Abstract

TGF-βs play diverse and complex roles in many biological processes. In tumorigenesis, they can function either as tumor suppressors or as pro-oncogenic factors, depending on the stage of the disease. We have developed transgenic mice expressing a TGF-β antagonist of the soluble type II TGF-β receptor:Fc fusion protein class, under the regulation of the mammary-selective MMTV-LTR promoter/enhancer. Biologically significant levels of antagonist were detectable in the serum and most tissues of this mouse line. The mice were resistant to the development of metastases at multiple organ sites when compared with wild-type controls, both in a tail vein metastasis assay using isogenic melanoma cells and in crosses with the MMTV-neu transgenic mouse model of metastatic breast cancer. Importantly, metastasis from endogenous mammary tumors was suppressed without any enhancement of primary tumorigenesis. Furthermore, aged transgenic mice did not exhibit the severe pathology characteristic of TGF-β null mice, despite lifetime exposure to the antagonist. The data suggest that in vivo the antagonist may selectively neutralize the undesirable TGF-β associated with metastasis, while sparing the regulatory roles of TGF-βs in normal tissues. Thus this soluble TGF-β antagonist has potential for long-term clinical use in the prevention of metastasis.

Introduction

TGF-βs are multifunctional growth factors that regulate development, functional and proliferative homeostasis, and response to environmental challenge (1). The central importance of these growth factors in humans is underscored by the fact that many disease processes are associated with aberrant TGF-β function. Loss of normal TGF-β function has been implicated in the pathogenesis of cancer, atherosclerosis, and autoimmune and inflammatory diseases, while excessive TGF-β production has been implicated in fibroproliferative disorders, immunosuppression, successful parasite infection, and metastasis (2–9).

The role of TGF-βs in tumorigenesis is particularly complex. Clinical and mouse model data show that the TGF-β system can clearly function as a tumor suppressor pathway, and reduction or loss of TGF-β receptors or downstream signaling components is seen in many human tumors (for reviews, see refs. 2–5). However, late-stage human tumors frequently show a paradoxical increase in expression of TGF-βs that is associated with increased metastasis and poor prognosis (10). The current rationalization for these observations is that TGF-βs function as tumor suppressors early in tumorigenesis when epithelial cell responsiveness to TGF-β is still relatively normal. Later in the process, genetic or epigenetic alterations in multiple pathways compromise the tumor suppressor activity, and the TGF-βs then function predominantly as oncogenes to promote the progression to aggressive metastatic disease (2).

Ideally in a clinical setting, one would want to selectively neutralize the TGF-β that is involved in disease pathogenesis without affecting the normal protective and homeostatic roles of TGF-β in unaffected tissue. TGF-β antagonists of various types have been used successfully to ameliorate TGF-β–driven lesions, especially fibrosis, in animal models (11–16). However, most of these studies have been short-term, or have involved local delivery of the antagonist. The consequences of long-term systemic exposure to high-affinity TGF-β antagonists have not been assessed, particularly regarding the likelihood of increased spontaneous tumorigenesis and immune system dysfunction, as would be predicted from the phenotypes of the TGF-β1 null mouse (17–19).

Fusion of the extracellular ligand-binding domain of the type II TGF-β receptor to the Fc domain of human IgG1 gives a particularly high-affinity, stable TGF-β antagonist herein referred to as SR2F (20). Other cytokine antagonists of this soluble receptor:Fc fusion protein class have already proven to be clinically useful, as evidenced by the recent approval of the TNF-α antagonist etanercept for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (21). In the present work, we have generated a transgenic mouse model that has widespread expression of the SR2F TGF-β antagonist throughout its lifetime, and we show that the mice are protected against experimental metastasis without significant adverse side effects. The data suggest that this antagonist may be capable in vivo of selectively neutralizing the undesirable TGF-β that is associated with metastasis, while not affecting the TGF-β that is involved in maintenance of normal homeostasis.

Methods

Generation of SR2F transgenic mice.

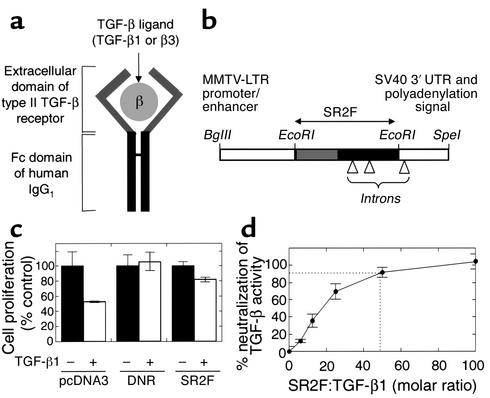

The SR2F TGF-β antagonist comprises the extracellular domain of the human type II TGF-β receptor fused to the Fc domain of human IgG1 (Figure 1a). Plasmid JP109-6, containing a form of the SR2F cDNA with two small introns in the Fc domain for enhanced expression in vivo, was obtained from Monica Tsang (R&D Systems Inc., Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA). The SR2F insert was subcloned into the pSKMMTV-SVPA vector (22) to generate a transgene in which the SR2F coding sequence is flanked by the MMTV-LTR promoter-enhancer and the SV40 3′ UTR and polyadenylation signal on excision with BglII and Spe1 (Figure 1b). The transgene was injected into the pronuclei of inbred FVB/NCr zygotes (23). Six founders were obtained, of which five showed germline transmission and two expressed the transgene. The higher-expressing line (MMTV-SR2F) was bred to homozygosity for further analysis. Age- and sex-matched wild-type FVB/NCr mice were used as controls. Mice were housed in an Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care accredited facility under conditions that met or exceeded NIH guidelines.

Figure 1.

