Abstract

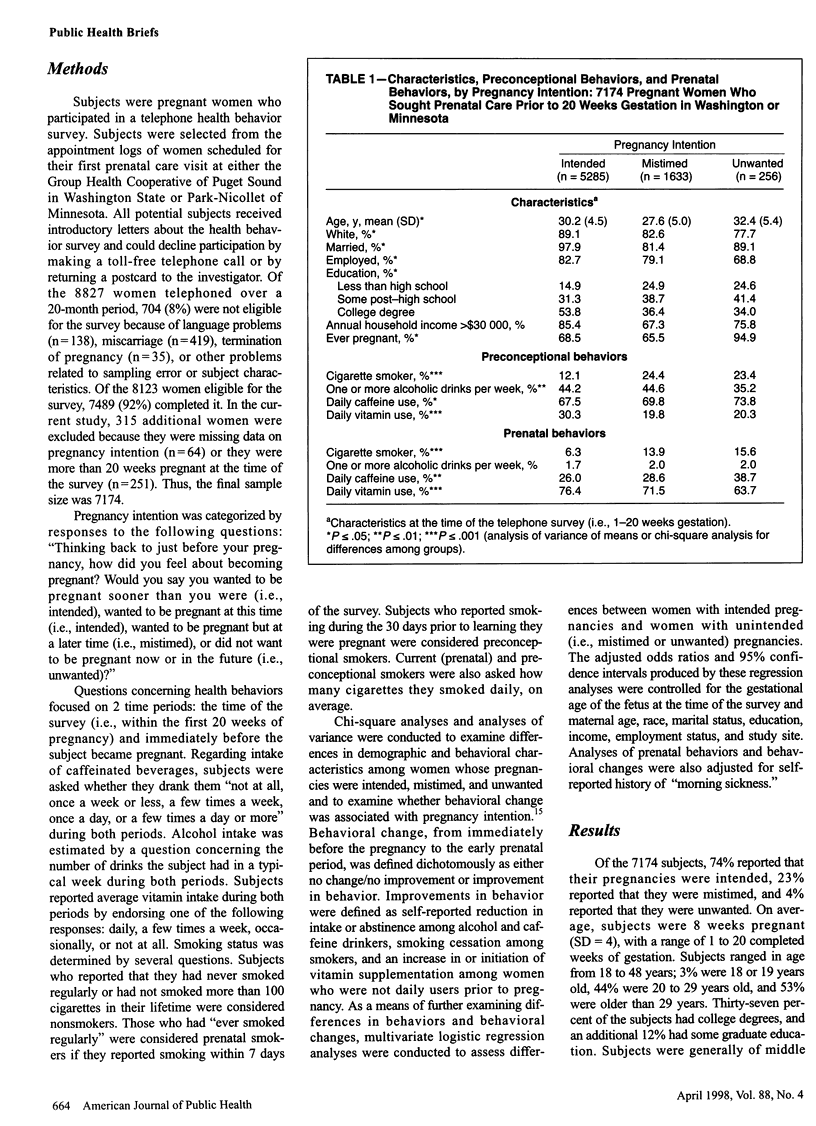

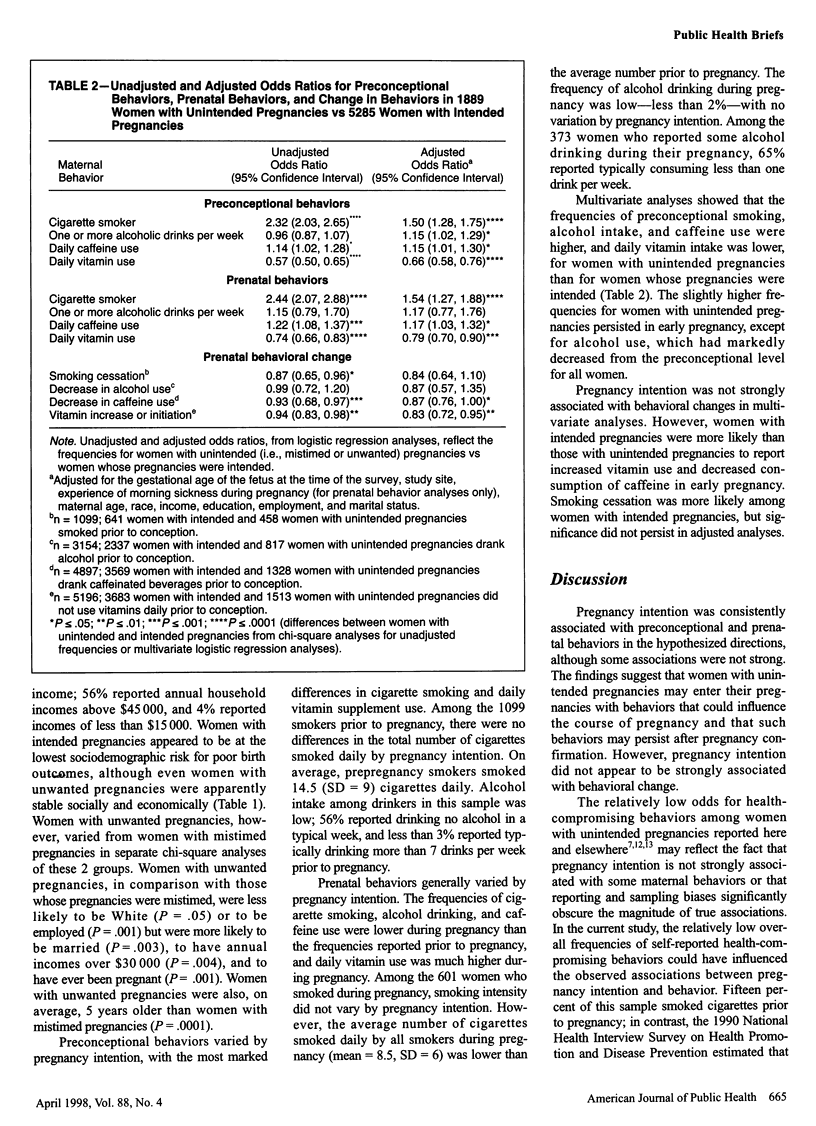

OBJECTIVES: This study examined whether pregnancy intention was associated with cigarette smoking, alcohol drinking, use of vitamins, and consumption of caffeinated drinks prior to pregnancy and in early pregnancy. METHODS: Data from a telephone survey of 7174 pregnant women were analyzed. RESULTS: In comparison with women whose pregnancies were intended, women with unintended pregnancies were more likely to report cigarette smoking and less likely to report daily vitamin use. Women with unintended pregnancies were also less likely to decrease consumption of caffeinated beverages or increase daily vitamin use. CONCLUSIONS: Pregnancy intention was associated with health behaviors, prior to pregnancy and in early pregnancy, that may influence pregnancy course and birth outcomes.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bustan M. N., Coker A. L. Maternal attitude toward pregnancy and the risk of neonatal death. Am J Public Health. 1994 Mar;84(3):411–414. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.3.411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright A. Unintended pregnancies that lead to babies. Soc Sci Med. 1988;27(3):249–254. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(88)90128-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrest J. D. Epidemiology of unintended pregnancy and contraceptive use. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994 May;170(5 Pt 2):1485–1489. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(94)05008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyce T. J., Grossman M. Pregnancy wantedness and the early initiation of prenatal care. Demography. 1990 Feb;27(1):1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kost K., Forrest J. D. Intention status of U.S. births in 1988: differences by mothers' socioeconomic and demographic characteristics. Fam Plann Perspect. 1995 Jan-Feb;27(1):11–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick M. C., Brooks-Gunn J., Shorter T., Wallace C. Y., Holmes J. H., Heagarty M. C. The planning of pregnancy among low-income women in central Harlem. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1987 Jan;156(1):145–149. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(87)90226-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parazzini F., Davoli E., Rabaiotti M., Restelli S., Stramare L., Dindelli M., La Vecchia C., Fanelli R. Validity of self-reported smoking habits in pregnancy: a saliva cotinine analysis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1996 Apr;75(4):352–354. doi: 10.3109/00016349609033330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma R., Synkewecz C., Raggio T., Mattison D. R. Intermediate variables as determinants of adverse pregnancy outcome in high-risk inner-city populations. J Natl Med Assoc. 1994 Nov;86(11):857–860. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weller R. H., Eberstein I. W., Bailey M. Pregnancy wantedness and maternal behavior during pregnancy. Demography. 1987 Aug;24(3):407–412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]