Abstract

The latent transforming growth factor-β–binding protein-1 (LTBP-1) belongs to a family of extracellular glycoproteins that includes three additional isoforms (LTBP-2, -3, and -4) and the matrix proteins fibrillin-1 and -2. Originally described as a TGF-β–masking protein, LTBP-1 is involved both in the sequestration of latent TGF-β in the extracellular matrix and the regulation of its activation in the extracellular environment. Whereas the expression of LTBP-1 has been analyzed in normal and malignant cells and rodent and human tissues, little is known about LTBP-1 in embryonic development. To address this question, we used murine embryonic stem (ES) cells to analyze the appearance and role of LTBP-1 during ES cell differentiation. In vitro, ES cells aggregate to form embryoid bodies (EBs), which differentiate into multiple cell lineages. We analyzed LTBP-1 gene expression and LTBP-1 fiber appearance with respect to the emergence and distribution of cell types in differentiating EBs. LTBP-1 expression increased during the first 12 d in culture, appeared to remain constant between d 12 and 24, and declined thereafter. By immunostaining, fibrillar LTBP-1 was observed in those regions of the culture containing endothelial, smooth muscle, and epithelial cells. We found that inclusion of a polyclonal antibody to LTBP-1 during EB differentiation suppressed the expression of the endothelial specific genes ICAM-2 and von Willebrand factor and delayed the organization of differentiated endothelial cells into cord-like structures within the growing EBs. The same effect was observed when cultures were treated with either antibodies to TGF-β or the latency associated peptide, which neutralize TGF-β. Conversely, the organization of endothelial cells was enhanced by incubation with TGF-β1. These results suggest that during differentiation of ES cells LTBP-1 facilitates endothelial cell organization via a TGF-β–dependent mechanism.

INTRODUCTION

The latent transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β)–binding protein (LTBP)-1 was isolated as a component of the latent TGF-β complex released from platelets (Miyazono et al., 1988). LTBP-1 consists of multiple epidermal growth factor-like domains, many of which contain a calcium-binding motif, and multiple domains with eight cysteine residues. LTBP-1 is a member of a family of molecules, LTBP-1–4, with closely related sequences and molecular masses of ∼140–220 kDa (Tsuji et al., 1990; Moren et al., 1994; Yin et al., 1995; Giltay et al., 1997). The LTBPs are structurally similar to the microfibrillar proteins fibrillins 1 and 2, all of which contain multiple epidermal growth factor-like sequences and eight-cysteine domains. LTBP-1, -3, and -4 bind covalently to TGF-β (Gleizes et al., 1996; Munger et al., 1997) via disulfide bonds between cysteine residues in the third eight-cysteine repeat of LTBP-1 and cysteine 33 in the TGF-β1 propeptide. Latency of the TGF-β complex is conferred by the continued noncovalent association of the TGF-β propeptide dimer, also called the latency-associated peptide (LAP), with the active cytokine dimer even after secretion. This complex of TGF-β plus propeptide is called the small latent complex. The complex of TGF-β, propeptide dimer, and LTBP-1 is called the large latent complex (LLC). Immunohistochemical and immunomicroscopical studies have demonstrated the presence of fibrillar LTBPs colocalized in the extracellular matrix (ECM) with collagen, fibronectin, and fibrillin (Dallas et al., 1995, 2000; Taipale et al., 1996). In adult rat and human tissues LTBP-1 mRNA was detected in heart, lung, spleen, kidney, stomach, placenta, prostate, and testis (Tsuji et al., 1990; Olofsson et al., 1995). In addition, in 8.5- to 13.5-d-old mouse embryos, LTBP-1 is localized in the ECM of mesenchymal cells and in the basement membranes in regions of epithelial–mesenchymal interaction and tissue remodeling (Nakajima et al., 1999).

The function of LTBP-1 in vivo is unclear. The similarities and colocalization of the LTBPs and the fibrillins suggested a structural role for LTBP-1 in the ECM. In vitro evidence for such a role was provided by Dallas et al. (1995), who observed that a specific polyclonal antibody, Ab39, to LTBP-1 blocked the appearance of mineralized nodules in cultures of rat calvarial cells. The inhibition of mineralization was also observed when antisense oligonucleotides to LTBP-1 were added to the culture, but antibodies to TGF-β did not block nodule formation. This implied a direct, presumably structural, role for LTBP-1 in calvarial cell differentiation independently of TGF-β. Alternatively, the association of LTBP-1 with latent TGF-β indicated that LTBP-1 might participate in the conversion of latent to active TGF-β. Newly synthesized TGF-β is released from most cells as the LLC (Miller et al., 1992; Bailly et al., 1997; Gleizes et al., 1997; Munger et al., 1997). How TGF-β is released from the LLC is not clear. In cocultures of endothelial and smooth muscle cells or thioglycolate-elicited, lipopolysaccharide-stimulated macrophages, the formation of active TGF-β is blocked by Ab39. It has been proposed that LTBP-1 targets the LLC to the ECM, where tissue transglutaminase cross-links the latent complex to the ECM via LTBP-1 (Nunes et al., 1997). It is possible that Ab39 interferes with this step and thereby prevents the activation of latent TGF-β. A further example of the interrelationship of LTBP and TGF-β derives from the work of Nakajima et al. (1997), which demonstrated that LTBP-1 is required for the development of the heart. They showed that Ab39 blocked the endothelial–mesenchymal transition required for endocardial cushion formation in embryonic mouse heart cultures. Antibody inhibition was abrogated by the coadministration of TGF-β1 or TGF-β2 but not by TGF-β3. This effect is consistent with the ability of anti-TGF-β1, but not anti-TGF-β3, neutralizing antibodies to block the endothelial–mesenchymal transition. Thus, in this system LTBP-1 appears to be important for the generation of TGF-β in a temporal or spatial manner.

In an attempt to develop an additional in vitro assay for LTBP-1 during development, we have examined LTBP-1 distribution in cultures of differentiating mouse embryonic stem (ES) cells. When ES cells are cultured in vitro, they retain indefinitely their capacity to generate cells of all lineages, including the germ line, when introduced in the host blastocysts. If ES cells are depleted of feeder cells and leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF), cellular aggregates or EBs are formed by culturing cells on nonadhesive substrates, in hanging drops, or in methylcellulose (Keller, 1995; O'Shea, 1999). When transferred to an adhesive substratum, the EBs attach, grow, and differentiate into multiple cell lineages that radiate out from each EB. Thus, ES cells represent an in vitro model to analyze the early events in development and lineage specification (O'Shea, 1999). The ES system has been successfully used to study hematopoietic (Keller et al., 1993), cardiomyocyte (Robbins et al., 1990), skeletal muscle (Rohwedel et al., 1994), endothelial (Vittet et al., 1996; Hirashima et al., 1999), epithelial (Bagutti et al., 1996), and neuronal differentiation (Bain et al., 1995; Fraichard et al., 1995; Angelov et al., 1998).

Here we report that during in vitro EB differentiation extracellular fibers containing LTBP-1 colocalize with specific differentiating cell lineages, including endothelium. Addition of Ab39 to cultures of differentiating EBs interferes with the maturation and formation of a network of cord-like structures normally formed by differentiated endothelial cells. A similar phenotype is elicited either by recombinant LAP, which confers latency to active TGF-β, or by anti-TGF-β immunoglobulin (Ig) G. Conversely, the degree of endothelial cord formation was enhanced by the addition of free TGF-β. These data suggest that, during in vitro ES cell differentiation, LTBP-1 regulates endothelial cell development and differentiation by modulating TGF-β formation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

ES Cell Culture and Differentiation

Both W4 mouse ES stem cells, derived from the inner mass of preimplanted blastocysts of 129 SvEv strain mice, and embryonic mouse fibroblast cells (EMFI) were kindly provided by Dr. A. Joyner and established as described by Su et al. (1999); Auerbach, Dunmore, Fairchild-Huntress, Fang, Auerbach, Huszar, and Joyner (unpublished data); Kuroda et al. (2000); and Li Song and Joyner (2000). W4 ES cells were maintained in an undifferentiated state by culture on freshly prepared layers of EMFI pretreated with mitomycin C (10 μg/ml; Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Undifferentiated ES cells were cultured in high-glucose DMEM (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY), 15% fetal bovine serum (Gemini Bio-Products. Calabasas, CA), 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids (Life Technologies), 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Life Technologies), 10−4 M β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma), 2 mM l-glutamine (Life Technologies), penicillin-streptomycin (50 μg/ml each; Life Technologies), and 1000 U/ml LIF (Life Technologies). Cells were split 1:6 every 2 d, and the medium was changed every day.