Antagonist design and in vitro validation. (a) Soluble TGF-β antagonist SR2F. This antagonist consists of the extracellular domain of the human type II TGF-β receptor fused to the Fc domain of human IgG1. It can bind TGF-β1 and TGF-β3, but not TGF-β2. (b) Transgene construct. Transgene expression is driven by the mammary-selective MMTV-LTR promoter/enhancer. Small introns are present in the Fc domain of SR2F and the SV40 3′ UTR to enhance transgene expression in vivo. (c) Reversal of the growth-inhibiting effects of TGF-β1 by transfected SR2F. MDA MB435 cells stably transfected with empty vector (pcDNA3), membrane-bound dominant-negative type II TGF-β receptor (DNR), or SR2F were assayed for their resistance to the growth-inhibiting effects of added TGF-β1 (5 ng/ml). Cell proliferation is normalized to the “no TGF-β” condition for each construct. Results are the mean ± SD of three determinations. (d) Determination of the molar ratio of purified SR2F to TGF-β1 required for neutralization of TGF-β activity. The ability of increasing amounts of purified SR2F to reverse the growth-inhibiting activity of 2 pM TGF-β1 on Mv1Lu cells was determined. Results are the mean ± SD for three determinations.

Stable transfections and growth inhibition assays.

For high-level expression in vitro, the SR2F insert was subcloned into pcDNA3 (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, California, USA). The human breast cancer cell line MDA MB435 (gift of Stephen Byers, Lombardi Institute, Washington, DC, USA) was stably transfected with pcDNA3 vector alone, pcDNA3-SR2F, or pcDNA3-DNR, where DNR is a membrane-bound dominant-negative form of the type II TGF-β receptor (24). For growth inhibition assays, transfected cells were seeded at 105 cells/well in 24-well plates in DMEM with 10% FBS. After 24 hours, the cells were switched to assay medium containing DMEM, 0.1% FBS, and 10 ng/ml EGF, and allowed to condition the medium for 24 hours prior to the addition of 5 ng/ml TGF-β1 (R&D Systems Inc.) or vehicle control. After a further 22 hours, cells were pulsed with 3H-thymidine for 2 hours and harvested (25). For determining the molar ratio of SR2F to TGF-β — required to neutralize the growth-inhibiting effects of TGF-β — the highly sensitive Mv1Lu cell line was used (American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, Maryland, USA). TGF-β1 (2 pM) was present in all wells, with or without 0–200 pM purified SR2F protein (R&D Systems Inc.).

Northern blots and in situ hybridization.

RNA was extracted from tissues using Trizol reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Life Technologies Inc., Gaithersburg, Maryland, USA). Fifteen micrograms of total RNA were loaded per lane, and blots were hybridized with a 520-bp 32P-labeled probe specific for the Fc domain of SR2F. Ethidium bromide–stained ribosomal bands were visualized to access uniformity of RNA loading. The probe was generated by PCR amplification using the primer pair 5′-CGAAGACCCTGAGGTCAAGT-3′ (forward) and 5′-GAGGCTCTTCTGCGTGTAG-3′ (reverse), and was cloned into the pCR2.1 vector (Invitrogen Corp.). In situ hybridization was performed on paraformaldehyde-fixed tissue sections. The same Fc-specific probe was transcribed using Genius Kit 4 (Boehringer Mannheim Biochemicals Inc., Indianapolis, Indiana, USA) to generate sense and antisense probes. Hybridization of slides using digoxygenin-labeled probes was performed as previously described (26). Slides were counterstained with nuclear fast red.

SR2F ELISA.

A sensitive and specific ELISA for quantitation of SR2F was developed. Tissues were homogenized in extraction buffer (1% Nonidet P40, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.4, and 20 μg/ml 4-(2-aminoethyl)-benzene sulfonyl fluoride) and clarified. Nunc MaxiSorp microtiter plates (Nalge Nunc International, Rochester, New York, USA) were coated overnight at 4°C with 1 μg/well of goat anti–human IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, Pennsylvania, USA). After washing and blocking with Tris-buffered saline (TBS) and casein (BioFX Laboratories Inc., Owings Mills, Maryland, USA), serum or tissue samples or purified SR2F standard (1–100 pg/well; R&D Systems Inc.) serially diluted in TBS/casein were added for a 1-hour incubation at room temperature. The detection antibody was 12.4 ng/well of biotinylated anti–TGF-β receptor type II (BAF241; R&D Systems Inc.). Color was developed using a 1:10,000 dilution of streptavidin-conjugated peroxidase (016-030-084; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) with peroxidase substrate (TMBW-0100-01; BioFX Laboratories Inc.).

Western blots and ligand affinity crosslinking.

For Western blots, mammary gland extracts (20 μg/lane) from wild-type or transgenic mice were run on 4–12% nonreducing Tris-glycine gels and blotted onto nitrocellulose. Purified SR2F (2 ng/well) was used as a positive control. Blots were probed with 0.2 μg/ml anti–human Fc antibody (109-005-098; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories), with or without an excess of human IgG (5 μg/ml) to demonstrate antibody specificity. For ligand affinity crosslinking, sera from 3-month-old virgin transgenic or wild-type mice were used, and purified SR2F (2 ng/0.1 ml) was spiked into wild-type serum or PBS as a positive control. 125I–TGF-β1 (131 μCi/μg) was added to a final concentration of 0.4 nM, and the reaction mixture was incubated on ice for 1 hour. Disuccinimidylsuberate (Pierce Chemical Co., Rockford, Illinois, USA) was added to a final concentration of 1 mM and incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature. Crosslinked samples were run on a 6% Tris-glycine gel under nonreducing conditions and exposed to film.

Tail vein metastasis assay.

The isogenic metastatic amelanotic melanoma cell line 37-32, derived from a melanoma arising in the HGF/SF transgenic mouse line MH-37, was cultured as previously described (27). Transgenic and age-matched wild-type male mice (aged 2–4 months) were injected intravenously with 106 cells in 0.1 ml of DMEM via the tail vein. In one experiment, mice were euthanized 21, 28, and 35 days after injection (5–10 mice/genotype group/timepoint). A second experiment looking at the dependence of metastatic efficiency on SR2F levels used 4–5 mice per genotype group, with all mice euthanized after 35 days. Mice were examined grossly at necropsy for the presence of metastases in internal organs. Microscopic quantitation of metastases was performed on representative cross sections of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue stained with hematoxylin and eosin, by a board-certified veterinary pathologist (M.R. Anver). For the liver, two sections of each liver lobe were examined.

