Abstract

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is an important syndrome among military veterans. Little has been written about comorbid medical conditions of PTSD, particularly overweight and obesity. We focus on psychotropic and non-psychotropic drugs, their interactions, and metabolic issues most relevant to primary care physicians.

Method: Data from the recently constituted PTSD program at the Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Richmond, Va., were retrospectively reviewed to assess the prevalence and severity of comorbid overweight and obesity in male veterans with PTSD. Also, our database allowed us to correlate various drugs used to treat hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and dyslipidemia with body mass index (BMI).

Results: The mean BMI of 157 veterans with PTSD (DSM-IV criteria) in this sample was in the obese range (30.3 ± 5.6 kg/m2). The number of drugs a given patient was taking for treatment of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and dyslipidemia correlated with BMI. Psychotropic drugs associated with weight gain did not explain our findings.

Conclusions: Overweight and obesity among our male veterans with PTSD strikingly exceeded national findings. The administration of psychotropic drugs associated with weight gain did not explain these findings. The number of medications used to treat hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and dyslipidemia correlated significantly with BMI. Rather than these medications explaining the high prevalence of overweight and obesity in our study population, obesity probably worsened these components of the metabolic syndrome, necessitating more aggressive treatment reflected in the high number of drugs prescribed.

The burden of obesity among military veterans was recently documented by Das et al.1 in a study population of 1,710,032 men and 93,290 women. These investigators found that among men, 73.0% were at least overweight, 32.9% were classified as obese, and 3.3% were found to be morbidly obese. Among women, 68.4% were at least overweight, 37.4% were classified as obese, and 6.0% were morbidly obese. Military veterans were not separated as to whether they did or did not have posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Military veterans with PTSD may receive a variety of psychotropic medications.2,3 Military veterans with psychiatric disorders are at increased risk for obesity and other features of the metabolic syndrome.4 Primary care physicians may find themselves challenged by the multiple medications prescribed to military veterans with PTSD plus metabolic disorders. The discovery of pervasive overweight and obesity as determined by body mass index (BMI) measurements among military veterans in our recently inaugurated PTSD program provided us the opportunity to assess BMI and its relationship with psychotropic medications and medications used to treat hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and dyslipidemia. Our observations form the body of this report.

METHOD

By late December 2004, the newly inaugurated Richmond, Va., PTSD program had enlisted over 200 veterans who were referred with clinical features of PTSD, subsequently met DSM-IV criteria for PTSD, and carried PTSD as their primary psychiatric diagnosis. Complete records were available for 170 veterans. Because nonblack, non-white veterans and female veterans constituted only a small fraction of our study population, we focused on 157 black and white male veterans. Variables assessed included (1) age, (2) race, (3) height, (4) weight, and (5) current medications. From the height and weight measurements, we calculated BMI (kg/m2).

The above data were collected as a part of a standard evaluation and were not part of any prospective research. The primary purpose of the database was to develop individualized clinical treatment. Thus, the data tabulation and analyses were not subject to Institutional Review Board review.

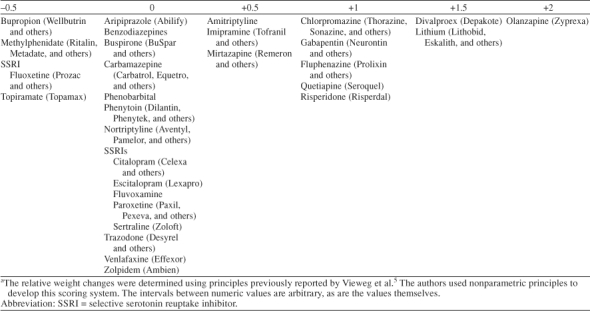

Table 1 lists psychotropic drugs and other central nervous system (CNS) drugs and their relative association with weight gain. This scoring system was derived from an earlier study,5 our clinical experience, an extensive review of the literature,6–31 and the recent consensus statement on antipsychotic drugs, obesity, and diabetes developed by the American Diabetes Association, American Psychiatric Association, American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, and North American Association for the Study of Obesity.32

Table 1.

