Abstract

Telomerase, the enzyme that maintains the ends of chromosomes, is absent from the majority of somatic cells but is present and active in most tumours. The gene for the reverse transcriptase component of telomerase (hTERT) has recently been identified. A cDNA clone of this gene was used as a probe to identify three genomic bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) clones, one of which was used as a probe to map hTERT by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) to chromosome 5p15.33. This BAC probe was further used to look at copy number of the hTERT region in immortal cell lines. We found that 10/15 immortal cell lines had a modal copy number of 3 or more per cell, with one cell line (CaSki) having a modal copy number of 11. This suggests that increases in copy number of the hTERT gene region do occur, and may well be one route to upregulating telomerase levels in tumour cells. 5p15 gains and amplifications have been documented for various tumour types, including non-small cell lung carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma of head and neck, and uterine cervix cancer, making hTERT a potential target.

Keywords: telomerase, hTERT, reverse transcriptase, gene mapping, telomerase protein component

Introduction

In the absence of the enzyme telomerase, the ends of a chromosome shorten every time a cell divides and this is thought to limit the proliferative life span of a cell, as when the telomeres become too short, the cells enter a state of permanent cell cycle arrest, termed senescence [1]. Telomerase is a ribonucleoprotein complex capable of adding DNA repeats to the ends of chromosomes thus maintaining telomere length. Presence of telomerase has been shown to be widespread during human development [2,3] but in adult tissues, its activity is restricted to the male germ cells, and, at lower levels, in activated lymphocytes and stem cells of regenerating tissues [4–7]. However, high levels of telomerase activity have been detected in the majority of immortal cell lines and human cancers [8], suggesting that presence of active telomerase confers immortality on these cells, and may even be necessary to overcome senescence.

The essential components of the telomerase enzyme have been shown to be the RNA template subunit, hTR [9], and the reverse transcriptase catalytic subunit, hTERT [10,11], with telomerase activity having been reconstituted in vitro by the addition of these two components to reticulocyte extract [12]. However, it has now been shown that the molecular chaperones p23 and Hsp90, present in the extract, are also required for activity [13].

hTERT has previously been tentatively mapped to the distal portion of chromosome 5p by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis of two radiation hybrid panels [10]. We wished to obtain a hTERT probe suitable for fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) as this would allow direct physical mapping of the gene. In addition, such a probe would be a useful tool for investigating hTERT copy number in cell lines and tumours, as over-representation and amplification of 5p and sub-regions of 5p have been documented for several tumour types [14].

Materials and Methods

Isolation of a hTERT Probe

3.5 µg of PGRN145 DNA (a plasmid containing the hTERT cDNA, kindly provided by the Geron Corporation) was digested with EcoRI in the appropriate buffer (Gibco BRL) to release the cDNA insert. The 3454-bp insert was electrophoretically separated from the vector on a 1% agarose gel, and purified using the QIAquick gel extraction kit (QIAGEN) following manufacturer's instructions. The CalTech human bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) library (release IV) (Research Genetics Inc., http://www.resgen.com) and the RPCI-11 human BAC library (Roswell Park Cancer Institute, http://bacpac.med.buffalo.edu) were then screened by hybridization using this 3454-bp hTERT cDNA as a probe (screening service provided by Research Genetics Inc.). This identified three BACs from the RPCI-11 library: 124I24, 518C13, and 600M8. BAC DNA was isolated using a scaled-up version of an alkaline lysis protocol (available on the Roswell Park Cancer Institute website [15]). Presence of the hTERT gene was confirmed by PCR amplification of 348 bp of the promoter; forward primer: 5′-GCGCTCGAGTCGCTGGCGTCCCTGCACCC-3′, reverse primer: 5′-CGCAAGCTTGCAGCGCTGCCTGAAACTCG-3′ (position-394 to -47, where position 1 is the first base of the coding sequence, ATG); the Advantage-GC Genomic system (Clontech) was used, with the following cycling conditions: 95°C 1 minute, followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 seconds and 68°C for 3 minutes, with a final 3-minute step at 68°C. PCR products were checked on a 2% agarose gel, then purified using the QIAquick PCR purification kit (QIAGEN). Products were then subjected to Big Dye Terminator sequencing on an ABI 373A using the original PCR primers. Sequence was compared to that published for the hTERT promoter [16] using MegAlign and SeqMan computer software (DNAS-TAR Inc.). The three BACs were digested with EcoRI and the restriction patterns found to be very similar, indicating a large degree of overlap among the three clones. Therefore, just one (518C13) was used as a probe.

