Abstract

Background

Arabidopsis thaliana is now the model organism for genetic and molecular plant studies, but growing conditions may still impair the significance and reproducibility of the experimental strategies developed. Besides the use of phytotronic cabinets, controlling plant nutrition may be critical and could be achieved in hydroponics. The availability of such a system would also greatly facilitate studies dealing with root development. However, because of its small size and rosette growth habit, Arabidopsis is hardly grown in standard hydroponic devices and the systems described in the last years are still difficult to transpose at a large scale. Our aim was to design and optimize an up-scalable device that would be adaptable to any experimental conditions.

Results

An hydroponic system was designed for Arabidopsis, which is based on two units: a seed-holder and a 1-L tank with its cover. The original agar-containing seed-holder allows the plants to grow from sowing to seed set, without transplanting step and with minimal waste. The optimum nitrate supply was determined for vegetative growth, and the flowering response to photoperiod and vernalization was characterized to show the feasibility and reproducibility of experiments extending over the whole life cycle. How this equipment allowed to overcome experimental problems is illustrated by the analysis of developmental effects of nitrate reductase deficiency in nia1nia2 mutants.

Conclusion

The hydroponic device described in this paper allows to drive small and large scale cultures of homogeneously growing Arabidopsis plants. Its major advantages are its flexibility, easy handling, fast maintenance and low cost. It should be suitable for many experimental purposes.

Background

Despite its worldwide acknowledged advantages for genetic and molecular studies, Arabidopsis is still hardly amenable to physiological analyses. Its small size and its rosette growth habit somehow make manipulation of the plants ex vitro difficult. Among specific experiments, studies dealing with mineral nutrients and root development would be greatly facilitated by growing the plants on liquid medium. Several hydroponic systems have already been designed for Arabidopsis. While Koyama et al. [1] set up a system which use is limited to young seedlings, others systems allow the completion of the life cycle [2-5]. In most cases, seeds are sown on rockwool or sponge pieces (called hereafter 'seed-holders') soaked with the nutrient solution. As a consequence of their flooding, seeds germinate poorly and must be sown in large excess. Another disadvantage of these seed-holders is that the root system is partly inaccessible for observation or harvest. More technical problems arise if the hydroponic device has to be connected to air for oxygenation of the roots, and/or sterilized to prevent algae contamination. Because of their complexity, these systems were all used on a reduced scale while most physiological analyses – or mutant screens – require large populations of synchronously growing individuals. Synchronization not only means homogeneous growth, but also requires the control of the developmental phases of the plants. We therefore designed a large-scale hydroponic system that allows to control the transition to flowering. Arabidopsis is a facultative long-day (LD-) and vernalization-requiring plant, which means that 'autonomous' flowering may occur in any growth conditions but will be accelerated by environment-dependent 'promotion' pathways [6-8]. We previously showed that the photoperiodic control may be strengthened to such an extent that Arabidopsis becomes responsive to a one-cycle inductive treatment [9]. This consists in growing vernalized plants in 8-h short days (SDs) under low light intensity (LL). On soil, 8-week old plants are then induced to flower by a single 22-h LD while SD-controls remain vegetative for about 3.5 months from sowing.

In this paper, we aimed to establish a simple, inexpensive, and low maintenance hydroponic system for growing Arabidopsis plants. This method is convenient for several purposes since: (i) plant growth can be optimized and synchronized; (ii) mineral nutrition can be easily monitored and manipulated; (iii) roots can be observed and harvested without damage; (iv) floral transition can be induced by a single or multiple inductive cycles.

Results and Discussion

Description of the hydroponic system

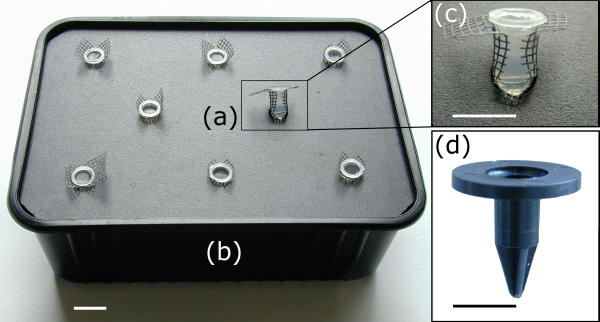

The basic experimental device is formed of two units (Fig. 1): (a) the seed-holders on which individual seeds are germinated and that support the plant throughout the culture; (b) the liquid medium container on which the seed-holders fit straight from sowing.

