Abstract

We established a simple and effective method for DNA immunization against Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) infection with plasmids encoding the viral PrM and E proteins and colloidal gold. Inoculation of plasmids mixed with colloidal gold induced the production of specific anti-JEV antibodies and a protective response against JEV challenge in BALB/c mice. When we compared the efficacy of different inoculation routes, the intravenous and intradermal inoculation routes were found to elicit stronger and more sustained neutralizing immune responses than intramuscular or intraperitoneal injection. After being inoculated twice, mice were found to resist challenge with 100,000 times the 50% lethal dose (LD50) of JEV (Beijing-1 strain) even when immunized with a relatively small dose of 0.5 μg of plasmid DNA. Protective passive immunity was also observed in SCID mice following transfer of splenocytes or serum from plasmid DNA- and colloidal gold-immunized BALB/c mice. The SCID mice resisted challenge with 100 times the LD50 of JEV. Analysis of histological sections detected expression of proteins encoded by plasmid DNA in the tissues of intravenously, intradermally, and intramuscularly inoculated mice 3 days after inoculation. DNA immunization with colloidal gold elicited encoded protein expression in splenocytes and might enhance immune responses in intravenously inoculated mice. This approach could be exploited to develop a novel DNA vaccine.

Japanese encephalitis is a serious mosquito-borne viral disease in southeastern and far eastern Asia. Every year, more than 35,000 cases and 10,000 deaths are reported. One third of these have occurred in China. Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV), the etiologic agent, belongs to the Flavivirus genus of the Flaviviridae family. The majority of JEV infections are subclinical. However, among patients with clinical symptoms, fatality rates range from 10% to 50% (32).

Vaccination has been observed to protect against JEV infection in humans and domestic animals (15, 49, 52). Three kinds of Japanese encephalitis vaccine have been used in Asian countries with measurable success. One is a formalin-inactivated JEV vaccine purified from infected adult mouse brain. It was developed in Japan and is currently used worldwide, including India, Korea, and Taiwan (15, 24, 32, 27). Another formalin-inactivated vaccine and a live-attenuated vaccine designated SA14-14-2 also exist, both of which are prepared from infected primary hamster kidney cells in the People's Republic of China (52). Due to regulatory issues surrounding international standards, both vaccines are only used in mainland China (14). All vaccines have effectively decreased the morbidity of Japanese encephalitis. However, the inherent risk of using the live-attenuated viral vaccines and the potential for allergic reactions with the mouse brain-derived inactivated vaccine make vaccination undesirable in some areas where the incidence of Japanese encephalitis is low (27, 35, 38, 42). Another major problem is that inactivated vaccines do not confer sufficient long-term immunity to provide effective protection (17, 24, 38). In addition, the minimum three-dose inoculation requirement makes vaccination programs costly (38). Therefore, it is imperative that a safer, more effective, and less expensive vaccine be developed to protect against JEV infection worldwide.

Several recombinant baculovirus and vaccinia virus vectors containing PrM-NS2B flavivirus genes have been developed. Expression of their encoded proteins has been observed in infected cell cultures, and they have been found to elicit specific immune responses, thereby conferring complete or partial immunity in murine models (2, 9, 22, 30, 31, 37, 44, 53). Unfortunately, recombinant vector-based vaccines are potentially problematic in humans due to the fact that antivector immune responses have been detected in several systems (8, 41). Since intramuscular injection of plasmid DNA encoding the nucleoprotein of influenza virus under the control of a eukaryotic promoter elicited virus-specific humoral and cytotoxic T-cell immune responses (50), naked DNA vaccines, which do not pose the problem of antivector immunity, have been tested against a variety of viral pathogens.

Several investigations have reported inoculation of plasmids containing a flavivirus PrM, E, or NS1 gene to elicit specific immune responses in mice (4, 6, 7, 21, 23, 26, 36, 45). The gene gun system may induce stronger immune responses in mice than syringe injection (6). However, equipment requirements and the complexity of preparing cartridges have limited its widespread use. In this study, we constructed two plasmids encoding the JEV PrM and E proteins and established a simple, more effective method for DNA immunization. Inoculation of these plasmids with colloidal gold resulted in rapid production of high titers of specific anti-JEV antibodies in BALB/c mice, above and beyond that achieved following immunization with plasmid alone. Twice-inoculated mice were found to resist challenge with 100,000 times the 50% lethal dose (LD50) of JEV (Beijing-1 strain), even those inoculated with doses as low as 0.5 μg. A comparison of the different inoculation routes revealed that both intravenous and intradermal inoculation elicited stronger and more sustained neutralizing immune responses than intramuscular or intraperitoneal injection. Histological analysis found transfected target cells in the tissues of intravenously, intradermally, and intramuscularly injected mice 3 days after inoculation. β-Galactosidase activity in adherent splenocytes isolated from BALB/c mice inoculated with plasmid pCAGLacZ was more than four times greater in colloidal gold-delivery DNA-immunized mice than in those immunized with plasmid alone.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

Vero cells were cultivated in Eagle's minimal essential medium (MEM; Nissui Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) supplemented with 5% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; Equitech-Bio Inc., Ingran, Tex.). COS-7 cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Nissui Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd.) containing 10% heat-inactivated FBS. C6/36 cells (16) were grown at 28°C in the medium used for Vero cells except that 5% FBS and 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids were added.

The Beijing-1 strain of JEV was propagated in C6/36 cells for the plaque reduction neutralization test (PRNT) and purified from the supernatant of infected Vero cells with polyethylene glycol (Mr 6,000; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) for enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The Beijing-1 strain was also propagated twice by intracerebral inoculation into suckling BALB/c mouse brain for the animal challenge test.

Colloidal gold.

A stock of 0.01% colloidal gold was made by a slight modification of the method described by Frens et al. (11). Ten milligrams of chloroauric acid (Sigma) was added to 100 ml of boiling distilled deionized water in a silicified triangular glass bottle. This solution was boiled and stirred vigorously. After 3 min, 2.5 ml of 1% trisodium citrate dihydrate (Sigma) was rapidly dropped into the boiling solution. While still being heated, the color of the solution changed from gold to faint blue within about 30 s, after which it turned dark blue. After 2 min, the color of the solution changed to a clear brilliant red, indicating the formation of monodisperse spherical particles. The solution was boiled for another 10 min to reach the reaction endpoint and then slowly cooled at room temperature. It was stored at 4°C in a tightly sealed silicified glass bottle.

Construction of plasmids expressing JEV PrM and E proteins.

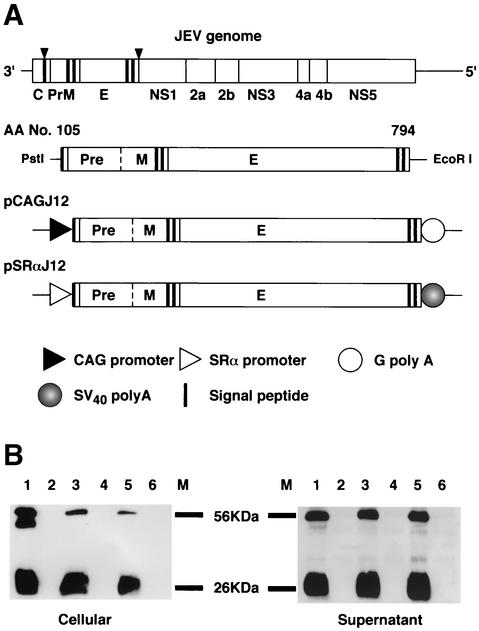

Plasmid pSLKJ12 was kindly provided by T. Sato (Biological Science Laboratory, Nippon Zeon Co. Ltd.). This plasmid contains the premembrane signal sequence as well as the premembrane (PrM) and envelope (E) genes of the Sagayama strain of JEV (44). The viral sequence, spanning nucleotides 408 to 2477, was retrieved from this plasmid by PstI-EcoRI digestion. The fragment was cloned into the eukaryotic expression vectors pcDL-SRα296 (48) and pCAGGS (34), generously provided by Y. Takebe (Laboratory of Molecular Virology and Epidemiology, AIDS Research Center, National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo, Japan) and J. Miyazaki (Division of Stem Cell Regulation Research, G6, Osaka University Medical School, Suita, Osaka, Japan), respectively. After amplifying the fragments by reverse transcription-PCR and sequencing with an ABI Prism 310 genetic analyzer (PE Biosystems, Chiba, Japan), the new constructs were designated pSRαJ12 and pCAGJ12, respectively (Fig. 1A). Plasmid DNA was extracted and purified with the Qiagen Endo-free plasmid maxi kit (Qiagen, Tokyo, Japan). Purified plasmid DNA was dissolved in 1.7% NaCl and diluted to 1.0 mg/ml prior to use. In this study, the diluted plasmid was mixed with an equal volume of 0.01% colloidal gold for inoculation into BALB/c mice.

FIG. 1.

Construction of plasmids pCAGJ12 and pSRαJ12 and identification of JEV PrM and E protein expression in vitro. (A) Schematic representation of the JEV (Sagayama strain) premembrane signal. PrM and E genes were cloned into the expression vectors pCAGGS and pcDL-SRα296. (B) Western blotting was performed to detect JEV PrM and E protein expression in transfected COS-7 cells as described in Materials and Methods. Lane 1, JEV-infected COS-7 cells. Lane 2, COS-7 cells. Lane 3, COS-7 cells transfected with pCAGJ12. Lane 4, COS-7 cells transfected with pCAGLacZ. Lane 5, COS-7 cells transfected with pSRαJ12. Lane 6, COS-7 cells transfected with pcDL-SRα296. M, molecular size markers.

