Abstract

Sorting nexin (SNX) 1 and SNX2 are mammalian orthologs of Vps5p, a yeast protein that is a subunit of a large multimeric complex, termed the retromer complex, involved in retrograde transport of proteins from endosomes to the trans-Golgi network. We report the cloning and characterization of human orthologs of three additional components of the complex: Vps26p, Vps29p, and Vps35p. The close structural similarity between the yeast and human proteins suggests a similarity in function. We used both yeast two-hybrid assays and expression in mammalian cells to define the binding interactions among these proteins. The data suggest a model in which hVps35 serves as the core of a multimeric complex by binding directly to hVps26, hVps29, and SNX1. Deletional analyses of hVps35 demonstrate that amino acid residues 1–53 and 307–796 of hVps35 bind to the coiled coil-containing domain of SNX1. In contrast, hVps26 binds to amino acid residues 1–172 of hVps35, whereas hVps29 binds to amino acid residues 307–796 of hVps35. Furthermore, hVps35, hVps29, and hVps26 have been found in membrane-associated and cytosolic compartments. Gel filtration chromatography of COS7 cell cytosol showed that both recombinant and endogenous hVps35, hVps29, and hVps26 coelute as a large complex (∼220–440 kDa). In the absence of hVps35, neither hVps26 nor hVps29 is found in the large complex. These data provide the first insights into the binding interactions among subunits of a putative mammalian retromer complex.

INTRODUCTION

The movement of lipid and protein components between intracellular organelles requires the regulated interactions of many molecules (Novick and Zerial, 1997; Bryant and Stevens, 1998). Genetic approaches in yeast have proved invaluable in identifying proteins required for normal trafficking. For example, the efficient delivery of hydrolases to the vacuole requires nearly 50 proteins. Mutations in any of these vacuolar protein sorting (Vps) proteins lead to defects in protein trafficking to the vacuole (Bankaitis et al., 1986; Rothman and Stevens, 1986). Two proteins shown to be essential for proper delivery of the hydrolase carboxypeptidase Y to the vacuole are Vps5p and the carboxypeptidase Y receptor (Vps10p) (Marcusson et al., 1994; Westphal et al., 1996). Vps10p binds carboxypeptidase Y in the trans-Golgi network (TGN), and carries it to prevacuolar endosomes where the hydrolase dissociates. The hydrolase is delivered to the vacuole, whereas Vps10p is recycled to the TGN for additional rounds of transport. This recycling step is a Vps5p-dependent process. Vps5p is also required for retaining enzymes such as dipeptidyl amino peptidase and Kex2p in the late-Golgi by retrieving mislocalized molecules from the prevacuolar endosome (Nothwehr and Hindes, 1997; Seaman et al., 1997, 1998). To carry out its biological functions, Vps5p assembles into a “retromer complex” containing at least four other subunits: Vps17p, Vps26p, Vps29p, and Vps35p (Seaman et al., 1998). Inactivation of the genes for any one of these retromer proteins results in defects in protein recycling from endosomes to the trans-Golgi (Horazdovsky et al., 1997; Seaman et al., 1997; Nothwehr et al., 1999).

Sorting nexins (SNXs) 1 and 2 are the human orthologs of yeast Vps5p (Horazdovsky et al., 1997; Haft et al., 1998). SNX1 was first identified via its ability to bind to the cytoplasmic domain of the epidermal growth factor receptor in a yeast two-hybrid assay (Kurten et al., 1996). Later it was shown that both SNX1 and SNX2 interact with many receptors, including the long form of the leptin receptor and also the receptors for insulin, platelet-derived growth factor, and epidermal growth factor. Furthermore, SNX1 and SNX2 self-associate and associate with one another (Haft et al., 1998; Kurten et al., 1998). Presently, it is unclear whether SNX1 and SNX2 are involved in the trafficking of these receptor molecules.

In this study, we report the cloning of cDNAs encoding human orthologs of three components of the retromer complex (Vps26p, Vps29p, and Vps35p) identified in yeast, and investigate their binding interactions. Because the amino acid sequences of SNX1, hVps26, hVps29, and hVps35 closely resemble their yeast orthologs, we have designated these molecules as human retromer proteins. Our data are consistent with a model in which hVps35 forms the core of a multimeric complex and binds directly to at least three other proteins: hVps26, hVps29, and SNX1. This work provides the first insights into the nature of the molecular interactions that mediate the assembly of the multiple subunits of the complex. The close similarity between the yeast retromer proteins and their human orthologs strongly suggests a conservation of their functions as well.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Lines

COS7 cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified medium supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin.

Antibodies

Anti-c-myc (A-14 and 9E10), anti-calnexin (C-20), anti-cathepsin H (N-18), anti-lysosome-associated membrane protein I (LAMPI) (C-20), and anti-epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor (1005) antibodies were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Anti-HA monoclonal antibody (HA.11) was from Berkeley Antibody (Richmond, CA). Anti-GM130 and anti-early endosomal antigen 1 (EEA1) monoclonal antibodies were obtained from Transduction Laboratories (Lexington, KY). Anti-human Vps26, Vps29, and Vps35 antibodies, as well as anti-SNX1 and anti-SNX2 antibodies were made by immunizing rabbits with fusion proteins containing glutathione S-transferase (GST) and the entire coding region of each molecule. The GST fusion proteins were expressed by using the pGEX-5X-1 vector from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech (Pascataway, NJ) (Haft et al., 1998) and purified by using standard techniques. Rabbits were immunized by Covance Laboratories (Madison, WI) or Zymed Laboratories (San Francisco, CA). Donkey anti-rabbit IgG-peroxidase and sheep anti-mouse IgG-peroxidase were obtained from Amersham Life Science (Arlington Heights, IL), and mouse anti-goat IgG-peroxidase was from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories (West Grove, PA).

Cloning of Human Vps26, Vps29, and Vps35 cDNAs

Using the published amino acid sequence of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Vps29p/PEP11 (GenBank accession number AAF0496), and the yeast and mouse sequences of Vps26p/hβ58/PEP8 (accession numbers 41623 and 4758509) and Vps35p/Mem3 (GenBank accession numbers AF191298 and U47024, respectively), we searched the expressed sequence tag nucleotide sequence database of the National Center for Biotechnology Information for the human orthologs of these proteins. We obtained several I.M.A.G.E. Consortium expressed sequence tag cDNA clones (Lennon et al., 1996) from Research Genetics (Huntsville, AL) or American Tissue Culture Collection. Plasmid DNA was isolated by using reagents supplied by Qiagen (Chatsworth, CA). The clones were sequenced on one or both strands starting with vector-specific primers, followed by a series of sequence-specific primers (available upon request) by using the ABI PRISM dye terminator cycle sequencing kit and an ABI automated sequencer, model 373A (Perkin Elmer-Cetus, Applied Biosystems Division, Foster City, CA). Standard molecular biology techniques were used to construct full-length cDNAs for hVps26, hVps29, and hVps35.

