Abstract

Objective: Improving care for depressed primary care (PC) patients requires system-level interventions based on chronic illness management with collaboration among primary care providers (PCPs) and mental health providers (MHPs). We describe the development of an effective collaboration system for an ongoing multisite Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) study evaluating a multifaceted program to improve management of major depression in PC practices.

Method: Translating Initiatives for Depression into Effective Solutions (TIDES) is a research project that helps VA facilities adopt depression care improvements for PC patients with depression. A regional telephone-based depression care management program used Depression Case Managers (DCMs) supervised by MHPs to assist PCPs with patient management. The Collaborative Care Workgroup (CWG) was created to facilitate collaboration between PCPs, MHPs, and DCMs. The CWG used a 3-phase process: (1) identify barriers to better depression treatment, (2) identify target problems and solutions, and (3) institutionalize ongoing problem detection and solution through new policies and procedures.

Results: The CWG overcame barriers that exist between PCPs and MHPs, leading to high rates of the following: patients with depression being followed by PCPs (82%), referred PC patients with depression keeping their appointments with MHPs (88%), and PC patients with depression receiving antidepressants (76%). The CWG helped sites implement site-specific protocols for addressing patients with suicidal ideation.

Conclusion: By applying these steps in PC practices, collaboration between PCPs and MHPs has been improved and maintained. These steps offer a guide to improving collaborative care to manage depression or other chronic disorders within PC clinics.

The prevalence of depressive disorders is high among primary care (PC) patients, ranging between 5% and 10%,1 and is responsible for a heavy disability burden among affected patients.2,3 Rates of successful completion of appropriate treatment, however, are low.4,5 Research shows that collaboration between PC clinicians and mental health (MH) specialists is necessary if better outcomes are to be achieved.6–11 We describe the process used to institutionalize ongoing MH/PC collaboration across 7 Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) outpatient clinics in 5 states as part of a depression quality-improvement project, the Translating Initiatives for Depression into Effective Solutions (TIDES) project. TIDES is a researcher-clinical-management partnership project sponsored by the Quality Enhancement and Research Initiative (QUERI) of the VA. The purpose of TIDES is to encourage VA facilities to adopt depression care improvements using evidence-based quality improvement methods.12

METHOD

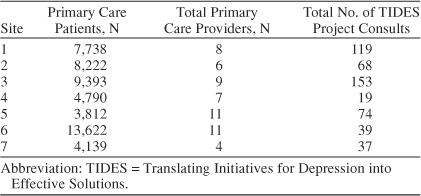

The TIDES team implemented the project in 3 VA regions, or Veterans Integrated Service Networks (VISNs). Each VISN identified 2 or 3 PC outpatient clinics (7 clinics in total) as demonstration sites for the TIDES depression care improvement initiative. Clinic sizes ranged from a caseload of 3812 patients to a caseload of 13,622 patients (Table 1). VISN directors and their MH and PC clinical leaders worked with researchers to identify depression care improvement priorities and evidence-based strategies for achieving these priorities. They then fit these strategies to VISN resources and preferences. Utilizing this process, these VISN leaders determined that collaboration between MH and PC was likely to be a central element of a successful depression care improvement initiative. They chose to implement regional telephone-based depression care management using registered nurses as Depression Care Managers (DCMs) who facilitate collaboration between PC and MH providers and assist PC providers with patient management. A MH lead clinician from each VISN supervised that VISN's DCM.

Table 1.

TIDES Utilization by Site

The project was organized around work groups dealing with specific aspects of the project. For example, an informatics work group developed software to facilitate collaborative care, and a Human Subjects work group dealt with human subjects issues. We therefore formed a multidisciplinary work group to support collaborative care (Collaborative Care Workgroup, or CWG). The CWG addressed barriers to collaboration as they were encountered. A psychiatrist with a consultation liaison background (B.L.F.) was the overall faculty leader of the group. The TIDES senior leaders provided the CWG with the following mission statement (see www.va.gov/tides_waves):

“This work group develops guidance, published on the TIDES List serve and on this website for managing depression through TIDES. This work group consists of mental health, primary care, and nursing opinion leaders from each TIDES clinics and from the VISN. An important goal of the TIDES/WAVES project is to improve collaboration between primary care and mental health providers. The Collaboration group works closely with each site learning how it operates. It then makes recommendations on how to best implement a site-specific collaborative care system between primary care providers, mental health providers and care managers. Another important goal of this Work Group is to develop ways to assure adequate supervision for the care managers.”