Mouse experiments.

Three- or 6-week-old female BALB/c mice were purchased from SLC Co. (Tokyo, Japan). Six-week-old female SCID mice (C.B.-17/Icr Tac-scid) were obtained from Clea Co. (Tokyo, Japan). All mice were maintained in sterile cages in specific-pathogen-free environments. All experiments were conducted in accordance with the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Animals (Tokyo Metropolitan Institute for Neuroscience, 2000). Six-week-old female BALB/c mice were inoculated with the plasmid and colloidal gold mixture in a series of experiments designed to measure anti-JEV antibody production. The mice were primed on day 0 and boosted on days 9 and 22. The immunized mice were bled via the periorbital route prior to inoculation and on days 57, 92, and 144 after priming. Serum samples were stored at −80°C until used.

For the protection test, 3-week-old female BALB/c mice were inoculated with either 50, 5, or 0.5 μg of the mixture on days 0 and 9 intravenously or intradermally. On day 22, all immunized mice were challenged by an intraperitoneal injection of 100,000 times the LD50 of JEV (Beijing-1 strain, 0.15 ml), at which time they were simultaneously inoculated intracerebrally with 25 μl of saline into the right hemisphere of their brains with a 27-gauge one-stop needle (Top Injection Needle, Tokyo, Japan). Other groups of mice were also immunized with the inactivated Japanese encephalitis vaccine as described previously (6), with some modifications. A formalin-inactivated, mouse brain-propagated purified JEV (Beijing strain) vaccine obtained from Fujisawa Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Osaka, Japan), was injected with 50 μl or 100 μl (1/10th or 1/5th of the recommended adult dose, respectively) into 3-week-old female BALB/c mice intraperitoneally. Mice were boosted on day 9. On day 22, immunized mice were challenged with 100,000 times the LD50 of JEV intraperitoneally, as described above. Mice inoculated with 50 μg of empty vector DNA or 50 μl of colloidal gold alone were used as controls. All challenged mice were observed for more than 3 weeks. Postchallenge blood samples were collected from mice that survived the challenge in order to detect the production of neutralizing antibodies.

Passive immunity of colloidal gold-delivery DNA-immunized BALB/c mice was detected by a previously described method (20). Groups of five 3-week-old female BALB/c mice were immunized via intravenous or intradermal injection of 1 μg or 10 μg of plasmid pCAGJ12 along with colloidal gold. Mice were boosted on days 9 and 22 with the same dose used for priming. Control mice were inoculated with 50 μg of an empty vector plus gold colloid intravenously. Two hundred and twenty-two days after priming, splenocytes from individual mice were harvested, and red blood cells were removed from the splenocytes with 0.144 M NH4Cl-0.017 M Tris-HCl by a standard method. After washing three times with RPMI 5, cells were cultured at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 3 h. Suspended cells were transfused into five 6-week-old female SCID mice (approximately 1.7 × 107 splenocytes per mouse) intravenously. SCID mice transfused with splenocytes from BALB/c mice inoculated with an empty vector were used as controls. After 48 h, all transplanted mice were challenged with 100 times the LD50 of the Beijing-1 strain of JEV intraperitoneally and simultaneously inoculated intracerebrally with 25 μl of saline into the right hemisphere of the brain with a 27-gauge one-stop needle. Mice were observed for more than 3 weeks postchallenge.

Protective ability of the antiserum was analyzed in vivo as described previously, with some modifications (20). Five 3-week-old female BALB/c mice were inoculated with 50 μg of pCAGJ12 plus gold colloid on days 0 and 9 intravenously. On day 22, sera obtained from the immunized BALB/c mice were transferred into five 6-week-old male SCID mice (0.4 ml/mouse) intravenously. SCID mice transfused with the serum of BALB/c mice inoculated with empty vector were used as a control. Four hours after transfusion, serum-transfer SCID mice were challenged with 100 times the LD50 of JEV (Beijing-1 strain) intraperitoneally, as described above. Mice were observed for 3 weeks postchallenge.

Serological assays.

The ELISA was performed with a slight modification of a previously described method (18, 45). For production of JEV antigen, Vero cell monolayer cultures grown in 175-cm2 bottles with Eagle's MEM containing 5% FBS were infected with JEV (multiplicity of infection, ≈5). After 24 h, the medium was replaced with 20 ml of MEM containing 5% heat-inactivated FBS. At 96 h postinfection, the culture fluid was harvested and centrifuged at 10,000 × g and 4°C for 60 min. The viral solution was concentrated by addition of 40% polyethylene glycol in NTE buffer (0.12 M NaCl, 0.012 M Tris-HCl, 0.001 M disodium EDTA, pH 8.0) to a final concentration of 8% with stirring at 4°C for 18 h. The solution was recovered by centrifugation at 10,000 × g and 4°C for 60 min. The pellet was drained and dissolved in borate-saline solution (0.05 M borate, 0.12 M NaCl, pH 9.0) to concentrate it 100-fold. This antigen solution was stored at −80°C.

A round-bottomed 96-well polystyrene microtiter plate (Labsystems Oy, Helsinki, Finland) was coated with 50 μl of a 1:100 antigen dilution in borate-saline by incubation at 4°C overnight and rinsed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.2% Tween 20 (PBS-T). The plate was blocked by addition of 200 μl of 5% nonfat dry milk (Sigma) in PBS at 37°C for 2 h. After two washes with PBS-T, 50 μl of a twofold serial dilution of inactivated mouse serum (from 1:50) in PBS containing 2% nonfat dry milk was added to each well, followed by incubation at 37°C for 60 min. After washing the plate five times with PBS-T, bound proteins were detected with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG; Fc specific; 1:10,000 dilution; Sigma). After incubation at 37°C for 60 min, the plate was washed five times and further incubated at 37°C for 30 min with 100 μl of o-phenylenediamine solution (Sigma) in each well. The reaction was stopped with 20 μl of 4 M H2SO4. The absorbance at 490 nm was measured on a microplate reader (model 550; Bio-Rad Laboratory Co., Tokyo, Japan). Optical density cutoff values were established as the mean optical density plus three standard deviations for eight negative control wells containing sera from immunized control mice. A test serum was considered positive if its optical density value was greater than twice the optical density cutoff value. The endpoint titer was calculated as the reciprocal of the last dilution giving a positive optical density value.

The isotype of specific anti-JEV immunoglobulin G in the sera of immunized BALB/c mice was detected as previously described (10), with some modifications. First, 96-well microtiter plates were coated with live JEV at 4°C overnight. After blocking with 5% nonfat dry milk, plates were incubated with a twofold dilution of inactivated BALB/c mouse serum (from 1:25) that was obtained on day 22 after priming, as described above. Goat anti-mouse IgG1 and IgG2a (heavy-chain specific, 1:1,000 dilution; Sigma) and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-goat IgG (whole molecule) developed in rabbit affinity-isolated antigen-specific antibody (1:8,000 dilution; Sigma) were used as detection reagents. Absorbance at 490 nm was measured on a microplate reader (model 550; Bio-Rad Laboratory Co., Tokyo, Japan). Endpoint titers were determined as the highest serum dilution resulting in an absorbance value twice that of nonimmune serum plus three standard deviations for eight negative controls, as previously described. Samples below the limit of detection were assigned a value of zero.

PRNT.

Neutralizing antibody in the sera of inoculated BALB/c mice was detected by the PRNT test, as previously described (19, 29). To perform the neutralization test, mouse sera were serially diluted in Eagle's MEM containing 5% FBS. After heat inactivation at 56°C for 30 min, all dilutions were incubated at 37°C for 60 min with an equal volume of JEV solution (Beijing-1 strain) containing about 100 to 500 PFU/ml. Remaining infectivity in the samples was then assayed on a confluent Vero cell monolayer overlaid with Eagle's MEM containing 5% FBS and 1.25% methyl cellulose on a 24-well plate (Corning Inc.). After 5 days of incubation at 37°C with 5% CO2, cells were fixed with 10% neutral buffered formalin and stained with 0.1% crystal violet in PBS containing 20% ethanol. The neutralizing antibody titer was expressed as the maximum dilution of serum that yielded a 90% plaque reduction (PRNT90) in the virus inoculum.

Western blotting.

To detect JEV protein expression in vitro, COS-7 cells grown on 60-mm-diameter dishes were transfected with 1 μg of pCAGJ12 or PSRαJ12 plasmid with FuGene 6 (Roche). The transfected COS-7 cells were incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 72 h. The cells were washed three times with PBS and lysed with radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (0.05 M Tris, 0.15 M NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, and 0.1% aprotinin). Following centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C, the lysates were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE, 15% polyacrylamide) and transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore Co.) with transfer buffer (0.05 M Tris, 0.192 M glycine and 20% methanol) at 50 mA and 4°C for 2 h.

For detection of JEV protein secreted from transfected COS-7 cells, culture supernatant was harvested at 48 and 72 h after transfection. After centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 60 min, supernatant containing extracellular JEV PrM and E proteins was incubated with 2% nonimmune mouse serum for 2 h on ice and absorbed with 100 μl of protein G-Sepharose (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech AB, Uppsala, Sweden) at 4°C overnight. This method was performed as previously described, with some modifications (30). Unbound materials were incubated with mouse antiserum to JEV PrM and E proteins for 60 min at 4°C and then absorbed with protein G-Sepharose for 30 min. The reaction mixture was centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 30 min. The pellet was washed three times with PBS and then suspended in Laemmli electrophoresis loading buffer (25). After boiling and centrifugation, the supernatant was subjected to SDS-15% PAGE. The proteins were also transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane.

