Abstract

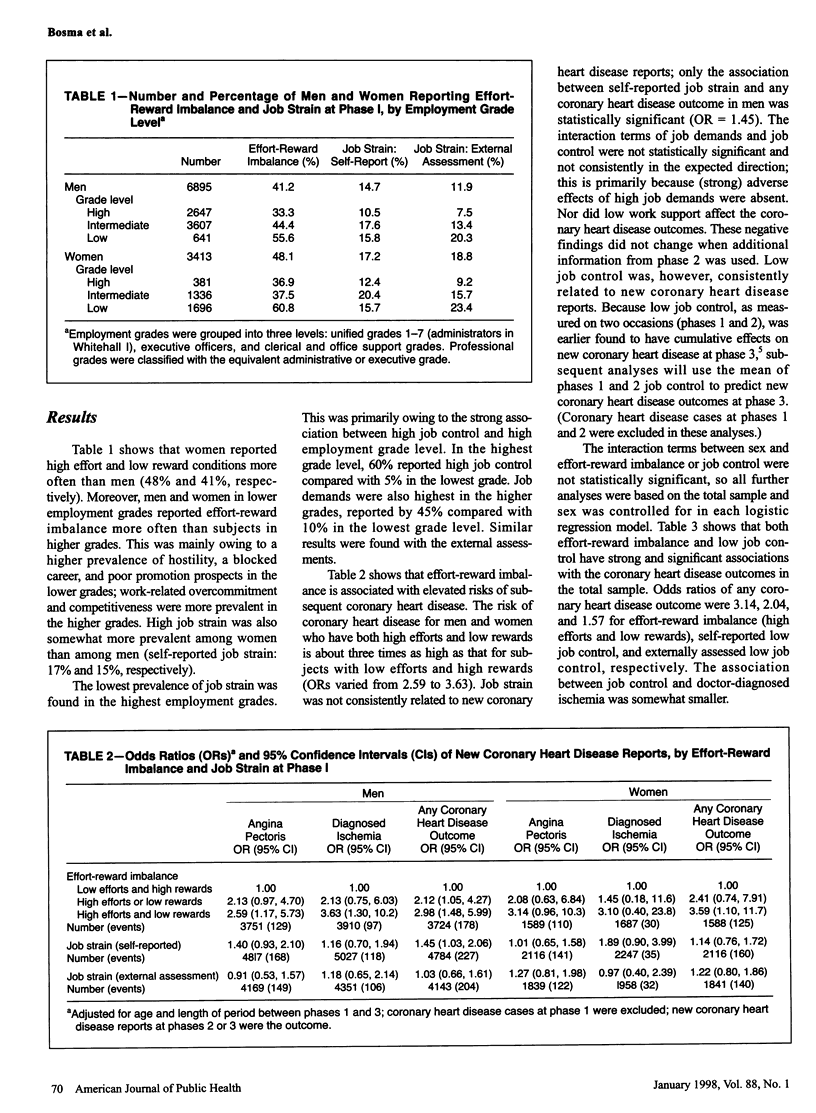

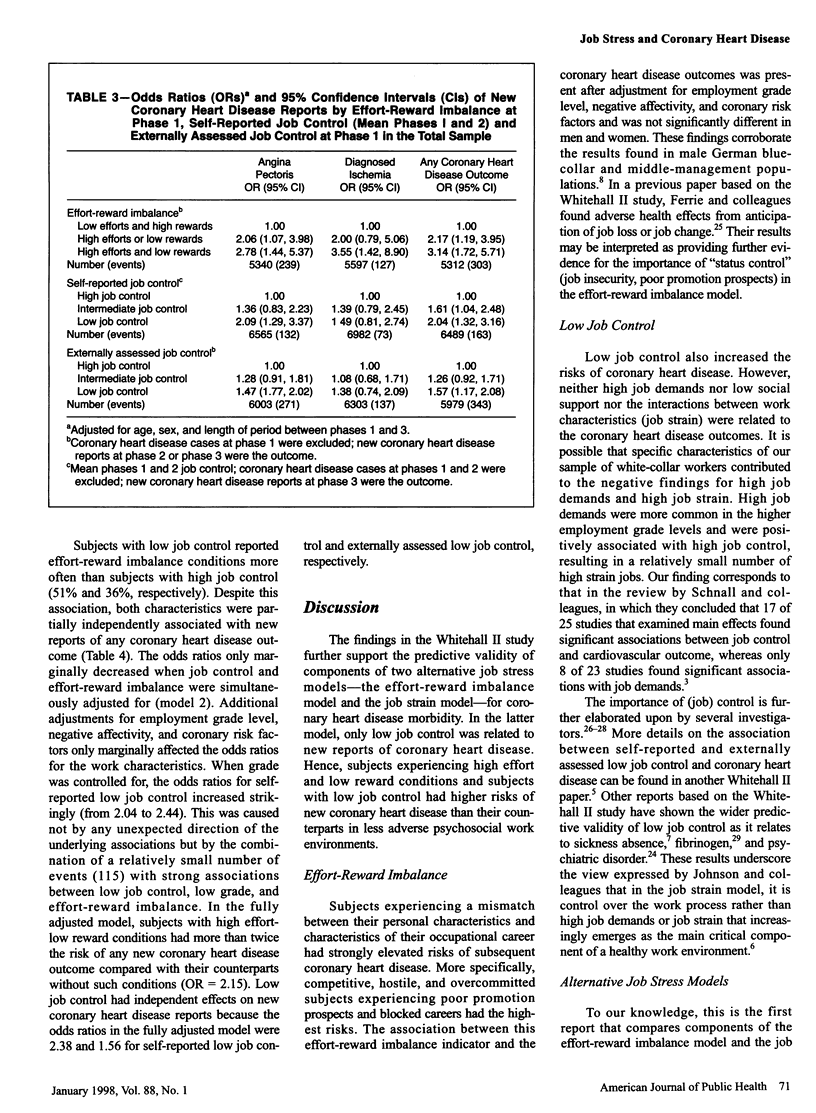

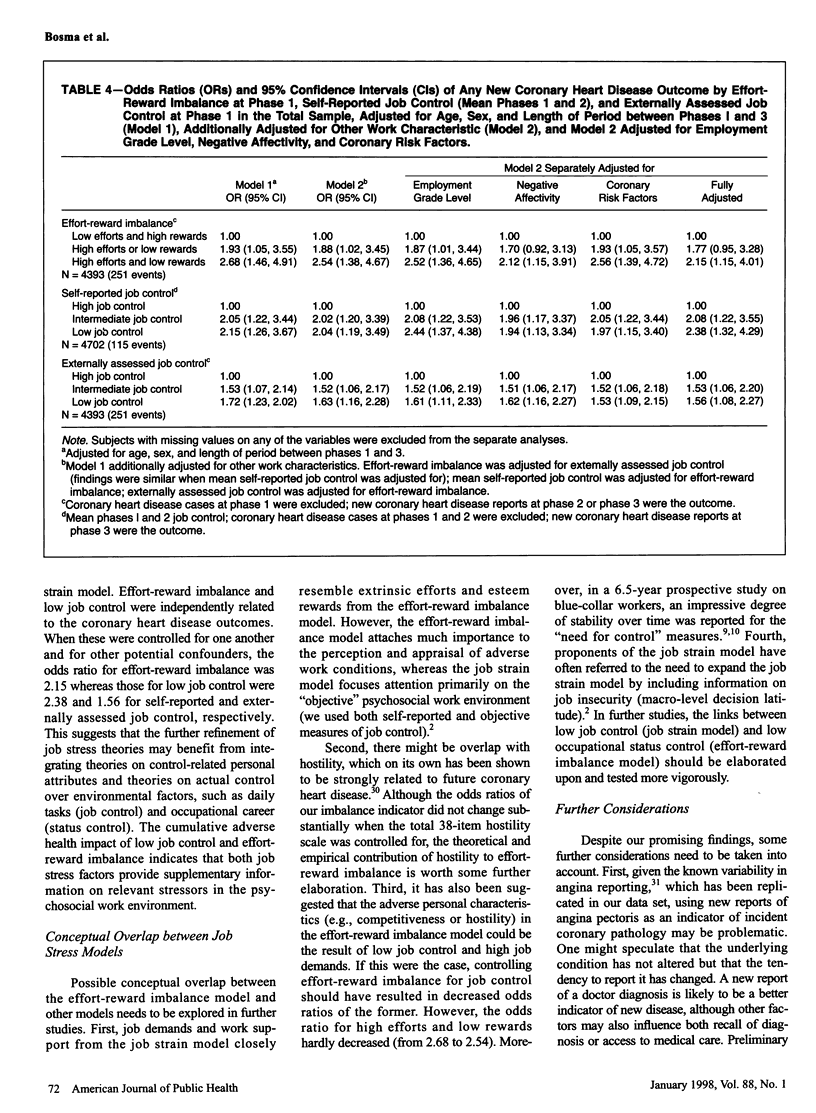

OBJECTIVES: This study examined the association between two alternative job stress models-the effort-reward imbalance model and the job strain model-and the risk of coronary heart disease among male and female British civil servants. METHODS: The logistic regression analyses were based on a prospective cohort study (Whitehall II study) comprising 6895 men and 3413 women aged 35 to 55 years. Baseline measures of both job stress models were related to new reports of coronary heart disease over a mean 5.3 years of follow-up. RESULTS: The imbalance between personal efforts (competitiveness, work-related overcommitment, and hostility) and rewards (poor promotion prospects and a blocked career') was associated with a 2.15-fold higher risk of new coronary heart disease. Job strain and high job demands were not related to coronary heart disease; however, low job control was strongly associated with new disease. The odds ratios for low job control were 2.38 and 1.56 for self-reported and externally assessed job control, respectively. Work characteristics were simultaneously adjusted and controlled for employment grade level, negative affectivity, and coronary risk factors. CONCLUSIONS: This is apparently the first report showing independent effects of components of two alternative job stress models-the effort-reward imbalance model and the job strain model (job control only)-on coronary heart disease.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Alterman T., Shekelle R. B., Vernon S. W., Burau K. D. Decision latitude, psychologic demand, job strain, and coronary heart disease in the Western Electric Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1994 Mar 15;139(6):620–627. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosma H., Marmot M. G., Hemingway H., Nicholson A. C., Brunner E., Stansfeld S. A. Low job control and risk of coronary heart disease in Whitehall II (prospective cohort) study. BMJ. 1997 Feb 22;314(7080):558–565. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7080.558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brief A. P., Burke M. J., George J. M., Robinson B. S., Webster J. Should negative affectivity remain an unmeasured variable in the study of job stress? J Appl Psychol. 1988 May;73(2):193–198. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.73.