Relative Weight Changes With Psychotropic Drugs and Other Central Nervous System Drugsa

Our scoring system employed nonparametric principles. There were 6 possible scores with a natural order (ordinal data). However, there were no clear-cut “units” separating each possible score.

RESULTS

Age and Race

The mean ± SD age of the 91 black male veterans was 55.8 ± 7.7 years, and the mean age of the 66 white male veterans was 57.2 ± 7.7 years. These age differences were not statistically significant (t = 1.155, df = 155, p = .250). We undertook no further analysis of age according to race.

BMI and Race

The mean BMI of the 91 black male veterans was 29.6 ± 5.9 kg/m2, and the mean BMI of the 66 white male veterans was 31.1 ± 5.1 kg/m2. These BMI differences did not reach a level of statistical significance (t = 1.609, df = 155, p = .110). We undertook no further analysis of BMI according to race.

BMI and Decade of Life

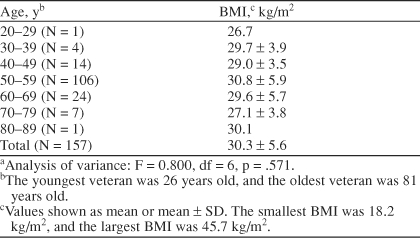

Differences in BMI by decade of life (Table 2a) did not reach statistical significance (p = .571). Most (67.5%) of our veterans were in the age range of 50 to 59 years, consistent with the fact that Vietnam veterans dominated our study population.

Table 2a.

Body Mass Index (BMI) by Decade of Life Among 157 Male Veterans With Posttraumatic Stress Disordera

BMI Groupings

BMI was in the normal range (< 25 kg/m2) for 24 veterans (15.3%). There were 60 veterans (38.2%) in the overweight range (≥ 25 kg/m2 to < 30 kg/m2), 63 veterans (40.1%) in the obese range (≥ 30 kg/m2 to < 40 kg/m2), and 10 veterans (6.4%) in the morbidly obese range (≥ 40 kg/m2) (Table 2b). That is, 84.7% of the black and white male veterans were overweight, obese, or morbidly obese.

Table 2b.

Body Mass Index (BMI) for 157 Male Veterans With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Categorized as Normal Weight, Overweight, Obese, and Morbidly Obesea

Medications

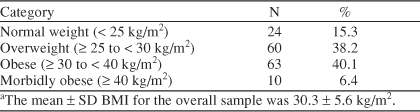

Psychotropic and other CNS drugs

Table 3 lists medications classified as psychotropic and other CNS drugs. Psychotropic agents were used to treat anxiety, depression, and psychosis-like symptoms. Other CNS drugs were used to treat seizures and pain. Some of these other CNS medications also had favorable effects on mood dys-regulation.

Table 3.

Psychotropic and Other Central Nervous System (CNS) Medications Taken by 157 Patients With PTSD and Number of Patients Who Received Each Drug

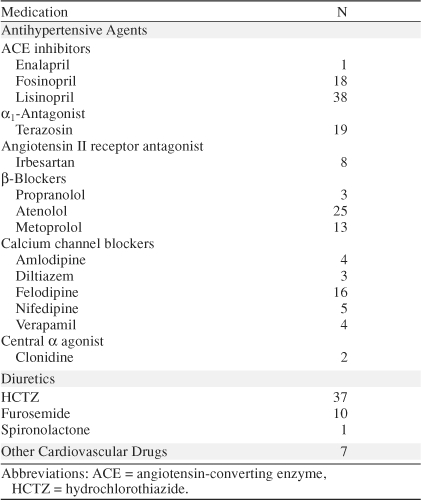

Antihypertensive drugs

Table 4 lists medications used to treat hypertension. We divided them broadly into antihypertensives and diuretics. We separated these medications from other cardiovascular drugs that included amiodarone, digoxin, and isosorbide mononitrate and isosorbide dinitrate.