For in vitro differentiation experiments, the same medium was used except that LIF was omitted and the fetal bovine serum concentration was increased to 20% (EB medium). The hanging drop procedure was followed (Keller, 1995). ES cells were removed from feeders as follows: ES cells grown to confluence on EMFI were dispersed using trypsin (0.05%) for 10 min and centrifuged at 300 × g for 3 min. The pellet was resuspended in 10 ml of ES medium, and the ES plus EMFI cell suspension was seeded onto a tissue culture dish for 30 min at 37°C. During this time, the EMFI attached to the bottom of the dish, whereas the ES cells remained in suspension. This step was repeated twice. The ES cell suspension was centrifuged at 300 × g for 3 min, and the pellet was resuspended in a suitable volume of EB medium for counting. Thirty-microliter drops, containing 400 cells, were placed on the undersurface of the lid of a Petri dish and incubated at 37°C. After 2 d of hanging drop culture, the cell aggregates contained in the drops were collected in 10 ml of EB medium and transferred to a bacterial Petri dish, where the aggregates were grown in suspension for 3 d. The aggregates were transferred onto a regular tissue culture dish, where they spread and differentiated. This was considered d 0. The differentiated cells are referred to as EBs. The medium was changed every 2 d. For fluorescence immunostaining, the EBs were plated onto gelatin-coated circular coverslips. When indicated, the following reagents were added to the EB culture medium at the time of the hanging drop step: recombinant LAP (3.2 μg/ml), recombinant TGF-β (1 ng/ml), rabbit anti-LTBP-1 antiserum Ab39 (1:200 dilution), or anti-TGF-β monoclonal antibody (5 μg/ml; Genzyme, Cambridge, MA). Fresh reagents were added every 2 d when the medium was changed.

Synthetic Oligonucleotides and Reverse Transcription (RT)-Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) Conditions

For each gene amplified by RT-PCR we used the primers and conditions described in Table 1. The primers were chosen so that they spanned at least one intron of the genes of interest

Table 1.

Oligonucleotide primers used for RT-PCR

| Gene | Primer sequence | Reference | Annealing Temperature (°C) | Size (bp) | No. of cycles |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LTBP-1 | 5′ GCAATCCTATCATGGATATAC 3′ 5′ GCGTAGGAGCAATCACTTGG 3′ | GENEBANK AF022889 | 56 | 800 600 | 27 |

| β-Actin | 5′ ATCTGGCACCACACCTTCTACAATGAGCTGCG 3′ 5′ CGTCATACTCCTGCTTGCTGATCCACATCTGC 3′ | Clontech Laboratories, Palo Alto, CA | 50–60 | 838 | 25–30 |

| G3PDH | 5′ ACCACAGTCCATGCCATCAC 3′ 5′ TCCACCACCCTGTTGCTGTA 3′ | Clontech Laboratories, Palo Alto, CA | 50–60 | 450 | 25–30 |

| ICAM-2 | 5′ GAGAAGGCCTTTGAGGTCTA 3′ 5′ ACAGCAGTATTGACACCACC 3′ | GENEBANK X65493 | 56 | 642 | 28 |

| vWF | 5′ AGTACCATGATGGCTCCCGT 3′ 5′ GGCATACTCCATGGTTACCG 3′ | Zanetta et al., 2000 | 60 | 600 | 30 |

| SM actin | 5′ CTGGAGAAGAGCTACGAACTGC 3′ 5′ CTGATCCACATCTGCTGGAAGG 3′ | Coleman et al., 1998 | 62 | 368 | 25 |

| Myf5 | 5′ GTTCTTTCGGGACCAGACAGGGCTG 3′ 5′ GAGCTGCTGAGGGAACAGGTGGAGA 3′ | Montarras et al., 1991 | 55 | 132 | 30 |

| αMHC | 5′ CTGCTGGAGAGGTTATTCCTCG 3′ 5′ GGAAGAGTGAGCGGCGCCATACAGG 3′ | Oyamada et al., 1996 | 56 | 302 | 25 |

| Cytokeratin K14 | 5′ GTGTCCACTGGCGATGTGAACGTGG 3′ 5′ GCTGCCGCAGTAGCGACTCTACTGT 3′ | Bagutti et al., 1996 | 64 | 330 | 33 |

| Neurofilament NFL | 5′ GTTGGGAATAGGGCTCAATCT 3′ 5′ CCAGGAAGAGCAGACAGAGGT 3′ | Rohwedel et al., 1998 | 60 | 302 | 25 |

| GFAP | 5′ AAGCTCCAAGATGAAACCAACCTGA 3′ 5′ GCAAACTTAGACCGATACCACTC 3′ | Carr et al., 1998 | 56 | 326 | 27 |

Primer pairs used for amplification of cell-specific genes from EBs with mouse-transcribed RNA.

RNA Extraction and Semiquantitative RT-PCR

All reagents used to perform the RT-PCR were purchased from Roche (Indianapolis, IN).

Total RNA was purified from the EBs at the times indicated using Trizol reagent (Life Technologies). Total RNA was treated with RNase-free DNase I (Roche) to eliminate possible contamination from genomic DNA. Total RNA (2.5 μg) was reverse transcribed using 2.5 μM random hexanucleotides and 40 U of murine Moloney leukemia viral reverse transcriptase in the presence of 40 U of RNase inhibitor in a final volume of 30 μl. The reaction was performed at 30°C for 10 min, followed by a further 90 min at 42°C. PCR reactions were performed using 5 μl of the reverse-transcribed RNA in the presence of the appropriate primers (0.4 μM), deoxyribonucleotide triphosphates (0.2 mM), and Taq polymerase (2.5 U) in 25 μl (final volume). To ensure that any products formed were derived from the reverse transcriptase reaction and not contaminating DNA, a control reaction was always performed in which the reverse transcriptase was omitted. Depending on the sizes of the amplified products of interest, the housekeeping genes glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (G3PDH) or β-actin were amplified in the same reaction tubes. This was accomplished by lowering the primer concentrations: β-actin primers were added at a final concentration of 0.025 μM, whereas the G3PDH primers were added at a final concentration of 0.08 μM. The PCRs consisted of an initial denaturation of the samples at 95°C for 3 min, followed by 25–35 cycles depending on which gene was amplified (see above). Each cycle consisted of a denaturation step at 95°C for 30 s, a 1-min annealing step at the temperatures specified above, and an extension step at 72°C for 2.5 min. A final extension cycle of 10 min at 72°C was added to each PCR. Preliminary experiments were performed in which the number of PCR cycles was varied and the signals for LTBP-1, β-actin, and G3PDH were analyzed to determine the linear portion of the assay with the individual primers. The number of cycles used for each experiment was within the linear range of the assay as determined by control experiments. The amplified products were analyzed on 1% agarose gels and visualized by ethidium bromide staining; the intensity of the bands was measured by scanning the Polaroid (Cambridge, MA) pictures of the gels, followed by densitometric analysis. Data are represented as percentages of the sum of the two LTBP-1 bands versus the control housekeeping gene. The data presented represent averages of values obtained from three to five experiments unless otherwise noted.

Indirect Immunofluorescence

EBs were seeded and grown for the times indicated on 12-mm glass coverslips coated with 0.1% gelatin (Kodak, Rochester, NY) in 24-well plates. Culture medium was removed, and the EBs were rinsed once with 0.1 M cacodylic acid, 1 mM CaCl2, 0.5 mM MgCl2, pH 7.4 (cacodylic buffer) and once with cacodylic buffer containing 1% goat serum (blocking buffer). The incubation with Ab39 was performed on live cells. EBs were incubated for 2 h at 37°C in a moist chamber with Ab39 diluted 1:500 in blocking buffer. After a wash with blocking buffer, the EBs were fixed and permeabilized with 95% ethanol for 10 min at room temperature. To rehydrate the fixed EBs, two incubations of 5 min each were performed at room temperature with blocking buffer. The signal was revealed using anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA) diluted 1:400 in blocking buffer. The samples were incubated for 1 h in a moist chamber at room temperature and rinsed three times with cacodylic buffer; the coverslips were mounted and analyzed using an Axiophot-2 microscope (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY).

To colocalize LTBP-1 fibers in the presence of smooth muscle, endothelial or epithelial cells, or neurons, the EBs were first stained with Ab39 and fixed as described above. After fixation, the samples were incubated with the anti-α-smooth muscle actin monoclonal antibody (Sigma; 1:300 dilution in blocking buffer), the purified rat anti-mouse ICAM-2 (CD102) monoclonal antibody (PharMingen, San Diego, CA; 1:200 dilution), the anti-cytokeratin (K8/18 LE-61) monoclonal antibody (gift of Prof. E.B. Lane, Dundee, Scotland), or the anti-neurofilament H monoclonal antibody (Sternberger, Lutherville, MD), diluted 1:1000 to detect smooth muscle cells, endothelial cells, epithelial cells, or neurons, respectively. After incubating three times for 5 min with blocking buffer, the coverslips were incubated with both FITC-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG to detect LTBP-1 and rhodamine-conjugated anti-rat IgG (Jackson Immunoresearch; 1:100 dilution) to detect endothelium or with rhodamine-conjugated anti-mouse IgG to detect actin stress fibers, and keratin fibers, or neurofilaments; all dilutions were made in blocking medium. All dilutions were made in blocking buffer. The coverslips were analyzed using a Zeiss Axiophot-2 microscope.

