Abstract

Background

Putrescine is the intermediate product of arginine decarboxylase pathway in Escherichia coli which can be used as an alternative nitrogen source. Transaminase and dehydrogenase enzymes seem to be implicated in the degradative pathway of putrescine, in which this compound is converted into γ-aminobutyrate. But genes coding for these enzymes have not been identified so far.

Results

The 1.8-kbp DNA fragment containing E. coli K12 ygjG gene with aer-ygjG intergenic region was examined. It was found that the fragment contains σ54-depended open reading frame (ORF) of 1,380 nucleotides encoding a 459-amino acid polypeptide of approximately 49.6 kDa. The cytidine (C) residue localized 10 bp downstream of the σ54 promoter sequence was identified as the first mRNA base. The UUG translation initiation codon is situated 36 nucleotides downstream of the mRNA start. The YgjG was expressed as a his6-tag fused protein and purified to homogeneity. The protein catalyzed putrescine:2-oxoglutaric acid (2-OG) aminotransferase reaction (PATase, EC 2.6.1.29). The Km values for putrescine and 2-OG were found to be 9.2 mM and 19.0 mM, respectively. The recombinant enzyme also was able to transaminate cadaverine and, in lower extent, spermidine, and gave maximum activity at pH 9.0.

Conclusion

Expression of E. coli K12 ygjG coding region revealed σ54-depended ORF which encodes a 459-amino acid protein with putrescine:2-OG aminotransferase activity. The enzyme also was able to transaminate cadaverine and, in lower extent, spermidine.

Background

Polyamines, such as putrescine and spermidine, are present in virtually all living cells, from bacteria to plant and human cells, with a very important though poorly understood biological role [1,2]. They can bind to nucleic acids, stabilize membrane and stimulate activity of several enzymes [2-5]. Despite the proved necessity of intracellular polyamine for optimal cellular growth, polyamine accumulation can lead to inhibition of cellular growth and protein synthesis [6,7]. Two major metabolic routes of polyamines breakdown have been described, one for the free bases via Δ1-pyrroline (4-aminobutyraldehyde) and the other via N-acetyl derivatives. Acetylation pathway serves to prevent polyamine toxicity in prokaryotes and eukaryotes [1,8]. Spermidine and spermine are acetylated and further oxidized by polyamine oxidase or either deacetylated or excreted from the cell. Acetyltransferase forming exclusively of N-acetylspermidine has been described in E. coli [9,10], but neither spermidine-deacetylating activity nor N-acetylspermidine oxidase activity has been detected, suggesting that the N-acetylspermidine is excreted or kept in the inert acetylated form [11]. In the aminotransferase pathway of polyamine degradation, amino groups are converted from polycations to electron acceptors. Polyamine aminotransferase activity was found in some microorganisms [12-14]. In the case of putrescine, the resulting Δ1-pyrroline is an intermediate product of 4-aminobutyric acid (GABA) metabolism [8,15,16]. The putrescine:2-oxoglutarate (2-OG) aminotransferase enzyme (PATase, EC 2.6.1.29) of E. coli was partially purified from the mutant strains [12,17] and characterized. The synthesis of putrescine aminotransferase is controlled by catabolite repression and nitrogen availability [18]. But the corresponding gene remains to be identified. It was speculated that E. coli K12 ygjG gene (b3073, [19]) specifies the ω-aminotransferase which either removes the amino groups from compounds with terminal primary amines, or adds amino groups to compounds with an aldehyde group [20]. Putrescine and compounds metabolized to putrescine activate ygjG expression [21], which suggests a possible role in putrescine catabolism. To elucidate YgjG biochemical functions, we have cloned the ygjG gene, expressed, purified an active recombinant protein and investigated some molecular and biochemical properties of the YgjG enzyme.

