Abstract

The effects of hyperoxia (induced by host carbogen [95% oxygen/5% carbon dioxide breathing] and hypoxia (induced by host carbon monoxide [CO at 660 ppm] breathing) were compared by using noninvasive magnetic resonance (MR) methods to gain simultaneous information on blood flow/oxygenation and the bioenergetic status of rat Morris H9618a hepatomas. Both carbogen and CO breathing induced a 1.5- to 2-fold increase in signal intensity in blood oxygenation level dependent (BOLD) MR images. This was due to a decrease in deoxyhemoglobin (deoxyHb), which acts as an endogenous contrast agent, caused either by formation of oxyhemoglobin in the case of carbogen breathing, or carboxyhemoglobin with CO breathing. The results were confirmed by observation of similar changes in deoxyHb in arterial blood samples examined ex vivo after carbogen or CO breathing. There was no change in nucleoside triphosphates (NTP)/Pi in either tumor or liver after CO breathing, whereas NTP/Pi increased twofold in the hepatoma (but not in the liver) after carbogen breathing. No changes in tumor intracellular pH were seen after either treatment, whereas extracellular pH became more alkaline after CO breathing and more acid after carbogen breathing, respectively. This tumor type and the liver are unaffected by CO breathing at 660 ppm, which implies an adequate oxygen supply.

Keywords: Morris hepatoma, carbogen, carbon monoxide, BOLD MRI 31P MRS

Introduction

Tumor hypoxia is a considerable barrier to successful radiotherapy as hypoxic cells are radioresistant, and ways of identifying tumor hypoxia have been sought for many years. Breathing hyperoxic gases has been proposed as a means to reduce tumor hypoxia by increasing the amount of dissolved oxygen in the plasma. However, because breathing oxygen also induces vasoconstriction, mixtures of oxygen and carbon dioxide (e.g., carbogen—95% O2/5% CO2) are more effective. The CO2 component of carbogen is thought to maintain tumor blood flow by reducing hyperoxic vasoconstriction and improve oxygen delivery by shifting the hemoglobin-oxygen dissociation curve to the right (1). In contrast, carbon monoxide (CO) is known to cause hypoxia because the affinity of deoxyHb for CO is much greater than it is for O2.

Noninvasive magnetic resonance (MR) methods to identify the hypoxia/oxygenation status of individual tumors are being developed and may ultimately indicate the way in which an individual tumor may respond to treatment in the clinic. Recently, we have used a noninvasive 1H MR technique, gradient-recalled echo (GRE) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), with high temporal and spatial resolution, to monitor the response of various tumor types to carbogen breathing (2, 3). Contrast in GRE MR images is related to the spin-spin MR relaxation time in the presence of magnetic field inhomogeneities, described by the parameter T2*. Deoxyhemoglobin (deoxyHb), which is paramagnetic, creates large field inhomogeneities around blood vessels, shortening T2*, and thus acts as an endogenous, blood oxygenation level dependent (BOLD) contrast agent (4). The hyperoxia of carbogen breathing significantly increases T2* by decreasing deoxyHb, which results in increased signal intensity in T2*-weighted images of tumors; thus it can be used to monitor changes in deoxyHb. These observations have been made in several rodent (2, 3 ,5 ,6) and human tumors (7) and are proposed to be a consequence of an improvement in both tumor oxygenation and blood flow (8–10).

There are numerous studies demonstrating that improving tumor oxygenation through host carbogen breathing improves radiation response (1, 11, 12), and similarly, studies showing a reduction in the radioresponse of human tumors after host CO breathing, consistent with the long-held hypothesis that hypoxia confers radioresistance (13, 14). In preclinical studies, a decrease in tumor oxygenation (measured by Eppendorf pO2 histography) and radioresponse with CO breathing was found in murine C3H mammary carcinomas and SCCVII squamous cell carcinomas (15–17). However, despite an increase in hypoxia, CO breathing induced no change in the NTP/Pi ratio of C3H mammary adenocarcinomas (18). The NTP/Pi ratio is a parameter reflecting the bioenergetic status of tissues and has been shown in some tumors to correlate with oxygenation status (19, 20).

The principal aim of this study was to evaluate the effects of hyperoxia (induced by host carbogen breathing) and hypoxia (induced by host CO breathing) on both blood flow/oxygenation and the bioenergetic status (NTP/Pi) on transplanted rat Morris 9618a hepatomas (H9618a) by using interleaved noninvasive MR techniques. In addition, 31P MR spectroscopy (MRS) gives information on intra- and extracellular pH (pHi and pHe). The response of the tissue of origin, the liver, to carbogen and CO was also monitored by 31P MRS, because assessing the bioenergetic status of normal tissue might be useful when optimizing radiotherapy for hepatic cancers and trying to protect normal tissue from radiation damage. Areas of low O2 concentration have been identified in the liver (21) and the radiosensitivity of normal hepatocytes studied (22). We looked to see if some useful information was reflected in measurements of the bioenergetic status of the liver during hyperoxia or hypoxia. In addition, estimates of T2* of whole rat arterial blood were determined ex vivo after the host breathed air, carbogen, or CO. These estimates were made to confirm and clarify some of the results.