Figure 1.

Hydroponic device for growing Arabidopsis thaliana plants. Material for growing plants includes (a) a seed-holder and (b) a liquid medium container. (c) Closer view of the seed-holder and of the mesh stuck at its bottom. (d) A machined one-piece seed-holder made of black PVC. Bar = 10 mm.

The seed-holders are small plastic cylinders filled with 0.65 % agar (Fig. 1a). The liquid medium containers are 1-L black plastic boxes covered with a pierced black-PVC plate (Fig. 1b). When the culture is set up, the bottom of the seed holders dip into the nutrient solution. Originally, the seed-holders were inserted into the holes of the container's cover together with a piece of mesh at their bottom to prevent agar coming out (Fig. 1c), and the results presented here were obtained with this system. Since this step was the most time-consuming, we recently designed one-piece seed-holders industrially produced by mould-injection of black plastic (Fig. 1d). They consist in a cylinder with a collar at the top. Two crosswise extensions at the bottom of the cylinder guide the roots and partially obstruct the seed-holder, so retaining the agar.

This hydroponic system is adapted to Arabidopsis growth habit, is simple, cheap, and requires low maintenance. As compared to other devices described in the literature [2,4,5], one of its specific advantages is the nature of the support used for germination and seedling growth. The 0.65 % agar that was used to fill the seed-holders ensures full success for germination and so avoids a 'pre-culture' step and a waste of plant material. Furthermore, agar is a soft support that allows fast growth of the seedling roots, as well as their complete and easy harvest. Seedling root growth through the agar usually took 7 to 10 days, irrespective of the growing conditions.

Another novelty of our system is the movable seed-holder that allows transfer of individual plants from one container to another and makes the system highly flexible. The covers may also be swapped for transfer of plant batches.

Since both the solution container and the cover are made of black plastic, algae growth is prevented; the solution remains clear and no sterilization is required. We also observed that aeration of the nutrient solution was not necessary in small tanks, as reported previously by Arteca & Arteca [5].

All together, these technical advantages make this system up-gradable to any scale. A 1-L container allows to grow 6 to 15 plants; we routinely used 8 plants per unit (Fig. 2). Plant density and growth conditions obviously determine how often the tanks must be refilled. By measuring ion content by ICP-MS and checking pH and conductivity, we found that renewal of the solution was not necessary within the first 4–5 weeks (results not shown) and thereafter depended on growth conditions. The timing of the renewal of the solution will then be specified below for each experiment shown.

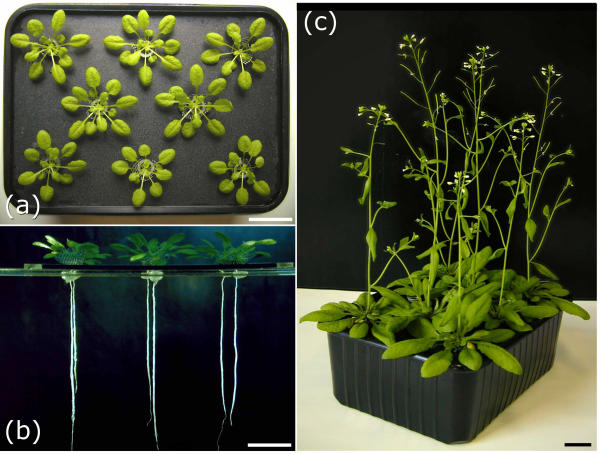

Figure 2.

Six-week old plants of Arabidopsis grown on the standard nutrient solution. Plants of Arabidopsis grown on the standard nutrient solution (see Table 1) in 8-h SDs (a & b), or in 16-h LDs (c), at a photon flux density of 50 μmol.m-2.s-1. Bar = 30 mm.

This experimental device has been set up in the general context of studying the regulation of flowering time in Arabidopsis. The need to synchronize plant development to focus physiological investigations implies a strict control of growing conditions. The quality of the substrate, so the mineral nutrition, was one of the aspects that turned out to be critical to discriminate flowering time and growth rate. Thus, after having designed the equipment, the next step was to make sure that growth was not limited by nutrients in our hydroponic system, and to analyse the floral behaviour. Because of its major role as mineral element, we optimised the N-supply.