RESULTS

LTBP-1 Expression during In Vitro ES Cell Differentiation

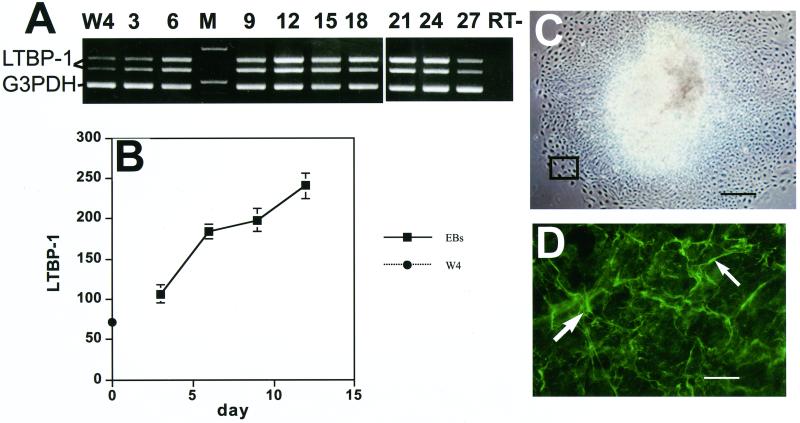

As an approach to study LTBP-1 during mouse embryonic development, we characterized LTBP-1 production by ES cells differentiating in vitro. LTBP-1 mRNA was expressed in W4 129 SvEv murine stem cells maintained in an undifferentiated state (Figure 1A). This result suggested that LTBP-1 might be important during the early stages of differentiation of ES cells. Therefore, we next analyzed LTBP-1 mRNA expression during the differentiation of W4 ES cells. LTBP-1 mRNA expression was monitored by RT-PCR with primers designed to detect two of the alternatively spliced isoforms of LTBP-1, as well as the housekeeping gene G3PDH as an internal control (Gong et al., 1998; Oklu et al., 1998). When the samples were analyzed by gel electrophoresis and stained with ethidium bromide, it was apparent that the two forms of LTBP-1 were present at all time points and appeared to increase in amount until d 12 (Figure 1A). The amount of LTBP-1 mRNA expressed at each time point was quantitated by densitometric analysis of the gel bands. The data are presented for each time point as the percentage of the value measured for the housekeeping gene band. The lowest expression of LTBP-1 mRNA was detectable in the undifferentiated W4 ES cells (Figure 1B). Expression increased significantly (4- to 5-fold) within the first 12 d of differentiation. The levels plateaued between d 12 and 24 and decreased after 24 d of culture (Gualandris, Annes, Arese, Noguera, Jurukovski, and Rifkin, our unpublished results). Because the standardization of the linearity of the PCR reaction was performed with relatively sparse cells, the results from the later times, d 12–27, may represent values not within the linear range of the assay. Therefore, these values indicate only the continued expression of LTBP-1 and must be considered to be merely qualitative.

Figure 1.

LTBP-1 expression by differentiating EBs. (A) RT-PCR analysis (days after plating). The two upper bands of 800 and 600 base pairs (bp) represent the two alternatively spliced isoforms of LTBP-1; the lowest band of 400 bp corresponds to the housekeeping gene G3PDH. The lane marked RT− represents the sample incubated in the absence of reverse transcriptase. M, markers for 1 and 0.5 kb. (B) Densitometric analysis of gel bands. The values from four different gels each representing a separate experiment were averaged. The values represent the percentages of the value for the two LTBP-1 bands versus the value for the housekeeping gene G3PDH for each lane. (C) Phase microscopy image (×40) of a 3-d-old EB. The outlined rectangle corresponds to the image shown in D. Bar, 250 μm. (D) Immunofluorescent staining of a 3-d-old EB with anti-LTBP-1 rabbit antiserum. White arrows show extracellular LTBP-1 fibers. Magnification, ×400. Bar, 25 μm.

To analyze LTBP-1 protein expression, EBs were immunostained with anti-LTBP-1 antiserum (Ab39) (Kanzaki et al., 1990). Figure 1C shows a 3-d-old EB attached to the surface of a tissue culture plate: the inner zone is denser than the peripheral zone because the inner zone contains overlapping cell layers derived from the original EB cell aggregate. By immunofluorescent staining, LTBP-1 immunoreactivity was observed as extracellular fibers specifically localized at the periphery of the growing EB (Figure 1D). This area undergoes constant cell growth and migration as cells from the central mass migrate out. The same pattern of staining was observed in this region at later time points (Gualandris, Annes, Arese, Noguera, Jurukovski, and Rifkin, our unpublished results). After d 12, some LTBP-1 fibers were also detected in the inner zone, which consists primarily of epithelium-like cells.

Time Course of ES Cell Differentiation

To test whether LTBP-1 plays a role in ES cell differentiation, we next determined the earliest appearance of specific cell lineage-specific markers in differentiating EBs using RT-PCR. Total RNA was purified from growing EBs every 3 d, and semiquantitative RT-PCR was performed with the primers described in MATERIALS AND METHODS. Consistent with previous reports, smooth muscle (Coleman et al., 1998), cardiac (Sanchez et al., 1991; Fassler et al., 1996; Oyamada et al., 1996; Drab et al., 1997), and endothelial cell markers (Vittet et al., 1996; Wartenberg et al., 1998) appeared within the first 6 d after the initiation of differentiation. Markers for the remaining cell types were detectable later, with markers for astrocytes being the last to appear (d 21). On d 15–30, the EBs had grown to a few millimeters in diameter. However, the peripheral area was still populated mainly by smooth muscle cells (see below), whereas within the inner area, different cell types were present without any particular spatial localization. Multiple beating foci of cardiac muscle cells and multinucleated myotubes were easily visualized in the inner area by phase microscopy. The remaining cell types, including epithelial, endothelial, and neuronal cells, were visualized only after fluorescent immunostaining with antibodies against their cell-specific markers. Epithelial cells usually comprised the envelope of cyst-like structures that developed in the central area, whereas endothelial cells were organized in cord-like arrays (see below). The time of appearance of representative markers was confirmed by RT-PCR for additional markers, such as myogenin for skeletal muscle (Montarras et al., 1991), ventricular myosin light chain 2 for cardiomyocytes (Wobus et al., 1997), enolase for neurons (Comer et al., 1997), PECAM for endothelial cells (Vittet et al., 1996), and keratin 18 for epithelium (Bagutti et al., 1996; Gualandris, Annes, Arese, Noguera, Jurukovski, and Rifkin, our unpublished results). The temporal appearance of the cell-specific mRNAs also correlated with the differentiation of the corresponding cell types as monitored by immunostaining of the EBs with cell-specific antibodies (Gualandris, Annes, Arese, Noguera, Jurukovski, and Rifkin, our unpublished results). The only exceptions were neuronal and epithelial cells. Mature neurons could be visualized by immunostaining with anti-neurofilament antibody only after 21 d, whereas their markers were detected by RT-PCR at 12 d. The epithelial markers keratin-8 (K8) and keratin-18 (K18), which are indicative of simple epithelium, were detectable by immunostaining by d 6 (Gualandris, Annes, Arese, Noguera, Jurukovski, and Rifkin, our unpublished results), although RT-PCR analysis showed that the basal epithelial marker K14 was not expressed until d 15.

