Abstract

The eds5 mutant of Arabidopsis (earlier named sid1) was shown previously to accumulate very little salicylic acid and PR-1 transcript after pathogen inoculation and to be hypersusceptible to pathogens. We have isolated EDS5 by positional cloning and show that it encodes a protein with a predicted series of nine to 11 membrane-spanning domains and a coil domain at the N terminus. EDS5 is homologous with members of the MATE (multidrug and toxin extrusion) transporter family. EDS5 expression is very low in unstressed plants and strongly induced by pathogens and UV-C light. The transcript starts to accumulate 2 hr after inoculation of Arabidopsis with an avirulent strain of Pseudomonas syringae or UV-C light exposure, and it stays induced for ∼2 days. EDS5 also is expressed after treatments with salicylic acid, indicating a possible positive feedback regulation. EDS5 expression after infection by certain pathogens as well as after UV-C light exposure depends on the pathogen response proteins EDS1, PAD4, and NDR1, indicating that the signal transduction pathways after UV-C light exposure and pathogen inoculation share common elements.

INTRODUCTION

Plants react to an attack by phytopathogenic microorganisms with an array of inducible defense responses. Whether a plant is resistant or susceptible to a potential pathogen depends largely on how fast a pathogen is recognized and defense responses are activated. For instance, in gene-for-gene resistance, the product of an avirulence gene of the pathogen is recognized by a corresponding resistance gene product of the plant, leading to the rapid activation of various defense responses. Such a pathogen is avirulent to the plant, its invasion can be stopped, and the plant is resistant. Disease ensues when the pathogen is not recognized rapidly and defense mechanisms are activated too slowly to stop the infection process. In this case, the pathogen is virulent and the plant is susceptible. In addition, defense responses can be induced systemically in all parts of the plant by pathogens, soil-borne microorganisms, chemicals, or certain forms of stress. This form of induced resistance is referred to as systemic acquired resistance (Ryals et al., 1994; Sticher et al., 1997).

Salicylic acid (SA) is synthesized after inoculation of plants with pathogens or exposure to certain abiotic stresses, such as ozone and UV-C light. SA was found to be essential for gene-for-gene resistance, systemic acquired resistance, and reduction of disease development after inoculation with virulent pathogens (Delaney et al., 1994; Nawrath and Métraux, 1999).

In Arabidopsis, the elucidation of the signal transduction pathway downstream of SA leading to the expression of a number of pathogenesis-related (PR) proteins, such as PR-1, PR-2, and PR-5, has been centered on the characterization of the npr1/nim1 mutant (Cao et al., 1994; Delaney et al., 1995). The npr1/nim1 mutant does not express PR-1, PR-2, and PR-5 after treatment with SA analogs, such as isonicotinic acid (Cao et al., 1994; Delaney et al., 1995). However, when infected with pathogens such as Pseudomonas syringae pv maculicula, only PR-1 expression is reduced strongly, indicating that pathogens may induce PR-2 and PR-5 in a NPR-independent manner (Glazebrook et al., 1996). The NPR1/NIM1 gene encodes a novel protein with ankyrin repeats (Cao et al., 1997; Ryals et al., 1997) that is translocated to the nucleus upon SA treatment (Kinkema et al., 2000). NPR1/NIM1 likely acts as a transcriptional coactivator that enhances the binding of basic leucine zipper protein transcription factors of the TGA family to the as1 element of the PR-1 promoter (Zhang et al., 1999; Zhou et al., 2000).

Several mutants of Arabidopsis have been isolated that are unable to establish defense responses (Glazebrook, 1999). NDR1, a small membrane-associated protein, is essential for the establishment of resistance after inoculation with certain avirulent pathogens, such as P. syringae carrying the avrRpt2 or avrRpm1 gene. In this case, effective activation of defense depends on resistance genes containing a nucleotide binding site and a leucine-rich repeat domain (Century et al., 1995, 1997). EDS1, a protein with homology with lipases, is necessary for activation of the defense pathway after inoculation with virulent and certain avirulent pathogens, such as P. syringae carrying the avrRps4 gene (Parker et al., 1996; Aarts et al., 1998; Falk et al., 1999; Feys and Parker, 2000). PAD4 also contains a lipase domain (Glazebrook et al., 1997; Jirage et al., 1999) and is required for the activation of the SA-dependent defense pathway, the production of the phytoalexin camalexin, and the reduction of disease development after inoculation with virulent P. syringae and virulent as well as avirulent Peronospora parasitica isolates (Glazebrook et al., 1997; Zhou et al., 1998).

The eds5/sid1 (eds5 is allelic to sid1) (Rogers and Ausubel, 1997; Nawrath and Métraux, 1999) and sid2 mutants of Arabidopsis do not accumulate SA after inoculation with either virulent or avirulent pathogens or after abiotic stresses and demonstrate strongly reduced expression of PR-1. Both mutants display pathogen-induced increases in PR-2 and PR-5 expression, similar to that observed in the npr1/nim1 mutant (Glazebrook et al., 1996), and accumulate high levels of camalexin (Nawrath and Métraux, 1999; Dewdney et al., 2000). In contrast, SA-degrading NahG plants, despite endogenous SA levels as low as those in eds5 and sid2, show strong reduction in PR-1, PR-2, and PR-5 expression as well as reduced camalexin accumulation after pathogen inoculation (Delaney et al., 1995; Zhao and Last, 1996). The susceptibility to pathogens of the eds5 and sid2 mutants is intermediate between that of wild-type and NahG plants (Nawrath and Métraux, 1999). Here, we describe the isolation of the EDS5 gene by positional cloning. The predicted protein is a membrane protein that shows homology with MATE (multidrug and toxin extrusion) transporters.

RESULTS

Identification and Characterization of the EDS5 Gene

EDS5 was mapped ∼2 centimorgan (cM) from the simple sequence length polymorphism (SSLP) marker nga1107 (Nawrath and Métraux, 1999). Analysis of 48 eds5 plants selected from a Landsberg erecta (Ler) × eds5 F2 population identified the SSLP markers F20D10-45.5 and F23K16-28.4 as the closest markers flanking the eds5 mutation on each side. Screening of 1060 randomly chosen plants from a Ler × eds5-3 F2 mapping population with the SSLP markers F20D10-45.8 and F23K16-28.4 identified 39 plants having a recombination in the interval. By using these 39 recombinant plants, EDS5 was found to be located 0.38 cM from nga1107 and 0.2 cM from CCR1. By using additional markers, EDS5 was positioned at an equal distance of 0.09 cM between two SSLP markers located at positions 49.5 and 79.3 kb of the bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) F19H22, defining a 30-kb interval. Four of six genes present on the annotated sequence of the 30-kb region of BAC F19H22 were examined by RNA gel blot analysis. Gene 130 (At4 g39030) was identified as the putative EDS5, because this gene was pathogen inducible and showed a lower transcription level in all eds5 mutant alleles compared with wild-type plants, as shown below. An overview of the mapping strategy is given in Figures 1A and 1B.

