Abstract

We have previously shown that virions with nef deleted can be restored to wild-type infectivity by treatment to induce natural endogenous reverse transcription (NERT). Since Nef and cyclophilin A (CyPA) appear to act in similar ways on postentry events, we determined whether NERT treatment would restore infectivity to virions depleted of CyPA. Our results show that the infectivity of virions depleted of CyPA by treatment with cyclosporine A could be restored by NERT treatment, while mutants in the CyPA binding loop of capsid could only be partially restored. These results suggest that CyPA is involved in some aspect of the uncoating process.

Human cyclophilin A (CyPA) is required for full infectivity of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) virions (6, 11, 26). It is incorporated into virions via specific interactions with the capsid (CA) region of the Gag precursor (9, 11) and is the target of the immunosuppressive drug cyclosporine A (CsA) (6, 8, 10, 26). CyPA appears to be involved in both entry and postentry events during viral replication (25). It facilitates entry through interactions between the incorporated CyPA and CD147 on the cell surface (23). CyPA has also been postulated to facilitate uncoating (20). Originally, this activity was thought to be a consequence of the cis-trans prolyl isomerase activity of CyPA (15, 16). Specifically, CyPA can bind to CA (14) and modify the folding of CA to potentially influence the structure of the mature core (1, 5). However, more recent studies have shown that the isomerase activity of CyPA is not required for enhancement of infectivity (24). In addition, CyPA is not required for particle maturation, and its absence does not destabilize the mature core (28). Therefore, it appears that CyPA is able to facilitate uncoating without directly affecting core stability.

There are intriguing similarities between the actions of CyPA and HIV-1 Nef on postentry effects. Full infectivity of virions with nef or CyPA depleted can be restored by trans-complementation in the viral producer cells but not the target cells (4, 11, 22). This suggests that both proteins must be present during virus assembly to have an effect. Both proteins are present in viral particles and are associated with the viral core (11, 19). In the absence of Nef or CyPA, infectivity can be restored by pseudotyping with the vesicular stomatitis virus G (VSV-G) envelope glycoprotein but not murine leukemia virus envelope glycoprotein (2). These similarities suggest that Nef and CyPA may be acting by similar mechanisms to enhance infectivity. However, it has been shown that virions with nef deleted remain partially sensitive to the effects of CsA (3). In addition, virions with mutations in the CyPA-binding loop of Gag, which are already reduced in infectivity, have even lower infectivity when the nef gene is also deleted (3). These observations leave some doubt as to the actual interdependence between Nef and CyPA in the enhancement of infectivity.

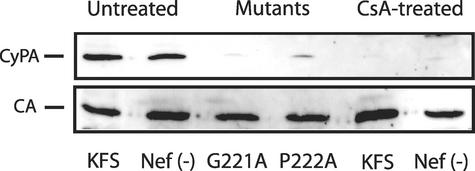

We have previously shown that treatment of virions with nef deleted by natural endogenous reverse transcription (NERT) restores infectivity to wild-type (WT) levels (18). We speculate that NERT relieves the need for Nef because NERT treatment results in partial disassembly of the core particle and breakage of the core envelope linkage (CEL), which is an attachment of the small end of the core to the envelope (17, 29). To determine if NERT treatment would have a similar effect on virions which are depleted of CyPA, we produced virions by transfection with the plasmid pNL4-3KFS (12) or a version of the same plasmid with nef deleted, pNL4-3KFSΔNEF [denoted Nef(−)] (gift of Judith Levin, National Institutes of Health [NIH]) in the presence of 10 μM CsA. In these clones the envelope glycoproteins were deleted by linker insertion and were complemented by either HIV-1 envelope plasmid pIIIenv or pseudotyped with VSV-G envelope glycoprotein as previously described (18). As another means to deplete virions of CyPA, we also made two independent point mutations, G221A and P222A, in CA of pNL4-3KFS which have been previously shown to inhibit CyPA incorporation into virions (6, 11). Western blotting of the disrupted virions confirmed the reduction of CyPA in both CsA-treated virions and the CA mutants (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