The membranes were incubated with 5% bovine serum albumin in PBS at 4°C for 2 h and then reacted with rabbit anti-JEV antiserum (53) (1:2,000 dilution in 2% bovine serum albumin washing buffer) for 60 min. After washing, the membranes were reacted with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:2,000 dilution in 2% bovine serum albumin washing buffer; Cappel) at room temperature for 60 min. The signal was visualized with an ECL Western blot kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech United Kingdom Ltd., Buckinghamshire, England). COS-7 cells infected with JEV (multiplicity of infection, ≈5) or transfected with 1 μg of empty vector in 60-mm dishes were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. Cellular lysates and supernatant were boiled with loading buffer and subjected to electrophoresis, as described above.

Histological sectioning and immunostaining.

In order to detect the expression levels of target cells in vivo, 25 μg of both pCAGJ12 and pCAGLacZ mixed with an equal volume of 0.01% gold colloid were coinoculated into 6-week-old female BALB/c mice via the intravenous, intradermal, or intramuscular route. After 72 h, spleens from mice who received intravenous injections, tails from mice who received intradermal injections, and muscle from mice who received intramuscular injections were analyzed after cryosectioning to a thickness of 10 μm. Some of the slides were fixed with 1.5% glutaraldehyde-PBS solution at room temperature for 15 min, followed by staining with a β-galactosidase staining set (Roche) at 37°C for 18 h in order to detect the β-galactosidase protein encoded by the lacZ gene. Other slides were fixed with acetone-methanol (1:1, vol/vol) at −20°C for 10 min in order to detect expression of JEV proteins with immune rabbit serum specific to JEV proteins with an indirect immunofluorescence assay (30, 53). Slides were blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (fraction V; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) in PBS at 37°C for 2 h.

The rabbit antiserum to JEV was absorbed with mouse splenic acetone powder at 4°C overnight. The absorbed serum was diluted 1:100 with PBS containing 2% bovine serum albumin and combined with JEV antigen at 37°C for 60 min. After washing five times with PBS, the slides were reblocked with normal goat serum (Cappel) at 37°C for 2 h. They were then combined with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Cappel) at 37°C for 60 min. Expression of JEV antigen was detected by fluorescence microscopy (Zeiss microscope).

Expression of plasmid administered with and without colloidal gold in vivo.

To compare the expression efficacy of plasmids inoculated with and without colloidal gold, groups of 12 6-week-old female BALB/c mice were intravenously inoculated with 50 μg of pCAGLacZ plus either 50 μl of 0.01% colloidal gold or 50 μl of distilled deionized water. Mice inoculated with 50 μl of 0.01% colloidal gold or 50 μl of distilled deionized water were used as controls. After 4 days, splenocytes from individual mice were harvested and purified, as described above. Isolated splenocytes were suspended in RPMI-5 to about 106 cells/ml and cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 3 h. After washing three times with serum-free RPMI 1640, the adherent cells were cultured for another 16 h.

Cells were harvested with a cell scraper, and β-galactosidase activity was detected with 15 mM chlorophenol red-β-galactopyranoside solution (CPRG; Roche), following a standard method. After washing three times with PBS, cells were lysed with 50 μl of RIPA buffer for 5 min on ice. The lysate was sonicated and centrifuged at 4°C and 3,000 × g for 2 min. Then 10 μl of supernatant was mixed with 100 μl of Z buffer [0.1 M Na2HPO4-NaH2PO4 buffer (pH 7.5), 10 mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO4, 50 mM β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma)]. After incubation at 37°C for 5 min, 20 μl of 15 mM CPRG solution was added and incubated at 37°C for 60 min. The reaction was stopped with 50 μl of 1 M Na2CO3. The A574 was measured with a microplate reader. The β-galactosidase activity of each sample was calculated from standard concentration curves of β-galactosidase activity (Promega, Madison, Wis.) and protein concentration.

Statistics.

Statistical analysis was conducted with Student's t test. Survival rates of challenged mice were analyzed by the Kaplan-Meier method. P values of <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Analysis of JEV PrM and E protein expression in vitro.

COS-7 cells were transfected with pCAGJ12 or pSRαJ12 with the FuGene6 transfection reagent, after which the expression of viral proteins from each plasmid was confirmed. Viral proteins within the transfected cell lysate and supernatant were detected by Western blot, as described in the Materials and Methods section. Two significant bands, one with a molecular mass of 56 kDa, representative of protein E, and the other with a molecular mass of 26 kDa, representative of PrM protein, were detected in both the cellular lysate and supernatant of COS-7 cells transfected with either pCAGJ12 or pSRαJ12. No visible bands were detected at the same location in either the cellular lysate or the supernatant of normal COS-7 cells or COS-7 cells transfected with an empty vector (Fig. 1B). These results indicate that both plasmids express the JEV PrM and E proteins in vitro. Both proteins were properly processed, glycosylated, and released into the culture medium. The proteins were then combined with specific anti-JEV antibodies. After being transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, both intracellular and secretory PrM and E proteins were recognized by rabbit antiserum specific to JEV.

Detection of JEV protein and β-galactosidase expression in tissues of colloidal gold-delivery DNA-immunized BALB/c mice.

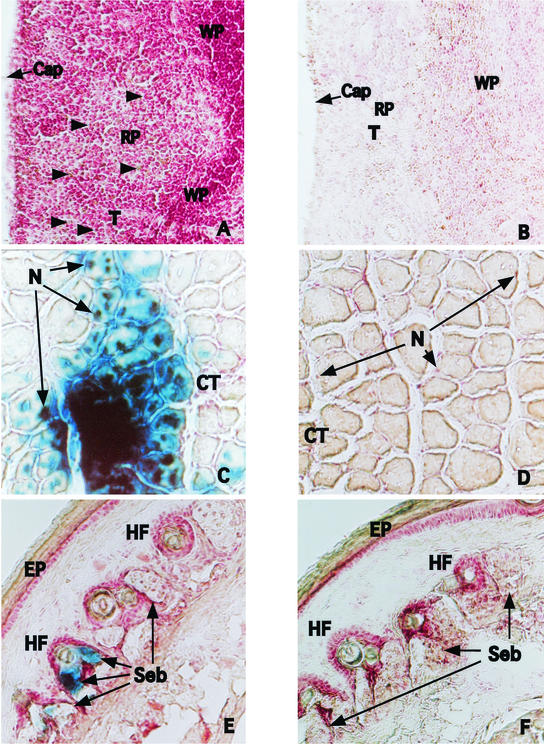

To detect JEV protein and β-galactosidase expression in vivo, groups of four 6-week-old female BALB/c mice were injected with 50 μg of plasmid (containing 25 μg of pCAGJ12 plus 25 μg of pCAGLacZ) with 50 μl of colloidal gold by the intravenous, intradermal, or intramuscular route. Mice inoculated with colloidal gold alone were used as controls. After 72 h, tissues (spleen for the intravenous route, tail for the intradermal route, and muscle for the intramuscular route) were obtained and examined by both immunofluorescence assay and β-galactosidase staining, as described in Materials and Methods.

Cryosection slides from each organ were fixed for the immunofluorescence assay with cool acetone-methanol or for β-galactosidase staining with 1.5% glutaraldehyde-PBS. Slides that were fixed with acetone-methanol were combined with rabbit anti-JEV hyperimmune serum. Fluorescein-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (Cappel) was used as the secondary antibody. Slides fixed with 1.5% glutaraldehyde were then stained with the β-galactosidase staining kit (Roche) in order to detect β-galactosidase activity. Positive signals were detected in the spleens of intravenously inoculated mice following both the immunofluorescence assay and β-galactosidase staining. Most of the positive cells were located in the red pulp area of the marginal zones (Fig. 2A and G). Positive cells were also detected in muscle tissue near the site of intramuscular injection (Fig. 2C and I). Epithelioid cells expressing JEV proteins and β-galactosidase activity were detected in the tail of intradermally inoculated mice. (Fig. 2E and K). No visible staining was detected in the control tissue.

FIG. 2.

Histological examination and immunostaining to detect antigen-expressing cells in tissues of inoculated BALB/c mice. Six-week-old female BALB/c mice were inoculated with 25 μg of pCAGJ12, 25 μg of pCAGLacZ, and an equal volume of 0.01% colloidal gold via the intravenous, intradermal, or intramuscular route. After 72 h, the organs of immunized mice (spleen from intravenously inoculated mice, tail from intradermally inoculated mice, and muscle from intramuscularly inoculated mice) were analyzed for protein expression following cryosectioning and β-galactosidase staining or immunofluorescence assay. These procedures were performed as described in Materials and Methods. The results of β-galactosidase staining are shown in panels A to F. Spleen, A and B (arrows show positive cells). Muscle, C and D. Tail, E and F. A, C, and E, plasmids plus colloidal gold; B, D, and F, distilled deionized water plus colloidal gold. The results of the immunofluorescence assay are shown in panels G to L. Spleen, G and H. Muscle, I and J. Tail, K and L. G, I, and K, plasmid plus colloidal gold; H, J, and L, distilled deionized water plus colloidal gold. Cap, capsule. CT, connective tissue. EP, epidermis. HF, hair follicles. N, nuclei. RP, red pulp. Seb, sebaceous glands. T, trabeculae. WP, white pulp.