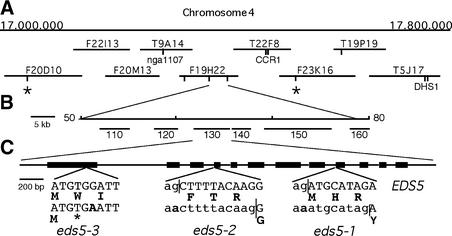

Figure 1.

Positional Cloning and Structure of EDS5.

(A) Region of 800 kb on the bottom of chromosome 4 with overlapping BACs. Positions of known cleaved amplified polymorphic sequence and SSLP markers used for mapping are indicated. Positions of SSLP markers developed for this work from sequence data are labeled by vertical lines. Flanking markers used for the screening of recombinations in 2120 chromosomes are marked by asterisks.

(B) Location of EDS5 on the sequenced BAC clone F19H22. EDS5 was positioned at an equal distance of 0.09 cM between two SSLP markers located at positions 49.5 and 79.3 kb of BAC F19H22. Annotated genes are indicated by their numbers.

(C) Exon/intron structure of EDS5. The coding regions are indicated with thick lines. The inserts present the nucleotide exchanges and their influence on the protein sequences of all three mutant alleles indicated below the wild-type sequence. Lowercase letters mark intron sequences, uppercase letters indicate exon sequences, boldface letters mark amino acids, and the asterisk indicates a stop codon. Splice junctions are indicated by vertical lines.

To identify the structure of the EDS5 gene, a 1.4-kb fragment was amplified by reverse transcriptase–mediated polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) according to the annotated sequence of gene F19H22.130 (At4 g39030). Direct sequencing of the RT-PCR product identified an additional intron at the 3′ end of the gene, indicating that the end of the coding region had not yet been identified. Four additional introns were identified using an internal forward primer close to the predicted end and several reverse primers designed from the genomic sequence. The stop codon and 250 bp of the 3′ untranslated region of EDS5 were characterized with a reverse primer positioned 780 bp downstream of the annotated stop codon of the F19H22.130 gene. The 5′ untranslated region was characterized by RT-PCR using primers at positions −100, −150, −220, and −320 bp from the putative ATG start site. Products of the expected lengths were obtained in all reactions, except when using the primer at −320 bp, which did not result in any RT-PCR product. The ATG of F19H22.130 is the correct start of EDS5 translation because it is the first start codon resulting in an open reading frame and stop codons are present in all three reading frames of the transcript before this ATG. In agreement with the sequence data, a transcript of ∼2.0 kb was identified by RNA gel blot analysis. Thus, the EDS5 gene consists of a gene spanning a 3.4-kb genomic sequence with 12 exons and 11 introns (Figure 1C) and an open reading frame of 1632 bp encoding a protein of 543 amino acids (Figure 2).

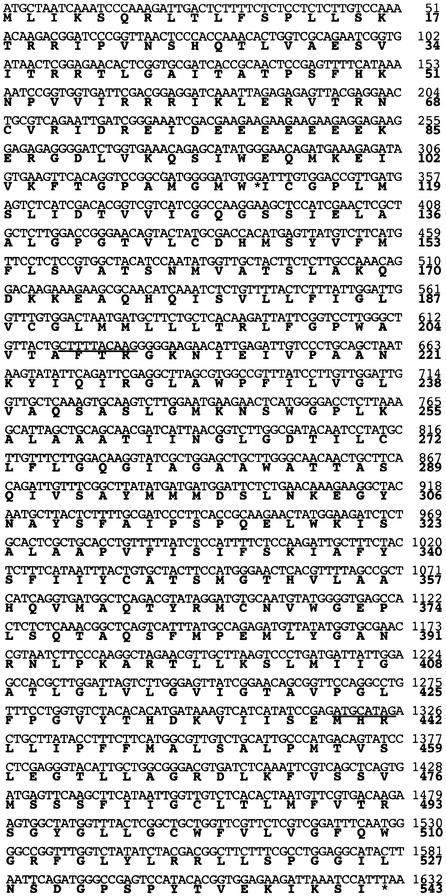

Figure 2.

cDNA Sequence of EDS5 and the Corresponding Protein Sequence.

The amino acid sequence is indicated below the nucleotide sequence in boldface letters. Deletions caused by mutations in the slice acceptor sites in introns 8 and 3 of alleles eds5-1 and eds5-2, respectively, are underlined. The G-to-A transition in nucleotide 339 changing the codon TGG to TGA in eds5-3 is indicated by an asterisk.

The mRNAs of the three mutant alleles of EDS5 were sequenced. As indicated in Figures 1C and 2, eds5-1 and eds5-2 carry short deletions of 8 and 10 bp in the cDNA as a result of abnormal splicing at the border of intron 8/exon 9 and intron 3/exon 4, respectively, resulting in a frameshift and a premature stop codon. These changes are caused by a G-to-A transition in the AG from the splice acceptor site in intron 8 and intron 3, respectively. The eds5-3 allele carries a transition mutation converting a TGG to a premature stop codon (TGA) at nucleotide 339 of the coding region. The changes in all three alleles lead to nonsense mutations. The reduction in transcript accumulation that was observed by RNA gel blot analysis (see below) therefore might have been caused by a nonsense-mediated RNA decay system (Hentze and Kulozik, 1999).

Finally, the identity of EDS5 was tested by complementation analysis. The eds5-3 mutant was transformed with a 4.4-kb (pEDS5-1) or 4.6-kb (pEDS5-2) genomic sequence of the wild type, which included 970 or 830 bp, respectively, upstream of the ATG and 200 bp downstream of the stop codon. Of six independent lines transformed with pEDS5-1 or pEDS5-2, all but one showed complementation of the eds5 mutant phenotype to wild-type or nearly wild-type amounts of SA after pathogen inoculation. A detailed analysis of two representative lines of transgenic plants carrying pEDS5-1 or pEDS5-2 is shown in Figure 3. In addition to increased amounts of SA, these plants also showed a reduced level of camalexin that was even slightly lower than in wild-type plants and increased expression of PR-1 (Figure 3). The eds5-3 plants complemented with the wild-type EDS5 gene were not significantly different from wild type in any of the phenotypes identified previously in the eds5 mutant (Nawrath and Métraux, 1999).

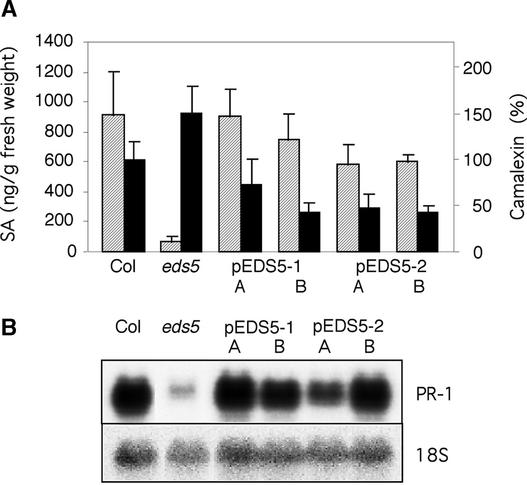

Figure 3.

Complementation of eds5.

