and bright-field photomicrographs of the same microscopic fields. Clinical specimens were collected from infants with thrush (oral mucosa) or urinary candidiasis (urine) and spread immediately on microscope slides. Binding of scFv5 and scFv12 was detected by IFA. Bars, 10 μm.

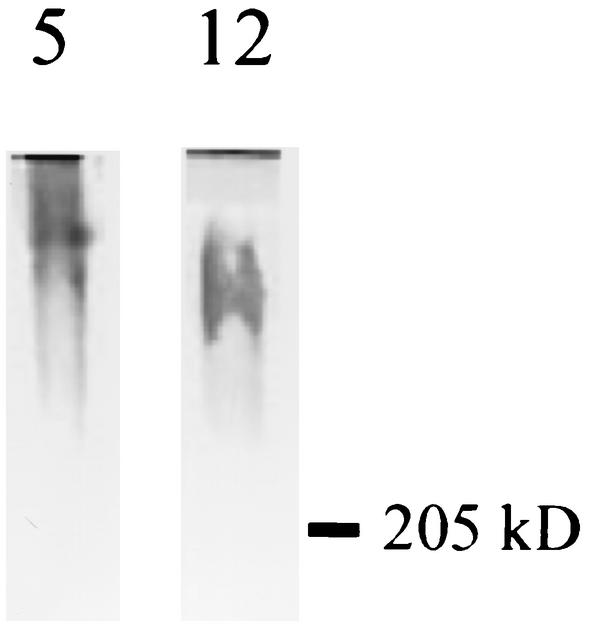

Western blotting of extracted antigens from C. albicans with scFv5 and scFv12.

C. albicans was grown in Medium 199 to allow filamentation, and filaments were collected by centrifugation. They were then extracted by boiling in the presence of SDS with or without 2-mercaptoethanol or, alternatively, by digestion with Zymolyase. Extracts were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose filters, and probed with scFv5 or scFv12. No antigen was detected in the SDS extracts despite several attempts (data not shown). Antigen was detected by both scFv as a disperse, high-molecular-weight band in the Zymolyase-extracted samples (Fig. 6). Although not extractable by SDS and 2-mercaptoethanol, the antigen is apparently stable in their presence, as the immunoblots showed reactivity despite being separated by SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions.

FIG. 6.

Western blotting of C. albicans antigens by using scFv5 and scFv12. C. albicans filaments were extracted with Zymolyase, and extracts were separated by SDS-PAGE (4 to 20% polyacrylamide), transferred to nitrocellulose filters, and probed with scFv. A polydisperse, high-molecular-weight band was detected with each scFv clone (5, scFv5; 12, scFv12). The position of the 205-kDa molecular size marker is indicated.

DISCUSSION

We have used a combinatorial phage display library expressing single-chain, variable light (VL), and variable heavy (VH) human immunoglobulin fragments to identify phage clones capable of binding to the filamentous forms of live C. albicans. After two rounds of enrichment, 16 clones were investigated; they yielded 9 unique scFv based on restriction length polymorphisms. The advantage of using live cells in the panning process is that it increases the likelihood of obtaining scFv reactive with surface components exposed to the external environment. The high level of diversity among these 16 clones may reflect the antigenic complexity of the filament surface. Further, since human lymphocytes were the source of the variable-region genes used to construct the library (26), the “immunologic history” of the individuals from whom the lymphocytes were obtained will contribute to the specificities available in the library. The diversity of clones obtained supports a complex interplay between host and microbe and may reflect a role for these surface antigens in host immune interactions.