Materials and Methods

The well-characterized transplantable H9618a hepatoma was implanted subcutaneously into the flanks of Buffalo rats (23). Tumor cells, from a serial passage of a cell homogenate, were injected subcutaneously into 200 to 250 g rats and tumors grown to 1.5 to 2 cm diameter. Anesthesia was induced with an intraperitoneal injection of a combination of fentanyl citrate (0.315 mg/mL) plus fluanisone (10 mg/mL) (Hypnorm, Janssen Pharmaceutical Ltd); midazolam (5 mg/mL) (Hypnovel, Roche); and water (1:1:2), at a dose of 4 mL/kg. This anesthetic mixture has been shown to have a minimal effect on tumor blood flow (24) and 31P MRS characteristics (25).

For the tumors (n=5 per treatment group), interleaved 1H MRI/31P MRS was performed with a 4.7 T SISCO (Spectroscopy Imaging Systems Corporation) instrument fitted with a 10 G/cm, 12-cm bore high-performance auxiliary gradient insert. The extracellular pH marker, 3-aminopropyl phosphonate (3-APP) (Sigma, UK) was administered at 1.54 g/kg i.p. 30 minutes before data acquisition (26). Rats were placed on a flask containing recirculating warm water to maintain the core temperature at 35°C and positioned so the tumor hung freely within a 3-cm two-turn double-tuned coil. For normal tissue, a small midline incision of the abdominal wall was made, and 31P MRS alone was performed with a 2-cm two-turn coil placed directly on the liver (n=4 per treatment group). Before data acquisition, field homogeneity was optimized by shimming on the water signal for each tumor to a linewidth typically of 50 to 70 Hz. Carbogen (2 L/min) was administered via a nosepiece equipped with a scavenger, and CO (660 ppm in air) was administered (2–4 L/min) via a nosepiece.

Images were acquired from a single 1-mm slice taken through the center of the tumor using a gradient-recalled echo (GRE) imaging sequence, with an echo time (TE) of 20 ms, repetition time (TR) of 80 ms, and flip angle (α) of 45°. Each image took 4 minutes to acquire using 256 phase encode steps over a 4-cm field-of-view (FOV) with 8 averages. Nonlocalized 31P spectra were acquired using a hard pulse with TR=3 s and 64 acquisitions. Imaging and spectroscopy each took 4 minutes. MRI and MRS were performed alternately for 14 minutes while the animal breathed air and for an additional 60 minutes while the animal breathed either CO or carbogen. In separate experiments, nonlocalized 31P MR spectra were acquired from the liver (TR=2 s, 64 acquisitions) for 14 minutes before and 60 minutes after carbogen or CO inhalation.

For the images, a region of interest (ROI) encompassing the whole tumor 1H image but excluding the skin was chosen and the average pixel intensity calculated. The average pixel intensity in the ROI during initial air breathing was set to 100%. Spectral analysis was performed by the VARPRO time-domain nonlinear least squares method (27, 28). For each VARPRO analysis the first four data points were excluded from the fit to eliminate the influence of fast-decaying signals from immobilized phosphates which cause a baseline hump in the spectra. The data were fitted from the contributions of 3-aminopropylphosphonate (3-APP), phosphomonesters (PME), Pi, phosphocreatinine (PCr) (when present), and the three NTP resonances, and peaks were assumed to be single Lorentzians. Relative peak area ratios of βNTP/Pi were then determined. Tumor pHi and pHe were determined from the VARPRO-derived frequencies for the Pi, 3-APP, and α-NTP resonances (29).

Arterial blood was taken from the aorta of rats that had breathed air, carbogen, or CO for at least 10 minutes; it was then put into evacuated tubes such that the tubes were completely full. The tubes were inserted into a saline bath, placed perpendicular to the main magnetic field, and the slice plane chosen to be perpendicular to the tube axis. In order to obtain estimates for the T2* relaxation time, signal intensity (SI) measurements with a gradient echo sequence were made with increasing TE to produce images with increasing T2*-weighting. Estimates of T2* were obtained by plotting In(SI) versus TE, the gradient of which is equal to 1/T2*. A decrease in the slope reflects a decrease in deoxyHb. Measurements were made in triplicate.

Results are presented as the mean±standard error, and significance testing used the 2-tailed Student t-test.