Effects of N-supply on plant growth in 8-h SDs

The composition of the nutrient solution was based on Hoagland's, with macronutrients diluted 4-fold [4]. Plant growth response to N-supply was recorded on 5-week old plants grown on a range of N-concentrations, from 220 μM to 21 mM NO3-. The NO3-:NH4+ ratio was kept constant at 27:1 and the nutrient solution was renewed weekly from the third week of growth.

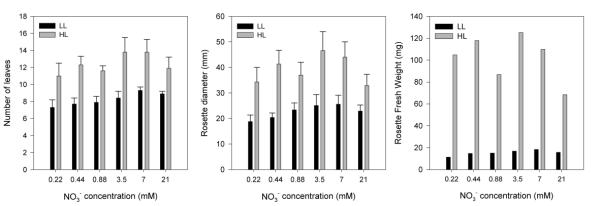

As shown in Figs 3a and 3b, the maximal leaf number and rosette diameter were observed on 3.5 – 7 mM NO3-. These parameters were not strongly affected by N-supply though, since the largest differences between minimum and maximum values in leaf production and rosette growth did not exceed 3 leaves and 12 mm, respectively. However, the rosette or shoot biomass production responded more sharply to changes in N-supply (Fig. 3c). Under high light of 120 μmol.m-2.s-1 (HL), the shoot biomass production was maximum (120 mg) on 3.5 mM NO3- and halved at the highest N-supply. Under low light of 50 μmol.m-2.s-1 (LL), the highest shoot biomass was observed on 7 mM NO3-. On this concentration, 5-week old plants had an average shoot biomass of 20 mg and an average root biomass of 3.8 mg.

Figure 3.

Effect of N-supply on the growth of Arabidopsis. Effect of N-supply on Arabidopsis leaf number (a), rosette diameter (b) and rosette fresh weight (c). Plants were grown in hydroponics for 5 weeks in 8-h SDs at the photon flux density of 50 (LL) or 120 (HL) μmol.m-2.s-1. Results are shown as a function of NO3- supply; NH4+ was provided at a constant NO3-:NH4+ ratio of 27:1. For (a) and (b), results are the mean ± s.d. of two independent experiments; 10 plants per batch. Data for (c) were averaged from 10 pooled plants.

Since further experiments will involve growing the plants in LL for several weeks, the optimum of 7 mM NO3- was selected and the corresponding nutrient solution will be referred to as 'standard' (Table 1). In these conditions, plants were healthy, with deep green leaves and white roots (see Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Chemical composition of the Hoagland and our Arabidopsis 'standard' nutrient solutions

| Chemical component | Hoagland solution (mol.l-1) | Standard solution (mol.l-1) |