CWG participants included 1 or 2 nurses, 1 depression care manager, 3 or 4 MH specialists, and 1 to 3 PC clinicians from each VISN. In total there were 31 VISN participants and 7 research team participants, although on average there were 8 participants per meeting. The group planned to meet monthly. The group met 17 times by telephone conference call between June 2002 and March 2004, or a little less than once a month, and continues to meet. The CWG developed a 3-phase process to help sites implement a collaborative process for improving the quality of treatment for major depression in each of the PC clinics implementing collaborative care. The 3-phase process consists of identification of barriers to collaborative care, definition of specific target problems, and institutionalization of specific solutions.

Phase 1: Identify Barriers to Appropriate Management of Depression Within Primary Care

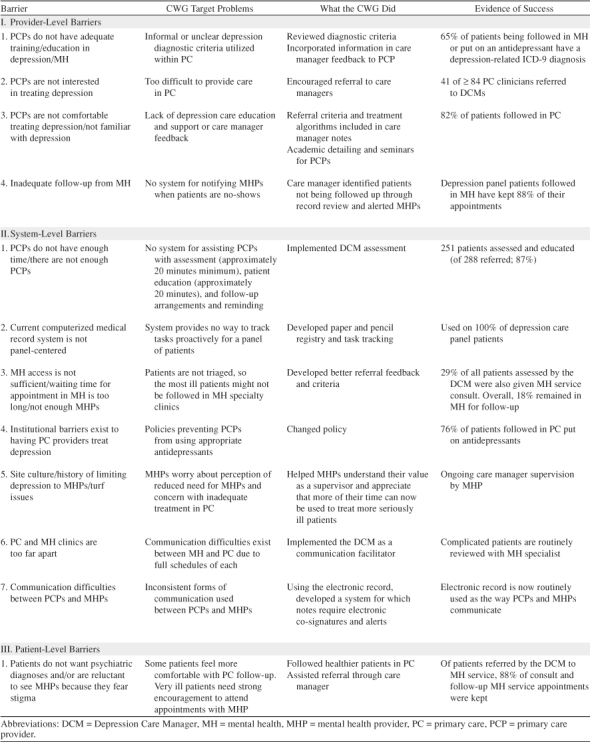

Prior to implementation of the depression care improvement initiative, we assessed existing barriers to MH-PC collaboration in the participating clinics. Two members of the TIDES research team conducted semi-structured telephone interviews with all the lead PC and lead MH clinical managers at each participating site.13 The interviews addressed (1) pre-intervention practices for screening, diagnosis, treatment, and management of depression care for depressed patients identified within PC, (2) perceived barriers to quality depression care, (3) the nature of pre-intervention collaboration between MH and PC services, and (4) perceived barriers to MH-PC collaboration. The TIDES interviewers recorded all interviews and conducted a content analysis of the verbatim transcripts. We used the results of the content analysis to generate a final list of barriers. The CWG classified these barriers as provider-, system-, and patient-level barriers (Table 2).

Table 2.

Site-Specific Depression Care Barriers Identified Through Qualitative Interviews and Collaborative Care Workgroup (CWG) Success in Overcoming Them

We also used the monthly teleconferences to receive ongoing information from DCMs and others about barriers to implementation that were being encountered at the sites. This method of information gathering allowed the CWG to respond to new concerns that arose after the initial interviews.

Phase 2: Identify Target Problems and Solutions

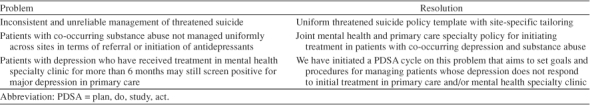

Often the barriers that the managers defined were too broad to lend themselves to remediation. Therefore, the second phase of the CWG focused on identifying clearly defined target problems related to these barriers and formulating specific solutions to those problems. Table 3 summarizes these problems and resolutions arrived at through the work of the CWG.

Table 3.