Mapping of hTERT by FISH

518C13 DNA was labeled using a biotin-nick translation mix (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) following manufacturer's protocol. Probe-specificity was confirmed by hybridization to lymphocyte metaphase spreads in combination with total chromosome 5 COATASOME® probe (Appligene Oncor) following manufacturer's protocol. Additional probes used in conjunction with 518C13 for mapping were a digoxigenin-labeled 5p15.2-specific probe (D5S23, Appligene Oncor), and a digoxigenin-labeled 5p subtelomeric probe (Cytocell, Chromoprobe T 5ptel supplied on coverslip, cosmid 114j18, hybridizes within 300 kb of the terminal end of the p-arm of the chromosome). Manufacturers' protocols were followed, except that instead of 10 µ 5p15.2 probe mix, 8 µl was used with the addition of 4 µl biotin-labeled 518C13; and instead of 10 µl Cytocell hybridization buffer (for the 5p subtelomeric probe), 5 µl was used with the addition of 5 µl biotin-labeled 518C13. The 5p15.33 chromosomal localisation for hTERT was confirmed using digitised images (Vysis, UK) to enhance the DAPI banding patterns of chromosomes in the 550 to 750 band range [17].

hTERT Copy Number in Cell Lines

Metaphase spreads were made for the 16 cell lines listed in Table 1 using standard protocols. 518C13 DNA was labeled with Spectrum Green™ using a nick translation kit (Vysis, UK) and hybridization and visualisation were carried out as described previously [18] using the Hybaid Omnislide system. Between 13 and 57 metaphases were counted per cell line to allow quantitation of copy number.

Table 1.

hTERT Copy Number in a Panel of Cell Lines and Normal Lymphocytes.

| Cell line | Origin | hTERT copies per cell | No. of metaphases | Modal hTERT copy number* |

| C33A | Cervical carcinoma | 2 | 31 | 2 |

| CaSki | Cervical carcinoma | 9 | 17 | 11 |

| 10 | 17 | |||

| 11 | 23 | |||

| ME180 | Cervical carcinoma | 4 | 31 | 4 |

| SiHa | Cervical carcinoma | 6 | 12 | 8 (1 iso) |

| 7 | 8 | |||

| 8 | 23 | |||

| HeLa | Cervical adenocarcinoma | 8 | 7 | 8 (3 iso) |

| 9 | 3 | |||

| 10 | 3 | |||

| A549 | Lung carcinoma | 2 | 9 | 3 |

| 3 | 35 | |||

| GLC4 | Lung carcinoma (small cell) | 3 | 21 | 3 |

| LDAN | Lung carcinoma | 2 | 25 | 2 |

| 3 | 5 | |||

| Calu-3 | Lung adenocarcinoma | 6 | 22 | 6 |

| 8 | 2 | |||

| H125 | Lung adenocarcinoma | 2 | 5 | 5 |

| 3 | 14 | |||

| 4 | 15 | |||

| 5 | 20 | |||

| 5637 | Bladder carcinoma | 3 | 30 | 3 |

| 4 | 8 | |||

| MCF7 | Breast adenocarcinoma | 2 | 30 | 2 |

| COLO320 | Colorectal adenocarcinoma | 2 | 30 | 2 |

| A2780 | Ovarian adenocarcinoma | 2 | 32 | 2 |

| A431 | Squamous carcinoma | 3 | 30 | 3 |

| W138 | Foetal lung fibroblasts (mortal) | 2 | 31 | 2 |

| - | Normal lymphocytes | 2 | 30 | 2 |

iso = 5p isochromosomes.

Results

Isolation of a hTERT Probe

To map hTERT with certainty, we required a probe suitable for FISH experiments. A hTERT genomic clone was obtained by screening the RPCI-11 BAC library by hybridization with the hTERT cDNA. Three BAC clones (124I24, 518C13, and 600M8) all hybridized strongly to the hTERT cDNA, and presence of the gene was confirmed by PCR-amplification and sequencing of a 348-bp region of the promoter. Restriction digestion demonstrated a large degree of overlap among the three BAC clones; therefore, just one (518C13) was used as a probe for FISH studies. The efficiency of the probe was greater than 95% (30 metaphase spreads) when hybridized to normal lymphocytes. A probe with high hybridization efficiency is necessary for accurate mapping by FISH and is essential for quantitative analysis of gene copy number [18].