Tumorigenesis in MMTV-neu mice.

Homozygous MMTV-neu mice [FVB/N-TgN(MMTV-neu)202Mul] were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine, USA) and crossed with FVB/NCr control mice or with homozygous MMTV-SR2F mice to generate two experimental cohorts, having either the neu oncogene alone (29 mice) or both neu and SR2F (38 mice). Female mice were cycled through one round of pregnancy and lactation to increase expression of the transgenes. Mice were palpated biweekly for mammary tumors and were euthanized when any primary tumor reached 2 cm in diameter or if the mouse appeared morbid. Tumor volume was calculated by the formula V = LS × 0.4 where L and S are the longest and shortest dimensions, respectively (28). Tumors, mammary glands, and lungs were collected for histological analysis, and serum was collected for assay of circulating SR2F levels.

Analysis of nonimmune phenotypes.

Complete necropsies were performed on 22 female FVB/NCr mice and 20 female SR2F+/+ mice 16–26 months of age, with a mean age of 20 ± 2 months for the FVB/NCr group and 21 ± 4 months for the SR2F group. Both virgin and parous mice were analyzed. At necropsy all mice were examined for the presence of gross lesions. Thirty-three organs were routinely harvested for histologic observation, as were any additional tissues with lesions. Hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue were examined by a board-certified veterinary pathologist (M.R. Anver). Serum and mammary glands were also collected for determination of SR2F levels by sandwich ELISA.

Immunophenotyping.

Whole blood was collected from transgenic and wild-type female mice by cardiac puncture, and complete blood cell counts and white blood cell differential were determined by Ani Lytics Inc. (Gaithersburg, Maryland, USA). To determine spleen cell counts, spleens were excised and ruptured, and erythrocytes were lysed with ACK lysing buffer (BioWhittaker Inc., Walkersville, Maryland, USA). Total spleen cells were counted using a hemocytometer, and were stained and analyzed by FACSCalibur using CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson and Co., San Jose, California, USA). For direct staining to determine total leukocyte distribution and to quantitate the activated and/or memory T cell phenotypes, the following conjugated antibodies were purchased from BD Pharmingen (San Diego, California, USA): anti-CD69 FITC, anti-CD25 phycoerythrin (PE), anti-CD62L FITC, anti-CD44 PE, anti-CD4 PerCP, allophycocyanin (APC), anti-CD8 PerCP, anti-CD3 APC, anti-B220 APC, anti-NK1.1 PE, anti-CD11b FITC, and anti–Ly-6G (Gr-1) PE. Before staining, Fc receptors were blocked with anti-CD16/32 antibody (2.4G2; BD Pharmingen).

Results

Validation of the SR2F antagonist in vitro.

The MDA MB435 human breast cancer cell line was stably transfected with SR2F, or with DNR as a positive control. The growth-inhibiting effect of TGF-β was largely eliminated in cells transfected with SR2F, and was completely abolished in cells transfected with DNR (Figure 1c). This shows that endogenously synthesized SR2F is capable of protecting the cells against the biological effects of added TGF-β. The lower efficiency of SR2F compared with DNR probably reflects the extensive dilution of the secreted SR2F in the culture medium. Using purified SR2F protein, we determined that a 50:1 molar ratio of SR2F to TGF-β1 is required for 90% neutralization of biological activity in vitro (Figure 1d). As has been shown previously, the SR2F could only bind TGF-β1 and TGF-β3, not TGF-β2 (ref. 20 and our data, not shown).

Characterization of MMTV-SR2F transgenic mice.

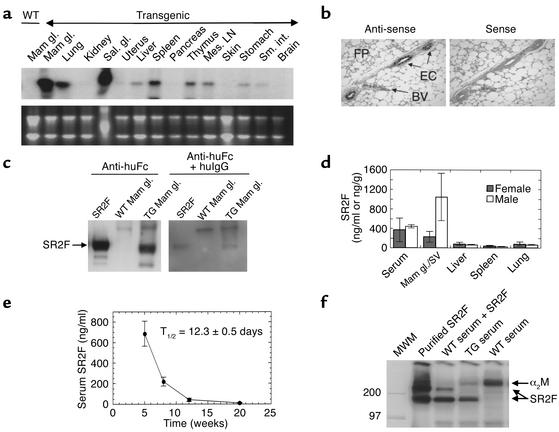

High-level expression of SR2F mRNA was observed in the mammary gland and salivary gland of homozygous transgenic females of the MMTV-SR2F line, with lower expression in the lung and lymphoid tissue (Figure 2a). In situ hybridization showed that SR2F mRNA expression in the mammary gland was restricted to the epithelial cells (Figure 2b). Extracts of transgenic mammary glands showed a band of the expected size for the dimeric SR2F on Western blots (Figure 2c). By ELISA, SR2F protein was found at the highest levels (200–1,000 ng/g) in the mammary glands and male accessory sex organs of adult mice, with lower but detectable levels (30–150 ng/g) in all other organs except the brain (Figure 2d and data not shown). The presence of SR2F in organs such as the kidneys, which show no SR2F mRNA expression, probably reflects sequestration from the circulation, since high levels of SR2F protein were also found in the serum (Figure 2d). Serum levels of SR2F were highest in very young mice, due to the additional presence of maternally transferred protein. By monitoring the decrease in circulating SR2F levels with time in the wild-type offspring of hemizygous transgenic mothers, we could calculate an in vivo half-life for the SR2F protein of 12.3 ± 0.5 days (Figure 2e). Note however that circulating SR2F levels in transgenic mice were generally maintained at ≥ 200 ng/ml throughout the life span of the animal, due to endogenous synthesis (not shown). The ability of SR2F made in vivo to bind to TGF-β was determined by ligand affinity crosslinking. 125I–TGF-β1 bound to an identical band in transgenic serum and in wild-type serum spiked with puri-fied SR2F (Figure 2f). In contrast, TGF-β bound only to a high-molecular-weight band corresponding to α2-macro-globulin in wild-type serum. This indicates that the SR2F made in vivo is correctly folded and is capable of binding TGF-β with higher affinity than can the major serum binding protein α2-macroglobulin, which is present in great excess.