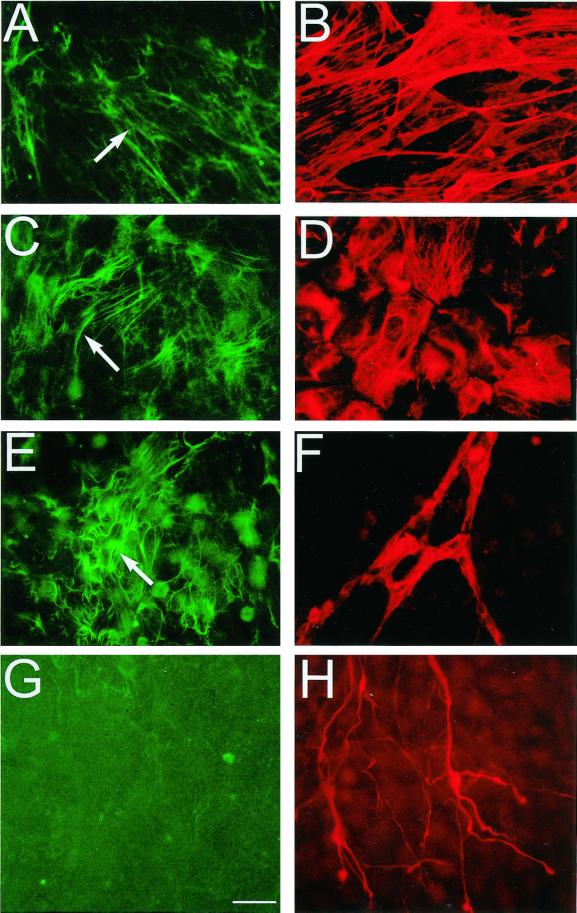

Colocalization of LTBP-1 Fibers with Differentiating ES Cells

To determine with which of the several cell types present in different cultures LTBP-1 fibers colocalize, 12-d-old EBs were double immunostained with Ab39 to detect LTBP-1 and with antibodies specific for individual cell types. These antibodies included an anti-smooth muscle actin antibody to detect smooth muscle cells, an anti-epithelial cytokeratin antibody to detect epithelial cells, an anti-ICAM-2 antibody to detect endothelial cells, and an anti-neurofilament antibody to detect neuronal cells. In Figure 2, A, C, E, and G, show fields stained for LTBP-1. Figure 2B represents the field illustrated in Figure 2A costained with anti-smooth muscle actin antibody. Likewise, Figure 2D illustrates the field illustrated in Figure 2C costained with anti-epithelial cytokeratin antibody. Smooth muscle cells were localized in the periphery of the growing EBs (Figure 2B), where no other cell types were detected. Conversely, epithelial cells and LTBP-1 fibers (Figure 2C) colocalized in regions with multiple cell layers. For endothelial cells (Figure 2D), branched cord-like aggregates of cells that stained positively with the anti-ICAM-2 antibody developed within a multilayered extracellular environment enriched in LTBP-1 fibers (Figure 2, E and F). These endothelial structures resembled the aggregates of endothelial cells reported to occur in differentiating EBs (Vittet et al., 1996, 1997; Goumans et al., 1999; Hidaka et al., 1999) and may be related to the tube-like structures induced by TGF-β in cultures of endothelial cells (Basson et al., 1992; Madri et al., 1992). Other cell types, such as neurons (Figure 2, G and H), skeletal muscle cells, and cardiomyocytes (Gualandris, Annes, Arese, Noguera, Jurukovski, and Rifkin, our unpublished results) developed in areas devoid of LTBP-1 fibers. The distribution of the LTBP-1 was not coincident with individual cells but was restricted to specific regions populated by certain cell types, as would be expected for a matrix rather than cell surface protein. This result suggests that cells in those regions that contained organized LTBP-1 synthesized that LTBP-1, promoted LTBP-1 fibril formation, or both. Thus, in EB cultures the organization of LTBP-1 fibers in the ECM is regulated spatially and temporally.

Figure 2.

Colocalization of LTBP-1 fibers with smooth muscle cells (A and B), epithelial cells (C and D), endothelial cells (E and F), and neurons (G and H). Twelve-day-old EBs were incubated with rabbit polyclonal anti-LTBP-1 serum Ab39, fixed, and incubated with either mouse monoclonal anti-smooth muscle actin antibody (B), mouse monoclonal anti-cytokeratin K18/8 antibody (D), the rat monoclonal anti-ICAM-2 antibody (F), or a mixture of two mouse monoclonal antibodies, SM31 and SM32 (H) raised against neurofilaments. Antigen–antibody complexes were detected with FITC-conjugated anti-rabbit, anti-mouse, or anti-rat IgG antibodies. Magnification, ×400. Bar, 25 μm.

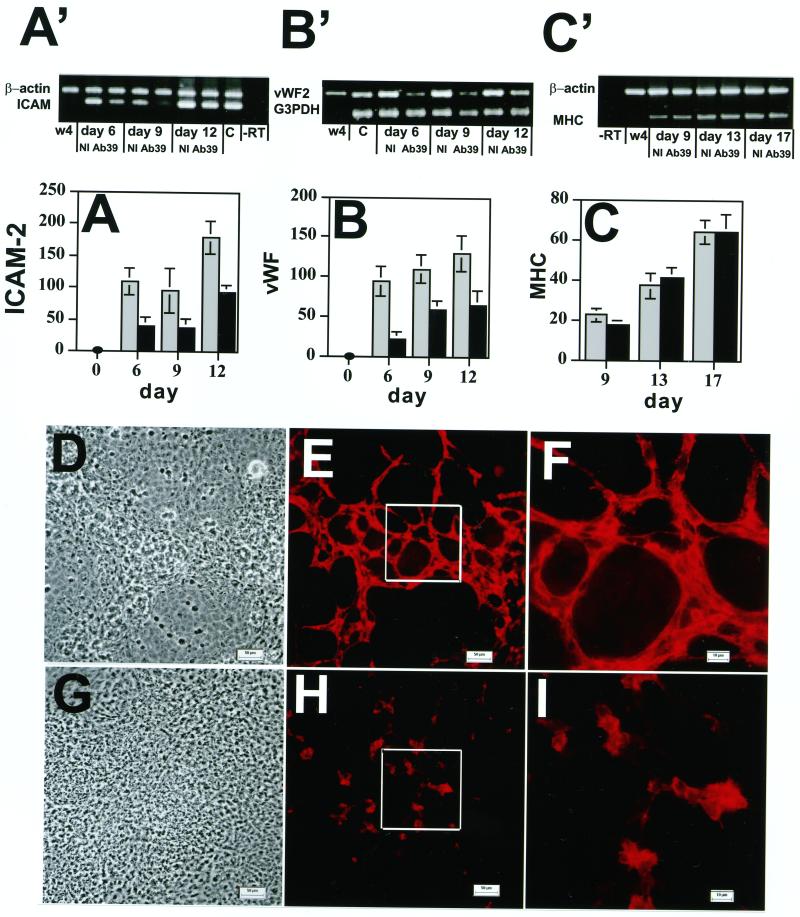

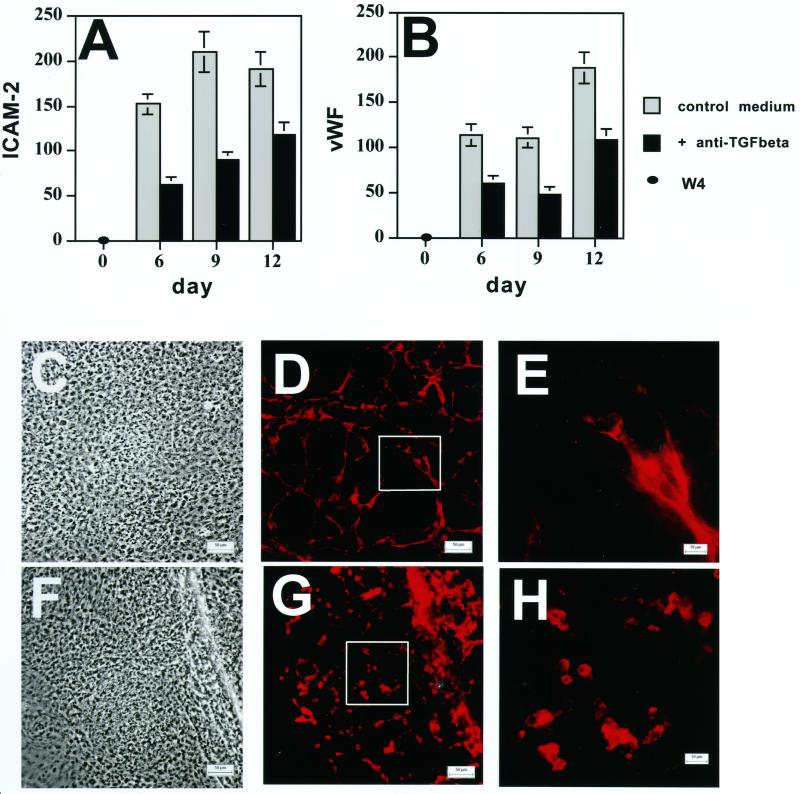

Effect of Anti-LTBP-1 Antibody on Endothelial Cell Markers

To study the association of LTBP-1 with cellular differentiation and organization of specific structures, we monitored the effect of Ab39 on the in vitro differentiation of EB cells both by displaying the amplified markers by gel electrophoresis and by scanning the bands for individual markers from multiple gels and comparing the values for the marker bands to those of internal control housekeeping gene bands. As shown in Figure 3 (A′ and B′ and A and B), the expression of two endothelial cell-specific genes, ICAM-2 and von Willebrand factor (vWF), was significantly down-regulated by Ab39 between d 6 and 12. Similar results were obtained with the endothelial marker PECAM (Gualandris, Annes, Arese, Noguera, Jurukovski, and Rifkin, our unpublished results). The appearance of markers for other cell types, such as αMHC for cardiac muscle cells (Figure 3C′ and C) or K14 for epithelial cells (Gualandris, Annes, Arese, Noguera, Jurukovski, and Rifkin, our unpublished results), were not affected by exposure to Ab39. This finding rules out the possibility that Ab39 interferes generally with the basal differentiation mechanisms of the ES cells and suggested a specific role of LTBP-1 in endothelial cell differentiation.

Figure 3.

Effect of anti-LTBP-1 antibody on the expression of the endothelial cell markers ICAM-2 and vWF and the formation of vessel-like structures. EBs were grown in the presence of Ab39 (1:200) or nonimmune (NI) rabbit serum (1:200) for 21 d. The expression of ICAM-2 (A′ and A), vWF (B′ and B), and αMHC (C′ and C) was measured by RT-PCR at the indicated time points. The RT-PCR products were analyzed by gel electrophoresis (Figure 3A′, B′, and C′). W4 represents samples amplified from ES cells, and C represents samples amplified from adult mouse tissue as a positive control.−RT represents samples amplified in the absence of RT. The values for the individual bands measured after densitometry of the amplification products are presented as percentages of values of the housekeeping genes β-actin or G3PDH (A, B, and C). These values represent averages from four experiments. The gray bars represent values from cells treated with nonimmune serum and the black bars represent values from cells treated with antibody 39. Nine-day-old EBs, grown in the presence of nonimmune rabbit serum (D–F) or Ab39 (G–I), were also characterized by light microscopy (D and G) and by indirect immunofluorescence (E, F, H, and I) with anti-ICAM-2 antibody to detect differentiated endothelial cells. The outlined boxes in E and H indicate the fields represented at higher magnification in F and I. Magnifications, ×200 (D, E, G, and H); ×630 (F and I). Bars, 50 μm (D and G); 10 μm (E, F, H, and I.

