Abstract

Mutations in the Wilms' tumor 1 gene, WT1, cause pediatric nephroblastoma and the severe genitourinary disorders of Frasier and Denys-Drash syndromes. High levels of WT1 expression are found in the developing kidney, uterus, and testis—consistent with this finding, the WT1 knockout mouse demonstrates that WT1 is essential for normal genitourinary development. The WT1 gene encodes multiple isoforms of a zinc finger-containing protein by a combination of alternative splicing and alternative translation initiation. The use of an upstream, alternative CUG translation initiation codon specific to mammals results in the production of WT1 protein isoforms with a 68-amino-acid N-terminal extension. To determine the function in vivo of mammal-specific WT1 isoforms containing this extension, gene targeting was employed to introduce a subtle mutation into the WT1 gene. Homozygous mutant mice show a specific absence of the CUG-initiated WT1 isoforms yet develop normally to adulthood and are fertile. Detailed histological analysis revealed normal development of the genitourinary system.

The completion of the human genome sequence revealed a surprisingly low gene number relative to expectations (14, 35), turning the spotlight on posttranscriptional events as a means of generating increased proteome complexity (11). The Wilms' tumor suppressor gene, WT1, can be thought of as a paradigm of this—a single gene gives rise to numerous protein isoforms via posttranscriptional processes. The WT1 gene encodes multiple isoforms of a nuclear protein containing four zinc fingers which acts as a transcription factor and is predicted to have a role in RNA processing (6). The major protein isoforms arise as a result of two alternative splicing events and the use of alternative translation initiation sites (6, 10, 20) which, in combination with RNA editing (32), lead to the production of up to 24 isoforms.

The WT1 gene is deleted or rearranged in some cases of pediatric nephroblastoma (4, 7). Mutations in WT1 also cause Denys-Drash syndrome, characterized by glomerular sclerosis, genitourinary defects, and predisposition to Wilms' tumor (26), and Frasier syndrome, characterized by genitourinary defects and nephropathy without predisposition to Wilms' tumor (2). Consistent with this range of clinical phenotypes, the developing genitourinary system is the major site of WT1 expression (28), although WT1 exhibits a complex pattern of expression in a number of tissues throughout development (1, 37). Mice constitutively lacking WT1 have incomplete diaphragms and show abnormal development of several organs, including the heart, spleen, eyes, and adrenal gland, in addition to a complete absence of kidneys and gonads (12, 17, 23, 34).

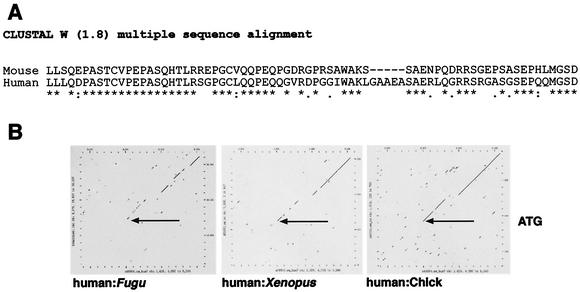

The overall amino acid sequences of WT1 proteins are highly conserved throughout vertebrate evolution (15), and the expression patterns of WT1 are similarly conserved, with high levels of WT1 expression found in the developing genitourinary system, mesothelium, and heart (15). The complexity of WT1 protein isoforms, however, is specific to mammals. All vertebrate WT1 genes can insert three amino acids between zinc fingers 3 and 4, while only mammalian WT1 possesses the 17-amino-acid sequence corresponding to exon 5 and the 68-amino-acid N-terminal extension arising from alternative translation initiation (Fig. 1B) (21). The conserved 3-amino-acid sequence, KTS, arising from an alternative splicing event is essential for WT1 function in genitourinary development. Frasier syndrome patients carry a mutation in one allele of WT1 which disrupts this alternative splicing event such that the overall level of KTS+ WT1 isoforms is reduced (2), and mice constitutively producing only KTS+ or KTS− isoforms display abnormal development of both kidneys and gonads (9).

FIG. 1.

(A) CLUSTAL W alignment of mouse and human WT1 N-terminal extensions originating from the upstream CUG initiator. Stars indicate conserved amino acids. WT1 proteins initiated by the classical AUG initiator begin with the amino acids MGSD. (B) DOTPLOT comparison of the human WT1 genomic region from −250 bp with those of Fugu, Xenopus, and chick. Sequence conservation begins at the ATG in all comparisons. The gap in all three alignments corresponds to the polyproline tract in WT1 exon 1, which is only found in mammals.