Results

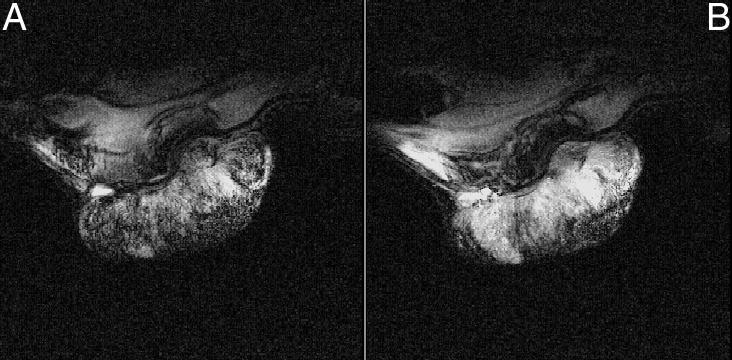

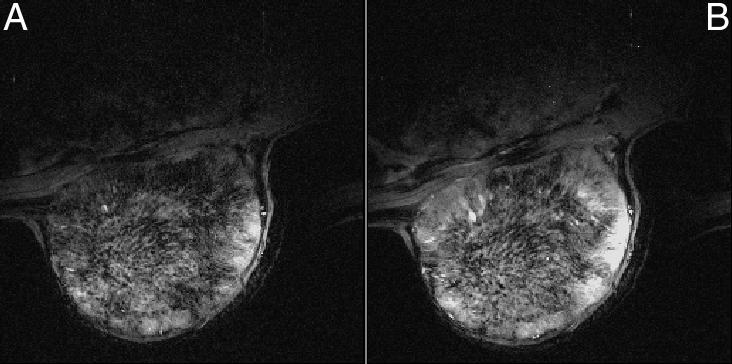

Figure 1 shows GRE images obtained from a H9618a hepatoma 1) during initial air breathing and 2) after 40 minutes CO breathing. Figure 2 shows another hepatoma 1) after initial air breathing and 2) after 40 minutes carbogen breathing. All GRE images were typically heterogeneous, with regions of high intensity in the baseline images becoming more intense during either carbogen or CO breathing, while regions with little or no signal remained unaffected. Both gas breathing regimens caused an increase in image intensity.

Figure 1.

GRE MR images obtained from a H9618a hepatoma during (A) initial air breathing and after (B) 40 minutes breathing CO (660 ppm in air).

Figure 2.

GRE MR images obtained from a H9618a hepatoma during (A) initial air breathing and after (B) 40 minutes breathing carbogen.

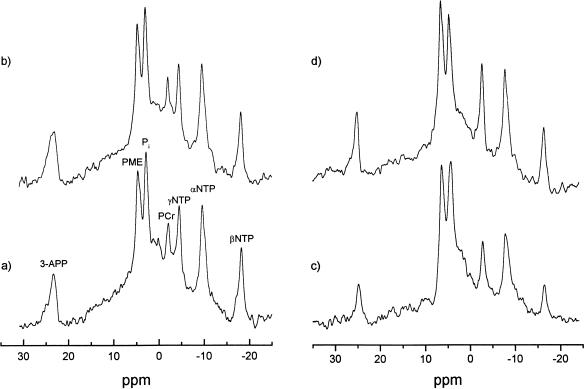

Figure 3 shows 31P spectra obtained from the tumors in Figures 1 and 2 before and during either CO (Figure 3A, B) or carbogen (Figure 3C, D) breathing. Resonances were identified for 3-APP, PME, Pi, PCr, and γ-, α- and β-NTP. Since hepatomas contain negligible PCr, contributions from this resonance can be used as a sensitive indicator of muscle signal contribution (muscle having much higher levels than the tumor). The PCr peak, where detected, was small and always less than that of NTP in the spectra obtained. An increase in the NTP and a decrease in the Pi are discernible in Figure 3D compared with Figure 3C after carbogen breathing, whereas no obvious changes in NTP or Pi were seen after CO breathing. Occasionally we observed slight differences in the amount of extracellular marker (3-APP) present (Figure 3C and D) as the 3-APP, which is administered i.p, changes with time while the MR acquisitions are made. The 3-APP appeared in the tumor about 10 minutes after i.p injection and started to disappear after about 1 hour. However, it is the frequency of the peak, rather than the intensity, that is important, because the pHe measurement is dependent on the difference in chemical shift between the α-NTP and 3-APP signals.

Figure 3.

Nonlocalized 31P spectra acquired from (a) the same H9618a hepatoma shown in Figure 1 and (b) after 40 minutes CO breathing, (c) A second H9618a hepatoma shown in Figure 2 during initial air breathing and (d) after 40 minutes carbogen breathing. Resonances were identified for 3-APP, 3-aminopropylphosphonate; PME, phosphomonesters; Pi, inorganic phosphate; PCr, phosphocreatine; NTP, nucleoside triphosphate.