Figure 2.

TGF-β antagonist expression and function in the MMTV-SR2F mouse. (a) Expression of SR2F mRNA in different tissues. RNA was prepared from an adult virgin female transgenic mouse and probed for SR2F. (b) Cell type–specific expression of SR2F in the mammary gland. In situ hybridization showed specific expression of SR2F mRNA in the mammary ductal epithelial cells (ECs) but not in the mammary fat pad (FP) or blood vessels (BVs) of a virgin transgenic mouse. (c) SR2F protein in the transgenic mammary gland. Western blots of mammary gland extracts from wild-type or transgenic (TG) mice were probed with anti–human Fc antibody (anti-huFc), with or without an excess of human immunoglobulin G1 (huIgG) to demonstrate specificity. Purified SR2F was the positive control. (d) SR2F protein levels in serum and tissues from transgenic mice. Sera and tissue extracts from 2.5-month-old virgin transgenic mice were assayed for SR2F protein. Results are the mean ± SD for three mice of each sex. (e) In vivo stability of SR2F. Serum levels of SR2F in the wild-type offspring of hemizygous transgenic dams were determined various times after birth. The serum half-life (T1/2) of SR2F was calculated from the decay curve. (f) Ability of SR2F in transgenic serum to bind TGF-β1. Serum from wild-type or transgenic mice was probed for TGF-β binding proteins by ligand affinity crosslinking with 125I–TGF-β1. Purified SR2F spiked into saline or wild-type serum were the positive controls. Mam gl., mammary gland; Sal. Gl., salivary gland; Mes. LN, mesenteric lymph node ; Sal. gl, salivary gland; Sm. int., small intestine; SV, Seminal vesicle; MWM, molecular weight markers; α2M, α2-macroglobulin.

The MMTV-SR2F mouse is protected against metastasis in a tail vein metastasis model system.

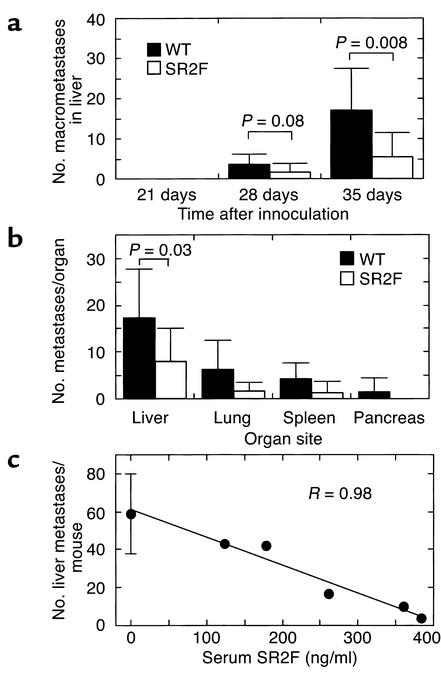

Several studies have implicated TGF-βs as prometastatic agents (29–31). To determine whether expression of SR2F would protect against experimental metastasis, age-matched cohorts of 3- to 4-month-old male MMTV-SR2F and wild-type FVB/NCr control mice were challenged by injection of the isogenic metastatic melanoma cell line 37-32 into the tail vein. A statistically significant decrease in the number of grossly detectable liver metastases was seen in MMTV-SR2F mice at both 28 and 35 days after injection of the cells (Figure 3a). On histological analysis, the MMTV-SR2F mice showed a two- to threefold decrease in the number of metastases per organ for all metastatic sites at 35 days (Figure 3b). For the liver, which was the most efficiently colonized site, the difference was statistically significant (P = 0.03 by Student t test for independent samples). In a separate experiment using 7-week-old mice, in which circulating SR2F levels varied quite widely among the transgenic cohort due to variable maternal transfer, there was a dose-dependent decrease in the number of liver metastases with increasing levels of circulating SR2F (Figure 3c).

Figure 3.

Effect of SR2F on metastatic efficiency in a tail-vein injection assay. (a) Macroscopically detectable liver metastases at different times after inoculation. Wild-type or transgenic (SR2F) mice were injected in the tail vein with 106 isogenic 37-32 melanoma cells. After 21, 28, and 35 days, mice were necropsied and the number of macroscopically visible metastases on the liver surface was quantified. The 21-day timepoint had five mice per genotype group, while the remaining timepoints had ten mice per genotype group. (b) Effects on metastatic efficiency in different internal organs. The number of histologically evident metastases was quantified in all tissues that showed evidence of gross metastases in mice necropsied at 35 days after inoculation. Two representative cross sections of each lobe were assessed for the liver and a single representative cross section was analyzed for other organs. Ten mice were used per genotype group. (c) Dose dependency of SR2F effect on metastatic efficiency. In a replicate experiment of the one described in a, the number of histologically detectable metastases in representative cross sections of the liver were quantitated and plotted against the circulating SR2F levels, as measured by sandwich ELISA on serum prepared at necropsy. The data for the wild-type cohort (0 ng/ml SR2F) are presented as mean ± SD (n = 4). R represents the correlation coefficient for the linear curve fit.

The SR2F antagonist protects against metastasis from a primary mammary tumor without affecting development of the primary tumor.