Tissue Distribution of hVps26, hVps29, and hVps35

Multiple-tissue Northern blots containing ∼2 μg of purified human poly(A)+ RNA were obtained from Clontech (Palo Alto, CA). Probes for Northern blot analyses were made by digesting hVps26 cDNA with EcoRI and XhoI, hVps29 cDNA with EcoRV and BglII, and hVps35 with BglI and NcoI. Fragments were gel purified, 32P-labeled by using a random primed DNA labeling kit (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN), diluted in Express Hyb buffer, and hybridized overnight at 68°C. Blots were then washed according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Construction of Epitope-tagged Sorting Nexins and Vps Proteins

Myc epitope tags were introduced at the 5′ end of full-length and mutant constructs of SNX1, SNX2, hVps26, hVps29, and hVps35 proteins by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with the Expand high-fidelity PCR kit (Roche Molecular Biochemicals). Sequences of the primers are available upon request. The epitope-tagged molecules were then cloned into pCDNA(3.1±) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), pCMV5myc-1 (Andersson et al., 1989), or pCIneo expression vectors (Promega, Madison, WI) by using standard cloning techniques.

Coimmunoprecipitation Experiments

COS7 cells (2–3 × 105 cells/well) were plated into six-well dishes 16–20 h before the start of the transfection. Cells were washed twice with serum-free Dulbecco's modified medium and transfected with LipofectAMINE Plus according to the manufacturer's instructions (Life Technologies). Between 28 and 30 h after the start of the transfection the cells were washed in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline and scraped into 0.25 ml of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 0.5% [vol/vol] Triton X-100, 0.3 M NaCl plus protease inhibitor tablet [Roche Molecular Biochemicals]). The cells were then solubilized for 30 min on ice, and insoluble debris removed by centrifugation (14,000 × g for 20 min) at 4°C. The proteins were detected by immunoblotting, or by immunoprecipitation of extract (0.4 ml) followed by immunoblotting as described elsewhere (Levy-Toledano et al., 1993; Haft et al., 1994).

Yeast Strains and Plasmids

S. cerevisiae EGY48 (a-trp, ura3-52,his3, leu2), the pB42AD and pLexA expression vectors were obtained from Clontech. Full-length and mutant constructs of human SNX1, SNX2, and Vps26, Vps29, and Vps35 were made via PCR, ligated into the TOPO TA cloning vector (Invitrogen), and then subcloned into the yeast expression vectors. Growth and maintenance of yeast strains have been carried out as described by Clontech (Gyuris et al., 1993; Zervos et al., 1993). Plasmid transformation of yeast was by the lithium acetate method (Ausubel et al., 1994). The liquid β-galactosidase assay was done according to the manufacturer's instructions. Each construct used was first checked for auto-activation of the β-galactosidase reporter gene. None of the constructs used showed detectable auto-activation of the reporter gene (i.e., in excess of the empty vector alone) during the 30-min assay time used in these studies. At least six independent yeast colonies were assayed for each interaction studied. In addition, many of the interactions studied were repeated by reversing the molecule expressed in the activation domain plasmid with the molecules expressed in the binding domain plasmid. Similar results were found (our unpublished results).

Gel Filtration Chromatography

COS7 cells (0.8–3 × 107) were scraped into 500 μl of ice-cold homogenization buffer (20 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.2, 0.8 M sorbitol, 2 mM EDTA, and Complete protease inhibitor tablets [Roche Molecular Biochemicals]) and lysed by 15 passages through a 25-gauge needle. To obtain cytosolic fractions, lysates were centrifuged at 284,000 × g for 45 min at 4°C in a Sorvall S120AT2 rotor (Sorvall-Heraeus, Newtown, CT). The resulting supernatant (0.5 ml) was loaded onto a Sephacryl S-300 column (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) and equilibrated in homogenization buffer. Fractions (1.25 ml) were collected, the proteins concentrated by precipitation with cold trichloroacetic acid (6% vol/vol final concentration), and washed twice with ice-cold acetone (Dunn and Hubbard, 1984). Aliquots of total lysates, cytosolic and membrane fractions, and precipitated column fractions were then solubilized in Laemmli buffer, run on 7.5% (vol/vol) SDS gels, and the various Vps and SNX proteins were detected by immunoblotting (Haft et al., 1994). Blue dextran 2000 was used to determine the void volume of the column. The following protein standards (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) were used to calibrate the column: thyroglobulin (669 kDa), ferritin (400 kDa), aldolase (158 kDa), and albumin (67 kDa). The sizes of the cytosolic complexes were estimated by comparison to the peaks of the protein standards. The amount of each protein present in the various fractions was determined by using the NIH Image software package.

Subcellular Fractionation of Liver Homogenates

Sedimentation Analysis.

Rat livers were weighed and homogenized in 5 volumes of 0.25 M sucrose solution containing 3 mM imidazole buffer (pH 7.4) plus Complete protease inhibitor tablets (Roche Molecular Biochemicals). Nuclei and unbroken cells were removed by centrifugation at 460 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The resulting supernatant was spun at 145,000 × g for 90 min in a Beckman 60 Ti rotor (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA) to give a supernatant (cytosolic fraction) and a pellet (microsomal fraction). The microsomal pellet was resuspended in 15–20 ml of sucrose imidazole buffer with a Potter-Elvejhem homogenizer, and 5 ml was applied to a 1.06–1.25 g/ml linear sucrose gradient (32 ml). After centrifugation for 12–15 h at 83,000 × g in a SW28 Beckman rotor, 1.2-ml fractions were collected from the top of the gradient by using a Buchler Auto Densi-Flow fractionator (Buchler Instruments, Fort Lee, NJ) (Dunn and Hubbard, 1984). Six hundred microliters of each fraction was then immunoprecipitated with either anti-Vps35 or anti-Vps26 antibody as described above.

Floatation Analysis.

Rat livers were weighed and homogenized in 5 volumes of 0.25 M STKM buffer (0.25 M sucrose, 50 mM Tris, 25 mM KCl, and 5 mM MgCl2 buffer [pH 7.4] plus Complete protease inhibitor tablets [Roche Molecular Biochemicals]). Nuclei and unbroken cells were removed by centrifugation at 460 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The resulting supernatant was adjusted to 1.5 M sucrose in TKM buffer by adding 2 M sucrose in TKM buffer. Dense homogenate (19 ml) was applied to the bottom of each tube and overlaid with an 18-ml linear sucrose gradient (1.5–0.2 M STKM). The gradients were spun for 3.5 h at 83,000 × g in a SW28 Beckman rotor. After centrifugation, 1.0-ml fractions (18 total) were collected from the top of the gradient by using a Buchler Auto Densi-Flow fractionator (Buchler Instruments) (Dunn and Hubbard, 1984). In addition, the load (19 ml) was collected and the material that pelleted was resuspended in 10 ml of 0.25 M STKM buffer by using a dounce homogenizer. Aliquots of each fraction were analyzed by Western blotting for Vps35, Vps26, and various organelle marker proteins.