Results

Cloning and characterization of the 5'-flanking region of the ygjG gene

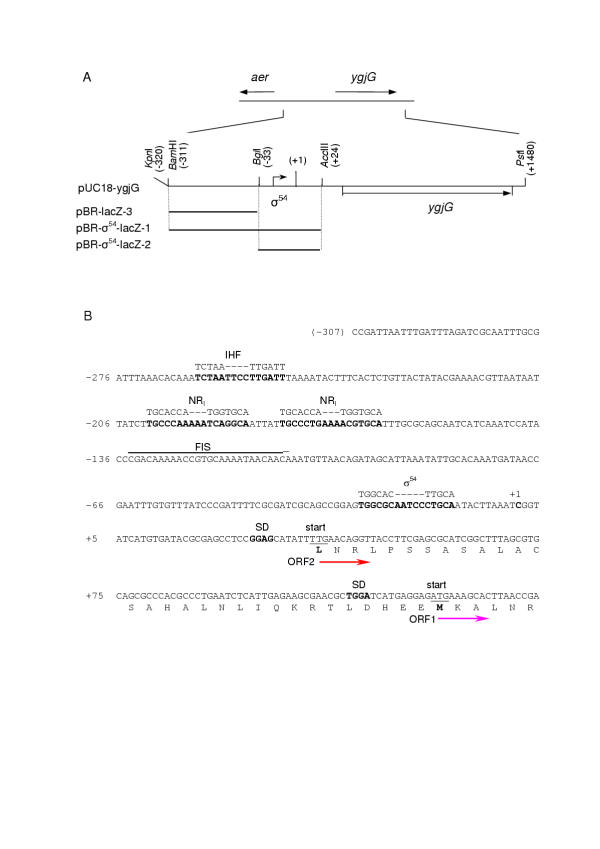

The 1.8-kbp DNA fragment from E. coli K12 genomic DNA including ygjG and aer-ygjG intergenic region (Fig. 1A) was cloned into pUC18 vector and sequenced. The obtained plasmid was designated as pUC18-ygjG. The computer analysis of the ygjG upstream regulatory region revealed recognizable consensus sequence of σ54-dependent promoter with score 70.7 [21]. The localization of this promoter is shown on Fig. 1. Likewise, according to DNA array data, the nitrogen limitation results in 3- to 5-fold increase in levels of ygjG transcripts [22]. For more detail characterization of the role of the 5'-flanking region in the ygjG expression and nitrogen starvation induction we compared the expression levels of three different ygjG upstream regions fused to the lacZ reporter gene in plasmid pBRP [23] under different growth conditions. pBR-σ54-lacZ-1 and pBR-σ54-lacZ-2 plasmids carried 343-bp KpnI-AccIII and 56-bp BglI-AccIII fragments, respectively, containing predicted σ54 promoter sequence, and pBR-lacZ-3 plasmid harbored 282-bp KpnI-BglI fragment upstream of σ54 promoter. E. coli TG1 cells were transformed by each of plasmids and β-galactosidase productions in three media: LB broth and salt M9 media [24] with ammonium or supplemented with proline as a sole nitrogen source were analyzed (Table 1).

Figure 1.

The scheme of the ygjG gene and aer-ygjG intergenic region. A. The fragment (from -311 to +1480) containing ygjG gene (b3073) with aer-ygjG intergenic region, and sites for restriction enzymes used in cloning procedure are shown. The orientation of genes and location of σ54 promoter are represented by arrows. Nucleotides numbering is in relation to ygjG mRNA transcription initiation site designated as +1. ygjG upstream fragments fused with lacZ and subcloned into pBRP [23] vector are shown as bold lines. B. The sequence of ygjG upstream region. Nucleotides numbering as in part A. σ54 promoter, putative NRI and IHF binding sites, SD sequences and the first mRNA base are bold. The consensus sequences for IHF, NRI and σ54 promoter are shown above the main sequence. Two possible translation start codons are underlined and corresponding N-terminal amino acids are bold. The putative FIS binding site http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov:80/ is overlined. The directions of ORF1 and ORF2 translation are shown by arrows.

Table 1.

Expression of the lacZ fusions under different growth conditions

| β-Galactosidase activity, MUb | |||

| Plasmida | LBc | M9, Nitrogen Sufficientc | M9, Nitrogen Limitedc |

| pBR-σ54-lacZ-1 | 190 | 3,500 | 22,500 |

| pBR-σ54-lacZ-2 | 140 | 400 | 800 |

| pBR-lacZ-3 | 110 | 130 | 170 |

a Plasmids were transformed into E. coli TG1 strain. b In Miller units [24]. c For growth conditions and β-galactosidase assay see Materials and Methods.

The all three recombinant strains were found to have low β-galactosidase activity (below 200 Miller unites [24]) in LB broth. The strain harboring pBR-lacZ-3 also revealed low levels of expression in all media, pointing that the 282-bp fragment doesn't include noticeable promoter sequence. The strain carried plasmid pBR-σ54-lacZ-2 containing practically σ54 sequence alone, showed 3 – 5 times higher lacZ expression levels than pBR-lacZ-3 in both variant of minimal media. But lacZ activity was dramatically increased in the strain harboring pBR-σ54-lacZ-1, especially under nitrogen limited conditions. The increase was about 9-fold in M9 medium with ammonium and 28-fold in M9 with proline in comparison with pBR-σ54-lacZ-2. Thus, the 56-bp region contains promoter sequence, and we concluded that σ54 promoter localized in the BglI-AccIII fragment is the main promoter of ygjG. The KpnI-BglI fragment is strongly essential for ygjG expression in minimal media and activation of ygjG expression (up to 6-fold) under nitrogen limitation. Because enhancer proteins are absolutely necessary for σ54-dependent transcription [25] we reanalyzed the sequence of this fragment and found some putative binding sites for E. coli activators: two general nitrogen regulatory protein (NRI) binding sites and binding site for integration host factor (IHF) (Fig. 1B). In addition, existence of factor of inversion stimulation (FIS) binding site was suggested http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov:80/. Thus the activation of ygjG expression is complicated, depends on growth conditions and needs further investigations.