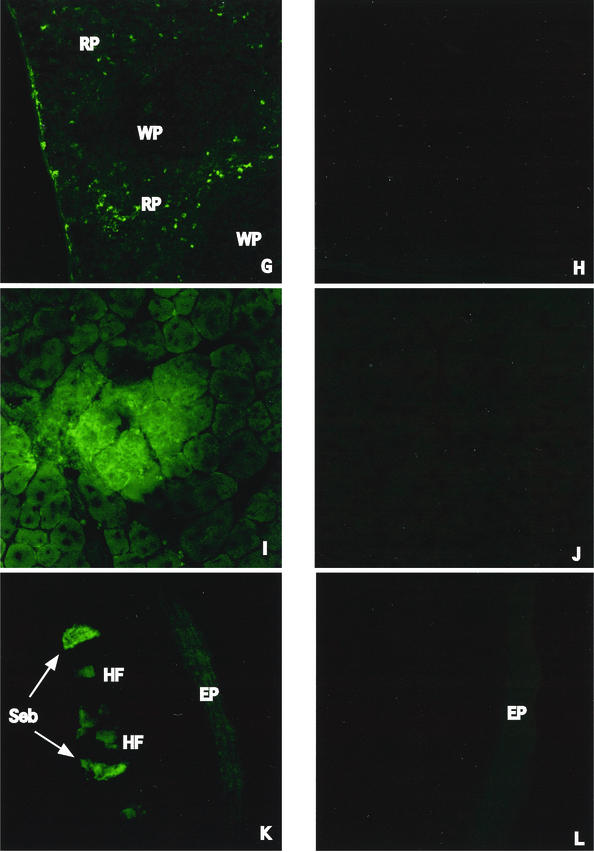

Comparison of immune response stimulation following injection of plasmid pCAGJ12 with and without colloidal gold in BALB/c mice.

Groups of four 6-week-old female BALB/c mice were intravenously injected with 50 μg of plasmid pCAGJ12 combined with an equal volume of either 0.01% colloidal gold or water. The mice were boosted on day 9. Mice inoculated with 50 μg of empty vector DNA and gold colloid were used as controls. The mice were bled by the periorbital route at approximately 1-week intervals. Specific anti-JEV antibodies were detected by ELISA and the PRNT assay as described in Materials and Methods. After boosting, anti-JEV antibodies were first detected by ELISA in the serum of BALB/c mice inoculated with pCAGJ12 plasmid and colloidal gold with a 1:800 serum dilution on day 14 and later by PRNT with a 1:80 serum dilution on day 22. Administration of plasmid pCAGJ12 without colloidal gold resulted in detection of a measurable amount of anti-JEV antibody on day 22 by ELISA (1:400) and on day 35 by PRNT (1:40) (Fig. 3). Thirty-five days after priming, there were no significant differences with regard to serum antibody concentrations among mice administered plasmid with colloidal gold and those who received plasmid alone. These results demonstrate that coadministration of plasmid and colloidal gold speeds up the production of specific anti-JEV antibodies, especially neutralizing antibodies.

FIG. 3.

Comparison of immune responses in BALB/c mice intravenously inoculated with pCAGJ12 with or without colloidal gold. Groups of four 6-week-old female BALB/c mice were intravenously immunized with 50 μg of pCAGJ12 with colloidal gold (DNA+GC) or with distilled water (DNA+DW). The mice were boosted on day 9 after priming with the same dose. Serum samples were obtained prior to injection and at 1-week intervals from days 14 to 56. Mice inoculated with the empty vector and colloidal gold (Vec+GC) were used as controls. Specific anti-JEV antibodies were detected by ELISA and PRNT, as described in Materials and Methods. Lines represent anti-JEV antibody titers as detected by ELISA. The bars show the specific neutralizing antibody titers detected by PRNT with Vero cells. The data are presented as means ± standard deviations for four animals per time point.

Determination of optimal route of inoculation.

Groups of five 6-week-old female BALB/c mice were injected with 50 μg of pCAGJ12 and colloidal gold by either the intravenous, intradermal, intramuscular, or intraperitoneal route. Mice were primed on day 0 and boosted on days 9 and 22. Blood samples were obtained via the periorbital route prior to injection and 57, 92, and 144 days after priming. Anti-JEV neutralizing antibodies were detected by the PRNT test, as described above. Specific anti-JEV antibodies were detected in all inoculated mice. Both intravenous and intradermal inoculation led to a more rapid and pronounced induction of neutralizing antibody than was observed with other routes (Fig. 4). Moreover, the antibodies produced as a result of intravenous and intradermal injection had prolonged survival over those produced by other routes of inoculation. No significant differences with regard to efficacy were observed between them.

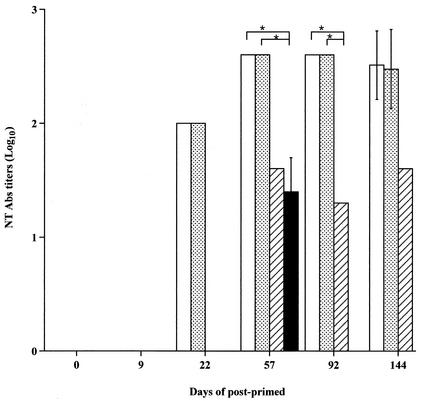

FIG. 4.

Anti-JEV neutralizing antibodies induced in BALB/c mice by inoculation via different routes. Groups of five 6-week-old female BALB/c mice were inoculated with 50 μg of pCAGJ12 and colloidal gold via intravenous (open bars), intradermal (dotted bars), intramuscular (hatched bars). or intraperitoneal (solid bars) injection. The mice were boosted on days 9 and 22 and bled by the periorbital route prior to inoculation and on days 57, 92, and 144 after priming. Specific anti-JEV neutralizing antibodies (NT Abs) were detected by PRNT as described in the text. Bars present means ± standard deviations for five animals in each group per time point. *, P < 0.05.

Intramuscular inoculation elicited neutralizing antibody production later than inoculation via the intravenous and intradermal routes. Only one mouse in the intraperitoneal inoculation group produced a detectable level of neutralizing antibody, and this was 35 days after the last boost. Significant differences were detected between the intravenous (intradermal) and intramuscular routes as well as between the intravenous (intradermal) and intraperitoneal routes (P < 0.05). Specific anti-JEV neutralizing antibodies were not detected in control mice inoculated with the empty vector and colloidal gold. These results clearly demonstrate that both intravenous and intradermal inoculation are more effective at inducing and maintaining high levels of anti-JEV neutralizing antibody in BALB/c mice than intramuscular and intraperitoneal inoculation.

Determination of effective dose for inoculation with both plasmids via intravenous and intradermal routes in BALB/c mice.

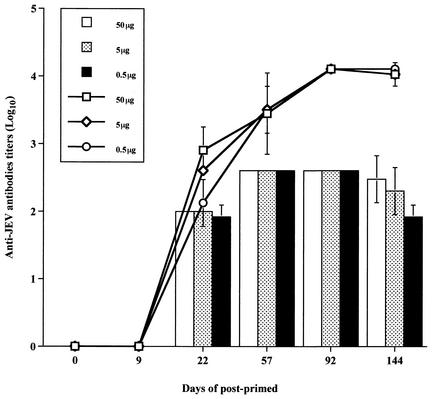

Groups of five 6-week-old female BALB/c mice were immunized with 50, 5, or 0.5 μg of pCAGJ12 and colloidal gold intravenously. The inoculated mice were boosted twice on days 9 and 22 after being primed. Blood samples were obtained on days 57, 92, and 144. Anti-JEV antibodies were detected with ELISA and PRNT as described above. Neutralizing antibodies in the sera of inoculated mice were first detected on day 22 and peaked on day 57 after priming. Antibodies continued to be detected until at least 144 days after priming. No significant differences in response were observed with any of the doses administered. Even 0.5 μg of plasmid resulted in the production of specific anti-JEV antibodies in BALB/c mice (Fig. 5). Similar results were obtained via the intradermal inoculation route following the same procedure (data not shown). With the same protocol, immunization with plasmid pSRαJ12 and colloidal gold via the intravenous or intradermal route produced an immune response similar to that observed following intravenous or intradermal administration of pCAGJ12 and colloidal gold in BALB/c mice (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Dose-dependent induction of anti-JEV antibodies in BALB/c mice. Groups of five 6-week-old BALB/c mice were intravenously primed with 50, 5, and 0.5 μg of pCAGJ12 and colloidal gold. Mice were boosted on days 9 and 22 and bled by the periorbital route prior to inoculation and on days 57, 92, and 144 after priming. Specific anti-JEV antibodies were detected by ELISA and PRNT as described in Materials and Methods. The lines represent the anti-JEV antibody titers as determined by ELISA. The bars represent the neutralizing antibody titers as detected by PRNT. Data are presented as means ± standard deviations for five animals per time point in each group. There were no significant differences among immunized mice.

Protection test.

Groups of five 3-week-old female BALB/c mice were immunized with 50, 5, or 0.5 μg of pCAGJ12 or pSRαJ12 with colloidal gold intravenously or intradermally and boosted on day 9. To compare the induction of protective immunity, a dose of 50 μl or 100 μl (1/10th and 1/5th of the recommended adult human dose, respectively) of the inactivated Japanese encephalitis vaccine was administered to mice intraperitoneally, with boosting conducted on day 9. Mice inoculated with an empty vector and colloid gold or colloidal gold alone were used as controls. On day 22 after priming, all inoculated mice were challenged with 100,000 times the LD50 of JEV (Beijing-1 strain), as described in Materials and Methods. The challenged mice were observed for more than 3 weeks. Serum samples were collected prior to challenge and after the 3-week observation period from all mice that survived the challenge.