SA and camalexin accumulation (A) and PR-1 transcript accumulation (B) from two independent transgenic eds5-3 plants harboring plasmid pEDS5-1 or pEDS5-2, respectively (pEDS5-1 A and B, pEDS5-2 A and B) were analyzed compared with wild type and eds5-3. Plants were inoculated with P. syringae carrying the avrRpt2 gene and analyzed 2 days after inoculation.

(A) SA accumulation is shown in a striped pattern (left scale), and camalexin accumulation is shown in black (right scale); each bar represents the mean and standard error of four to six replicate samples. Camalexin amounts were measured relative to wild type (Col is equal to 100%).

(B) An 18S rDNA probe was used to evaluate uniform loading of RNA. The experiment was repeated once with similar results.

EDS5 Belongs to the MATE Family of Transporters

BLAST analyses with the full-length EDS5 sequence indicate a significant homology of EDS5 with DINF (DNA damage–inducible gene F) of Escherichia coli. DinF is induced by treatments with DNA damage–inducing agents, such as UV-C light (Kenyon and Walker, 1980). However, the DINF function has not yet been identified (Walker, 1995; G.C. Walker, personal communication). Recently, DINF was shown to be homologous with NorM of Vibrio parahaemolyticus (Brown et al., 1999). NorM is the only biochemically characterized member of the MATE protein family, and it has been found to pump antimicrobial agents out of bacterial cells in exchange for sodium (Morita et al., 1998, 2000). A second MATE protein to which a possible transporter function could be assigned is the ethionine resistance protein ERC1 from Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Shiomi et al., 1991; Brown et al., 1999). So far, 56 MATE proteins have been identified in the Arabidopsis genome and are presented in the Arabidopsis membrane protein library (www.cbs.umn.edu./Arabidopsis). Dual sequence alignments with the T-coffee program among EDS5, ERC1, NORM, and DINF showed that all of the proteins share a limited sequence homology, having between 15 and 25% identical amino acids and between 50 and 60% homologous amino acids in the protein part covering the membrane-spanning domains of the protein. Both NORM and DINF are predicted to have 12 transmembrane domains (TMDs), whereas EDS5 and ERC1 have an additional hydrophilic domain at the N terminus. Interestingly, although these N-terminal domains share no explicit sequence homology, both contain stretches rich in glutamic acid (ERC1, 10 Glu in 18 amino acids; EDS5, 9 Glu in 12 amino acids). Further sequence comparisons have been restricted to the region homologous with the TMDs of NORM/DINF. A comparison of EDS5 with DINF and NORM is shown in Figure 4. The homology of EDS5 with DINF was the highest (19% identical, 55% homologous), followed by NORM (18% identical, 53% homologous). The ERC1 of yeast shows a lower homology with EDS5 than with the bacterial proteins (16% identical, 51% homologous), although ERC1 also shows close homology with NORM (22% identity, 69% homologous) and DINF (22% identical, 55% homologous), indicating that ERC1 and EDS5 might have diverged independently from DINF and NORM.

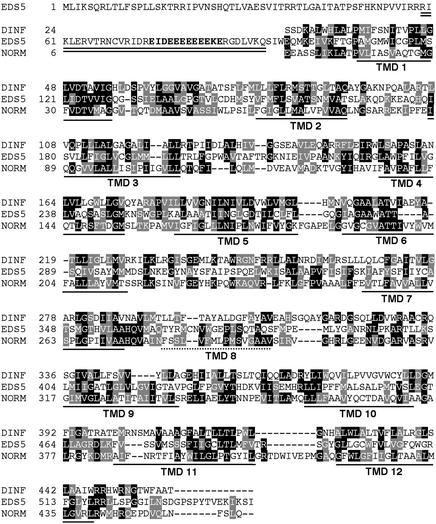

Figure 4.

Analyses of the Predicted Protein Sequence of EDS5.

The double line indicates a predicted coiled-coil structure at the N terminus of the protein. Amino acids of a characteristic Glu stretch are indicated in boldface letters. Sequence comparisons of the EDS5 protein with the DINF protein of E. coli (amino acids 24 to end) and the NORM protein of V. parahaemolyticus (amino acids 6 to end) are shown over the entire conserved region of EDS5 (amino acids 105 to 543). Invariant amino acids are highlighted in black, and conserved amino acids are highlighted in gray. The locations of the TMDs in EDS5 predicted by the PRED-TMR program are underlined with solid lines. TMD 8 of NORM, which has not been identified in EDS5 by any program, is indicated by a dotted line.

The protein structure of EDS5 is predicted to include a coil domain at the hydrophilic N terminus, whereas the rest of the protein forms nine to 11 membrane-spanning domains (see Methods for the programs used). Program PRED-TMR identified 11 membrane-spanning domains correlating to TMDs 1 to 7 and 9 to 12 in the NORM protein (Pasquier et al., 1999). TMD 8 of NORM was not identified in EDS5 by any program, despite good sequence homology in this region (Figure 4).

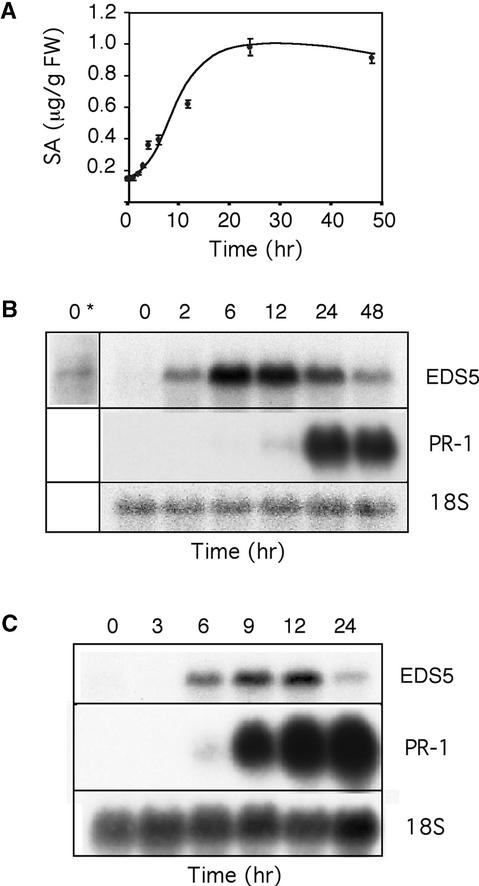

EDS5 Expression and Accumulation of SA after Exposure to UV-C Light

SA has been reported to accumulate after exposure of tobacco to UV-C light (Yalpani et al., 1994). UV-C light also is a good inducer of SA biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Figure 5A shows the accumulation of free SA in Arabidopsis leaves after 20 min of UV-C light exposure. At the start of the experiment, in plants having a low amount of free SA, the expression level of EDS5 also was very low, but detectable, after prolonged exposure to x-ray film (Figures 5A and 5B). The accumulation of free SA started ∼4 hr after the beginning of the UV-C light treatment, increased during the next 8 hr, and stabilized for at least 2 days. Conjugated SA increased in parallel but continued to accumulate even when the amount of free SA did not increase further (data not shown). The EDS5 transcript started to accumulate 1.5 to 2 hr after UV-C light treatment, was maximal after ∼6 hr, and decreased during the next 42 hr (Figure 5B). Thus, the EDS5 transcript increased 2 hr before the first increase in SA was observed, indicating that increased EDS5 expression might be part of the functional mechanism for the induction of SA biosynthesis. In contrast, PR-1 expression started 12 to 24 hr after UV-C light exposure once SA had accumulated to higher levels (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

SA Accumulation and EDS5 Expression after Treatment with UV-C Light and EDS5 Expression after Exogenous Application of SA.

