Abstract

All living organisms have to protect the integrity of their genomes from a wide range of genotoxic stresses to which they are inevitably exposed. However, understanding of DNA repair in plants lags far behind such knowledge in bacteria, yeast, and mammals, partially as a result of the absence of efficient in vitro systems. Here, we report the experimental setup for an Arabidopsis in vitro repair synthesis assay. The repair of plasmid DNA treated with three different DNA-damaging agents, UV light, cisplatin, and methylene blue, after incubation with whole-cell extract was monitored. To validate the reliability of our assay, we analyzed the repair proficiency of plants depleted in AtRAD1 activity. The reduced repair of UV light– and cisplatin-damaged DNA confirmed the deficiency of these plants in nucleotide excision repair. Decreased repair of methylene blue–induced oxidative lesions, which are believed to be processed by the base excision repair machinery in mammalian cells, may indicate a possible involvement of AtRAD1 in the repair of oxidative damage. Differences in sensitivity to DNA polymerase inhibitors (aphidicolin and dideoxy TTP) between plant and human cell extracts were observed with this assay.

INTRODUCTION

The genomes of all living organisms are constantly subjected to a wide range of genotoxic stresses induced by environmental factors (e.g., UV-B irradiation, bacterial and fungal toxins) as well as by the intermediate products of normal cellular metabolism (e.g., alkylating and oxidizing agents). These can lead to the formation of different types of DNA damage, the persistence of which can block DNA replication and transcription or cause cell cycle arrest and apoptosis (Britt, 1999; Lindahl and Wood, 1999). Incorrect repair can result in heritable point mutations or gross rearrangements such as deletions and insertions. To keep the integrity of their genomes, all organisms have evolved protective mechanisms of repair of a broad variety of DNA lesions. According to the mode of action, the substrate specificity, and the size of the excised DNA fragment, these pathways generally have been classified as direct repair, base excision repair (BER), nucleotide excision repair (NER), and mismatch repair (reviewed by Friedberg, 1996; Sancar, 1996; Wood, 1996; Lindahl and Wood, 1999). These mechanisms were first described in bacteria and later characterized extensively in yeast and mammals (Sancar, 1996; Laat et al., 1999; Le Page et al., 2000; Memisoglu and Samson, 2000). Unfortunately, with the exception of light-dependent reversion of UV light–induced pyrimidine dimers by photolyases, very little is known about DNA repair pathways in plants (reviewed by Vonarx et al., 1998; Britt, 1999).

To study different types of DNA repair mechanisms in vitro, the formation of pathway-specific DNA lesions is required. For the study of NER, we chose the following DNA-damaging agents: UV-C and cis-diamminedichloroplatinum II (cisplatin). Additionally, methylene blue–treated DNA was used to distinguish the relative contributions of NER and BER.

The UV-C type of DNA damage can be classified broadly as bulky lesions, which include cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers (CPD) and pyrimidine-pyrimidinone photoproducts (6-4-PP); minor lesions, which do not distort the DNA helix, including thymine glycols (Tg), pyrimidine hydrates, and 8-hydroxoguanosine (8-oxoG); and single- or double-strand breaks and DNA–protein and DNA–DNA cross-links (McLennan, 1987). In yeast and human cells, it is known that CPD and 6-4-PP are repaired by NER, whereas Tg, pyrimidine hydrates, and 8-oxoG are the substrate for BER (reviewed by Demple and Harrison, 1994; Wood, 1996). The widely prescribed anticancer chemotherapeutic drug cisplatin forms adducts with DNA consisting mainly of intrastrand cross-links with guanine bases in the form of 1,2-d(GpG)cisplatin (Chu, 1994; Zlatanova et al., 1998). These adducts are repaired by the human NER pathway and often are used as model substrates to monitor NER activity (reviewed by Zamble and Lippard, 1995). As a BER target, we chose a methylene blue treatment that in the presence of visible light induces predominantly 8-oxoG on double-stranded DNA (Schneider et al., 1990).

It is accepted generally that in vitro assays are required to show the function of various DNA repair genes. The incorporation of radioactively labeled nucleotides during the DNA repair process was one of the first in vitro assays described for the human lymphoid cell extract (Wood et al., 1988). This was optimized further for the detection of NER in mammalian cells (Aboussekhra et al., 1995; Wood et al., 1995; Jaiswal et al., 1998) and in yeast (He et al., 1996; Wang et al., 1995, 1996; You et al., 1998). To the best of our knowledge, this approach has not been used to monitor DNA repair in plants. The only related assay was reported by Gamper et al. (2000) and Rice et al. (2000) for the estimation of mismatch repair proficiency of plant cell-free extracts. They used chimeric RNA/DNA oligonucleotides as a repair template to monitor the conversion of point and frameshift mutations on plasmid DNA.

Recently, we isolated and characterized the Arabidopsis gene atrad1, which encodes the plant homolog of Saccharomyces cerevisiae RAD1–specific endonuclease involved in NER (Gallego et al., 2000). Arabidopsis lines depleted for AtRAD1 were hypersensitive to UV-B, UV-C, and γ irradiation (Fidantsef et al., 2000; Gallego et al., 2000; Liu et al., 2000), and although we showed the involvement of AtRAD1 in dark excision repair of UV light–damaged DNA, the exact role of AtRAD1 in excision repair is not clear, and its participation in other repair pathways cannot be excluded.

Thus, the goal of the present work was to establish a reliable assay for the detection of NER in plants and to test the proficiency of transgenic AtRAD1 antisense plants in resolving different repair substrates compared with that of wild-type plants. To monitor the repair of damaged DNA, we chose and optimized an in vitro repair synthesis assay. With this approach, we have shown that an Arabidopsis whole- cell extract, as well as a control human cell extract, is able to support in vitro repair synthesis on plasmid DNA damaged by UV light, cisplatin, or methylene blue. Using this assay, we have found that plants depleted in AtRAD1 activity by antisense-mediated downregulation of the transcript are altered in the repair of all types of DNA adducts tested. The reduced repair of methylene blue–induced 8-oxoG lesions (Schneider et al., 1990), which are believed to be repaired through BER in mammalian cells (Demple and Harrison, 1994), may indicate a direct or indirect involvement of NER enzymes in the repair of oxidative DNA damage in plants. We also observed differences in sensitivity to the DNA polymerase inhibitors aphidicolin and dideoxy (dd) TTP between human and plant extracts, a fact that may suggest the recruitment of different DNA polymerases for DNA repair in plants compared with human cells.