Inoculating the mice twice elicited neutralization antibody titers of 1:20, irrespective of immunization route and prechallenge dose. All inoculated mice that received plasmid pCAGJ12 or pSRαJ12 survived the initial challenge and displayed significantly increased neutralizing antibody titers (1:400 to 1:560) at 3 weeks postchallenge. Although anti-JEV neutralizing antibodies were not detected in the prechallenge sera of inactivated Japanese encephalitis vaccine-inoculated BALB/c mice (below 1:10; Table 1), survival rates of 40% and 20% were observed in mice immunized with 100 μl or 50 μl of inactivated Japanese encephalitis vaccine, respectively. Even a 100-μl inoculation of inactivated Japanese encephalitis vaccine did not protect the mice against JEV challenge as completely as DNA plus colloidal gold immunization did. Mice inoculated with the empty vector and colloidal gold or colloidal gold alone did not have detectable levels of neutralizing antibody and died after the challenge (Table 1). These results indicate that one boost of pCAGJ12 or pSRαJ12 with colloidal gold induced a complete protective immune response to the 105 LD50 JEV challenge in BALB/c mice. No significant differences in neutralizing antibody responses or survival rates were observed between intravenous and intradermal inoculation.

TABLE 1.

Protection test of colloidal gold-delivered pCAGJ12- and pSRαJ12-immunized BALB/c mice challenged intraperitoneally with 100,000 LD50 of JEV (Beijing-1 strain)

| Inoculum | Route | Dose (μg or μl) | No. of survivors/ 5 in groupa | Neutralizing antibody titer

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prechallenge | Postchallenge | ||||

| pCAGJ12 | Intravenous | 50 | 5/5∗ | 1:20 | 1:400 |

| 5 | 5/5∗ | 1:20 | 1:560 | ||

| 0.5 | 5/5∗ | 1:20 | 1:480 | ||

| Intradermal | 50 | 5/5∗∗ | 1:20 | 1:400 | |

| 5 | 5/5∗∗ | 1:20 | 1:400 | ||

| 0.5 | 5/5∗∗ | 1:20 | 1:480 | ||

| Vector | Intravenous | 50 | 0/5 | <1:10 | |

| Intradermal | 50 | 1/5 | <1:10 | 1:20 | |

| Colloidal gold | Intravenous | 50 | 0/5 | <1:10 | |

| Intradermal | 50 | 0/5 | <1:10 | ||

| pSRαJ12 | Intravenous | 50 | 5/5∗ | 1:20 | 1:480 |

| 5 | 5/5∗ | 1:20 | 1:560 | ||

| 0.5 | 5/5∗ | 1:20 | 1:400 | ||

| Intradermal | 50 | 5/5∗ | 1:20 | 1:400 | |

| 5 | 5/5∗ | 1:20 | 1:480 | ||

| 0.5 | 5/5∗ | 1:20 | 1:560 | ||

| Vector | Intravenous | 50 | 0/5 | <1:10 | |

| Intradermal | 50 | 0/5 | <1:10 | ||

| Colloidal gold | Intravenous | 50 | 0/5 | <1:10 | |

| Intradermal | 50 | 0/5 | <1:10 | ||

| Inactivated JEV vaccine | Intraperitoneal | 100 | 2/5 | <1:10 | NDb |

| 50 | 1/5*∗∗ | <1:10 | ND | ||

∗, P < 0.01; ∗∗, P < 0.05 compared with vector-only controls; ∗∗∗, P < 0.05 compared with pCAGJ12 or pSRaJ12 plus colloidal gold groups.

ND, not done.

For analysis of the side effects of gold colloid-DNA inoculation in mice, BALB/c mice were immunized with 50 μg of pCAGJ12 with colloidal gold intravenously. Mice were boosted on days 9 and 22 and bled on day 57. The phases of blood cells were calculated with an automatic electronic blood cell counter (PCE-170; ERMA Inc., Tokyo, Japan). No significant differences in blood phases (such as blood cell count, platelet count, hematocrit, and hemoglobin count) were detected between the immunized mice and normal mice (data not shown). Furthermore, the levels of glutamate pyruvate transaminase in the sera of immunized mice were measured, and similar levels were detected in both the colloidal gold-DNA-immunized mice and normal mice (data not shown).

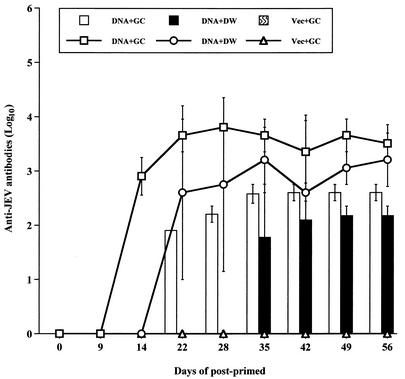

Characterization of passive protective immunity of inoculated BALB/c mice.

In order to assess passive immune function, groups of five 3-week-old female BALB/c mice were inoculated intravenously or intradermally with 10 or 1 μg of pCAGJ12 with colloidal gold. Mice were then boosted on days 9 and 22. Two hundred days after the final boost, splenocytes from the inoculated BALB/c mice were isolated and transfused into 6-week-old female SCID mice (about 1.7 × 107 splenocytes per mouse) intravenously. After 48 h, all transfused SCID mice were challenged with 100 times the LD50 of JEV (Beijing-1 strain, 0.15 ml) intraperitoneally and simultaneously inoculated intracerebrally with 25 μl of saline into the right hemisphere of the brain. All of the challenged mice were observed for more than 3 weeks.

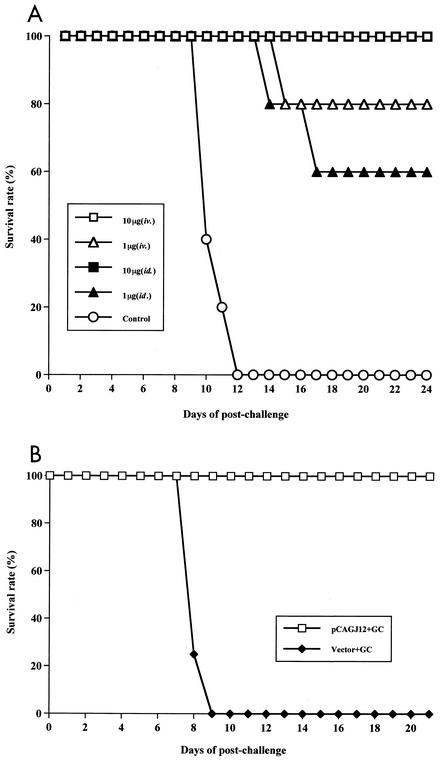

Significant differences in survival rates were discovered between the immunized and control mice (P < 0.05). Transfusion of splenocytes from mice inoculated both intravenously and intradermally with 10 μg provided complete protection (100% survived) against the 100-LD50 JEV challenge in SCID mice. Survival rates of 80% and 60% were observed for SCID mice that received splenocytes from mice inoculated with 1 μg intravenously and intradermally, respectively. No protective responses were observed in the control groups (Fig. 6A). These results indicate that the splenocytes of BALB/c mice immunized with 10 μg or 1 μg of DNA and colloidal gold conferred efficient protective immunity to transfused SCID mice against a 100-LD50 JEV challenge more than 6 months after DNA immunization.

FIG. 6.

Passive protection of SCID mice resulting from splenocyte or serum transfer from colloidal gold-DNA-immunized BALB/c mice against JEV infection. (A) Groups of five 3-week-old female BALB/c mice were inoculated with either 10 or 1 μg of pCAGJ12 and colloidal gold intravenously (iv.) or intradermally (id.). Mice were boosted twice on days 9 and 22 with the same doses and routes of administration that were used for priming. Mice inoculated with an empty vector plus colloidal gold were used as controls. Two hundred days after the last inoculation, splenocytes of immunized BALB/c mice were transfused into 6-week-old female SCID mice intravenously (1.7 × 107 splenocytes per mouse). After 48 h, the transfused SCID mice were challenged with 100 times the LD50 of JEV (Beijing-1 strain, 0.15 ml) intraperitoneally and simultaneously injected with 25 μl of saline intracerebrally as described in Materials and Methods. Survival in each group was monitored for more than 3 weeks after challenge. (B) Groups of five 3-week-old BALB/c mice were immunized with 50 μg of pCAGJ12 with gold colloid (GC) intravenously and boosted on day 9. Mice inoculated with the vector plus gold colloid were used as a control. On day 22, sera from the immunized mice were collected and heated at 56°C for 30 min. Immune sera were transfused into 6-week-old male SCID mice intravenously. After 4 h, SCID mice were challenged with 100 times the LD50 of JEV as described above. Survival in each group was monitored for 3 weeks postchallenge.

The protective ability of the sera of BALB/c mice immunized with pCAGJ12 plus colloidal gold was analyzed by intravenous transfer into 6-week-old SCID mice. After 4 h, transfused SCID mice were subjected to challenge with 100 times the LD50 of JEV intraperitoneally, as described in Materials and Methods. At the end of the observation period, all SCID mice transfused with the immune sera remained alive. All mice that received the control sera were dead within 9 days postchallenge (Fig. 6B). A significant difference was observed between these two groups (P < 0.05). These results clearly demonstrate that, within 3 weeks, the immune antiserum confers sufficient neutralizing ability to transfused SCID mice to inhibit a challenge with 100 times the LD50 of JEV.