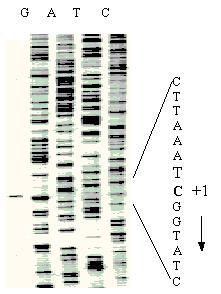

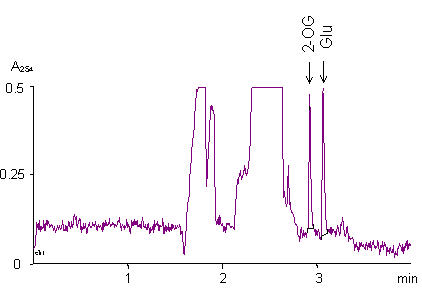

TG1 cells harboring pUC18-ygjG were grown in three media (see above), the total RNAs were isolated and used to identify the transcriptional initiation site of ygjG mRNA by primer extension experiment. The same cDNA fragment was observed as the major transcript for all three RNA preparations, and the cytidine (C) was identified as the first mRNA base (Fig. 2, also shown as "+1" in Fig. 1). The quantities of ygjG cDNA synthesized were estimated using Typhoon imager. The highest level of transcript was observed for RNA preparation from cells grown under nitrogen limitation, while only about 20% and less than 1% of it were detected if cells were grown in M9 and LB media, accordingly. Also, crude protein extracts from these cells were examined for PATase activity with putrescine as amino group donor and with 2-OG as acceptor. Enzyme activity was determined routinely by glutamate formation, which was measured by capillary zone electrophoresis (CE) (Fig. 3). The second product of the reaction, γ-aminobutyraldehyde, was unstable [16] and formed cycled Δ1-pyrroline at alkaline pH. PATase activity was highest in extracts of cells grown under nitrogen limitation (47 nmol·min-1·mg-1). It was significantly reduced in cell extracts from M9 medium (nearly proportionally to decreasing of ygjG transcript level), and was practically undetectable in cell extracts from LB medium (near to the limit of accuracy for the CE method). Thus, the level of ygjG transcription and PATase activity correlated in cells grown in each of three media used.

Figure 2.

Determination of the ygjG transcriptional initiation site. Transcriptional initiation site was determined by primer extension. The reaction was carried out as described in Materials and Methods and cDNA transcript of RNA preparation obtained from cells grown under nitrogen limited conditions was analyzed on 6% PAGE (left track). The corresponding sequencing ladders are also labeled. The first nucleotide of ygjG mRNA (C) is bold and shown as "+1". The direction of transcription is shown by the arrow.

Figure 3.

Assay of PATase activity by capillary zone electrophoresis. Capillary zone electrophoresis of PATase reaction mixture. For assay conditions see Materials and Methods. Picks of 2-OG and glutamate are shown by arrows.

The predicted AUG initiation codon for the ygjG gene of 1290 bp (denoted downstream as ORF1) which codes 429-amino acid polypeptide (SWISS-PROT Database, P42588) is situated 126 nucleotides downstream of the mRNA start. Analysis of the nucleotide sequence revealed the other ORF (denoted as ORF2) encoding 459-amino acid protein with UUG initiation codon (Fig. 1B), which is 30 amino acids upstream from an in frame ORF1 start codon. Because both putative ORFs have the potential Shine-Dalgarno (SD) sequence [26], we decided to express each of them as his6-tag fused recombinant protein to determine if these recombinant constructs actually yield a catalytically active enzyme.