(A) and (B) Accumulation of free SA (A) and expression of EDS5 and PR-1 (B) in Col plants were measured in parallel after UV-C light treatment at the indicated times. In (B), a long-term exposure to x-ray film is indicated by an asterisk. FW, fresh weight.

(C) Col plants were treated by drenching the soil with 0.2 mM Na-SA, and the plants were harvested after the times indicated. Values represent means of three to five measurements ±se from one representative experiment.

In (B) and (C), PR-1 expression was studied in parallel to EDS5 expression. The 18S rDNA probe was used to evaluate uniform loading. The experiments were repeated twice with similar results. For (A), the absolute amounts of the SA accumulated varied somewhat from experiment to experiment, although the general shape of the curve was identical.

Expression of EDS5 after Treatment with SA

The expression of several defense genes, such as PAD4 or EDS1 (Falk et al., 1999; Jirage et al., 1999), has been shown to be regulated by SA. Therefore, we tested the effect of SA on EDS5 expression. Applied either as a soil drench or a leaf spray, SA enhanced EDS5 expression between 6 and 12 hr after treatment followed by a decrease in transcript accumulation (Figure 5C). Thus, as in PAD4 and EDS1, the transcriptional regulation of EDS5 might involve a positive feedback regulation loop by SA.

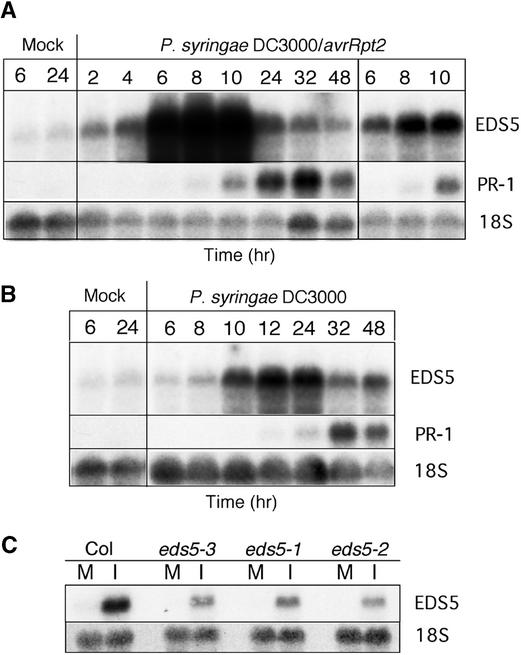

Expression of EDS5 after Inoculation with P. syringae

Inoculation with the avirulent strain of P. syringae carrying the avrRpt2 gene led to an increase in the expression of EDS5 starting 2 hr after pathogen inoculation, reaching a maximum at 8 hr and decreasing slowly during the next 40 hr (Figure 6A). EDS5 was induced earlier than PR-1, whose transcription level began to increase only 6 hr after pathogen inoculation and was maximal between 24 and 32 hr (Figure 6A).

Figure 6.

EDS5 Expression after Pathogen Inoculation.

EDS5 and PR-1 transcript accumulation in wild-type plants at different times after inoculation with an avirulent strain of P. syringae carrying the avrRpt2 gene (A) and after inoculation with the isogenic virulent P. syringae (B). In (A), a short exposure time is shown at right to clarify overexposed parts of the film to the left. (C) shows EDS5 transcript accumulation in wild-type and eds5 mutant alleles 8 hr after inoculation with P. syringae carrying the avrRpt2 gene. The 18S rDNA probe was used to evaluate uniform loading. The experiments were repeated once with similar results. M, mock inoculation; I, pathogen inoculation.

After inoculation with the isogenic virulent strain of P. syringae, transient expression of EDS5 could be observed starting ∼8 hr after inoculation, with a maximum between 12 and 24 hr and decreasing during the next 24 hr (Figure 6B). EDS5 was less induced than after inoculation with the avirulent strain. In comparison, PR-1 expression began to increase only 12 hr after pathogen inoculation and was maximal at ∼32 hr (Figure 6B).

In all three eds5 mutant alleles, the expression level of EDS5 after inoculation with both strains of P. syringae was much lower than in wild-type plants but followed similar kinetics (Figure 6C and data not shown).

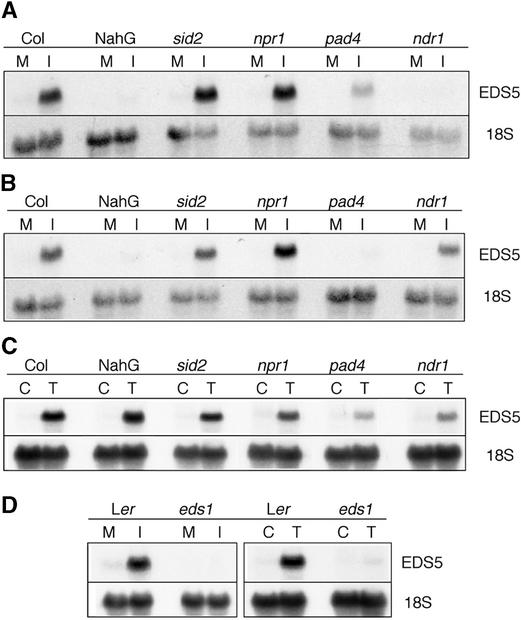

Expression of EDS5 in Mutants Affected in the Disease Resistance Responses after Pathogen Inoculation or UV-C Light Exposure

The expression of EDS5 after inoculation with avirulent and virulent P. syringae strains or UV-C light treatment was further characterized in several mutants affected in their response to pathogens, as presented in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

EDS5 Transcript Accumulation in Different Arabidopsis Mutants.

Mutants in the Col background were inoculated with P. syringae DC3000 pv tomato carrying the avrRpt2 gene (A), with the isogenic virulent strain (B), or exposed to UV-C light (C) and compared with treated Col plants. In (D), the eds1 mutant in the Ler background was inoculated with the isogenic P. syringae strain carrying the avrRps4 gene (left) and was treated with UV-C light (right) and compared with treated Ler plants. The plants were harvested at the time of nearly maximal expression: 8 hr after inoculation with P. syringae carrying the avrRpt2 gene (A) or avrRps4 (D), 24 hr after inoculation with the isogenic virulent P. syringae strain (B), and 7 hr after exposure to UV-C light ([C] and [D]). The 18S rDNA probe was used to evaluate uniform loading. M, mock inoculation; I, pathogen inoculation; C, control; T, UV-C light treatment.

sid2 is a SA induction–deficient mutant with a very similar phenotype to eds5 (Nawrath and Métraux, 1999; Dewdney et al., 2000). The level of expression of EDS5 in sid2 is not significantly different from that of the wild-type plants after inoculation with pathogens (Figures 7A and 7B) or after UV-C light exposure (Figure 7C), showing that SA is not essential for the accumulation of the EDS5 transcript.

