Abstract

Cdc42 is a small GTPase that is required for cell polarity establishment in eukaryotes as diverse as budding yeast and mammals. Par6 is also implicated in metazoan cell polarity establishment and asymmetric cell divisions. Cdc42·GTP interacts with proteins that contain a conserved sequence called a CRIB motif. Uniquely, Par6 possesses a semi-CRIB motif that is not sufficient for binding to Cdc42. An adjacent PDZ domain is also necessary and is required for biological effects of Par6. Here we report the crystal structure of a complex between Cdc42 and the Par6 GTPase-binding domain. The semi-CRIB motif forms a β-strand that inserts between the four strands of Cdc42 and the three strands of the PDZ domain to form a continuous eight-stranded sheet. Cdc42 induces a conformational change in Par6, detectable by fluorescence resonance energy transfer spectroscopy. Nuclear magnetic resonance studies indicate that the semi-CRIB motif of Par6 is at least partially structured by the PDZ domain. The structure highlights a novel role for a PDZ domain as a structural scaffold.

Keywords: crystallography/fluorescence/NMR/polarity/Rho GTPases

Introduction

Polarization of cells is a process of fundamental importance for virtually all organisms. In the metazoa, cell polarity establishment is required for asymmetric cell divisions that specify differential cell fates, morphogenesis and many physiological functions. One highly conserved gene product that has been implicated in cell polarity establishment is the partition-defective protein Par6 (Hung and Kemphues, 1999). Par6 participates in a multi-subunit complex with the Cdc42 GTPase, atypical protein kinases Cλ or ζ (aPKC) and another partition-defective protein, Par3 (Joberty et al., 2000; Lin et al., 2000; Qiu et al., 2000). All of these components are required for normal development (Watts et al., 1996; Joberty et al., 2000; Lin et al., 2000; Huynh et al., 2001; Petronczki and Knoblich, 2001; Suzuki et al., 2001; Gao et al., 2002). They have also been implicated in apical–basal cell polarity of mammalian epithelial cells and in polarization of migrating astrocytes (Nobes and Hall, 1999; Joberty et al., 2000; Etienne-Manneville and Hall, 2001; Gotta et al., 2001; Kay and Hunter, 2001; Ohno, 2001; Gao et al., 2002). Cdc42·GTP is essential for polarized cell divisions in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae as well as in metazoans, but the signaling pathway is quite different and no yeast homologs of Par6 exist.

Cdc42 in the GTP-bound state interacts with proteins that contain a short conserved sequence called a CRIB (Cdc42/Rac interactive binding) motif (Burbelo et al., 1995). Uniquely, Par6 possesses a semi-CRIB motif that is necessary, but not sufficient, for binding to Cdc42. An adjacent PDZ (PSD95/Discs Large/ZO-1) domain is also required and is essential for biological effects of Par6 (Ranganathan and Ross, 1997; Joberty et al., 2000). The N-terminus of Par6 forms a constitutive complex with aPKCs, and there is some evidence that the kinase activity of this protein is regulated by this interaction, such that an inhibitory effect of the CRIB/PDZ domain is relieved by Cdc42 binding (Etienne-Manneville and Hall, 2001; Yamanaka et al., 2001). We now report the crystal structure of a complex between Cdc42 and the GTPase-binding domain of Par6, which highlights a novel role for a PDZ domain as a structural scaffold, and demonstrates that emergent properties can arise from the juxtaposition of two distinct sequence motifs. Fluorescence spectroscopy detects changes in Par6 consistent with a conformational change induced by the binding of Cdc42.

Results and discussion

Biological activity of the isolated Par6 GBD

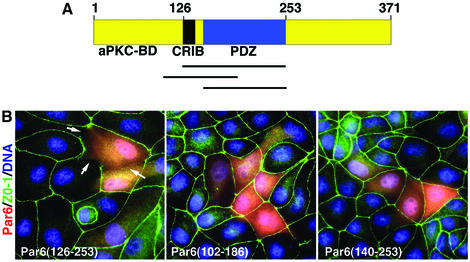

Uniquely, the minimum Cdc42 GTPase-binding domain (GBD) of Par6 comprises both a partial CRIB motif plus a PDZ domain (Joberty et al., 2000; Lin et al., 2000; Qiu et al., 2000). A schematic of the domain structure is provided in Figure 1A. We have shown previously that the overexpression of Par6 inhibits cell polarity establishment in MDCK epithelial cells, and that this effect is independent of aPKC binding (Joberty et al., 2000; Gao et al., 2002). We now demonstrate that the ectopic expression of the isolated GBD (residues 126–253) is sufficient to inhibit the assembly of tight junctions in epithelial cells (Figure 1B, left panel). Fragments lacking either the CRIB motif or a functional PDZ domain are, however, inactive (Figure 1B center, right panels).

Fig. 1. (A) Schematic of Par6B domain structure. (B) Inhibition of tight junction assembly by the GBD of Par6B. MDCK canine epithelial cells were transiently transfected with vectors that express myc-tagged versions of the Par6B GBD (semi-CRIB + PDZ; residues 126–253), the isolated PDZ domain (140–256) or the semi-CRIB motif alone (102–186). The cells were incubated in a calcium-free medium overnight to disrupt cell–cell contacts, then returned to normal DMEM/serum for 6 h to permit junction re-assembly. They were then washed and stained for the tight junction marker, Z0-1 (green), the myc tag (red) and DNA (blue).

Crystal structure of the Par6/Cdc42 GBD complex

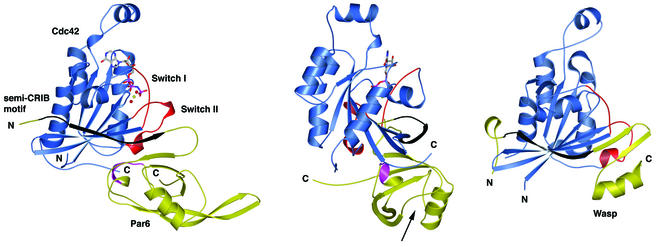

To understand the function of Par6 at a molecular level, we determined the crystal structure, to 2.1 Å resolution, of a complex between the biologically active GBD of Par6B and Cdc42(Q61L)·GMPPNP (Table I). The Par6 semi-CRIB motif binds Cdc42 in an extended conformation, forming an antiparallel β-sheet with the β2 strand of Cdc42, similar to the CRIB motifs of PAK, ACK and WASP (Figure 2; Abdul-Manan et al., 1999; Mott et al., 1999; Morreale et al., 2000). In contrast to these other effectors, however, a significant portion of the Par6 motif simultaneously forms an intra-molecular β-sheet with the βA strand of the PDZ domain, thereby creating an extended eight-stranded sheet within the complex (Figure 2).