Two scFv clones that showed uniform and bright fluorescence of filaments, both germ tubes and hyphae, by IFA were selected for further study. These clones, scFv5 and scFv12, bound the entire population of cells in a given experiment and showed binding to the entire filament length in true hyphae after 24 h of incubation (data not shown). Although the patterns of binding of these two scFv to C. albicans by IFA were very similar, scFv5 recognizes an epitope present on the filaments of C. dubliniensis while scFv12 does not. Although these species are morphologically and genetically similar, antigenic differences on their surfaces have been documented by adsorption of a polyclonal C. dubliniensis antiserum with C. albicans blastoconidia (2). Interestingly, although there were clear differences between the antigenic profiles of extracts from these two species, this antiserum recognized an epitope on C. albicans germ tubes, and adsorption of the serum with C. albicans germ tubes eliminated binding to C. dubliniensis. Differences in antigen recognition by use of sera from experimentally induced infections with these two species have also been documented (32). To our knowledge, there is a single report of a monoclonal antibody that binds C. albicans but not C. dubliniensis, and the usefulness of this antibody for diagnostic differentiation between these closely related species has been proposed (28). Our finding of a phage clone that recognizes an antigen shared by the filamentous forms of these two species constitutes the first description of a monoclonal immunologic reagent that has this property. Further, its specificity for filaments and the absence of binding to other Candida species make it a candidate for use as a diagnostic reagent. By using the two scFv together, one could envision a parallel test for identification of filamentous Candida in which one reagent would be positive for both C. albicans and C. dubliniensis (scFv5), while the other would be positive for C. albicans and negative for C. dubliniensis (scFv12). Such a test would provide an internal control for the validity of the result.

We have confirmed the expression of the scFv cognate antigens in actual human infection with specimens obtained from infants with thrush or urinary candidiasis tested without prior growth on laboratory media. These reagents thus provide the flexibility to identify organisms in direct clinical samples by IFA, which we used successfully in this study, or by immunohistochemistry. This obviates the need for incubation on laboratory media and leads to more-rapid identification. Further, an IFA used as a diagnostic tool to distinguish C. dubliniensis from C. albicans is preferable to many of the phenotype-based or molecular methods currently available in that it affords ease of use, rapidity, reliability, affordability, and the ability to be applied to a large number of samples. These properties are essential for epidemiologic studies, which are needed to further define the clinical importance of this recently identified species (47). The observation that C. dubliniensis rapidly develops fluconazole resistance in vitro may provide additional clinical relevance to such epidemiologic studies and underscores the importance of reagents that can identify this organism rapidly and efficiently (47).

Although the scFv described in this study detect antigens expressed only on filaments and do not detect other Candida species aside from C. albicans and C. dubliniensis, we have previously described scFv that were raised against C. albicans blastoconidia (17). These scFv detected carbohydrate antigens expressed on many Candida species. By using these scFv in combination, one could tailor the specificities for detection of Candida as appropriate for a given application, be it distinction between C. albicans and C. dubliniensis, detection of yeast forms versus hyphae in specimens, or detection of Candida species versus other pathogenic fungi.

Many Candida filament antigens characterized to date are extractable under reducing conditions and with Zymolyase (29, 40, 43, 50). The cognate antigens of scFv5 and scFv12 were not extractable with 2-mercaptoethanol and SDS despite multiple attempts. The antigens are stable under these conditions, however, as they are detectable by Western blotting after separation by SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions. Their sensitivity to proteinase K, but not to periodate, confirms the proteinaceous nature of the antigens and is also typical of antigens unique to the filamentous forms (49). The antigens were extractable by Zymolyase treatment and ran as polydisperse bands of high molecular weight. This pattern may reflect glycosylation of the antigens. Despite their similarities, the notion that scFv5 and scFv12 recognize distinct antigens is supported by several observations: (i) they have unique aspects to their coding sequences; (ii) the VH regions of scFv5 and scFv12 are of distinct families; (iii) scFv5 recognizes an epitope expressed on C. dubliniensis while scFv12 does not; and (iv) the mobilities of the cognate antigens in Zymolyase extracts are different. However, the possibility that they recognize distinct epitopes of the same protein remains a reasonable alternative.

To date, six hypha-specific genes have been identified and characterized in C. albicans (6). These include ALS3/ALS8 (19, 20), ECE1 (4), HWP1 (45, 46), HYR1 (1), and CSA1 (24). All except ECE1 appear to encode cell surface proteins. None of these gene products are required for filamentous growth, however, as evidenced by the fact that mutations in these loci do not result in a morphological defect in hyphal development. Hwp1 has been the most extensively characterized and is a cell surface exposed mannoprotein that is developmentally regulated and expressed in germ tubes and true hyphae of C. albicans (44). This protein serves as a substrate for mammalian transglutaminases and is important for adhesion to epithelial cells. We have confirmed that the cognate antigens of scFv5 and scFv12 are distinct from Hwp1, as they both bind filaments of the hwp1/hwp1 knockout strain CAH7-1A (44) (Table 1). The possibility that the antigens recognized by the scFv clones represent one of the other cloned gene products remains and awaits further analysis. However, Csa1 is extractable with dithiothreitol and is unlike the scFv-reactive antigens in that respect, as they were not extractable under reducing conditions.