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner E., Davey Smith G., Marmot M., Canner R., Beksinska M., O'Brien J. Childhood social circumstances and psychosocial and behavioural factors as determinants of plasma fibrinogen. Lancet. 1996 Apr 13;347(9007):1008–1013. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)90147-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P. Y., Spector P. E. Negative affectivity as the underlying cause of correlations between stressors and strains. J Appl Psychol. 1991 Jun;76(3):398–407. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.76.3.398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrie J. E., Shipley M. J., Marmot M. G., Stansfeld S., Smith G. D. Health effects of anticipation of job change and non-employment: longitudinal data from the Whitehall II study. BMJ. 1995 Nov 11;311(7015):1264–1269. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7015.1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frese M. Stress at work and psychosomatic complaints: a causal interpretation. J Appl Psychol. 1985 May;70(2):314–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes S. G., Levine S., Scotch N., Feinleib M., Kannel W. B. The relationship of psychosocial factors to coronary heart disease in the Framingham study. I. Methods and risk factors. Am J Epidemiol. 1978 May;107(5):362–383. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J. V., Stewart W., Hall E. M., Fredlund P., Theorell T. Long-term psychosocial work environment and cardiovascular mortality among Swedish men. Am J Public Health. 1996 Mar;86(3):324–331. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.3.324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karasek R., Baker D., Marxer F., Ahlbom A., Theorell T. Job decision latitude, job demands, and cardiovascular disease: a prospective study of Swedish men. Am J Public Health. 1981 Jul;71(7):694–705. doi: 10.2105/ajph.71.7.694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasl S. V. The challenge of studying the disease effects of stressful work conditions. Am J Public Health. 1981 Jul;71(7):682–684. doi: 10.2105/ajph.71.7.682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasl S. V. The influence of the work environment on cardiovascular health: a historical, conceptual, and methodological perspective. J Occup Health Psychol. 1996 Jan;1(1):42–56. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.1.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmot M. G., Bosma H., Hemingway H., Brunner E., Stansfeld S. Contribution of job control and other risk factors to social variations in coronary heart disease incidence. Lancet. 1997 Jul 26;350(9073):235–239. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)04244-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmot M. G., Smith G. D., Stansfeld S., Patel C., North F., Head J., White I., Brunner E., Feeney A. Health inequalities among British civil servants: the Whitehall II study. Lancet. 1991 Jun 8;337(8754):1387–1393. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)93068-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller T. Q., Smith T. W., Turner C. W., Guijarro M. L., Hallet A. J. A meta-analytic review of research on hostility and physical health. Psychol Bull. 1996 Mar;119(2):322–348. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.119.2.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North F. M., Syme S. L., Feeney A., Shipley M., Marmot M. Psychosocial work environment and sickness absence among British civil servants: the Whitehall II study. Am J Public Health. 1996 Mar;86(3):332–340. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.3.332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose G., Hamilton P. S., Keen H., Reid D. D., McCartney P., Jarrett R. J. Myocardial ischaemia, risk factors and death from coronary heart-disease. Lancet. 1977 Jan 15;1(8003):105–109. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(77)91701-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose G. Variability of angina. Some implications for epidemiology. Br J Prev Soc Med. 1968 Jan;22(1):12–15. doi: 10.1136/jech.22.1.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnall P. L., Landsbergis P. A., Baker D. Job strain and cardiovascular disease. Annu Rev Public Health. 1994;15:381–411. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.15.050194.002121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegrist J. Adverse health effects of high-effort/low-reward conditions. J Occup Health Psychol. 1996 Jan;1(1):27–41. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.1.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegrist J., Peter R., Junge A., Cremer P., Seidel D. Low status control, high effort at work and ischemic heart disease: prospective evidence from blue-collar men. Soc Sci Med. 1990;31(10):1127–1134. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(90)90234-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stansfeld S. A., North F. M., White I., Marmot M. G. Work characteristics and psychiatric disorder in civil servants in London. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1995 Feb;49(1):48–53. doi: 10.1136/jech.49.1.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]