Mapping of hTERT by FISH

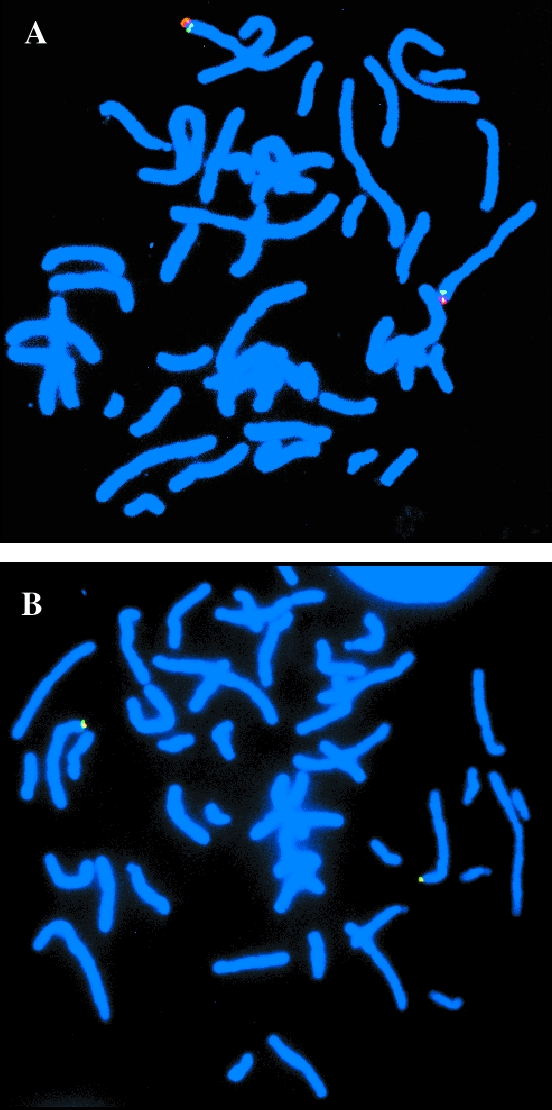

hTERT probe 518C13 was hybridized to metaphase spreads either alone, or in conjunction with a second chromosome 5-specific probe. Figure 1A shows the hybridization of 518C13 together with a probe specific for 5p15.2 (D5S23), clearly demonstrating that hTERT is positioned distally to 5p15.2. In Figure 1B, the signal from the hTERT probe is seen to overlap with that from a 5p subtelomeric probe. This subtelomeric probe (Cytocell) is stated to hybridize within 300 kb of the telomeric end of the p-arm of chromosome 5, indicating that hTERT also lies very close to the chromosome tip, within the 5p15.33 chromosomal band. The 5p15.33 chromosomal localisation for hTERT was confirmed using digitised images to enhance chromosome DAPI banding pattern (data not shown) [17]. Interestingly, deletions in this region of chromosome 5p are associated with the Cri Du Chat Syndrome, which is characterised by growth failure, microcephaly, facial abnormalities and severe retardation, (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/guide/HsChr5.shtml). Our hTERT probe may therefore be of value in defining the genes clustering to this region and refining deletion boundaries. This region of chromosome 5 is as yet poorly characterised and few genes have been placed in the telomeric region (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/guide/HsChr5.shtml). Indeed, the accurate physical mapping of hTERT in this study may place hTERT as the most distal gene on chromosome 5p mapped to date, (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genemap/map.cgi?BIN=163&MAP=GB4).

Figure 1.

Localization of hTERT to cliromosome 5p15.33. (A) Double hybridization of the BAC probe for hTERT (red), and chromosome 5p15.2 reference probe (green). (B) Double hybridization of the BAC probe for hTERT (red), and the chromosome 5p sub-telomeric reference probe (green), showing that these signals are co-incident.

hTERT Copy Number in Cell Lines

The 518C13 BAC probe was then used to determine the copy number of the hTERT gene in 15 cancer cell lines (Table 1). 10 of the 15 immortal lines possessed a modal copy number of 3 or more, with one cervical carcinoma-derived cell line (CaSki) having 11 copies per cell. Isochromosomes of 5p were seen in two cervical tumour-derived cell lines (HeLa and SiHa). No increases were found in a normal mortal cell line (WI38) or in normal lymphocytes.

Discussion

The mapping of the hTERT gene to the subtelomeric band 5p15.33 is interesting with regard to possible regulatory mechanisms. One could speculate that its proximity to the telomeric heterochromatin and associated proteins may affect gene activity. For example, in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, proximity to the telomeres causes genes to be repressed through the telomere position effect [19]. In addition, Wright and Shay have proposed that senescence-associated genes in mammalian cells may also be regulated through their proximity to subtelomeric heterochromatin [20]. Thus, it would be of interest to test whether telomere shortening directly influences hTERT activity.