Table 4.

Antihypertensive Drugs, Diuretics, and Other Cardiovascular Medications Taken by 157 Patients With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Number of Patients Who Received Each Drug

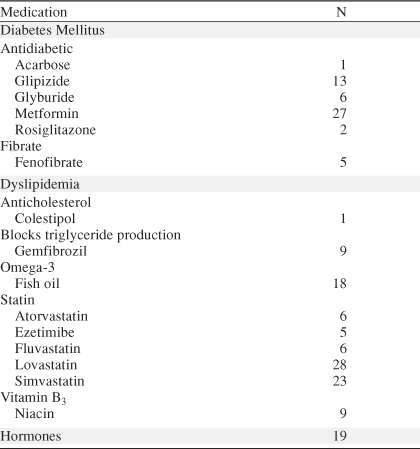

Drugs for diabetes mellitus and dyslipidemia

Table 5 lists medications used to treat diabetes mellitus and dyslipidemia. We created an additional category of hormones (insulin, levothyroxine, prednisone, and testosterone) but did not list those specific medications.

Table 5.

Medications for Diabetes Mellitus, Medications for Dyslipidemia, and Hormones Taken by 157 Patients With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Number of Patients Who Received Each Drug

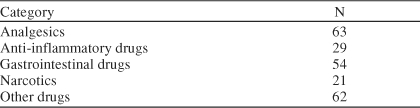

Other medications

Table 6 lists other drugs by general category. The Department of Veterans Affairs uses a national formulary so that the same medications are available to all facilities. We did not include topical drugs, antimicrobials, short-term treatments, aspirin, acetaminophen, aspirin/acetaminophen, non–narcotic-containing drugs, multivitamins, sildenafil, and electrolyte replacement.

Table 6.

Categories of Other Drug Medications Taken by 157 Patients With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Number of Patients Who Received Drugs From Each Category