Interestingly, the expression of EDS5 is nearly absent in SA-degrading NahG plants (Delaney et al., 1994) 6 and 12 hr after inoculation with avirulent or virulent P. syringae, respectively (Figures 7A and 7B), but it is normal after UV light exposure (Figure 7C). This finding is in sharp contrast to the expression of EDS5 in inoculated sid2 plants. However, 24 and 48 hr after inoculation with P. syringae carrying the avrRpt2 gene, NahG and Columbia expressed EDS5 to approximately the same extent (data not shown). This indicates that NahG plants might display some uncharacterized differences in addition to having very low SA levels, for example, by the unspecific action of the SA hydroxylase on potential signaling compounds other than SA (Cameron, 2000). These hypothetical differences might delay EDS5 accumulation in NahG plants.

The npr1 mutant has a block in the resistance pathway downstream of SA and accumulates higher amounts of SA than wild-type plants after inoculation with P. syringae DC3000 pv tomato carrying the avrRpt2 gene and possibly upregulating SA biosynthesis in a feedback loop (Shah et al., 1997). The npr1 mutation did not influence the expression level of EDS5 significantly after inoculation with this pathogen (Figures 7A and 7B) or UV-C light exposure (Figure 7C). Thus, NPR1 does not affect the control of EDS5 expression.

The pad4 mutant displays low amounts of SA and camalexin as well as enhanced disease susceptibility to the virulent strain of P. syringae DC3000 pv tomato (Glazebrook et al., 1997). EDS5 expression was found to be very low after inoculation with virulent P. syringae (Figure 7A) and reduced after inoculation with avirulent P. syringae (Figure 7B) or exposure to UV-C light (Figure 7C), indicating that PAD4 is involved in the transcriptional regulation of EDS5 after either pathogen inoculation or UV-C light exposure.

The ndr1 mutant is impaired in resistance to P. syringae carrying the avrRpt2 gene and accumulates low levels of SA (Century et al., 1995; A. Shapiro, personal communication). In ndr1, EDS5 gene expression was very low after inoculation with P. syringae carrying avrRpt2, and the induction was reduced after inoculation with the isogenic virulent strain or after UV-C light treatment, indicating that NDR1 also is involved in the transcriptional regulation of EDS5 after either pathogen inoculation or exposure to UV-C light.

The eds1 mutant shows increased susceptibility to P. syringae carrying the avrRps4 gene (Aarts et al., 1998). In eds1, EDS5 gene expression was nearly absent after inoculation with P. syringae carrying the avrRps4 gene as well as after exposure to UV-C light, as shown in Figure 7D. The expression of EDS5 was not altered significantly in the jar1 and etr1 mutants, indicating that EDS5 is not regulated transcriptionally by the ethylene/jasmonate pathway after inoculation with pathogens or UV-C light exposure (data not shown).

Thus, PAD4, EDS1, and NDR1, which are believed to act early in the response to pathogens (Glazebrook, 1999), are involved in the regulation of EDS5 transcription after pathogen inoculation as well as after exposure to UV-C light, indicating that the signaling pathways share common elements. A particularly strong reduction in EDS5 expression was observed in these mutants after inoculation with a pathogen strain to which the respective mutant has enhanced susceptibility. Thus, this reduction can be seen in pad4 inoculated with the virulent P. syringae strain or in ndr1 inoculated with P. syringae carrying avrRpt2. EDS5 expression is independent of SID2 and NPR1, which are in the SA-dependent pathogen response pathway as well as in the ethylene and jasmonate response pathways.

DISCUSSION

To characterize the biosynthesis of SA, we have used a mutational approach whereby Arabidopsis plants infected with an avirulent P. syringae were screened for their inability to accumulate SA. This led to the discovery of two mutants, sid1 (allelic to eds5; Rogers and Ausubel, 1997) and sid2, both of which are characterized by low levels of SA, low PR-1 expression, and enhanced disease susceptibility after infection (Nawrath and Métraux, 1999). Therefore, EDS5 encodes a protein with an essential function in the SA-dependent pathway of plant defense against pathogens.

Using a positional cloning strategy, we have identified the EDS5 gene. EDS5 complemented the eds5-3 mutation, as shown by the high SA accumulation and PR-1 expression in pathogen-inoculated transgenic eds5 plants expressing EDS5 compared with inoculated eds5 mutants (Figure 3). Thus, the epistasy of EDS5 to SA accumulation and PR-1 expression was reconfirmed. The expression of EDS5 in eds5 also reduced the high levels of camalexin observed in the eds5 mutant (Nawrath and Métraux, 1999) (Figure 3). This reduction might be attributable to reduced growth of the bacteria in the transgenic eds5 plants complemented with the wild-type EDS5 gene.

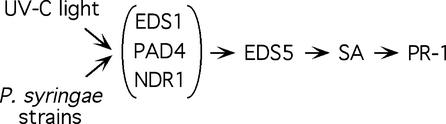

The transcription of EDS5 is induced rapidly by pathogens and abiotic stresses, such as UV-C light, which induce accumulation of SA. The time course of EDS5 expression is similar to that of PAD4 (Jirage et al., 1999), EDS1 (Falk et al., 1999), and NDR1 (Century et al., 1997). However, we showed that the transcript accumulation of EDS5 after exposure to UV-C light and certain pathogens depends on PAD4, EDS1, and NDR1. The onset of expression of EDS5 after exposure to UV-C light was 2 hr earlier than the onset of the increase in SA. Similarly, EDS5 transcript appeared as early as 2 hr after inoculation with P. syringae carrying the avrRpt2 gene, whereas SA started to accumulate 3 to 4 hr after inoculation (D. Lieberherr and J.-P. Métraux, unpublished data). These kinetics suggest that the accumulation of the EDS5 transcript might be involved functionally in the accumulation of SA and plant defense after both UV-C light exposure and pathogen induction. The expression data are summarized in the following model. After either UV-C light exposure or pathogen inoculation, the increase in the transcription of EDS5 depends on functional EDS1, PAD4, and NDR1 genes. This increase in EDS5 transcription is strongly correlated to a subsequent increase in SA and PR-1 transcript accumulation in a timely, coordinated manner (Figure 8). The overall speed of these events, however, depends strongly on the type of signal. Whether the same hierarchy of regulation is found at the protein level will have to be investigated in the future.

Figure 8.

Model for the Transcriptional Regulation of EDS5.

Treatment with UV-C light or inoculation with different strains of P. syringae induce the transcript accumulation of EDS5 when EDS1, PAD4, and NDR1 are functional. An increase in EDS5 expression is followed by the accumulation of SA and PR-1 expression. The gene names shown in parenthesis have different strengths of impact on EDS5 transcription depending on the inducer; their order of action has not been determined.

EDS5 expression also was induced by relatively high concentrations of exogenous SA. The effect of SA was slower than that of UV-C light (onset of expression 6 and 2 hr after treatment, respectively). Interestingly, the transcript accumulation of EDS5 occurred only transiently during the first hours after induction by UV-C light and pathogens and returned close to basal levels after 48 hr, despite high endogenous concentrations of SA (Figures 5 and 6). In addition, EDS5 transcript accumulation was normal in the sid2 mutant, which accumulated low amounts of SA after induction. Therefore, the biological relevance of the SA-mediated expression of EDS5 is not obvious. At optimal concentrations, it might regulate the extent of transient EDS5 expression by a positive feedback loop.