RESULTS

Arabidopsis Whole-Cell Extract Supports in Vitro Repair Synthesis of UV Light–Damaged DNA

Initially, we needed to establish an appropriate and reliable assay to monitor DNA repair in plants. In vitro repair synthesis, which was first established for extracts prepared from human lymphoid cells (Wood et al., 1988) and then used widely by different groups to monitor NER in yeast and human cells, was chosen. According to the classic model for NER, the segment of DNA containing the damage is excised by NER-specific endonucleases (XPF-ERCC1 and XPG or RAD1-RAD10 and RAD2 in human and yeast, respectively) as a single-stranded oligonucleotide 24 to 32 bases long (Lindahl and Wood, 1999; Prakash and Prakash, 2000). The resulting gap then is filled in with a DNA polymerase and sealed with a DNA ligase. The incorporation of labeled deoxynucleotide triphosphate into damaged plasmid DNA after incubation with cell extract as a source of repair enzymes directly reflects the repair efficiency.

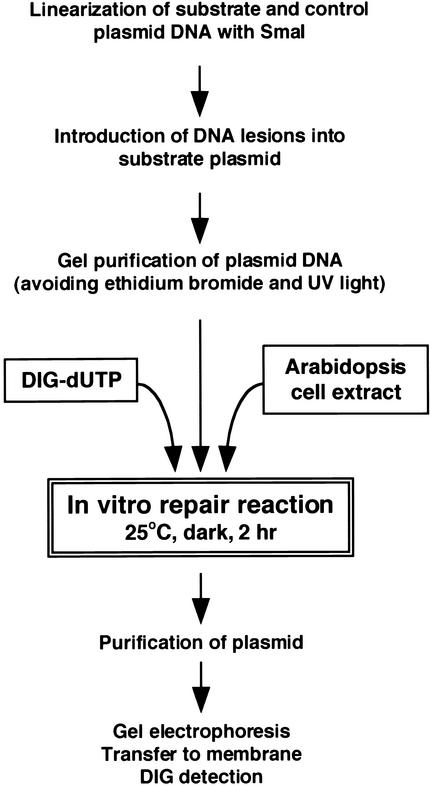

To ensure a clear and strong correlation between DNA damage and the efficiency of in vitro synthesis in plant extracts, we introduced the following modifications into the protocol described by Wood et al. (1995) (Figure 1). First, instead of radioactive nucleotides, we used digoxigenin-labeled deoxyuridine triphosphate (DIG-dUTP), which has several advantages over radioactive methods (safe handling, no problem with decay, and short exposure time). Second, the incubation of UV light–damaged DNA substrate with plant extracts was performed in complete darkness to avoid any photoreactivation by plant photolyases and at 25°C, the physiological temperature optimum for Arabidopsis proteins. Finally, plasmid DNA used as a repair substrate and an internal control was linearized before incubation, because the presence of unrepaired adducts can affect subsequent digestion with restriction enzymes. Indeed, we observed a linear decrease of the efficiency of SmaI digestion (recognition site CCCGGG) of a plasmid DNA damaged by cisplatin at increasing concentrations (data not shown). Similarly, cisplatin-damaged plasmid DNA failed to be digested by StuI (recognition site TCCGGA) (Szymkowski et al., 1992).

Figure 1.

Scheme of the in Vitro Repair Assay for Arabidopsis Whole-Cell Extract.

For a detailed description of the each step, see Methods.

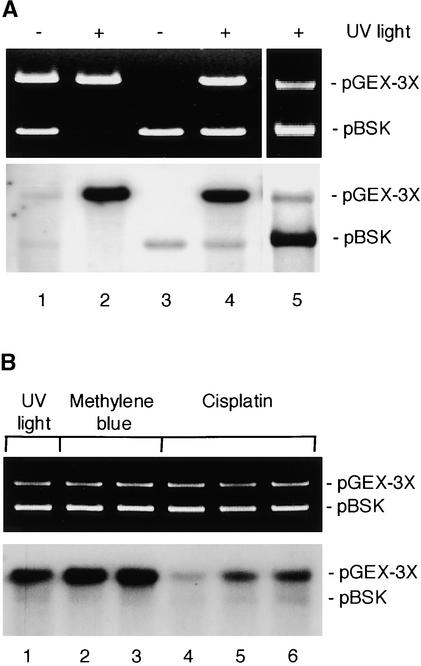

Strong labeling of UV light–damaged pGEX-3X DNA was detected upon incubation with plant extract (Figure 2A, lanes 2 and 4). Nondamaged plasmid DNA used as an internal control did not incorporate any significant amount of label (Figure 2A, pBluescript II SK+ [pBSK] in lanes 1, 3, and 4 and pGEX-3X in lanes 1 and 5). The correlation between DNA damage and the intensity of the signal also was observed when UV light–irradiated pBSK was used as a substrate for repair and nondamaged pGEX-3X was used as a control (Figure 2A, lane 5). Additionally, we found a linear dependence of DIG incorporation on UV light dose applied (50, 250, and 500 J/m2) as well as on time of incubation with cell extract (data not shown). Notably, when the repair reaction was performed in the presence of visible light, almost no DIG labeling of UV-irradiated plasmid was detected, most likely because of the efficient CPD reversal by photolyases (data not shown). These results provided clear evidence that the modified method is applicable for monitoring the repair of UV light–damaged plasmid DNA and that Arabidopsis whole-cell extract is proficient in this repair.

Figure 2.

In Vitro Repair Synthesis of Damaged Plasmid DNA in Arabidopsis Cell Extract.

SmaI-digested pGEX-3X and pBSK plasmid DNA were damaged as indicated and incubated with a plant extract in the presence of DIG-labeled dUTP. After purification, plasmid DNA was separated by agarose gel electrophoresis, transferred to a membrane, and detected with anti-DIG–alkaline phosphatase antibodies. Chemiluminescence was registered on x-ray film. For both (A) and (B), gel at top and film at bottom.

(A) Lane 1, nondamaged pGEX-3X plus pBSK; lane 2, UV light–irradiated pGEX-3X; lane 3, nondamaged pBSK; lane 4, UV light–irradiated pGEX-3X plus nondamaged pBSK; lane 5, nondamaged pGEX-3X plus UV light–irradiated pBSK.

(B) Nondamaged pBSK was used as an internal control, and pGEX-3X was treated as follows: lane 1, UV light irradiation (450 J/m2); lane 2, 10 μg/mL methylene blue and 30 min of illumination by visible light; lane 3, 10 μg/mL methylene blue and 60 min of illumination by visible light; lane 4, 1 μM cisplatin; lane 5, 5 μM cisplatin; lane 6, 10 μM cisplatin.