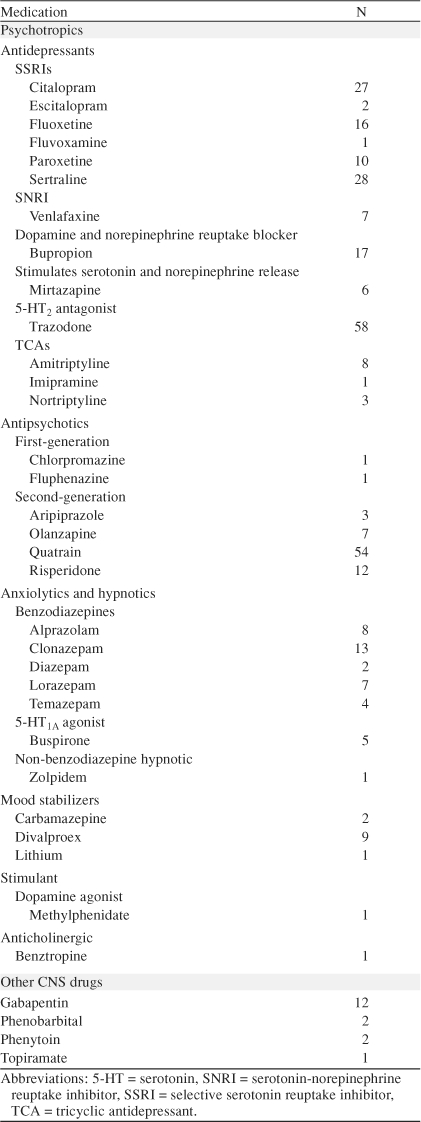

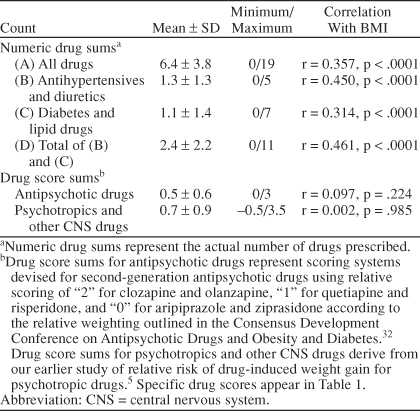

Medication Score and BMI

Table 7 lists drugs and drug scores correlated with BMI. The total number of drugs used to treat hypertension and those used to treat diabetes mellitus and dyslipidemia best correlated with BMI (r = 0.461, p < .0001). Neither second-generation antipsychotic drug scores nor psychotropic drug scores plus other CNS drug scores correlated with BMI. That is, psychotropic drug–induced weight gain did not seem to be a factor in the high prevalence of overweight and obesity among our study subjects.

Table 7.

Drugs and Number of Drugs Prescribed Correlated With Body Mass Index (BMI) for 157 Male Veterans With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

DISCUSSION

The mean BMI for the study population of male military veterans was 30.3 ± 5.6 kg/m2, and this did not vary by decade of life (Table 2). Thus, the typical patient was obese. Specifically, 38.2% of the veterans were overweight, 40.1% were obese, and 6.4% were morbidly obese. The most recent (1999–2000) National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) showed that among U.S. adults, the prevalence of overweight (34.0%) and obesity (30.5%) together reached a new high of 64.5%.33 Overweight among our veterans exceeded national figures by 4.2%, and obesity (obesity plus morbid obesity) exceeded national figures by 16.0%. Thus, combined overweight and obesity prevalence in our study sample exceed U.S. adult findings by 20%. Age, race, and decade of life appeared to have little effect on our findings even though the sixth decade of life is associated with the highest prevalence of obesity at a national level34 and veterans in this age group made up 67.5% of our study population (Table 2).

Morbid Obesity

The prevalence of morbid obesity in the United States is increasing much faster than that of nonmorbid obesity,35 and with morbid obesity come the most severe health consequences.36 Morbid obesity increased from 2.9% to 4.7% among U.S. adults from the 1988 through 1994 NHANES to the 1999 through 2000 NHANES.33 Of our 157 military veterans, 6.4% were morbidly obese (≥ 40 kg/m2). The greater the degree of obesity, the greater the number of excess deaths37 and years of life lost.38 Also, severely obese patients, especially younger women with a poor body image, are at high risk for depression.39 Finally, patients with morbid obesity are twice as likely as normal-weight adults to incur any health care expenditure.40

Our Observations Compared With the Literature

Arterburn et al.,41 in a quality-of-life survey, analyzed cross-sectional data that included BMI estimates among 15,857 veterans enrolled in the General Internal Medicine Clinics at 7 Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Centers, including the one in Richmond, Va. On the basis of the age distribution in that study,41 veterans were older than our study population, consistent with a larger proportion of World War II veterans. Arterburn et al.,41 using telephone-obtained height and weight data, found that 43.1% of their subjects were overweight and 28.4% were obese. The number of veterans overweight and obese in their study (71.5%) exceeded expected values (64.5%) based on current national surveys of the U.S. population.33 However, veterans in the study reported by Arterburn et al.41 did not reach the prevalence of overweight and obesity found in our study (84.7%) even though that study included veterans from the Richmond catchment area. The authors did not look at the prevalence of PTSD in their veteran population.41

David et al.42 assessed comorbid physical illnesses among veterans with PTSD and compared those findings with those of veterans with alcohol dependence. The authors reported a total of 74 medical conditions among their 55 PTSD veterans (mean age = 49.7 years). The mean ± SD BMI for their PTSD veterans42 was 30.1 ± 6.6 kg/m2 compared with our value of 30.3 ± 5.6 kg/m2. Compared with our obesity prevalence of 46.5%, 36% of their veterans were obese.