Table I. Statistics of data collection and refinement.

| Space group | P1 |

| Cell dimensions | a = 41.7 Å, b = 53.8 Å, c = 79.5 Å, α = 81.6°, β = 76.6°, γ = 90.0° |

| No. of measurements | 80 223 |

| No. of independent reflections | 38 985 |

| Data range (Å) | 40.5–2.10 |

| Rmerge (%)a | |

| Overall | 10.4 |

| Last shell (2.14–2.10 Å) | 50.0 |

| Data completeness (%) | |

| Overall | 89.6 |

| Last shell | 87.1 |

| I/(σ)I | |

| Overall | 9.2 |

| Last shell | 2.0 |

| No. of reflections used in refinement | 34 917 (30.0–2.10 Å) |

| No. of non-H protein atoms | 4908 |

| No. of water molecules, GMPPNP, Mg2+ | 422, 2, 2 |

| Rwork (%) | 21.9 |

| Rfree (%)b | 27.3 |

| R.m.s.d. in bond lengths (Å) | 0.010 |

| R.m.s.d. in bond angles (°) | 1.7 |

| Mean B value (Å2) | |

| Cdc42 (all/main chain/side chain) | 28.7/27.5/29.9 |

| Par6 (all/main chain/side chain) | 26.5/25.3/27.8 |

| Water molecules, GMPPNP, Mg2+ | 34.5, 23.5, 19.9 |

| Cross-validated σA-coordinate error (Å) | 0.30 |

| Missing residues | Cdc42: none |

| Par6: 126–130 |

Fig. 2. Crystal structure of Par6B(126–253) bound to Cdc42(Q61L)·GMPPNP at 2.1 Å resolution. Ribbon diagram with Cdc42 colored blue and Par6 yellow (left and center images). A structure of the WASP–Cdc42 complex (Abdul-Manan et al., 1999) is also shown on the right, for comparison. The Switch I and II regions of Cdc42 are colored red, the semi-CRIB motif of Par6 and the CRIB motif of WASP are colored black, and the GMP-PNP/Mg2+(H2O)2 moiety is presented in ball-and-stick representation. A short region of the PDZ domain of Par6 (residues 204–208) that makes contact with Cdc42 is highlighted in magenta. The center image is of the complex rotated by 90° about the vertical axis. The black arrow indicates the location of the PDZ ligand-binding pocket.

The peptide ligand binding region of the PDZ domain maps to the βB strand and αB helix on the opposite face to that which connects through the semi-CRIB motif to Cdc42, suggesting that the GBD can bind each partner independently. Non-conserved residues in the semi-CRIB motif interact with the Switch I region of Cdc42, while residues in the loop and strand that are C-terminal to the CRIB motif, plus a five residue turn in the PDZ domain of Par6, interact with the Switch I and II regions.