WT1 is clearly a fundamental factor in vertebrate kidney and gonad development, given the evolutionary conservation of WT1 splicing and expression in the developing genitourinary system and the absolute requirement of WT1 during genitourinary morphogenesis. However, the genitourinary system has evolved during vertebrate radiation as, intriguingly, has the WT1 gene itself (discussed in references 15 and 21). It is tempting to speculate that the increased complexity of WT1 protein isoforms relates to evolutionary changes within the genitourinary system. The WT1 knockout mouse demonstrates a vital role for WT1 at the early stages of both gonad development and kidney development (17), whereas KTS+ and KTS− mice show advanced stages of nephron formation but display a dramatic gonad phenotype—sex reversal and gonad agenesis, respectively (9). The basic functional unit of the kidney, the nephron, has changed very little throughout vertebrate radiation, although the organization of the kidney and the role it must play have evolved to give the metanephric kidney. This suggests that WT1 in general is essential for kidney development and that the evolutionarily conserved KTS+ and KTS− isoforms play a specific, vital role in the podocyte, a cell type highly conserved throughout evolution. In this context, the mammal-specific WT1 isoforms are unlikely to have a fundamental role in nephrogenesis but may be important for patterning the complex metanephric kidney.

Knocking out WT1, or either of its evolutionarily conserved isoforms, has clearly implicated WT1 in the early stages of gonad development. Due to the embryonic lethality of the WT1 null mutation, little is known regarding the function of WT1 later in reproductive development, in particular in those aspects unique to placental mammals. However, a recent study by Kreidberg et al. found reproductive defects in female heterozygous WT1 null mice on a 129/Sv inbred genetic background (18). Given the significant changes to both the genitourinary system and the repertoire of WT1 proteins during evolution, it will be interesting to determine the function of mammal-specific WT1 isoforms.

The 17-amino-acid sequence corresponding to exon 5 is found only in mammals (15, 21) and has been suggested to contain a transcriptional repression domain that interacts with Par4, a transcriptional regulatory protein (29). However, mice lacking this mammal-specific exon develop normally and both males and females are fertile (24).

A further evolutionary acquisition of WT1 is a 68-amino-acid N-terminal extension arising from an upstream CUG initiator codon. Proteins derived from this initiator have been termed the WT* isoforms (3). WT* isoforms behave similarly to WT1 isoforms derived from the AUG initiator; they are localized to the cell nucleus and are capable of mediating transcriptional repression in reporter assays. Western blot analysis of a range of tissues and cell lines has shown that the WT* isoforms are present in all WT1-expressing tissues and cell lines, including testis, ovary, uterus, kidney, and Wilms' tumor (3, 24). The proportion of total WT1 protein arising from the CUG initiator is difficult to determine precisely given that the affinities of particular antibodies may vary between WT1 isoforms, but estimates suggest that up to 20% of total WT1 protein may posses the N-terminal extension (3; N. D. Hastie and M. Niksic, personal communication). It has been suggested that the role of WT* isoforms may be to modify the activity of WT1 within the cell, possibly by heterodimerization with other WT1 isoforms and/or by interaction with different WT1 cofactors (3). The 68-amino-acid sequences of the N-terminal extensions are 70% identical between mouse and human. Although this is less than the percent conservation of exon 1 between mouse and human, one stretch of 27 amino acids shows 89% identity and may represent a functional unit, such as a factor binding domain (Fig. 1A). Comparing synonymous (KS) with nonsynonymous (KA) substitution rates reveals that the WT1 N-terminal extension has been under purifying selection (KA/KS = 0.433) for the last ∼100 million years. Such analyses show that for the entire coding sequence of the WT1 gene, the KA/KS ratio is 0.051, reflecting the fact that the gene has been under purifying selection throughout vertebrate radiation.

Alternative translation initiation is not a unique feature of the WT1 gene. The Pim-1 proto-oncogene (31) and the fibroblast growth factor 2 (16), antiapoptotic Bag-1 (25), and vascular endothelial growth factor (13) genes all utilize alternative, upstream CUG initiator codons to generate larger protein isoforms. The functional significance of these larger isoforms is not clear; however, it is interesting that fibroblast growth factor 2, Bag-1, and vascular endothelial growth factor isoforms initiated by the alternative CUG codon display altered subcellular localization compared with their respective AUG-initiated counterparts.