Recently, Das et al.1 reported that obesity was greatest (39.9%) in the age group 50 to 59 years among 1,710,032 military veterans. This figure divided into 34.6% for those obese and 5.3% for those morbidly obese. Among our military veterans in all age groups, 40.1% were obese (≥ 30 kg/m2 to < 40 kg/m2) and 6.4% were morbidly obese (≥ 40 kg/m2). Thus, our male military veterans with PTSD who were cared for by the Department of Veteran Affairs (DVA) tended to have more of a problem with obesity than the general population of male military veterans receiving care from DVA.

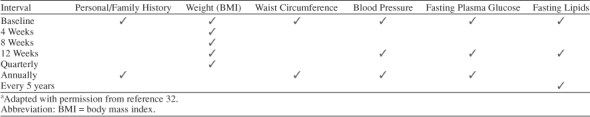

Antipsychotic Drugs and Weight Gain

Recently, emphasis has been placed on antipsychotic drug–associated weight gain—particularly weight gained during treatment with second-generation agents.32 Among the second-generation antipsychotic drugs, clozapine and olanzapine are most commonly associated with weight gain, risperidone and quetiapine are in the middle, and ziprasidone and aripiprazole are basically weight neutral.32 Among our study patients, administration of neither psychotropic drugs nor second-generation antipsychotic drugs contributed to the high prevalence of overweight and obesity. Table 8 outlines current parameters for psychiatrists to monitor when administering these agents.32 The same principles, of course, would apply to other clinicians prescribing these drugs. Despite the lack of an association between BMI and psychotropic drug administration in our study, given the strength of the evidence from the literature and the pervasiveness of overweight and obesity and their medical complications among our male PTSD veterans, these monitoring parameters seem to be the bare minimum when prescribing antipsychotic drugs for patients with PTSD.

Table 8.

Recommended Monitoring of Patients Receiving Second-Generation Antipsychotic Drugsa

CONCLUSIONS

Overweight and obesity among our male veterans with PTSD strikingly exceeded national findings. The administration of psychotropic drugs associated with weight gain did not explain these findings. The number of medications used to treat hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and dyslipidemia correlated significantly with BMI. Rather than these medications explaining the high prevalence of overweight and obesity in our study population, obesity probably worsened these components of the metabolic syndrome, necessitating more aggressive treatment reflected in the high number of drugs prescribed.

On the basis of our observations, treatment of PTSD among male military veterans should address comorbid medical conditions as well as the clinical features of PTSD. Additional studies are needed to better explain our findings.

Drug names: acarbose (Precose), alprazolam (Xanax, Niravam, and others), amiodarone (Cordarone, Pacerone, and others), amlodipine (Norvasc), aripiprazole (Abilify), atenolol (Tenormin and others), atorvastatin (Lipitor), benztropine (Cogentin and others), bupropion (Wellbutrin and others), buspirone (BuSpar and others), carbamazepine (Carbatrol, Equetro, and others), chlorpromazine (Thorazine, Sonazine, and others), citalopram (Celexa and others), clonazepam (Klonopin and others), clonidine (Duraclon, Catapres, and others), clozapine (Clozaril, FazaClo, and others), colestipol (Colestid), diazepam (Valium and others), digoxin (Lanoxicaps, Lanoxin, and others), diltiazem (Taztia, Cartia, and others), divalproex (Depakote), enalapril (Vasotec and others), escitalopram (Lexapro), ezetimibe (Zetia), felodipine (Plendil and others), fenofibrate (Antara, Tricor, and others), fluoxetine (Prozac and others), fluphenazine (Prolixin and others), fluvastatin (Lescol), fosinopril (Monopril and others), furosemide (Lasix and others), gabapentin (Neurontin and others), gemfibrozil (Lopid and others), glipizide (Glucotrol and others), glyburide (Diabeta, Micronase, and others), hydrochlorothiazide (Microzide, Oretic, and others), imipramine (Tofranil and others), irbesartan (Avapro), isosorbide dinitrate (Dilatrate, Isordil, and others), isosorbide mononitrate (Imdur, Ismo, and others), levothyroxine (Synthroid, Levo-T, and others), lisinopril (Zestril, Prinivil, and others), lithium (Lithobid, Eskalith, and others), lorazepam (Ativan and others), lovastatin (Altoprev, Mevacor, and others), metformin (Riomet, Fortamet, and others), methylphenidate (Ritalin, Metadate, and others), metoprolol (Toprol, Lopressor, and others), mirtazapine (Remeron and others), niacin (Niaspan, Niacor, and others), nortriptyline (Aventyl, Pamelor, and others), olanzapine (Zyprexa), paroxetine (Paxil, Pexeva, and others), phenytoin (Dilantin, Phenytek, and others), propranolol (Innopran, Inderal, and others), quetiapine (Seroquel), risperidone (Risperdal), rosiglitazone (Avandia), sertraline (Zoloft), sildenafil (Rivatio and Viagra), simvastatin (Zocor), spironolactone (Aldactone and others), temazepam (Restoril and others), terazosin (Hytrin and others), testosterone (Androderm, Testim, and others), topiramate (Topamax), trazodone (Desyrel and others), venlafaxine (Effexor), verapamil (Verelan, Isoptin, and others), ziprasidone (Geodon), zolpidem (Ambien).