CyPA is not present in either CsA-treated virions or CA mutants G221A and P222A. Virions were produced by cotransfection of 293 cells with HIV-1NL4-3KFS plasmid DNA and HIV-1 Env plasmid pIIIenv. Virions were purified by centrifugation through a 20% sucrose cushion and 25 ng was lysed and separated on a sodium dodecyl sulfate-4-to-20% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gel and analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies against human CyPA and HIV-1 CA.

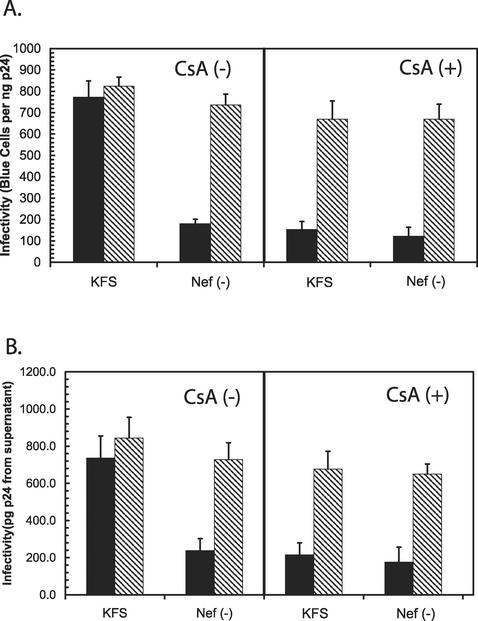

To determine if NERT could restore infectivity to virions depleted of CyPA, we treated viral particles produced in the presence of CsA with NERT cocktail as previously described (18). For comparison, we also included virions with nef deleted and also virions with nef deleted that had been treated with CsA. The results are summarized in Fig. 2. The virions depleted of nef and CyPA showed a similar fourfold reduction in infectivity as determined by multinuclear activation of a galactosidase indicator (MAGI) assay (Fig. 2A) and by measurement of p24 antigen from the supernatants of infected cells (Fig. 2B). After treatment by NERT, the infectivity of all of the virions was substantially increased to near WT levels. We consistently observed that virions depleted of CyPA, whether alone or in combination with nef deletion, showed lower levels of infectivity, but the difference was not statistically significant. This difference may be a reflection of the fact that CyPA has an influence on both entry and attachment (25), and NERT treatment would not be expected to rescue the defects involving attachment.

FIG. 2.

NERT treatment can restore the infectivity of virions produced in the presence of CsA. KFS and Nef(−) virions were produced in the presence [CsA (+)] and absence [CsA (-)] of 10 μM CsA. (A) Each virion preparation was then directly tested for infectivity (solid bars) or treated with NERT cocktail for 4 h (hatched bars) and then tested for infectivity by the MAGI cell assay. (B) In addition, the p24 antigen content from the supernatants of the MAGI assays was also determined.