Cloning and expression of the ORF1 and OFR2 coding proteins

The 1.29-kbp (ORF1) and 1.38-kbp (ORF2) DNA fragments of pUC18-ygjG were cloned in translation fusion with N-terminal his6-tag sequence under the control of the T7 promoter in pET15b(+) vector. The resulting plasmids, pET-Ht-ORF1 and pET-Ht-ORF2, were expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) cells. SDS-PAGE of cellular extracts demonstrated a high level of expression of these proteins. To elucidate which of polypeptides encodes an active enzyme, crude extracts were examined for PATase activity. The essential level of glutamate formation activity was observed in crude cell extracts of the BL21(DE3) harboring pET-Ht-ORF2. It was equal to 2.16 μmol·min-1·mg-1. The BL21(DE3)(pET-Ht-ORF1) strain exhibited only traces of PATase activity. The BL21(DE3) strain transformed with pET15b(+) as a control revealed no activity. Obviously, the UUG is the real initiation codon of the ygjG encoding 459-amino acid protein with a calculated molecular mass (Mr) of 49,644 Da.

Purification and characterization of the ygjG gene recombinant product

In order to confirm the identity of ORF2 as the gene encoding PATase, we purified recombinant protein from the BL21(DE3)(pET-Ht-ORF2) strain by immobilized-metal-affinity chromatography (IMAC) to give a final preparation having a specific activity of 11.68 μmol·min-1·mg-1 with yield of 81%. The purity of Ht-YgjG recombinant protein was about 95%. SDS-PAGE showed one distinctive band with a relative Mr of about 52 kDa. This value well corresponds to the sum of mass of 49.6 kDa for ORF2 coding protein and 2.1 kDa for his6-tag leader peptide.

Some parameters of PATase reaction were determined. The enzyme was active at the alkaline pH, with the maximum activity at pH 9.0 in Tris-HCl buffer and displayed a broad temperature optimum between 20°C and 80°C with maximum activity at 60°C. The Km values for putrescine and 2-OG were determined to be 9.2 mM and 19.0 mM, respectively.

Substrate specificity of purified Ht-YgjG was measured with different donors and acceptors of amino group (Table 2). Several compounds (putrescine, cadaverine, spermidine, agmatine, and ornithine) were tested for their ability to function as amino donors for 2-OG. Among them putrescine was found to be the best amino group donor for the aminotransferase activity of Ht-YgjG. Slightly lower activity with cadaverine (97%) and significantly lower with spermidine (32%) was detected. Also, three keto acids: 2-OG, α-ketobutyrate and pyruvate were used as amino acceptors for putrescine. The enzyme did exhibit significant activity toward α-ketobutyrate (38%) and, to less extent, pyruvate (12%) with putrescine. Almost no activity was detected with ornithine as amino acceptor, while ornithine aminotransferase activity was annotated for ygjG in GeneBank Database. GABA, diaminopimelic acid, acetylornithine were completely inactive as amino group donors.

Table 2.

Substrate specificity of purified recombinant Ht-YgjG

| Substrate | Relative activity (%)a |

| Amino group donorb | |

| Putrescine | 100 |

| Cadaverine | 97 |

| Spermidine | 32 |

| Agmatine | 2 |

| L-Ornithine | 2 |

| Amino group acceptorb | |

| 2-OG | 100 |

| α-ketobutyric acid | 38 |

| Pyruvic acid | 12 |

a The PATase activity with 2-OG as amino group acceptor was arbitrary defined as 100% relative activity. b 2-OG was used as amino acceptor with different polyamines and amino acid as amino group donors, and putrescine was used as amino group donor with different amino acceptors at final concentrations of 10 mM, respectively.

Discussion

In addition to being involved in polyamine breakdown, the reaction catalysed by PATase appears to be the fourth reaction of the arginine decarboxylase pathway of arginine degradation to succinate via putrescine and GABA in E. coli [15,27]. We have found that E. coli K-12 ygjG gene (denoted above as ORF2) encodes for enzyme catalyzing PATase reaction. According to published data [21,22] and our experimental data, ygjG expression is under the control of the σ54 promoter and is induced at minimal salt medium and under nitrogen starvation. Two putative NRI binding sites and IHF binding site in ygjG upstream region proposed to be involved into transcription regulation. The cytidine localized 10 bp downstream from the σ54 promoter sequence was identified as the first mRNA base. The potential SD site (GGAG) is located 6 nucleotides upstream from the UUG initiation codon of ygjG and this distance is functional for E. coli genes [28]. The UUG is initiation codon for about 3% of E. coli proteins [19] but it is less effective at promoting translation [29] than is AUG codon. Thus the initiation of translation from UUG codon could be a way to confine the synthesis of the YgjG protein.

