Abstract

Halofuginone, an inhibitor of collagen α1(I) gene expression was used for the treatment of subcutaneously implanted C6 glioma tumors. Halofuginone had no effect on the growth of C6 glioma spheroids in vitro, and these spheroids showed no collagen α1(I) expression and no collagen synthesis. However, a significant attenuation of tumor growth was observed in vivo, for spheroids implanted in CD-1 nude mice which were treated by oral or intraperitoneal (4 µg every 48 hours) administration of halofuginone. In these mice, treatment was associated with a dose-dependent reduction in collagen α1(I) expression and dose- and time-dependent inhibition of angiogenesis, as measured by MRI. Moreover, halofuginone treatment was associated with improved re-epithelialization of the chronic wounds that are associated with this experimental model. Oral administration of halofuginone was effective also in intervention in tumor growth, and here, too, the treatment was associated with reduced angiogenic activity and vessel regression. These results demonstrate the important role of collagen type I in tumor angiogenesis and tumor growth and implicate its role in chronic wounds. Inhibition of the expression of collagen type I provides an attractive new target for cancer therapy.

Keywords: halofuginone, C6 glioma, Collagen type I, MRI

Introduction

Angiogenesis, the formation of new vessels, is essential for embryogenesis, wound healing, and regeneration, in addition to its contribution to the maintenance and progression of solid tumors. New vessels are formed by proliferation and migration of endothelial cells in response to the release of diffusible angiogenic factors in concert with the effects of components of the extracellular matrix (ECM). For example, tube formation can be induced in vitro by culturing endothelial cells within 3-D gels of collagen type I [1] or within plasma clots [2]. Capillary endothelial cells cultured on interstitial collagens (type I/III) proliferate to form a continuous cell layer, whereas on basement membrane collagens (type IV/V), they do not proliferate, but rather aggregate to form tube-like structures [3]. During angiogenesis, endothelial cells extensively remodel the ECM around them by secreting enzymes that digest the preexisting basement membrane, and by synthesizing collagen and other molecules which form the ECM of the new capillaries. The microvascular ECM undergoes dynamic changes before achieving its final maturation, starting with the formation of a fibrillary network of fibronectin and type V collagen, followed by the accumulation of a subendothelial matrix of laminin and type IV collagen, and concluding with deposition of types I and III collagen fibrils in the perivascular space [2]. The absence of collagen types I and III during vascular sprouting and their accumulation in later stages of angiogenesis suggest that they may exert a stabilizing effect on the structure of the mature microvessel, by strengthening the extracellular framework of the microvascular wall [2].

It has been suggested that collagen type I, one of the major components of the ECM is involved in angiogenesis. Capillary endothelial cells reorganize into a network of branching and anastomosing capillary-like tubes when sandwiched between two layers of type I collagen gel [1]. Moreover, when collagen type I fibrils make contact with the apical side of the endothelium, they act as a stimulus to provide a template for vascular tube formation [4]. Monoclonal antibodies directed to the α chain of the integrin α2β1, the major integrin receptor for type I collagen on capillary endothelial cells, enhance the number, length, and width of capillary tubes formed by endothelial cells [5]. Anti-α2β1 antibodies have been found to maintain the endothelial cells in rounded morphology and to inhibit both their attachment to and their proliferation on collagen, but not on fibronectin, laminin or gelatin matrices [5]. Thus, restriction of specific cell-matrix interactions can affect capillary formation. Unfortunately, the elucidation of the precise role in angiogenesis of any component of the ECM in general and of collagen type I in particular has been hampered by the lack of inhibitors for specific ECM components.

Previously, we demonstrated that halofuginone, an alkaloid originally isolated from the plant, Dichroa febrifuga, and commonly used as a coccidiostat in chickens and turkeys, suppressed avian skin collagen synthesis in vivo [6]. In animal models with excessive deposition of collagen, such as the murine chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGvHD) and the tight skin (TSK) mouse, halofuginone negated the increase in skin collagen and prevented the thickening of the dermis and the loss of the subdermal fat [7]. In addition, halofuginone has been reported to reduce pulmonary fibrosis in bleomycin-treated rats [8], to prevent dimethylnitrosamine-induced liver cirrhosis [9], to reduce peritendinous fibrous adhesions following surgery [10], to prevent post-operation abdominal [11] and uterine [12] adhesion formation in rats, and to inhibit bladder carcinoma angiogenesis and tumor growth [13]. In all these models, halofuginone inhibited collagen α1(I) gene expression and collagen type I synthesis [14]. In culture, halofuginone has been found to attenuate collagen α1(I) gene expression and collagen production by murine and avian skin fibroblasts [15]; it also reduced collagen α1(I) gene expression and collagen synthesis in human fibroblasts derived from scleroderma and cGvHD patients, and attenuated the transforming growth factor β (TGFβ)-induced increase in collagen α1(I) gene expression by normal human skin fibroblasts [16]. Halofuginone specifically inhibited the gene expression of collagen type α1(I), but not type α2(I), type II [16], type III [17] or type X (M. Pines, unpublished data). Recently, we reported that topical treatment of a cGvHD patient with halofuginone caused an attenuation of collagen α1(I) gene expression demonstrating human clinical efficacy [18].