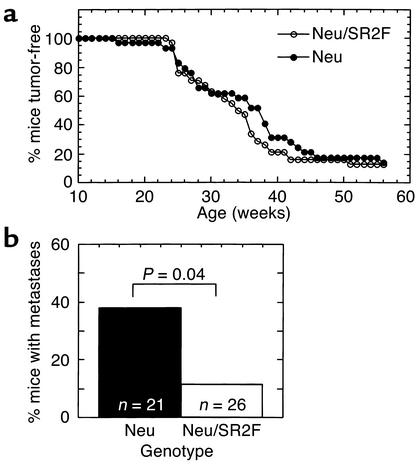

To determine whether the SR2F antagonist was effective in protecting against metastasis from a primary tumor arising in its natural site, we crossed MMTV-SR2F mice or control FVB/NCr mice with the MMTV-neu mouse model of metastatic breast cancer (32). In this model, mammary tumorigenesis is initiated by overexpression of the rat homologue of the HER2/erbB2/neu protooncogene. Since TGF-β is thought to act as a tumor suppressor in the early stages of tumorigenesis, we also wished to determine whether there were any adverse tumor-promoting effects following chronic exposure to the TGF-β antagonist during all stages of tumorigenesis. Mice were palpated for tumors weekly, and were necropsied when they appeared morbid or when any tumor reached 2 cm in diameter. At the time of necropsy, circulating SR2F levels in bigenic (neu/SR2F) mice were averaged 18.0 ± 10.2 μg/ml (range 4.3–38.8 μg/ml). This is significantly higher than is normally found in parous SR2F mice (∼1 μg/ml), and probably reflects additional production of SR2F by the tumor cells. In the 58-week time frame of the study, 25 of 29 (86.2%) mice in the neu group and 33 of 38 (86.8%) mice in the neu/SR2F group developed palpable mammary tumors. Tumor latency, as determined by the age at which a palpable tumor was first detected, was unaffected by the presence of SR2F (Figure 4a). Similarly, there was no effect of SR2F on tumor multiplicity or total tumor burden per mouse. neu mice had 2.4 ± 1.8 tumors per mouse, while neu/SR2F mice had 2.4 ± 1.7 tumors per mouse. The average total tumor burden for the neu mouse was 1.8 ± 1.0 cm3, while for the neu/SR2F mouse it was 1.7 ± 1.0 cm3. In contrast to the lack of effect on tumor latency, multiplicity, and size of the primary mammary tumors, the presence of SR2F significantly decreased the incidence of lung metastases in this model, by 3.3-fold (Figure 4b). This suggests that prolonged exposure to SR2F can protect the mouse against metastasis from an endogenous primary tumor without accelerating formation of the primary tumor.

Figure 4.

Effects of SR2F on primary tumorigenesis and metastasis in the MMTV-neu transgenic model of metastatic mammary cancer. MMTV-neu mice were crossed with FVB/NCr control mice or MMTV-SR2F mice to generate cohorts that either expressed neu alone (neu) or were bigenic for the neu and SR2F transgenes (neu/SR2F). Mice were cycled through one round of pregnancy and then monitored for development of tumors. (a) Tumor latency. Latency was determined as the time to first appearance of a palpable mammary tumor. The mean latency was 34 weeks for the neu group and 32.5 weeks for the bigenic neu/SR2F group (not statistically different). (b) Metastasis. Lungs from mice in both genotype groups were examined histologically for the presence of metastases.

Prolonged exposure to the SR2F TGF-β antagonist is not associated with major adverse side effects.

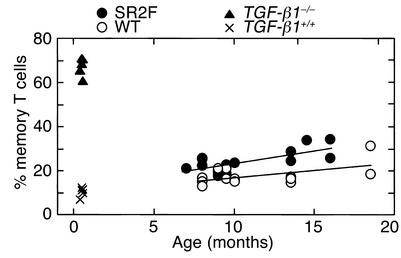

In genetically engineered mouse models, loss of TGF-β function is associated with profound immune system dysfunction and increased spontaneous tumorigenesis (17–19, 33, 34). To determine whether prolonged exposure to the SR2F TGF-β antagonist had similar effects, we analyzed MMTV-SR2F and wild-type FVB/NCr mice for immune phenotype and spontaneous pathology. At a very early age, the TGF-β1 null mouse develops a lymphoproliferative syndrome with autoimmune manifestations and myeloid hyperplasia (17, 18, 35, 36). However, in an analysis of 7- to 10-month-old MMTV-SR2F and FVB/NCr mice, we found no significant differences in numbers of circulating white blood cells, red blood cells, platelets, or segmented neutrophils (data not shown). No lymphadenopathy or splenomegaly were observed, and FACS analysis of spleen cells showed that the MMTV-SR2F mice had the normal proportion of B cells and of CD4 and CD8 single-positive T cells, suggesting there was no abnormal expansion of lymphocytes in the periphery. More detailed analysis of the splenic T cell population in larger cohorts of mice showed that the expression levels of early activation markers of T cells, such as CD69 and CD25, were the same in MMTV-SR2F mice and wild-type controls (data not shown). There was a small but significant increase in the fraction of CD4+ T cells with memory phenotype (CD4+CD44highCD62low; see Figure 5) and in CD8+ memory T cells (data not shown) in older MMTV-SR2F mice compared with age-matched controls. However, the increased acquisition of memory phenotype was minimal in comparison with that seen in the TGF-β1 null mice (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Effects of prolonged exposure to SR2F on memory T cell phenotype. The percentage of CD4+ T cells with a memory T cell phenotype (CD4+CD44highCD62Llow) was determined by FACS analysis of spleens from wild-type and MMTV-SR2F transgenic mice at different ages. TGF-β1 null (TGF-β1–/–) and age- and strain-matched wild-type (TGF-β1+/+) mice are shown for comparison. The TGF-β1 null mice do not survive beyond about 3 weeks of age.

