Abstract

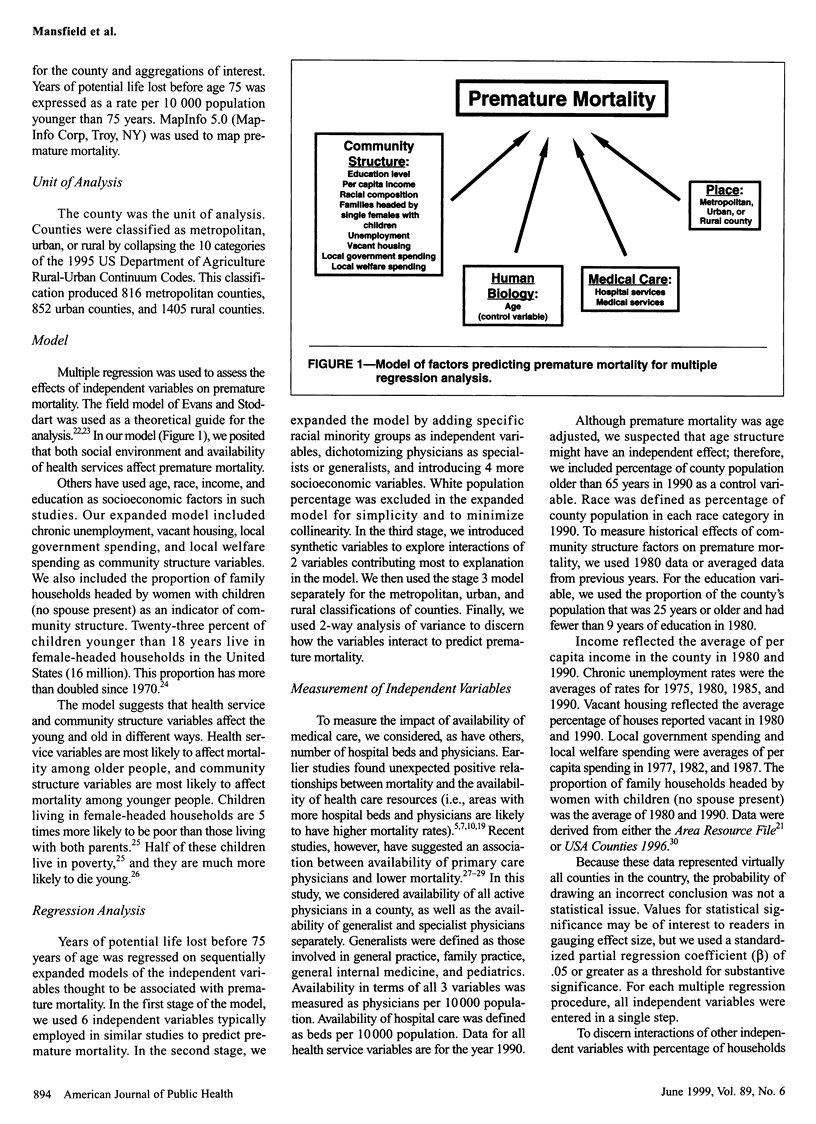

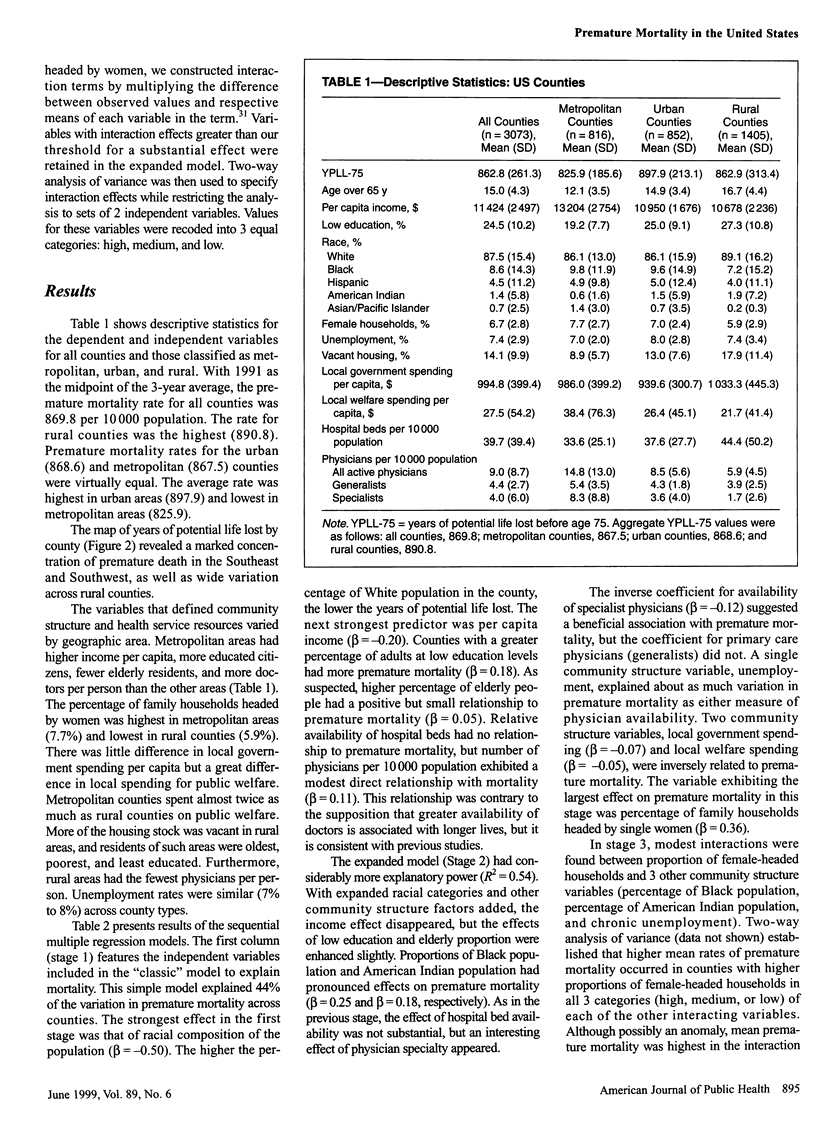

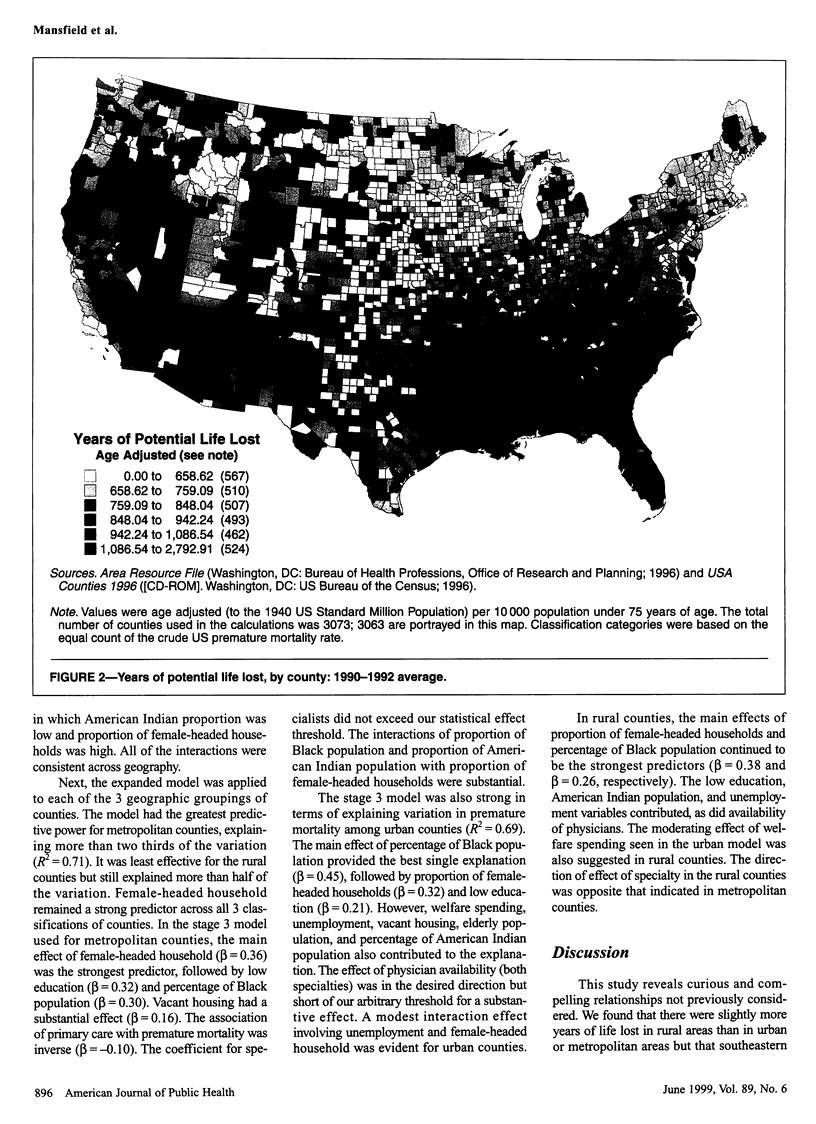

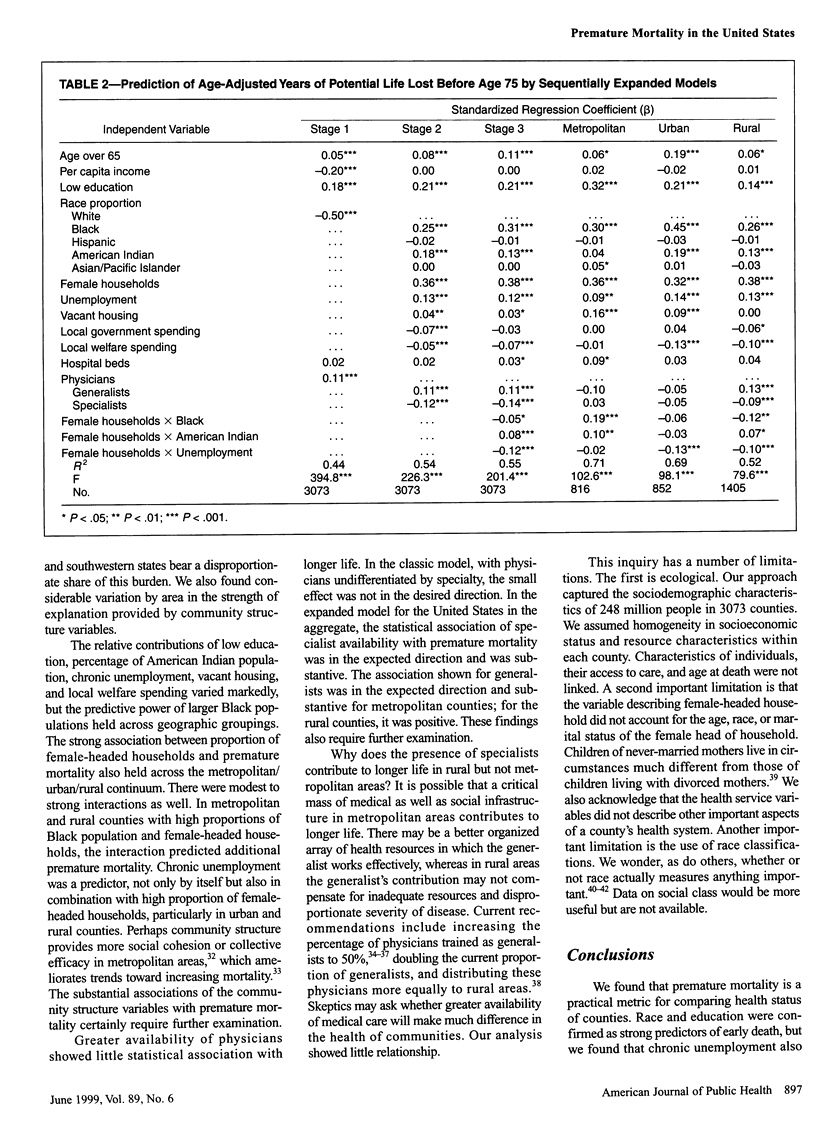

OBJECTIVES: This study examined premature mortality by county in the United States and assessed its association with metro/urban/rural geographic location, socioeconomic status, household type, and availability of medical care. METHODS: Age-adjusted years of potential life lost before 75 years of age were calculated and mapped by county. Predictors of premature mortality were determined by multiple regression analysis. RESULTS: Premature mortality was greatest in rural counties in the Southeast and Southwest. In a model predicting 55% of variation across counties, community structure factors explained more than availability of medical care. The proportions of female-headed households and Black populations were the strongest predictors, followed by variables measuring low education, American Indian population, and chronic unemployment. Greater availability of generalist physicians predicted fewer years of life lost in metropolitan counties but more in rural counties. CONCLUSIONS: Community structure factors statistically explain much of the variation in premature mortality. The degree to which premature mortality is predicted by percentage of female-headed households is important for policy-making and delivery of medical care. The relationships described argue strongly for broadening the biomedical model.