Study of isotypes of specific anti-JEV antibody in BALB/c mice intravenously immunized with pCAGJ12 with or without gold colloid.

The different inoculation approaches and routes of antigen can result in different antibody subclasses and different T helper (Th) cell types during the immune response (1, 33). In general, Th1 immune responses promote the production of IgG2a antibody, whereas Th2 immune responses enhance the antibody production of IgG1. We analyzed the IgG isotypes produced by intravenous immunization with pCAGJ12 with or without colloidal gold in BALB/c mice. Similar titers of specific anti-JEV IgG were measured in both groups of immunized mice on day 22 after priming (data not shown). Regarding the IgG subclass profiles, the gold colloid delivery groups produced almost exclusively IgG1 anti-JEV antibody, whereas IgG2a antibody was only detected in one mouse with a lower titer (Table 2). In contrast, plasmid immunization generated higher levels of IgG2a antibody, with only low titers of IgG1 antibody induced (Table 2). These results suggest that the two methods of JEV DNA inoculation induced different helper T-cell responses.

TABLE 2.

Isotype of anti-JEV IgG titers in serum of BALB/c mice inoculated with 50 μg of pCAGJ12 with or without gold colloid intravenously on day 22 post-intravenous priminga

| Inoculation with pCAGJ12 plus: | Titer (log10)

|

IgG1/IgG2a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IgG1 | IgG2a | ||

| Gold colloid | 2.15 ± 0.15 | 0.35 ± 0.35 | 6.14 |

| Distilled water | 0.70 ± 0.40 | 2.15 ± 0.15 | 0.33 |

The data are presented as means ± standard deviations for four animals in each group.

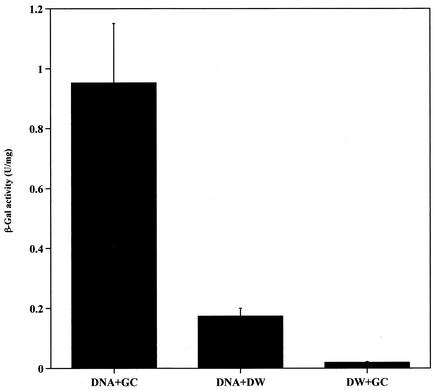

Measurement of β-galactosidase activity in adherent splenocytes of immunized mice.

To measure β-galactosidase activity, groups of 12 6-week-old female BALB/c mice were intravenously inoculated with 50 μg of pCAGLacZ with or without colloidal gold. Mice inoculated with colloidal gold alone were used as controls. The β-galactosidase activity of each sample was detected as described above. β-Galactosidase activity in the colloidal gold inoculation group was more than four times that of the group inoculated with plasmid alone. The lowest level of β-galactosidase activity was measured in control mice (Fig. 7). These results clearly demonstrate that colloidal gold is able to enhance the expression efficiency of β-galactosidase in vivo, particularly in antigen-presenting cells.

FIG. 7.

Measurement of β-galactosidase activity in adherent splenocytes of immunized BALB/c mice in vitro. Groups of 12 6-week-old female BALB/c mice were inoculated with 50 μg of pCAGLacZ with or without gold colloid (GC) intravenously. Mice inoculated with 50 μl of colloidal gold and distilled water (DW) alone were used as controls. After 4 days, the adherent splenocytes were cultured at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 16 h and lysed with RIPA buffer. The β-galactosidase activity of adherent splenocytes was detected by a unified assay, as described in Materials and Methods. Bars present means ± standard deviations for 12 animals in each group.

DISCUSSION

JEV is a single-stranded, positive-sense RNA virus, approximately 11 kb in length, containing an open reading frame encoding a polyprotein (39, 47). The polyprotein is cleaved into three structural proteins, a capsid (C), membrane (M) or precursor M (PrM), and envelope (E) protein, encoded by one-third of the open reading frame (near the 5′ region) and at least seven nonstructural (NS) proteins, from NS1 to NS5, which are encoded in the remainder of the open reading frame (3, 39). The E protein has been found to play an important role in inducing neutralizing antibodies and the protective immune response (18, 19). Transfer of neutralizing monoclonal antibodies to the JEV E protein to SCID mice can provide sustained protection against JEV infection (20). However, both the unglycosylated JEV E protein produced by Escherichia coli and the denatured E protein produced from virions of the West Nile virus fail to induce production of neutralizing antibodies in mice, indicating that glycosylation or the correct three-dimensional form of the protein is essential for its function (28, 51).

Inoculation of several eukaryotic expression systems encoding a series of JEV genes, ranging from PrM to NS1, elicited anti-JEV antibodies and variant protective immune responses in mice (4, 6, 23, 26, 53). Previous investigations suggest that a signal peptide, which is located upstream of the translation initiation site on the precursor gene, is responsible for introducing the PrM-E polyprotein into the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum, where the polyprotein is then made into type I transmembrane protein (43) and secreted from the cell (4). The E proteins that are expressed combine to form twin-helix particles. In the present study, both the pSRαJ12 and pCAGJ12 constructs contained JEV PrM and E genes encoded within a 690-amino-acid polyprotein (from amino acids 105 to 794), which also contained a few positively charged amino acids prior to the translation initiation site of the PrM gene. These may comprise the signal peptide (Fig. 1A). The secreted PrM and E proteins were recognized by specific anti-JEV antibodies in vitro (Fig. 1B). Inoculation of BALB/c mice with the pCAGJ12 plasmid resulted in expression of JEV protein and recognition by specific anti-JEV antibodies in tissue (Fig. 2G, I, and K).

DNA immunization has recently become a popular method for induction of specific immune responses against infectious agents, such as bacteria and viruses. Either a cellular or humoral bias of the immune response following DNA inoculation has been reported and seems to depend on several factors, including the type and form of antigen, the route and method of immunization, and the animal species being studied (4, 5, 6, 7, 10, 11, 12, 21, 23, 26, 36, 45, 50). Two kinds of DNA delivery have been attempted in mice: direct injection of naked plasmid DNA with a syringe (50), and inoculation of gold-covered plasmid with a gene gun (5, 12,). Although the gene gun requires less DNA, special equipment is required to coat the particles with DNA and to inoculate it. This results in limited use of this method. Mice inoculated with plasmid DNA with the gene gun exhibit stronger immune responses than mice inoculated by syringe delivery (6, 10, 12). Although the mechanism behind this is not well understood, it appears that gold cartridges might enhance immune responses in vivo.

The present work is the first time that syringe delivery of plasmid DNA with colloidal gold has been used to vaccinate BALB/c mice. Intravenous inoculation of plasmids encoding the PrM and E genes with colloidal gold resulted in higher titers of neutralizing antibody than inoculation with plasmid alone (Fig. 3). Specific antibodies were also detected shortly after inoculation of plasmid (pCAGcore or pCAGE1-E2) encoding the hepatitis C virus core or E1 and E2 genes with colloidal gold in BALB/c mice (Z. Zhao et al., unpublished data). Our results suggest that this is a feasible method by which to elicit a sustained specific antibody response against plasmid DNA encoding different proteins in BALB/c mice.

Several inoculation routes for syringe-mediated DNA immunization have been reported (10, 12, 21, 50). In the present study, neutralizing antibody production following immunization by different routes was examined. Both intravenous and intradermal inoculation elicited production of higher titers of neutralizing antibody more rapidly than the other routes of inoculation. Intramuscular inoculation stimulated delayed production of lower titers of neutralizing antibody. Intraperitoneal inoculation induced the lowest titers of neutralizing antibody. The immune response also appeared later and was shorter-lived than that following inoculation via the other routes (Fig. 4). Histochemical analysis showed transfected muscle fiber cells by both β-galactosidase staining and immunofluorescence assay near the intramuscular injection site (Fig. 2C and I). The form in which proteins are expressed might influence their ability to induce a neutralizing antibody response in vivo. In addition, although low titers of anti-JEV antibody were detected by ELISA in the sera of intraperitoneally immunized mice (data not shown), neutralizing antibodies were only detected in one of those mice on day 35 postinoculation (Fig. 4). In light of these results, it appears that intravenous and intradermal inoculation elicits greater production of neutralizing antibody than intramuscular or intraperitoneal inoculation in BALB/c mice.

To complement these data, we examined the efficacy of administering different doses via intravenous or intradermal injection in BALB/c mice. Specific anti-JEV neutralizing antibody in immunized mice was examined. After challenge, neutralizing antibody was greatly increased in all surviving mice, while lower antibody titers (1:20) were detected prior to challenge. Even 0.5 μg of plasmid and colloidal gold elicited high titers of neutralizing antibody and protected BALB/c mice against challenge with 100,000 times the LD50 of JEV following both intravenous and intradermal injection (Fig. 5 and Table 1). Mice were twice administered 1/5th or 1/10th the adult human dose of inactivated Japanese encephalitis vaccine with the same protocols as for DNA immunization, and although they exhibited undetectable prechallenge levels of neutralizing antibody, partial protective immunity against challenge with 100,000 times the LD50 of JEV was observed. Survival rates were, respectively, 40% and 20% at 3 weeks postchallenge (Table 1). Significant differences were detected between DNA-immunized mice and mice injected with a 1/10th dose of inactivated Japanese encephalitis vaccine (P < 0.05), whereas no significant differences were observed between the DNA-immunized mice and those receiving a 1/5th dose of Japanese encephalitis vaccine (P = 0.051). However, a 1/5th dose of JEV vaccine did not completely protect mice from JEV challenge, while DNA plus colloidal gold immunization offered complete protection (Table 1).