The goal of the present study was to evaluate the role of collagen type I in angiogenesis and tumor progression. To do so, we used the previously described hypervascularity, aggressive tumor progression, and inhibition of wound repair of C6 glioma spheroids implanted in surgical incisions [19]. This system provides a model for tumor recurrence along surgical incisions, and has led to the hypothesis that under these conditions, inhibition of angiogenesis may inhibit tumor recurrence without attenuating, and possibly improving wound repair [19]. In the present study, we evaluated the ability of halofuginone to affect angiogenesis, tumor growth, and wound healing, when it was applied before C6 glioma spheroid implantation on the wound site or after the establishment of the tumor. Our results demonstrate that halofuginone inhibited the neovascularization and tumor growth in a dose-dependent manner, and facilitated the wound healing. Thus, halofuginone could be used as an important tool in understanding the role of collagen in tumor progression and in wound healing, and it may become a novel and promising antiangiogenic agent in cancer therapy.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Sirius Red F3B was obtained from BDH Laboratory Supplies (Poole, England). A rat collagen α1(I) 1600-bp probe was a generous gift from B. E. Kream, University of Connecticut, CT, USA. Halofuginone bromhydrate was obtained from Roussel UCLAF (Paris, France).

Cell Culture and Spheroid Preparation

C6 rat glioma cells were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 5% fetal calf serum (FCS, Biological Industries, Israel), 50 units ml-1 penicillin, 50 µg ml-1 streptomycin, and 125 µg ml-1 fungizone (Biolab Ltd.). Aggregation of cells into small spheroids of about 150 µm was initiated by replating cells from confluent cultures onto agar-coated bacteriological plates. After 4 to 5 days in culture, the spheroid suspension was transferred to a 250-ml spinner flask (Bellco, USA) and the medium was changed every other day for 30 to 40 days. All culture operations were at 37°C and 5% CO2. Other culture conditions were as reported previously [19,20].

Spheroid Implantation in Nude Mice

Male CD1-nude mice (2-month-old, 30 g body weight) were anesthetized with 75 µg/g Ketamine + 3 µg/g Xylazine (i.p.), and placed in a sterile laminar flow hood. A single spheroid per mouse, about 1 mm in diameter, was implanted subcutaneously in the lower back at the site of a 4-mm incision, using a Teflon tubing, as reported previously [19]. The incision was formed with fine surgical scissors and closed with an adhesive bandage (Tegaderm™, USA).

NMR Microimaging of the Implanted Spheroid

NMR experiments were performed on a horizontal 4.7 T Bruker-Biospec spectrometer using an actively RF decoupled surface coil, 2 cm in diameter, and a bird-cage transmission coil, as reported previously [19,21]. Mice were anesthetized with 75 µg/g Ketamine + 3 µg/g Xylazine (i.p.), and placed supine with the tumor located at the center of the surface coil. Gradient echo (GE) images were acquired with a slice thickness of 0.5 mm, TE of 10 ms, TR of 230 ms and 256x256 pixels matrix resulting in in-plane resolution of 110 µm. Growth of the capillary bed was reflected by reduction of the mean intensity at a region of interest of 1 mm surrounding the spheroid [19–22]. Data are reported here as the apparent vessel density (AVDMRI=-In S(a)/S(0)), where S(a) is the mean intensity at a region of interest of 1 mm surrounding the spheroid and S(0) is the mean intensity of a distant muscle. Tumor volume was determined from two orthogonal sets of multislice gradient echo images covering the entire tumor. MRI data were analyzed on an Indigo-2 work-station (Silicon Graphics, USA) with Paravision software (Bruker, Germany). The statistical significance of the results was determined with Student's t-test or ANOVA. Errors reported are the standard deviations.

Preparation of Sections, In Situ Hybridization and Histochemistry

Multicellular spheroids and samples from tumors adherent to skin were collected into phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS at 4°C. Serial 5-µm sections were prepared after the samples had been dehydrated in graded ethanol solutions, cleared in chloroform, and embedded in Paraplast (Oxford, St. Louis, MO). Differential staining of collagenous and noncollagenous proteins was performed with 0.1% Sirius Red with 0.1% Fast Green as a counterstain, in saturated picric acid. By this procedure, collagen is stained red [23]. For hybridization, the sections were deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated through a graded series of ethanol solutions, rinsed in distilled water (5 minutes), and incubated in 2xSSC (1xSSC contains 0.15 M NaCl and 0.015 M sodium citrate) at 70°C for 30 minutes The sections were then rinsed in distilled water and treated with pronase (0.125 mg/ml in 50 mM Tris-HCl, 5 mM EDTA, pH 7.5) for 10 minutes. After digestion, the slides were rinsed with distilled water, post-fixed in 10% formalin in PBS, blocked in 0.2% glycine, rinsed in distilled water, rapidly dehydrated through graded ethanol solutions, and air dried for several hours. Before hybridization, the 1600-bp rat collagen α1(I) insert was cut out from the original plasmid (pUC18) and inserted into pSafyre. The sections were then hybridized with digoxigenin-labeled collagen α1(I) probe [9,11]. All the preparations for in situ hybridization within each experiment were performed simultaneously with the same probe and with the same specific activity, and all sections were dipped in emulsion and exposed for the same length of time. Digitized maps of the in situ hybridization sections were analyzed using National Institutes of Health (NIH) IMAGE software. A binary presentation was derived and used in determination of the stain density (all tumor areas, five tumors per treatment).