EDS5 encodes a protein of 543 amino acids with a predicted structure that includes nine to 11 membrane-spanning domains and a coiled coil at the N terminus. Its protein structure and its sequence homology with MATE proteins provide evidence that EDS5 might be a transporter. Of the 56 proteins that have been classified as MATE proteins in the Arabidopsis Membrane Protein Library database, none had a biological function assigned until very recently. The mutant transparent testa 12 blocked in flavonoid biosynthesis has been shown to be defective in a MATE pro-tein potentially acting as a vacuolar flavonoid transporter (Debeaujon et al., 2001). Furthermore, AFL5 is a recently identified MATE transporter that renders Arabidopsis resistant to toxins (Diener et al., 2001). Thus, MATE proteins are involved in the transport of different kinds of organic molecules in plants.

The nature of the substances transported by EDS5 remains unknown. NORM, the only biochemically characterized member of the MATE proteins, is a Na+-driven antimicrobial efflux pump (Morita et al., 2000). It is possible that EDS5 transports organic molecules against Na+. These organic molecules could be part of the signal transduction cascade, possibly products of EDS1 and PAD4. It also may be possible that EDS5 has evolved to transport phenolic compounds that are precursors for the biosynthesis of SA.

Interestingly, only six of the 56 MATE proteins of Arabidopsis have an extended hydrophilic region of ∼100 amino acids at the N-terminal end. The MATE proteins of yeast also have this feature. It is possible that the transport activity is regulated by factors binding to this hydrophilic domain, possibly forming a coiled coil in EDS5.

Among the different classes of MATE proteins, EDS5 is most closely related to DINF proteins. In E. coli, DINF is induced after exposure to DNA-damaging agents, including UV-C light, an interesting parallel to EDS5. DinF is part of an operon comprising genes involved in the save our souls (SOS) response (Kenyon and Walker, 1980), a mechanism leading to DNA damage tolerance in prokaryotes (Little and Mount, 1982; Walker, 1995). The genes belonging to this operon are involved in recombination and DNA repair (Walker, 1995). DINF has been found in Gram-negative bacteria, Gram-positive bacteria, and archaebacteria (Bouyoub et al., 1995). Such conservation during evolution suggests that DINF proteins fulfill an important physiological role. In Streptococcus pneumoniae, DinF belongs to an operon induced by competence, also a process requiring DNA recombination events. It is hypothesized that DINF might function in increasing genetic exchanges that allow a better adaptation to environmental conditions (Mortier-Barrière et al., 1998), but the potential transport function of DINF has not been characterized further and it is not known if DINF is involved directly in processes requiring DNA recombination. Because eds5 mutants have not been found to be more sensitive to UV-C light irradiation (data not shown), it remains to be seen if EDS5 is involved in decreasing DNA damage in plants.

Plants have evolved to use functions for building the defense network against pathogens that have parallels in all kingdoms of organisms: R genes and the transcriptional coactivator NPR1 share similarities in mammalian innate immunity, and defensins are found in the defense system of lower vertebrates. This study shows that plants also have recruited proteins for pathogen defense that have structural homologs in prokaryotes, Archea, and lower eukaryotes. It will be interesting to discover the specific functions of EDS5 in the network of defense against pathogens in plants and to determine if functional parallels exist in other organisms.

METHODS

Plants and Growth Conditions of Plants and Bacteria

Arabidopsis thaliana plants, accessions Columbia (Col) and Landsberg erecta (Ler), were used in these experiments. The isolation of the mutant alleles eds5-1 and eds5-2 was as described by Rogers and Ausubel (1997) and Volko et al. (1998), respectively. The isolation of eds5-3 (sid1) and the allelism tests to eds5-1 and eds5-2 were reported by Nawrath and Métraux (1999). sid2 was described by Nawrath and Métraux (1999). Other mutants/plants were obtained from the following persons/institutions: pad4-1, ndr1-1, and npr1-1 from J. Glazebrook (Torrey Mesa Research Institute, San Diego, CA), A. Shapiro (University of Delaware, Newark), and X. Dong (Duke University, Durham, NC), respectively; etr-1 and jar-1 from the Arabidopsis Biological Resources Center (Columbus, OH); NahG plants from J. Ryals (Paradigm Genetics, Research Triangle Park, NC); and eds1-2 and Ler from Jane Parker (Sainsbury Laboratory, John Innes Centre, Norwich, UK). All mutants mentioned above are in the Col background, except eds1, which is in the Ler background. Pseudomonas syringae DC3000 pv tomato and the isogenic strains carrying the avrRpt2 or avrRps4 gene were used for pathogen inoculations. Plants and P. syringae were grown as described by Nawrath and Métraux (1999). Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 MP90 was used for the transformation of Arabidopsis.

Isolation of RNA and DNA

For RNA gel blot analysis, RNA was isolated as described previously (Nawrath and Métraux, 1999). For reverse transcriptase–mediated polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), RNA was isolated from plants 24 hr after inoculation with P. syringae as described by Nawrath and Métraux (1999), except that the RNA was treated with DNase in the presence of the RNase inhibitor rRNAsin (Promega) for 1 hr at 37°C and purified by phenol/chloroform followed by ethanol precipitation. Genomic DNA used for mapping was prepared by fast isolation methods for PCR (Edwards et al., 1991; Klimyuk et al., 1993).

Inoculation with Bacteria and Treatments with UV Light and Salicylic Acid

For RNA gel blot analysis, 4- to 5-week-old plants were syringe inoculated with a suspension of 2 × 106/mL P. syringae DC3000 pv tomato or of the isogenic strains carrying the avrRpt2 or avrRps4 gene. Two- to 3-week-old plants were exposed to UV-C light (254 nm) at 30 cm for 20 min in the dark and then placed in continuous light until harvest. Two- to 3-week-old plants were treated with salicylic acid (SA) either by adding Na-SA to the soil at a final concentration of 0.2 mM or by spraying a 0.01% Silwet L-77 solution (OSi Specialties, Inc., Meyrin, Switzerland) containing Na-SA at 1.0 or 3.3 mM on the shoots. As controls for the second type of treatment, plants were sprayed with 0.01% Silwet L-77 alone.