Two hundred days after the final inoculation, splenocytes were obtained from colloidal gold-DNA-immunized BALB/c mice and transferred into SCID mice. This transfer conferred effective passive immunity to the transfused SCID mice against challenge with 100 times the LD50 of JEV (Fig. 6A). Significant increases in neutralizing antibodies were detected in the sera of SCID mice receiving transfers that survived the initial challenge. The antibody titers detected were about 1:4 prechallenge and reached about 1:100 and 1:400 on days 7 and 14 postchallenge, respectively. Furthermore, SCID mice transfused with the sera of DNA-immunized BALB/c mice that survived a challenge with 100 times the LD50 of JEV clearly demonstrate that neutralizing antibody is a major factor in inhibiting JEV infection in vivo (Fig. 6B). However, the importance of the cellular immune response should be investigated further.

Different routes or methods of DNA immunization elicited different isotypes of specific antibody and helper T-cell types during the immune response (6, 10). For example, the syringe delivered plasmids elicited stronger Th1 immune responses in both intramuscularly and intradermally inoculated mice, while the gene gun delivery cases showed activated Th2 cell responses. In our study, the gold bead delivery DNA immunization by intravenous injection produced almost entirely IgG1 anti-JEV antibody (Table 2). The IgG1-to-IgG2a ratio was 6.14. In contrast, plasmid DNA immunization by the same route induced high levels of IgG2a anti-JEV antibody (Table 2). The IgG1-to-IgG2a ratio was 0.33. Because the Th1 immune response promotes the production of IgG2a antibody and the Th2 immune response promotes the production of IgG1 antibody (1, 31), our results demonstrate that intravenous DNA inoculation with gold colloid activated the Th2 immune response in immunized BALB/c mice, whereas immunization without gold colloid stimulated the Th1 immune response.

Examination of antigen-expressing cells in the tissues of intravenously inoculated BALB/c mice by both β-galactosidase staining and immunofluorescence revealed the predominance of antigen-expressing cells in the spleen. We also compared the distribution of antigen-expressing cells in the spleens of BALB/c mice intravenously inoculated with plasmid alone or with plasmid and colloidal gold. Most antigen-expressing cells were located in the red pulp area of the marginal zone of the spleen in plasmid and colloidal gold-delivered mice (Fig. 2A and G). Irregular distribution of antigen-expressing cells was observed in the mice administered plasmid alone (data not shown). Because B lymphocytes are primarily located within the marginal zone of the spleen, this might explain why there is rapid production of specific antibodies following inoculation with plasmid combined with colloidal gold.

Recent studies have demonstrated that dendritic cells play a critical role in the inductive immune response, including CD8+ cytotoxic T-lymphocyte, CD4+ Th1, and B-cell responses following DNA vaccination (10, 40, 46, 54). In this study, we detected antigen-expressing cells in adherent splenocytes of intravenously inoculated mice in vitro. These results indicate that plastic-adherent splenocytes are the primary antigen-expressing cells and likely include both dendritic cells and macrophages. Measurement of β-galactosidase activity in adherent splenocytes isolated from mice inoculated with colloidal gold-DNA showed several times greater β-galactosidase activity than was observed in mice inoculated with plasmid alone (Fig. 7). These results demonstrate that colloidal gold-DNA mixtures preferentially induce transgene expression in adherent splenocytes in order to elicit stronger immune responses in vivo.

This is the first report of inoculation of plasmid DNA encoding the JEV PrM and E proteins with colloidal gold to illustrate induction of a sustained neutralizing antibody response and complete protection against challenge in immunized BALB/c mice. Comparison of different inoculation routes revealed that both intravenous and intradermal inoculation elicit high titers of specific anti-JEV antibody and provided rapid protective immunity, even when only 0.5 μg of DNA was administered. Two hundred days after the third inoculation, transfusion of splenocytes conferred passive immunity to SCID mice against a challenge with 100 times the LD50 of JEV. Examination of antigen-expressing cells in the spleens of intravenously immunized mice revealed that most antigen-expressing cells were located in the red pulp areas of the marginal zone. Most of the antigen-expressing cells were found to be plastic-adherent splenocytes in vitro. Although the function and safety of colloidal gold is still not clearly understood, inoculation of plasmid DNA with colloidal gold does not require any special apparatus and elicits continuous production of high titers of antibody in mice. Thus, this method has been shown to be a very simple and efficient method of DNA immunization.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to T. Sato, Biological Science Laboratory, Nippon Zeon Co. Ltd., Japan, for providing the pSLKJ12 clone of JEV and J. Miyazaki, Division of Stem Cell Regulation Research, G6, Osaka University Medical School, Suita, Osaka, Japan, for supplying the pCAGGS vector. We also thank Y. Takebe, Laboratory of Molecular Virology and Epidemiology, AIDS Research Center, National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo, Japan, for providing pcDLSRα296. In addition, we thank S. Koike, J. Mukaigawa, and M. Miyamoto, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Tokyo Metropolitan Institute for Neuroscience, for discussion and technical assistance.