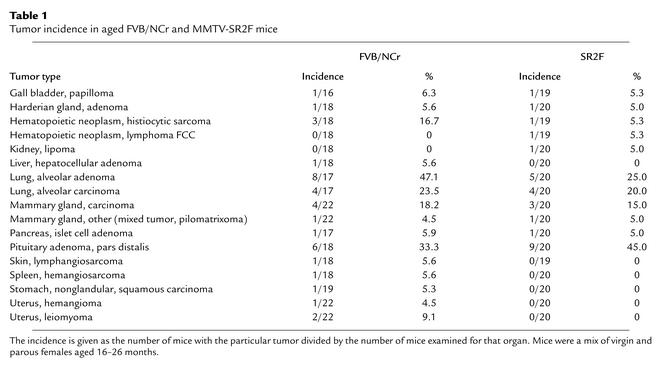

To determine whether there were other effects of prolonged exposure to SR2F, complete necropsies were performed on cohorts of 22 female FVB/NCr mice (mean age 20 ± 2 months) and 20 female MMTV-SR2F+/+ mice (mean age 21 ± 4 months). At the time of necropsy, SR2F levels in the transgenic group were averaged 930 ± 551 ng/ml (range 207–1,958 ng/ml) in the serum and 496 ± 287 ng/g (range 127–976 ng/g) in the mammary gland. The mean serum level of 930 ng/ml would be sufficient to neutralize 5 ng/ml TGF-β, which is more than saturating for most known biological responses. Thus the amount of SR2F in these aged mice was potentially more than adequate for neutralization of endogenous TGF-β. Despite these high levels of SR2F, there was no increase in the incidence of neoplastic lesions in any organs in the aged MMTV-SR2F mice compared with FVB/NCr controls (Table 1). The mean number of tumors per mouse was 1.5 ± 1.1 (n = 20) for SR2F mice and 1.6 ± 1.4 (n = 22) for FVB/NCr mice. In particular, colon tumors, which arise at high incidence in the TGF-β1 null mouse (19), were not found in either genotype group. Furthermore, there was no evidence for the diffuse vasculitis that is characteristic of the TGF-β1 null mouse (17, 18). The incidence of lymphocytic infiltration of the lung, kidney, and pancreas of the aged SR2F mice was increased compared with wild-type controls (data not shown). However, when present, the infiltrates were in the minimal to mild severity range, which is very different from the severe multifocal inflammatory response that limits the life span of TGF-β1 null mice. Similarly, the severe myocarditis that is a prominent feature of the TGF-β1 null mice (17) was not seen in the aged SR2F mice. Spontaneous murine cardiomyopathy is an age-related degenerative lesion of mice (37). The incidence of this condition, which is characterized by chronic inflammation and myofiber degeneration, was slightly increased in SR2F mice (95% of SR2F mice had the lesion, compared with 68% of FVB/NCr controls; P = 0.04). However, again the severity of these lesions, when present in either genotype, was only minimal to mild, and was not associated with any morbidity.

Table 1.

Tumor incidence in aged FVB/NCr and MMTV-SR2F mice

Discussion

Expression of TGF-βs, particularly TGF-β1, is increased in many human cancers and is correlated with enhanced invasion and metastasis (10). In breast cancer, TGF-β1 protein levels are increased at the advancing edge of primary human breast carcinomas and in lymph node metastases (38). Both the primary tumors and metastases appear to secrete TGF-β1 into the circulation, since newly diagnosed breast cancer patients were found to have elevated plasma TGF-β1 levels that were normalized by surgical resection in node-negative, but not node-positive, patients (39). Recent studies have shown that treatment with neutralizing TGF-β antibodies can suppress metastasis in mice inoculated with a variety of tumor cells, thereby confirming a causal role for TGF-β in the metastatic process (29–31). These observations make TGF-β an attractive molecular target for novel strategies for the prevention of metastasis. However, TGF-βs and their receptors are almost ubiquitously expressed in mammalian tissues (1). This poses a major conceptual problem with the long-term clinical use of TGF-β antagonists because of the likelihood of adverse side effects due to interference with the many important roles that TGF-βs play in normal tissues (1).

In the present study, we have shown that prolonged exposure to SR2F, a TGF-β antagonist of the soluble receptor:Fc fusion protein class, confers significant protection against metastasis arising either from an endogenous primary tumor or from injection of metastatic cells. Furthermore, we have shown that the antagonist does so without either enhancing the development of the primary tumor or inducing the life-threatening pathology that is seen in many mouse models in which TGF-β function is experimentally compromised by other mechanisms. For example, the TGF-β1 null mice have profound immune system defects and invariably develop a lethal multifocal inflammatory syndrome with many features of autoimmune disease (17, 18, 35). When crossed onto a Rag2 null background to prevent the lethal inflammation, TGF-β1 null mice develop colon carcinomas with high incidence (19). Similarly, experimentally diminished TGF-β signaling can promote tumorigenesis in many other epithelial tissues (24, 40, 41). However, in an extensive analysis of our aged MMTV-SR2F transgenic mice, we found that lifetime exposure to this form of TGF-β antagonist did not cause any increase in spontaneous tumorigenesis. Furthermore, the only immune phenotype observed in these mice was a small increase with age in the memory T cell population and a clinically insignificant increase in the incidence of minimal to mild lymphocytic infiltrates in the lung, pancreas, and kidney of 16- to 26-month-old animals.

Our data suggest that the SR2F TGF-β antagonist is capable of discriminating in vivo between the TGF-β that is associated with maintenance of normal homeostasis and the undesirable TGF-β that is involved in disease pathogenesis. We speculate that this discrimination may be either on the basis of TGF-β dose or accessibility. Late-stage metastatic disease, like many fibroproliferative disorders, is characterized by overexpression of TGF-βs (8, 10). For a given tissue, there may be a critical threshold dose of TGF-β above which undesirable genetic programs get activated. If this is so, the SR2F levels in our study may have been sufficient to reduce TGF-β to below the threshold level required for the promotion of metastasis while remaining above that needed for normal physiological function. Alternatively, the biological latency of TGF-β may be the feature that provides the therapeutic window of opportunity. Nearly all cells make TGF-β in a biologically latent form that must be activated before the ligand can bind to the receptor (42). Little is known about this process in vivo due to the difficulties in distinguishing latent and active TGF-β in situ. However, it has recently been shown that in the normal mammary gland, activation of latent TGF-β occurs very locally on a cell-by-cell basis, with active TGF-β restricted to the cell surface (43). Although the activation of TGF-β by tumors in situ has not yet been studied, it is known that highly metastatic cells in culture secrete a significant fraction of TGF-β in its active form, while normal cells secrete TGF-β almost exclusively in the latent form (44, 45). This raises the possibility that a relatively bulky antagonist like SR2F may have poor access to the cell-associated active TGF-β in normal tissues and early-stage tumors, but may be capable of effectively neutralizing the large amounts of more widely disseminated active TGF-β that are present in pathological states.