To determine the function of WT* isoforms during mammalian development, we performed gene targeting to create mice lacking WT* isoforms. Surprisingly, homozygous mice lacking WT* isoforms develop normally and are fertile.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Design and production of targeting vector.

Amino acid comparisons were performed by using CLUSTAL W alignments (34). Mouse-human genomic DNA comparisons for the positioning of the selectable marker (the residual loxP site) were performed with DOTTER (33).

Synthetic oligonucleotide linkers were utilized to introduce the STOP/PstI modification into a 430-bp PmlI restriction fragment encompassing the CUG initiator. This fragment was sequence verified and cloned into pPolyB6. pPolyB6 consists of a 6-kb BglII genomic DNA fragment encompassing exon 1 of WT1 with ∼2.5 kb of upstream sequence and ∼1.5 kb of downstream sequence (a kind gift of Jordan Kreidberg) cloned into the pPolyIII vector. The floxed cytomegalovirus-driven hygromycin-herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase (hygromycin-HSVtk) fusion gene (kind gift of Julia Dorin) was isolated as a blunt-ended HindIII fragment and cloned into an EcoRV restriction site within a nonconserved region of intron 1. The targeting vector was isolated from plasmid sequences by NotI restriction digestion followed by gel purification.

Production of WT*-deficient mice.

One hundred micrograms of gel-purified targeting vector was electroporated into 2 × 107 embryonic day 14 [E14(iv)] embryonic stem (ES) cells (kind gift of Austin Smith). One hundred twenty hygromycin-resistant clones were analyzed by Southern blotting (30) by using the external probe 1 to hybridize PstI-restricted genomic DNA. Fourteen clones were found to contain a correctly targeted WT1 allele. Seven of these clones were analyzed by Southern blotting for the presence of the STOP/PstI modification. Hybridizing PstI-restricted genomic DNA with the internal probe 2 demonstrated that four of the seven correctly targeted clones contained the modification, i.e., in three of the targeted clones analyzed, the recombination complex must have resolved downstream of the modification.

Two correctly targeted clones harboring the STOP/PstI modification were transiently transfected with 50 μg of pMC1-Cre. All of the 20 ganciclovir-resistant colonies selected for Southern blot analysis showed complete excision of the hygromycin-HSVtk fusion gene due to Cre-mediated loxP recombination. Karyotypically normal clones were injected into C57BL/6 blastocysts (5), and chimeric male mice were crossed with C57BL/6 females to obtain germ line transmission of the modified allele. Heterozygous mice were maintained by backcrossing to C57BL/6 and homozygous mice generated by intercrossing heterozygotes. Wild-type, heterozygous, and homozygous mice were obtained from heterozygous intercrosses at normal Mendelian ratios. To test the fertility of homozygous WT*-deficient animals, 10 homozygous male mice were crossed with CD1 female mice and 10 homozygous female mice were crossed with CD1 male mice.

RNA and protein analysis.

Nuclear extracts from fetal kidneys and fetal testes were prepared from freshly isolated tissues as described previously (19), separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) on 10% polyacrylamide gels, blotted, and probed with either anti-WT1 polyclonal antibody (C19; Santa Cruz) or anti-WT1 monoclonal antibody (H2; Dako) as described previously (19).

Total RNA was isolated from freshly isolated fetal tissues by using the RNAgents isolation system (Promega) and then subjected to DNAse I treatment (Roche Diagnostics) and a second phenol-chloroform extraction and precipitation. Total RNA was reverse transcribed by using an oligo(dT) primer followed by PCR with oligonucleotides specific for either alternative splicing event of WT1 (all oligonucleotide sequences are available on request).

Histology.

Freshly isolated tissues from ∼3-month-old homozygous mutant animals and wild-type littermates were fixed overnight in 10% neutral buffered saline at 4°C and dehydrated through increasing concentrations of ethanol. Paraffin-embedded sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

RESULTS

Strategy for elimination of WT* isoforms.