Mapping, Isolation, and Identification of the EDS5 Gene

EDS5 was mapped to the lower arm of chromosome 4 near the simple sequence length polymorphism (SSLP) marker nga1107 (Nawrath and Métraux, 1999). Genetic fine mapping of the EDS5 gene was performed using additional SSLP and cleaved amplified polymorphic sequence markers (published at http://www.arabidopsis.org). Additional markers were generated by analysis of sequenced bacterial artificial chromosomes (BACs) for simple sequence islands and tested for SSLPs between the Arabidopsis accessions Col and Ler. A total of 1060 randomly selected F2 plants from the cross Ler × eds5-3 were screened with the flanking markers F20D10-45.8 and F23K16-28.4. The marker F20D10-45.8 was amplified using the oligonucleotides 5′-GTTTGTTCCCAATGCGAAAG-3′ and 5′-TTC-GTATGTTACAAGCAAAATC-3′, resulting in 186- and 175-bp fragments in Col and Ler, respectively, whereas the marker F23K16-28.4 was amplified using oligonucleotides 5′-CGCATTTTGTAATCG-TTTCAT-3′ and 5′-AGGTTATCATGCGTGTATTTA-3′, resulting in 205- and 220-bp fragments in Col and Ler, respectively. The genotype of the F2 plants having a recombination in this interval was determined in the F3 population after selfing by measurements of total SA 3 days after inoculation with P. syringae carrying the avrRpt2 gene. The EDS5 gene was determined to be flanked by the SSLP markers at position 49.4 and 79.3 kb of BAC F19H22. The marker F19H22-49.4 was amplified using the oligonucleotides 5′-TCCTATTATGACAAAATTGGT-3′ and 5′-CACTGATTA-TCTCCTTAAGA-3′, giving fragments of 226 bp (Col) and 216 bp (Ler), whereas the marker F19H22-79.3 was amplified using the oligonucleotides 5′-AATACATGTCAAGATCTAAT-3′ and 5′-AAA-ATACACGACTAGGGTTC-3′, giving fragments of 236 bp (Col) and 240 bp (Ler).

A genomic sequence was amplified from BAC F19H22 with the ExpandR High Fidelity PCR Amplification System (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany) using the oligonucleotides 5′-GGAATT-CAGAAGGATTTCTCAAT-3′ and 5′-GGAATTCAACGGTCTGAA-AGAGGA-3′, located 970 and 830 bp upstream from the ATG, respectively, and the oligonucleotide 5′-CCGAATTCTCCTTTG-CTGGGAAG-3′, located 200 bp downstream of the stop codon. These primers introduced EcoRI sites that were used to clone the 4.6- and 4.4-kb PCR fragments into the binary vector pPZP112 (Hajdukiewicz et al., 1994). The eds5-3 mutant was transformed by the floral dip transformation method (Desfeux et al., 2000).

Characterization of the EDS5 cDNA

RT-PCR was performed with the Access RT-PCR system from Promega. The 5′ end of the cDNA was determined by RT-PCR using primers located 100, 150, 220, and 320 bp upstream from the predicted ATG on the annotated genomic sequence. The 3′ end of the cDNA was determined by RT-PCR using primers located 140, 380, 660, and 780 bp downstream of the stop codon of the annotated genomic sequence. The cDNAs of wild-type and mutant alleles were sequenced directly as RT-PCR products. The sequence data were analyzed using the BLAST program against the genomic DNA. The following programs and databases contributed information to the presented work: for functional analyses, SMART (Simple Modular Architecture Research Tool; www.smart.embl-heidelberg); for sequence alignments, Clustal W (decypher2.stanford.edu/algo-cw/clustalW_ax) and T-coffee (www.ch.embnet.org/software/Tcoffee); for protein structure, PRED-TMR (www.O2.db.oua.gr/PRED-TMR), TMHMM (www.cbs.dtn), HMMTOP (www.enzim.hn/hmmtop), and AMPL (Arabidopsis Membrane Protein Library; www.cbs.umn.edu/Arabidopsis).

RNA Gel Blot Analyses

RNA gel blot analyses were performed as described previously (Nawrath and Métraux, 1999). A 500-bp fragment comprising the first exon of the EDS5 gene was taken as a specific probe for EDS5.

Accession Number

The GenBank accession number for the full-length EDS5 cDNA described in this article is AF416569.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate discussions with Mary-Lou Guerinot regarding MATE proteins. We thank Thierry Genoud, Yves Poirier, Liliane Sticher, and Antony Buchala for critical reading of the manuscript and helpful discussions, John Ryals for the kind gift of Arabidopsis NahG seed, Jane Glazebrook for Arabidopsis pad4-1 seed, Allan Shapiro for the Arabidopsis ndr1-1 seed, and Jane Parker for the eds1-2 seed. This work was supported by Grant No. 3100-055662.98 from the Swiss National Foundation to J.-P.M.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1105/tpc.010376.