Results

Halofuginone Had No Effect on C6 Glioma Spheroids In Vitro

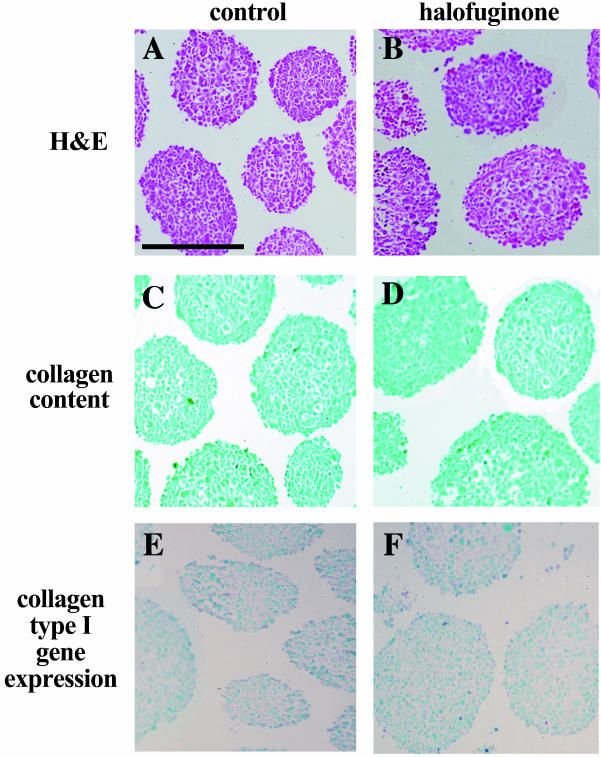

C6 glioma spheroids in culture did not express the gene for collagen α1(I), as demonstrated by in situ hybridization (Figure 1; no red stain in Sirius sections C,D and no expression of collagen α(I) in E,F). In addition, there was no difference in growth rate as manifested by spheroid diameter, between spheroids that were cultured in the presence of halofuginone (10-8 M for 10 days) and the control spheroids. Exposure to halofuginone at 10-8 M has been previously reported to optimally suppress the expression of collagen α(I) in other cells [7].

Figure 1.

In vitro effect of halofuginone on C6 glioma spheroids. (A,C,E) Control spheroids. (B,D,F) Halofuginone-treated spheroids (4 days, 10-8 M). (A,B) Eosin hematoxylin stain. (C,D) Sirius Red stain of collagen. (E,F) In situ hybridization of collagen α1(I) expression. Scale bar, x0.5 mm.

Prevention of Angiogenesis and Tumor Progression by Halofuginone

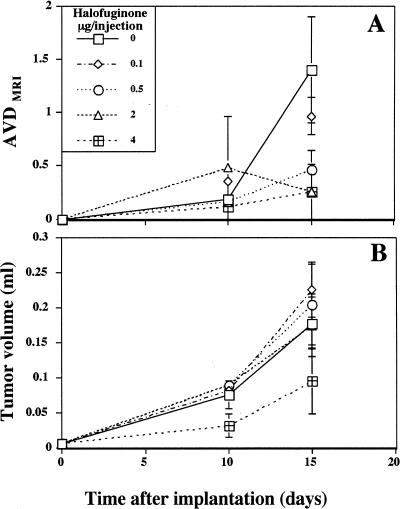

The role of collagen α1(I) in the early stages of tumor progression was evaluated by initiation of halofuginone treatment 1 week before spheroid implantation. Mice were divided into six groups (five mice per group). Five groups received intraperitoneal injections of halofuginone every other day (0, 0.1, 0.5, 2, 4 µg/injection) and one group was fed a diet containing 5 ppm of halofuginone. After 7 days, C6 glioma spheroids (∼750 µm in diameter, one spheroid per mouse) were implanted subcutaneously in the lower backs of the mice at the incision site. MRI studies were performed on days 3, 10, 15, and 20 for a sample of mice from each of the intraperitoneal groups (two mice from each group); and on days 3, 10, and 15 for one of the mice fed with halofuginone. As observed previously for spheroids implanted in a full-thickness dermal incision, the early stages of neovascularization were enhanced in control mice. In contrast, the development of the neovasculature around the tumors in mice treated with halofuginone was inhibited in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 2A). AVDMRI measured 2 weeks after tumor implantation showed that concentrations as low as 0.1 and 0.5 µg/injection inhibited tumor neovascularization by 30% and 60%, respectively. In mice treated with halofuginone at concentrations of 2 and 4 µg/injection, neovascularization was inhibited by 80%. These findings were confirmed at the end of the experiment by examination of skin specimen photographs for all mice (Figure 3, column 2).