| Ca(NO3)2.4H2O | 4.03 10-3 | 1.01 10-3 |

| NH4H2PO4 | 5.22 10-4 | 1.30 10-4 |

| KNO3 | 6.04 10-3 | 5.10 10-3 |

| MgSO4.7H2O | 1.99 10-3 | 4.98 10-4 |

| NaOH | 1.25 10-4 | 3.13 10-5 |

| EDTA | 8.92 10-5 | 2.23 10-5 |

| FeSO4.7H2O | 8.96 10-5 | 2.24 10-5 |

| H3BO3 | 9.68 10-6 | 9.68 10-6 |

| MnCl2.4H2O | 2.03 10-6 | 2.03 10-6 |

| ZnSO4.7H2O | 3.14 10-7 | 3.14 10-7 |

| CuSO4.5H2O | 2.10 10-7 | 2.10 10-7 |

| MoO3 | 1.39 10-7 | 1.39 10-7 |

| Co(NO3)2.6H2O | 8.59 10-8 | 8.59 10-8 |

| NH4NO3 | 0 | 2.93 10-5 |

Flowering analyses

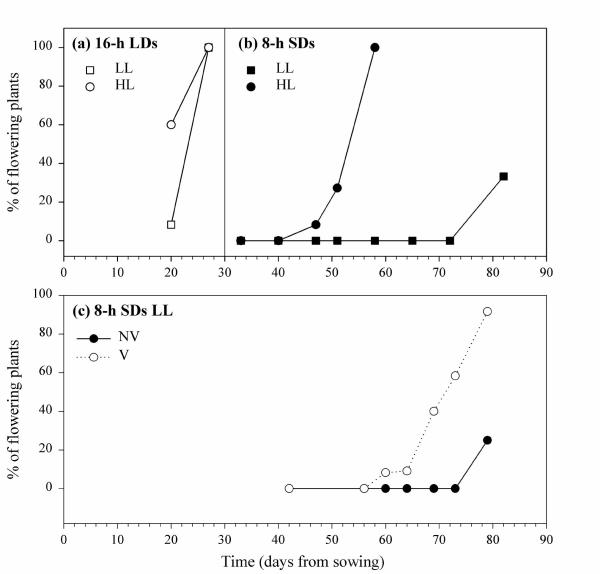

Autonomous flowering was analysed for non-vernalized plants, in 8-h SDs, under both HL and LL (Fig. 4b). For these experiments, the nutrient solution was changed after five weeks and, at the same time, the plant population was thinned out by selecting 6 plants per 1 L-container.

Figure 4.

Effect of daylength and photon flux density on the flowering response of Arabidopsis plants. Non-vernalized plants were grown in hydroponics with the standard nutrient solution in 8-h SDs (b) or 16-h LDs (a) at the photon flux density of 50 (LL) or 120 (HL) μmol.m-2.s-1. (c) Comparison between non-vernalized (NV) and vernalized (V) plants grown in 8-h SDs / LL (vernalization: 2°C, 6 weeks). Twelve to 16 plants were dissected at each time.

Under HL, the floral transition started after 6 weeks and all plants had formed visible floral buds 8 weeks after sowing. LL strongly delayed the process since the floral buds were visible in the earliest individuals after about 10 weeks. This delay was partly rescued by vernalization (2°C, 6 weeks) that advanced the floral transition by about 10 days (Fig. 4c). Note that all plants eventually formed flowers, even when non-vernalized.

Expectedly, flowering was much faster in 16-h LDs than in 8-h SDs (see Fig. 2): all plants had formed floral buds after 4 weeks (Fig. 4a), under both HL and LL. The entire life cycle was analysed under HL: non-vernalized plants reached anthesis about one month after the initiation of floral buds – i.e. two months after sowing – and produced an average of 473 ± 45 mg of seeds (2864 ± 555 seeds) per plant. In total, the generation time was about 2.5 months.

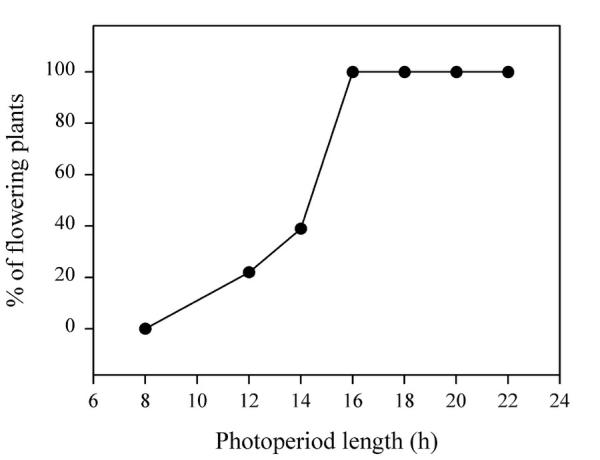

In order to induce synchronous flowering, non-vernalized plants grown in 8-h SDs / LL were exposed to a single 22-h LD after 5, 6, 7, or 8 weeks (see Material and Methods). It was found that the single LD allowed full floral induction from the age of 6 weeks (data not shown). With 7-week old plants, we observed in two independent experiments that the critical photoperiod was about 12 h, and that lengthening the photoperiod to 16 h was actually sufficient to trigger flowering in the whole population (Fig. 5). These results are in close agreement with our previous description of the synchronous systems for inducing flowering in Arabidopsis, on soil [9]. However, a clear advantage of our hydroponic system is that plants grow faster: synchronous induction can be achieved with 6- or 7-week old non-vernalized plants, while the floral induction of 8-week old plants by a single LD was obtained on soil, only if the seeds had been previously vernalized for several weeks. Thus hydroponics not only allows to shorten the length of the experiments, but also to separate the photoperiod- and vernalization-promotion pathways in the 'one-shot' system. The above results show that our hydroponic system fulfils the experimental need of synchronising plant growth (Fig. 3) and development (Fig. 4). To illustrate a more specific application of hydroponics – that is to manipulate mineral nutrition -, we will summarize here our observations on Arabidopsis plants impaired in N-assimilation.