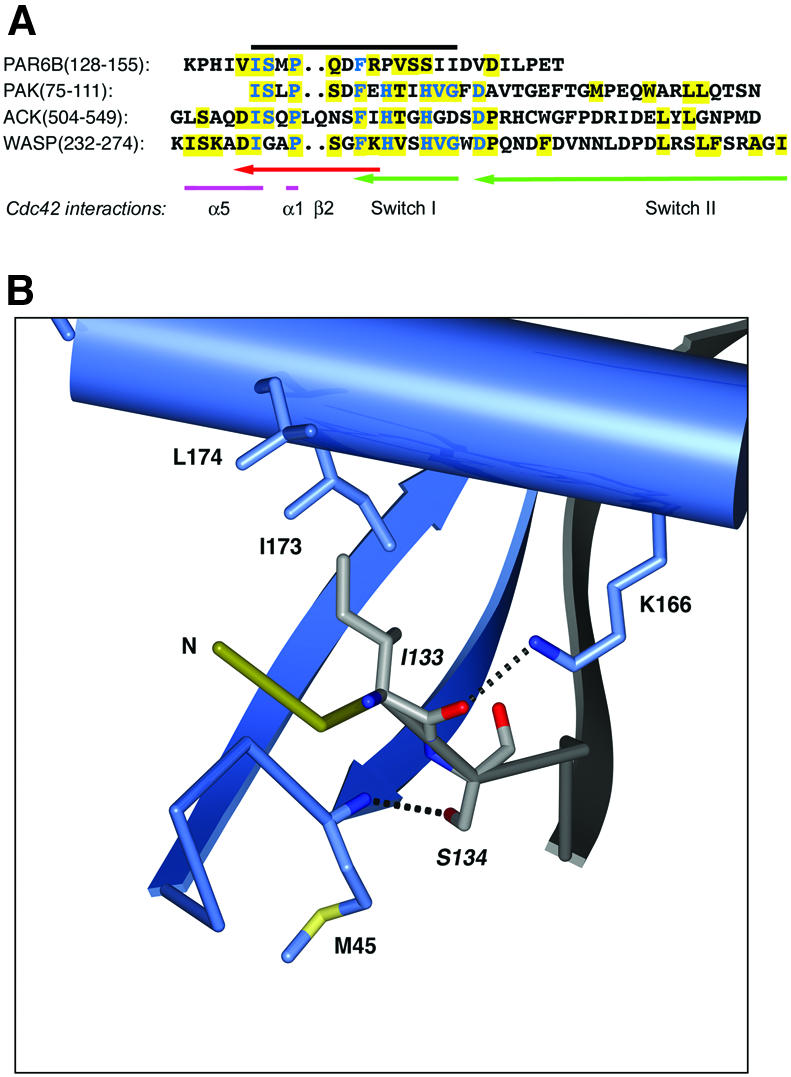

As in other Cdc42–effector complexes, the interaction surface for Par6 begins N-terminal to the first CRIB motif residue I133 (Figure 3A), but, in this case, is limited to a span of two residues. There is insufficient density in the experimental maps to model the first five residues (125–130) of the Par6 construct. There are no lattice contacts in this region of the crystal, thus the lack of order for this region of Par6 indicates that it does not bind tightly to Cdc42. A total of 14 hydrogen bonding interactions occur between the CRIB motif and Cdc42, of which nine are non-sequence-specific main chain–main chain bonds. The invariant residues of the Par6 semi-CRIB motif interact with Cdc42 in a similar fashion to other CRIB/Cdc42 structures. The isoleucine residue (Ile133 in Par6B, Figure 3B) packs into a groove between β2 and the C-terminal α5 helix of Cdc42, and the side chain hydroxyl of Ser134 forms a hydrogen bond with the main chain amide nitrogen of Met45 in Cdc42. The Pro and Phe residues (136 and 139 in Par6B) are positioned in a shallow hydrophobic groove on the Cdc42 surface containing Thr25 and Tyr40, but mutation of these residues in Par6B, unlike equivalent mutations in PAK, does not abolish binding to Cdc42·GTP (Joberty et al., 2000).

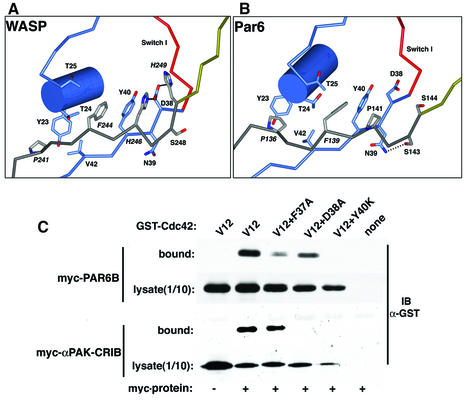

Fig. 3. (A) Alignment of Par6B semi-CRIB motif with CRIB sequences of PAK, ACK and WASP, and Cdc42 residues involved in binding Par6B. The black line indicates the extent of the consensus CRIB motif. Conserved residues are shown in blue; residues that interact with Cdc42 are boxed in yellow, with the corresponding region of Cdc42 marked beneath. Cdc42 residues are colored to indicate structural regions. (B) Sequence-specific interactions of the N-terminal portion of the semi-CRIB motif of Par6 with Cdc42. The coloring scheme is similar to Figure 2, with the semi-CRIB motif of Par6 colored in light gray for clarity. The labels for the residues of the consensus CRIB sequence motif are italicized. Dotted black lines represent salt bridges and hydrogen bonds. Non-sequence-specific hydrogen bonds (e.g., the main chain hydrogen bonds of the β-sheet) are not shown for clarity.

Binding of an Asp38 mutant of Cdc42 to Par6

A key difference between orthodox CRIB motifs and the semi-CRIB motif of Par6 is that the latter lacks two invariant His residues and a highly conserved Gly residue near the C-terminus of the element (Figure 3A). These His residues interact with Asp38 in the Switch I loop of Cdc42, and are essential for the binding of both PAK and WASP to the GTPase (Abdul-Manan et al., 1999; Mott et al., 1999; Morreale et al., 2000; Owen et al., 2000). The interaction with the WASP CRIB motif is shown in Figure 4A. By comparison (Figure 4B), the Par6 interaction is quite different. Pro141 replaces the first His residue, and has a limited van der Waals interaction with Cdc42 through Tyr40. The side chain hydroxyl of Ser143 forms a hydrogen bond with the side chain of Switch I residue Asn39. The second His residue in orthodox CRIB domains is replaced by Ser144, the side chain hydroxyl of which points away from Asp38.

Fig. 4. (A) Structure of the central region of a representative conformer of the CRIB motif of WASP with Cdc42 (PDB ID code 1cee). The coloring scheme is as shown in Figure 3. (B) For comparison, the sequence-specific interactions of the semi-CRIB motif of Par6 are shown in a similar orientation as in (A). (C) Asp38 is not required for binding of Par6 to Cdc42. Myc-tagged Par6B or, as a control, the CRIB domain of α-PAK, was immunoprecipitated from cells co-expressing GST fusions of Cdc42(Val12) that contain second mutations in the Switch I region. Bound GST–Cdc42 was detected by blotting with anti-GST antibody.

The unique lack of CRIB His residue interactions with Asp38 suggested that mutations of this residue, which is essential for high affinity binding of the GTPase to other effectors such as ACK, WASP and PAK (Owen et al., 2000), would not disrupt Par6 binding. We tested this prediction using glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusions of various Cdc42 mutants in a Gly12 (G12V) mutant background, co-transfected into Cos cells with myc-tagged Par6B. The CRIB domain of α-PAK was used as a control. The G12V mutant of Cdc42 is constitutively active, and as expected, was able to bind to both α-PAK and Par6 (Figure 4C). The introduction of a second Tyr40 (Y40K) mutation, which is known to disrupt binding to WASP and PAK (Owen et al., 2000), blocked the interaction with the α-PAK and Par6 (Figure 4C). The Asp38 mutation (D38A) also disrupted binding to α-PAK but, as predicted from our structure, binding to Par6 was retained, although at a reduced level. The affinity of the Y40K mutant for Par6 is >100-fold lower than that of the control, while the D38A mutant binds with an affinity that is ∼16-fold lower than the control (see below, Figure 7D).