Certainly, the localisation of hTERT to 5p15.33 is interesting with regard to amplified and over-represented regions of the genome previously identified by comparative genomic hybridization in various tumour types (see Ref. [14] for a review). 5p15, and more specifically 5p15.3, has been found at increased numbers in such tumours as uterine cervix cancer [21], non-small cell lung carcinoma [22], squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck [23–26], as well as malignant fibrous histiocytoma of soft tissue [27,28], and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours [29]. In the limited selection of cell lines analyzed in this study, no discrete amplification of the hTERT region was observed, however, increased copy number was common, with 5p isochromosomes seen in 2 cell lines (HeLa and SiHa). No copy number alterations were observed in the WI38 normal mortal cell line. Increasing the copy number of hTERT in cancer cells may titrate out repressors, or compensate for low levels of transcriptional activators, thus allowing a tumour to increase the levels of the catalytic subunit of telomerase. Further investigations will be required to determine if hTERT is an important gene amplified in these tumours or whether a nearby region was commonly amplified, which did not include hTERT, thereby excluding it as the target gene [30].

Both hTERT and the telomerase RNA component, hTR, are required for telomerase activity and expression of both is upregulated in cancer cells [10,31,32]. Interestingly, many of the tumour types that show increases at 5p15 also show gains at 3q26, the region to which hTR has been mapped [30]. Over-representation of 3q26 has been demonstrated for uterine cervix cancer [21], squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck [25,26,33,34], small cell and non-small cell lung carcinoma [22,35–39]. We previously demonstrated that hTR was involved in this region of amplification [30], and a recent study has narrowed down the region for lung and cervix tumours to 1 to 2 Mb centered around hTR, further supporting it as a potential target [40]. These gains in both 3q26 and 5p15 are potentially interesting given the presence of the hTR and hTERT genes. Thus, it is of interest to determine whether both gains occur in the same tumours, or whether they occur independently.

In conclusion, the development of FISH probes for both hTR [30] and hTERT (this study) may prove useful in determining whether copy number gains of these genes are important in the reactivation of telomerase during tumour progression. In addition, the mapping of hTERT to the telomeric tip of chromosome 5p may be relevant to the regulation of hTERT expression by chromatin structure and telomere position effects.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by funds from the Cancer Research Campaign (UK), and Glasgow University.

Abbreviations

- BAC

bacterial artificial chromosome

- FISH

fluorescence in situ hybridization

Footnotes

This work was supported by funds from the Cancer Research Campaign (UK), and Glasgow University.