To determine whether the decrease in the mRNA levels of the endothelial cell markers reflected an altered phenotype of the endothelial cells, 9-d-old EBs grown in the presence or absence of Ab39 were immunostained with anti-ICAM-2 antibody. As visualized by light microscopy (Figure 3D) cultures treated with nonimmune serum consisted of areas of multilayered cells interspersed with areas of flatter less refractile cells. When the same fields from these cultures were examined by immunofluorescence, a branched network of cord-like structures consisting of multiple endothelial cells was visible (Figure 3D). These endothelial cells were found primarily in the dense multilayered areas visualized by light microscopy. At higher magnification, the positive cells appeared to form branching aggregates (Figure 3F). In contrast, EBs grown in the presence of Ab39 consisted of a monolayer of constant cell density (Figure 3G). When examined by immunofluorescence microscopy, clusters of ICAM-2–positive cells that showed little branching or cord-like structures were observed (Figure 3, H and I). The lack of endothelial cell organization observed in the EBs treated with Ab39 was a transient phenomenon. After 15 d of culture in the presence of Ab39 the endothelial cells formed branched structures equivalent to those that developed in control medium (Gualandris, Annes, Arese, Noguera, Jurukovski, and Rifkin, our unpublished results). Thus, antagonizing LTBP-1 with a specific antibody delays but does not prevent the formation of cord-like structures by endothelial cells.

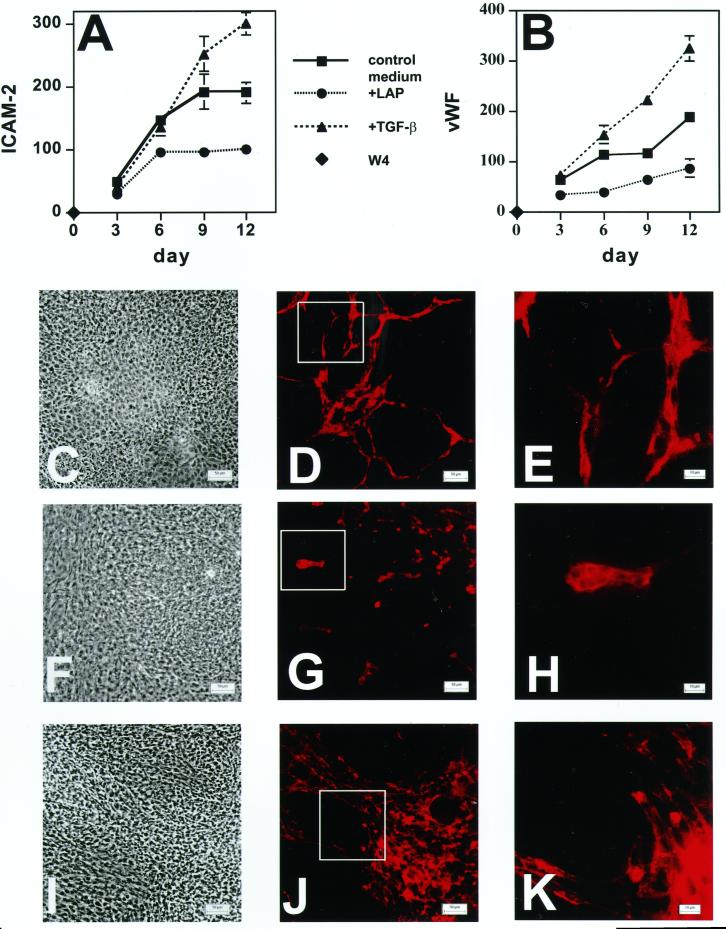

Involvement of TGF-β in ES Cell Differentiation

Because LTBP-1 can modulate latent TGF-β activation (Flaumenhaft et al., 1993; Nunes et al., 1997), we tested whether the effect of LTBP-1 on endothelial cell differentiation was modulated by TGF-β. For this purpose, EBs were grown in medium containing either recombinant TGF-β1 or recombinant LAP. Endothelial cell differentiation was analyzed by amplifying the endothelial cell-specific ICAM-2 and vWF transcripts at different times and characterizing the ICAM-2, vWF, and housekeeping RT-PCR products as described for Figure 3. LAP associates with active TGF-β to form a latent complex, thereby blocking the action of TGF-β (Gentry et al., 1987). Both endothelial cell-specific markers were up-regulated by TGF-β1 (1 ng/ml), whereas LAP (30 μg/ml) had the opposite effect (Figure 4, A and B). The effect of LAP was similar to, but stronger than, the effect of Ab39 (Figure 3).

Figure 4.

Effect of LAP or TGF-β on the expression of the endothelial cell markers ICAM-2 (A) and vWF (B) and on formation of vessel-like structures in EBs (C–K). EBs were grown for 21 d in control culture medium or in medium supplemented with either recombinant LAP (3.2 μg/ml) or recombinant TGF-β1 (1 ng/ml). ICAM-2 (A) and vWF (B) expression was measured by RT-PCR. The values obtained by densitometry for the bands of each endothelial marker are presented as percentages of the values for the housekeeping gene β-actin. The values represent the averages compiled from five gels. Nine-day-old EBs grown in the presence of recombinant LAP (3.2 μg/ml; F–H), recombinant TGF-β1 (1 ng/ml; I–K), or control medium (C–E) were also characterized by light microscopy (C, F, and I) and by indirect immunofluorescence (D, E, G, H, J, and K) with anti-ICAM-2 antibody. The outlined boxes in D, G, and J indicate fields shown at higher magnification in E, H, and K, respectively. Magnifications, ×200 (C, D, F, G, I, and J); ×630 (E, H, and K). Bars, 50 μm (C, D, F, G, I, and J); 10 μm (E, H, and K).

To test whether LAP and TGF-β1 also affected cell organization into cord-like structures, 9-d-old EBs were immunostained with an anti-ICAM-2 antibody. As shown in Figure 4 (D and E versus G and H), LAP significantly inhibited the formation of the cord-like structures by the endothelial cells. However, LAP did not completely abolish the differentiation process, because some endothelial cells were still detectable as clusters of cells. Moreover, as was observed with Ab39, the effect was transient: after 15 d of culture, LAP-treated EBs also developed branched structures (Gualandris, Annes, Arese, Noguera, Jurukovski, and Rifkin, our unpublished results). By light microscopy, there was little difference between control (Figure 4C) versus LAP-treated cultures (Figure 4F). On the contrary, recombinant TGF-β1 appeared to induce the formation of more abundant and denser cords (Figure 4, J and K versus D and E) and to increase the total number of ICAM-positive cells relative to control medium. The simultaneous addition of recombinant TGF-β1 and Ab39 to EB cultures had the same effect on the expression of the ICAM-2 and vWF messages as recombinant TGF-β1 alone (Gualandris, Annes, Arese, Noguera, Jurukovski, and Rifkin, our unpublished results). Therefore, excess TGF-β1 can overcome the inhibition of endothelial cell differentiation by Ab39. Although these data did not define when and how TGF-β1 plays a role in the process of differentiation of the endothelium, they strongly suggest that TGF-β1 and, consequently, the modulation of TGF-β1 availability are important in the formation of cord-like structures as well as the expression of specific endothelial markers.

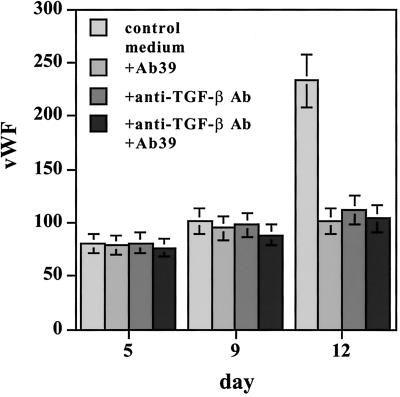

Effect of Anti-TGF-β Antibody on Cord Formation during ES Cell Differentiation

The observation that both Ab39 and recombinant LAP affected the formation of branched structures, and that recombinant TGF-β1 overcame the inhibition elicited by Ab39, indicated a potential involvement of TGF-β in this endothelial cell differentiation. However, in addition to forming a complex with TGF-β, LAP can bind to certain integrins in an RGD-dependent manner (Munger et al., 1998). Therefore, LAP may exert its biological effects through a TGF-β–independent mechanism(s). To rule out the possibility that the phenotype observed in LAP-treated EBs resulted from an integrin-mediated mechanism and to support our hypothesis that TGF-β formation was required for endothelial cell cord formation, EBs were grown in the presence or absence of a monoclonal anti-TGF-β antibody that recognizes all three forms of TGF-β, and expression of the endothelial cell markers ICAM-2 and vWF was characterized by RT-PCR as described. As was observed with Ab39, the expression of both markers was down-regulated by anti-TGF-β antibody (Figure 5, A and B). Therefore, this antibody had effects similar to those obtained with Ab39 or LAP (Figures 3 and 4). The TGF-β antibody also delayed the formation of branched structures as revealed by immunofluorescent staining of 9-d-old EBs with anti-ICAM-2 antibody (Figure 5, D and E versus G and H). These data clearly indicated that, in this in vitro differentiation model, TGF-β is involved in the maturation of cord-like structures by differentiating endothelial cells. Treatment with anti-TGF-β antibody in combination with Ab39 decreased vWF mRNA expression to the same extent as each antibody alone (Figure 6), even though the induction of vWF in this experiment appeared to be slightly delayed compared with the induction observed in earlier experiments. The failure of the combination of antibodies to reduce vWF expression more than either alone implies that both antibodies act through the same mechanism, which appears to be a reduction of active TGF-β.

