Abstract

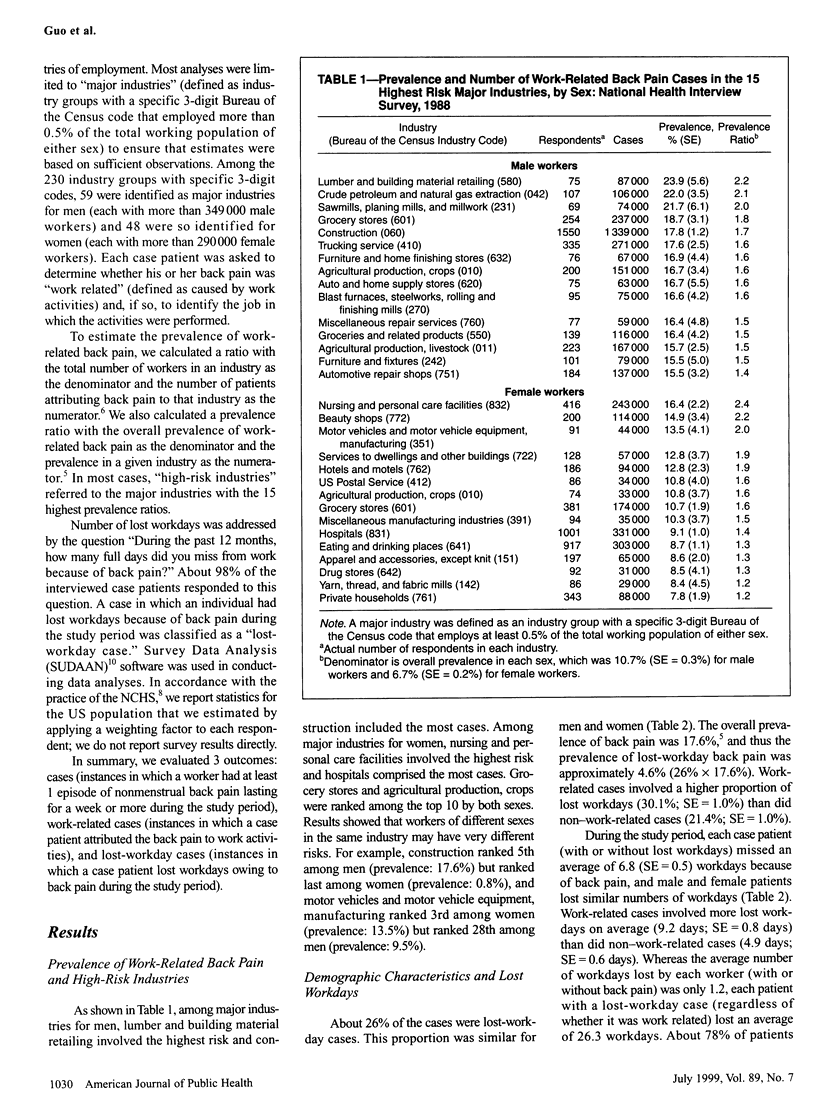

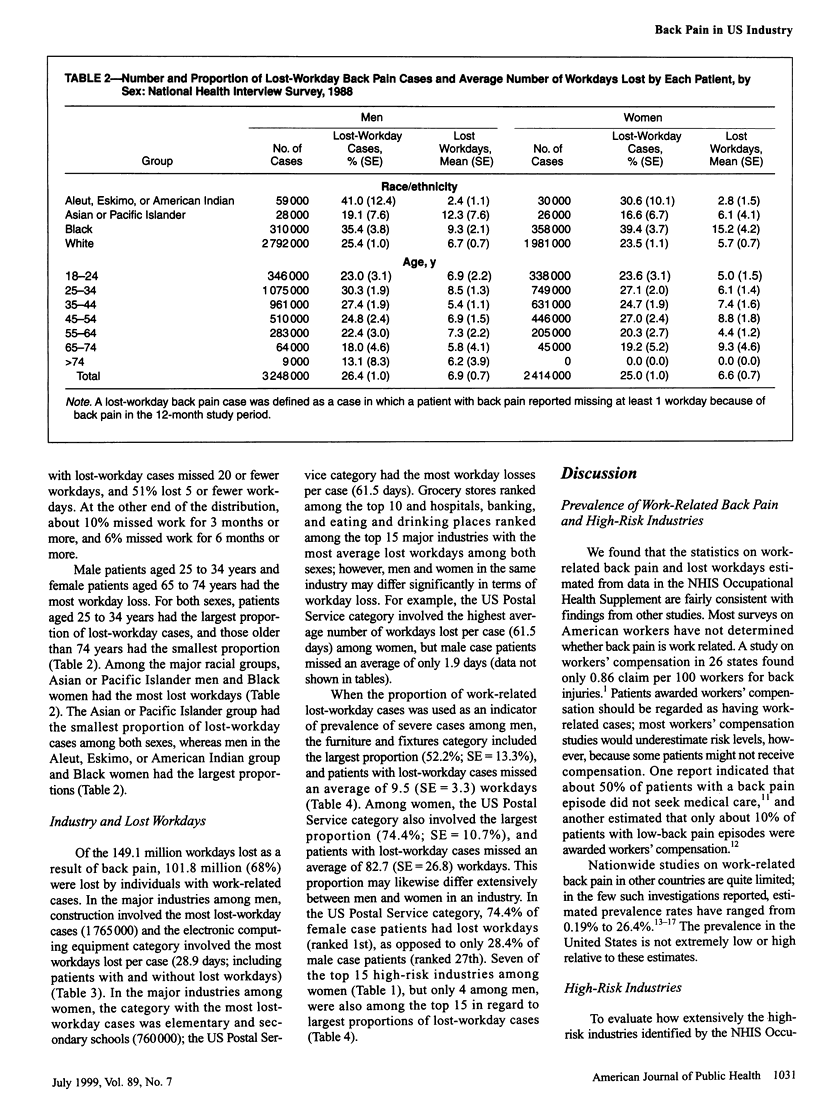

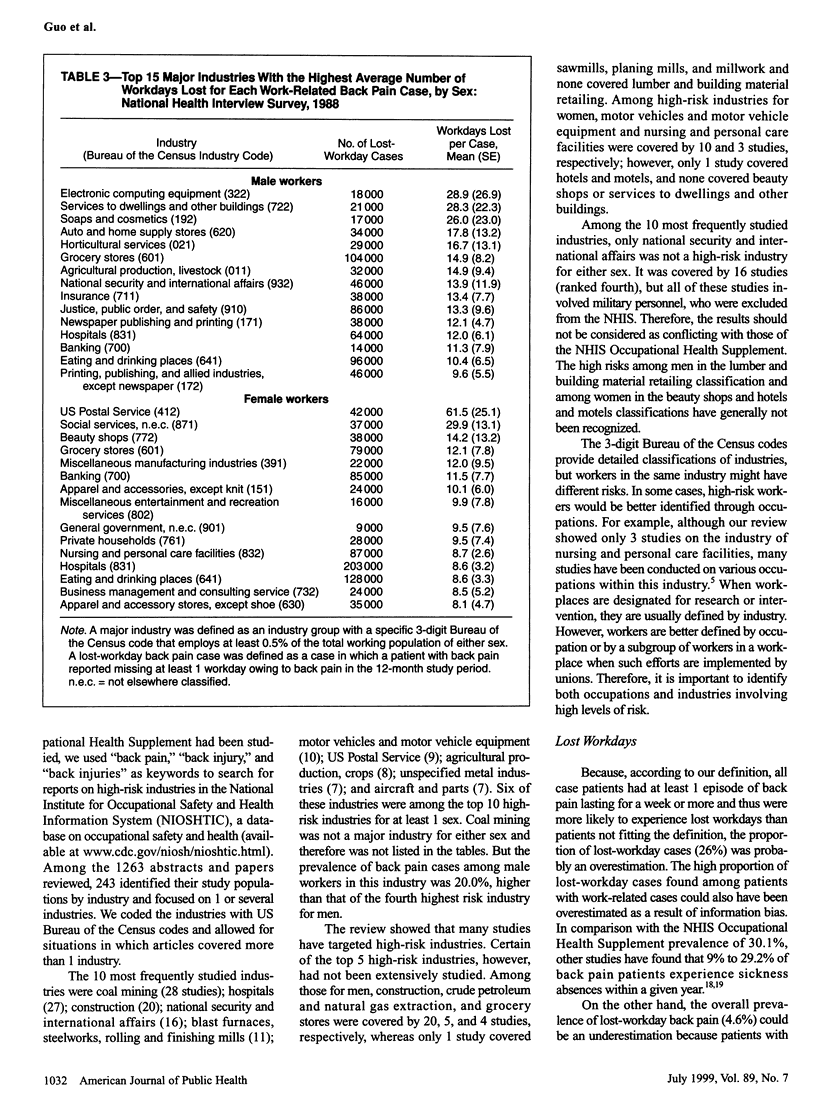

OBJECTIVES: Back pain is the most common reason for filing workers' compensation claims and often causes lost workdays. Data from the 1988 National Health Interview Survey were analyzed to identify high-risk industries and to estimate the prevalence of work-related back pain and number of workdays lost. METHODS: Analyses included 30074 respondents who worked during the 12 months before the interview. A case patient was defined as a respondent who had back pain every day for a week or more during that period. RESULTS: The prevalence of lost-workday back pain was 4.6%, and individuals with work-related cases lost 101.8 million workdays owing to back pain. Male and female case patients lost about the same number of workdays. Industries in high-risk categories were also identified for future research and intervention, including those seldom studied. CONCLUSIONS: This study provides statistically reliable national estimates of the prevalence of back pain among workers and the enormous effect of this condition on American industry in terms of lost workdays.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Abenhaim L., Suissa S. Importance and economic burden of occupational back pain: a study of 2,500 cases representative of Quebec. J Occup Med. 1987 Aug;29(8):670–674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson J. A. Epidemiological aspects of back pain. J Soc Occup Med. 1986 Autumn;36(3):90–94. doi: 10.1093/occmed/36.3.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson J. A. Shoulder pain and tension neck and their relation to work. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1984 Dec;10(6 Spec No):435–442. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.2300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson G. B. Epidemiologic aspects on low-back pain in industry. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1981 Jan-Feb;6(1):53–60. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198101000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biering-Sørensen F. Low back trouble in a general population of 30-, 40-, 50-, and 60-year-old men and women. Study design, representativeness and basic results. Dan Med Bull. 1982 Oct;29(6):289–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burry H. C., Gravis V. Compensated back injury in New Zealand. N Z Med J. 1988 Aug 24;101(852):542–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaffin D. B. Manual materials handling: the cause of over-exertion injury and illness in industry. J Environ Pathol Toxicol. 