References

- 1.Holt SE, Shay JW. Role of telomerase in cellular proliferation and cancer. J Cell Physiol. 1999;180:10–18. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199907)180:1<10::AID-JCP2>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wright WE, Piatyszek MA, Rainey WE, Byrd W, Shay JW. Telomerase activity in human germline and embryonic tissues and cells. Dev Genet. 1996;18:173–179. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6408(1996)18:2<173::AID-DVG10>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yashima K, Maitra A, Rogers BB, Timmons CF, Rathi A, Pinar H, Wright WE, Shay JW, Gazdar AF. Expression of the RNA component of telomerase during human development and differentiation. Cell Growth Differ. 1998;9:805–813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim NW, Piatyszek MA, Prowse KR, Harley CB, West MD, Ho PL, Coviello GM, Wright WE, Weinrich SL, Shay JW. Specific association of human telomerase activity with immortal cells and cancer. Science. 1994;266:2011–2015. doi: 10.1126/science.7605428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harle-Bachor C, Boukamp P. Telomerase activity in the regenerative basal layer of the epidermis in human skin and in immortal and carcinoma-derived skin keratinocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:6476–6481. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yasumoto S, Kunimura C, Kikuchi K, Tahara H, Ohji H, Yamamoto H, Ide T, Utakoji T. Telomerase activity in normal human epithelial cells. Oncogene. 1996;13:433–439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramirez RD, Wright WE, Shay JW, Taylor RS. Telomerase activity concentrates in the mitotically active segments of human hair follicles. J Invest Dermatol. 1997;108:113–117. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12285654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shay JW, Bacchetti S. A survey of telomerase activity in human cancer. Eur J Cancer. 1997;33:787–791. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(97)00062-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feng J, Funk WD, Wang SS, Weinrich SL, Avilion AA, Chiu CP, Adams RR, Chang E, Allsopp RC, Yu J, Le S, West MD, Harley CB, Andrews WH, Greider CW, Villeponteau B. The RNA component of human telomerase. Science. 1995;269:1236–1241. doi: 10.1126/science.7544491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meyerson M, Counter CM, Eaton EN, Ellisen LW, Steiner P, Caddle SD, Ziaugra L, Beijersbergen RL, Davidoff MJ, Liu Q, Bacchetti S, Haber DA, Weinberg RA. hEST2, the putative human telomerase catalytic subunit gene, is up-regulated in tumor cells and during immortalization. Cell. 1997;90:785–795. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80538-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakamura TM, Morin GB, Chapman KB, Weinrich SL, Andrews WH, Lingner J, Harley CB, Cech TR. Telomerase catalytic subunit homologs from fission yeast and human. Science. 1997;277:955–959. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weinrich SL, Pruzan R, Ma L, Ouellette M, Tesmer V, Holt SE, Bodnar AG, Lichtsteiner S, Kim NW, Trager JB, Taylor RD, Carlos R, Andrews WH, Wright WE, Shay JW, Harley CB, Morin GB. Reconstitution of human telomerase with the template RNA component and the catalytic protein subunit hTRT. Nat Genet. 1997;17:498–502. doi: 10.1038/ng1297-498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holt SE, Aisner DL, Baur J, Tesmer VM, Dy M, Ouellette M, Trager JB, Morin GB, Toft DO, Shay JW, Wright WE, White MA. Functional requirement of p23 and Hsp90 in telomerase complexes. Genes Dev. 1999;13:817–826. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.7.817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knuutila S, Björkqvist A-M, Autio K, Tarkkanen M, Wolf M, Monni O, Szymanska J, Larramendy ML, Tapper J, Pere H, El-Rifai W, Hemmer S, Wasenius V-M, Vidgren V, Zhu Y. DNA copy number amplifications in human neoplasms. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:1107–1123. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ioannou PA, de Jong PJ. Construction of bacterial artificial chromosome libraries using the modified P1 (PAC) system. In: Dracopoli NC, Haines JL, Korf BR, Moir DT, Morton CC, Seidman CE, Seidman JG, Smith DR, editors. Current Protocols in Human Genetics. New York: Wiley; 1996. pp. 5.15.1–5.15.24. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cong Y-S, Wen J, Bacchetti S. The human telomerase catalytic subunit hTERT: organization of the gene and characterization of the promoter. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:137–142. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.1.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soder AI, Hoare SF, Muire S, Balmain A, Parkinson EK, Keith WN. Mapping of the gene for the mouse telomerase RNA component, Terc, to chromosome 3 by fluorescence in situ hybridization and mouse chromosome painting. Genomics. 1997;41:293–294. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.4621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McLeod HL, Keith WN. Variation in topoisomerase I gene copy number as a mechanism for intrinsic drug sensitivity. Br J Cancer. 1996;74:508–512. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gottschling DE, Aparicio OM, Billington BL, Zakian VA. Position effect at S. cerevisiae telomeres: reversible repression of Pol II transcription. Cell. 1990;63:751–762. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90141-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wright WE, Shay JW. Time, telomeres and tumours: is cellular senescence more than an anticancer mechanism? Trends Cell Biol. 1995;5:293–297. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)89044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heselmeyer K, Macville M, Schröck E, Blegen H, Hellström A-C, Shah K, Auer G, Ried T. Advanced-stage cervical carcinomas are defined by a recurrent pattern of chromosomal aberrations revealing high genetic instability and a consistent gain of chromosome arm 3q. Genes, Chromosomes Cancer. 