Figure 5.

Effect of anti-TGF-β antibody on the expression of the endothelial cell markers ICAM-2 (A) and vWF (B) in the presence of anti-TGF-β and on formation of vessel-like structures in EBs (C and H). EBs grown in the presence or absence of monoclonal anti-TGF-β antibody (15 μg/ml) were analyzed for ICAM-2 (A) and vWF (B) expression by RT-PCR. The values obtained by densitometry of the bands are presented as percentages of the values obtained for the housekeeping gene β-actin. The values represent the averages obtained from three gels. Nine-day-old EBs grown in the presence (F–H) or in the absence (C–E) of anti-TGFβ antibody were analyzed by light microscopy (C and F) and by indirect immunofluorescence (D, E, G, and H) with ICAM-2 antibody to detect endothelial cells forming vessel-like structures. Magnifications, ×200 (C, D, F, and G); ×630 (E and H). Bars, 50 μm (C, D, F, and G; 10 μm (E and H). The outlined boxes in D and G indicate the fields illustrated at higher magnification in E and H.

Figure 6.

Effect of anti-TGF-β antibody (Ab) alone or in combination with Ab39 on the expression of vWF mRNA in EBs. EBs grown for the indicated times in the absence or presence of either anti-TGF-β antibody (15 μg/ml), Ab39 (1:200), or both antibodies were characterized for vWF expression by RT-PCR. The values obtained after the densitometry of the bands are presented as percentages of the housekeeping gene G3PDH. The values presented represent the averages from three gels.

DISCUSSION

The capacity of ES cells to differentiate in vitro into multiple cell lineages that organize into primitive organ-like structures has been known for many years (Wiles, 1995; O'Shea, 1999). ES cell differentiation mimics certain events in early embryogenesis, and ES cells have been used to analyze the maturation of several cell types, including muscle (Sanchez et al., 1991; Rohwedel et al., 1994), epithelial (Bagutti et al., 1996), hematopoietic (Keller et al., 1993; Nakano et al., 1994), and endothelial cells (Vittet et al., 1996; Hirashima et al., 1999). Compared with other ES cell strains, the W4 129 SvEv ES cells showed a broad spectrum of differentiation under standard conditions. By RT-PCR and immunofluorescent staining of cells in EBs, we observed the appearance of multiple cell types such as smooth muscle, cardiac and skeletal muscle, epithelial, endothelial, and neuronal cells. On this basis, we used W4 ES cells as a system to characterize LTBP-1 expression and function during differentiation. Here we show that antibody to LTBP-1 temporarily blocks the maturation and organization of endothelial cells into cord-like structures during the in vitro differentiation of ES cells.

Although LTBP-1 expression in adult tissues has been studied, little is known about LTBP-1 in development. LTBP-1 codistributes with TGF-β1 in extracellular fibers during cardiogenesis, where it may regulate endothelial–mesenchymal transformation (Nakajima et al., 1997). In the 9.5-d-old mouse embryo, during the formation of the dorsal aorta, LTBP-1 fibrillar immunoreactivity was observed in areas surrounding migrating smooth muscle cells (Nakajima et al., 1999). Furthermore, the analysis of LTBP-1 expression by immunohistochemistry of tissue sections of mouse embryos showed that LTBP-1 is organized in extracellular fibers within mesenchymal tissues of multiple developing organs and in the basement membranes of epithelia involved in epithelial–mesenchymal interactions (Nakajima et al., 1999). On the basis of these results, Nakajima et al. (1999) proposed that LTBP-1 may play a role during embryogenesis, especially at sites that undergo tissue remodeling.

Within growing EBs, we observed that endothelial, smooth muscle, and epithelial cells developed in microenvironments containing LTBP-1 fibers (Figure 2). The fact that some cell types such as neurons (Figure 2, G and H), skeletal muscle cells, and cardiac myocytes (Gualandris, Annes, Arese, Noguera, Jurukovski, and Rifkin, our unpublished results) appeared in regions devoid of LTBP-1 fibers indicates that there was a specificity to the distribution of LTBP-1. LTBP-1 fibers were detectable in the peripheral region of EBs of all ages (Figure 1, C and D). This area contained primarily smooth muscle cells (Figure 2, A and B) that continuously proliferate and migrate as new cells differentiate in the center of the EB. The LTBP-1 fibrils may support the movement of smooth muscle cells as reported for adult smooth muscle cells (Shiima et al., 1998).

The involvement of LTBP-1 in W4 ES cell differentiation is supported by our observation that an antiserum to LTBP-1, Ab39, which blocks TGF-β activation, inhibits both the expression of endothelial cell markers and the formation of branched structures by these cells (Figure 3). Thus, Ab39 affects both the maturation and organization of endothelial cells. The effect of Ab39 on two other biological systems has been described: Ab39 inhibits bone nodule formation in cultures of rat calvarial cells (Dallas et al., 1995) and blocks the formation of endocardial cushion tissue during mouse embryogenesis (Nakajima et al., 1997). The mechanism(s) by which LTBP-1 exerts these effects is (are) not understood. During bone nodule formation, a structural role for LTBP-1 as an ECM protein has been proposed, whereas in the cardiogenic process, LTBP-1 is believed to be important for TGF-β activation. Our data point to a role for LTBP-1 as a potential modulator of TGF-β availability. This conclusion is based on our observations that recombinant TGF-β counteracts and TGF-β–neutralizing molecules mimic the effect of Ab39 on the formation of cord-like endothelial structures. This result is similar to that reported for endothelial–mesenchymal transformation (Nakajima et al., 1997) and implicates the involvement of active TGF-β in this system. In addition our findings that both anti-TGF-β antibody and LAP elicit the same phenotype as Ab39, whereas recombinant TGF-β potentiates endothelial cord formation, further support our conclusion.

Although our data are consistent with the hypothesis that Ab39 modifies the ability of LTBP-1 to participate in latent TGF-β activation, we were unable to measure the production of active TGF-β by cultures of EBs. The reasons for this are not clear because the inhibition of endothelial cell differentiation by LAP and a monoclonal antibody to TGF-β imply that active TGF-β is present and effective under normal conditions. It is possible that, because of the structure of the EBs, the reporter cells we used (Abe et al., 1994), but not the antibodies or LAP, were prevented from detecting locally active TGF-β. A failure to detect soluble TGF-β during integrin-mediated activation of latent TGF-β has been described previously (Munger et al., 1999).

The participation of TGF-β in ES cell differentiation into organized endothelium has been suggested by several groups. Undifferentiated ES cells are resistant to TGF-β; however, as soon as LIF is removed, they begin to express TGF-β-RII and become responsive to the active cytokine (Goumans et al., 1998; Slager et al., 1993; Thorsteinsdottir et al., 1999). In agreement with our observation that recombinant TGF-β supports the formation of cord-like structures, Zhang et al. (1998) found that overexpression of TGF-β1 in a strain of ES cells unable to differentiate into mature endothelium conferred the capacity to form tubular structures when cultured as EBs. Furthermore, expression of a dominant negative TGF-βRII (ΔTβRII) in a clone of ES cells did not compromise their differentiation into endothelial cells but did interfere with the capacity of the cells to organize (Goumans et al., 1999). This effect lasted for up to 20 d of growth of the EBs. In our experiments, the presence of anti-LTBP-1 and/or anti-TGF-β antibodies delayed the formation of branched structures for a shorter time. This result may indicate that the blockage of the TGF-β pathway by the expression of a dominant negative receptor is more effective than the addition of antagonizing antibodies to the culture medium. Goumans et al. (1999) also showed that the yolk sac of chimeric embryos obtained by aggregation of ΔTβRII ES cells with morulae derived from a host mouse had defective vasculogenesis. (It is not known whether LTBP-1 is present in the yolk sac.) These data emphasize the importance of efficient regulation of TGF-β activation for embryonic vasculogenesis and hematopoiesis.

The delay in the formation of organized endothelial structures obtained with Ab39 was not potentiated by the coadministration of anti-TGF-β antibody (Figure 6). This finding suggests that either both antibodies act through the same mechanism or each antibody was maximally effective at the concentration used. The effect of anti-TGF-β antibody as an antivasculogenic agent was shown by Liu et al., (1999): injection of neonatal rats with a neutralizing antibody to TGF-β1 delayed glomerular capillary formation. The monoclonal anti-TGF-β antibody we used neutralizes all three TGF-β isoforms. Therefore, we do not know which isoform(s) of TGF-β is (are) important for endothelial cell differentiation. By RT-PCR we found that EBs of increasing ages express TGF-β receptors I and II (Gualandris, Annes, Arese, Noguera, Jurukovski, and Rifkin, our unpublished results). Only TGF-β1 knock-out mice develop a deficiency in yolk sac vasculogenesis (Dickson et al., 1995), in contrast to TGF-β2 and -β3 null mice (Kaartinen et al., 1995; Proetzel et al., 1995; Sanford et al., 1997). This observation suggests that TGF-β1 is the isoform required for formation of mature vasculature. Our data are in agreement with the phenotype observed in vivo not only with TGF-β1 knock-out mice but with TGF-βRII and SMAD-5 null mice (Oshima et al., 1996; Yang et al., 1999), which also show defects in vasculogenesis.