1979 May-Jun;2(5):31–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. E., Goel V., Frank J. W., Gibson E. S. Predicting risk of back injuries, work absenteeism, and chronic disability. The shortcomings of preplacement screening. J Occup Med. 1994 Oct;36(10):1093–1099. doi: 10.1097/00043764-199410000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham L. S., Kelsey J. L. Epidemiology of musculoskeletal impairments and associated disability. Am J Public Health. 1984 Jun;74(6):574–579. doi: 10.2105/ajph.74.6.574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deyo R. A., Tsui-Wu Y. J. Descriptive epidemiology of low-back pain and its related medical care in the United States. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1987 Apr;12(3):264–268. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198704000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donchin M., Woolf O., Kaplan L., Floman Y. Secondary prevention of low-back pain. A clinical trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1990 Dec;15(12):1317–1320. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199012000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldstein A., Valanis B., Vollmer W., Stevens N., Overton C. The Back Injury Prevention Project pilot study. Assessing the effectiveness of back attack, an injury prevention program among nurses, aides, and orderlies. J Occup Med. 1993 Feb;35(2):114–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzler S. L., Berger R. A. Attitudinal change: the Chelsea back program. Occup Health Saf. 1982 Feb;51(2):24–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frymoyer J. W., Cats-Baril W. L. An overview of the incidences and costs of low back pain. Orthop Clin North Am. 1991 Apr;22(2):263–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg A., Owen B. Reducing back stress to nursing personnel: an ergonomic intervention in a nursing home. Ergonomics. 1992 Nov;35(11):1353–1375. doi: 10.1080/00140139208967398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H. R., Tanaka S., Cameron L. L., Seligman P. J., Behrens V. J., Ger J., Wild D. K., Putz-Anderson V. Back pain among workers in the United States: national estimates and workers at high risk. Am J Ind Med. 1995 Nov;28(5):591–602. doi: 10.1002/ajim.4700280504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyntelberg F. One