The biological mechanisms underlying the suppression of metastasis by SR2F in the models we have used are currently unclear. In the tail vein metastasis model, we believe the SR2F is affecting a step that is subsequent to extravasation. Studies in other model systems have shown that extravasation is not generally a limiting step, but rather that the formation of micrometastases from dormant single cells and the progression of micrometastases to macrometastases are the two most vulnerable steps (46). Our preliminary data suggest that the early formation of micrometastases by the melanoma cells in the liver of SR2F mice is at least as efficient as in the wild-type hosts, but that these small lesions fail to progress to form larger metastatic foci (data not shown). Indeed, metastases in the SR2F transgenic mice had a slightly lower proliferation rate than did those in wild-type mice (17.7% ± 5.2% bromodeoxyuridine-labeled cells vs. 23.7% ± 6.9%, respectively; P = 0.016), while apoptosis was essentially undetectable in metastases arising in mice of either genotype (data not shown). Since the 37-32 cells are growth-inhibited by TGF-β in vitro (data not shown), the in vivo proliferation data suggest that SR2F is acting indirectly to suppress metastasis. Plausible indirect mechanisms include enhanced immune surveillance and diminished angiogenesis (2, 47), and we are actively investigating these possibilities.

In summary, our data show that prolonged exposure to the SR2F TGF-β antagonist can significantly suppress metastasis in mice without any adverse side effects. Together with its high affinity and prolonged in vivo half-life, this unexpected selectivity makes the SR2F TGF-β antagonist an attractive candidate for clinical use. Most cancer patients die from their metastases, so chronic administration of SR2F to patients following diagnosis of a primary tumor might improve mortality by decreasing metastatic efficiency. Furthermore, this approach could be broadly applicable, since elevated TGF-β has been associated with poor prognosis in a wide variety of tumor types (10).

Acknowledgments

We thank Monica Tsang and Greg Fransen for the generous gift of the SR2F cDNA construct, Richard Simon for expert advice on the statistical analysis, and Lisa Birely for excellent technical assistance with the mice. This work was funded in part with Federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, NIH under contract no. NO1-CO-12400. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsements by the U.S. government.

Footnotes

See the related Commentary beginning on page 1533.

Yu-an Yang’s present address is: Department of Pathology, The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

References

- 1.Roberts, A.B., and Sporn, M.B. 1990. The transforming growth factors-β. In Handbook of experimental pharmacology. Peptide growth factors and their receptors. M.B. Sporn and A.B. Roberts, editors. Springer-Verlag. Berlin, Germany. 419–472.

- 2.Derynck R, Akhurst RJ, Balmain A. TGF-β signaling in tumor suppression and cancer progression. Nat Genet. 2001;29:117–129. doi: 10.1038/ng1001-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Massague J, Blain SW, Lo RS. TGFβ signaling in growth control, cancer, and heritable disorders. Cell. 2000;103:295–309. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00121-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Caestecker MP, Piek E, Roberts AB. Role of transforming growth factor-β signaling in cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1388–1402. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.17.1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reiss M. TGF-β and cancer. Microbes Infect. 1999;1:1327–1347. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(99)00251-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Topper JN. TGF-β in the cardiovascular system: molecular mechanisms of a context-specific growth factor. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2000;10:132–137. doi: 10.1016/s1050-1738(00)00061-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen W, Wahl SM. Manipulation of TGF-β to control autoimmune and chronic inflammatory diseases. Microbes Infect. 1999;1:1367–1380. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(99)00249-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Branton MH, Kopp JB. TGF-β and fibrosis. Microbes Infect. 1999;1:1349–1365. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(99)00250-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reed SG. TGF-β in infections and infectious diseases. Microbes Infect. 1999;1:1313–1325. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(99)00252-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gold LI. The role for transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) in human cancer. Crit Rev Oncog. 1999;10:303–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Border WA, et al. Natural inhibitor of transforming growth factor-β protects against scarring in experimental kidney disease. Nature. 1992;360:361–364. doi: 10.1038/360361a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Border WA, Okuda S, Languino LR, Sporn MB, Ruoslahti E. Suppression of experimental glomerulonephritis by antiserum against transforming growth factor β 1. Nature. 1990;346:371–374. doi: 10.1038/346371a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ueno H, et al. A soluble transforming growth factor β receptor expressed in muscle prevents liver fibrogenesis and dysfunction in rats. Hum Gene Ther. 2000;11:33–42. doi: 10.1089/10430340050016139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Isaka Y, et al. Gene therapy by transforming growth factor-β receptor-IgG Fc chimera suppressed extracellular matrix accumulation in experimental glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int. 1999;55:465–475. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zheng H, Wang J, Koteliansky VE, Gotwals PJ, Hauer-Jensen M. Recombinant soluble transforming growth factor β type II receptor ameliorates radiation enteropathy in mice. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1286–1296. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.19282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Q, et al. Reduction of bleomycin induced lung fibrosis by transforming growth factor β soluble receptor in hamsters. Thorax. 1999;54:805–812. doi: 10.1136/thx.54.9.805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kulkarni AB, et al. Transforming growth factor β 1 null mutation in mice causes excessive inflammatory response and early death. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:770–774. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.2.770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shull MM, et al. Targeted disruption of the mouse transforming growth factor-β 1 gene results in multifocal inflammatory disease. Nature. 1992;359:693–699. doi: 10.1038/359693a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Engle SJ, et al. Transforming growth factor β1 suppresses nonmetastatic colon cancer at an early stage of tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3379–3386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Komesli S, Vivien D, Dutartre P. Chimeric extracellular domain type II transforming growth factor (TGF)-β receptor fused to the Fc region of human immunoglobulin as a TGF-β antagonist. Eur J Biochem. 1998;254:505–513. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2540505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fernandez-Botran R. Soluble cytokine receptors: novel immunotherapeutic agents. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2000;9:497–514. doi: 10.1517/13543784.9.3.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang TC, et al. Mammary hyperplasia and carcinoma in MMTV-cyclin D1 transgenic mice. Nature. 1994;369:669–671. doi: 10.1038/369669a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hogan, B.L., Costantini, F., and Lacy, E. 1986. Manipulating the mouse embryo: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. Plainview, New York, USA. 53–57.