RESULTS

Cloning and Characterization of human Vps26, Vps29, and Vps35

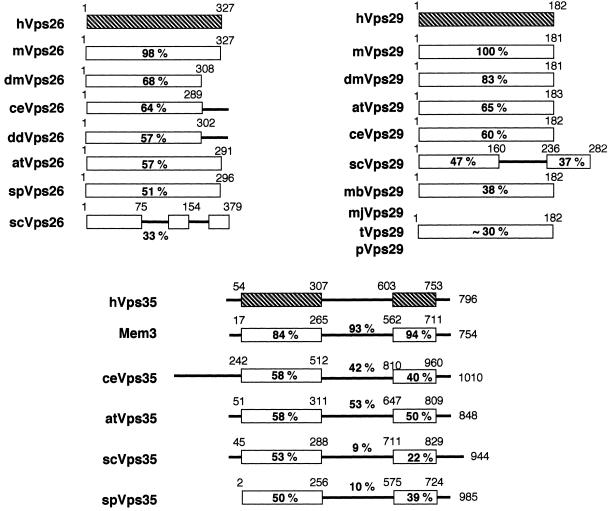

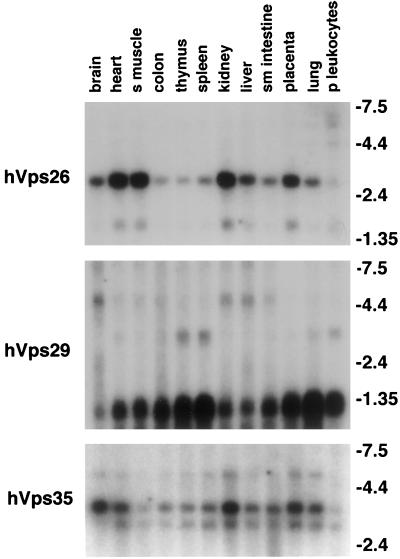

Recently, several yeast proteins (Vps5p, Vps17p, Vps26p, Vps29p, and Vps35p) have been shown to form a complex involved in retrograde trafficking between the prevacuolar endosome and the TGN (Horazdovsky et al., 1997; Seaman et al., 1997, 1998). The retromer complex, as it has been termed, may act as a coat for retrograde vesicles leaving the prevacuolar compartment. We have cloned full-length cDNAs of the human homologs of Vps26p, Vps29p, and Vps35p (Figure 1). Human Vps26, Vps29, and Vps35 are hydrophilic proteins containing 327, 182, and 796 amino acids, respectively. There are no recognizable protein motifs or domains in the molecules. Furthermore, all three molecules are predicted to be soluble proteins. Homology searches have identified sequences from multiple species that exhibit a high degree of amino acid identity with the human sequences reported here (Figure 2). hVps26 shows a high degree of end-to-end homology with proteins from several species, including C. elegans, Drosophila melanogaster, Arabidopsis thaliana, and S. cerevisiae. Vps35 is also well conserved throughout evolution. Based on the amino acid identity among the various Vps35 orthologs, the protein contains at least three conserved regions (Nothwehr et al., 1999). Interestingly, in addition to having orthologs in C. elegans, and S. cerevisiae, Vps29 is also found in one thermophilic bacterium (Thermatoga maritima) and several species of Archae (Methanococcus jannaschii, Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum, Pyrococcus abyssi, and Pyrococcus horikoshii). Northern blot analyses show that hVps26, hVps29, and hVps35 mRNAs are ubiquitously expressed, with hVps26 and hVps35 mRNAs being most highly expressed in heart, skeletal muscle, kidney, liver, and placenta. In addition to these tissues, hVps29 mRNA is also highly expressed in spleen, thymus, and peripheral leukocytes (Figure 3).

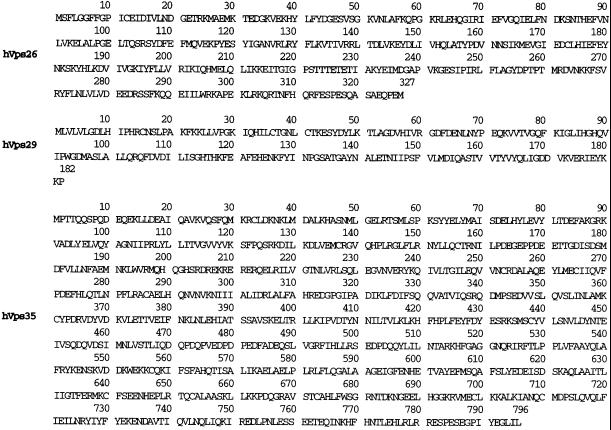

Figure 1.

Amino acid sequences of human retromer proteins. Shown are the deduced amino acid sequences for human Vps26, Vps29, and Vps35 (accession number AF175266, AF175264, and AF175265, respectively). The predicted sizes of 36, 20, and 87 kDa for hVps26, hVps29, and hVps35, respectively, correspond very well with the size of each protein seen by Western blotting.

Figure 2.

Human Vps26, Vps29, and Vps35 are evolutionarily well conserved. Shown are schematic illustrations of the predicted domain architecture of human (h) Vps26, Vps29, and Vps35, and related proteins from C. elegans (ce), S. cerevisiae (se), Schizosaccharomyces pombe (sp), mouse (m), A. thaliana (at), D. melanogaster (dm), Dictyostelium discoideum (dd), M. jannaschii (mj), M. thermoautotrophicum (mb), T. maritima (t), and P. abyssi (p). The accession numbers of the homologous molecules are as follows: mVps26, P40336; dmVps26, T12683, ceVps26, O01258; ddVps26, AAB03668; atVps26, T05874; spVps26, Q10243; scVps26, NP004887; mVps29, AF193794; dmVps29, AAF51410; atVps29, T07720; ceVps29, T27697; scVps29, NP011876; mjVps29, Q58040; mbVps29, O27802; tVps29, D72296; pVps29, H75143; Mem3, NP032608, ceVps35, T34314; atVps35, AAB80794; scVps35, NP012381; spVps35, T11719. The percentage of amino acid identity between each human protein and related proteins from other species as determined by CLUSTAL W alignment program (Thompson et al., 1994) is shown below the various domains of the proteins.

Figure 3.

hVps35, hVps29, and hVps26 are ubiquitously expressed. The tissue distributions of hVps26, hVps29, and hVps35 mRNAs are shown. Filters containing poly(A)+ RNA from the indicated human tissues were hybridized with radiolabeled human Vps26, Vps29, and Vps35 probes. Single messages of ∼3 and ∼1.2 kDa were found for hVps26 and hVps29, respectively. Two mRNA species were found for hVps35. The more abundant form migrated at ∼3.4 kDa and the less abundant form at ∼3 kDa. The apparent mRNA sizes seen for hVps26, hVps29, and hVps35 are within the range expected when the 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions observed in several cDNA clones are added to the predicted coding sequence for each molecule.