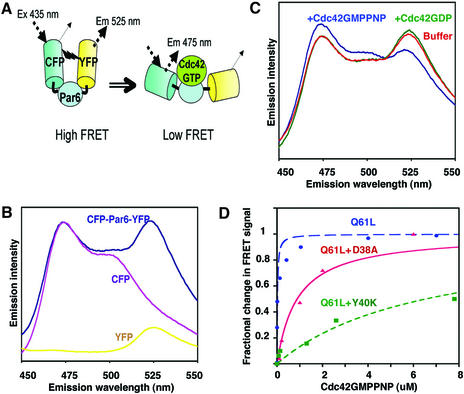

Fig. 7. Par6 B conformational biosensor. (A) Schematic of the biosensor structure, in the bound and unbound states, and emission spectra of the biosensor, CFP alone and YFP alone, excited at 433 nm. (B) Emission spectra of the CFP–Par6–YFP biosensor and of separated CFP and YFP. (C) Emission spectra of the biosensor and of CFP–YFP, each incubated with either Cdc42·GMPPNP or Cdc42·GDP (1 µM). (D) Titration curve of the Par6 biosensor incubated with varying concentrations of Q61L Cdc42 or the indicated mutants (in a Q61L background), all loaded with GMPPNP. The binding curve was fitted to the data assuming a single independent binding site, using Kaleidagraph software.

The Par6 PDZ domain

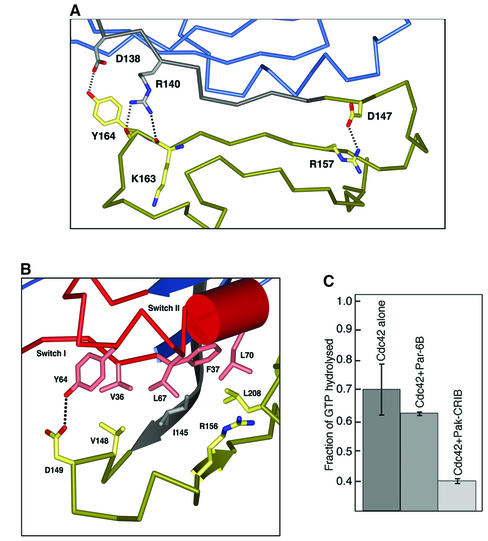

A radical difference between Par6 and other Cdc42 effectors is the requirement for an adjacent PDZ domain. An extended loop in Par6B, C-terminal to the semi-CRIB domain, folds the peptide chain away from Cdc42, and leads to the first β-strand of the PDZ domain. The CRIB motif strand is anchored to the first strand of the PDZ domain β-sheet via four main chain–main chain hydrogen bonds, and by sequence-specific interactions at each end of the sheet (Figure 5A). At the N-terminal end of the CRIB motif, the carboxylate side chain of Asp138 hydrogen bonds to the side chain hydroxyl of Tyr163, and the guanadinium group of Arg140 hydrogen bonds to the backbone carbonyls of residues 162 and 163. At the opposite end of the strand, the carboxylate of Asp147 forms a salt bridge with the guanadinium group of Arg157. It is possible that these interactions exist in the Cdc42 unbound state of Par6, and partially order the CRIB motif strand (see below).

Fig. 5. (A) The interaction of the semi-CRIB motif of Par6 with its PDZ domain. As in Figure 3, dotted black lines represent salt bridges and hydrogen bonds. Non-sequence-specific hydrogen bonds (e.g., the main chain hydrogen bonds of the β-sheet) are not shown for clarity. (B) The interactions of Par6 with the Switch I and II regions of Cdc42. (C) Effect of Par6 and PAK GBD domains on the intrinsic GTPase activity of Cdc42. Cdc42 loaded with [γ-32P]GTP was incubated for 10 min plus saturating concentrations (20× Kd) of the GST–GBD fusion proteins or GST alone. The Cdc42 was then bound to filters, washed to remove free 32P-phosphate and counted.

The extended loop between the CRIB motif and the PDZ domain limits the interaction of Par6 with the Switch I and II regions of Cdc42. Other residues of Par6 that make contact with Cdc42 occur in a short turn in the PDZ domain (204–208; highlighted in Figure 2). As a result, the buried surface area for the Par6/Cdc42 complex, at ∼1100 Å2, is the smallest of all characterized CRIB/Cdc42 structures, and approximately two-thirds the area of WASP/Cdc42 or the PAK/Cdc42 complex. All known effectors of Cdc42 that contain CRIB motifs bind through hydrophobic residues to Leu67 and Leu70 in Switch II, and restrict its conformational freedom. Specific Switch II interactions of the Par6/Cdc42 complex occur between Leu70 and Leu208 of Par6, and Leu67 and residues Ile145, Val148 and Arg156 of Par6 (Figure 5B). In addition, a hydrogen bond is formed between the side chain hydroxyl of Switch II residue Tyr64 and the side chain carboxylate of the CRIB motif residue Asp149. As a result of the limited interaction of Par6 with the Switch II region of Cdc42, the backbone of this loop adopts a conformation that is similar to the conformation observed in the aluminum fluoride transition state analog complex of Cdc42/Cdc42GAP (Nassar et al., 1998). In the PAK/Cdc42 structure, the loop C-terminal to the CRIB domain binds to the Switch II region, causing a large movement of the backbone away from the nucleotide-binding site. As a result, the side chain of the catalytically important residue 61 is close (<5 Å) to the γ-phosphate oxygen of the GMPPNP in the Par6 complex, but completely removed from the active site in the PAK complex (>10 Å). This may explain the observation that Par6 binding has little effect on the intrinsic rate of GTP hydrolysis, as compared with the PAK CRIB domain (Figure 5C).

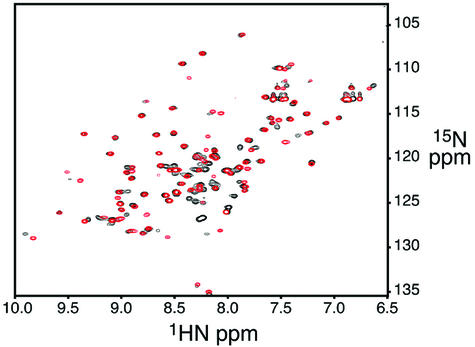

NMR spectra of Par6

A common property of the classical CRIB GBDs that have been studied to date is their lack of structure in the unbound state. The PAK and WASP GBDs contain a small region of stable α-helix C-terminal to the CRIB motif, but ACK is entirely disordered, and in each case, Cdc42·GTP induces the adoption of discrete structures (Abdul-Manan et al., 1999; Mott et al., 1999; Morreale et al., 2000). The consequent entropic penalty on binding may play a role in enhancing specificity of these interactions (Wright and Dyson, 1999; Dyson and Wright, 2002). To examine the degree of order in the CRIB motif of free Par6, we performed NMR analyses of two constructs: the isolated PDZ domain (residues 152–253) and the GBD (CRIB and PDZ, residues 126–253). 1H/15N HSQC spectra for both constructs show >90% of the expected backbone resonances (Figure 6).