Figure 2.

Effect of halofuginone on tumor growth and neovascularization. (A) AVD was measured from GE images at different intervals after tumor implantation (n=2). Note the dose-dependent inhibition of tumor vascularization by halofuginone. (B) Tumor volume was measured from GE images at different intervals after tumor implantation (n=2).

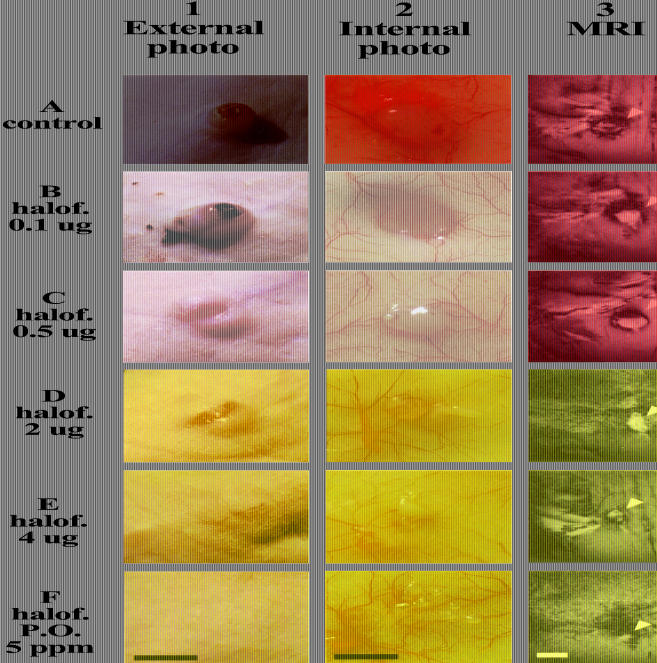

Figure 3.

Halofuginone improves wound healing and inhibits tumor growth in a dose-dependent manner. External (column 1) and internal (column 2) photographs of the skin were taken 20 days after tumor implantation. Coronal GE images were taken 15 days after tumor implantation (column 3; tumors are marked with arrowheads). Collagen α1(I) gene expression (column 4) was evaluated by in situ hybridization (dark brown) and collagen content (column 5) by specific collagen staining (red). Halofuginone treatment reduced expression of collagen α1(I) in the tumor, but did not reduce pre-existing collagen deposited in the skin. Histological eosin hematoxylin staining of the incision shows improved repair with halofuginone treatment (column 6). Scale bar, x5 mm for columns 1 to 3 and x0.5 mm for columns 4 to 6.

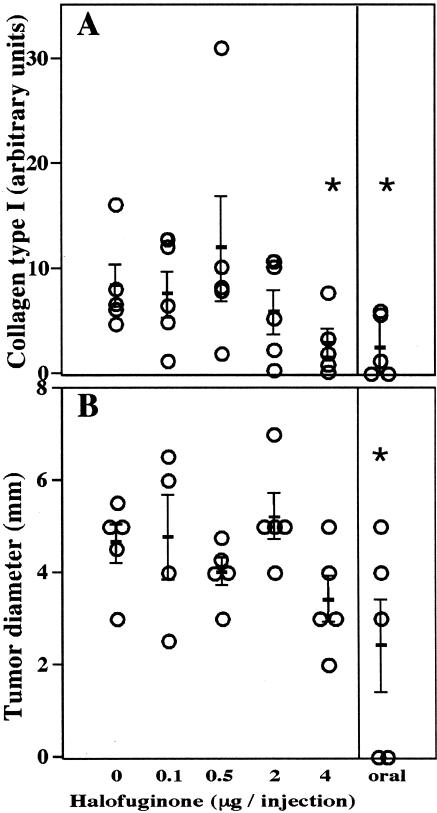

In contrast to the effect of halofuginone on neovascularization, tumor growth was inhibited only by the highest dose of halofuginone (4 µg/injection) or by oral administration of halofuginone. The effect of halofuginone on tumor growth was already apparent 10 days after C6 glioma spheroid implantation and continued until the end of the experiment. Tumor growth in mice treated with lower doses of halofuginone was not significantly different from that in the controls (Figures 2B and 4B). Three weeks after tumor implantation, all the mice were sacrificed and the tumor sizes were measured (Figure 4B). The tumors in mice treated by oral administration of halofuginone were significantly smaller than those in the controls (22.6±12 mm3 and 56±12 mm3, respectively; p=0.04). These mice lost about 30% of their body weight, whereas mice injected with the highest dose of halofuginone (4 µg/injection) did not lose any body weight. In these mice, although the tumors were much smaller than those in the controls, the effect was not statistically significant, because of the large variance (26±11 mm3; p=0.053). There was no correlation between weight loss and tumor growth rate in the orally treated group.