To specifically inhibit CUG-initiated WT1 translation, a targeting vector was designed to introduce a translation stop signal 12 amino acids downstream of the CUG initiator (Fig. 2A). This mutation is similar to that created by Bruening and Pelletier, resulting in an absence of WT* isoforms but not affecting translation from the classical AUG start codon (3). A PstI restriction site was introduced adjacent to the stop codon to facilitate the detection of the mutant allele in ES cells and mice. The creation of this PstI restriction site also introduces a reading frame shift such that any translational “read through” of the stop codon would not generate WT* isoforms.

FIG. 2.

Gene targeting strategy for elimination of WT* isoforms. (A) Diagram of WT1 genomic region around exon 1. P, PstI; R, EcoRV; Probe 2, internal ∼500-bp XhoI-EcoRI segment; Probe 1, external ∼800-bp XbaI-PstI segment. (B) Targeting vector. HYGRO-tk, hygromycin-HSVtk fusion gene. (C) Final targeted WT1 allele present in ES cells and mice. (D) DOTPLOT comparison of human and mouse WT1 intron 1 sequences showing the position of the residual loxP site.

A two-step strategy using Cre-mediated loxP recombination was employed to allow the removal of the selectable marker cassette from ES cells prior to generating transgenic mice. This strategy also ensured that minimal modifications would be made to the mutated WT1 allele so as not to affect normal expression and translation of WT1 isoforms from the AUG initiator. A loxP-flanked hygromycin-HSVtk fusion gene was placed downstream of exon 1 of the WT1 gene. After positive selection and clone identification, Cre treatment and negative selection gave clones in which a single, residual loxP site remained within exon 1. As this exogenous 34-bp sequence could potentially disrupt regulatory sequences located within the intron, DNA sequence comparison was undertaken to identify a suitable position for the remaining loxP site. Comparison of mouse and human intron 1 sequences showed several highly conserved regions which may possess an as yet unknown regulatory function. The selectable marker was placed in a region of the intron not conserved between mouse and human (Fig. 2B). In addition, the mouse sequence showed a small deletion in this region relative to the human sequence, strongly suggesting that to leave a 34-bp loxP site at this position would have no deleterious effect on WT1 expression.

Generation of homozygous mutant mice.

The targeting vector (Fig. 2A) was electroporated into E14 ES cells. Hygromycin-resistant clones containing the STOP/PstI modification were identified by Southern blotting of PstI-restricted genomic DNA with the external probe (probe 1) and an internal probe (probe 2).

Karyotypically normal clones containing the correctly targeted STOP/PstI modification were transiently transfected with pMC-Cre, and ganciclovir-resistant colonies were tested by Southern blotting for Cre-mediated excision of the hygromycin-HSVtk fusion cassette. One karyotypically normal clone that underwent Cre-mediated excision of the selectable marker was used to create germ line-transmitting chimeric mice.