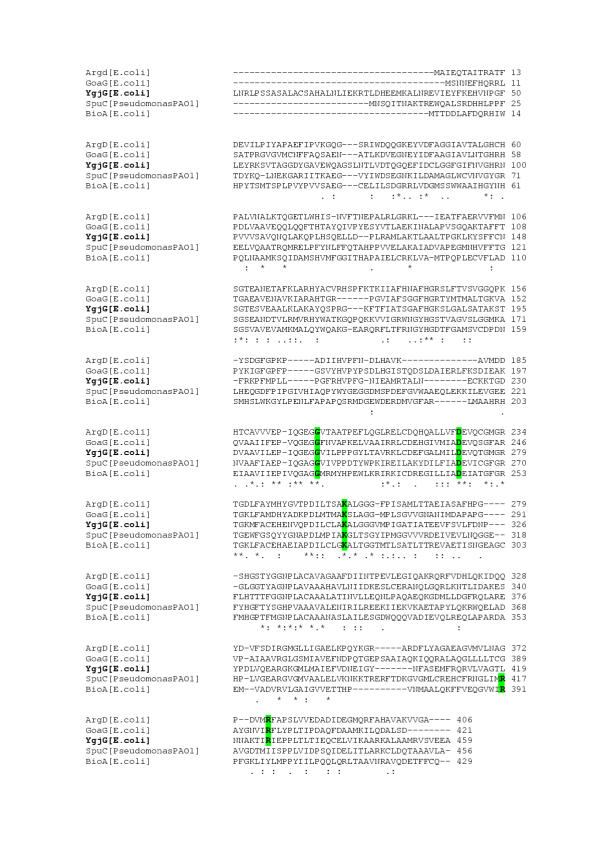

BLAST [30] analysis of the translated ygjG sequence revealed moderate identity to the aminotransferases belonging to the class III of pyridoxal phosphate (PLP) dependent aminotransferase family, which includes E. coli acetylornithine delta-aminotransferase (36% identity), GABA aminotransferase (34% identity), 7,8-diaminopelargonic acid synthetase (33% identity). In addition, the significant level of identity, 27%, was found for Pseudomonas aeruginosa SpuC protein catalyzing putrescine:pyruvate aminotransferase reaction [13]. The multiple sequence alignment of these enzymes (Fig. 4) showed that YgjG contains the conserved sequence segments with four invariant amino acid residues (i.e. Gly-245, Asp-271, Lys-300, and Arg-426) known to be involved in binding of either the substrate or the coenzyme PLP [20]. Interestingly, the N-terminal sequence of the YgjG is the longest among them, and we believe that this sequence may be essential for substrate specificity and enzyme activity. YgjG showed the greatest identity (94%) with a probable aminotransferase encoded by STY3396 gene from Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi CT18 (NP 457608) suggesting that STY3396 is likely to be PATase.

Figure 4.

Multiple sequence alignment of YgjG to known class III PLP-dependent aminotransferases. The alignment was performed with ClustalW http://www.ebi.ac.uk/clustalw The residues that are identical in all the displayed sequences are marked by asterisks, conserved residues are marked by dots and the four invariant residues (G, D, K and R) proposed for aminotransferases are bold and boxed. Abbreviations are: ArgD, acetylornithine delta-aminotransferase (ATase) (AAC76384); GoaG, 4-aminobutyric acid ATase (AAC74384); SpuC, putrescine:pyruvate ATase [13]; BioA, 7,8-diaminopelargonic acid synthetase (AAC73861).

We have purified Ht-YgjG recombinant protein and found that pH optimum and substrate specificity of the enzyme, except for GABA, was in a good accordance with data of Kim [12] obtained for partially purified PATase enzyme from mutant E. coli strain, while the Km value for 2-OG of Ht-YgjG is higher. The Km values of enzymes belonging to the class III aminotransferases are significantly different, from micromolar to millimolar levels, for different substrates (see, for example, http://www.brenda.uni-koeln.de). As mentioned above, the N-terminal sequence of YgjG may be essential for substrate specificity and enzyme activity. According to our preliminary data, Km values for putrescine and 2-OG of unfused YgjG enzyme are 3–4 times lower than those for the fused Ht-YgjG protein (data not shown). Thus, the N-end modification of YgjG by his6-tag leader fusion alters kinetic constants of the native enzyme. Therefore further investigations are needed to more detail characterization of YgjG protein.

Conclusions

We found that E. coli K12 ygjG σ54-depended ORF encodes the 459-amino acid protein. The recombinant enzyme, purified as a fuse with his6-tag leader, possessed the putrescine:2-OG aminotransferase activity. The enzyme also was able to transaminate cadaverine, spermidine and utilized α-ketobutyrate and pyruvate as amino acceptors.

Methods

Bacterial strains and plasmids

E. coli strains TG1(K12 supE hsdΔ5 thi Δ (lac-proAB) F'[traD36 proAB+ lacIqlacZΔM15]) and BL21(DE3)(B F- dcm ompT hsdS(rB- mB-) gal λ (DE3)) were used as a recipients, MG1655 (K12 λ-, F-) [31] was used for gene amplification. Plasmids pUC18 (Fermentas), pBRP [23] and pET15b(+) (Novagen) were used as a vectors for cloning.