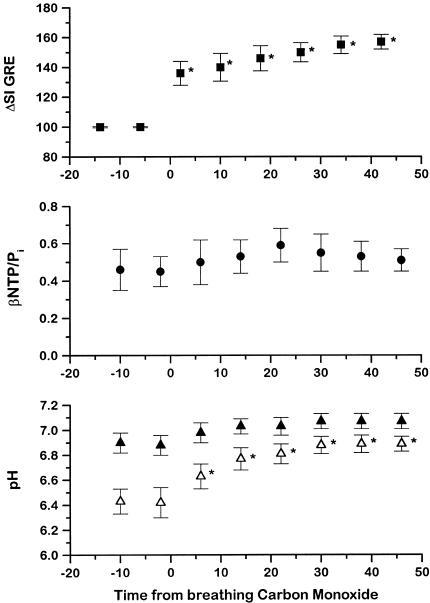

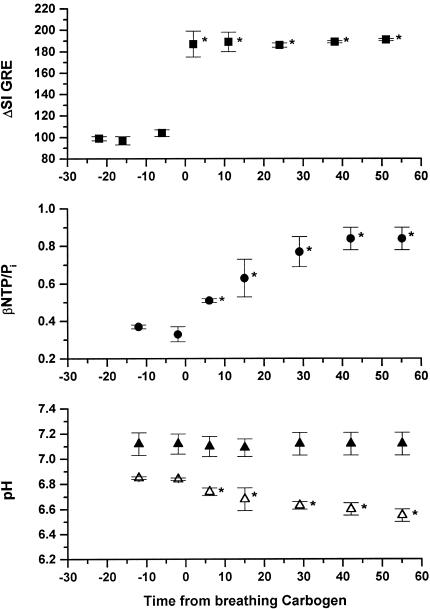

The variation of normalized GRE MR image intensity, βNTP/Pi, and pH with time before and during CO breathing is shown in Figure 4. The GRE MR image intensity over the whole tumor significantly increased by 57±5% after 40 minutes CO breathing. There was no significant change in βNTP/Pi (0.52±0.02) or pHi (7.00±0.03), whereas there was a significant increase in pHe from 6.43±0.1 to 6.89±0.13 (P<.05) over the period studied. During carbogen breathing (Figure 5), the GRE MR image intensity increased by 84±7%, but in contrast to the CO breathing results, the βNTP/Pi ratio increased twofold (from 0.52±0.13 to 1.06±0.21) over the period studied. As with CO breathing, pHi remained around neutrality (7.10±0.05), whereas pHe decreased significantly from 6.79±0.03 to 6.47±0.1 (P<.05) (see also Ref. 30).

Figure 4.

Variation in normalized GRE MRI intensity (■), βNTP/Pi (●), pHi (▲), and pHe (△) obtained from interleaved experiments on H9618a hepatomas during initial air and subsequent CO breathing (mean±SEM, n=5). *P<.05, Student 2-tailed t-test. Tissue pHi and pHe, were determined by using the VARPRO-derived frequencies for the Pi, 3-APP, and α-NTP resonances.

Figure 5.

Variation in normalized GRE MRI intensity (■), βNTP/Pi (●), pHi (▲), and pHe (△) obtained from interleaved experiments on H9618a hepatomas, during initial air and subsequent carbogen breathing (mean±SEM, n=5). *P<.05, Student 2-tailed t-test. Tissue pHi and pHe, were determined by using the VARPRO-derived frequencies for the Pi, 3-APP, and α-NTP resonances.

When the liver was studied with 31P MRS, the baseline (host breathing air) βNTP/Pi ratio of the liver was 3.40±0.12, pHi was 7.39±0.1, and pHe was 6.94±0.1 (n=8). No significant changes in these parameters were observed in the liver in response to either host CO or carbogen breathing (results not shown P>.1). The mean pHe value, determined from the 3-APP signal, is similar to that previously reported for normal subcutaneous tissue (26) but rather lower than the well-established values of normal tissue pHe of 7.3 to 7.4 (19, 31, 32). This could be due to either 1) bias due to presence of excess 3-APP (which is slightly acidic) in the peritoneal cavity (the route of administration was i.p. and the coil was placed directly on the exposed liver) or 2) to sequestration in the Kupffer cells/acidic vesicles present in liver tissue. To test if 3-APP was reporting a pHe value that was unrepresentative of normal tissue, similar experiments were performed in skeletal muscle where Kuppfer cells are not present. In these experiments pHe was shown to be 7.39 in comparison with a pHi of 7.4 (N. Raghunarand, personal communication), suggesting that 3-APP is reporting an erroneously low pHe of the liver in vivo. Further experiments to look at the distribution of MR-visible extracellular markers in different normal tissues are currently being performed, and preliminary results with the fluorinated extracellular pH marker ZK 150471 (32) gave a value of 7.36 for liver (A.S.E. Ojugo, personal communication).