Fig. 6. Overlaid 1H/15N HSQC spectra of the Par6 PDZ domain (residues 152–253, red) and CRIB–PDZ elements (residues 126–253, black).

While signals from the PDZ domain are identical in both cases, 23 backbone and two side chain signals show significant differences. Many of the largest differences occur in resonances with 1H chemical shift >9 p.p.m., suggesting they involve residues in the β-strands of the PDZ domain (Wuthrich, 1986). In systems where an independent, unfolded peptide is tethered to a folded domain, spectra of the isolated domain are typically a nearly exact subset of the full construct (Gosser et al., 1997), and the disordered elements in the longer protein give rise to intense resonances clustered in the center of the amide spectral window. Clearly, this is not the case for the Par6 proteins. The changes in PDZ domain chemical shifts on appending the CRIB motif, and absence of a significant number of intense resonances in the longer construct, indicate that the CRIB motif is at least partially structured in free Par6. Differences in β-strand amides of the PDZ domain suggest that the CRIB motif may form a structure similar to that observed in the Cdc42 complex, even in the absence of the GTPase, with residues C-terminal to approximately Phe139 bound to the side of the PDZ sheet. Preceding residues of the CRIB motif are likely disordered in the free protein. The reduction in ordering of C-terminal portions of the CRIB motif on binding the GTPase, and consequent reduction of a significant conformational entropic penalty on binding, may explain how Par6 can bind Cdc42 with high affinity even though its CRIB motif lacks conserved elements found in other systems (Burbelo et al., 1995).

Conformational change in Par6 detected by fluorescence resonance energy transfer

The stabilization of the CRIB motif by the adjacent PDZ domain is a new and unexpected function for a PDZ domain. It also raises the question of whether any conformational change in the Par6 GBD is induced by Cdc42 binding, particularly in the N-terminal region of the CRIB motif. To address this issue, we constructed a fluorescent biosensor from the Par6B GBD, based on fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) between two variants of the green fluorescent protein, CFP and YFP (Selvin, 1995; Heim and Tsien, 1996). The N- and C-termini of the Par6(126–253) are separated from one another by Cdc42 in the complex (see Figure 2), and based on this structure, we predicted that if CFP were to be attached to the N-terminus, and YFP to the C-terminus of the Par6 GBD, then Cdc42 binding might force the fluorophores apart and therefore lower the FRET signal between them (Figure 7A).

The CFP–Par6B(126–253)–YFP fusion displayed a robust FRET signal when the CFP was excited at 433 nm and YFP emission was monitored at 525 nm (Figure 7B). Separated CFP–Par6B and Par6B–YFP did not generate any FRET signal. Addition of Cdc42·GMPPNP, but not of Cdc42·GDP, induced a substantial fall in the FRET efficiency of the Par6B biosensor, suggesting that the binding of Cdc42 either separated the N- and C-termini of the Par6, or altered the averaged orientations of the two fluorophore dipoles relative to one another so as to reduce the energy transfer efficiency (Figure 7C). No change in FRET was observed when a CFP–YFP fusion lacking the Par6B insert was incubated with Cdc42(Q61L)·GMPPNP, further demonstrating that the effect is specific (data not shown). The Cdc42-specific change in FRET of the Par6 biosensor can be used to determine the affinity of the GBD for Cdc42. Titration of Cdc42·GMPPNP provided a Kd of ∼50 nM (Figure 7D), which is comparable to the affinities of the PAK and ACK GBD (23 nM), but is much lower than that of WASP (1.6 nM). The affinity of the G12V/D38A mutant of Cdc42 for Par6 (∼880 nM) was lower than that of the wild-type protein, but was much higher than that of the Q61L/Y40K mutant (>6 µM). Unexpectedly, titration of the Par6B biosensor revealed that Rac1 binds with a substantially lower affinity (∼1.5 µM) than Cdc42 does (data not shown), and, in the cell, Cdc42 is therefore likely to be the predominant ligand.

Conclusions

The interaction of Par6 with Cdc42 differs substantially from that of other Cdc42 effector proteins. Although the regions of Cdc42 that Par6 contacts are similar to those found in other Cdc42/CRIB motif complexes, they are less extensive and contain more polar interactions. (Abdul-Manan et al., 1999; Mott et al., 1999; Morreale et al., 2000). Moreover, a mutation in Asp38 of Cdc42, which disrupts binding to other effectors such as WASP, ACK and PAK, still permits Par6 binding. Unlike other CRIB domains, which are unstructured in the free protein, the semi-CRIB motif of Par6 is probably structured by the PDZ domain, and the absence of a significant conformational entropic penalty may explain how Par6 can bind Cdc42 with high affinity even though its CRIB motif lacks conserved elements found in other systems. Thus, the absence of conserved elements in the CRIB motif of Par6 and other Cdc42 effectors may be compensated by elimination of an entropic folding penalty on binding.

The marked preference of Par6 for Cdc42 over Rac1 was initially unexpected, as the sequences of Rac1 and Cdc42 in the Switch I and II regions that bind Par6 are identical. A comparison with Rac1 of the Par6-binding site of Cdc42 reveals the substitution of an asparagine for Thr43, an arginine for Leu174 and an aspartate for Gly47. Inspection of the Par6/Cdc42 complex structure indicates that the asparagine in position 43 probably does not interfere with the binding of Par6. In Rac1, however, the side chains of Arg174 and Asp47 form salt bridges, and could effectively block the insertion of the Par6 Ile133 into the hydrophobic groove between β2 and the C-terminal α5 helix of Cdc42, thereby effectively reducing the binding affinity of Par6 to Rac1 (Figure 3B).