Thus, EBs represent a suitable system for addressing the biological functions and role of TGF-β and of LTBPs in differentiation and cell lineage commitment. In addition to characterizing LTBP-1 action, the molecular cues for endothelial cell differentiation can be investigated under conditions that permit manipulation. Moreover, the signals, both extra- and intracellular, required for endothelial cell assembly into branched cord-like structures can be probed.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Dr. David Moscatelli, Dr. Paolo Mignatti, and Dr. Natalina Quarto for interesting discussions and reading of the manuscript. We thank Melinda Vassallo and Wojtek Auerbach for technical assistance. We also thank Dr. Anna Maria Curatola, Dr. D. J. L. Salzer, and Dr. E. B. Lane, for providing, respectively, the anti-ICAM-2, the antineurofilament, and the anticytokeratin antibodies. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations used:

- bp

base pairs

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- EMFI

embryonic mouse fibroblast cells

- ES

embryonic stem

- FITC

fluorescein isothiocyanate

- G3PDH

glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- Ig

immunoglobulin

- LAP

latency-associated peptide

- LIF

leukemia inhibitory factor

- LLC

large latent complex

- LTBP

latent TGF-β–binding protein

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- RT

reverse transcription

- TGF-β

transforming growth factor-β

- vWF

von Willebrand factor

REFERENCES

- Abe M, Harpel JG, Metz CN, Nunes I, Loskutoff DJ, Rifkin DB. An assay for transforming growth factor-β using cells transfected with a plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 promoter luciferase construct. Anal Biochem. 1994;216:276–284. doi: 10.1006/abio.1994.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angelov DN, Arnhold S, Andressen C, Grabsch H, Puschmann M, Hescheler J, Addicks K. Temporospatial relationship between macroglia and microglia during in vitro differentiation of murine stem cells. Dev Neurosci. 1998;20:42–51. doi: 10.1159/000017297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagutti C, Wobus AM, Fassler R, Watt FM. Differentiation of embryonal stem cells into keratinocytes: comparison of wild-type and β1 integrin-deficient cells. Dev Biol. 1996;179:184–196. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailly S, Brand C, Chambaz EM, Feige JJ. Analysis of small latent transforming growth factor-β complex formation and dissociation by surface plasmon resonance. Absence of direct interaction with thrombospondins. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:16329–16334. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.26.16329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bain G, Kitchens D, Yao M, Huettner JE, Gottlieb DI. Embryonic stem cells express neuronal properties in vitro. Dev Biol. 1995;168:342–357. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basson CT, Kocher O, Basson MD, Asis A, Madri JA. Differential modulation of vascular cell integrin and extracellular matrix expression in vitro by TGF-beta correlates with reciprocal effects on cell migration. J Cell Physiol. 1992;153:118–128. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041530116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr DJJ, Veress LA, Noisakram S, Campbell IL. Astrocyte-targeted expression of IFN-alpha1 protects mice from acute ocular herpes simplex virus type 1 infection. J Immunol. 1998;161:4859–4865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman C, Zhao J, Gupta M, Buckley S, Tefft JD, Wuenschell CW, Minoo P, Anderson KD, Warburton D. Inhibition of vascular and epithelial differentiation in murine nitrofen-induced diaphragmatic hernia. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:L636–646. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.274.4.L636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comer AM, Yip S, Lipski J. Detection of weakly expressed genes in the rostral ventrolateral medulla of the rat using micropunch and reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction techniques. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1997;24:755–759. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1997.tb02127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallas SL, Keene DR, Bruder SP, Saharinen J, Sakai LY, Mundy GR, Bonewald LF. Role of the latent transforming growth factor β binding protein 1 in fibrillin-containing microfibrils in bone cells in vitro and in vivo. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:68–81. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallas SL, Miyazono K, Skerry TM, Mundy GR, Bonewald LF. Dual role for the latent transforming growth factor-β binding protein in storage of latent TGFβ in the extracellular matrix and as a structural matrix protein. J Cell Biol. 1995;131:539–549. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.2.539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson MC, Martin JS, Cousins FM, Kulkarni AB, Karlsson S, Akhurst RJ. Defective hematopoiesis and vasculogenesis in transforming growth factor-β1 knock out mice. Development. 1995;121:1845–1854. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.6.1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drab M, Haller H, Bychkov R, Erdmann B, Lindschau C, Haase H, Morano I, Luft FC, Wobus AM. From totipotent embryonic stem cells to spontaneously contracting smooth muscle cells: a retinoic acid and db-cAMP in vitro differentiation model. FASEB J. 1997;11:905–915. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.11.11.9285489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fassler R, Rohwedel J, Maltsev V, Bloch W, Lentini S, Guan K, Gulberg D, Hescheler J, Addicks K, Wobus AM. Differentiation and integrity of cardiac muscle cells are impaired in the absence of β1 integrin. J Cell Sci. 1996;109:2989–2999. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.13.2989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaumenhaft R, Abe M, Sato Y, Miyazono K, Harpel J, Heldin C-H, Rifkin DB. Role of the latent TGFβ binding protein in the activation of latent TGFβ by co-cultures of endothelial and smooth muscle cells. J Cell Biol. 1993;120:995–1002. doi: 10.1083/jcb.120.4.995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraichard A, Chassande O, Bilbaut G, Dehay C, Savatier P, Samarut J. In vitro differentiation of embryonic stem cells into glial cells and functional neurons. J Cell Sci. 1995;108:3181–3188. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.10.3181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentry LE, Webb NR, Lim GJ, Brunner AM, Ranchalis JE, Twardzik DR, Lioubin MN, Marquardt H, Purchio AF. Type 1 transforming growth factor beta: amplified expression and secretion of mature and precursor polypeptides in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:3418–3427. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.10.3418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giltay R, Kostka G, Timpl R. Sequence and expression of a novel member (LTBP-4) of the family of latent transforming growth factor β-binding proteins. FEBS Lett. 1997;411:164–168. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00685-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleizes P-E, Beavis RC, Mazzieri R, Shen B, Rifkin DB. Identification and characterization of an eight-cysteine repeat of the latent transforming growth factor-β binding protein-1 that mediates bonding to the latent transforming growth factor-β1. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:29891–29896. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.47.29891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleizes P-E, Munger JS, Nunes I, Harpel JG, Mazzieri R, Noguera I, Rifkin DB. TGF-β latency: biological significance and mechanisms of activation. Stem Cells (Dayton) 1997;15:190–197. doi: 10.1002/stem.150190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong W, Roth S, Michel K, Gressner AM. Isoforms and splice variant of transforming growth factor β-binding protein in rat hepatic stellate cells. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:352–363. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70488-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goumans M-J, Ward-van Oostwaard D, Wianny F, Savatier P, Zwijsen A, Mummery C. Mouse embryonic stem cells with aberrant transforming growth factor-β signaling exhibit impaired differentiation in vitro and in vivo. Differentiation. 1998;63:101–103. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.1998.6330101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goumans M-J, Zwijsen A, van Rooijen MA, Huylebroeck D, Roelen BA, Mummery CL. Transforming growth factor-β signaling in extraembryonic mesoderm is required for yolk sac vasculogenesis in mice. Development. 1999;126:3473–3483. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.16.3473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidaka M, Stanford WL, Bernstein A. Conditional requirement for the Flk-1 receptor in the in vitro generation of early hematopoietic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:7370–7375. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirashima M, Kataoka H, Nishikawa S, Matsuyoshi N, Nishikawa S-I. Maturation of embryonic stem cells in an in vitro model of vasculogenesis. Blood. 1999;93:1253–1263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaartinen V, Voncken JW, Shuler C, Warburton D, Bu D, Heisterkamp N, Groffen J. Abnormal lung development and cleft palate in mice lacking TGF-β3 indicates defects of epithelial-mesenchymal interaction. Nat Genet. 1995;11:415–421. doi: 10.1038/ng1295-415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanzaki T, Olofsson A, Moren A, Wernstedt C, Hellman U, Miyazono K. TGF-β1 binding protein: a component of the large latent complex of TGF-β1 with multiple repeat sequences. Cell. 1990;61:1051–1061. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90069-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanzaki T, Shiina R, Saito Y, Oohasi H, Morisaki N. Role of latent TGF-β 1 binding protein in vascular remodeling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;246:26–30. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller GM. In vitro differentiation of embryonic stem cells. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1995;7:862–869. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(95)80071-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller GM, Kennedy M, Papayannopoulou T, Wiles M. Hematopoietic commitment during embryonic stem cell differentiation in culture. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:473–486. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.1.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda M, Sok J, Webb L, Baechtold H, Urano F, Yin Y, Chung P, de Rooij DG, Akhemodv A, Ashley T, Ron D. Male sterility and enhanced radiation sensitivity in TLS(−/−) mice. EMBO J. 2000;19:453–462. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.3.453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Song D, Joyner AL. Two Pax2/5/8-binding sites in Engrailed2 are required for proper initiation of endogenous mid-hindbrain expression. Mech Dev. 2000;90:155–165. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(99)00242-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu A, Dardik A, Ballermann B. Neutralizing TGF-β1 antibody infusion in neonatal rat delays in vivo glomerular capillary formation. Kidney Int. 1999;56:1334–1348. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madri JA, Bell L, Merwin JR. Modulation of vascular cell behavior by transforming factors beta. Mol Reprod Dev. 1992;32:121–126. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1080320207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DM, Ogawa Y, Iwata KK, ten Dijke P, Purchio AF, Soloff MS, Gentry LE. Characterization of the binding of transforming growth factor-β1, -β2, and -β3 to recombinant β1-latency-associated peptide. Mol Endocrinol. 1992;6:694–702. doi: 10.1210/mend.6.5.1603080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazono K, Hellman U, Wernstedt C, Heldin CH. Latent high molecular weight complex of transforming growth factor-β1: purification from human platelets and structural characterization. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:6407–6415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montarras D, Chelly J, Bober E, Arnold H, Ott MO, Gros F, Pinset C. Developmental patterns in the expression of Myf5, MyoD, myogenin, and MRF4 during myogenesis. New Biol. 1991;3:592–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moren A, Olofsson A, Stenman G, Sahalin P, Kanzaki T, Claesson-Welsh L, ten Dijke P, Miyazono K, Heldin CH. Identification and characterization of LTBP-2, a novel latent transforming growth factor β binding protein. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:32469–32478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munger JS, Harpel JG, Giancotti FG, Rifkin DB. Interactions between growth factors and integrins: latent forms of transforming growth factor-β are ligands for the integrin αvβ1. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:2627–2638. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.9.2627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munger JS, Harpel JG, Gleizes P-E, Mazzieri R, Nunes I, Rifkin DB. Latent transforming growth factor-β: structural features and mechanisms of activation. Kidney Int. 1997;51:1376–1382. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munger JS, Huang X, Kawakatsu H, Griffiths MJD, Dalton SL, Wu J, Pittet J-F, Kaminski N, Garat G, Matthay MA, Rifkin DB, Sheppard D. The integrin αvβ6 binds and activates latent TGFβ1: a mechanism for regulation pulmonary inflammation and fibrosis. Cell. 1999;96:319–328. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80545-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima Y, Miyazono K, Kato M, Takase M, Yamagishi T, Nakamura H. Extracellular fibrillar structure of latent TGFβ binding protein-1: role in TGFβ-dependent endothelial-mesenchymal transformation during endothelial cushion tissue formation in mouse embryonic heart. J Cell Biol. 1997;136:193–204. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.1.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima Y, Miyazono K, Nakamura H. Immunolocalization of latent transforming growth factor-β binding protein-1 (LTBP1) during mouse development: possible roles in epithelial and mesenchymal cytodifferentiation. Cell Tissue Res. 1999;295:257–267. doi: 10.1007/s004410051232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano T, Kodama H, Honjo T. Generation of lymphohematopoietic cells from embryonic stem cells in culture. Science (Wash DC) 1994;265:1098–1101. doi: 10.1126/science.8066449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes I, Gleizes P-E, Metz CN, Rifkin DB. Latent transforming growth factor-β binding proteins domains involved in activation and transglutaminase-dependent cross-linking of latent transforming growth factor-β. J Cell Biol. 1997;136:1151–1163. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.5.1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oklu R, Metcalfe J, Hesketh T, Kemp P. Loss of consensus heparin binding site by alternative splicing of latent transforming growth factor-β binding protein-1. FEBS Lett. 1998;425:281–285. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00257-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olofsson A, Ichijo H, Moren A, ten Dijke P, Miyazono K, Heldin CH. Efficient association of an amino-terminally extended form of human latent transforming growth factor-β binding protein with the extracellular matrix. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:31294–31297. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.52.31294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Shea KS. Embryonic stem cell models of development. Anat Rec. 1999;257:32–41. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(19990215)257:1<32::AID-AR6>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshima M, Oshima H, Taketo MM. TGF-β receptor type II deficiency results in defects of yolk sac hematopoiesis and vasculogenesis. Dev Biol. 1996;179:297–302. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyamada Y, Komatsu K, Kimura H, Mori M, Oyamada M. Differential regulation of gap junction protein (connexin) genes during cardiomyocitic differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells in vitro. Exp Cell Res. 1996;229:318–326. doi: 10.1006/excr.1996.0377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proetzel G, Pawlowski SA, Wiles MV, Yin M, Boivin GP, Howles PN, Ding J, Ferguson MW, Doetschman T. Transforming growth factor-β3 is required for secondary palate fusion. Nat Genet. 1995;11:409–414. doi: 10.1038/ng1295-409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins J, Gulick J, Sanchez A, Howles P, Doetschman T. Mouse embryonic stem cells express the cardiac myosin heavy chain genes during development in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:11905–11909. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohwedel J, Guan K, Zuschratter W, Jin S, Ahnert-Hilger G, Furst D, Fassler R, Wobus AM. Loss of β1 integrin function results in a retardation of myogenic, but an acceleration of neuronal, differentiation of embryonic stem cells in vitro. Dev Biol. 1998;201:167–184. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohwedel J, Maltsev V, Bober E, Arnold H-H, Hescheler J, Wobus AM. Muscle cell differentiation of embryonic stem cells reflects myogenesis in vivo: developmentally regulated expression of myogenic determination genes and functional expression of ionic currents. Dev Biol. 1994;164:87–101. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez A, Jones WK, Gulick J, Doetschman T, Robbins J. Myosin heavy chain gene expression in mouse embryoid bodies. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:22419–22426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanford PL, Ormsby I, Gittenberger-de Groot AC, Sariola H, Friedman R, Boivin GP, Cardell EL, Doetschman T. TGFβ2 knockout mice have multiple developmental defects that are non-overlapping with other TGFβ knockout phenotypes. Development. 1997;124:2659–2670. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.13.2659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slager HG, Freund E, Buiting AMJ, Feijen A, Mummery CL. Secretion of transforming growth factor-β isoforms by embryonic stem cells: isoform and latency are dependent on direction of differentiation. J Cell Physiol. 1993;156:247–256. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041560205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su J, Muranjan M, Sap J. Receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase alpha activates Src-family kinases and controls integrin-mediated responses in fibroblasts. Curr Biol. 1999;9:505–511. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80234-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taipale J, Saharinen J, Hedman K, Keski-Oja J. Latent transforming growth factor-β1 and its binding protein are components of extracellular matrix microfibrils. J Histochem Cytochem. 1996;44:875–889. doi: 10.1177/44.8.8756760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorsteinsdottir S, Roelen BAJ, Goumans M, Ward-van Oostwaard J, Gaspar AC, Mummery C. Expression of α6A integrin splice variant in developing embryonic stem cell aggregates and correlation with cardiac muscle differentiation. Differentiation. 1999;64:173–184. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.1999.6430173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuji T, Okada F, Yamaguchi K, Nakamura T. Molecular cloning of the large subunit of transforming growth factor type beta masking protein and expression of the mRNA in various rat tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:8835–8839. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.22.8835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vittet D, Buchou T, Schweitzer A, Dejana E, Huber P. Targeted null-mutation in the vascular endothelial-cadherin gene impairs the organization of vascular-like structures in embryoid bodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:6273–6278. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vittet D, Prandini M-H, Berthier R, Schweitzer A, Martin-Sisteron H, Uzan G, Dejana E. Embryonic stem cells differentiate in vitro to endothelial cells through successive maturation steps. Blood. 1996;88:3424–3431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wartenberg M, Gunther J, Hescheler J, Sauer H. The embryoid body as a novel in vitro assay system for antiangiogenic agents. Lab Invest. 1998;78:1301–1314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiles MV. Embryonic stem cell differentiation in vitro. Methods Enzymol. 1995;225:900–918. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(93)25057-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wobus AM, Kaomei G, Shan J, Wellner M-C, Rohwedel J, Guanju J, Fleischmann B, Katus HA, Hescheler J, Franz W-M. Retinoic acid accelerates embryonic stem cell-derived cardiac differentiation and enhances development of ventricular cardiomyocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1997;29:1525–1539. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1997.0433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Castilla LH, Xu X, Li C, Gotey G, Weinstein M, Liu PP, Deng C-X. Angiogenesis defects and mesenchymal apoptosis in mice lacking SMAD5. Development. 1999;126:1571–1580. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.8.1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin WS, Smiley E, Bonadio J. Isolation of novel latent transforming growth factor-β binding protein gene (LTBP-3) J Biol Chem. 1995;270:10147–10160. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.17.10147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanetta L, Marcus SG, Vasile J, Dobryansky M, Cohen H, Eng K, Shamamian P, Mignatti P. Expression of von Willebrand factor, an endothelial cell marker, is up-regulated by angiogenesis factors: a potential method for objective assessment of tumor angiogenesis. Int J Cancer. 2000;85:281–288. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(20000115)85:2<281::aid-ijc21>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang XJ, Tsung H-C, Caen JP, Li XL, Yao Z, Han ZC. Vasculogenesis from embryonic bodies of murine embryonic stem cells transfected by TGF-β1 gene. Endothelium. 1998;6:95–106. doi: 10.3109/10623329809072196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]