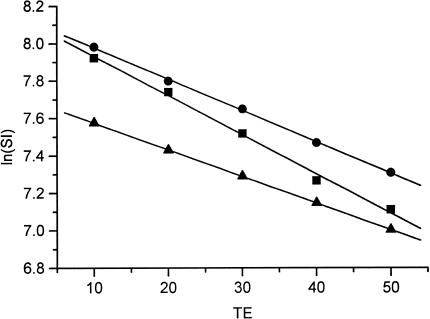

Since the finding that CO (a hypoxic gas) breathing caused a similar GRE MR signal intensity increase to that found with carbogen breathing (a hyperoxic gas), an experiment to assess the effects of carbogen and CO on arterial blood T2* in vitro was also performed (4). A decrease in the slope of In(SI) against TE is consistent with a decrease in deoxyHb (Figure 6). Arterial blood obtained from rats breathing either CO or carbogen showed a decrease in this slope compared to air-breathing controls, resulting in a significant increase in T2* from 46 to 71 ms (P<.00001) with CO and 53 ms (P<.05) with carbogen. This is in accordance with the theory (33) and the results obtained in vivo. Since rat blood hemoglobin is 94% saturated with oxygen when air is breathed, carbogen breathing might be expected to take this up to ∼99% (i.e., there would be a decrease from 6% to 1% in deoxyHb). CO (at 660 ppm) breathing causes about half of the Hb to be bound and unavailable, and of the remaining half about 94% would still be saturated with oxygen (in this case the balance of the gas is air), suggesting a decrease from 6% to 3% in deoxyHb. These projected decreases are consistent with the results.

Figure 6.

Representative plots of In(signal intensity) against echo time (TE) for a sample of arterial blood obtained from rats breathing air (■), carbogen (●), or CO (▲). Measurements were made in triplicate. A decrease in the slope is consistent with a decrease in deoxyhemoglobin and an increase in T2*. Estimates of R2* (1/T2*) were determined from the slopes, corresponding to 46 ms for control blood, 53 ms for carbogen-treated blood, and 71 ms for CO-treated blood.

Discussion

We have previously shown that carbogen breathing induces large increases in the GRE image intensity of H9618a hepatomas (3). For adequate temporal resolution, data were acquired with TE=20 ms, resulting in GRE MR images sensitive to changes in both tumor blood oxygenation and blood flow. Acquisition of images over a range of echo times (as performed in the experiment with the whole blood), would generate tumor T2* maps and would afford easier interpretation of the tumor image intensity changes. However, in the present experiments, performed at only one echo time, it is unclear whether the nonresponding tumor regions seen in Figures 1 and 2 result from areas of necrosis or from regions with very low blood flow. In another transplanted rat tumor type, where multiecho experiments were performed, we have shown that the GRE image intensity increase with carbogen breathing is predominantly due to an increase in T2*, that is, an increase in blood oxygenation (34).

In the present study, breathing CO also induced an increase in GRE image intensity, despite intensifying tumor hypoxia, whereas carbogen causes an improvement in oxygen content. Although this finding was initially counter-intuitive (it was assumed that an increase in hypoxia would cause a decrease in signal intensity as previously observed with modifiers that decrease blood flow/oxygenation (8)), it has a logical explanation. In both cases the increase in GRE image intensity is due to a fall in deoxyHb. Carbogen breathing increases blood oxygenation and thereby the oxyHb/deoxyHb ratio, also improving tumor oxygenation (30). CO decreases deoxyHb by forming carboxyhemoglobin (CO-Hb), thus also decreasing oxyHb and presumably tumor oxygenation. The observed increase in T2* of CO-treated arterial rat blood confirms this interpretation. The presence of paramagnetic deoxyHb, acting as an endogenous contrast agent, shortens T2* which would result in the loss of GRE contrast in tumor images. Low concentrations of CO can lead to significant levels of CO-Hb in the blood, as the affinity of deoxyHb for CO is approximately 230 times that for O2. Breathing 660 ppm CO sequesters 45% of total hemoglobin as CO-Hb (16), the equivalent of decreasing the oxygen content of air from 21% to about 10%. CO-Hb is itself not paramagnetic (35), but an increase in CO-Hb causes a decrease in deoxyHb (which is paramagnetic), with a concomitant increase in GRE image contrast (4).