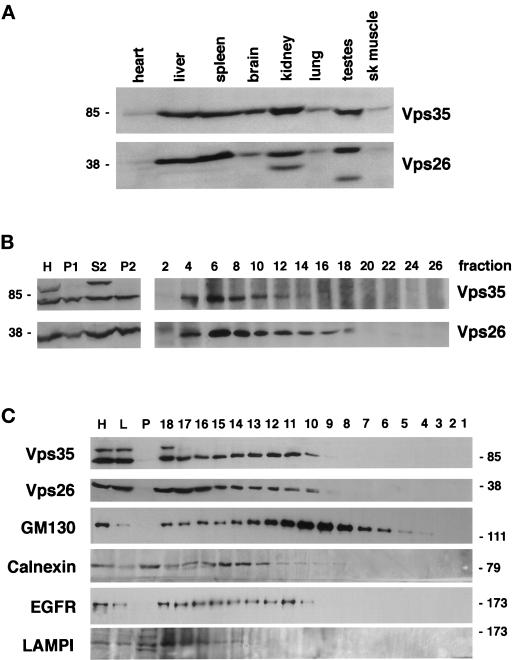

Western blot analyses of extracts from various rat organs showed that Vps35 and Vps26 protein are expressed at similar levels in all tissues examined (Figure 4A), whereas endogenous rat Vps29 is not readily detected in tissue extracts with the reagents currently available (our unpublished results). Rat Vps35 and Vps26 are expressed at low levels in heart and skeletal muscle, moderate levels in brain and lung, and the highest levels in liver, spleen, kidney, and testes. Based on the deduced amino acid sequences of Vps35, Vps29, and Vps26, the molecules are predicted to be soluble proteins. However, analyses of cytosolic and sedimentable fractions from rat liver (Figure 4B) and COS7 cells (our unpublished results) showed that the proteins were detected in both cytosolic and sedimentable fractions as judged by immunoblotting with polyclonal antibodies generated against GST fusion proteins of each molecule. In addition, sedimentation of a rat liver microsomal fraction through a linear sucrose gradient showed that both Vps35 and Vps26 entered the gradient and were enriched in the early fractions (F6–F12). These fractions also contain EEA1, an early endosomal marker, and GM130, a Golgi marker. Small amounts of Vps35 and Vps26 were also detected in regions of the gradient containing EGF receptor, a plasma membrane marker, and calnexin, an endoplasmic reticulum marker (F14–F18). No detectable Vps35 and Vps26 were found in the heavier fractions containing LAMPI, a late endosomal and lysosomal marker. These data suggest that the mammalian retromer proteins exist in both a membrane-associated and cytosolic pools. However, because large protein aggregates may also sediment partially into a sucrose gradient loaded from the top, we performed a floatation analysis. Liver homogenate was prepared and made dense. The homogenate was then overlaid with a linear sucrose gradient and centrifuged. Western blot analyses of the material that pelleted (P), the material remaining in the load following centrifugation (L), and the material floating into the gradient (fractions 1–18) showed that 22–30% of the loaded Vps35 and Vps26 floated into the gradient and thus was membrane associated (Figure 4C). We also determined the percentages of various markers that floated under our conditions: Golgi membranes containing GM130, ∼80%; ER membranes containing calnexin, ∼ 50%; and plasma membrane-derived vesicles containing the EGF receptor, ∼45%. These data suggest that at least ∼25% of rat liver Vps35 and Vps26 are membrane associated, whereas the remainder is in the cytosol in large complexes (see below). However, given that 45–80% of known organelle marker proteins floated under the conditions used rather than 100% of each marker, it is possible that as much as ∼50% of the cellular Vps35 and Vps26 are truly membrane associated.

Figure 4.

hVps35, hVps29, and hVps26 are found in both cytosolic and membrane-associated pools. (A) Distribution of hVps35 and hVps26 proteins in the indicated rat tissues as determined by immunoblotting of the various tissue extracts (∼10 μg of total protein) with molecule-specific polyclonal antibodies and anti-rabbit-horseradish peroxidase. (B) Subcellular distribution of endogenous retromer proteins in various rat liver fractions and on a linear sucrose gradient through which a microsomal fraction was sedimented as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS. Aliquots of liver homogenate (H), nuclei and unbroken cells (P1), a cytosolic fraction (S2), and a microsomal pellet (P2) were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-Vps35 and anti-Vps26 polyclonal antibodies. The distribution of hVps35 and hVps26 proteins in gradient fractions collected from rat liver microsomes separated on a linear sucrose gradient (1.06–1.25 g/ml) are also shown. The indicated gradient fractions (600 μl) were immunoprecipitated with Vps35- and Vps26-specific polyclonal antibodies, and the distribution of each protein in the various fractions determined. Fractions 1–4 contained material that remained in the load, fractions 5–10 are enriched in endosomes (EEA1 positive); fractions 13–18 are enriched in Golgi membranes (GM130 positive); fractions 18–21 are enriched in plasma membrane and endoplasmic reticulum (epidermal growth factor receptor and calnexin positive, respectively); and fractions 22–30 are enriched in lysosomes (LAMPI positive) and mitochondria as determined by immunoblotting for the indicated marker proteins (our unpublished results). (C) Floatation analysis of total rat liver homogenate. An aliquot of the starting dense homogenate (H), the material remaining in the load after centrifugation (L), the material that pelleted after centrifugation, and each gradient fraction were analyzed by Western blotting with the antibodies indicated. Fraction 18 is the heaviest fraction and closest to the load, whereas fraction 1 is the lightest fraction at the top of the gradient.

Associations of SNX1 and SNX2 with Human Vps26, Vps29, and Vps35 in Mammalian Cells

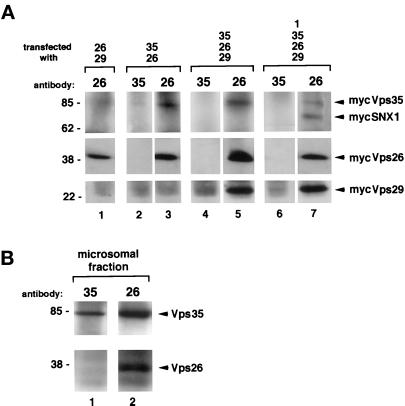

In yeast, the retromer complex contains at least five proteins: Vps35p, Vps17p, Vps26p, Vps29p, and Vps5p, the ortholog of mammalian SNX1 and SNX2 (Horazdovsky et al., 1997; Seaman et al., 1998). We inquired whether a similar complex is formed in mammalian cells. Total cell homogenates were made in the absence of detergent from COS7 cells coexpressing various combinations of myc-tagged SNX1, hVps35, hVps29, and hVps26, and incubated with antibodies generated against the various molecules. Interestingly, antibodies to hVps26 immunoadsorbed hVps35, hVps29, and SNX1, as well as hVps26 (Figure 5A, lanes 3, 5, and 7). In contrast, antibodies to hVps35 brought down no detectable hVps26, hVps29, or SNX1, and only small amounts of hVps35 (seen on darker exposures), (Figure 5A, lanes 2, 4, and 6). These data suggest that recombinant mammalian retromer proteins can form complexes in COS7 cells. These data, however, do not demonstrate whether the complexes are formed in the cytoplasm, on membranes, or both. To address this point, we immunoadsorbed a rat liver microsomal fraction with either anti-Vps35 or anti-Vps26 antibodies (Figure 5B). As seen for the transfected proteins, antibodies to Vps26 immunoadsorbed endogenous Vps35, as well as endogenous Vps26 (Figure 5B, lane 2), whereas antibodies to Vps35 brought down only small amounts of Vps35 (seen on darker exposures) and no detectable Vps26 (Figure 5B, lane 1). Similar results were obtained in immunoadsorptions from cytosol and from light fractions (1.06–1.11 g/ml) obtained after linear sucrose gradient fractionation of microsomes (our unpublished results).

Figure 5.

Coimmunoprecipitation of hVps35, hVps29, hVps26, and SNX1. (A) COS7 cells were transiently transfected with expression vectors encoding myc-tagged Vps35, Vps26, Vps29, and SNX1 as indicated. Total cell extracts were prepared in the absence of detergent and then immunoabsorbed with the indicated polyclonal antibodies followed by protein A Sepharose. Immune complexes were collected, washed, and subjected to electrophoresis followed by immunoblotting with an anti-myc antibody. (B) Microsomal fraction prepared from rat liver was immunoabsorbed, and the samples treated as described in A, expect that the immunoblots were probed with antibodies to hVps35 and hVps26 to detect the amount of each endogenous protein that was immuno-isolated.