The use of phage display technology to identify antigens unique to the filamentous forms of C. albicans is a simple and rapid method that can further our understanding of antigen expression by this medically important and complex fungus. The antibody fragments identified are useful tools for studying the antigenic variation of C. albicans. This technology also has the potential to identify structural proteins of the germ tube that are required for hyphal growth and that have not been described to date. We have already demonstrated a potential diagnostic use for the reagents developed in these studies that has both clinical and research applications. Further, since the scFv are entirely human, they may, if converted to mature antibody forms, also provide a therapeutic benefit as agents for passive immunization. Studies are under way to identify the genes encoding the antigens recognized by these scFv and should allow a better understanding of the antigenic complexity of the Candida cell wall.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Paula Sundstrom for providing the hwp1/hwp1 strain CAH17-1A. We thank Carl D'Angio and Frank Gigliotti for critical review of the manuscript.

J.M.B. was supported by National Institutes of Health grant T32 AI07464.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bailey, D. A., P. J. Feldmann, M. Bovey, N. A. Gow, and A. J. Brown. 1996. The Candida albicans HYR1 gene, which is activated in response to hyphal development, belongs to a gene family encoding yeast cell wall proteins. J. Bacteriol. 178:5353-5360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bikandi, J., R. S. Millan, M. D. Moragues, G. Cebas, M. Clarke, D. C. Coleman, D. J. Sullivan, G. Quindos, and J. Ponton. 1998. Rapid identification of Candida dubliniensis by indirect immunofluorescence based on differential localization of antigens on C. dubliniensis blastospores and Candida albicans germ tubes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:2428-2433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bikandi, J., R. San Millan, P. Regulez, M. D. Moragues, G. Quindos, and J. Ponton. 1998. Detection of antibodies to Candida albicans germ tubes during experimental infections by different Candida species. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 5:369-374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birse, C. E., M. Y. Irwin, W. A. Fonzi, and P. S. Sypherd. 1993. Cloning and characterization of ECE1, a gene expressed in association with cell elongation of the dimorphic pathogen Candida albicans. Infect. Immun. 61:3648-3655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brawner, D. L., and J. E. Cutler. 1986. Variability in expression of cell surface antigens of Candida albicans during morphogenesis. Infect. Immun. 51:337-343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown, A. J. 2002. Expression of growth form-specific factors during morphogenesis in Candida albicans, p. 87-93. In R. A. Calderone (ed.), Candida and candidiasis. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 7.Calderone, R. A. (ed.). 2002. Candida and candidiasis. ASM Press, Washington D.C.