Footnotes

Drs. Vieweg, Julius, Fernandez, Tassone, Narla, and Pandurangi report no financial or other relationship relevant to the subject of this article.

REFERENCES

- Das SR, Kinsinger LS, and Yancy WS. et al. Obesity prevalence among veterans at Veterans Affairs medical facilities. Am J Prev Med. 2005 28:291–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnurr PP, Friedman MJ, and Bernardy NC. Research on posttraumatic stress disorder: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and assessment. J Clin Psychol. 2002 58(pt 5). 877–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Acute Stress Disorder and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(suppl 11):1–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey DE. Metabolic issues and cardiovascular disease in patients with psychiatric disorders. Am J Med. 2005;118(suppl 2):15S–22S. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieweg WVR, Kuhnley LJ, and Kuhnley EJ. et al. Body mass index (BMI) in newly admitted child and adolescent psychiatric inpatients. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2005 29:511–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly DL, Conley RR, and Love RC. et al. Weight gain in adolescents treated with risperidone and conventional antipsychotics over six months. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 1998 8:151–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaemi SN, Katzow JJ. The use of quetiapine for treatment-resistant bipolar disorder: a case series. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 1999;11:137–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison DB, Mentore JL, and Heo M. et al. Antipsychotic-induced weight gain: a comprehensive research synthesis. Am J Psychiatry. 1999 156:1686–1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tohen M, Sanger TM, and McElroy SL. et al. Olanzapine versus placebo in the treatment of acute mania. Am J Psychiatry. 1999 156:702–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melkerrson KI, Hulting AL, Brismar KE. Elevated levels of insulin, leptin, and blood lipids in olanzapine-treated patients with schizophrenia or related psychoses. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61:742–749. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v61n1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tohen M, Jacobs TG, and Grundy SL. et al. Efficacy of olanzapine in acute bipolar mania: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000 57:841–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remschmidt H, Hennighausen K, and Clement H-W. et al. Atypical neuro-leptics in child and adolescent psychiatry. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000 9(suppl 1):I9–I19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin A, Landau J, and Leebens P. et al. Risperidone-associated weight gain in children and adolescents: a retrospective chart review. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2000 10:259–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haapasalo-Pesu K, Saarijarvi S. Olanzapine induces remarkable weight gain in adolescent patients. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;10:205–208. doi: 10.1007/s007870170028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanger TM, Grundy SL, and Gibson PJ. et al. Long-term olanzapine therapy in the treatment of bipolar I disorder: an open-label continuation phase study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001 62:273–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Glazewski R, and Khan S. et al. Weight gain with risperidone among patients with mental retardation: effect of caloric restriction. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001 62:114–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theisen FM, Linden A, and Geller F. et al. Prevalence of obesity in adolescent and young adult patients with and without schizophrenia and in relationship to antipsychotic medication. J Psychiatr Res. 2001 35:339–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellings JA, Zarcone JR, and Crandall K. et al. Weight gain in a controlled study of risperidone in children, adolescents, and adults with mental retardation and autism. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2001 11:229–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aman MG, De Smedt G, and Derivan A. et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled study of risperidone for the treatment of disruptive behaviors in children with subaverage intelligence. Am J Psychiatry. 2002 159:1337–1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werneke U, Taylor D, Sanders TAB. Options for pharmacological management of obesity in patients treated with atypical antipsychotics. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2002;17:145–160. doi: 10.1097/00004850-200207000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratzoni G, Gothelf D, and Brand-Gothelf A. et al. Weight gain associated with olanzapine and risperidone in adolescent patients: a comparative prospective study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002 41:337–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology Autism Network. Risperidone in children with autism and serious behavioral problems. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:314–321. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin A, L'Ecuyer S. Triglycerides, cholesterol and weight changes among risperidone treated youths: a retrospective study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;11:129–133. doi: 10.1007/s00787-002-0255-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavuluri MN, Janicak PG, Carbray J. Topiramate plus risperidone for controlling weight gain and symptoms in preschool mania. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2002;12:271–273. doi: 10.1089/104454602760386978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder R, Turgay A, and Aman M. et al. Effects of risperidone on conduct and disruptive behavior disorders in children with subaverage IQs. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002 41:1026–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gothelf D, Falk B, and Singer P. et al. Weight gain associated with increased food intake and low habitual activity levels in male adolescent schizophrenic inpatients treated with olanzapine. Am J Psychiatry. 2002 159:1055–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masi G, Cosenza A, and Mucci M. et al. A 3-year naturalistic study of 53 preschool children with pervasive developmental disorders treated with risperidone. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003 64:1039–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalsman G, Carmon E, and Martin A. et al. Effectiveness, safety, and tolerability of risperidone in adolescents with schizophrenia: an open-label study. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2003 13:319–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mozes T, Greenberg Y, and Spivak B. et al. Olanzapine treatment in chronic drug-resistant childhood-onset schizophrenia: an open-label study. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2003 13:311–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross RG, Novins D, and Farley GK. et al. A 1-year open-label trial of olanzapine in school-age children with schizophrenia. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2003 13:301–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyers SB. Medications as adjunct therapy for weight loss: approved and off-label agents in use. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105:948–959. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Diabetes Association, American Psychiatric Association, American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. et al. Consensus development conference on antipsychotic drugs and obesity and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004 27:596–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flegal KM, Carroll MD, and Ogden CL. et al. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2000. JAMA. 2002 288:1723–1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokdad AH, Ford ES, and Bowman BA. et al. Prevalence of obesity, diabetes, and obesity-related health risk factors, 2001. JAMA. 2003 289:76–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturm R. Increases in clinically severe obesity in the United States, 1986–2000. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2146–2148. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.18.2146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman DS, Khan LK, and Serdula MK. et al. Trends and correlates of class 3 obesity in the United States from 1990 through 2000. JAMA. 2002 288:1758–1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flegal KM, Graubard BI, and Williamson DF. et al. Excess deaths associated with underweight, overweight, and obesity. JAMA. 2005 293:1861–1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontaine KR, Redden DT, and Wang C. et al. Years of life lost due to obesity. JAMA. 2003 289:187–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon JB, Dixon ME, O'Brien PE. Depression in association with severe obesity: changes with weight loss. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2058–2065. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.17.2058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arterburn DE, Maciejewski ML, Tsevat J. Impact of morbid obesity on medical expenditures in adults. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2005;29:334–339. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arterburn DE, McDonell MB, and Hedrick SC. et al. Association of body weight with condition-specific quality of life in male veterans. Am J Med. 2004 117:738–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David D, Woodward C, and Esquenazi C. et al. Comparison of comorbid physical illnesses among veterans with PTSD and veterans with alcohol dependence. Psychiatr Serv. 2004 55:82–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]