Cisplatin- and Methylene Blue–Damaged DNA Is Repaired Efficiently in Vitro

Apart from pyrimidine dimers, which are repaired by NER, UV light also induces a small number of lesions, which serve as substrates for glycosidase and are repaired through the BER pathway (Sancar, 1996). To distinguish which mechanism is involved in the repair reaction detected on UV light–irradiated DNA, we designed separate substrates for NER and BER. Cisplatin-treated DNA was chosen as a classic substrate for NER activity (reviewed by Zamble and Lippard, 1995), whereas treatment with methylene blue plus visible light was used to induce oxidative damage (mainly 8-oxoG), which serves as a substrate for BER (reviewed by Demple and Harrison, 1994). When DNA samples exposed to different damaging agents were incubated with the plant extract, clear damage-dependent incorporation of label was observed in all three cases (Figure 2B). The signal intensity was strongest in the case of methylene blue–damaged DNA, weaker for the UV light–irradiated plasmid, and weaker still for platinated DNA.

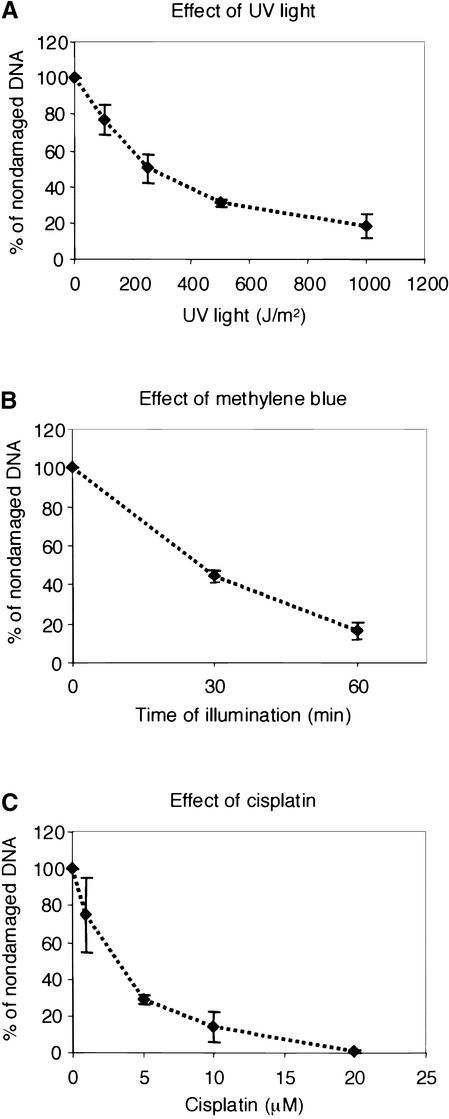

To compare and to standardize the extent of DNA damage induced by defined doses of the mutagenic agents used, their deleterious effect on transcription was evaluated in tobacco protoplasts. The plasmid pPP24 containing the firefly luciferase gene (f-luc) was treated with UV light, cisplatin, or methylene blue at different doses. Nondamaged pRR22 plasmid expressing Renilla luciferase (r-luc) was cotransfected as an internal standard for the transformation efficiency. The enzymatic activity of f-LUC in the protoplast extract was determined, standardized against r-LUC activity, and used as a measure of DNA integrity (Figure 3). The UV light dose of 450 J/m2 resulted in ∼70% inhibition of f-luc expression (Figure 3A). The same level of transcriptional inhibition was observed for DNA treated with 5 μM cisplatin (Figure 3C) and with 10 μg/mL methylene blue exposed for 45 min to visible light (Figure 3B). Therefore, in subsequent experiments, these conditions were used for the induction of DNA damage.

Figure 3.

Inhibition of luciferase Expression by Different DNA-Damaging Agents.

pPP22 plasmid DNA containing a firefly luciferase gene was damaged as indicated by UV light (A), 10 μg/mL methylene blue and visible light (B), or cisplatin (C) and used to transform tobacco protoplasts. pRR22 plasmid DNA expressing Renilla luciferase was cotransformed as an internal control. After recovery, the activity of firefly luciferase was measured and standardized against Renilla luciferase activity. The relative firefly luciferase activity of damaged plasmid DNA was compared with that of nondamaged DNA (100% activity). Error bars represent standard deviations of the means of two independent experiments.

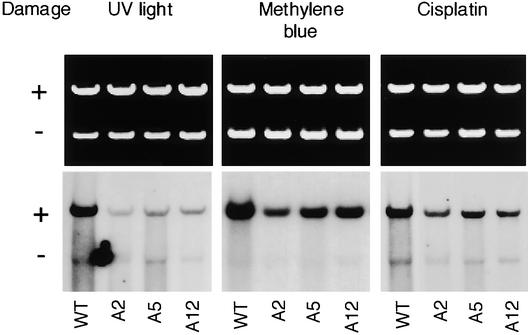

DNA damage induced by the treatments that resulted in the same 70% inhibition of luciferase expression was repaired with different efficiencies (Figure 4, WT extract lanes). The highest rate of DIG-dUTP incorporation was observed on methylene blue–treated DNA. The main type of methylene blue–induced lesions, 8-oxoG, is believed to be repaired via short patch BER in which only the damaged base is removed, leading to weak, if any, incorporation of labeled dUTP. Thus, the high efficiency of DIG-dUTP incorporation observed in the case of methylene blue–damaged DNA cannot be explained by the classic BER model alone and suggests the involvement of alternative pathways in the repair of 8-oxoG. NER could be one of the candidates for this role.

Figure 4.

In Vitro Repair Synthesis in Cell Extracts from Wild-Type and AtRAD1 Antisense Plants.

Standard repair reactions were performed on pGEX-3X DNA damaged by 450 J/m2 UV light, by 10 μg/mL methylene blue and 45 min of illumination with visible light, and by 5 μM cisplatin. Nondamaged pBSK was used as an internal control. A2, A5, and A12, antisense plants; WT, wild type.

Transgenic Plants Depleted in AtRAD1 Activity Are Ineffective in DNA Repair in Vitro and in Vivo

To test for the possible involvement of NER in the repair of oxidative damage, UV light–, methylene blue–, and cisplatin-damaged DNA samples were incubated with plant extracts from lines depleted of AtRAD1 by an antisense approach. These Arabidopsis lines have been shown to be more sensitive to UV light and the DNA cross-linking agent mitomycin C and to be impaired in “dark” CPD repair, which indicates their deficiency in the NER pathway (Gallego et al., 2000). Extracts from three transgenic lines were prepared and tested for in vitro repair efficiency. As shown in Figure 4, all transgenic plants were altered to different extents in the repair of UV light– and cisplatin-damaged DNA, which confirms their impairment in the NER pathway. At the same time, they also were less efficient than were wild-type plants in the repair of methylene blue–treated DNA, supporting the idea of an overlap of NER and BER in the removal of oxidative damage in plants, as was reported previously for yeast (Swanson et al., 1999).