The structural stabilization by the PDZ domain does not preclude movement of the N-terminal region of the CRIB motif, and the FRET data suggest that Cdc42 binding may induce a conformational change in Par6 that increases the separation (or alters the orientations) of the N- and C-termini of the GBD. Such a conformational change may account for the regulation of aPKC by Par6 and Cdc42. Residues 1–125 of Par6 bind with high affinity to the N-terminal regulatory domains of PKCζ and λ, and can stimulate kinase activity. This stimulation is suppressed by the GBD of Par6 except in the presence of Cdc42·GTP, which relieves the inhibitory effect (Yamanaka et al., 2001). A conformational change in Par6 that pushed the GBD away from bound aPKC would be consistent with this mechanism. Interestingly, the autoinhibitory elements in WASP and PAK are immediately C-terminal to the CRIB motif, and are extracted in response to Cdc42 binding (Kim et al., 2000; Lei et al., 2000; Buchwald et al., 2001). If Par6 employs a similar strategy, then the β1–β2 hairpin and/or the α1 helix of the PDZ domain might be predicted to act in the inhibition of aPKC. Further work will be necessary to test this model.

One unexpected insight from these studies is that emergent properties can result from the juxtaposition of two distinct sequence motifs. In Par6, the CRIB motif is unable to bind Cdc42 in the absence of the adjacent PDZ domain, although PDZ domains themselves do not bind GTPases. Conversely, the isolated PDZ domain has no detectable biological effect in the absence of the CRIB motif. The structural stability provided to the semi-CRIB motif of Par6 by the adjacent PDZ domain is a new type of function for this domain, and it will be of interest to determine whether it plays an equivalent role in other multi-domain proteins.

Materials and methods

Cell biology

MDCK cells were transfected using Effectene reagent (Quiagen) with 0.2 µg of pKmyc vectors that express various Par6B fragments. After 48 h, calcium was withdrawn as described previously, and cells were fixed 6 h after calcium re-addition (Gao et al., 2002). Cells were then stained with anti-ZO1 rabbit antibody and goat anti-rabbit conjugated to Oregon green, and with anti-myc antibody 9E10 and goat anti-mouse antibody conjugated to Texas Red. Images were collected on a Nikon Eclipse microscope with a 60× 1.2 na objective, a Hamamatsu CCD camera and Openlab software (Improvision).

Expression and purification of Par6/Cdc42 complex

Par6B(126–253) was produced as a GST fusion in Escherichia coli strain BL21(DE3). Expression was induced by 0.5 mM IPTG in Terrific Broth plus 2% ethanol at 18°C. After purification from bacterial lysate on glutathione–Sepharose beads, the GST was cleaved using His6-tagged Tev protease (72 h at 4°C). The Tev was removed with Ni2+-agarose beads. His6-Cdc42(Q61L) was expressed in the same way, but purified on Ni2+-agarose, in the presence of 5 mM MgCl2 and 100 µM GDP. The protein was loaded with GMPPNP for 5 h in 50 mM Tris pH 8.5, 200 mM ammonium sulfate, plus immobilized alkaline phosphatase on agarose beads to destroy free GDP. After addition of 2 mM MgCl2 to stabilize the bound nucleotide, the Cdc42 was mixed with excess Par6B(126–253) for 1 h, and the complex was purified over Ni2+-agarose. Finally, the His6 tag was removed from the Cdc42 by cleavage with Tev protease (48 h at 4°C). The complex was concentrated to 10 mg/ml and dialyzed into 20 mM Tris pH 8.5, 1 mm MgCl2, 100 µM GMPPNP and 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol. Tev protease was removed as above and the protein complex was snap frozen in 50 µl aliquots.

Protein crystallization and data collection

The Par6/Cdc42 complex was crystallized at 20°C using the hanging drop diffusion method. Clusters of small needles were first obtained in Hampton Screen 1 (Hampton Research), condition 9, after 48 h. Larger plate-like crystals (∼200 × 200 × 80 µm) were obtained via microseeding into drops of 1.5 µl protein and 1.5 µl of 24% Peg4000, 100 mM sodium citrate pH 6.4 and 0.2 M ammonium acetate. Crystals were soaked in a cryoprotectant solution of 20% ethylene glycol, 24% PEG 4000, 200 mM ammonium acetate and 100 mM sodium citrate pH 6.4 and flash frozen in liquid propane. The initial synchrotron diffraction data set used to phase the structure via molecular replacement was collected at 100°K to a dmin of 2.65 Å at the Structural Biology 19-BM beamline at the Advanced Photon Source (Argonne National Laboratory, Argonne, IL). A subsequent synchrotron diffraction data set used to refine the complex structure was collected at 100°K to a dmin of 2.10 Å at the Structural Biology 19-ID beamline. The diffraction data were indexed, integrated and scaled in the HKL2000 program package (Otwinoski and Minor, 1997). Intensities were converted to structure factor amplitudes and placed on an approximately absolute scale by the program TRUNCATE from the CCP4 package (French and Wilson, 1978; CCP4, 1994). The Par6/Cdc42 crystals were found to exhibit the symmetry of space group P1 (unit cell constants a = 41.7 Å, b = 53.8 Å, c = 79.5 Å, α = 81.6°, β = 76.6°, γ = 90.0°) with two complexes per asymmetric unit. Data collection and processing statistics for the high resolution data set are provided in Table I.

Crystallographic structure solution and refinement

The Par6/Cdc42 complex structure was solved via molecular replacement using the program AMORE (Navaza, 1994). Initial model coordinates for Cdc42 were obtained by modifying the coordinates from the Cdc42GAP(R305A mutant)/Cdc42-GDP-ALF4– complex (Protein Data Bank code 2ngr; Nassar et al., 1998) by truncating the C-terminus of the protein at residue 180 and changing the side chain of Gln61 to a leucine. The rotation and translation function search was conducted between a dmin of 10.0 and 4.0 Å with the initial synchrotron data set using a monomer model of Cdc42, and a solution was obtained for two monomers in the asymmetric unit with a combined correlation coefficient of 0.51. Rigid-body refinement of the coordinates from this solution versus data between a dmin of 20.0 and 3.0 Å was conducted in the program package CNS 1.1 (Brünger et al., 1998) with a random 5% subset of all data set aside for an Rfree calculation. Examination of the resulting electron density map in the program O (Jones et al., 1991) revealed extra density in the CRIB motif binding region of Cdc42. This density for an extended β-strand of ∼10 residues was connected, but the side chain density was very weak. A complete model for Par6 was built via repeated cycles of NCS averaging and solvent flattening in the program dm (Cowtan and Main, 1998), followed by skeletonization of the resulting map with the program Mapman (Read and Kleywegt, 2001), poly-alanine model building in O, simulated annealing refinement in CNS 1.1, skeletonization of the resulting CNS (2Fobs – Fcalc) map and new mask generation in dm for the next cycle of averaging and solvent flattening.