Figure 4.

Effects of halofuginone on tumor growth and collagen synthesis. (A) Quantification of collagen type I gene expression in the tumors (day 20, mean±SD, n=5). (B) Tumor diameter at the end of the experiment (day 20, mean±SE, n=5). The asterisks represent statistically significant difference from the control (t-test, p<0.05).

Previously, we showed that wounds located less than 1 mm from a tumor implantation site did not complete re-epithelialization even 3 weeks after the incision was made, and inflammatory cells and blood clots were observed at the wound site [19]. Halofuginone (oral administration or i.p. administration of 4 µg/injection) significantly improved wound healing, despite the presence of a tumor. Histological sections of the tumors (oral administration and injections of 4 µg/injection) demonstrated complete re-epithelialization in four of five mice in each group. In contrast, in all other groups, only in one of the five mice was re-epithelialization completed. Blood clots were still observed only in control mice and in mice treated with the two lowest doses of halofuginone (0.1 and 0.5 µg/injection; Figure 3, columns 1 and 6).

The level of collagen α1(I) expression was determined by image analysis of the in situ hybridization (Figure 3, column 4), and total collagen content by Sirius Red staining (Figure 3, column 5). There was a dose-dependent effect on collagen α1(I) expression (Figures 3 and 4A), which was significant for oral administration of halofuginone and for the highest dose of halofuginone (4 µg/injection; p=0.025, n=5).

Intervention of Established Tumors by Halofuginone

C6 glioma spheroids (∼1 mm in diameter, one spheroid per mouse) were implanted subcutaneously in the lower backs of the mice, at the incision site. One week after tumor implantation, the mice were randomly divided into two groups (n=6). One group was fed with a normal diet and the other with a diet containing halofuginone (5 ppm) which, as in the previous experiment, caused reduction in body weight. The kinetics of tumor growth and vascularization was followed, twice a week, with GE MRI, for three mice per group. Three weeks after tumor implantation, the mice were photographed and weighed, and the tumors were taken to histology.

