Abstract

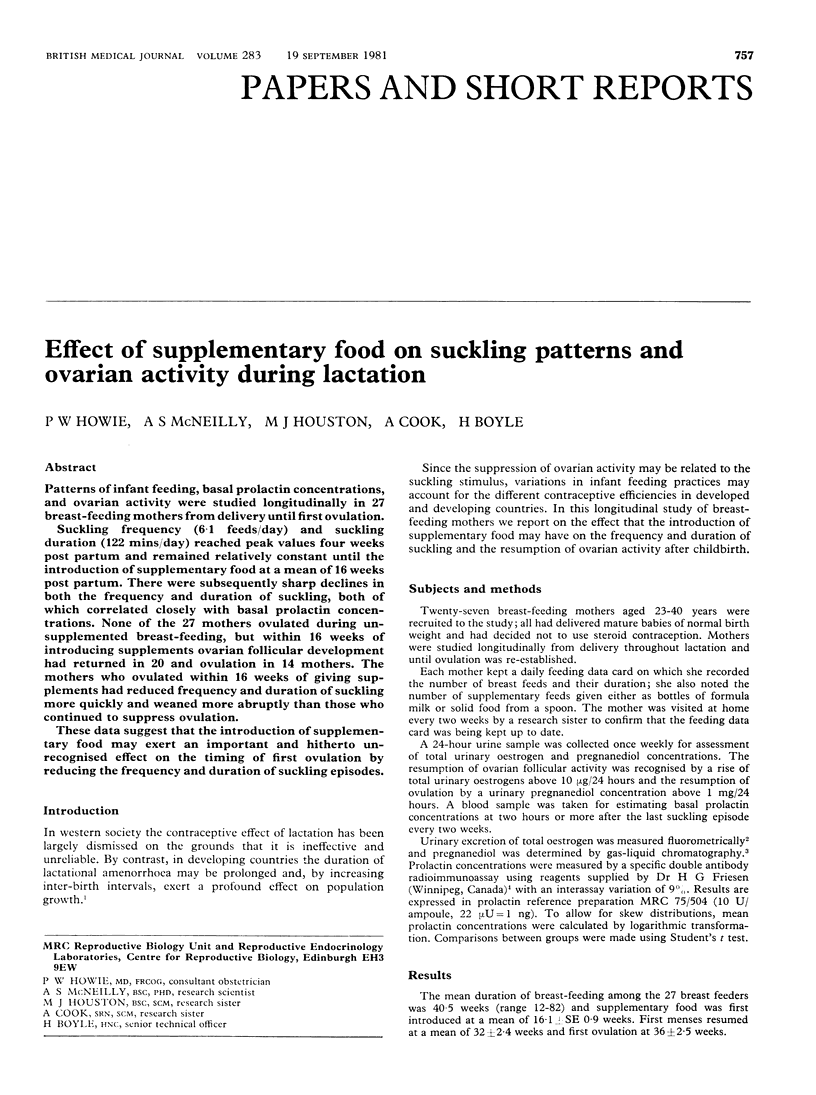

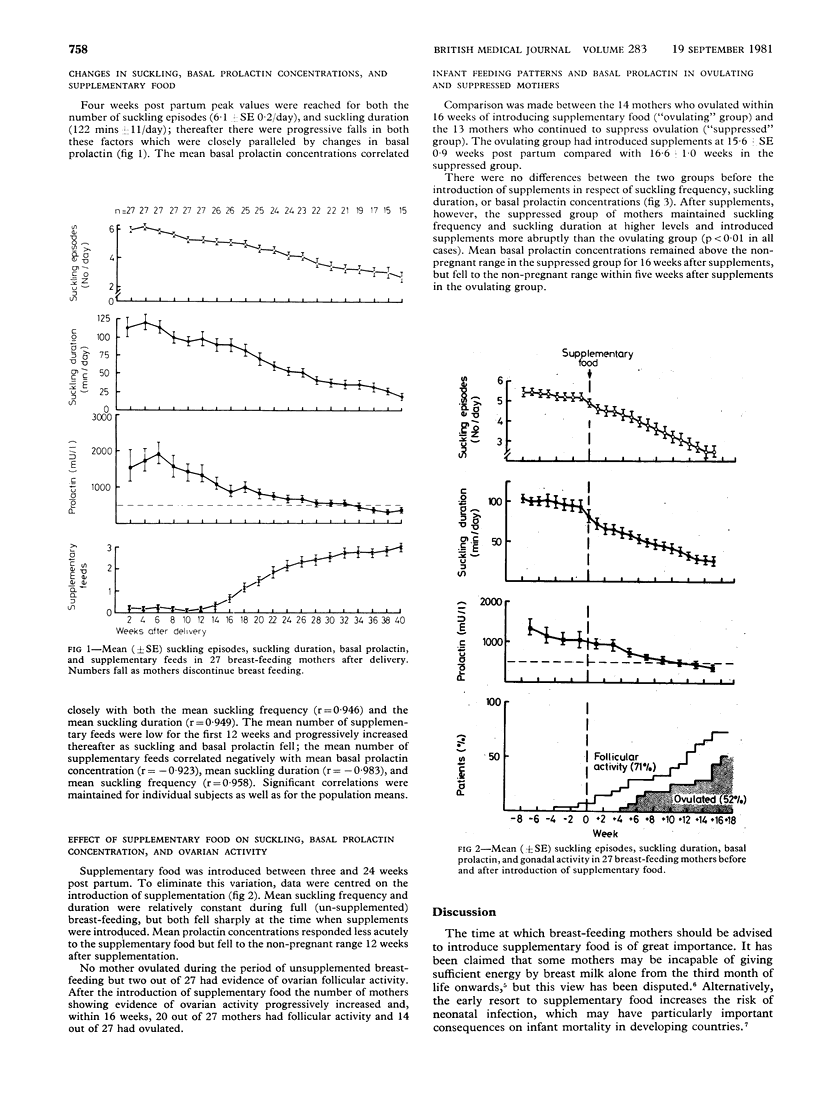

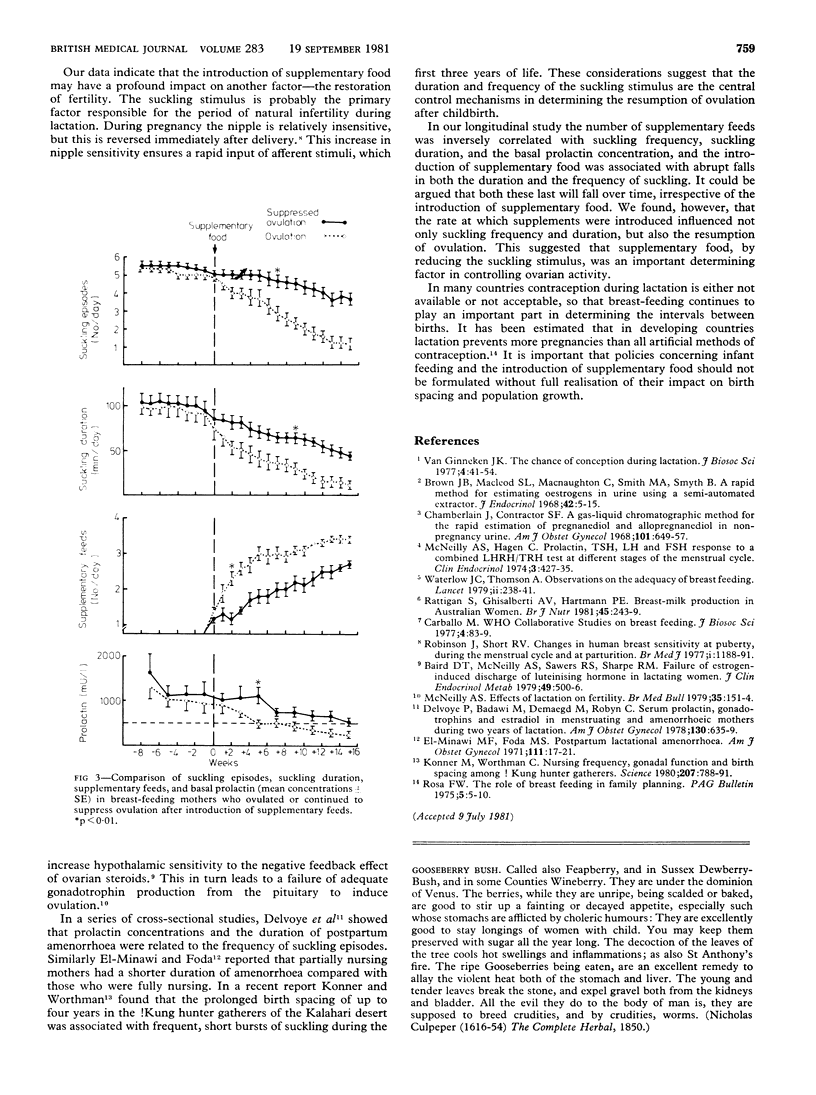

Patterns of infant feeding, basal prolactin concentrations, and ovarian activity were studied longitudinally in 27 breast-feeding mothers from delivery until first ovulation. Suckling frequency (6.1 feeds/day) and suckling duration (122 mins/day) reached peak values four weeks post partum and remained relatively constant until the introduction of supplementary food at a mean of 16 weeks post partum. There were subsequently sharp declines in both the frequency and duration of suckling, both of which correlated closely with basal prolactin concentrations. None of the 27 mothers ovulated during unsupplemented breast-feeding, but within 16 weeks of introducing supplements ovarian follicular development had returned in 20 and ovulation in 14 mothers. The mothers who ovulated within 16 weeks of giving supplements had reduced frequency and duration of suckling more quickly and weaned more abruptly than those who continued to suppress ovulation. These data suggest that the introduction of supplementary food may exert an important and hitherto unrecognised effect on the timing of first ovulation by reducing the frequency and duration of suckling episodes.