All refinement calculations were performed in the program CNS 1.1. Cycles of standard positional and individual isotropic atomic displacement parameter refinement coupled with cycles of model rebuilding and addition of solvent molecules were carried out against all data from 30.0 to 2.10 Å. The current model has working and free R values of 21.9% and 27.3%, respectively, against the experimental data. There are no outliers in the Ramachandran plot. The final model for each complex in the asymmetric unit contains five residues from the N-terminal tag (–5 to –1) and residues 2–190 of Cdc42, residues 131–253 of Par6, one GMPPNP and one Mg2+ ion with two bound waters. An additional 418 water molecules are also present in the final model. Complete refinement statistics for the structure are listed in Table I. Coordinates have been deposited with the Protein Data Bank under the accession code 1NF3.

NMR spectroscopy

The isolated PDZ domain of Par6B (residues 152–253) and Par6B(126–253) were each labeled with 15N by expression as GST–His6 fusion proteins in a minimal medium containing 15NH4Cl supplemented with Bioexpress medium (1/100). Proteins were purified and cleaved as described above, then dialyzed into 50 mM Na phosphate pH 6.8, 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 2 mM MgCl2 and 0.2% NaN3. 1H/15N HSQC spectra of Par6 proteins were recorded on a Varian Inova 600 spectrometer at 25°C using sensitivity enhanced pulse sequences with gradient coherence selection (Kay et al., 1992). Samples were 100–200 µM protein in 50 mM phosphate pH 6.7, 50 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol and 0.2% NaN3 buffer.

Fluorescence spectroscopy

Par6B(126–253) was expressed as a His6-tagged CFP–Par6–YFP fusion protein in E.coli strain BL21(DE3). Protein from bacterial lysates was purified over Ni2+-agarose. Cdc42 proteins were expressed as GST fusions and purified over a glutathione–Sepharose column. The GST tag was cleaved by thrombin, and the free GST and the thrombin were removed using glutathione– and p-aminobenzamidine–Sepharose beads, respectively. Fluorescence emission spectra were obtained in buffer containing 25 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 100 mM MgSO4, 10 mM β-mercapto ethanol and 1% BSA, on a Spex Fluorolog-tau3 spectrofluorometer, using a 5 mm rectangular cuvette (25°C). Excitation was at 433 nm (slit width 3 nm). The loss of fluorescence at 525 nm was monitored on titration with Cdc42(Q61L)·GMPPNP over a range of 10–7000 nM.

Biochemical assays

Cdc42 effector domain mutants in pEBG were kindly provided by Margaret Chou (University of Pennsylvania), and were co-expressed as GST fusions in Cos cells after co-transfection with pKmyc-Par6B, or pKmyc-αPAK CRIB domain. After immuno-precipitation from cell lysates with anti-Myc antibodies, bound proteins were separated by SDS–PAGE and detected by blotting with an anti-GST antibody. GTPase protection assays were performed using wild-type Cdc42, GST– Par6B(1–271) and GST–γPAK CRIB. Cdc42 was loaded with [γ-32P]GTP and incubated with 9 µM Par6, 3 µM PAK or 3 µM GST at 30°C for 0–10 min. Samples were then bound to nitrocellulose filters, washed and counted for retained 32P.

PDB accession codes

The coordinates and structure factors for the Par6/Cdc42 structure have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under accession code 1NF3. The RCSB ID code is RCSB017816.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Sandra Hill for excellent technical assistance in analyzing suitable constructs for crystallization, Mischa Machius for data collection, Claudia Low for help with the PDB submission, and Andrzej Joachimiak and the staff of the Structural Biology Center beamline (19-BM and 19-ID) at the Advanced Photon Source for assistance in X-ray data collection. Use of the Argonne National Laboratory Structural Biology Center beamlines at the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, under Contract No. W-31-109-ENG-38. This work was supported by grants CA40042 (to I.G.M.) and GM56322 (to M.K.R.) from the National Institutes of Health, DHHS.

References

- Abdul-Manan N., Aghazadeh,B., Liu,G.A., Majumdar,A., Ouerfelli,O., Siminovitch,K.A. and Rosen,M.K. (1999) Structure of Cdc42 in complex with the GTPase-binding domain of the ‘Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome’ protein. Nature, 399, 379–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brünger A.T. et al. (1998) Crystallography and NMR system: a new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D, 54, 905–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchwald G., Hostinova,E., Rudolph,M.G., Kraemer,A., Sickmann,A., Meyer,H.E., Scheffzek,K. and Wittinghofer,A. (2001) Conformational switch and role of phosphorylation in PAK activation. Mol. Cell. Biol., 21, 5179–5189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burbelo P.D., Drechsel,D. and Hall,A. (1995) A conserved binding motif defines numerous candidate target proteins for both Cdc42 and Rac GTPases. J. Biol. Chem., 270, 29071–29074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CCP4 (1994) The CCP4 suite of programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D, 50, 760–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowtan K. and Main,P. (1998) Miscellaneous algorithms for density modification. Acta Crystallogr. D, 54, 487–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyson H.J. and Wright,P.E. (2002) Coupling of folding and binding for unstructured proteins. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol., 12, 54–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etienne-Manneville S. and Hall,A. (2001) Integrin-mediated activation of Cdc42 controls cell polarity in migrating astrocytes through PKCζ. Cell, 106, 489–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French S. and Wilson,K. (1978) On the treatment of negative intensity observations. Acta Crystallogr. A, 34, 517–525. [Google Scholar]