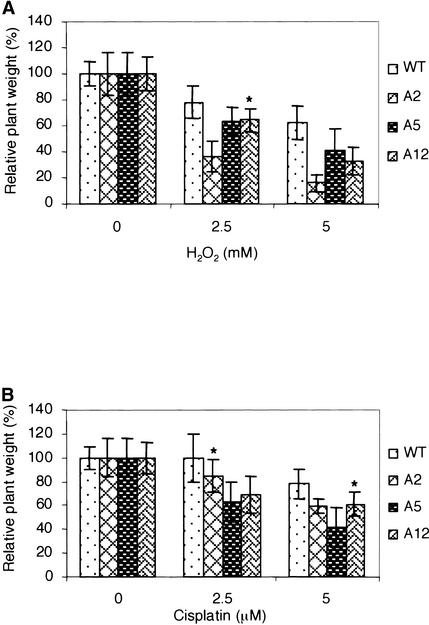

To further characterize the sensitivity of these AtRAD1 antisense plants to DNA-damaging factors, the effect of cisplatin and H2O2 on plant growth was tested in vivo. H2O2 was chosen as an oxidative agent rather than methylene blue because of the light-independent DNA-damaging effect of the former. As shown in Figure 3B, 30 min of irradiation with visible light of plasmid pPP24 in the presence of 10 μg/mL methylene blue caused >50% inhibition of f-luc expression. Therefore, 16 hr of daily illumination in the plant growth chamber was expected to lead to a strong genotoxic effect on the plants, even at low concentrations of methylene blue. The relative growth inhibition caused by the damaging agent is shown in Figure 5; all transgenic lines were less resistant to both cisplatin and H2O2 than were the wild-type plants. The strongest difference was observed for line A2 subjected to oxidative damage (P < 0.001), which agrees with the weakest repair synthesis observed in vitro for the extract obtained from this line (Figure 4). Thus, transgenic Arabidopsis plants downregulated in AtRAD1 activity are ineffective in the repair of UV light– and cisplatin-induced adducts as well as in the repair of oxidative DNA damage both in vitro and in vivo. This result provides strong evidence of the possible involvement of NER enzymes in the repair of oxidative damage in plants. The synergistic effect of the BER/NER mutants on yeast cell survival observed by Swanson et al. (1999) additionally suggests the involvement of BER and NER enzymes in the processing of similar types of DNA lesions.

Figure 5.

Inhibition of Plant Growth by H2O2 and Cisplatin.

Wild-type (WT) and AtRAD1 antisense (A2, A5, and A12) plants were grown on liquid medium containing the indicated concentrations of H2O2 (A) and cisplatin (B). After 10 days, plants were harvested and the weight of each individual plant was measured. Error bars represent standard deviations from 12 independent plants. Asterisks indicate values that are not statistically different from those of the wild type (P > 0.05) using Student's t test.

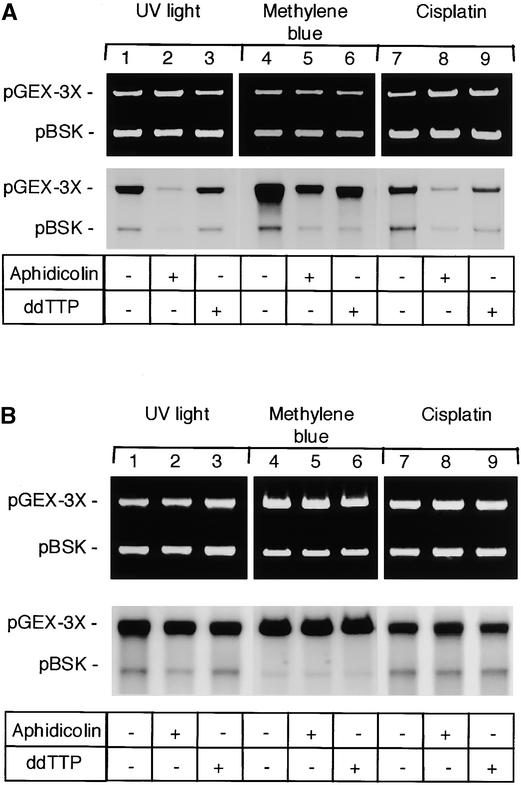

In Vitro Repair Synthesis in Plant Extract Is Not Sensitive to DNA Polymerase Inhibitors

It has been shown in mammalian cells that the gaps in damaged DNA molecules produced in the course of NER and BER are filled in by different DNA polymerases: DNA polymerases ɛ/δ are involved in NER, whereas polymerase β seems to be used for BER (Wood and Shivji, 1997; reviewed by Burgers, 1998). These polymerases differ in their sensitivity to inhibitors; thus, one can distinguish their relative contribution to the repair process (Winters et al., 1999). However, little is known about DNA polymerases in plants in general and about their respective roles in DNA repair in particular. To address this question, we performed an in vitro repair assay in the presence of two DNA polymerase inhibitors: aphidicolin, which is known to be a strong inhibitor of polymerases α, δ, and ɛ, and ddTTP, a specific inhibitor of DNA polymerase β (Winters et al., 1999). As a control, we used a DNA repair–proficient HeLa whole-cell extract. The results shown in Figure 6 indicate that the repair of three differently damaged DNA samples in the control human extract was inhibited strongly by aphidicolin and only slightly by ddTTP, whereas the synthesis in plant extract was not affected to any appreciable extent. As long as there are no clear data about plant DNA polymerases and their role in DNA repair, our results can only suggest that different types of DNA polymerases are recruited during the repair steps of various DNA adducts in plant cells as compared with human ones. The differences observed also may be attributable to the different sensitivity of plant enzymes to the applied inhibitors.

Figure 6.

Effect of DNA Polymerase Inhibitors on in Vitro Repair Synthesis.

(A) HeLa cell extract.

(B) Arabidopsis cell extract.

Standard repair reaction was performed on pGEX-3X DNA damaged by UV light (lanes 1 to 3), methylene blue (lanes 4 to 6), and cisplatin (lanes 7 to 9). Aphidicolin (100 μM) and ddTTP (100 μM) were added where indicated. Nondamaged pBSK DNA was used as a control template.

DISCUSSION

In Vitro Repair Synthesis Assay Monitors NER and BER Efficiently

In the present work, we demonstrate the application of an in vitro repair synthesis assay for the characterization of DNA repair mechanisms in Arabidopsis. We monitored the incorporation of DIG-labeled nucleotides into UV light–damaged DNA. A given UV light dose induces 10 CPDs, 3 6-4-PP, and 1 pyrimidine hydrate in 3 kb of plasmid DNA (Wood et al., 1995). The first two of these, representing the major type of UV light–induced DNA lesions, were repaired by NER under conditions used for our assay to avoid photoreactivation by lyases. Other minor lesions, such as Tg, pyrimidine hydrates, and 8-oxoG, represent only a small proportion of UV light–induced damage and are believed to be substrates for BER short patch repair. These lesions are unlikely to alter noticeably the final repair synthesis signal, although BER intermediates themselves often are targets for other types of repair (Lindahl and Wood, 1999; Memisoglu and Samson, 2000). Nevertheless, to distinguish between the mechanisms that may be involved in the repair synthesis that we observed in UV light–damaged DNA, we needed to discriminate between NER and BER. Therefore, we used cisplatin- and methylene blue–treated DNA as model substrates for NER and BER, respectively, compared with UV light–damaged DNA.