1997;19:233–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Björkqvist A-M, Husgafvel-Pursiainen K, Anttila S, Karjalainen A, Tammilehto L, Mattson K, Vainio H, Knuutila S. DNA gains in 3q occur frequently in squamous cell carcinoma of the lung but not in adenocarcinoma. Genes, Chromosomes Cancer. 1998;22:79–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bockmuhl U, Schwendel A, Dietel M, Petersen I. Distinct patterns of chromosomal alterations in high- and low-grade head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1996;56:5325–5329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liehr T, Ries J, Wolff E, Fiedler W, Dahse R, Ernst G, Steininger H, Koscielny S, Girod S, Gebhart E. Gain of DNA copy number on chromosomes 3q26-qter and 5p14-pter is a frequent finding in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Int J Mol Med. 1998;2:173–179. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2.2.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolff E, Girod S, Liehr T, Vorderwulbecke U, Ries J, Steininger H, Gebhart E. Oral squamous cell carcinomas are characterized by a rather uniform pattern of genomic imbalances detected by comparative genomic hybridisation. Oral Oncol. 1998;34:186–190. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(97)00079-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pack SD, Karkera JD, Zhuang Z, Pak ED, Balan KV, Hwu P, Park W-S, Pham T, Ault DO, Glaser M, Liotta L, Detera-Wadleigh SD, Wadleigh R. Molecular cytogenetic fingerprinting of eosophageal squamous cell carcinoma by comparative genomic hybridization reveals a consistent pattern of chromosomal alterations. Genes, Chromosomes Cancer. 1999;25:160–168. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2264(199906)25:2<160::aid-gcc12>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Larramendy ML, Tarkkanen M, Blomqvist C, Virolainen M, Wiklund T, Asko-Seljavaara S, Elomaa I, Knuutila S. Comparative genomic hybridization of malignant fibrous histiocytoma reveals a novel prognostic marker. Am J Pathol. 1997;151:1153–1161. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mairal A, Terrier P, Chibon F, Sastre X, Lecesne A, Aurias A. Loss of chromosome 13 is the most frequent genomic imbalance in malignant fibrous histiocytomas. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1999;111:134–138. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(98)00227-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mechtersheimer G, Otaño-Joos M, Ohl S, Benner A, Lehnert T, Willeke F, Möller P, Otto HF, Lichter P, Joos S. Analysis of chromosomal imbalances in sporadic and NF1-associated peripheral nerve sheath tumors by comparative genomic hybridization. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1999;25:362–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soder AI, Hoare SF, Muir S, Going JJ, Parkinson EK, Keith WN. Amplification, increased dosage and in situ expression of the telomerase RNA gene in human cancer. Oncogene. 1997;14:1013–1021. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yi X, Tesmer VM, Savre-Train I, Shay JW, Wright WE. Both transcriptional and posttranscriptional mechanisms regulate human telomerase template RNA levels. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:3989–3997. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.6.3989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Soder AI, Going JJ, Kaye SB, Keith WN. Tumour specific regulation of telomerase RNA gene expression visualized by in situ hybridization. Oncogene. 1998;16:979–983. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Speicher MR, Howe C, Crotty P, du Manoir S, Costa J, Ward DC. Comparative genomic hybridization detects novel deletions and amplifications in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Cancer Res. 1995;55:1010–1013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bockmuhl U, Wolf G, Schmidt S, Schwendel A, Jahnke V, Dietel M, Petersen I. Genomic alterations associated with malignancy in head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 1998;20:145–151. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0347(199803)20:2<145::aid-hed8>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brass N, Ukena I, Remberger K, Mack U, Sybrecht GW, Meese EU. DNA amplification on chromosome 3q26.-q26.3 in squamous cell carcinoma of the lung detected by reverse chromosome painting. Eur J Cancer. 1996;32A:1205–1208. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(96)00016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brass N, Rácz A, Heckel D, Remberger K, Sybrecht GW, Meese EU. Amplification of the genes BCHE and SLC2A2 in 40% of squamous cell carcinoma of the lung. Cancer Res. 1997;57:2290–2294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Petersen I, Bujard M, Petersen S, Wolf G, Goeze A, Schwendel A, Langreck H, Gellert K, Reichel M, Just K, du Manoir S, Cremer T, Dietel M, Ried T. Patterns of chromosomal imbalances in adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma of the lung. Cancer Res. 1997;57:2331–2335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Petersen I, Langreck H, Wolf G, Schwendel A, Psille R, Vogt P, Reichel MB, Ried T, Dietel M. Small-cell lung cancer is characterized by a high incidence of deletions on chromosomes 3p, 4q, 5q, lOq, 13q and 17p. Br J Cancer. 1997;75:79–86. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1997.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ried T, Petersen I, Holtgreve-Grez H, Speicher MR, Schröck E, du Manoir S, Cremer T. Mapping of multiple DNA gains and losses in primary small cell lung carcinomas by comparative genomic hybridization. Cancer Res. 1994;54:1801–1806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sugita M, Tanaka N, Davidson S, Sekiya S, Varella-Garcia M, West J, Drabkin HA, Gemmill RM. Molecular definition of a small amplification domain within 3q26 in tumors of cervix, ovary, and lung. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2000;117:9–18. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(99)00135-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]