Figure 5.

Effect of the duration of a single LD on the flowering response of 7-week old non-vernalized Arabidopsis plants grown in hydroponics. Plants were previously grown in 8-SDs at a photon flux density of 50 μmol.m-2.s-1; the flowering response was evaluated by dissection of 12 to 16 plants 18 days after the LD treatment.

Flowering of nitrate reductase deficient mutants

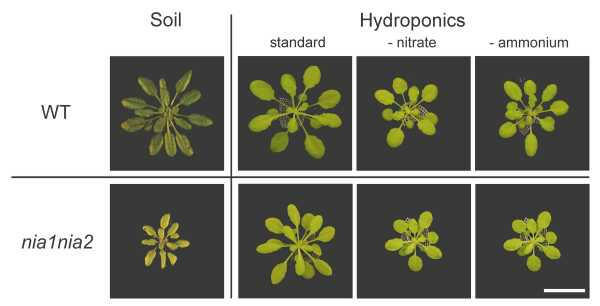

The nia1nia2 double mutant contains a mutation in each of the two nitrate reductase structural genes (NIA) and has a residual activity of 0.5% [10]. Our interest in studying this genotype was to analyze whether nitrate – which accumulates in the mutants that are unable to reduce it – has any effect on flowering time. We observed that nia1nia2 plants grew poorly on soil and were chlorotic (Fig. 6), independently of the photoperiod and light intensity (data not shown). Flowering was also delayed, even more when the photoperiod was short: nia1nia2 plants never flowered in 8-h SDs, initiated about 10 more leaves than WT in 16-h LDs, and behaved almost as WT in continuous light (Table 2).

Figure 6.

Arabidopsis WT and nia1nia2 double mutant grown in 8-h SDs on soil or in hydroponics. On soil, plants were grown under 120 μmol.m-2.s-1 for 10 weeks. In hydroponics, plants were grown under 50 μmol.m-2.s-1 for 6 (WT) and 8 weeks (nia1nia2), on the 'standard' or ammonium-free solution. Bar = 20 mm.

Table 2.

Effect of daylength on total leaf number initiated before the first flower by vernalized WT and nia1nia2 plants. Plants were grown under a photon flux density of 120 μmol.m-2.s-1, on soil. Results of a typical experiment are given; standard deviation calculated on 12 plants

| Photoperiod | ||||

| Line | 8 h | 12 h | 16 h | 24 h |

| WT | 71.8 ± 3.4 | 26.3 ± 3.3 | 13.0 ± 1.6 | 13.3 ± 1.5 |

| nia1nia2 | indefinite | 43.9 ± 4.0 | 23.3 ± 3.7 | 17.5 ± 3.1 |

The flowering response to a single 22-h LD of vernalized plants grown on soil was also strongly reduced: whereas full induction was obtained with 8-week old WT plants, only 13% of 10-week old nia1nia2 plants responded to the LD (Table 3). Although we used older mutant plants in an attempt to compensate for their slower growth rate, their size was still reduced as compared to WT when exposed to the LD, which might explain their lower sensitivity. It was thus impossible to answer the question whether the flowering phenotype of the mutants was specifically linked to nitrate accumulation or a side-effect. In other experiments, we tried to restore normal growth by watering the mutants weekly with 10 mM ammonium sulfate or 10 mM ammonium nitrate, but did not observe any significant improvement (data not shown). In contrast, the nia1nia2 double mutants could be induced to flower by a single LD when grown in our hydroponic system, with the 'standard' nutrient solution (changed once after 5 weeks). Plants still did not grow as fast as WT (Fig. 6), though, but the difference was reduced as compared to our measurements on soil: after 7 weeks in SDs / LL, the nia1nia2 double mutant had a rosette diameter of 52 ± 6 mm and 21 ± 2 leaves while the WT reached a rosette diameter of 77 ± 6 mm and had 27 ± 2 leaves. When this difference in growth rate was balanced by inducing mutant plants later than WT, i.e. at a similar size (rosette diameter about 60 mm) rather than at the same age, a full floral response to a single LD was almost restored: vernalized nia1nia2 plants were fully induced by a single 22-h LD after 8 weeks of growth in SDs / LL, as compared to 6 weeks for WT (Table 3). Since growth could never be made up on soil, the results presented in this paper show the significant progress our hydroponic system would allow in this field. Since nia1nia2 plants are much impaired in nitrate reduction, their healthy growth in hydroponics was probably due to ammonium availability. We indeed observed that the double mutants grown on an ammonium-free solution exhibited a reduced growth, accumulated anthocyanins and were unable to respond to the LD, while WT plants hardly showed any effect (Fig. 6). These experiments allowed us to conclude that flowering depends on the ability of the plant to use the available form of nitrogen, and that nitrate by its own does not play a significant role in this process since plants accumulating nitrate flower almost as well as WT.