Construction of the recombinant plasmids

The E. coli K12 ygjG gene with upstream aer-ygjG intergenic region was amplified from MG1655 genomic DNA using two oligonucleotides 5'-TTGGATCCGATTAATTTGATTTAGATCGCA-3' and 5'-TTCTGCAGCCTGCGGGCGTACGCGTCG-3' as primers. The 1,8 kb PCR product was digested by BamHI and PstI and cloned into pUC18 vector, yielding pUC18-ygjG plasmid. The insertion in pUC18-ygjG was sequenced for frame verification.

The 338-bp KpnI-AccI, 56-bp BglI-AccIII and 282-bp KpnI-BglI fragments were excised from pUC18-ygjG, fused with lacZ reporter gene and cloned into pBRP vector (pBR322-based plasmid containing pUC18 polylinker region), yielding pBR-σ54-lacZ-1, pBR-σ54-lacZ-2 and pBR-lacZ-3 plasmids, respectively.

The ygjG ORF1 and ORF2 sequences were amplified by PCR from pUC18-ygjG using phosphorilated downstream primers 5'-CCGATATCATGAAAGCACTTAACCGAGAG-3' and 5'-CCGATATCTTGAACAGGTTACCTTCGAG-3', respectively, designed so as to provide translation fusion between his6-tag leader sequence and the gene of interest, and upstream primer 5'-TTCTGCAGCCTGCGGGCGTACGCGTCG-3'. PCR products were cloned into blunted vector pET15b(+)/NdeI-BamHI to construct plasmids pET-Ht-ORF1 and pET-Ht-ORF2, respectively, and insertions were sequenced.

Growth, induction conditions and preparation of cell-free extracts

Strains were routinely grown in LB broth or M9 medium [24]. Nitrogen limited conditions were provided using M9 medium lacking ammonium and supplemented with 2 mM of a proline as nitrogen source. All media contained 100 μg/ml ampiciline. Strains were grown aerobically at 37°C.

For expression of lacZ fusions, E. coli TG1 harboring pBR-σ54-lacZ-1, pBR-σ54-lacZ-2 or pBR-lacZ-3 plasmids were grown overnight in M9 medium, washed by 15 mM NaCl, diluted to optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.07 by LB, M9 or M9 nitrogen limited medium. The resulting cultures were grown until reaching on OD600 of about 3.0 (stationary phase).

The synthesis of his6-tag fused recombinant proteins was induced in BL21(DE3) harboring pET-Ht-ORF1 or pET-Ht-ORF2 plasmid. When the cell density in LB medium had reached OD600 of 1.0, 1 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside was added followed by 2 h incubation.

For preparation of cell-free extracts bacteria were harvested by centrifugation and washed twice with TE buffer. The cell pellets were stored frozen for several days at -70°C without significant loss of enzyme activity. Frozen cells were thawed, suspended to 0,025 g (wet weight) per ml in buffer A (20 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.4, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 10 μM PLP), and disrupted by sonication followed by centrifugation to remove debris.

RNA isolation and primer extension start site analysis

The TG1 harboring pUC18-ygjG has been grown in LB, M9 media and under nitrogen limited conditions, and the total RNAs were isolated using RNAsy MiniKit (Sigma) according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

Oligonucleotide 5'-CGCTTCTCAATGAGATTCAGGGCGTGG-3' which is complementary to the region from +44 to +71 relatively to the ygjG ORF2 initiation codon was radiolabeled by T4 polynucleotide kinase (Pharmacia) with γ-[33P]ATP (6000 Ci/mmol).

Aliquots of mRNA (5 μg) were denaturated at 65°C for 10 min, incubated in reaction buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.3, 75 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 20 mM DTT) containing 0.5 ng of the labeled oligonucleotide, rTth reverse transcriptase (5 u) (Perkin Elmer) and 1 mM deoxyribonucleotide triphosphates at 37°C for 1 h. The synthesized cDNAs were denaturated at 65°C for 10 min and analyzed by electrophoresis on 6% acrylamide gel. The same primer was used for the DNA sequence ladder run on the same gel. The quantities of synthesized cDNAs were estimated using Typhoon 9210 imager and ImageQuant version 5.2 software (Amersham, Molecular Dynamics).