References

- Aarts, N., Metz, M., Holub, E., Staskawicz, B.J., Daniels, M.J., and Parker, J.E. (1998). Different requirements for EDS1 and NDR1 by disease resistance genes define at least two R gene-mediated signaling pathways in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 10306–10311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouyoub, A., Barbier, G., Quellerou, J., and Forterre, P. (1995). A putative SOS repair gene (dinf-like) in a hyperthermophilic archaeon. Gene 167, 147–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, M.H., Paulsen, I.T., and Skurray, R.A. (1999). The multidrug efflux protein NorM is a prototype of a new family of transporters. Mol. Microbiol. 31, 394–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, R.K. (2000). Salicylic acid and its role in plant defense responses: What do we really know? Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 56, 91–93. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, H., Bowling, S.A., Gordon, A.S., and Dong, X. (1994). Characterisation of an Arabidopsis mutant that is nonresponsive to inducers of systemic acquired resistance. Plant Cell 6, 1573–1584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao, H., Glazebrook, J., Clarke, J.D., Volko, S., and Dong, X. (1997). The Arabidopsis NPR1 gene that controls systemic acquired resistance encodes a novel protein containing ankyrin repeats. Cell 88, 57–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Century, K.S., Holub, E.B., and Staskawicz, B.J. (1995). NDR1, a locus of Arabidopsis thaliana that is required for disease resistance to both bacterial and fungal pathogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92, 6597–6601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Century, K.S., Shapiro, A.D., Repetti, P.P., Dahlbeck, D., Holub, E., and Staskawicz, B.J. (1997). NDR1, a pathogen-induced component required for Arabidopsis disease resistance. Science 278, 1963–1965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debeaujon, I., Peeters, A.J.M., Léon-Kloosterziel, K.M., and Koornneef, M. (2001). The TRANSPARENT TESTA 12 gene of Arabidopsis encodes a multidrug secondary transporter-like protein required for flavonoid sequestration in vacuoles of the seed coat endothelium. Plant Cell 13, 853–871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaney, T.P., Uknes, S., Vernooij, B., Friedrich, L., Weymann, K., Negretto, D., Gaffney, T., Gut-Rella, M., Kessmann, H., Ward, E., and Ryals, J. (1994). A central role of salicylic acid in plant resistance. Science 266, 1247–1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaney, T.P., Friedrich, L., and Ryals, J.A. (1995). Arabidopsis signal transduction mutant defective in chemically and biologically induced disease resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92, 6602–6606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desfeux, C., Clough, S.J., and Bent, A.F. (2000). Female reproductive tissues are the primary target of Agrobacterium-mediated transformation by the Arabidopsis floral-dip method. Plant Physiol. 123, 895–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewdney, J., Reuber, T., Wildermuth, M.C., Devoto, A., Cui, J., Stutius, L.M., Drummond, E.P., and Ausubel, F.M. (2000). Three unique mutants of Arabidopsis identify eds loci required for limiting growth of a biotrophic fungal pathogen. Plant J. 24, 205–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener, A.C., Gaxiola, R.A., and Fink, G.R. (2001). Arabidopsis ALF5, a multidrug efflux transporter gene family member, confers resistance to toxins. Plant Cell 13, 1625–1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, K., Johnstone, C., and Thompson, C. (1991). A simple and rapid method for the preparation of plant genomic DNA for PCR analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 19, 1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk, A., Feys, B.J., Frost, L.N., Jones, D.G., Daniels, M.J., and Parker, J. (1999). EDS1, an essential component of R-gene mediated disease resistance in Arabidopsis, has homology to eukaryotic lipases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 3292–3297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feys, B.J., and Parker, J.E. (2000). Interplay of signaling pathways in plant disease resistance. Trends Genet. 16, 449–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glazebrook, J. (1999). Genes controlling expression of defense responses in Arabidopsis. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2, 280–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glazebrook, J., Rogers, E.E., and Ausubel, F.M. (1996). Isolation of Arabidopsis mutants with enhanced disease susceptibility by direct screening. Genetics 143, 973–982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glazebrook, J., Zook, M., Mert, F., Kagen, I., Rogers, E.E., Crute, I.R., Holub, E.B., Hammerschmidt, R., and Ausubel, F. (1997). Phytoalexin-deficient mutants of Arabidopsis reveal that PAD4 encodes a regulatory factor and that four PAD genes contribute to downy mildew resistance. Genetics 146, 381–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajdukiewicz, P., Svab, Z., and Maliga, P. (1994). The small, versatile pPZP family of Agrobacterium binary vectors for plant transformation. Plant Mol. Biol. 25, 989–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hentze, M.W., and Kulozik, A.E. (1999). A perfect message: RNA surveillance and nonsense-mediated decay. Cell 96, 307–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jirage, D., Tootle, T.L., Reubener, T., Frost, L.N., Feys, B.J., Parker, J.E., Ausubel, F.M., and Glazebrook, J. (1999). Arabidopsis thaliana PAD4 encodes a lipase-like gene that is important for salicylic acid signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 13583–13588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon, C.J., and Walker, G.C. (1980). DNA-damaging agents stimulate gene expression at specific loci in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 77, 2819–2823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinkema, M., Fan, W., and Dong, X. (2000). Nuclear localization of NPR1 is required for activation of PR gene expression. Plant Cell 12, 2339–2350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimyuk, V.I., Caroll, B.J., Thomas, C.M., and Jones, D.G. (1993). Alkali-treatment for rapid preparation of plant material for reliable PCR analysis. Plant J. 3, 493–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little, J.W., and Mount, D.W. (1982). The SOS regulatory system of Escherichia coli. Cell 29, 11–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita, Y., Kodama, S., Shiota, S., Mine, T., Kataoka, A., Mizushima, T., and Tsuchiya, T. (1998). NorM, a putative multidrug efflux protein, of Vibrio parahaemolyticus and its homolog in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42, 1778–1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita, Y., Kataoka, A., Shiota, S., Mizushima, T., and Tsuchiya, T. (2000). NorM of Vibrio parahaemolyticus is an Na+-driven multidrug efflux pump. J. Bacteriol. 182, 6694–6697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortier-Barrière, I., de Saizieu, A., Claverys, J.-P., and Martin, B. (1998). Competence-specific induction of RecA is required for full recombination proficiency during transformation of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol. Miocrobiol. 27, 143–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawrath, C., and Métraux, J.-P. (1999). Salicylic acid induction-deficient mutants of Arabidopsis express PR-2 and PR-5 and accumulate high levels of camalexin after pathogen inoculation. Plant Cell 11, 1393–1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker, J.E., Holub, E.B., Frost, L.N., Falk, A., Gunn, N.D., and Daniels, M.J. (1996). Characterization of eds1, a mutation in Arabidopsis suppressing disease resistance to Peronospora parasitica specified by several different RPP genes. Plant Cell 8, 2033–2046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquier, C., Promponas, V.J., Palaios, G.A., Hamodrakas, J.S., and Hamodrankas, S.J. (1999). A novel method for predicting transmembrane segments in proteins based on a statistical analysis of the SwissProt database: The PRED-TMR algorithm. Protein Eng. 12, 381–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, E.E., and Ausubel, F.M. (1997). Arabidopsis enhanced disease susceptibility mutants exhibit enhanced susceptibility to several bacterial pathogens and alterations in PR-1 gene expression. Plant Cell 9, 305–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryals, J., Uknes, S., and Ward, E. (1994). Systemic acquired resistance. Plant Physiol. 104, 1109–1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryals, J., Weymann, K., Lawton, K., Friedrich, L., Ellis, D., Steiner, H.-Y., Johnson, J., Delaney, T.P., Jesse, T., Vos, P., and Uknes, S. (1997). The Arabidopsis NIM1 protein shows homology to the mammalian transcription factor inhibitor I-B. Plant Cell 88, 57–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah, J., Tsui, F., and Klessig, D.F. (1997). Characterization of a salicylic acid–insensitive mutant (sai1) of Arabidopsis thaliana, identified in a selective screen utilizing the SA-inducible expression of the tms2 gene. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 10, 69–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiomi, N., Fukuda, H., Fukuda, Y., Murata, K., and Kimura, A. (1991). Nucleotide sequence and characterization of a gene conferring resistance to ethionine in yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Ferment. Bioeng. 71, 211–215. [Google Scholar]

- Sticher, L., Mauch-Mani, B., and Métraux, J.-P. (1997). Systemic acquired resistance. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 35, 235–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volko, S.M., Boller, T., and Ausubel, F.M. (1998). Isolation of new Arabidopsis mutants with enhanced disease susceptibility to Pseudomonas syringae by direct screening. Genetics 149, 537–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker, G.C. (1995). SOS responses and DNA damage tolerance in prokaryotes. In DNA Repair and Mutagenesis, E.C. Friedberg, G.C. Walker, and S. Siede, eds (Washington, DC: American Society of Microbiology Press), pp. 407–464.

- Yalpani, N., Enyedi, A.J., Léon, J., and Raskin, I. (1994). Ultraviolet light and ozone stimulate accumulation of salicylic acid, pathogenesis-related proteins and virus resistance in tobacco. Planta 193, 372–376. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y., Fan, W., Kinkema, M., Li, X., and Dong, X. (1999). Interaction of NPR1 with basic leucine zipper protein transcription factors that bind sequences required for salicylic acid induction of the PR-1 gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 6523–6528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J., and Last, R.L. (1996). Coordinate regulation of the tryptophan biosynthetic pathway and indolic phytoalexin accumulation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 8, 2235–2244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.-M., Trifa, Y., Silva, H., Pontier, D., Lam, E., Shah, J., and Klessig, D.F. (2000). NPR1 interacts specifically with members of the TGA/OBF family of transcription factors that bind an element of the PR-1 gene required for induction by salicylic acid. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 13, 191–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, N., Tootle, T.L., Tsui, F., Klessig, D.F., and Glazebrook, J. (1998). PAD4 functions upstream from salicylic acid to control defense responses in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 10, 1021–1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]