year incidence of low back pain among male residents of Copenhagen aged 40-59. Dan Med Bull. 1974 Mar;21(1):30–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein B. P., Jensen R. C., Sanderson L. M. Assessment of workers' compensation claims for back strains/sprains. J Occup Med. 1984 Jun;26(6):443–448. doi: 10.1097/00043764-198406000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalich N. R., Sestito J. P. Occupational health surveillance: contributions from the National Health Interview Survey. Am J Ind Med. 1997 Jan;31(1):1–3. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0274(199701)31:1<1::aid-ajim1>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leavitt S. S., Johnston T. L., Beyer R. D. The process of recovery: patterns in industrial back injury. 1. Costs and other quantitative measures of effort. IMS Ind Med Surg. 1971 Nov;40(8):7–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigh J. P., Sheetz R. M. Prevalence of back pain among fulltime United States workers. Br J Ind Med. 1989 Sep;46(9):651–657. doi: 10.1136/oem.46.9.651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard S. A. The role of exercise and posture in preventing low back injury. AAOHN J. 1990 Jul;38(7):318–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liira J. P., Shannon H. S., Chambers L. W., Haines T. A. Long-term back problems and physical work exposures in the 1990 Ontario Health Survey. Am J Public Health. 1996 Mar;86(3):382–387. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.3.382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magora A., Taustein I. An investigation of the problem of sick-leave in the patient suffering from low back pain. IMS Ind Med Surg. 1969 Nov;38(11):398–408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGill C. M. Industrial back problems. A control program. J Occup Med. 1968 Apr;10(4):174–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisbord L. S., Greenland S. Factors associated with self-reported back-pain prevalence: a population-based study. J Chronic Dis. 1985;38(8):691–702. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(85)90023-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stubbs D. Ergonomics and back pain. Occup Health (Lond) 1991 Mar;43(3):82–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svane O. National prevention of musculoskeletal workplace injury: Denmark--a summary. Ergonomics. 1987 Feb;30(2):181–184. doi: 10.1080/00140138708969691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]