Purification of Ht-YgjG

The Ht-YgjG was purified from 150 ml of BL21(DE3)(pET-Ht-ORF2) induced culture. Frozen cells (60 mg) were thawed, suspended in 75 ml of buffer B (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 1 mM PMSF) and disrupted by sonication followed by centrifugation to remove debris (10 000 g, 20 min, 4°C). The imidazol and NaCl were added to supernatant up to final concentrations of 50 mM and 500 mM, respectively. The supernatant was applied to a His-Trap column (1 ml) (Pharmacia) equilibrated with the same buffer. The protein was eluted with 10 ml of buffer C (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 400 mM imidazol, 500 mM NaCl). The Ht-YgjG containing fractions were applied on Sephadex G-25 column (Pharmacia) equilibrated with buffer D (20 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.4, 15% glycerol, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF, 10 μM PLP) and eluted in the same buffer. The Ht-YgjG containing fractions were combined, aliquoted and stored at -70°C until required.

The protein concentration was estimated following the method described by Bradford with bovine serum albumin as the standard [32]. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE (10%) [33].

Enzyme assays and analytical methods

β-Galactosidase assay was performed in cell-free extracts of TG1 cells harboring pBR-σ54-lacZ-1, pBR-σ54-lacZ-2 and pBR-lacZ-3 plasmids according to Miller [24].

PATase activity was routinely assayed as the formation of L-glutamic acid from putrescine and 2-OG at 37°C. The assay mixture contained (in 0.1 ml of total volume) 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 9.0, 25 μM PLP, 10 mM putrescine, 10 mM 2-OG. The reaction mixture was preincubated at 37°C for 5 min, and the reaction was started by the addition of cell extract or enzyme solution (5 μl). The reaction was stopped by adding 15 μl of HCl (10%). The analysis of glutamic acid formation was carried out using a Quanta 4000E Capillary Electrophoresis System (Waters) with an uncoated fused-silica capillary (75 μm inner diam. × 60 cm) at 25 kV potential. The injection was performed hydrostatically for 25 s. The separation buffer consisted of 50 mM Tris-base, 25 mM benzoic acid, pH 8.5, 0.25 mM tetradecyl-trimethyl-ammonium bromide (for indirect UV detection at 254 nm). The calibration at three concentrations of the L-glutamic acid (0.025 mM, 0.05 mM, 0.1 mM) and three concentrations of the 2-OG (0.05 mM, 0.1 mM, 0.2 mM) was carried out.

The kinetic constants of the Ht-YgjG were evaluated by varying the concentration of putrescine at a 2-OG concentration of 20 mM or by varying the concentration of 2-OG at a putrescine concentration of 15 mM. The enzyme kinetics data were fitted to Michaelis-Menten kinetics and Km values were calculated. The substrate specificity of Ht-YgjG was determined using assay as described above with different polyamines and amino acids as amino group donors and 2-OG as acceptor, or with different acceptors and putrescine as amino group donor.

Authors' contributions

N.N.S. carried out the experimental part of the study and drafted the manuscript. S.V.S. conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination, and performed capillary electrophoresis. I.B.A. carried out the primer extension study. L.R.P. conceived of the study, supervised the work, and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Yuri I Kozlov, Dr. Mikhail M Gusyatiner, Dr. Tatiana A Yampolskaya and Dr. Vladimir M Belkov for useful discussions and thoughtful criticisms of the manuscript and Anna E Novikova for help in providing capillary electrophoresis.

Contributor Information

Natalya N Samsonova, Email: nsams@genetika.ru.

Sergey V Smirnov, Email: servasmir@mtu-net.ru.

Irina B Altman, Email: ialtman@mail.ru.

Leonid R Ptitsyn, Email: ptitsyn@genetika.ru.