Nordsmark and colleagues (36) have shown in C3H mouse mammary carcinomas that breathing different hyper- and hypoxic gases (O2, carbogen, air, and CO at 75, 220, and 660 ppm) correlates well with 1) the amount of radiobiological hypoxia measured from radiation response data and 2) the oxygenation status measured by Eppendorf electrodes. Although breathing 660 ppm CO compromised the radiation response in the CH3 mammary carcinoma, the βNTP/Pi ratio did not change (18), which is similar to the findings described here for H9618a. In spite of significant changes shown in the GRE MRI in response to the challenge of 50 minutes CO breathing, both the tumor and liver βNTP/Pi ratio remained unchanged. This suggests that the remaining 55% total hemoglobin (45% as CO-Hb) is sufficient to transport enough oxygen for maintenance of tumor and liver energy status. This is probably more surprising for the liver than the tumor, because many tumors use less than 50% of the oxygen supplied to them (24%–46% depending on tumor type), whereas 18% to 38% of the glucose available was consumed (37). Circulating glucose would still be available even in the presence of CO, although there is some evidence that CO decreases blood flow (15–17).

According to Samsel and colleagues (38), the critical O2 delivery in a canine liver study was 28±5 mL/kg/min, and the livers extracted 68±9% of the delivered O2 before reaching supply dependence. Liver does not use glucose above this critically dependent O2 delivery point but synthesizes it from circulating lactate. However, below this critical level, glucose may be used. In hypoxia experiments on rats (39), it has been shown that there is little change in the NTP levels when the rats were given 10% rather than 20% oxygen to breathe for 20 hours. This was put down to hypoxia depressing energy expenditure to maintain normoxic levels of NTP. Since no decrease in βNTP/Pi was observed in the livers in our experiments after 40 minutes of CO breathing, this suggests that either the O2 available was still above the critical level, or that energy expenditure had been depressed. Indeed hyperoxia did not increase βNTP/Pi in the liver, so in spite of reports of livers containing areas of low O2 concentration (21), it appears that the levels of high energy phosphates are well controlled in liver tissue because no changes were observed when it was being perfused by either hypo- or hyperoxic blood.

Host carbogen breathing has been shown to increase both the βNTP/Pi ratio and tumor pO2, measured polarographically, in H9618a hepatoma (30) and C3H mammary adenocarcinoma (18), suggesting that, at least in these tumor types, the ability to switch to a more oxidative metabolism is maintained. However, circulating blood glucose levels are increased in carbogen breathing (30), and we suggest that it is the availability of glucose that might be rate limiting in tumor metabolism. Neutral pHi was maintained under both hypoxic and hyperoxic conditions, but because of the acid load of the CO2 in carbogen, the pHe decreased significantly after carbogen breathing, following the trend of the blood pH which also decreased (30). With CO breathing tumor pHe increased, and preliminary data have shown that plasma pH also increases in response to CO (F.U. Nielsen, personal communication). The expected long-term pathology of CO poisoning would suggest an overall acidosis due to decreased oxidative and increased glycolytic metabolism. However, with exposure to CO at 660 ppm, the slight alkalinization of the tumor extracellular fluid, as reported by 3-APP, seems to reflect the trend towards alkalinization observed in the blood and may be a consequence of other complex interactions at the interstitial/vasculature interface caused by the accumulation of CO-Hb.

In summary, we have shown that the H9618a hepatoma responds to hyperoxia caused by carbogen breathing in terms of both GRE MR imaging and phosphorylation status, whereas no change in tumor bioenergetic status was seen with hypoxia caused by CO breathing. However, there was an increase in GRE MR image intensity with CO breathing. The GRE MRI method may represent a more sensitive method than 31P MRS for assessing the effects of agents designed to increase tumor hypoxia for therapeutic gain, e.g., for bioreductive therapy (40). In addition, there were no changes in the βNTP/Pi of liver with either hyperoxia or hypoxia, suggesting that regulation of the phosphorylation state of the liver is well controlled. The MR information described herein can be obtained noninvasively on standard clinical MR instruments and could be useful in patient treatment decision making.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Cancer Research Campaign, UK, [CRC] grant SP 1971/0402. The authors would like to thank Dr. Lindsay Bashford for helpful discussions, Drs. Natarajan Raghunarand, Flemming Nielsen and Agatha Ojugo for sharing their data, and Chris Brown and his staff for care of the animals.