- 8.Casanova, M., M. L. Gil, L. Cardenoso, J. P. Martinez, and R. Sentandreu. 1989. Identification of wall-specific antigens synthesized during germ tube formation by Candida albicans. Infect. Immun. 57:262-271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Casanova, M., J. P. Martinez, and W. L. Chaffin. 1991. Identification of germ tube cell wall antigens of Candida albicans. J. Med. Vet. Mycol. 29:269-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chaffin, W. L., J. Skudlarek, and K. J. Morrow. 1988. Variable expression of a surface determinant during proliferation of Candida albicans. Infect. Immun. 56:302-309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chardes, T., M. Piechaczyk, V. Cavailles, S. L. Salhi, B. Pau, and J. M. Bastide. 1986. Production and partial characterization of anti-Candida monoclonal antibodies. Ann. Inst. Pasteur. Immunol. 137C:117-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chaturvedi, V. P., R. Vanegas, and W. L. Chaffin. 1994. Coordination of germ tube formation and surface antigen expression in Candida albicans. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 124:99-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cutler, J. E. 1991. Putative virulence factors of Candida albicans. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 45:187-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deslauriers, N., J. Michaud, B. Carre, and C. Leveillee. 1996. Dynamic expression of cell-surface antigens probed with Candida albicans-specific monoclonal antibodies. Microbiology 142:1239-1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fridkin, S. K., and W. R. Jarvis. 1996. Epidemiology of nosocomial fungal infections. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 9:499-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaspari, A. A., R. Burns, A. Nasir, D. Ramirez, R. K. Barth, and C. G. Haidaris. 1998. CD86 (B7-2), but not CD80 (B7-1), expression in the epidermis of transgenic mice enhances the immunogenicity of primary cutaneous Candida albicans infections. Infect. Immun. 66:4440-4449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haidaris, C. G., J. Malone, L. A. Sherrill, J. M. Bliss, A. A. Gaspari, R. A. Insel, and M. A. Sullivan. 2001. Recombinant human antibody single chain variable fragments reactive with Candida albicans surface antigens. J. Immunol. Methods 257:185-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hopwood, V., D. Poulain, B. Fortier, G. Evans, and A. Vernes. 1986. A monoclonal antibody to a cell wall component of Candida albicans. Infect. Immun. 54:222-227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoyer, L. L. 2001. The ALS gene family of Candida albicans. Trends Microbiol. 9:176-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoyer, L. L., T. L. Payne, M. Bell, A. M. Myers, and S. Scherer. 1998. Candida albicans ALS3 and insights into the nature of the ALS gene family. Curr. Genet. 33:451-459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jarvis, W. R. 1995. Epidemiology of nosocomial fungal infections, with emphasis on Candida species. Clin. Infect. Dis. 20:1526-1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kabat, E. A., T. T. Wu, H. Perry, K. Gottesman, and C. Foeller. 1991. Sequences of proteins of immunological interest, 5th ed. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md.

- 23.Kanbe, T., Y. Han, B. Redgrave, M. H. Riesselman, and J. E. Cutler. 1993. Evidence that mannans of Candida albicans are responsible for adherence of yeast forms to spleen and lymph node tissue. Infect. Immun. 61:2578-2584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lamarre, C., N. Deslauriers, and Y. Bourbonnais. 2000. Expression cloning of the Candida albicans CSA1 gene encoding a mycelial surface antigen by sorting of Saccharomyces cerevisiae transformants with monoclonal antibody-coated magnetic beads. Mol. Microbiol. 35:444-453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li, R. K., and J. E. Cutler. 1991. A cell surface/plasma membrane antigen of Candida albicans. J. Gen. Microbiol. 137:455-464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Malone, J., and M. A. Sullivan. 1996. Analysis of antibody selection by phage display utilizing anti-phenobarbital antibodies. J. Mol. Recognit. 9:738-745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manavathu, M., S. Gunasekaran, Q. Porte, E. Manavathu, and M. Gunasekaran. 1996. Changes in glutathione metabolic enzymes during yeast-to-mycelium conversion of Candida albicans. Can. J. Microbiol. 42:76-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marot-Leblond, A., L. Grimaud, S. Nail, S. Bouterige, V. Apaire-Marchais, D. J. Sullivan, and R. Robert. 2000. New monoclonal antibody specific for Candida albicans germ tube. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:61-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marot-Leblond, A., R. Robert, J. M. Senet, and T. Palmer. 1995. Purification of a Candida albicans germ tube specific antigen. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 12:127-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meitner, S. W., W. H. Bowen, and C. G. Haidaris. 1990. Oral and esophageal Candida albicans infection in hyposalivatory rats. Infect. Immun. 58:2228-2236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Merson-Davies, L. A., V. Hopwood, R. Robert, A. Marot-Leblond, J. M. Senet, and F. C. Odds. 1991. Reaction of Candida albicans cells of different morphology index with monoclonal antibodies specific for the hyphal form. J. Med. Microbiol. 35:321-324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moragues, M. D., M. J. Omaetxebarria, N. Elguezabal, J. Bikandi, G. Quindos, D. C. Coleman, and J. Ponton. 2001. Serological differentiation of experimentally induced Candida dubliniensis and Candida albicans infections. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:2999-3001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moran, G. P., D. J. Sullivan, and D. C. Coleman. 2002. Emergence of non-Candida albicans Candida species as pathogens, p. 37-53. In R. A. Calderone (ed.), Candida and candidiasis. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 34.Morrow, B., H. Ramsey, and D. R. Soll. 1994. Regulation of phase-specific genes in the more general switching system of Candida albicans strain 3153A. J. Med. Vet. Mycol. 32:287-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Odds, F. C. 1988. Candida and candidosis, 2nd ed. Balliere Tindall, London, England.