Table 3.

Flowering response of vernalized WT and nia1nia2 plants submitted to one 22-h LD. Plants were grown in 8-h SDs / 50 μmol.m-2.s-1, then subjected to the LD treatment or not (SD-controls). On soil, WT and nia1nia2 plants were exposed to the LD when 8- and 10-week old, respectively. In hydroponics, plants were 6- and 8-week old, respectively.

| % of flowering plants | ||||

| Soil | Hydroponics | |||

| Lines | SD | LD | SD | LD |

| WT | 0 | 100 | 0 | 100 |

| nia1nia2 | 0 | 13 | 0 | 92 |

Conclusions

In conclusion, this paper describes an original device for growing Arabidopsis hydroponically. Beside the general advantages of this culture system, such as control of mineral nutrition and access to the root system, we specifically paid attention to technical parameters ensuring homogeneity of the plant material, i.e. successful germination, synchronised growth and development. Containers and seed-holders were also designed for flexibility, easy setting up and low maintenance of the culture, so that this equipment will be suitable for many experimental purposes.

Methods

Set up of the culture

Seed holders were prepared by cutting off the cap and the conical end of 0.5 ml microfuge tubes (VWR International, Overijse, Belgium). Melted 0.65% agar was poured into the cylinders placed upside down on paper tape. Once cooled down, the seed-holders may be wrapped with plastic and stored at 4°C until used. The containers were black Polarcup boxes (18 × 13 × 6.5 cm, L × W × H; VariaPack, Leuven, Belgium) covered with a black PVC plate pierced of 9-mm diameter holes. Before sowing, 1 L of nutrient solution was placed in each container and the seed-holders were set up. To prevent leaching of agar in the nutrient solution, the bottom of the seed-holders was wrapped with a piece (15 × 40 mm) of grey mesh (1 mm) (Fig. 1c) that stuck to it when both parts were inserted together into the holes of the container cover. For sowing, seeds were suspended in 0.2 % agar and dropped individually with a pipette on the top of the agar-filled seed-holders.

Plant material and growing conditions

After stratification of the seeds at 2°C for 5 days or vernalization at 2°C for 6 weeks on wet filter paper and in darkness, plants of Arabidopsis (Columbia) were grown in 8-h SDs or 16-h LDs. The photon flux density was 120 (HL) or 50 μmol.m-2.s-1 (LL) PAR (Very High Output fluorescent tubes; Sylvania, Zaventem, Belgium) and the temperature was 20°C. Relative humidity – which is critical for the success of germination and seedling establishment – was set optimally at 70%.

Flowering response

Flowering time was recorded in 8-h SDs and 16-h LDs by regular observation of the plants under the dissecting microscope. A plant was recorded as 'floral' when at least one floral bud was visible at the apex, and a '% of flowering plants' was calculated for each batch examined.

For the analysis of the flowering response to the single cycle treatments, plants were grown for 5, 6, 7, or 8 weeks in 8-h SDs under LL before being exposed to a single 22-h LD, as described previously [9]. The floral response to one LD was more deeply investigated for 7-week old plants which were exposed to a single LD of different durations. This allowed to establish the 'induction curve' and so determine the minimal duration of the inductive LD or 'critical photoperiod' [11]. In these experiments aiming at synchronous induction of flowering, the floral response was evaluated 18 days after the photoperiodic treatment, by dissecting the plants under the dissecting microscope and evaluating the '% of flowering plants' as explained above.