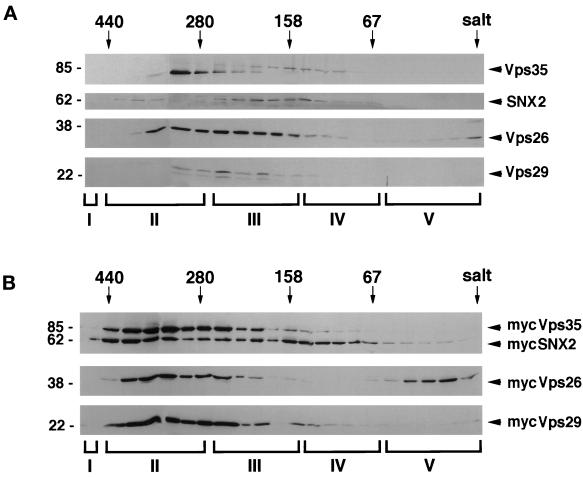

To further investigate the type(s) of complex(es) that is formed in the cytoplasm by the various mammalian retromer proteins, a cytosolic fraction prepared from COS7 cells was separated on a Sephacryl S-300 gel filtration column. Proteins in each fraction were precipitated with trichloroacetic acid and analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting with polyclonal antibodies against the various retromer proteins. Little, if any, of the endogenous proteins present in COS7 cell cytosol was detected in column fractions at the size predicted for monomers. On the immunoblot, anti-hVps35 antibodies detect two bands. The faster migrating band elutes in the range corresponding to ∼200–300 kDa, whereas the slower migrating band elutes from the Sephacryl S-300 column at somewhat smaller size (Figure 6A). It is not clear why Vps35 appears as a doublet, but it is possible that the faster migrating band may be a proteolytic fragment of the protein generated during the analysis, or the result of variable splicing or posttranslational modification. The majority of endogenous SNX2, Vps26, and Vps29 have overlapping elution profiles with endogenous Vps35. In addition, a small amount of Vps26 elutes from the column at a small size corresponding to the predicted size for monomeric Vps26. Similar results were found with endogenous proteins in rat liver cytosol (our unpublished results). Gel filtration analyses of cytosolic fractions prepared from COS7 cells overexpressing myc-tagged hVps35, hVps29, hVps26, and SNX2 also showed that the transfected proteins formed large complexes. However, the complexes tended to be larger with cytosol prepared from COS7 cells overexpressing the various myc-tagged proteins (Figure 6B). In addition, a portion of the myc-SNX2 and myc-hVps26 also eluted in fractions at the size predicted for monomers. Interestingly, the evidence suggests that the complexes (containing endogenous or recombinant proteins) are heterogeneous with respect to stoichiometry and composition.

Figure 6.

hVps26, hVps29, and hVps35 are found in a large complex. (A) Cell extract was prepared from nontransfected COS7 cells in the absence of detergent as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS. The extract was centrifuged at 240,000 × g for 45 min, and the resulting supernatant was chromatographed on a Sephacryl S-300 gel filtration column. The proteins in each fraction were precipitated with trichloroacetic acid, and analyzed for the presence of hVps26, hVps29, hVps35, and SNX2 by immunoblotting with antibodies made against the various proteins. The resulting autoradiograms were scanned, and the density of the bands quantified by using the NIH Image software. Arrows show the positions of marker proteins used to calibrate the column (thyroglobulin [669 kDa], ferritin [440 kDa], γ-globulin [158 kDa], bovine serum albumin [67 kDa]). (B) Cytosolic fraction prepared from COS7 cells transiently transfected with expression vectors encoding myc-tagged hVps26, hVps29, hVps35, and SNX2 was chromatographed, and the fractions treated as detailed above except that the immunoblots were probed with an anti-myc antibody to detect the overexpressed proteins. Pool I (fractions 1–13) contains molecules that elute at sizes between 103 and 440 kDa; pool II (fractions 14–18) contains molecules eluting between 440 and 280 kDa; pool III (fractions 19–24) contains molecules eluting between 280 and 158 kDa; pool IV (fractions 25–29) contains molecules eluting between 158 and 67 kDa; and pool V (fractions 30–35) contains molecules eluting at <67 kDa.

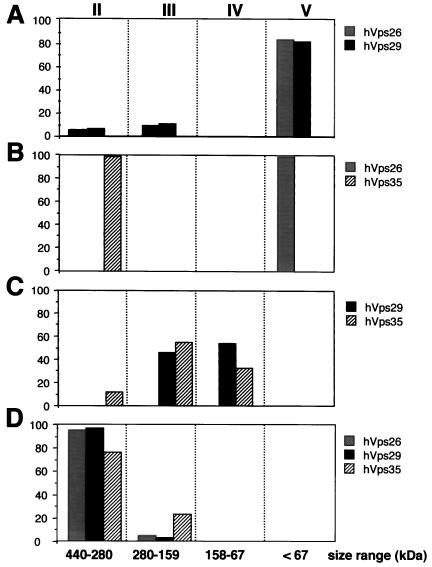

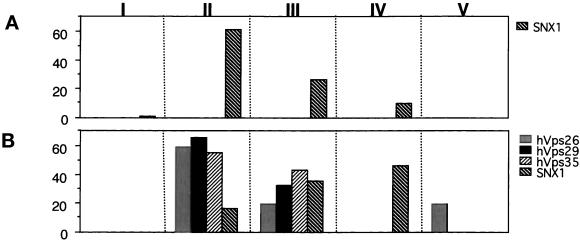

To gain insight into how the various retromer proteins might assemble into the cytosolic complexes, we used the COS7 cell overexpression system as our model. We expressed various combinations of myc-tagged SNX1, hVps35, hVps29, and hVps26 in COS7 cells and then examined the elution profiles of each protein to define the requirements for assembly. When myc-tagged hVps29 and hVps26 were expressed alone (our unpublished results) or in combination (Figure 7A), both molecules eluted in pool V at positions consistent with the deduced masses of the monomers. Moreover, when hVps35 was expressed alone or in combination with hVps26 (Figure 7B), hVps35 eluted at ∼220–300 kDa (Figure 7B, pool II), whereas hVps26 eluted as a monomer (Figure 7B, pool V). However, under these conditions very little hVps35 was detected in the cytosolic fraction. In contrast, when hVps35 was coexpressed with hVps29 (Figure 7C), the level of hVps35 in the cytosolic fraction was substantially higher, and both proteins eluted with a distribution centered at ∼220 kDa, a size much larger than either protein's predicted monomeric weight. These findings suggest that when hVps35 and hVps29 are coexpressed they are part of a multimeric complex in the cytosol (Figure 7C, pools III and IV). Lastly, when hVps35, hVps29, and hVps26 were expressed together, all three molecules coeluted at a position corresponding to high molecular masses (∼280–440 kDa), suggesting that they form a multimeric protein complex (Figure 7D, pool II). Interestingly, when SNX1 was expressed alone (Figure 8A) or in combination with one of the other retromer proteins, it eluted exclusively as large oligomers (∼440–158 kDa). The expression of recombinant SNX1 along with various pairs of the other retromer proteins also had no effect on the elution profiles of the recombinant molecules (our unpublished results). However, coexpression of all four molecules together shifted the elution position of some of the SNX1 to a smaller size. Most of the SNX1 eluted in pool II when expressed by itself. In contrast, most of the SNX1 eluted in pools III and IV when expressed in the presence of hVps26, hVps29, and hVps35. The coelution of all four molecules in pools II and III suggests that they may all be present in the same multimeric complexes. However, the ratios of the various retromer proteins are strikingly different in the two pools, suggesting that the complexes may be heterogeneous with respect to the stoichiometry of subunit composition.