The strong incorporation of DIG label into methylene blue–damaged DNA, compared with UV light–damaged DNA, indicated efficient repair of oxidative damage by the plant extracts used (Figure 2B). Similar results were obtained when the repair of UV light–irradiated and methylene blue–treated DNA extract was compared in a HeLa cell extract (Jaiswal et al., 1998). In another comparative study of in vitro excision by a rodent cell extract and a system reconstituted from purified human factors, 8-oxoG was excised 1.5 to 2 times faster than CPD (Reardon et al., 1997). The relatively weak repair of platinated DNA compared with UV light–irradiated DNA (Figure 2B) is consistent with previously reported observations with mammalian extracts (Szymkowski et al., 1992). The fact that the highest repair activity was observed for methylene blue–damaged DNA and the lowest repair activity was observed for cisplatin-damaged DNA suggests different repair pathways and/or different kinetics of repair. It is interesting that photolyase, which is known to be present and very efficient in plants but not active in our assay conditions, binds to cisplatin-damaged DNA with high affinity in yeast and inhibits NER of cisplatin adducts (Fox et al., 1994). Also, human replication protein A, which is implicated in the damage recognition step of NER, exhibits 50-fold preferential binding to 6-4-PP (Burns et al., 1996) and only a 10- to 20-fold binding capacity to platinated DNA substrates compared with nondamaged control DNA (Patrick and Turchi, 1998).

If we assume that platinated DNA is repaired exclusively by NER, UV light–irradiated plasmid is repaired mainly by NER, and 8-oxoG induced by methylene blue treatment is a substrate for BER, the repair synthesis that we detected could be assigned to the cumulative impact of both repair pathways. However, there is some evidence that in mammalian and yeast cells, NER can be involved partially in the repair of oxidative damage (Reardon et al., 1997; Torres-Ramos et al., 2000). It was shown that 8-oxoG can be repaired efficiently by a human cell extract, and some NER-deficient mutants exhibit deficiency in this repair. From these results, NER involvement in the repair of oxidative damage has been proposed (Jaiswal et al., 1998). Extrapolated to our system, this may mean that the NER pathway is used for both types of DNA lesions. In other work, Tg and 8-oxoG oxidative lesions were used as substrates for an in vitro excision assay in human and rodent whole-cell extracts compared with classic NER substrate (CPDs). Both Tg and 8-oxoG adducts were excised efficiently in a wild-type extract, whereas extracts from cells deficient in NER were unable to excise Tg and 8-oxoG as well as CPD (Reardon et al., 1997). The same efficient excision of oxidatively damaged nucleotides was observed in the in vitro system reconstituted from purified human NER factors. Therefore, the authors considered the removal of these nonbulky oxidative lesions by NER to be physiologically relevant in mammals (Reardon et al., 1997).

A role for NER enzymes in the BER pathway was suggested by Klungland et al. (1999). They have shown that the XPG protein promotes the binding of the hNth1 protein (the human counterpart of Escherichia coli endonuclease III) to oxidatively damaged DNA and that stimulation of hNth1 activity is retained in XPG catalytic site mutants inactive in NER. Recently, further evidence for a possible overlap of different repair pathways was reported for S. cerevisiae. A yeast triple mutant deficient in the BER enzymes N-glycosylase and alkaline phosphatase lyase was not sensitive to oxidizing agents, suggesting an involvement of another glycosylase or another repair pathway. However, when the NER enzyme RAD1 was disrupted in this triple mutant, the cells became highly sensitive to H2O2 and menadione (Swanson et al., 1999). Similarly, disruption of rad1 or rad10 in yeast mutants deficient in BER significantly increased their sensitivity to damage by methyl methanesulfonate (Xiao and Chow, 1998).

In Vitro Repair by Plant Extracts with Reduced RAD1 Activity

Our results showed that transgenic Arabidopsis plants downregulated in endogenous RAD1 activity by an antisense strategy are less efficient in the repair of cisplatin- and UV light–induced lesions (Figure 4), proving their NER deficiency. However, because these lines also are impaired in the repair of methylene blue–induced adducts, the direct or indirect involvement of NER enzymes in oxidative damage repair also is indicated. The possible relevance of the overlap of two DNA repair pathways in vivo was demonstrated by the increased sensitivity of these antisense plants to H2O2 (Figure 5A). All transgenic lines exhibited an increased sensitivity to cisplatin compared with the sensitivity of the wild-type plants, in accordance with their NER deficiency. Although the differences are not drastic, in most cases they are statistically significant and resemble the moderate sensitivity of these lines to UV light (Gallego et al., 2000). The fact that these AtRAD1 transgenic lines, especially A2, are less resistant to H2O2 reconfirms the observed impairment in oxidative lesion repair in vitro (Figure 4). Although H2O2 induces a broad spectrum of DNA lesions, the most abundant products are 2,6-diamino-4-hydroxy-5-formamidopyrimidine and 8-oxoG (Jaruga and Dizdaroglu, 1996), both of which are repaired mainly by BER in human cells. Thus, our observations demonstrated that downregulation of AtRAD1 affects the repair of oxidative damage by an unknown mechanism.

Plant Polymerases Involved in BER and NER Are Not Inhibited by Aphidicolin and ddTTP

An indication that DNA repair processes in plant cells may be different from the classic animal model of NER and BER is provided by the experiment with DNA polymerase inhibitors (Figure 6). In mammalian cells, a 24- to 32-nucleotide gap resulting from the excision of a damaged DNA segment during NER was filled by polymerase δ/ɛ, whereas polymerase β was primarily responsible for the repair synthesis in BER (reviewed by Wood and Shivji, 1997; Burgers, 1998). Additionally, DNA polymerases δ and ɛ have been shown to contribute to BER in mammalian (Frosina et al., 1996) and amphibian (Matsumoto et al., 1994) cells.

The strong effect of aphidicolin on the repair of UV light–irradiated and platinated DNA observed with the control HeLa whole-cell extract (Figure 6) is in good agreement with the involvement of polymerases δ/ɛ in the NER pathway. However, the more pronounced inhibition of methylene blue–damaged DNA repair by aphidicolin compared with ddTTP was not expected because of the current assumption that oxidative damage is repaired by BER involving polymerase β. Interestingly, Jaiswal et al. (1998) observed a very similar rate of inhibition of repair synthesis on methylene blue–treated DNA in HeLa cell extracts (40% inhibition by aphidicolin and 1% inhibition by ddTTP). On the basis of this result, the authors also suggested the involvement of different pathways in the repair of oxidative damage (Jaiswal et al., 1998).