Abbreviations

- BOLD

blood oxygenation level dependent

- CO-Hb

carboxyhemoglobin

- deoxyHb

deoxyhemoglobin

- GRE MRI

gradient recalled echo MRI

- H9618a

Morris hepatoma 9618a

- MR

magnetic resonance

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- MRS

magnetic resonance spectroscopy

- NTP

nucleoside triphosphates

- oxyHb

oxyhemoglobin

- pHe

extracellular pH

- pHi

intracellular pH

References

- 1.Rojas A. Radiosensitisation with normobaric oxygen and carbogen. Radiother Oncol. 1991;20(suppl 1):65–70. doi: 10.1016/0167-8140(91)90190-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robinson SP, Howe FA, Griffiths JR. Noninvasive monitoring of carbogen-induced changes in tumor blood flow and oxygenation by functional magnetic resonance imaging. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;33:855–859. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(95)00072-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robinson SP, Rodrigues LM, Ojugo ASE, McSheehy PMJ, Howe FA, Griffiths JR. The response to carbogen breathing in experimental tumour models monitored by gradient-recalled echo magnetic resonance imaging. Br J Cancer. 1997;75:1000–1006. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1997.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ogawa S, Lee TM, Nayak AS, Glynn P. Oxygenation-sensitive contrast in magnetic resonance image of rodent brain at high magnetic fields. Magn Reson Med. 1990;14:68–78. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910140108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dunn JF, Swartz HM. Blood oxygenation: Heterogeneity of hypoxic tissues monitored using BOLD MR imaging. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1997;428:645–650. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oikawa H, Al-Hallaq HA, Lewis MZ, River JN, Kovar DA, Karczmar GS. Spectroscopic imaging of the water resonance with short repetition time to study tumor response to hyperoxia. Magn Reson Med. 1997;38:27–32. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910380106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Griffiths JR, Taylor NJ, Howe FA, Saunders MI, Robinson SP, Hoskin PJ, Powell MEB, Thoumine M, Caine LA, Baddeley H. The response of human tumors to carbogen breathing, monitored by gradient-recalled echo magnetic resonance imaging. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;39:697–701. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(97)00326-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Howe FA, Robinson SP, Griffiths JR. Modification of tumour perfusion and oxygenation monitored by gradient recalled echo MRI and 31P MRS. NMR Biomed. 1996;9:208–216. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1492(199608)9:5<208::AID-NBM418>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al-Hallaq HA, River JN, Zamora M, Oikawa H, Karczmar GS. Correlation of magnetic resonance and oxygen microelectrode measurements of carbogen-induced changes in tumor oxygenation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1998;41:151–159. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(98)00038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robinson SP, Collingridge DR, Howe FA, Rodrigues LM, Chaplin DJ, Griffiths JR. Tumour response to hypercapnia and hyperoxia monitored by FLOOD magnetic resonance imaging. NMR Biomed. 1999;12:98–106. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1492(199904)12:2<98::aid-nbm556>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoskin PJ, Saunders MI, Phillips H, Cladd H, Powell MEB, Goodchild K, Stratford MRL, Rojas A. Carbogen and nicotinamide in the treatment of bladder cancer with radical radiotherapy. Br J Cancer. 1997;76:260–263. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1997.372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaanders JHAM, Pop LAM, Marres HAM, Liefers J, van den Hoogen FJA, van Daal WAJ, van der Kogel AJ. Accelerated radiotherapy with carbogen and nicotinamide (ARCON) for laryngeal cancer. Radiother Oncol. 1998;48:115–122. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(98)00043-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kucera H, Enzelsberger H, Eppel W, Weghaupt K. The influence of nicotine abuse and diabetes mellitus on the results of primary irradiation in the treatment of carcinoma of the cervix. Cancer. 1987;60:1–4. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19870701)60:1<1::aid-cncr2820600102>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Browman GP, Wong G, Hodson I, Sathya J, Russell R, McAlpine L, Skingley P, Levine MN. Influence of cigarette smoking on the efficacy of radiation therapy in head and neck cancer. New Engl J Med. 1993;328:159–163. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199301213280302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grau C, Horsman MR, Overgaard J. Influence of carboxyhemoglobin level on tumour growth, blood flow and radiation response in an experimental model. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1992;22:421–424. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(92)90845-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grau C, Khalil AA, Nordsmark M, Horsman MR, Overgaard J. The relationship between carbon monoxide breathing, tumour oxygenation and local tumour control in the C3H mammary carcinoma in vivo. Br J Cancer. 1994;69:50–57. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1994.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grau C, Nordsmark M, Khalil AA, Horsman M, Overgaard J. Effect of carbon monoxide breathing on hypoxia and radiation response in the SCCVII tumor in vivo. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1994;29:449–454. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(94)90436-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nordsmark M, Maxwell RJ, Horsman MR, Bentzen SM, Overgaard J. The effect of hypoxia and hyperoxia on nucleoside triphosphate/inorganic phosphate, pO2 and radiation response in an experimental tumour model. Br J Cancer. 1997;76:1432–1439. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1997.575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vaupel P, Okunieff P, Kallinowski F, Neuringer LJ. Correlations between 31P NMR spectroscopy and tissue O2 tension measurements in a murine fibrosarcoma. Radiat Res. 1989;120:477–493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sostman HD, Rockwell S, Sylvia AL, Madwed D, Cofer G, Charles HC, Negro-Vilar R, Moore D. Evaluation of BA1112 rhabdomyosarcoma oxygenation with microelectrodes, optical spectrophotometry, radiosensitivity and magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Magn Reson Med. 1991;20:253–267. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910200208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arteel GE, Thurman RG, Yates JM, Raleigh JA. Evidence that hypoxia markers detect oxygen gradients in liver: pimonidazole and retrograde perfusion of rat liver. Br J Cancer. 1995;72:889–895. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1995.429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alati T, van Cleff M, Strom SC, Jirtle RL. Radiation sensitivity of adult human parenchymal hepatocytes. Radiat Res. 1988;115:152–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stubbs M, Rodrigues LM, Griffiths JR. Potential artefacts from overlying tissues in 31P NMR spectra of subcutaneously implanted rat tumours. NMR Biomed. 1989;1:165–170. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1940010403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Menke H, Vaupel P. Effect of injectable or inhalational anesthetics and of neuroleptic, neuroleptanalgesic and sedative agents on tumor blood flow. Radiat Res. 1988;114:64–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sansom PM, Wood PJ. 31P MRS of tumor metabolism in anaesthetized vs. conscious mice. NMR Biomed. 1994;7:167–171. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1940070403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gillies RJ, Liu Z, Bhujwalla ZM. 31P MRS measurements of extracellular pH of tumors using 3-aminopropylphosphonate. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:C195–C203. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.267.1.C195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van der Veen JWC, de Beer R, Luyten PR, van Ormondt D. Accurate quantification of in vivo 31P NMR signals using the variable projection method and prior knowledge. Magn Reson Med. 1988;6:92–98. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910060111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van den Boogaart A, Howe FA, Rodrigues LM, Stubbs M, Griffiths JR. In vivo 31P MRS: absolute concentrations, signal-to-noise and prior knowledge. NMR Biomed. 1995;8:87–93. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1940080207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCoy CL, Parkins CS, Chaplin DJ, Griffiths JR, Rodrigues LM, Stubbs M. The effect of blood flow modification on intra- and extracellular pH measured by 31P MRS in murine tumours. Br J Cancer. 1995;72:905–911. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1995.431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stubbs M, Robinson SP, Rodrigues LM, Parkins CS, Collingridge DR, Griffiths JR. The effects of host carbogen (95% O2/5% CO2) breathing on metabolic characteristics of Morris hepatoma 9618a. Br J Cancer. 1998;78:1449–1456. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wike-Hooley JL, Haveman J, Reinhold HS. The relevance of tumor pH to the treatment of malignant disease. Radiother Oncol. 1984;2:343–366. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(84)80077-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Frenzel T, Koßler S, Bauer H, Niedballa U, Weinmann HJ. Non-invasive in vivo pH measurements using a fluorinated pH probe and fluorine-19 magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Invest Radiol. 1994;29:S220–S222. doi: 10.1097/00004424-199406001-00073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thulborn KR, Waterton JC, Matthews PM, Radda GK. Oxygenation dependence of the transverse relaxation time of water protons in whole blood at high field. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1982;714:265–270. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(82)90333-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Howe FA, Robinson SP, Griffiths JR. Discrimination of blood flow and oxygenation changes in rat tumours in response to carbogen breathing. Proc Soc Magn Reson. 1995;1:64. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pauling L, Coryell CD. The magnetic properties and structure of hemoglobin, oxyhemoglobin and carbonmonoxyhemoglobin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1936;22:210–216. doi: 10.1073/pnas.22.4.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nordsmark M, Grau C, Horsman MR, Jorgensen HS, Overgaard J. Relationship between tumour oxygenation, bioenergetic status and radiobiological hypoxia in an experimental model. Acta Oncol. 1995;34:329–334. doi: 10.3109/02841869509093984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kallinowski F, Schlenger KH, Runkel S, Kloes M, Stohrer M, Okunieff P, Vaupel P. Blood flow, metabolism, cellular microenvironment and growth rate of human tumour xenografts. Cancer Res. 1989;49:3759–3764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Samsel RW, Cherqui D, Pietrabissa A, Sanders WM, Roncella M, Edmond JC, Schumacker PT. Hepatic oxygen and lactate extraction during stagnant hypoxia. J Appl Physiol. 1991;70:186–193. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1991.70.1.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mimura Y, Furuya K. Mechanism of adaptation to hypoxia in energy metabolism in rats. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;181:437–443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stratford IJ, Adams GE, Bremner JCM, Cole S, Edwards HS, Robertson N, Wood PJ. Manipulation and exploitation of the tumour environment for therapeutic benefit. Int J Radiat Biol Phys. 1994;65:85–94. doi: 10.1080/09553009414550121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]