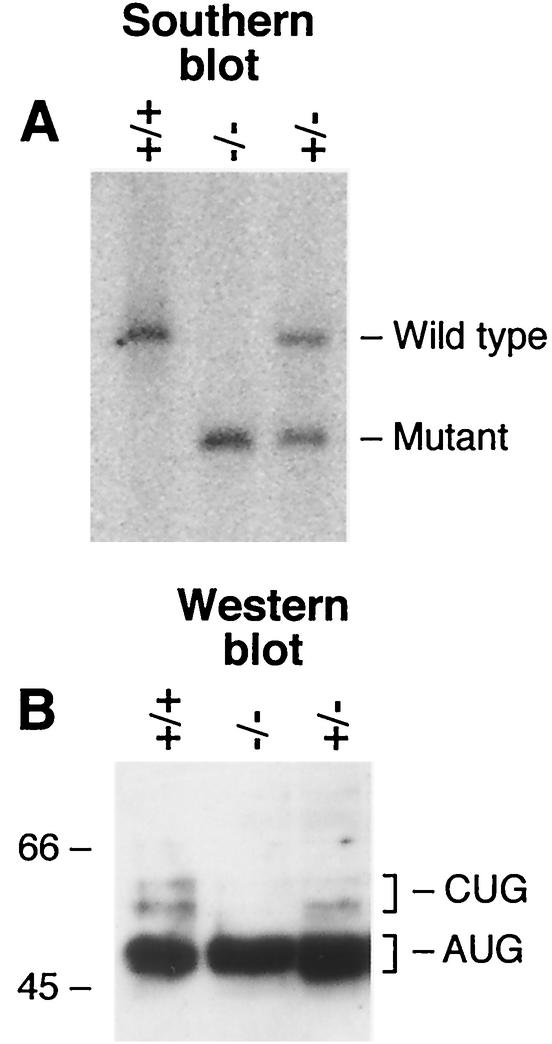

Mice heterozygous for the mutation were intercrossed, giving rise to normal Mendelian ratios of wild-type, heterozygous, and homozygous offspring as determined by Southern blot analysis (Fig. 3A). Homozygous mutant animals were observed to be viable and healthy at up to 1 year of age.

FIG. 3.

Creation of mice lacking WT* isoforms. (A) Southern blot of PstI-restricted tail DNA derived from heterozygous intercross showing results for wild-type (+/+), heterozygous mutant (+/−), and homozygous mutant (−/−) littermates. Southern blotting was performed with probe 2. (B) Western blot of fetal kidney nuclear protein separated by SDS-PAGE on a 10% polyacrylamide gel and probed with anti-WT1 monoclonal antibody H2. 66-kDa and 45-kDa size markers are indicated.

Molecular analysis of mutant mice.

To verify that the STOP/PstI modification had specifically eliminated WT* isoforms and that expression and translation from the AUG initiator were unaffected, Western blot analysis was performed on fetal (E16.5) kidney nuclear extracts from wild-type, heterozygous, and homozygous mutant mice by using the WT1 monoclonal antibody H2 (Fig. 3B). WT1 proteins of 47 to 49 kDa, as well as the 54- to 56-kDa WT* isoforms, are present in wild-type fetal kidney. The WT* isoforms appear as a doublet corresponding to the presence or absence of the alternatively spliced exon 5, while the AUG-initiated isoforms alternatively spliced for exon 5 comigrate on this SDS-PAGE gel. No WT* isoforms of 54 to 56 kDa are present in homozygous fetal kidney (or homozygous fetal testis, not shown), demonstrating that the STOP/PstI mutation was preventing translation of these isoforms. Heterozygous mutants have reduced levels of WT* isoforms, while WT1 protein originating from the AUG is produced at normal levels in mice of each genotype (Fig. 3B).

Mutant mice are healthy and fertile.

WT1 plays a crucial role in the development of both kidneys and gonads, is involved in sex determination, and is expressed in Sertoli cells of the testis and granulosa cells of the ovary, oviduct, uterus, and mammary gland (1, 27, 28, 37). To investigate whether the mammal-specific WT* isoforms are involved in mammalian reproduction, groups of 10 mutant mice were test mated. Normal-sized litters were obtained with both male and female homozygous mutant mice, with homozygous males giving an average litter size of 10.2 (±4.7; n = 10) and homozygous females producing an average litter size of 8.3 (±4.6; n = 10). The observation that homozygous mutant females nursed their offspring to weaning age indicates that the WT* isoforms are not essential for lactation.

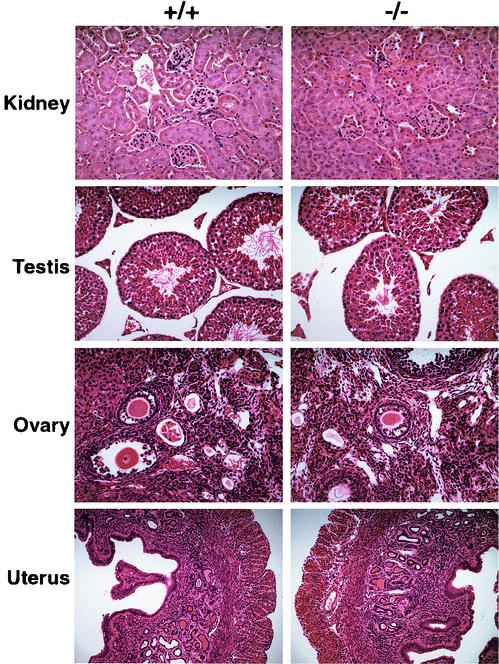

Histological analysis was performed on tissues isolated from adult homozygous mutant mice and wild-type littermates to look for any subtle effect of the elimination of WT* isoforms on the development of WT1-expressing tissues. Figure 4 shows hematoxylin- and eosin-stained kidney, testis, ovary, and uterus sections in which there are no discernible differences between wild-type and homozygous mutant tissues, demonstrating that, in the absence of these specific isoforms, there are no histological changes to the organs in which WT1 is known to be expressed.