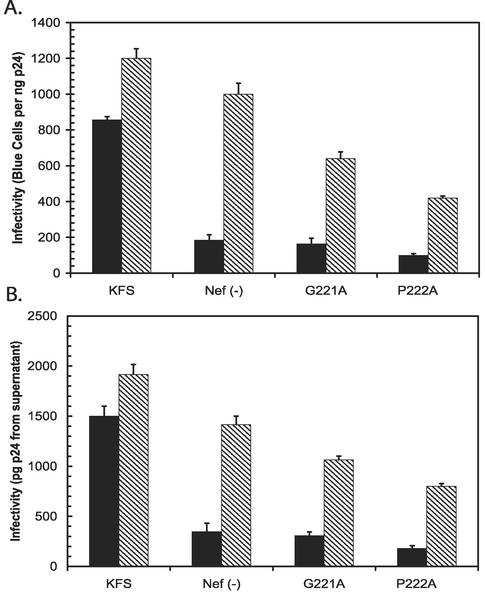

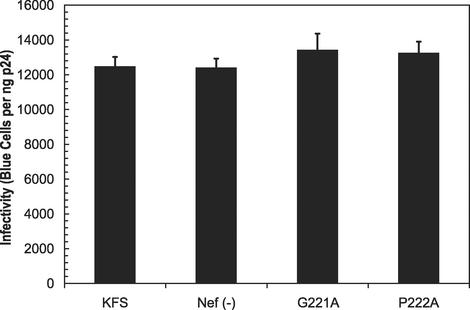

To further determine the effects of NERT treatment on virions depleted of CyPA, we tested the CA mutants G221A and P222A, which disrupt CyPA binding (11). For comparison, we included virions with nef deleted and KFS virions. The results are summarized in Fig. 3. Both CA mutants reduced infectivity about fourfold, which was similar to the reduction seen with CsA-treated virions. In this case, NERT treatment was only able to partially restore the infectivity of the mutants (Fig. 3). In addition, the ability to restore infectivity was different for G221A, about 56%, and P222A, about 36%, in relation to the NERT-treated KFS virions. This was true even though the effects of NERT treatment on both the KFS virions and the virions with nef deleted were more pronounced (note that the virions with nef deleted were restored to approximately 135%). Measurement of infectivity by determining p24 content in the supernatant of infected cells revealed similar results (Fig. 3B). Since NERT treatment was able to restore CsA-treated virions closer to WT levels, we believe that the differential effects on the CA mutants could be due to the unavoidable changes in the core particle, which is predominantly composed of CA protein. The mutations could alter CA-CA interactions to change core stability or otherwise alter the ability of cores to disassemble independently of CyPA incorporation.

FIG. 3.

The infectivity of CA mutants G221A and P222A could be partially restored by NERT treatment. Virion preparations from KFS, Nef(−), and CA mutants G221A and P222A were purified by centrifugation through a 20% sucrose cushion. One nanogram of each preparation was either directly tested for infectivity (solid bars) or treated with NERT cocktail (hatched bars) for 4 h. Note that the enhancement of infectivity of the KFS and Nef(−) preparations was greater than that of untreated KFS.

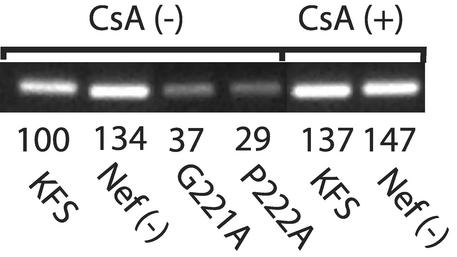

To investigate whether these changes could affect the NERT process, we monitored the amount of strong-stop DNA produced in KFS and Nef(−) virions after reaction in NERT cocktail for 4 h as previously described (18). For comparison we also tested the same virions produced in the presence of 10 μM CsA and the capsid mutants G221A and P222A. The results are shown in Fig. 4. The amount of strong-stop DNA produced in the two capsid mutants G221A and P222A was 37 and 29% of WT, respectively, as determined by real-time PCR in the presence of SYBR green as a label and analyzed using the Bio-Rad I-cycler. The amount of reverse transcriptase in each preparation was equivalent, as determined by Western blotting of the individual NERT reaction mixtures (data not shown). These data show that the capsid mutations had a direct effect on the efficiency of the NERT reaction. This could reflect either an inability of the cores to efficiently disassemble or a direct effect on the process of reverse transcription. The level of proviral DNA was roughly proportional to the infectivity enhancement (Fig. 3) and could explain why NERT treatment only partially restored the infectivity of the CA mutants.

FIG. 4.