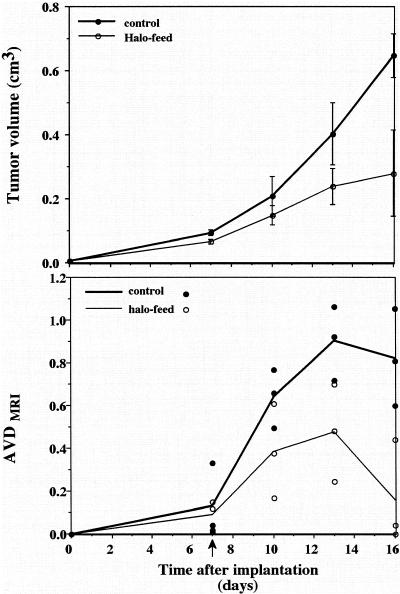

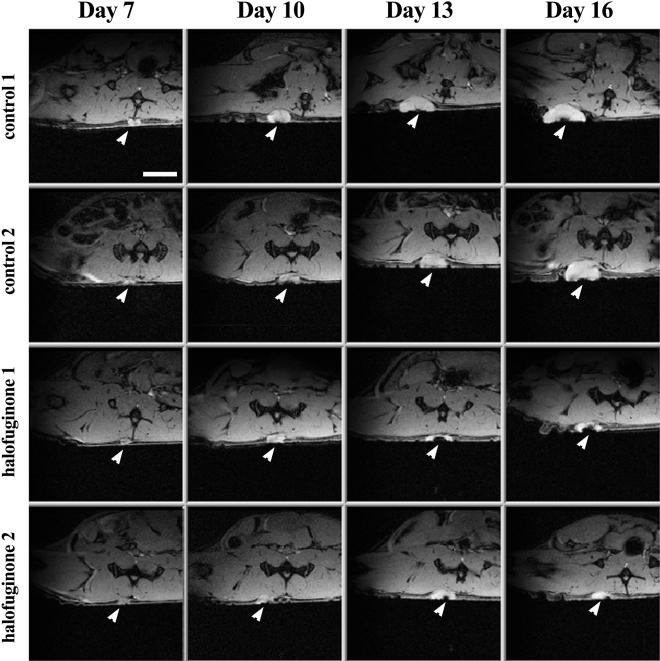

Development of neovasculature around the tumors in mice treated with oral administration of halofuginone stopped 4 days after treatment began, and regression was observed 5 days later (Figure 5B). AVDMRI measured 13 days after tumor implantation showed 47% lower vascularization in treated mice than in the controls (0.48±0.13 compared with 0.9±0.1; p=0.03). Sixteen days after tumor implantation, vascularization in treated mice was about 80% lower than in the controls (0.16±0.14 compared to 0.82±0.13; p=0.013). The reduction in the tumor vascularization was accompanied by a significant arrest in tumor growth in mice treated by oral administration of halofuginone (Figures 5A and 6). Tumor volume in these mice was significantly smaller than in the controls 16 days after tumor implantation (0.28±0.13 cm3 and 0.65±0.07 cm3, respectively; p=0.036) (Figure 5A). As can be seen in the MRI analysis, the tumor in the control animals is growing with time (Figure 6; arrow), whereas the tumors in mice treated with halofuginone on day 7, after the tumor was established, almost stopped growing and were significantly smaller during the entire experiment (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Kinetics of tumor growth and neovascularization. Halofuginone treatment began 7 days after tumor implantation (arrow). Tumor volume (A) and AVD (B) were measured from GE images at different days after tumor implantation. Control (filled circles, n=3) and oral administration of halofuginone (open circles, n=3). Note the arrest in tumor growth and regression of vascularization for mice treated with halofuginone.

Figure 6.

Kinetic analysis of the effect of halofuginone on tumor progression by MRI. Transverse gradient echo images were acquired on a Bruker 4.7 T spectrometer using a whole body excitation coil and an actively decoupled 2 cm surface coil (TE=10 ms, TR=230 ms, field of view of 3.5 cm, slice thickness of 0.5 mm, and total acquisition time of 4 minutes). The arrowheads show the position of the implanted C6 glioma spheroid. Scale bar, x5 mm.

Discussion

The growth and metastatic properties of solid tumors are directly influenced by the process of angiogenesis. Primary tumor growth depends on nutrients supplied by infiltration of blood vessels, while the same vessels also serve as conduits for invasive cells and thereby accelerate the metastatic process. The complex mechanism of angiogenesis provides many steps that can be targeted by pharmacological interventions for the treatment of tumors and wounds. The involvement of ECM components in angiogenesis in vivo has been studied extensively in recent years. Mathematical models predict that ECM-mediated random motility and cell proliferation, which are key processes in driving angiogenesis, and the dependence of these processes on the ECM density and the rate of ECM remodeling determine the angiogenic response [24]. Collagen type I, a major ECM macromolecule has been found to be associated with, and important to, the neovascularization process. For example, drugs that promote early and marked angiogenesis have been found also to cause increased collagen type I deposition [25]. Conversely, delayed neovascularization in aged mice was associated with decrease in collagen type I and TGFβ, the major promoter of collagen type I gene expression [26]. Collagen type I has been found to contain the required heparin-binding domains necessary for endothelial tube formation [27]. Moreover, one of the early events of angiogenesis is the expression of alpha prolyl 4-hydroxylase gene, the major collagen cross-linking enzyme [28]. The dose-dependent inhibition of tumor vascularization by halofuginone (Figure 2A) implies once again that collagen type I is essential for angiogenesis. It seems that collagen type I also participates in persistent tumor-wounds, since mice treated with halofuginone showed improved wound healing even in the presence of a tumor. Thus, although many angiogenic inhibitors have been directed toward blocking the initial cytokine-dependent induction of new vessel growth, the approach based on targeting collagen type I synthesis, to inhibit neovascularization, provides a new and promising therapy avenue.

C6 glioma cells do not synthesize collagen in culture and were not affected by halofuginone (Figure 1). When implanted, cells within the growing tumor expressed the collagen α(1) gene. Expression of collagen α(1) was inhibited by halofuginone (Figure 3), in agreement with our previous observation which demonstrated a specific inhibition of collagen type α1(I) gene expression by halofuginone in various models, with excess of collagen type I synthesis (for review, see Ref. [14]). Consistent with the proposed mode of action, halofuginone affected only collagen α1(I) gene expression and reduced the level of newly synthesized collagen within the tumor, without affecting the resident collagen fibrils in the skin (Figure 3).

The stimulatory effect of wounds on tumors is a recognized clinical phenomenon. We previously demonstrated the enhancing effect of wound healing on tumor angiogenesis and growth, using a system of a multicellular spheroid implanted at different distances from an incision [19,29]. The wound-tumor system presents a major dilemma with respect to anti-angiogenic therapy, since angiogenesis is an essential and integral part of the healing process. If angiogenesis in wound healing and in tumors share a common molecular pathway, inhibition of one might affect the other. However, it is possible that the excessive angiogenic activity associated with the tumor-wounds is beyond that required for healing, and tissue recovery could take place even if angiogenesis was significantly inhibited. Most previously tested anti-angiogenic therapies, including interferon α/β [30], AGM-1470 (a synthetic analogue of fumagillin) [31], and antibodies to b-FGF [32] inhibit wound healing. In the present study, halofuginone, which has been demonstrated to inhibit surgery-induced adhesions in the intestine [11] and uterine horns [12], improved the repair of persistent tumor-associated wounds (Figure 3).