- 36.Oliveira, K., G. Haase, C. Kurtzman, J. J. Hyldig-Nielsen, and H. Stender. 2001. Differentiation of Candida albicans and Candida dubliniensis by fluorescent in situ hybridization with peptide nucleic acid probes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:4138-4141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ollert, M. W., and R. A. Calderone. 1990. A monoclonal antibody that defines a surface antigen on Candida albicans hyphae cross-reacts with yeast cell protoplasts. Infect. Immun. 58:625-631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pinjon, E., D. Sullivan, I. Salkin, D. Shanley, and D. Coleman. 1998. Simple, inexpensive, reliable method for differentiation of Candida dubliniensis from Candida albicans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:2093-2095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ponton, J., and J. M. Jones. 1986. Identification of two germ-tube-specific cell wall antigens of Candida albicans. Infect. Immun. 54:864-868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ponton, J., A. Marot-Leblond, P. A. Ezkurra, B. Barturen, R. Robert, and J. M. Senet. 1993. Characterization of Candida albicans cell wall antigens with monoclonal antibodies. Infect. Immun. 61:4842-4847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Quindos, G., J. Ponton, and R. Cisterna. 1987. Detection of antibodies to Candida albicans germ tube in the diagnosis of systemic candidiasis. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. 6:142-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rustchenko, E. P., D. H. Howard, and F. Sherman. 1997. Variation in assimilating functions occurs in spontaneous Candida albicans mutants having chromosomal alterations. Microbiology 143:1765-1778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smail, E. H., and J. M. Jones. 1984. Demonstration and solubilization of antigens expressed primarily on the surfaces of Candida albicans germ tubes. Infect. Immun. 45:74-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Staab, J. F., S. D. Bradway, P. L. Fidel, and P. Sundstrom. 1999. Adhesive and mammalian transglutaminase substrate properties of Candida albicans Hwp1. Science 283:1535-1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Staab, J. F., C. A. Ferrer, and P. Sundstrom. 1996. Developmental expression of a tandemly repeated, proline-and glutamine-rich amino acid motif on hyphal surfaces on Candida albicans. J. Biol. Chem. 271:6298-6305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Staab, J. F., and P. Sundstrom. 1998. Genetic organization and sequence analysis of the hypha-specific cell wall protein gene HWP1 of Candida albicans. Yeast 14:681-686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sullivan, D., and D. Coleman. 1998. Candida dubliniensis: characteristics and identification. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:329-334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sullivan, D. J., T. J. Westerneng, K. A. Haynes, D. E. Bennett, and D. C. Coleman. 1995. Candida dubliniensis sp. nov.: phenotypic and molecular characterization of a novel species associated with oral candidosis in HIV-infected individuals. Microbiology 141:1507-1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sundstrom, P. M., and G. E. Kenny. 1984. Characterization of antigens specific to the surface of germ tubes of Candida albicans by immunofluorescence. Infect. Immun. 43:850-855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sundstrom, P. M., and G. E. Kenny. 1985. Enzymatic release of germ tube-specific antigens from cell walls of Candida albicans. Infect. Immun. 49:609-614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sundstrom, P. M., E. J. Nichols, and G. E. Kenny. 1987. Antigenic differences between mannoproteins of germ tubes and blastospores of Candida albicans. Infect. Immun. 55:616-620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sundstrom, P. M., M. R. Tam, E. J. Nichols, and G. E. Kenny. 1988. Antigenic differences in the surface mannoproteins of Candida albicans as revealed by monoclonal antibodies. Infect. Immun. 56:601-606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Torosantucci, A., M. J. Gomez, C. Bromuro, I. Casalinuovo, and A. Cassone. 1991. Biochemical and antigenic characterization of mannoprotein constituents released from yeast and mycelial forms of Candida albicans. J. Med. Vet. Mycol. 29:361-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vargas, K., P. W. Wertz, D. Drake, B. Morrow, and D. R. Soll. 1994. Differences in adhesion of Candida albicans 3153A cells exhibiting switch phenotypes to buccal epithelium and stratum corneum. Infect. Immun. 62:1328-1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]