References

- Pegg AE. Recent advances in the biochemistry of polyamines in eukaryotes. Biochem J. 1986;234:249–262. doi: 10.1042/bj2340249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabor CW, Tabor H. Polyamines in microorganisms. Microbiol Rev. 1985;49:81–99. doi: 10.1128/mr.49.1.81-99.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abraham KA. Studies on DNA-dependent RNA polymerase from Escherichia coli. 1. The mechanism of polyamine induced stimulation of enzyme activity. Eur J Biochem. 1968;5:143–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1968.tb00348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frydman L, Rossomando PC, Frydman V, Fernandez CO, Frydman B, Samejima K. Interactions between natural polyamines and tRNA: an 15N NMR analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:9186–9190. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.19.9186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S, Panagiotidis CA, Canellakis ES. Transcriptional effects of polyamines on ribosomal proteins and on polyamine-synthesizing enzymes in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:3464–3468. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.9.3464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y, Kashiwagi K, Fukuchi J, Terao K, Shirahata A, Igarashi K. Correlation between the inhibition of cell growth by accumulated polyamines and the decrease of magnesium and ATP. Eur J Biochem. 1993;217:89–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb18222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pegg AE. Polyamine metabolism and its importance in neoplastic growth and a target for chemotherapy. Cancer Res. 1988;48:759–774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Large PJ. Enzymes and pathways of polyamine breakdown in microorganisms. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1992;88:249–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1992.tb04991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuchi J, Kashiwagi K, Takio K, Igarashi K. Propeties and structure of spermidine acetyltransferase in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:22581–22585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui I, Kamei M, Otani S, Morisawa S, Pegg AE. Occurence and induction of spermidine N1-acetyltransferase in Escherichia coli. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1982;106:1155–1160. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(82)91233-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ignatenko NA, Fish JL, Shassetz DP, Woolridge DP, Gerner EW. Expression of the human spermidine/spermine N1-acetyltransferase in spermidine acetylation-deficient Escherichia coli. Biochem J. 1996;319:435–440. doi: 10.1042/bj3190435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KH. Purification and properties of a diamine α-ketoglutarate transaminase from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1964;239:783–786. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu CD, Itoh Y, Nakada Y, Jiang Y. Functional analysis and regulation of the divergent spuABCDEFGH-spuI operons for polyamine uptake and utilization in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:3765–3773. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.14.3765-3773.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yorifuji T, Kondo S, Shimizu E, Naka T, Ishihara T. Purification and characterization of polyamine aminotransferase of Arthrobacter sp. TMP-1. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1997;122:537–543. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snaibe E, Metzer E, Halpern YS. Metabolic pathway for the utilization of L-arginine, L-ornithine, agmathine, and putrescine as nitrogen sources in Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1985;163:933–937. doi: 10.1128/jb.163.3.933-937.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakoby WB, Fredericks J. Pyrrolidine and putrscine metabolism: γ-aminobuyraldehyde dehydrogenase. J Biol Chem. 1959;234:2145–2150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prieto-Santos MI, Martin-Checa J, Balana-Force R, Garrido-Pertierra A. A pathway for putrescine catabolism in Escherichia coli. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1986;880:242–244. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(86)90085-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snaibe E, Metzer E, Halpern YS. Control of utilization of L-arginine, L-ornithine, agmathine, and putrescine as nitrogen sources in Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1985;163:938–942. doi: 10.1128/jb.163.3.938-942.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blattner FR, Plunkett G, III, Bloch CA, Perna NT, Burland V, Riley M, Collado-Vides J, Glasner JD, Rode CK, Mayhew CF, et al. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science. 1997;277:1453–1474. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta PK, Hale TI, Christen P. Aminotransferases: demonstration of homology and division into evolutionary subgroups. Eur J Biochem. 1993;214:549–561. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb17953.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitzer L, Schneider BL. Metabolic context and possible phisiological thermes of σ54-dependent genes in Escherichia coli. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2001;65:422–444. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.65.3.422-444.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer DP, Soupene E, Lee HL, Wendisch VF, Khodursky AB, Peter BJ, Bender RA, Kustu S. Nitrogen regulatory protein C-controlled genes of Escherichia coli: scavenging as a defense against nitrogen limitation. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:14674–14679. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.26.14674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ptitsyn LR, Fatova MA, Stepanov AI. Expression of the bioluminescence system of Photobacterium leiognathi in E. coli. Mol Gen Mikrobiol Virusol Russian. 1990;16:26–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller J. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Cold Spring Harbor Press. 1972.

- Buck M, Gallegos MT, Studholme DJ, Guo Y, Gralla JD. The bacterial enhancer-dependent σ54 (σN) transcription factor. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:4129–4136. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.15.4129-4136.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shine J, Dalgarno L. The 3' terminal sequence of Escherichia coli 16S ribosomal RNA: complementarity to nonsense triplets and ribosome binding sites. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1974;71:1342–1346. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.4.1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shnaider BL, Kiupakis AK, Reitzer LJ. Arginine catabolism and the arginine succinyltransferase pathway in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4278–4286. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.16.4278-4286.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makrides SC. Strategies for achieving high-level expression of genes in Escherichia coli. Microbiol Rev. 1996;60:512–538. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.3.512-538.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy P, Peterkofsky A, McKenney K. Translational efficiency of the Escherichia coli adenylate-cyclase gene – mutating the UUG initiation codon to GUG or AUG resultes in increased gene-expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:54656–5660. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.17.5656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyer MS, Reed RR, Steitz JA, Low KB. Identification of a sex-factor-affinity site in Escherichia coli as gamma delta. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1981;45:135–140. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1981.045.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method of for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature London. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]