Unfortunately, there is very limited information about plant DNA polymerases and their possible roles in DNA repair. Four different DNA polymerases, designated A, B, C1, and CII, were purified from wheat embryos and were described as homologous with human polymerases based on their biochemical properties, sensitivity to inhibitors, and expression patterns. Polymerase A was proposed to be the plant analog of animal polymerase α, polymerases B and CII were proposed to be the plant homologs of polymerase δ, and polymerase C1 was proposed to be the counterpart of polymerase β (Richard et al., 1991; Laquel et al., 1993; Benedetto et al., 1996; Luque et al., 1998). The activities of some of these proteins were inhibited by aphidicolin (polymerase B) or ddTTP (wheat DNA polymerase C1).

Clear in vivo functional activity has not been shown for all of the plant polymerases mentioned above; thus, we cannot functionally interpret our result that repair synthesis in plant extracts was not affected to any significant extent by aphidicolin or ddTTP. Because our results indicate a possible overlap between different repair pathways in plants, we cannot exclude the involvement of various DNA polymerases in the repair process, including those that are not sensitive to the inhibitors we used. The presence of multiple DNA polymerase activities in plants also could indicate an efficient compensation of the inhibited enzyme by other polymerases insensitive to the applied drug, as has been reported in S. cerevisiae (Wang et al., 1993; Budd and Campbell, 1995). On the other hand, it cannot be excluded that the orthologous polymerases in plants and animals have different sensitivities to the applied inhibitors.

Outlook

The in vitro repair synthesis system described in our work allows reliable monitoring of NER, a process that is understood poorly in plants. This conclusion is based on the following observations: (1) strong damage-dependent synthesis was detected with cisplatin-treated DNA, a lesion that is repaired exclusively by NER in human cells, and with UV light–irradiated DNA, which contains mainly pyrimidine dimers, a substrate for NER; and (2) extracts derived from plants downregulated in the AtRAD1 NER enzyme were ineffective in this assay. The efficient repair detected for methylene blue–damaged DNA may indicate that we also recorded BER activity. However, the lower proficiency to repair this type of damage by AtRAD1-depleted transgenic plants suggests the possible involvement, either direct or indirect, of NER enzymes in the repair of oxidative damage in plants. This hypothesis also is supported by the increased sensitivity of these plants to oxidative stress. Further studies are required to clearly understand the contribution of these different repair strategies to the preservation of plant genome integrity.

METHODS

Plant Material

Sterilized seed from wild-type and homozygous T3 generation AtRAD1 antisense Arabidopsis thaliana plants (Gallego et al., 2000) were plated on 10-cm Petri dishes containing 35 mL of half-strength Murashige and Skoog (1962) medium with vitamins (Duchefa, Haarlem, The Netherlands) and 0.8% Bacto-agar (Becton Dickinson, Oxford, UK) supplemented with 1% sucrose, pH 5.8. The plates were kept for 48 hr at 4°C in the dark to synchronize germination and then transferred to the growth chamber at 23°C with a daily regime of 16 hr of light (Osram L 58W/21, Lumilux Cool White, Osram, Munich, Germany) and 8 hr of dark. After 3 weeks, whole plants including roots were harvested and frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Purification of Plant Cell Extract

All steps were performed at 0 to 4°C. Frozen plant material was ground in a handle mortar with liquid N2, and then the powder was resuspended in 7 volumes (w/v) of ice-cold homogenization buffer containing 25 mM Hepes-KOH, pH 7.8, 100 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 250 mM sucrose, 10% glycerol, 1 mM DTT, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. The homogenate was filtered through a 40-μm nylon mesh and then through a 20-μm nylon mesh and placed on a magnetic stirrer. While being stirred, 2 M KCl was added slowly to a final concentration of 450 mM. After 30 min of extraction, cellular and nuclear debris was removed by centrifugation at 40,000g for 1 hr. The supernatant was transferred to a glass beaker and placed on a magnetic stirrer, and solid (NH4)2SO4 was added slowly to 70% saturation. To neutralize the supernatant, 10 μL of 1 M NaOH was added for each 1 g of (NH4)2SO4. After 1 hr, the precipitated proteins were collected by centrifugation at 20,000g for 1 hr. The supernatant was removed completely, and the pellet was dissolved in the minimal volume of dialysis buffer (25 mM Hepes-KOH, pH 7.8, 100 mM KCl, 12 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 17% glycerol, and 2 mM DTT) and dialyzed overnight against the same buffer. Protein concentration was measured (typically 10 mg/mL), and the extract was frozen in small aliquots in liquid N2 and kept at −80°C.

Repair Substrates

The plasmids used as DNA substrates for repair synthesis were 4.9-kb pGEX-3X (Amersham Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) and 2.96-kb pBluescript II SK+ (Stratagene, Heidelberg, Germany), which were linearized with SmaI (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA). To induce UV light damage, 0.1 mg/mL DNA solution in TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl and 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) was distributed in 10-μL aliquots on a Petri dish, kept on ice, placed in a UV-Stratalinker (λ max = 254 nm; model 1800; Stratagene, Heidelberg, Germany), and irradiated at the doses indicated in figure legends (450 J/m2 for standard assay). Plasmid DNA was separated by electrophoresis on a 0.8% agarose gel without ethidium bromide, and the linear form was excised using the ethidium bromide–stained marker lane as a reference and isolated afterward using the QIAquick GEL Extraction Kit (Qiagen, Basel, Switzerland). Cisplatin treatment was performed by incubation of DNA in 10 mM Hepes-KOH, pH 7.8, in the presence of cisplatin (5 μM for standard reaction) in the dark at 37°C for 18 hr. After incubation, cisplatin was removed by three 70% ethanol precipitation/washing steps. For methylene blue–induced damage, a DNA solution (0.1 mg/mL) in TE buffer was mixed with methylene blue in the dark to give a final concentration of 1, 5, or 10 μg/mL methylene blue and distributed in 10-μL aliquots in 6 × 10 wells sterile microwell plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark). The plate was kept on ice and exposed to light from a 60-W tungsten bulb positioned 15 cm from the surface. After the time indicated in figure legends, methylene blue was removed by three ethanol precipitation/washing steps.