The relative efficiency of NERT was determined for KFS, Nef(−) virions in the presence and absence of 10 μM CsA and for the CA mutants G221A and P222A. For this comparison, PCR was done on virions after a 4-h NERT treatment, using primers to detect minus-strand strong-stop DNA. The numbers beneath each band show results of real-time PCR quantitation expressed as %KFS.

To determine if the CA mutants G221A and P222A could be rescued by pseudotyping with the VSV-G envelope, we created KFS virions, virions with nef deleted, and G221A and P222A CA mutants that were all pseudotyped with the VSV-G envelope glycoprotein (pHCMV-G; kind gift of Jane Burns, University of California, San Diego). Each of the virion preparations was normalized for p24 content and then tested for infectivity using the MAGI assay. The results are summarized in Fig. 5. All of the defective virions were restored to WT levels of infectivity when pseudotyped with the VSV-G envelope protein, which targets virions to entry by the endocytic pathway. Mutants in the CyPA-binding region have been previously reported to be unable to be rescued by VSV-G pseudotyping (2). Therefore, we wished to confirm the phenotype of the progeny virions after infection. We collected virions from the tissue culture supernatants of the MAGI assays shown in Fig. 5 and performed Western blotting for the presence of CyPA. The virions harvested from infection by the G221A and P222A mutants had no detectable CyPA (data not shown) and were about 15-fold higher in infectivity (Fig. 5). These observations confirm that the virions were VSV-G pseudotyped (because of the increase in infectivity) and were unable to incorporate CyPA. We were unable to determine why the virions were able to be rescued by VSV-G pseudotyping in our hands; however, small differences in the clones or the procedures used to produce virions could account for the discrepancy.

FIG. 5.

The infectivity of the CA mutants G221A and P222A could be restored by pseudotyping virions with VSV-G envelope protein. Preparations of virions pseudotyped with the VSV-G envelope were produced by cotransfection of 293 cells with HIV-1NL4-3KFS plasmid DNA and pHCMV-G plasmid DNA. KFS viral DNA, which contained a deletion of nef or mutations in capsid residues G221A or P222A, was also tested. In each case, the level of infectivity was the same as that of KFS without mutations (WT).

It is interesting that while NERT treatment was unable to fully rescue the two CA mutants, G221A and P222A, VSV-G pseudotyping was able to fully rescue both mutants. This may be a reflection of the differential effects of the mutants on core stability when artificially disrupted in each environment. In the case of VSV-G-pseudotyped particles, core disassembly may occur through a pH-dependent mechanism, while NERT treatment appears to cause core disassembly as a consequence of the stimulation of reverse transcription or the influx of deoxynucleoside triphosphates.

Our results show that virions depleted of CyPA can be restored in infectivity by NERT treatment in a manner similar to the restoration of virions with nef deleted (18). This is consistent with the observation that VSV-G pseudotyping can restore both virions depleted of CyPA and virions depleted of nef (2). Both treatments induce disassembly through a pathway different than normal disassembly. These observations support the idea that both Nef and CyPA are involved in the disassembly of the core particle.

Since neither protein appears to directly affect core stability, it seems likely that they participate in the uncoating process in some other manner. Neither CyPA nor Nef are absolutely required for virion infectivity (virions with nef deleted and depleted of CyPA are infectious [4, 6]). Therefore, the role of both of these factors appears to be to enhance infectivity. One possibility is that both proteins are involved in the detachment of the core from the viral envelope. NERT treatment has been shown to disrupt a structure known as the CEL, which appears to be a physical attachment of the core to the viral envelope (17, 29). Nef can be anchored in the viral envelope via its N-terminal myristoylation (27), and CyPA is known to interact directly with CA (11, 21, 26). This could provide the two ends of a link between the core and envelope.

It has been shown that for HIV-2, simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV), and some group O isolates there is no requirement for CyPA for full infectivity (6) and that CyPA-independent replication can be conferred to an HIV-1 isolate containing a small portion of SIV Gag (13). In these cases, it is possible that the changes in CA or the differences in the sequence of the Nef from these viruses could compensate for the need for CyPA. For example, the changes could allow a linkage of Nef either directly to CA or through a different intermediate or intermediates, bypassing the need for CyPA.