- Gao L., Joberty,G. and Macara,I.G. (2002) Assembly of epithelial tight junctions is negatively regulated by Par6. Curr. Biol., 12, 221–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosser Y.Q., Nomanbhoy,T.K., Aghazadeh,B., Manor,D., Combs,C., Cerione,R.A. and Rosen,M.K. (1997) C-terminal binding domain of Rho GDP-dissociation inhibitor directs N-terminal inhibitory peptide to GTPases. Nature, 387, 814–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotta M., Abraham,M.C. and Ahringer,J. (2001) CDC-42 controls early cell polarity and spindle orientation in C. elegans. Curr. Biol., 11, 482–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim R. and Tsien,R.Y. (1996) Engineering green fluorescent protein for improved brightness, longer wavelengths and fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Curr. Biol., 6, 178–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung T.J. and Kemphues,K.J. (1999) PAR-6 is a conserved PDZ domain-containing protein that colocalizes with PAR-3 in Caenorhabditis elegans embryos. Development, 126, 127–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh J.R., Petronczki,M., Knoblich,J.A. and St Johnston,D. (2001) Bazooka and PAR-6 are required with PAR-1 for the maintenance of oocyte fate in Drosophila. Curr. Biol., 11, 901–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joberty G., Petersen,C., Gao,L. and Macara,I.G. (2000) The cell-polarity protein Par6 links Par3 and atypical protein kinase C to Cdc42. Nat. Cell Biol., 2, 531–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones T.A., Zou,J.Y., Cowan,S.W. and Kjeldgaard,M. (1991) Improved methods for building protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models. Acta Crystallogr. A, 47, 110–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay A.J. and Hunter,C.P. (2001) CDC-42 regulates PAR protein localization and function to control cellular and embryonic polarity in C. elegans. Curr. Biol., 11, 474–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay L.E., Keifer,P. and Saarinen,T. (1992) Pure absorption gradient enhanced heteronuclear single quantum correlation spectroscopy with improved sensitivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 114, 10663–10665. [Google Scholar]

- Kim A.S., Kakalis,L.T., Abdul-Manan,N., Liu,G.A. and Rosen,M.K. (2000) Autoinhibition and activation mechanisms of the Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein. Nature, 404, 151–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei M., Lu,W., Meng,W., Parrini,M.C., Eck,M.J., Mayer,B.J. and Harrison,S.C. (2000) Structure of PAK1 in an autoinhibited conformation reveals a multistage activation switch. Cell, 102, 387–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin D., Edwards,A.S., Fawcett,J.P., Mbamalu,G., Scott,J.D. and Pawson,T. (2000) A mammalian PAR-3–PAR-6 complex implicated in Cdc42/Rac1 and aPKC signalling and cell polarity. Nat. Cell Biol., 2, 540–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morreale A., Venkatesan,M., Mott,H.R., Owen,D., Nietlispach,D., Lowe,P.N. and Laue,E.D. (2000) Structure of Cdc42 bound to the GTPase binding domain of PAK. Nat. Struct. Biol., 7, 384–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mott H.R., Owen,D., Nietlispach,D., Lowe,P.N., Manser,E., Lim,L. and Laue,E.D. (1999) Structure of the small G protein Cdc42 bound to the GTPase-binding domain of ACK. Nature, 399, 384–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nassar N., Hoffman,G.R., Manor,D., Clardy,J.C. and Cerione,R.A. (1998) Structures of Cdc42 bound to the active and catalytically compromised forms of Cdc42GAP. Nat. Struct. Biol., 5, 1047–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navaza J. (1994) AMORE: an automated package for molecular replacement. Acta Crystallogr. A, 50, 157–163. [Google Scholar]

- Nobes C.D. and Hall,A. (1999) Rho GTPases control polarity, protrusion and adhesion during cell movement. J. Cell Biol., 144, 1235–1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno S. (2001) Intercellular junctions and cellular polarity: the PAR–aPKC complex, a conserved core cassette playing fundamental roles in cell polarity. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol., 13, 641–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinoski Z. and Minor,W. (1997) Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol., 276, 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen D., Mott,H.R., Laue,E.D. and Lowe,P.N. (2000) Residues in Cdc42 that specify binding to individual CRIB effector proteins. Biochemistry, 39, 1243–1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petronczki M. and Knoblich,J.A. (2001) DmPAR-6 directs epithelial polarity and asymmetric cell division of neuroblasts in Drosophila. Nat. Cell Biol., 3, 43–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu R.G., Abo,A. and Steven Martin,G. (2000) A human homolog of the C. elegans polarity determinant Par-6 links Rac and Cdc42 to PKCζ signaling and cell transformation. Curr. Biol., 10, 697–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranganathan R. and Ross,E.M. (1997) PDZ domain proteins—scaffolds for signaling complexes. Curr. Biol., 7, R770–R773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read R.J. and Kleywegt,G.J. (2001) Density modification: theory and practice. In Turk,D. and Johnson,L. (eds), Methods Macromolecular Crystallography. IOS Press, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, pp. 123–135.

- Selvin P.R. (1995) Fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Methods Enzymol., 246, 300–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki A. et al. (2001) Atypical protein kinase C is involved in the evolutionarily conserved par protein complex and plays a critical role in establishing epithelia-specific junctional structures. J. Cell Biol., 152, 1183–1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts J.L., Etemad-Moghadam,B., Guo,S., Boyd,L., Draper,B.W., Mello,C.C., Priess,J.R. and Kemphues,K.J. (1996) Par-6, a gene involved in the establishment of asymmetry in early C. elegans embryos, mediates the asymmetric localization of PAR-3. Development, 122, 3133–3140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright P.E. and Dyson,H.J. (1999) Intrinsically unstructured proteins: re-assessing the protein structure–function paradigm. J. Mol. Biol., 293, 321–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuthrich K. (1986) NMR of Proteins and Nucleic Acids. John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY, pp. 162–175.

- Yamanaka T. et al. (2001) PAR-6 regulates aPKC activity in a novel way and mediates cell–cell contact-induced formation of the epithelial junctional complex. Genes Cells, 6, 721–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]