Figure 7.

hVps29 and hVps35 form a cytosolic complex in the absence of hVps26. Cytosolic fractions were prepared from COS7 cells overexpressing cDNAs encoding myc-tagged hVps26 and hVps29 (A); hVps26 and hVps35 (B); hVps29 and hVps35 (C); and hVps26, hVps29, and hVps35 (D). Cell extracts were then prepared, chromatographed, and analyzed as described in Figure 6. Shown is the distribution of each myc-tagged molecule in the pools of various sizes. The signal detected in the various pools is expressed as a percentage of the total immunodetectable signal in all the column fractions.

Figure 8.

SNX1 forms large oligomeric complexes in the absence the other retromer proteins. Cytosolic fractions were prepared from COS7 cells overexpressing cDNAs encoding myc-tagged SNX1 (A) and SNX1, hVps26, hVps29, and hVps35 (B). Cell extracts were then prepared, chromatographed, and analyzed as described in Figure 6. Shown is the distribution of each myc-tagged molecule in the pools of various sizes. The signal detected in the various pools is expressed as a percentage of the total immunodetectable signal in all the column fractions.

Associations among Human Retromer Proteins in the Yeast Two-Hybrid System

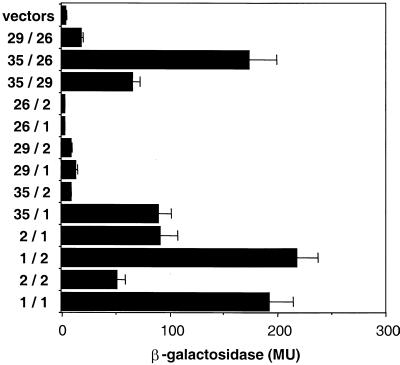

We next used the yeast two-hybrid system to define the binary interactions between the retromer proteins and thereby elucidate the interactions leading to assembly of the retromer complex. Two-hybrid analyses confirmed previous coimmunoprecipitation studies (Haft et al., 1998), demonstrating that SNX1 and SNX2 associate to form both homo- and heterodimers (Figure 9). In addition, hVps35 participates in binding interactions with SNX1, hVps26, and hVps29. These data suggest that hVps35 can serve as the nucleus for a multimeric complex containing SNX1, hVps26, and hVps35. We also observed several weak binary interactions that may provide additional driving forces to stabilize the complex: hVps26 with hVps29, hVps29 with SNX1, and hVps29 with SNX2.

Figure 9.

Interactions of human retromer proteins with each other and SNX1 and SNX2. Full-length SNX1, SNX2, hVps26, hVps29, and hVps35 were fused to either the LexA DNA-binding domain in the pLexA vector or the B42 activation domain in the pB42AD vector as indicated. Interactions were assessed by using a liquid β-galactosidase assay and reported in Miller units (MU). Results are presented as mean ± SE of data obtained with 12–20 independent yeast clones.

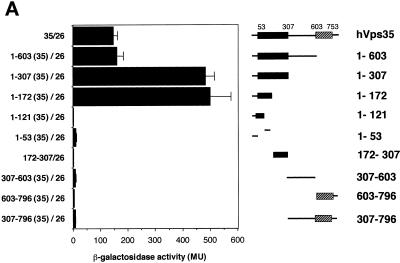

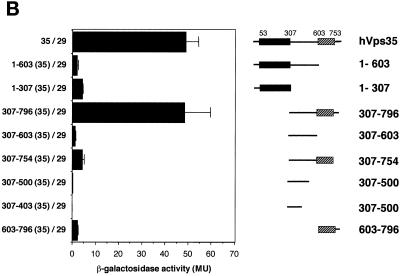

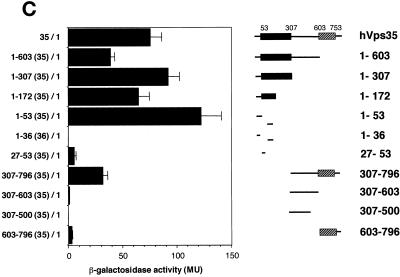

We next designed experiments to map the binding sites on hVps35 for other retromer proteins. Homology searches using the human Vps35 amino acid sequence showed that hVps35 has at least three regions that are well conserved throughout evolution (Figure 2): region I (amino acid residues 54–307), region II (residues 307–603), and region III (residues 603–753). We hypothesized that the conserved sequences corresponded to functional domains, and used this information to carry out deletional analyses of the hVps35 molecule. Two-hybrid analyses performed using these deletion constructs showed that hVps26 interacts strongly with amino acid residues 1–172 of hVps35 (Figure 10A), but only weakly with other parts of the hVps35 molecule. Further deletion of the 1–172 fragment abolished the interaction with hVps35. In contrast, hVps29 shows only a weak interaction with the N-terminal portion of hVps35 (amino acids 1–307), but shows a strong interaction with amino acid residues 307–796 (Figure 10B). Additional truncation of hVps35 from either end abolished interactions with hVps29. Lastly, SNX1 interacted strongly with two regions of hVps35: amino acid residues 1–53 and 307–796 of hVps35 (Figure 10C). Furthermore, deletional analyses of SNX1 showed that amino acid residues 1–53 and 307–796 of hVps35 interacted with the C-terminal region of SNX1, predicted to possess three coiled-coils. In contrast, neither the N-terminal nor the phox homology domains of SNX1 showed detectable associations with hVps35 or its deletion mutants (our unpublished results).

Figure 10.

Different regions of hVps35 bind to hVps26, hVps35, and SNX1. The experiments were carried out as described in the legend to Figure 9. (A) Interactions of the pB42AD-hVps26 fusion proteins with pLexA fusion proteins containing the indicated fragments of hVps35. (B) Interactions of pB42AD-hVps29 fusion protein with pLexA fusion proteins containing the indicated fragments of hVps35. (C) Interactions of SNX1 fused to pB42AD with pLexA fusion proteins containing the indicated fragments of hVps35. Results are presented as means ± SE of data obtained with 9–20 independent yeast clones.

DISCUSSION

Human Retromer Proteins

Previous work in S. cerevisiae has shown that five proteins, Vps5p, Vps17p, Vps26p, Vps29p, and Vps35p, are part of a multimeric protein complex termed the retromer complex (Nothwehr and Hindes, 1997; Seaman et al., 1997, 1998). It has been proposed that the retromer complex acts as a novel coat that directs retrograde transport of proteins from prevacuolar endosomes back to the late-Golgi. Sorting nexins 1 and 2, two closely related human orthologs of yeast Vps5p, are the only mammalian retromer proteins studied to date. They form homo- and hetero-oligomers, and have been shown to associate with a number of different receptors (Haft et al., 1998). Here we describe three additional human retromer proteins, hVps35, hVps29, and hVps26, and define the protein-protein interactions that allow them to assemble into a multimeric complex.