FIG. 4.

Hematoxylin- and eosin-stained sections of wild type (+/+) and homozygous mutant (−/−) kidney, testis, ovary, and uterus from ∼3-month-old littermates. Kidney, testis, and ovary, 20× objective; uterus, 10× objective.

DISCUSSION

This paper describes the generation of mice lacking the mammal-specific WT* protein isoforms and demonstrates that these isoforms are not essential for normal development or reproduction. These findings are similar to those of Natoli et al., who created normal, healthy mice lacking the mammal-specific 17-amino-acid sequence corresponding to exon 5 of WT1 (24).

A surprising finding from the completion of the human genome sequence was that humans possess fewer genes than previous estimates for mammals (14, 35). Recent suggestions that the majority of human genes can give rise to numerous protein isoforms by alternative splicing and/or alternative translation initiation have provided a means by which the proteome can potentially possess the complexity assumed to be necessary for the development of a mammal (22). In this way, WT1 can be seen as a paradigm—a gene conserved throughout vertebrate radiation and expressed in a highly evolving organ system in all vertebrates which produces numerous mammal-specific protein isoforms, at least some of which exhibit specific properties in in vitro transfection assays. However, this study and the recent results from Natoli et al. provide a cautionary note that the complexity of mammals cannot be solely explained through the possession of a complex proteome.

Why the mammalian WT1 gene produces numerous protein isoforms, however, remains enigmatic. Gene targeting in the mouse has demonstrated a fundamental role for WT1 during mammalian development (17) and has subsequently been refined to show that the 3-amino-acid sequence produced by an alternative splicing event common to all vertebrates is essential for normal genitourinary development (9). Significantly, elimination of either KTS+ or KTS− isoforms has dramatic consequences for development. The demonstration that both WT* isoforms and those containing the amino acid sequence corresponding to exon 5 are dispensable for mammalian development suggests that the evolution of the WT1 gene has not been the driving force for mammalian genitourinary evolution per se. However, the fact that the KA/KS ratio is 0.433 for the N-terminal extension shows that there has been selection at the amino acid level for this domain. It may be that these evolutionary acquisitions by WT1 are involved in a pathway which has evolved and, as suggested by Natoli et al., that WT* isoforms (and those containing the sequence corresponding to exon 5) modify the action of WT1 in a subtle way which could be exposed by careful gene expression profiling of tissues from these mutant mice (24).

In order to seek subtle changes, for example, through a gene expression profile, it will be necessary to breed this mutation (and that described by Natoli et al.) into a range of inbred mouse strains to eliminate “hybrid vigor” and allow precise comparisons of gene expression levels between mutant and wild-type mice. In this regard, it is interesting that the phenotypes of WT1 null mutant mice show a range of severity depending upon genetic background—some homozygous WT1 null mice survive until birth on an outbred genetic background, while C57BL/6 inbred WT1 null mice die at around 13 days of gestation (12, 17), and 129/Sv inbred WT1 heterozygous null female mice have small ovaries and are infertile, while outbred heterozygous females display normal reproduction (18). In addition, a recent study has shown that up to 25% of mice with reduced levels of WT1 expression succumb to a fatal glomerulosclerosis within 6 months of birth (8). WT*-deficient mice show no overt mutant phenotype at up to 1 year of age, although, as with other WT1-associated phenotypes, it will be necessary to study WT*-deficient mice on a number of pure genetic backgrounds to determine if they display a subtle mutant kidney phenotype.

Finally, the generation of ES cells harboring the WT* STOP/PstI mutation allows, in combination with exon 5 deletion, for the creation of doubly targeted ES cells from which mice deficient in all major mammal-specific WT1 isoforms can be derived. Given that both WT1 and the tissues in which it is expressed have evolved, this experiment could shed light on the continuing enigma of why the mammalian WT1 gene produces so many different protein isoforms. It may be that WT* isoforms and those containing the sequence corresponding to exon 5 have coevolved, and perhaps these two sets of isoforms perform a mammal-specific yet redundant function.