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Antonovsky A. Social class, life expectancy and overall mortality. Milbank Mem Fund Q. 1967 Apr;45(2):31–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhopal R., Donaldson L. White, European, Western, Caucasian, or what? Inappropriate labeling in research on race, ethnicity, and health. Am J Public Health. 1998 Sep;88(9):1303–1307. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.9.1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird S. T., Bauman K. E. The relationship between structural and health services variables and state-level infant mortality in the United States. Am J Public Health. 1995 Jan;85(1):26–29. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.1.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duleep H. O. Measuring socioeconomic mortality differentials over time. Demography. 1989 May;26(2):345–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer F. L., Stokes C. S., Fiser R. H., Papini D. P. Poverty, primary care and age-specific mortality. J Rural Health. 1991 Spring;7(2):153–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.1991.tb00716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman J. J., Makuc D. M., Kleinman J. C., Cornoni-Huntley J. National trends in educational differentials in mortality. Am J Epidemiol. 1989 May;129(5):919–933. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finney J. W., Mitchell R. E., Cronkite R. C., Moos R. H. Methodological issues in estimating main and interactive effects: examples from coping/social support and stress field. J Health Soc Behav. 1984 Mar;25(1):85–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fullilove M. T. Comment: abandoning "race" as a variable in public health research--an idea whose time has come. Am J Public Health. 1998 Sep;88(9):1297–1298. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.9.1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House J. S., Lepkowski J. M., Kinney A. M., Mero R. P., Kessler R. C., Herzog A. R. The social stratification of aging and health. J Health Soc Behav. 1994 Sep;35(3):213–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmot M. G., Kogevinas M., Elston M. A. Social/economic status and disease. Annu Rev Public Health. 1987;8:111–135. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.08.050187.000551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newhouse J. P., Friedlander L. J. The relationship between medical resources and measures of health: some additional evidence. J Hum Resour. 1980 Winter;15(2):200–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappas G., Queen S., Hadden W., Fisher G. The increasing disparity in mortality between socioeconomic groups in the United States, 1960 and 1986. N Engl J Med. 1993 Jul 8;329(2):103–109. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199307083290207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivo M. L., Henderson T. M., Jackson D. M. State legislative strategies to improve the supply and distribution of generalist physicians, 1985 to 1992. Am J Public Health. 1995 Mar;85(3):405–407. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.3.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson R. J., Raudenbush S. W., Earls F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: a multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science. 1997 Aug 15;277(5328):918–924. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L. Primary care, specialty care, and life chances. Int J Health Serv. 1994;24(3):431–458. doi: 10.2190/BDUU-J0JD-BVEX-N90B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L. The relationship between primary care and life chances. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 1992 Fall;3(2):321–335. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh G. K., Yu S. M. US childhood mortality, 1950 through 1993: Trends and socioeconomic diffferentials. Am J Public Health. 1996 Apr;86(4):505–512. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.4.505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith G. D., Bartley M., Blane D. The Black report on socioeconomic inequalities in health 10 years on. BMJ. 1990 Aug 18;301(6748):373–377. doi: 10.1136/bmj.301.6748.373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D. R., Lavizzo-Mourey R., Warren R. C. The concept of race and health status in America. Public Health Rep. 1994 Jan-Feb;109(1):26–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]