Like SNX1 and SNX2, hVps26, hVps29, and hVps35 share a high degree of sequence similarity with their orthologs in insects, C. elegans, and yeast (Haft et al., 1998; Nothwehr et al., 1999). Northern blot analyses show that the levels of hVps35 and hVps26 mRNA closely parallel each other in the tissues examined. However, hVps29 mRNA is strongly expressed in several tissues (i.e., colon, thymus, spleen, and peripheral leukocytes) where mRNAs for hVps35 and hVps26 are expressed at much lower levels. Although mRNA levels do not necessarily directly correlate with the level of protein expression, these data suggest that hVps29 may have functions in addition to the role it plays as part of the retromer complex. Interestingly, hVps29 orthologs are present in several prokaryotic species of Archae and one thermophilic bacterium. Because prokaryotes do not have organelles, prokaryotic Vps29 may have an alternative function that might be operating in some mammalian tissues or cell types such as T or B lymphocytes. Presently, no function has been assigned to prokaryotic Vps29. However, deletion of the gene for mouse Vps26 is embryonic lethal at day 8.5–9 (Radice et al., 1991; Bachhawat et al., 1994). In yeast, inactivation of a single component of the retromer complex disrupts the functioning of the complex (Horazdovsky et al., 1997; Seaman et al., 1997). The lethal effects of ablating mouse Vps26 indicate that the complex also serves an essential function in mammals.

Human Retromer Proteins Form Large Complexes in Cells

We have shown here that endogenous mammalian retromer proteins, as well as recombinant molecules expressed in COS7 cells, form multimeric complexes in vivo. Several findings support this conclusion. When membrane fractions were immunoadsorbed by anti-Vps26 antibodies, the membranes isolated were found to contain Vps35, Vps29, and SNX1, in addition to Vps26. These findings demonstrate that these proteins are located on the same membranes, and suggest, but do not directly demonstrate, that the molecules are in a multimeric complex. Surprisingly, anti-Vps35 antibodies were relatively ineffective at binding Vps35 in these same fractions. It is possible that we don't detect the complex when Vps35 antibodies are used as the immunoadsorbant because these antibodies have a lower affinity for Vps35 than the Vps26 antibodies have for Vps26. However, we are able to immunoprecipitate Vps35 in the presence of detergent. Based on our two-hybrid data, immunoadsorption and immunoprecipitation studies, we favor the interpretation that Vps35 is at the core of the complex bound to Vps26, Vps29, and SNX1, and thus is inaccessible to added antibodies. In contrast, Vps26 is on the outside of the complex where it can interact with antibodies.

Immunoprecipitation of a multiprotein complex from detergent-solubilized membranes has proved difficult, possibly because detergent may disrupt the complex. Nevertheless, gel filtration analyses of cytosol from a number of sources showed that hVps35, hVps29, hVps26, and SNX1/2 are found in the cytosol as part of a large complex (∼220–440 kDa). These data are consistent with cross-linking studies done in yeast that showed that Vps5p, the ortholog of SNX1 and SNX2, forms a complex with Vps35p, Vps29p, Vps26p, and Vps17p (Seaman et al., 1998). Presently, a mammalian ortholog of yeast Vps17p has not been identified (Kohrer and Emr, 1993). However, humans express a variety of SNXs that like Vps17p, contain phox homology domains. It is possible that one of these proteins (e.g., SNX2) plays the role of Vps17p in higher eukaryotes. Completion of the sequencing of the human genome will help to address this question.

Like Vps5p, recombinant SNX1 and SNX2 also show a propensity to aggregate, forming large complexes (∼220–440 kDa) in the cytosol of COS7 cells when overexpressed. Interestingly, when hVps26, hVps29, and hVps35 are all coexpressed with either SNX1 or SNX2, the majority of SNX1/2 coelutes with the other retromer proteins, whereas the remainder elutes at a size consistent with it existing as dimer or monomer. Formation of a complex between SNX1/2 with the other retromer proteins appears to compete with the ability of SNX1 and SNX2 to self-assemble into large complexes.

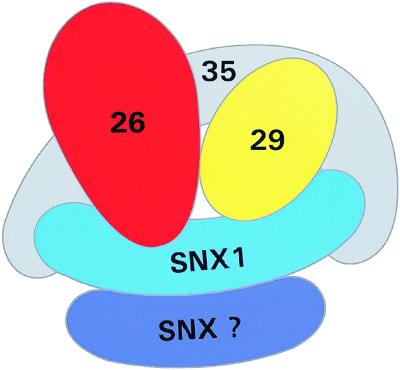

Our studies provide the first insights into the protein–protein interactions that mediate the assembly of Vps35, Vps29, Vps26, and SNX1/2 into a multisubunit complex. Using the yeast two-hybrid system, we demonstrate that hVps35 can bind directly to SNX1, hVps26, and hVps29. Therefore, hVps35 likely serves as the nucleus for assembly of the multimeric retromer complex (Figure 11). hVps26 binds to the N-terminal half of hVps35 (amino acid residues 1–172), whereas hVps29 binds to the C-terminal half of the molecule (amino acid residues 307–796). The existence of these distinct binding sites is consistent with a model in which hVps35 binds simultaneously to both hVps26 and hVps29. In addition, hVps26 and hVps29 are capable of binding directly to one another, and this interaction may further stabilize the multimeric complex.

Figure 11.

Model of binding interactions between human retromer proteins. In this model, hVps35 forms the core of a multimeric complex in which it binds directly to at least three other proteins: hVps26, hVps29, and SNX1. Furthermore, there are potential binding interactions that may stabilize the complex: hVps26 with hVps29, hVps29 with SNX1, and SNX1 with SNX1 (or another sorting nexin, designated SNX-?). In contrast, we did not detect evidence for binding of hVps26 directly to SNX 1 or SNX2. Furthermore, SNX2 does not appear to bind directly to hVps35. Although we have depicted a single molecule of SNX1 binding to both binding sites on hVps35, it is possible that each binding site on hVps35 is occupied by distinct molecules of SNX1. Our model for the mammalian retromer complex is consistent with the proposed subunit composition of the yeast retromer complex with the exception that we have not identified a human ortholog for Vps17p (see DISCUSSION).

In addition, hVps35 has two binding sites for SNX1, one in the N terminus (amino acid residues 1–53) and one in the C-terminal half of the molecule (amino acid residues 307–796). Our data do not distinguish whether a single molecule of SNX1 binds both sites on hVps35 as shown in Figure 11, or whether two molecules of SNX1 bind to hVps35, one at each binding site. In light of the ability of SNX1 to self-associate (or to associate with other sorting nexins), it is plausible that SNXs may exist as dimers when they bind to hVps35. Based on our mapping of binding sites, it is not clear whether the binding site for SNX1 overlaps the binding site for hVps26 on hVps35. However, the fact that SNX1 binds to amino acid residues 1–53 of hVps35 suggests that this short sequence is capable of folding into a functional conformation. Thus, the failure to demonstrate hVps26 binding to these N-terminal 53 amino acids suggests that hVps26 probably binds downstream at residues 54–172 of hVps35. Furthermore, the weak binding interaction between SNX1 and hVps26 supports a model in which hVps26/SNX1 binary interactions stabilize the complex in which both molecules bind simultaneously to nonoverlapping regions on hVps35. Similarly, we have succeeded in mapping binding sites for SNX1 and hVps29 to the C-terminal half of hVps35 (i.e., residues 307–796), but have not succeeded in mapping the binding sites more precisely. In addition, hVps29 and SNX1 are capable of binding to one another, an observation that supports a model in which these two molecules bind cooperatively to hVps35.