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Baird D. T., McNeilly A. S., Sawers R. S., Sharpe R. M. Failure of estrogen-induced discharge of luteinizing hormone in lactating women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1979 Oct;49(4):500–506. doi: 10.1210/jcem-49-4-500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delvoye P., Demaegd M., Uwayitu-Nyampeta, Robyn C. Serum prolactin, gonadotropins, and estradiol in menstruating and amenorrheic mothers during two years' lactation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1978 Mar 15;130(6):635–639. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(78)90319-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konner M., Worthman C. Nursing frequency, gonadal function, and birth spacing among !Kung hunter-gatherers. Science. 1980 Feb 15;207(4432):788–791. doi: 10.1126/science.7352291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeilly A. S. Effects of lactation on fertility. Br Med Bull. 1979 May;35(2):151–154. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a071562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeilly A. S., Hagen C. Prolactin, TSH, LH and FSH responses to a combined LHRH-TRH test at different stages of the menstrual cycle. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1974 Oct;3(4):427–435. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1974.tb02813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rattigan S., Ghisalberti A. V., Hartmann P. E. Breast-milk production in Australian women. Br J Nutr. 1981 Mar;45(2):243–249. doi: 10.1079/bjn19810100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson J. E., Short R. V. Changes in breast sensitivity at puberty, during the menstrual cycle, and at parturition. Br Med J. 1977 May 7;1(6070):1188–1191. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6070.1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosa F. W. Breast-feeding in family planning. Pag Bull. 1975 Sep;5(3):5–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterlow J. C., Thomson A. M. Observations on the adequacy of breast-feeding. Lancet. 1979 Aug 4;2(8136):238–242. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(79)90248-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- el-Minawi M. F., Foda M. S. Postpartum lactation amenorrhea: endometrial pattern and reproductive ability. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1971 Sep;111(1):17–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]