One could expect that inhibition of angiogenesis would provide effective anti-tumor therapy. We found that halofuginone inhibited angiogenesis in a dose-dependent manner, but only the highest doses blocked tumor growth (Figure 2A and B). Thus, inhibition of angiogenesis affected tumor growth only above a certain threshold. The model used here of wound-associated glioma results in highly vascular tumors [19,29]. In such tumors, it is possible that angiogenesis is not limiting tumor growth, and only when suppressed significantly, tumor growth rate becomes sensitive to the vessel density. Improved wound repair was observed even at concentrations in which tumor growth was not significantly inhibited. Thus, the improved healing cannot be explained by the reduced number of tumor cells.

Oral administration of halofuginone was highly effective in prevention of tumor progression (Figures 2 and 3), especially in inhibition of the growth of established tumors (Figures 5A and 6). Moreover, reduction in the existing AVD was observed (Figure 5B). Oral administration of halofuginone was found to be superior to i.p. injection as has been found in other systems [11], this may be due to the longer half-life of halofuginone when administered orally (data not shown). Halofuginone is one of very few antiangiogenic factors that can be orally administered, which makes this therapy clinically attractive. Although reduction in body weight was observed in mice fed a halofuginone-containing diet, the effect of halofuginone on tumor progression could not have been due to nutritional manipulation [33,34], because other routes of administration caused similar effects on the tumors without affecting body weight (Figure 2). Mice, especially nude mice, have been reported to respond with a reduction in food consumption when fed halofuginone-containing diets, in contrast to rats [11], rabbits [17], and chickens [6]. In those species, maximal reduction in the expression of collagen α1(I) gene expression was observed in the adhesion site, in intima hyperplasia of blood vessels and in the skin, respectively, before any change in body weight was observed. The concentration of halofuginone in the diet (5 ppm) was as used previously in other studies [6,11,12].

In conclusion, inhibition of collagen type I synthesis by halofuginone caused inhibition of tumor angiogenesis and tumor progression, while it improved the repair of persistent tumor-associated dermal incisions. These results provide additional evidence for the important role of collagen type I in wound healing and in tumor angiogenesis and progression. Inhibition of collagen synthesis may, therefore, provide a powerful therapeutic approach for the treatment of cancer or other diseases characterized by excessive angiogenesis.

Acknowledgements

R.A. is a recipient of a fellowship from the Charles Clore foundation. M.N. holds a Research Career Development Award from the Israel Cancer Research Fund.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Collgard Biopharmaceutical Ltd.