In other cases, virions with mutations in CA that are unable to incorporate CyPA or virions produced in the presence of CsA can ultimately replicate in WT Jurkats cells (3) with altered kinetics. Also, HIV-1 virions replicate with delayed kinetics in Jurkat cells that are CyPA null (7, 25). In these cases there may be no CEL formed, but the requirement for a CEL may not be absolute. One possible explanation for the role of a CEL could be that it keeps the core anchored near the cell membrane until deoxynucleoside triphosphate concentrations are optimal to stimulate reverse transcription. At that time, the core would disassemble and replication could proceed. Under conditions where a CEL cannot form, it may still be possible for the core to ultimately disassemble, but possibly in a subcellular location that is less optimal for efficient replication.

Of course many alternatives exist for the function of CyPA and Nef, including the possibility of a more-direct effect on the process of reverse transcription. Our results suggest that CyPA and Nef may act on similar aspects of the uncoating process, but more investigation will be necessary to determine how or if these two proteins function in that role.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants G12-RR03034 and S06GM08248.

We are grateful to E. Freed and J. Levin (NIH, Bethesda, Md.) for supplying the KFS and KFSΔNef plasmids.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agresta, B. E., and C. A. Carter. 1997. Cyclophilin A-induced alterations of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 CA protein in vitro. J. Virol. 71:6921-6927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aiken, C. 1997. Pseudotyping human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) by the glycoprotein of vesicular stomatitis virus targets HIV-1 entry to an endocytic pathway and suppresses both the requirement for Nef and the sensitivity to cyclosporin A. J. Virol. 71:5871-5877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aiken, C. 1998. Mechanistic independence of Nef and cyclophilin A enhancement of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infectivity. Virology 248:139-147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aiken, C., and D. Trono. 1995. Nef stimulates human immunodeficiency virus type 1 proviral DNA synthesis. J. Virol. 69:5048-5056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bosco, D. A., E. Z. Eisenmesser, S. Pochapsky, W. I. Sundquist, and D. Kern. 2002. Catalysis of cis/trans isomerization in native HIV-1 capsid by human cyclophilin A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:5247-5252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braaten, D., E. K. Franke, and J. Luban. 1996. Cyclophilin A is required for the replication of group M human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) and simian immunodeficiency virus SIVCPZGAB but not group O HIV-1 or other primate immunodeficiency viruses. J. Virol. 70:4220-4227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braaten, D., and J. Luban. 2001. Cyclophilin A regulates HIV-1 infectivity, as demonstrated by gene targeting in human T cells. EMBO J. 20:1300-1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bukovsky, A. A., A. Weimann, M. A. Accola, and H. G. Gottlinger. 1997. Transfer of the HIV-1 cyclophilin-binding site to simian immunodeficiency virus from Macaca mulatta can confer both cyclosporin sensitivity and cyclosporin dependence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:10943-10948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colgan, J., H. E. Yuan, E. K. Franke, and J. Luban. 1996. Binding of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag polyprotein to cyclophilin A is mediated by the central region of capsid and requires Gag dimerization. J. Virol. 70:4299-4310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Franke, E. K., and J. Luban. 1996. Inhibition of HIV-1 replication by cyclosporine A or related compounds correlates with the ability to disrupt the Gag-cyclophilin A interaction. Virology 222:279-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franke, E. K., H. E. Yuan, and J. Luban. 1994. Specific incorporation of cyclophilin A into HIV-1 virions. Nature 372:359-362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Freed, E. O., E. L. Delwart, G. L. Buchschacher, Jr., and A. T. Panganiban. 1992. A mutation in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transmembrane glycoprotein gp41 dominantly interferes with fusion and infectivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:70-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fujita, M., A. Yoshida, M. Miyaura, A. Sakurai, H. Akari, A. H. Koyama, and A. Adachi. 