Problems Brought to the Collaborative Care Workgroup and Resolutions

Phase 3: Institutionalize Ongoing Problem Detection and Solution Through New Policies and Procedures

In addition to the important barriers identified by site leaders, the CWG identified several additional clinical and administrative concerns. The CWG provided a forum to discuss these and arrive at possible solutions.

Impact Assessment

To assess impact on patient care, we established registries of depressed patients referred for collaborative care in the 7 TIDES demonstration outpatient clinics. DCMs logged all patient contacts both in the electronic medical record and in an Excel-based (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, Wash.) data and task tracking system designed in partnership with the TIDES research team. They assessed depressive symptoms with the 9-item version of the Patient Health Questionnaire.14 Quarterly reports containing combined patient data were generated and analyzed locally, regionally, and nationally and were distributed to participating VISN clinical managers.

RESULTS

The 3-phase process resulted in identification of barriers to collaborative care and was used to develop and institutionalize effective solutions.

Phase 1: Identify Barriers to Appropriate Management of Depression Within Primary Care

Staff responses were considered by staff role: manager, leader, or clinician. Primary care and MH managers identified some of the same barriers; each group also identified some unique barriers. At least one participant from each specialty indicated that (1) PC providers lacked adequate time for treating depression (1 PC and 2 MH managers), (2) PC providers had inadequate MH training (1 PC and 3 MH leaders), and (3) there were problems with the computerized medical record (1 PC and 1 MH leader). One PC manager but no MH managers also identified each of the following barriers to managing depression within PC: (1) institutional policy as a barrier to having PC providers treat depression, (2) lack of interest in treating depression among PC clinicians, (3) turf issues between MH and PC, and (4) inadequate follow-up from MH. One MH manager, but no PC clinicians, identified each of the following barriers: (1) PC discomfort and lack of familiarity with treating depression, (2) insufficient MH specialty access, (3) distance between MH and PC clinics, and (4) patients not wanting to see a MH specialist. Utilizing this pre-intervention data, the CWG helped site members to clarify which barriers were present at their own sites and to take steps to implement site-specific solutions.

Phase 2: Identify Target Problems and Solutions

Columns 2 and 3 of Table 2 summarize the target problems and solutions. Column 4 of Table 2 reports preliminary evidence of success. For example, for the manager-identified provider-level barrier, “PCPs do not have adequate training,” the CWG identified the following corresponding target problem, “informal or unclear depression diagnostic criteria within PC.” To address this problem, the CWG incorporated diagnostic criteria into the care manager feedback to the PCP. Preliminary evidence indicates that this has been successful. Based on pre-intervention reports from site MH leaders, virtually no PC providers provided formal depression diagnoses when initiating treatment through a referral or prescribing an antidepressant. After initiation of the CWG solution, 65% of PC patients referred to MH clinics or put on treatment with an antidepressant by PC providers had a depression-related ICD-9 diagnosis.

We addressed system-level barriers in a similar manner. For example, site managers reported that PC providers do not have enough time or that there are not enough PC providers to treat depression. The CWG discovered that this time constraint might have been exacerbated by the lack of a system for assisting PC providers with patient assessment and education. To address this, the CWG implemented case manager assessment. Preliminary evidence indicates that this assessment has been successfully implemented; of 288 patients referred, 251 (87.2%) were assessed and educated about depression.

Site managers identified a primary patient-level barrier: patients do not want psychiatric diagnoses and/or are reluctant to see MH providers because they fear stigma. As with the provider- and system-level barriers, the CWG identified a specific corresponding target problem and solution. For those patients with mild to moderate depression who preferred to remain within PC, the DCM provided PC providers with assistance in managing these patients. For severely depressed patients, the DCM assisted PC providers with encouraging patients to accept referral to MH. Preliminary evidence indicates that DCMs have been highly successful in convincing patients to accept MH referrals; patients keep 87.7% of consult appointments and 87.6% of follow-up appointments that the DCM made.

Phase 3: Institutionalize Ongoing Problem Detection and Solution Through New Policies and Procedures

The CWG worked to develop policies that would make it easier for institutions to address barriers to care. One clinical and system concern that developed was how to care for patients with suicidal ideation. The CWG discovered that many sites lacked clear protocols on how to care for these patients. The CWG began by achieving a consensus on core components of a successful suicidal patient protocol. Sites began with these core components and adapted them to meet their unique site needs. The CWG proposed that each site adopt a chain-of-providers notification system; sites then determined who should be in this chain at their clinics. This is an example of a policy level solution that facilitates improved depression care.