Acknowledgments

We thank Julia Dorin, Sheila Webb, and Fiona Kilanowski for advice and help with ES culture and blastocyst injection and Colin Semple for his expert assistance with bioinformatics. E14(iv) ES cells were a kind gift from Austin Smith. Jordan Kreidberg kindly provided pBgl6, and we are grateful to Orit Lustig-Yariv and Shirley Smith for helpful discussions and comments.

This work was funded by the Medical Research Council (United Kingdom), and C.G.M. was in receipt of an MRC Research (Training) Fellowship.

REFERENCES

- 1.Armstrong, J. F., K. Pritchard-Jones, W. A. Bickmore, N. D. Hastie, and J. B. Bard. 1993. The expression of the Wilms' tumour gene, WT1, in the developing mammalian embryo. Mech. Dev. 40:85-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barbaux, S., P. Niaudet, M. C. Gubler, J. P. Grunfeld, F. Jaubert, F. Kuttenn, C. N. Fekente, T. N. Souleyreau, E. Thibaud, M. Fellous, and K. McElreavey. 1997. Donor splice site mutations in WT1 are responsible for Frasier syndrome. Nat. Genet. 17:467-470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bruening, W., and J. Pelletier. 1996. A non-AUG translation initiation event generates novel WT1 isoforms. J. Biol. Chem. 271:8646-8654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Call, K. M., T. Glaser, C. Y. Ito, A. J. Buckler, J. Pelletier, D. A. Haber, E. A. Rose, A. Kral, H. Yeger, and W. H. Lewis. 1990. Isolation and characterization of a zinc finger polypeptide gene at the human chromosome 11 Wilms' tumor locus. Cell 60:509-520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dorin, J. R., P. Dickinson, E. W. Alton, S. N. Smith, D. M. Geddes, B. J. Stevenson, W. L. Kimber, S. Fleming, A. R. Clarke, M. L. Hooper, et al. 1992. Cystic fibrosis in the mouse by targeted-insertional mutagenesis. Nature 359:211-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Englert, C. 1998. WT1—more than a transcription factor? Trends Biochem. Sci. 23:389-393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gessler, M., A. Poustka, W. Cavenee, R. L. Neve, S. H. Orkin, and G. A. Bruns. 1990. Homozygous deletion in Wilms tumours of a zinc-finger gene identified by chromosome jumping. Nature 343:774-778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gou, J.-K., A. L. Menke, M.-C. Gubler, A. R. Clarke, D. Harrison, A. Hammes, N. D. Hastie, and A. Schedl. 2002. WT1 is a key regulator of podocyte function: reduced expression levels cause crescentic glomerulonephritis and mesangial sclerosis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 11:651-659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hammes, A., J. K. Gou, G. Lutsch, J. R. Leheste, D. Landrock, U. Ziegler, M. C. Gubler, and A. Schedl. 2001. Two splice variants of the Wilms' tumor 1 gene have distinct functions during sex determination and nephron formation. Cell 106:319-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hastie, N. D. 1994. Wilms' tumour: a case of disrupted development. Annu. Rev. Genet. 28:523-558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hastie, N. D. 2001. Life, sex, and WT1 isoforms—three amino acids can make all the difference. Cell 106:391-394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herzer, U., A. Crocoll, D. Barton, N. Howells, and C. Englert. 1999. The Wilms tumor suppressor gene wt1 is required for development of the spleen. Curr. Biol. 9:837-840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huez, I., S. Bornes, D. Bresson, L. Creancier, and H. Prats. 2001. New vascular endothelial growth factor isoforms generated by internal ribosome entry site-driven CUG translation initiation. Mol. Endocrinol. 15:2197-2210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium. 2001. The sequence of the human genome. Nature 409:860-921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kent, J., A. M. Coriat, P. T. Sharpe, N. D. Hastie, and V. van Heyningen. 1995. The evolution of WT1 sequence and expression pattern in the vertebrates. Oncogene 11:1781-1792. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kevil, C., P. Carter, B. Hu, and A. DeBenedetti. 1995. Translational enhancement of FGF-2 by eIF-4 factors, and alternative utilization of CUG and AUG codons for translation initiation. Oncogene 11:2339-2348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kreidberg, J. A., H. Sariola, J. M. Loring, M. Maeda, J. Pelletier, D. Housman, and R. Jaenisch. 1993. WT-1 is required for early kidney development. Cell 74:679-691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kreidberg, J. A., T. A. Natoli, L. McGinnis, M. Donovan, J. D. Biggers, and A. Amstutz. 