2001. Cyclophilin A-independent replication of a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolate carrying a small portion of the simian immunodeficiency virus SIVMAC gag capsid region. J. Virol. 75:10527-10531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gamble, T. R., F. F. Vajdos, S. Yoo, D. K. Worthylake, M. Houseweart, W. I. Sundquist, and C. P. Hill. 1996. Crystal structure of human cyclophilin A bound to the amino-terminal domain of HIV-1 capsid. Cell 87:1285-1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gething, M. J., and J. Sambrook. 1992. Protein folding in the cell. Nature 355:33-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Handschumacher, R. E., M. W. Harding, J. Rice, R. J. Drugge, and D. W. Speicher. 1984. Cyclophilin: a specific cytosolic binding protein for cyclosporin A. Science 226:544-547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoglund, S., L. G. Ofverstedt, A. Nilsson, P. Lundquist, H. Gelderblom, M. Ozel, and U. Skoglund. 1992. Spatial visualization of the maturing HIV-1 core and its linkage to the envelope. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 8:1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khan, M., M. Garcia-Barrio, and M. D. Powell. 2001. Restoration of wild-type infectivity to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 strains lacking nef by intravirion reverse transcription. J. Virol. 75:12081-12087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kotov, A., J. Zhou, P. Flicker, and C. Aiken. 1999. Association of Nef with the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 core. J. Virol. 73:8824-8830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luban, J. 1996. Absconding with the chaperone: essential cyclophilin-Gag interaction in HIV-1 virions. Cell 87:1157-1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luban, J., K. L. Bossolt, E. K. Franke, G. V. Kalpana, and S. P. Goff. 1993. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag protein binds to cyclophilins A and B. Cell 73:1067-1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller, M. D., M. T. Warmerdam, I. Gaston, W. C. Greene, and M. B. Feinberg. 1994. The human immunodeficiency virus-1 nef gene product: a positive factor for viral infection and replication in primary lymphocytes and macrophages. J. Exp. Med. 179:101-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pushkarsky, T., G. Zybarth, L. Dubrovsky, V. Yurchenko, H. Tang, H. Guo, B. Toole, B. Sherry, and M. Bukrinsky. 2001. CD147 facilitates HIV-1 infection by interacting with virus-associated cyclophilin A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:6360-6365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saphire, A. C., M. D. Bobardt, and P. A. Gallay. 2002. trans-complementation rescue of cyclophilin A-deficient viruses reveals that the requirement for cyclophilin A in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication is independent of its isomerase activity. J. Virol. 76:2255-2262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saphire, A. C., M. D. Bobardt, and P. A. Gallay. 2002. Cyclophilin A plays distinct roles in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 entry and postentry events, as revealed by spinoculation. J. Virol. 76:4671-4677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thali, M., A. Bukovsky, E. Kondo, B. Rosenwirth, C. T. Walsh, J. Sodroski, and H. G. Gottlinger. 1994. Functional association of cyclophilin A with HIV-1 virions. Nature 372:363-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Welker, R., M. Harris, B. Cardel, and H. G. Krausslich. 1998. Virion incorporation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef is mediated by a bipartite membrane-targeting signal: analysis of its role in enhancement of viral infectivity. J. Virol. 72:8833-8840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wiegers, K., G. Rutter, U. Schubert, M. Grattinger, and H. G. Krausslich. 1999. Cyclophilin A incorporation is not required for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 particle maturation and does not destabilize the mature capsid. Virology 257:261-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang, H., G. Dornadula, J. Orenstein, and R. J. Pomerantz. 2000. Morphologic changes in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 virions secondary to intravirion reverse transcription: evidence indicating that reverse transcription may not take place within the intact viral core. J. Hum. Virol. 3:165-172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]