The CWG also worked with sites to develop protocols for depressed patients with a comorbid substance abuse problem. Utilizing the same process as for suicidal patients, the CWG developed core components and worked with sites to develop site-specific protocols for these depressed patients who suffer from comorbid substance abuse disorders. Currently, the CWG is developing protocols to guide providers when their patients fail first-line treatments for depression. Additional information about this and the other protocols is available on the project Web site, www.va.gov/tides_waves. Using a forum like the CWG helps bring providers together to better identify and address specific concerns or problems requiring protocols to sustain efficient and effective collaboration.

DISCUSSION

Given the prevalence of depression within the PC population and the extent to which it is underdetected and undertreated, there is a compelling need to implement system changes to improve collaboration between PC and MH services. Programs that have implemented collaboration between these services have resulted in improved patient care.7–10 Effective collaborative systems between PC and MH services develop after health care organizations remove potential barriers to collaboration and make a concerted effort to institutionalize collaboration. We believe that health care organizations will be able to build effective collaborative programs by implementing similar steps and by focusing on the unique needs of their PC and MH clinics. Using a forum like the CWG helped bring providers together to better identify and address specific concerns or problems requiring protocols to sustain efficient and effective collaboration. These collaborative systems between PC and MH are currently functional across 7 distinct PC sites within the Veterans Administration health care system.

Many of the barriers and possible solutions described here should generalize beyond our sample. Clinicians at other institutions could therefore utilize the barriers list from Table 2 for identifying potential barriers within their own clinics. Some barriers will be specific to the VA. However, other barriers are common throughout PC and can be addressed regardless of setting. Ongoing discussion between PC and MH services will facilitate development of site-specific solutions to barriers.

Footnotes

Supported by Health Services Research and Development grants MNT 01-27 and IIR MHI-99-375 from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

The authors report no financial or other affiliation relevant to the subject of this article.

REFERENCES

- Katon W, Schulberg H. Epidemiology of depression in primary care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1992;14:237–247. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(92)90094-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays RD, Wells KB, and Sherbourne CD. et al. Functioning and well-being outcomes of patients with depression compared with chronic general medical illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995 52:11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ormel J, Von Korff M, and Ustun T. et al. Common mental disorders and disability across cultures: results from the WHO Collaboration Study on Psychological Problems in General Health Care. JAMA. 1994 272:1741–1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne JC, Schwenk TL, Fechner BS. Non-detection of depression by primary care physicians reconsidered. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1995;17:3–12. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(94)00056-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon GE, Von Korff M, and Wagner EH. et al. Patterns of antidepressant use in community practice. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1993 15:399–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon W, Von Korff M, and Lin E. et al. Collaborative management to achieve treatment guidelines: impact on depression in primary care. JAMA. 1995 273:1026–1031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon W, Robinson P, and Von Korff M. et al. A multifaceted intervention to improve treatment of depression in primary care. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996 53:924–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells K, Sherbourne C, and Schoenbaum M. et al. Impact of disseminating quality improvement programs for depression in managed primary care: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2000 283:212–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedrick SC, Chaney EF, and Felker B. et al. Effectiveness of collaborative care depression treatment in Veterans' Affairs primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2003 18:9–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubenstein LV, Chaney EF, Petzel R. Applying evidence from depression quality improvement research to VA. QUERI Quarterly. 2001;3:2–4. [Google Scholar]

- Felker B, Barnes R, and Greenberg D. et al. Preliminary outcomes from an integrated mental health primary care team. Psychiatr Serv. 2004 55:442–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubenstein LV, Mittman BS, and Yano EM. et al. From understanding health care provider behavior to improving health care: the QUERI framework for quality improvement. Quality Enhancement Research Initiative. Med Care. 2000 38(6 suppl 1):129–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fickel JJ, Parker LE, and Yano EM. et al. Improving depression care through primary care-mental health collaboration [poster]. Presented at the Academy Health Annual Research Meeting. 6–8June2004 San Diego, Calif. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of the self-report version of the PRIME-MD. JAMA. 1999;282:1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]