1999. Coordinate action of Wt1 and a modifier gene supports embryonic survival in the oviduct. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 52:366-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ladomery, M. R., J. Slight, S. McGhee, and N. D. Hastie. 1999. Presence of WT1, the Wilm's tumor suppressor gene product, in nuclear poly(A)(+) ribonucleoprotein. J. Biol. Chem. 274:36520-36526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee, S. B., and D. A. Haber. 2001. Wilms tumor and the WT1 gene. Exp. Cell Res. 264:74-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miles, C., G. Elgar, E. Coles, D. J. Kleinjan, V. van Heyningen, and N. D. Hastie. 1998. Complete sequencing of the Fugu WAGR region from WT1 to PAX6: dramatic compaction and conservation of synteny with human chromosome 11p13. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:13068-13072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Modrek, B., and C. Lee. 2002. A genomic view of alternative splicing. Nat. Genet. 30:13-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moore, A. W., L. McInnes, J. Kreidberg, N. D. Hastie, and A. Schedl. 1999. YAC complementation shows a requirement for Wt1 in the development of the epicardium, adrenal gland and throughout nephrogenesis. Development 126:1845-1857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Natoli, T. A., A. McDonald, J. A. Alberta, M. E. Taglienti, D. E. Housman, and J. A. Kreidberg. 2002. A mammal-specific exon of WT1 is not required for development or fertility. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:4433-4438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Packham, G., M. Brimmell, and J. L. Cleveland. 1997. Mammalian cells express two differently localized Bag-1 isoforms generated by alternative translation initiation. Biochem. J. 328:807-813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pelletier, J., W. Bruening, C. E. Kashtan, S. M. Mauer, J. C. Manivel, J. E. Striegel, D. C. Houghton, C. Junien, R. Habib, L. Fouser, et al. 1991. Germline mutations in the Wilms' tumor suppressor gene are associated with abnormal urogenital development in Denys-Drash syndrome. Cell 67:437-447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pelletier, J., M. Schalling, A. J. Buckler, A. Rogers, D. A. Haber, and D. Housman. 1991. Expression of the Wilms' tumor gene WT1 in the murine urogenital system. Genes Dev. 5:1345-1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pritchard-Jones, K., S. Fleming, D. Davidson, W. Bickmore, D. Porteous, C. Gosden, J. Bard, A. Buckler, J. Pelletier, D. Housman, V. van Heyningen, and N. Hastie. 1990. The candidate Wilms' tumour gene is involved in genitourinary development. Nature 346:194-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Richard, D. J., V. Schumacker, B. Royer-Pakora, and S. G. Roberts. 2001. Par4 is a coactivator for a splice isoform specific transcriptional activation domain in WT1. Genes Dev. 15:328-339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 31.Saris, C. J., J. Domen, and A. Berns. 1991. The pim-1 oncogene encodes two related protein-serine/threonine kinases by alternative initiation at AUG and CUG. EMBO J. 10:655-664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sharma, P. M., M. Bowman, S. L. Madden, F. J. Rauscher III, and S. Sukumar. 1994. RNA editing in the Wilms' tumor susceptibility gene, WT1. Genes Dev. 8:720-731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sonnhammer, E. L., and R. Durbin. 1995. A dot-matrix program with dynamic threshold control suited for genomic DNA and protein sequence analysis. Gene 167:GC1-GC10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thompson, J. D., D. G. Higgins, and T. J. Gibson. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:4673-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Venter, J. C., M. D. Adams, E. W. Myers, P. W. Li, R. J. Mural, G. G. Sutton, H. O. Smith, M. Yandell, C. A. Evans, R. A. Holt, et al. 2001. The sequence of the human genome. Science 291:1304-1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wagner, K. D., N. Wagner, V. P. Vidal, G. Schley, D. Wilhelm, A. Schedl, C. Englert, and H. Scholz. 2002. The Wilms' tumor gene Wt1 is required for normal development of the retina. EMBO J. 21:1398-1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou, J., F. J. Rauscher III, and C. Bondy. 1993. Wilms' tumor (WT1) gene expression in rat decidual differentiation. Differentiation 54:109-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]