List of abbreviations

HL: high light

ICP-MS: inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry

LD: long day

LL: low light

SD: short day

WT: wild type

Authors' contributions

PT designed the seed-holder, participated in the setting up of the system and carried out the growth analyses. LC participated in the setting up of the system and performed nitrate reductase mutant and flowering time experiments. AH was involved in plant culture monitoring. AP participated in the setting up of the system and was involved with EK in maintaining the growing device. GB was the promoter of the research programs which funded this work. CP was co-promoter of the programs funded by the E.C. and the University of Liège, surpervised the study and drafted the manuscript.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

L.C. is grateful to the F.N.R.S. and P.T. to the F.R.I.A. for the award of research fellowships. This research was supported by grants from the European Community Contract BI04 CT97-2231; the Interuniversity Poles of Attraction Programme (Belgian State, Prime Minister's Office – Federal Office for Scientific, Technical and Cultural Affairs; P4/15); the 'Action de Recherches Concertées' 98/03-219 and the University of Liège (Fonds Spéciaux). We thank Dr. S. Melzer for critical reading of the manuscript. We wish to thank A. Schmitz and D. Libion for taking care of the plants.

Contributor Information

Pierre Tocquin, Email: pierre.tocquin@ulg.ac.be.

Laurent Corbesier, Email: laurent.corbesier@ulg.ac.be.

Andrée Havelange, Email: andree.havelange@ulg.ac.be.

Alexandra Pieltain, Email: alexandra_pieltain@hotmail.com.

Emile Kurtem, Email: emile.kurtem@ulg.ac.be.

Georges Bernier, Email: gbernier@ulg.ac.be.

Claire Périlleux, Email: cperilleux@ulg.ac.be.

References

- Koyama H, Toda T, Yokota S, Dawair Z, Hara T. Effects of aluminium and pH on root growth and cell viability in Arabidopsis thaliana strain Landsberg in hydroponic culture. Plant Cell Physiol. 1995;36:201–205. [Google Scholar]

- Delhaize E, Randall PJ. Characterization of a phosphate-accumulator mutant of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol. 1995;107:207–213. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.1.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirai MY, Fujiwara T, Chino M, Naito S. Effects of sulfate concentrations on the expression of a soybean seed storage protein gene and its reversibility in transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 1995;36:1331–1339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibeaut DM, Hulett J, Cramer GR, Seemann JR. Maximal biomass of Arabidopsis thaliana using a simple, low-maintenance hydroponic method and favorable environmental conditions. Plant Physiol. 1997;115:317–319. doi: 10.1104/pp.115.2.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arteca RN, Arteca JM. A novel method for growing Arabidopsis thaliana plants hydroponically. Physiol Plant. 2000;108:188–193. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3054.2000.108002188.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koornneef M, Alonso-Blanco C, Peeters AJM, Soppe W. Genetic control of flowering time in Arabidopsis. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1998;49:345–370. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.49.1.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy YY, Dean C. The transition to flowering. Plant Cell. 1998;10:1973–1989. doi: 10.1105/tpc.10.12.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Périlleux C, Bernier G. The control of flowering: do genetical and physiological approaches converge? In: O'Neill SD, Roberts JA, editor. In Plant Reproduction Annual Plant Reviews. Vol. 6. Sheffield Academic Press, Sheffield; 2002. pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Corbesier L, Gadisseur I, Silvestre G, Jacqmard A, Bernier G. Design in Arabidopsis thaliana of a synchronous system of floral induction by one long day. Plant J. 1996;9:947–952. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1996.9060947.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson JQ, Crawford NM. Identification and characterization of a chlorate-resistant mutant of Arabidopsis thaliana with mutations in both nitrate reductase structural genes NIA1 and NIA2. Mol Gen Genet. 1993;239:289–297. doi: 10.1007/BF00281630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang A. Physiology of flower initiation. In: Ruhland W, editor. In Encyclopedia of Plant Physiology. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1965. pp. 1379–1536. [Google Scholar]