- 24.Bottinger EP, Jakubczak JL, Haines DC, Bagnall K, Wakefield LM. Transgenic mice overexpressing a dominant-negative mutant type II transforming growth factor β receptor show enhanced tumorigenesis in the mammary gland and lung in response to the carcinogen 7,12-dimethylbenz-[a]-anthracene. Cancer Res. 1997;57:5564–5570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Danielpour D, Dart LL, Flanders KC, Roberts AB, Sporn MB. Immunodetection and quantitation of the two forms of transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β 1 and TGF-β 2) secreted by cells in culture. J Cell Physiol. 1989;138:79–86. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041380112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jakowlew SB, Moody TW, You L, Mariano JM. Reduction in transforming growth factor-β type II receptor in mouse lung carcinogenesis. Mol Carcinog. 1998;22:46–56. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2744(199805)22:1<46::aid-mc6>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Otsuka T, et al. Disassociation of met-mediated biological responses in vivo: the natural hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor splice variant NK2 antagonizes growth but facilitates metastasis. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:2055–2065. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.6.2055-2065.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fueyo J, et al. Overexpression of E2F-1 in glioma triggers apoptosis and suppresses tumor growth in vitro and in vivo. Nat Med. 1998;4:685–690. doi: 10.1038/nm0698-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arteaga CL, et al. Anti-transforming growth factor (TGF)-β antibodies inhibit breast cancer cell tumorigenicity and increase mouse spleen natural killer cell activity. Implications for a possible role of tumor cell/host TGF-β interactions in human breast cancer progression. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:2569–2576. doi: 10.1172/JCI116871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wojtowicz-Praga S, et al. Modulation of B16 melanoma growth and metastasis by anti-transforming growth factor β antibody and interleukin-2. J Immunother Emphasis Tumor Immunol. 1996;19:169–175. doi: 10.1097/00002371-199605000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoefer M, Anderer FA. Anti-(transforming growth factor β) antibodies with predefined specificity inhibit metastasis of highly tumorigenic human xenotransplants in nu/nu mice. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1995;41:302–308. doi: 10.1007/BF01517218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guy CT, et al. Expression of the neu protooncogene in the mammary epithelium of transgenic mice induces metastatic disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:10578–10582. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.10578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gorelik L, Flavell RA. Abrogation of TGFβ signaling in T cells leads to spontaneous T cell differentiation and autoimmune disease. Immunity. 2000;12:171–181. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80170-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lucas PJ, Kim SJ, Melby SJ, Gress RE. Disruption of T cell homeostasis in mice expressing a T cell-specific dominant negative transforming growth factor β II receptor. J Exp Med. 2000;191:1187–1196. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.7.1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dang H, et al. SLE-like autoantibodies and Sjogren’s syndrome-like lymphoproliferation in TGF-β knockout mice. J Immunol. 1995;155:3205–3212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Letterio JJ, et al. Autoimmunity associated with TGF-β1-deficiency in mice is dependent on MHC class II antigen expression. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:2109–2119. doi: 10.1172/JCI119017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Price, P., and Papadimitriou, J.M. 1996. Genetic and immunologic determinants of age-related and virus-induced cardiopathy. In Pathobiology of the aging mouse. U. Mohr et al., editors. ILSI Press. Washington DC, USA. 373–383.

- 38.Dalal BI, Keown PA, Greenberg AH. Immunocytochemical localization of secreted transforming growth factor- β 1 to the advancing edges of primary tumors and to lymph node metastases of human mammary carcinoma. Am J Pathol. 1993;143:381–389. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kong FM, et al. Elevated plasma transforming growth factor-β 1 levels in breast cancer patients decrease after surgical removal of the tumor. Ann Surg. 1995;222:155–162. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199508000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tang B, et al. Transforming growth factor-β1 is a new form of tumor suppressor with true haploid insufficiency. Nat Med. 1998;4:802–807. doi: 10.1038/nm0798-802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Amendt C, Schirmacher P, Weber H, Blessing M. Expression of a dominant negative type II TGF-β receptor in mouse skin results in an increase in carcinoma incidence and an acceleration of carcinoma development. Oncogene. 1998;17:25–34. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Munger JS, et al. Latent transforming growth factor-β: structural features and mechanisms of activation. Kidney Int. 1997;51:1376–1382. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barcellos-Hoff MH, Ewan KBR. Transforming growth factor-β and breast cancer: mammary gland development. Breast Cancer Res. 2000;2:92–99. doi: 10.1186/bcr40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schwarz LC, et al. Aberrant TGF-β production and regulation in metastatic malignancy. Growth Factors. 1990;3:115–127. doi: 10.3109/08977199009108274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wakefield LM, Smith DM, Masui T, Harris CC, Sporn MB. Distribution and modulation of the cellular receptor for transforming growth factor-β. J Cell Biol. 1987;105:965–975. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.2.965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chambers AF, et al. Critical steps in hematogenous metastasis: an overview. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2000;10:243–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gorelik L, Flavell RA. Immune-mediated eradication of tumors through the blockade of transforming growth factor-β signaling in T cells. Nat Med. 2001;7:1118–1122. doi: 10.1038/nm1001-1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]