This work was partially supported by a Grant-in-Aid from the Japan Health Sciences Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbas, A. K., K. M. Murphy, and A. Sher. 1996. Functional diversity of helper T lymphocytes. Nature 383:787-793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bray, M., and C.-J. Lai. 1991. Dengue virus premembrane and membrane proteins elicit a protective immune response. Virology 185:505-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chambers, T. J., C. S. Hahn, R. Galler, and C. M. Rice. 1990. Flavivirus genome, organization, expression and replication. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 44:649-668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang, G. J., A. R. Hunt, and B. Davis. 2000. A single intramuscular injection of recombinant plasmid DNA induces protective immunity and prevents Japanese encephalitis in mice. J. Virol. 74:4244-4252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen, D., R. L. Enders, C. A. Erickson, K. F. Weis, M. W. Mcgregor, Y. Kawaoka, and L. G. Payne. 2000. Epidermal immunization by a needle-free powder delivery technology: immunogenicity of influenza vaccine and protection in mice. Nat. Med. 6:1187-1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen, H. W., C. H. Pan, M. Y. Liau, R. Jou, C. J. Tsai, H. J. Wu, Y. L. Lin, and M. H. Tao. 1999. Screening of protective antigens of Japanese encephalitis virus by DNA immunization: a comparative study with conventional viral vaccines. J. Virol. 73:10137-10145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colombage, G., R. Hall, M. Pavy, and M. Lobigs. 1998. DNA-based and alpha virus-vectored immunization with PrM and E proteins elicits long-lived and protective immunity against the flavivirus Murray Valley encephalitis virus. Virology 250:151-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cooney, E. L., A. C. Collier, P. D. Greenberg, R. W. Coombs, J. Zarling, D. E. Argitti, M. C. Hoffman, S. L. Hu, and L. Corey. 1991. Safety of and immunological response to a recombinant vaccinia virus vaccine expressing HIV envelope glycoprotein. Lancet 337:567-572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Falgout, B., M. Bray, J. J. Schlesinger, and C.-J. Lai. 1990. Immunization of mice with recombinant vaccinia virus expressing authentic dengue virus nonstructural protein NS1 protects against lethal dengue virus encephalitis. J. Virol. 64:4356-4363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feltquate, D. M., S. Heaney, R. G. Webster, and H. L. Robinson. 1997. Different T helper cell types and antibody isotypes generated by saline and gene gun DNA immunization. J. Immunol. 158:2278-2288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frens, G. 1973. Controlled nucleation for the regulation of the particle size in monodisperse gold suspension. Nat. Phys. Sci. 241:20-22. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fynan, E. F., R. G. Webster, D. H. Fuller, J. R. Haynes, J. C. Santoro, and H. L. Robinson. 1993. DNA vaccines: Protective immunizations by parenteral, mucosal, and gene-gun inoculations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:11478-11482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geoghegan, W. D., and G. A. Ackerman. 1977. Adsorption of horseradish peroxidase, ovomucoid and anti-immunoglobulin to colloidal gold for the indirect detection of concanavalin A, wheat germ agglutinin and goat anti-human immunoglobulin G on cell surfaces at the electron microscopic level: a new method, theory and application. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 25:1187-1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hennessy, S., Z. Liu, T. F. Tsai, B. L. Stron, C. M. Wan, H. L. Liu, T. X. Wu, H. J. Yu, Q. M. Liu, N. Karabatsos, W. B. Bilker, and S. B. Halstead. 1996. Effectiveness of live-attenuated Japanese encephalitis vaccine (SA14-14-2): a case-control study. Lancet 347:1583-1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoke, C. H., A. Nisalak, N. Sangawhipa, S. Jatanasen, T. Laorakapongse, B. L. Lnnis, S. Kotchasenee, J. B. Gringrich, J. Latendresse, K. Fukai, and D. S. Burke. 1988. Protection against Japanese encephalitis by inactivated vaccines. N. Engl. J. Med. 319:608-614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Igarashi, A. 1978. Isolation of a Singh's Aedes albopictus cell clone sensitive to dengue and Chikungunya viruses. J. Gen. Virol. 40:531-544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Juang, R. F., Y. Okuno, T. Fukunaga, M. Tadano, K. Fukai, K. Baba, N. Tsuda, A. Yamada, and H. Yabuuchi. 1983. Neutralizing antibody responses to Japanese encephalitis vaccine in children. Biken J. 26:25-34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kimura-Kuroda, J., and K. Yasui. 1983. Topographical analysis of antigenic determinants on envelope glycoprotein V3(E) of Japanese encephalitis virus, with monoclonal antibodies. J. Virol. 45:124-132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kimura-Kuroda, J., and K. Yasui. 1986. Antigenic comparison of envelope protein E between Japanese encephalitis virus and some other flaviviruses with monoclonal antibodies. J. Gen. Virol. 67:2663-2672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kimura-Kuroda, J., and K. Yasui. 1988. Protection of mice against Japanese encephalitis virus by passive administration with monoclonal antibodies. J. Immunol. 141:3606-3610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kochel, T., S. Wu, K. Raviprakash, P. Hobart, S. Hoffman, K. Porter, and C. Hayes. 1997. Inoculation of plasmids expressing the dengue-2 envelope gene elicit neutralizing antibodies in mice. Vaccine 15:547-552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Konishi, E., S. Pincus, B. A. Fonseca, R. E. Shope, E. Paoletti, and P. W. Mason. 1991. Comparison of protective immunity elicited by recombinant vaccinia viruses that synthesize E or NS1 of Japanese encephalitis virus. Virology 185:401-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Konishi, E., M. Yamaoka, K.-S. Win, I. Kurane, and P. W. Mason. 1998. Induction of protective immunity against Japanese encephalitis in mice by immunization with a plasmid encoding Japanese encephalitis virus premembrane and envelope genes. J. Virol. 72:4925-4930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ku, C. C., C. C. King, C. Y. Lin, H. C. Hsu, L. Y. Chen, Y. Y. Yueh, and G. J. Chang. 1994. Homologous and heterologous neutralization antibody responses after immunization with Japanese encephalitis vaccine among Taiwan children. J. Med. Virol. 44:122-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin, Y. L., L. K. Chen, C. L. Liao, C. T. Yeh, S. H. Ma, J. L. Chen, Y. L. Huang, S. S. Chen, and H. Y. Chiang. 1998. DNA immunization with Japanese encephalitis virus nonstructural protein NS1 elicits protective immunity in mice. J. Virol. 72:191-200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu, Z. L., S. Hennessy, B. L. Strom, T. F. Tsai, C. M. Wan, S. C. Tang, C. F. Xiang, W. B. Bilker, X. P. Pan, Y. J. Yao, Z. W. Xu, and S. B. Halstead. 1997. Short-term safety of live attenuated Japanese encephalitis vaccine (SA14-14-2): results of a randomized trial with 26,239 subjects. J. Infect. Dis. 176:1366-1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mason, P. W., J. M. Dalrymple, M. J. Fournier, and T. L. Mason. 1987. Expression of Japanese encephalitis virus antigens in Escherichia coli. Virology 158:361-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mason, P. W., S. Pincus, M. J. Fournier, T. L. Mason, R. E. Shope, and E. Paoletti. 1991. Japanese encephalitis virus-vaccinia recombinants produce particulate forms of the structural membrane proteins and induce high levels of protection against lethal JEV infection. Virology 180:294-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsuura, Y., M. Miyamoto, T. Sato, C. morita, and K. Yasui. 1989. Characterization of Japanese encephalitis virus envelope protein expressed by recombinant baculoviruses. Virology 173:674-682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCown, J., M. Cochran, R. Putnak, R. Feighny, J. Burrous, E. Henchal, and C. Hoke. 1990. Protection of mice against lethal Japanese encephalitis with a recombinant baculovirus vaccine. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 42:491-499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Monath, T. P., and F. X. Heinz. 1996. Flaviviruses, p. 961-1034. In B. N. Fields, D. M. Knipe, and P. M. Howley (ed.), Field's virology, 3rd ed. Lippincott-Raven Publishers, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 33.Mosmann, T. R., and R. L. Coffman. 1989. Heterogeneity of cytokine secretion patterns and functions of helper T cells. Adv. Immunol. 46:111-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Niwa, H., K. Yamamura, and J. Miyazaki. 1991. Efficient selection for high-expression transfectants with a novel eukaryotic vector. Gene 108:193-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nothdurft, H. D., T. Jelinek, A. Marschang, H. Maiwald, A. Kapaun, and T. Loscher. 1996. Adverse reactions to Japanese encephalitis vaccine in travellers. J. Infect. 32:119-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Phillpotts, R. J., K. Venugopal, and T. Brooks. 1996. Immunization with DNA polynucleotides protects mice against lethal challenge with St. Louis encephalitis virus. Arch. Virol. 141:743-749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pincus, S., P. W. Mason, E. Konishi, B. A. L. Fonseca, R. E. Shope, C. M. Rice, and E. Paoletti. 1992. Recombinant vaccinia virus producing the prM and E proteins of Yellow fever virus protects mice from lethal Yellow fever encephalitis. Virology 187:290-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Poland, J. D., C. B. Cropp, R. B. Craven, and T. P. Monath. 1990. Evaluation of the potency and safety of inactivated Japanese encephalitis vaccine in US inhabitants. J. Infect. Dis. 161:878-882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rice, C. M. 1996. Flaviviridae: the viruses and their replication, p. 931-959. In B. N. Fields, D. M. Knipe, and P. M. Howley (ed.). Field's virology, 3rd ed. Lippincott-Raven Publishers, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 40.Roman, M., E. Martin-Orozco, J. S. Goodman, M-D. Nguten, Y. Sato, A. Ronaghy, R. S. Kornbluth, D. D. Richman, D. A. Carson, and E. Raz. 1997. Immunostimulatory DNA sequences function as T helper-1-promoting adjuvants. Nat. Med. 3:849-854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rooney, J. F., C. Wohlenberg, K. J. Cremer, B. Moss, and A. L. Notkins. 1988. Immunization with a vaccinia virus recombinant expressing herpes simplex virus type 1 glycoprotein D: long-term protection and effect of revaccination. J. Virol. 62:1530-1749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sakaguchi, M., M. Yoshida, W. Kuroda, O. Harayama, Y. Matsunaga, and S. Inouye. 1997. Systemic immediate-type reactions to gelatin included in Japanese encephalitis vaccines. Vaccine 15:121-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sakaguchi, M., R. Tomiyoshi, T. Kuroiwa, K. Mihara, and T. Omura. 1992. Functions of signal and signal-anchor sequences are determined by the balance between the hydrophobic segment and the N-terminal charge. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:16-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sato, T., C. Tagamura, A. Yasuda, M. Miyamoto, K. Kamogawa, and K. Yasui. 1993. High-level expression of the Japanese encephalitis virus E protein by recombinant vaccinia virus and enhancement of its extracellular release by the NS3 gene product. Virology 192:483-490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schmaljohn, C., L. Vanderzanden, M. Bray, D. Custer, B. Meyer, D. Li, C. Rossi, D. Fuller, J. Fuller, J. Haynes, and J. Huggins. 1997. Naked DNA vaccines expressing the prM and E genes of Russian spring-summer encephalitis virus and central European encephalitis virus protect mice from homologous and heterologous challenge. J. Virol. 71:9563-9569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stubbs, A. C., K. S. Martin, C. Coeshott, S. V. Skaates, D. R. Kuritzkes, D. Bellgrau, A. Franzusoff, R. C. Duke, and C. C. Wilson. 2001. Whole recombinant yeast vaccine activates dendritic cells and elicits protective cell-mediated immunity. Nat. Med. 7:625-629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sumiyoshi, H., C. Mori, I. Fuke, K. Morita, S. Kuhara, J. Kondou, Y. Kikuchi, H. Nagamatu, and A. Igarashi. 1987. Complete nucleotide sequence of the Japanese encephalitis virus genome RNA. Virology 161:497-510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Takebe, Y., M. Seiki, J. Fujisawa, P. Hoy, K. Yokota, K. Arai, M. Yoshida, and N. Arai. 1988. SRα promoter: an efficient and versatile mammalian cDNA expression system composed of the simian virus 40 early promoter and the R-U5 segment of human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 long terminal repeat. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8:466-472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ueba, N., T. Kimura, S. Nakajima, T. Kurimura, and T. Kitaura. 1978. Field experiments on live attenuated Japanese encephalitis virus vaccine for swine. Biken J. 21:95-103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ulmer, J. B., J. J. Donnely, S. E. Parker, G. H. Rhodes, P. L. Felgner, V. J. Dwarki, S. H. Gromkowski, R. R. Deck, C. M. DeWitt, A. Friedman, L. A. Hawe, K. R. Leander, D. Martinez, H. C. Perry, J. W. Shiver, D. L. Montgomery, and M. A. Liu. 1993. Heterologous protection against influenza by injection of DNA encoding a viral protein. Science 159:1745-1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wengler, G., and G. Wengler. 1989. An analysis of the antibody response against West Nile virus E protein purified by SDS-PAGE indicates that this protein does not contain sequential epitopes for efficient induction of neutralizing antibodies. J. Gen. Virol. 70:987-992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xin, Y. Y., Z. G. Ming, G. Y. Peng, A. Jian, and L. H. Min. 1988. Safety of a live-attenuated Japanese encephalitis virus vaccine (SA14-14-2) for children. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 39:214-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yasuda, A., J. Kimura-Kuroda, M. Ogimoto, M. Miyamoto, T. Sata, T. Sato, C. Takamura, A. Kojima, and K. Yasui. 1990. Induction of protective immunity in animals vaccinated with recombinant vaccinia viruses that express preM and E glycoproteins of Japanese encephalitis virus. J. Virol. 64:2788-2795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.You, Z., X. Huang, J. Hester, H. C. Toh, and S.-Y. Chen. 2001. Targeting dendritic cells to enhance DNA vaccine potency. Cancer Res. 61:3704-3711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]