In Vitro Repair Synthesis

The repair reaction was performed as described previously (Wood et al., 1995) with several modifications. Linearized, gel-purified, damaged, and nondamaged plasmid DNAs (300 ng of each) were mixed with buffer containing 50 mM Hepes-KOH, pH 7.8, 40 mM KAc, 8 mM MgAc, 1 mM DTT, 0.4 mM EDTA, 2.5 μg of BSA, 50 μg/mL creatine phosphokinase, 45 mM phosphocreatine, 6% glycerol, 4.8% polyethylene glycol (PEG) 8000, 4 mM ATP, 50 μM dATP, dGTP, and dCTP, 44.4 μM dTTP, and 5.6 μM digoxigenin (DIG)-11-dUTP on ice. Arabidopsis whole-cell extract (50 μg of total protein) was added, and the reaction (total volume of 25 μL) was incubated in the dark at 25°C for 2 hr. The reaction was stopped with 20 mM EDTA, digested with 50 μg/mL RNase A, and treated with 0.2 mg/mL proteinase K in 0.5% SDS, and DNA was extracted with phenol/chloroform as described (Wood et al., 1995). After separation by electrophoresis on a 0.8% agarose gel containing 0.5 μg/mL ethidium bromide, the gel was photographed and DNA was transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Hybond N+; Amersham Pharmacia) by capillary transfer (Sambrook et al., 1989) and detected with the DIG Nucleic Acid Detection Kit (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) using anti-DIG–alkaline phosphatase conjugate and CDP-Star as a chemiluminescence substrate for alkaline phosphatase according to the manufacturer's instructions. HeLa whole-cell extract proficient in nucleotide excision repair was kindly provided by Hanspeter Naegeli and Tonko Buterin, Institute of Pharmacology and Toxicology, University of Zürich, Switzerland.

Transient Expression in Tobacco Protoplasts

Plasmids pPP24 and pRR22 expressing firefly and Renilla luciferase, respectively, were kindly donated by Johannes Fütterer, Institute of Plant Sciences, ETH Zürich, Switzerland. pPP24 damaged and purified as described above and nondamaged pRR22 were used for protoplast transformation. Isolation, polyethylene glycol–mediated transformation of tobacco protoplasts, and preparation of protoplast protein extract were performed as described previously (Bilang et al., 1994). The activity of both luciferases in protoplast protein extract was measured using a luminometer (Lumat LB 9507; EG&G, Berthold, Germany) with the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer. Firefly luciferase activity was standardized against Renilla luciferase activity, which served as an internal control for transformation efficiency, and was expressed as a percentage of the activity of nondamaged pPP24.

Effect of Cisplatin and H2O2 in Vivo

Plant growth was achieved as described (Gallego et al., 2000) for the mitomycin C assay. Briefly, 4-day-old seedlings germinated as described above were transferred onto 24-well plastic plates (Sarstedt, Newton, NC). Each well contained one seedling in 1 mL of liquid half-strength Murashige and Skoog (1962) medium plus 1% sucrose and 2.5 mM Mes, pH 5.8. The medium was supplemented with cisplatin at concentrations of 0, 2.5, and 5 μM or H2O2 at concentrations of 0, 2.5, and 5 mM. The plates were incubated at 23°C (16 hr of light/8 hr of dark) for 10 days, and then the weight of each individual plant was measured. Statistical analysis was performed using Student's t test.

Acknowledgments

The authors are very grateful to Hanspeter Naegeli and Tonko Buterin for providing HeLa cell extract and for useful advice and to Johannes Fütterer for providing pPP24 and pRR22 plasmid and for critical discussion. The authors are thankful to Barbara Hohn and Lisa Valentine for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by Swiss National Science Foundation for Scientific Research Grant No. 31-51'077.97.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1105/tpc.010258.

References

- Aboussekhra, A., Biggerstaff, M., Shivji, M.K.K., Vilpo, J.A., Moncollin, V., Podust, V.N., Protić, M., Hübscher, U., Egly, J.-M., and Wood, R.D. (1995). Mammalian DNA nucleotide excision repair reconstituted with purified components. Cell 80, 859–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedetto, J.P., Ech-Chaoui, R., Plissonneau, J., Laquel, P., Litvak, S., and Casroviejo, M. (1996). Changes of enzymes and factors involved in DNA synthesis during wheat germ germination. Plant Mol. Biol. 31, 1217–1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilang, R., Klöti, A., Schrot, M., and Potrykus, I. (1994). PEG-mediated direct gene transfer and electroporation. Plant Mol. Biol. Manual A1, 1–16.

- Britt, A.B. (1999). Molecular genetics of DNA repair in higher plants. Trends Plant Sci. 4, 20–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd, M.E., and Campbell, J.L. (1995). DNA polymerases required for repair of UV-induced damage in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15, 2173–2179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgers, P.M. (1998). Eukaryotic DNA polymerases in DNA replication and DNA repair. Chromosoma 107, 218–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns, J.L., Guzder, S.N., Sung, P., Prakash, S., and Prakash, L. (1996). An affinity of human replication protein A for ultraviolet-damaged DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 11607–11610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu, G. (1994). Cellular response to cisplatin: The roles of DNA-binding proteins and DNA repair. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 787–790. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demple, B., and Harrison, L. (1994). Repair of oxidative damage to DNA: Enzymology and biology. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 63, 915–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fidantsef, A.L., Mitchell, D.L., and Britt, A.B. (2000). The Arabidopsis uvh1 gene is a homolog of the yeast repair endonuclease RAD1. Plant Physiol. 124, 579–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox, M.E., Feldman, B.J., and Chu, G. (1994). A novel role for DNA photolyase: Binding to DNA damaged by drugs is associated with enhanced cytotoxicity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14, 8071–8077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedberg, E.C. (1996). Relationship between DNA repair and transcription. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 65, 15–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frosina, G., Fortini, P., Rossi, O., Carrozzino, F., Raspaglio, G., Coxi, L.S., Lanei, D.P., Abbondandolo, A., and Dogliotti, E. (1996). Two pathways for base excision repair in mammalian cells. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 9573–9578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallego, F., Fleck, O., Li, A., Wyrzykowska, J., and Tinland, B. (2000). AtRAD1, a plant homologue of human and yeast nucleotide excision repair endonucleases, is involved in dark repair of UV damages and recombination. Plant J. 21, 507–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamper, H.B., Parekh, H., Rice, M.C., Bruner, M., Youkey, H., and Kmiec, E.B. (2000). The DNA strand of chimeric RNA/DNA oligonucleotides can direct gene repair/conversion activity in mammalian and plant cell-free extracts. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 4332–4339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He, Z., Wong, J.M.S., Maniar, H.S., Brill, S.J., and Ingles, C.J. (1996). Assessing the requirements for nucleotide excision repair proteins of Saccharomyces cerevisiae in an in vitro system. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 28243–28249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaiswal, M., Lipinski, L.J., Bohr, V.A., and Mazur, S.J. (1998). Efficient in vitro repair of 7-hydro-8-oxoguanosine by human cell extracts: Involvement of multiple pathways. Nucleic Acids Res. 26, 2184–2191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaruga, P., and Dizdaroglu, M. (1996). Repair products of oxidative DNA base damage in human cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 24, 1389–1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klungland, A., Hoess, M., Gunz, D., Constantinou, A., Clarkson, S.A., Doetsch, P.W., Bolton, P.H., Wood, R.D., and Lindahl, T. (1999). Base excision repair of oxidative DNA damage activated by XPG protein. Mol. Cell 3, 33–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laat, W., Jaspers, L., and Hoeijmakers, H. (1999). Molecular mechanism of nucleotide excision repair. Genes Dev. 13, 768–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laquel, P., Litvak, S., and Castroviejo, M. (1993). Mammalian proliferating cell nuclear antigen stimulates the processivity of two wheat embryo DNA polymerases. Plant Physiol. 102, 107–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Page, F., Kwoh, E., Avrutskaya, A., Gentil, A., Leadon, S., Sarasin, A., and Cooper, P. (2000). Transcription-coupled repair of 8-oxoguanine: Requirement for XPG, TFIIH, and CSB and implications for Cockayne syndrome. Cell 101, 159–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindahl, T., and Wood, R.D. (1999). Quality control by DNA repair. Science 286, 1897–1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z., Hossain, G.Z., Islas-Osuna, M.A., Mitchell, D.L., and Mount, D.W. (2000). Repair of UV damage in plants by nucleotide excision repair: Arabidopsis uvh1 DNA repair gene is a homolog of Saccharomyces cerevisiae RAD1. Plant J. 21, 519–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luque, E., Benedetto, J.P., and Castroviejo, M. (1998). Wheat DNA polymerase C1: A homologue of rat polymerase beta. Plant Mol. Biol. 38, 647–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto, Y., Kim, K., and Bogenhagen, D.F. (1994). Proliferating cell nuclear antigen–dependent abasic site repair in Xenopus laevis oocytes: An alternative pathway of base excision repair. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14, 6187–6197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLennan, A.G. (1987). DNA damage, repair and mutagenesis. In DNA Replication in Plants, J.A. Bryant and V.L. Dunham, eds (Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press), pp. 135–186.