Recent studies of yeast Vps35p indicate that the N-terminal domain of Vps35p is required for proper retrieval of dipeptidyl amino peptidase A, whereas the C-terminal domain is required for efficient retrieval of Vps10p (Nothwehr et al., 1999). However, it has not yet been determined which regions of yeast Vps35p mediate its associations with other yeast retromer proteins. Likewise, additional work is required to determine whether human Vps35 is involved in cargo selection either via direct binding of cargo or by binding another protein that in turn binds to cargo. Nevertheless, given that SNX1 binds to a variety of receptor molecules (Haft et al., 1998) and also to hVps35, it is possible that SNX1 may serve to recruit receptors to the complex. Moreover, several of the 13 additional human sorting nexins deposited in GenBank have been shown to interact with SNX1 and SNX2 (our unpublished results). Thus, it is possible that a variety of protein complexes exists in the cell with slightly different compositions that function in different intracellular trafficking steps, and perhaps interact with different types of cargo.

Conclusion

Mammalian retromer proteins closely resemble their yeast orthologs in structure, and also appear to assemble into similar multimeric complexes. These structural similarities strongly suggest that they serve related functions in protein trafficking in yeast and mammals. Our studies have begun to elucidate the binding interactions responsible for assembly of mammalian retromer complexes. In light of the existence of multiple sorting nexins encoded in mammalian genomes, it seems likely that these complexes may be heterogeneous with respect to subunit composition and stoichiometry. Furthermore, this variety in the composition of the complexes may provide a basis for specificity, allowing similar complexes to function at multiple intracellular compartments in the cell.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Dr. George Poy for running of many sequencing gels. We also thank Dr. Susan Phillips for helpful discussions, and Dr. Samuel Cushman for critical reading of the manuscript. Finally, we thank Alexa Andewelt, Darren Morris, Bruce McGibbon, and Nayela Kahn for contributions to this project.

Abbreviations used:

- EEA1

early endosomal antigen 1

- GST

glutathione S-transferase

- LAMPI

lysosome-associated membrane protein I

- SNX

sorting nexin

- TGN

trans-Golgi network

- Vps

vacuolar sorting protein

REFERENCES

- Andersson S, Bishop RW, Russell DW. Expression cloning and regulation of steroid 5 alpha-reductase, an enzyme essential for male sexual differentiation. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:16249–16255. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ausubel FM, Brent R, Kingston RE, Moore DD, Seidman JG, Smith JA, Struhl K. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. Vol. 2. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1994. pp. 13.17.11–13.17.10. [Google Scholar]

- Bachhawat AK, Suhan J, Jones EW. The yeast homolog of H 58, a mouse gene essential for embryogenesis, performs a role in the delivery of proteins to the vacuole. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1379–1387. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.12.1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bankaitis VA, Johnson LM, Emr SD. Isolation of yeast mutants defective in protein targeting to the vacuole. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:9075–9079. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.23.9075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant NJ, Stevens TH. Vacuole biogenesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: protein transport pathways to the yeast vacuole. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:230–247. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.1.230-247.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn WA, Hubbard AL. Receptor-mediated endocytosis of epidermal growth factor by hepatocytes in the perfused rat liver: ligand and receptor dynamics. J Cell Biol. 1984;98:2148–2159. doi: 10.1083/jcb.98.6.2148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyuris J, Golemis E, Chertkov H, Brent R. Cdi1, a human G1 and S phase protein phosphatase that associates with Cdk2. Cell. 1993;75:791–803. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90498-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haft CR, de la Luz Sierra M, Barr VA, Haft DH, Taylor SI. Identification of a family of sorting nexin molecules and characterization of their association with receptors. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:7278–7287. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.12.7278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haft CR, Klausner RD, Taylor SI. Involvement of dileucine motifs in the internalization and degradation of the insulin receptor [published erratum appears in J. Biol. Chem. (1995) 270, 30235] J Biol Chem. 1994;269:26286–26294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horazdovsky BF, Davies BA, Seaman MN, McLaughlin SA, Yoon S, Emr SD. A sorting nexin-1 homologue, Vps5p, forms a complex with Vps17p and is required for recycling the vacuolar protein-sorting receptor. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:1529–1541. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.8.1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohrer K, Emr SD. The yeast VPS17 gene encodes a membrane-associated protein required for the sorting of soluble vacuolar hydrolases. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:559–569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurten RC, Cadena DL, Gill GN. Enhanced degradation of EGF receptors by a sorting nexin, SNX1. Science. 1996;272:1008–1010. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5264.1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurten R, Eyiuche C, Fletcher B. Biochemical and morphological evidence that SNX1 is a coat protein. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:213A. [Google Scholar]

- Lennon G, Auffray C, Polymeropoulos M, Soares MB. The I.M.A.G.E. Consortium: an integrated molecular analysis of genomes and their expression. Genomics. 1996;33:151–152. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy-Toledano R, Accili D, Taylor SI. Deletion of C-terminal 113 amino acids impairs processing and internalization of human insulin receptor: comparison of receptors expressed in CHO and NIH-3T3 cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993;1220:1–14. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(93)90090-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcusson EG, Horazdovsky BF, Cereghino JL, Gharakhanian E, Emr SD. The sorting receptor for yeast vacuolar carboxypeptidase Y is encoded by the VPS10 gene. Cell. 1994;77:579–586. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90219-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nothwehr SF, Bruinsma P, Strawn LA. Distinct domains within Vps35p mediate the retrieval of two different cargo proteins from the yeast prevacuolar/endosomal compartment. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:875–890. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.4.875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nothwehr SF, Hindes AE. The yeast VPS5/GRD2 gene encodes a sorting nexin-1-like protein required for localizing membrane proteins to the late Golgi. J Cell Sci. 1997;110:1063–1072. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.9.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novick P, Zerial M. The diversity of Rab proteins in vesicle transport. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:496–504. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radice G, Lee JJ, Costantini F. H beta 58, an insertional mutation affecting early postimplantation development of the mouse embryo. Development. 1991;111:801–811. doi: 10.1242/dev.111.3.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman JH, Stevens TH. Protein sorting in yeast: mutants defective in vacuole biogenesis mislocalize vacuolar proteins into the late secretory pathway. Cell. 1986;47:1041–1051. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90819-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaman MN, Marcusson EG, Cereghino JL, Emr SD. Endosome to Golgi retrieval of the vacuolar protein sorting receptor, Vps10p, requires the function of the VPS29, VPS30, and VPS35 gene products. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:79–92. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.1.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaman MN, McCaffery JM, Emr SD. A membrane coat complex essential for endosome-to-Golgi retrograde transport in yeast. J Cell Biol. 1998;142:665–681. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.3.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westphal V, Marcusson EG, Winther JR, Emr SD, van den Hazel HB. Multiple pathways for vacuolar sorting of yeast proteinase A. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:11865–11870. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.20.11865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zervos AS, Gyuris J, Brent R. Mxi1, a protein that specifically interacts with Max to bind Myc-Max recognition sites [published erratum appears in Cell (1994) 79, following 388] Cell. 1993;72:223–232. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90662-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]