References

- 1.Montesano R, Orci L, Vassalli P. In-vitro rapid organization of endothelial cells into capillary-like networks is promoted by collagen matrices. J Cell Biol. 1983;97:1648–1652. doi: 10.1083/jcb.97.5.1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nicosia RF, Madri JA. The microvascular extracellular matrix. Developmental changes during angiogenesis in the aortic ring-plasma clot model. Am J Pathol. 1987;128:78–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Madri JA, Williams SK. Capillary endothelial cell cultures: phenotypic modulation by matrix components. J Cell Biol. 1983;91:153–165. doi: 10.1083/jcb.97.1.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jackson CJ, Jenkins KL. Type I collagen fibrils promote rapid vascular tube formation upon contact with the apical side of cultured endothelium. Exp Cell Res. 1991;192:319–323. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(91)90194-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gamble JR, Matthias LJ, Meyer G, Kaur P, Russ G, Faull R, Berndt MC, Vadas MA. Regulation of in-vitro capillary tube formation by anti-integrin antibodies. J Cell Biol. 1993;121:931–943. doi: 10.1083/jcb.121.4.931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Granot I, Bartov I, Plavnik I, Wax E, Hurwitz S, Pines M. Increased skin tearing in broilers and reduced collagen synthesis in skin in vivo and in vitro in response to the coccidiostat halofuginone. Poult Sci. 1991;70:1559–1563. doi: 10.3382/ps.0701559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levi-Schaffer F, Nagler A, Slavin S, Knopov V, Pines M. Inhibition of collagen synthesis and changes in skin morphology in murine graft-versus-host disease and tight skin mice: effect of halofuginone. J Invest Dermatol. 1996;106:84–88. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12328014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nagler A, Firman N, Feferman R, Cotev S, Pines M, Shoshan S. Reduction in pulmonary fibrosis in vivo by halofuginone. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;154:1082–1086. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.154.4.8887611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pines M, Knopov V, Genina O, Lavelin I, Nagler A. Halofuginone, a specific inhibitor of collagen type I synthesis, prevents dimethylnitrosamine-induced liver cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 1997;26:391–398. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(97)80186-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nyska M, Nyska A, Rivlin E, Porat S, Pines M, Shoshan S, Nagler A. Topically applied halofuginone, an inhibitor of collagen type I transcription, reduced peritendinous fibrous adhesions following surgery. Conn Tisue Res. 1996;34:97–103. doi: 10.3109/03008209609021495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nagler A, Rivkind Al, Raphael J, Levi-Schaffer F, Genina O, Lavelin I, Pines M. Halofuginone—an inhibitor of collagen type I synthesis—prevents post-operation abdominal adhesions formation. Ann Surg. 1997;227:575–582. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199804000-00021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nagler A, Genina O, Lavelin I, Ohana M, Pines M. Halofuginone—an inhibitor of collagen type I synthesis—prevents formation of post-operative adhesions formation in the rat uterine horn model. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180:558–563. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70254-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elkin M, Ariel I, Miao HQ, Nagler A, Pines M, de-Groot N, Hochberg A, Vlodavsky I. Inhibition of bladder carcinoma angiogenesis, stromal support and tumor growth by halofuginone. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4111–4118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pines M, Nagler A. Halofuginone—a novel anti-fibrotic therapy. Gen Pharmacol. 1997;30:445–450. doi: 10.1016/s0306-3623(97)00307-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Granot I, Hurwitz S, Halevy O, Pines M. Halofuginone: an inhibitor of collagen type I synthesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993;1156:107–112. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(93)90123-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Halevy O, Nagler A, Levi-Schaffer F, Genina O, Pines M. Inhibition of collagen type I synthesis by skin fibroblasts of graft versus host disease and scleroderma patients: effect of halofuginone. Biochem Pharmacol. 1996;52:1057–1063. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(96)00427-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi ET, Callow AD, Sehgal NL, Brown DM, Ryan US. Halofuginone, a specific collagen type I inhibitor, reduces anastomotic intima hyperplasia. Arch Surg. 1995;130:257–261. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1995.01430030027004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nagler A, Pines M. Topical treatment of cutaneous chronic graft versus host disease (cGvHD) with halofuginone: a novel inhibitor of collagen type I synthesis. Transplantation. 1999 doi: 10.1097/00007890-199912150-00027. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abramovitch R, Marikovsky M, Meir G, Neeman M. Stimulation of tumor angiogenesis by proximal wounds: spatial and temporal analysis by MRI. Br J Cancer. 1998;11:440–447. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abramovitch R, Meir G, Neeman M. Neovascularization induced growth of implanted C6 glioma multicellular spheroids: magnetic resonance microimaging. Cancer Res. 1995;55:1956–1962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abramovitch R, Frenkiel D, Neeman M. Analysis of subcutaneous angiogenesis by gradient echo magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Med. 1998;39:813–824. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910390519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schiffenbauer YS, Abramovitch R, Meir G, Nevo N, Holzinger M, Itin A, Keshet E, Neeman M. Loss of ovarian function promotes angiogenesis in human ovarian carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:13203–13208. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.24.13203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gascon-Barre M, Huet PM, Belgiorno J, Plourde V, Coulombe PA. Estimation of collagen content of liver specimens. Variation among animals and among hepatic lobes in cirrhotic rats. J Histochem Cytochem. 1989;37:377–381. doi: 10.1177/37.3.2465335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Olsen L, Sherratt JA, Maini PK, Arnold F. A mathematical model for the capillary endothelial cell-extracellular matrix interactions in wound-healing angiogenesis. IMA J Math Appl Med Biol. 1997;14:261–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DaCosta ML, Regan MC, al Sader M, Leader M, Bouchier-Hayes D. Diphenylhydantoin sodium promotes early and marked angio-genesis and results in increased collagen deposition and tensile strength in healing wounds. Surgery. 1998;123:287–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reed MJ, Corsa A, Pendergrass W, Penn P, Sage EH, Abrass IB. Neovascularization in aged mice: delayed angiogenesis is coincident with decreased levels of transforming growth factor beta1 and type I collagen. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:113–123. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sweeney SM, Guy CA, Fields GB, Antonio JDS. Defining the domains of type I collagen involved in heparin- binding and endothelial tube formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:7275–7280. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cockerill GW, Varcoe L, Meyer GT, Vadas MA, Gamble JR. Early events in angiogenesis: cloning an alpha-prolyl 4-hydroxylase-like gene. Int J Oncol. 1998;13:595–600. doi: 10.3892/ijo.13.3.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abramovitch R, Marikovsky M, Meir G, Neeman M. Stimulation of tumor growth by wound derived growth factors. Br J Cancer. 1999;79:1392–1398. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stout AJ, Gresser I, Thompson WD. Inhibition of wound healing in mice by local interferon alpha/beta injection. Int J Exp Pathol. 1993;74:79–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Folkman J. Antiangiogenic gene therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:9064–9066. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Broadley KN, Aquino AM, Woodward SC, Buckley-Sturrock A, Sato Y, Rifkin DB, Davidson JM. Monospecific antibodies implicate basic fibroblast growth factor in normal wound repair. Lab Invest. 1989;61:571–575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Daly JM, Reynolds HM, Rowlands BJ, Dudrick SJ, Copeland EM. Tumor growth in experimental animals: nutritional manipulation and chemotherapeutic response in the rat. Ann Surg. 1980;191:316–322. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198003000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klurfeld DM, Weber MM, Kritchevsky D. Inhibition of chemically induced mammary and colon tumor promotion by caloric restriction in rats fed increased dietary fat. Cancer Res. 1987;47:2759–2762. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]