- Memisoglu, A., and Samson, L. (2000). Base excision repair in yeast and mammals. Rev. Mutat. Res. 451, 39–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murashige, T., and Skoog, F. (1962). A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue culture. Physiol. Plant. 15, 473–497. [Google Scholar]

- Patrick, S.M., and Turchi, J.J. (1998). Human replication protein A preferentially binds cisplatin-damaged duplex DNA in vitro. Biochemistry 37, 8808–8815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash, S., and Prakash, L. (2000). Nucleotide excision repair in yeast. Mutat. Res. 451, 13–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reardon, J.T., Bessho, T., Kung, H.C., Bolton, P.H., and Sancar, A. (1997). In vitro repair of oxidative damage by human nucleotide repair system: Possible explanation for neurodegeneration in Xeroderma pigmentosum patients. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 9463–9468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice, M.C., May, G.D., Kipp, P.B., Parekh, H., and Kmiec, E.B. (2000). Genetic repair of mutations in plant cell-free extracts directed by specific chimeric oligonucleotides. Plant Physiol. 123, 427–437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard, M.C., Litvak, S., and Castroviejo, M. (1991). DNA polymerase B from wheat embryos: A plant delta-like DNA polymerase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 287, 141–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook, J., Fritsch, E.F., and Maniatis, T. (1989). Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 2nd ed. (Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press).

- Sancar, A. (1996). DNA excision repair. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 65, 43–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, J.E., Price, S., Maidt, L., Gutteridge, J.M.C., and Floyd, R.A. (1990). Methylene blue plus light mediates 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine formation in DNA preferentially over strand breakage. Nucleic Acids Res. 18, 631–635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson, R.L., Morey, N.J., Doetsch, P.W., and Jinks-Robertson, S. (1999). Overlapping specificities of base excision repair, nucleotide excision repair, recombination, and translesion synthesis pathways for DNA base damage in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 2929–2935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szymkowski, D.E., Yarema, K., Essigmann, J.M., Lippard, S.J., and Wood, R. (1992). An intrastrand d(GpG) platinum cross link in duplex M13 is refractory to repair by human cell extract. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89, 10772–10776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Ramos, C.A., Johnson, R.E., Prakash, L., and Prakash, S. (2000). Evidence for the involvement of nucleotide excision repair in the removal of abasic sites in yeast. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 3522–3528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vonarx, E.J., Mitchell, H.L., Karthikeyan, R., Chatterjee, I., and Kunz, B.A. (1998). DNA repair in higher plants. Mutat. Res. 400, 187–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z., Wu, X., and Friedberg, E.C. (1993). DNA repair synthesis during base excision repair in vitro is catalyzed by DNA polymerase ɛ and is influenced by DNA polymerases α and δ in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13, 1051–1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z., Wu, X., and Friedberg, E.C. (1995). The detection and measurement of base and nucleotide excision repair in cell-free extracts of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Methods Enzymol. 7, 177–186. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z., Wu, X., and Friedberg, E.C. (1996). A yeast whole cell extract supports nucleotide excision repair and RNA polymerase II transcription in vitro. Mutat. Res. 364, 33–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winters, T.A., Russell, P.S., Kohli, M., Dar, M.E., Neumann, R.D., and Jorgensen, T.J. (1999). Determination of human DNA polymerase utilization for the repair of a model ionizing radiation-induced DNA strand break lesion in a defined vector substrate. Nucleic Acids Res. 27, 2423–2433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood, R.D. (1996). DNA repair in eukaryotes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 65, 135–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood, R.D., and Shivji, M.K. (1997). Which DNA polymerases are used for DNA repair in eukaryotes? Carcinogenesis 18, 605–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood, R.D., Robins, P., and Lindahl, T. (1988). Complementation of the Xeroderma pigmentosum DNA repair defect in cell-free extracts. Cell 53, 97–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood, R.D., Biggerstaff, M., and Shivji, M.K.K. (1995). Detection and measurement of nucleotide excision repair synthesis by mammalian cell extracts in vitro. Methods Enzymol. 7, 163–175. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, W., and Chow, B.L. (1998). Synergism between yeast nucleotide and base excision repair pathways in the protection against DNA methylation damage. Curr. Genet. 33, 92–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You, Z., Feaver, W.J., and Friedberg, E.C. (1998). Yeast RNA polymerase II transcription in vitro is inhibited in the presence of nucleotide excision repair: Complementation of inhibition by holo-TFIIH and requirement for RAD26. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18, 2668–2676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamble, D.B., and Lippard, S.J. (1995). Cisplatin and DNA repair in cancer chemotherapy. Trends Biochem. Sci. 20, 435–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlatanova, J., Yaneva, J., and Leuba, S. (1998). Proteins that specifically recognize cisplatin-damaged DNA: A clue to anticancer activity of cisplatin. FASEB J. 12, 791–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]