Summary

cDNAs encoding functional T cell receptor (TCR) α and β chains from a CD4+ T cell line (SG6) generated by repeated stimulation of a melanoma patient's peripheral blood mononuclear cells with HLA-DP4–restricted, NY-ESO-1–specific peptide p161-180 were cloned using a 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA end method. Three different TCR α chains and 7 TCR β chains were found among the 84 α and 162 β cDNA clones tested. By screening different combination of the α/β chains using RNA electroporation, TRAV9-1 (Vα22.1) and TRBV20-1 (Vβ2) were found to be the functional pair in line SG6. Antibody blocking experiments confirmed that the specificity of TRAV9-1/TRBV20-1 mRNA-transfected T cells were CD4 dependent and HLA-DP4 restricted. A retroviral vector expressing both TRAV9-1 and TRBV20-1 was constructed and used for transduction of OKT3-stimulated peripheral blood lymphocytes from melanoma patients. TCR-transduced CD4 T cells were capable of recognizing peptide-pulsed antigen-presenting cells (Epstein-Barr virus transformed B-cells, dendritic cells, and peripheral blood mononuclear cells), and protein-pulsed dendritic cells. Transduced cells were also capable of proliferation upon peptide stimulation and recognized peptide concentrations that were recognized by the parental line (0.2 μM). In contrast to SG6, which could not recognize human tumors, TCR-transduced CD4 T cells could specifically recognize NY-ESO-1/HLA-DP4–expressing melanoma cells. Major histocompatibility complex class II TCR-transduced CD4 T cells provides an alternative source of tumor antigen-specific T cells for adoptive immunotherapy of cancer patients.

Keywords: NY-ESO-1, HLA-DP4, TCR, retroviral vector, gene transfer

The discovery of multiple cancer antigens (Ags) expressed on human tumors has provided a major stimulus to the development of human cancer immunotherapy.1 Human cancer Ags fall into several categories, including differentiation Ags that are expressed both on the tumor and on its normal counterpart, mutated proteins expressed exclusively on the cancer and not on normal tissues, and cancer-testes (CT) Ags.1,2 CT Ags are defined as proteins that have a restricted expression in adult tissue to testis and transformed cells. NY-ESO-1 is a member of the CT Ags3,4 and was identified by serological analysis of recombinant cDNA expression libraries analysis from a patient with esophageal cancer.5 It is a member of a multigene family located on the X chromosome (Xq28) that includes at least 2 additional members, LAGE-1 and ESO-3.6,7 NY-ESO-1 is an attractive tumor Ag for immunotherapy because it is expressed in a high percentage (20% to 80% at the RNA level) of common tumors, including cancers of the breast, lung, bladder, liver, prostate, and ovary, and a subset of these cancer patients develop Abs to NY-ESO-1.4 NY-ESO-1 expression and patient immune responses (mainly measured by Ab titer) can be correlated with the stage of malignancy.8-10

Most tumor Ags identified to date are nonmutated self-Ags, and for antitumor immune responses against such Ags to be generated, immunologic tolerance must be overcome. In contrast, the expression pattern of NY-ESO-1 is restricted to testicular germ cells and certain cancers, which may make it an easier target for tumor immunotherapy.3,11-13 Although adoptive immunotherapy can be effective in patients with melanoma, it has only rarely been attempted in other tumor types because of the difficulty of isolating highly tumor-reactive T cells in nonmelanoma patients. NY-ESO-1 encodes major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I-restricted and class II-restricted peptide epitopes that are expressed by a diverse range of cancers and recognized by T cells in vitro.8,14-17 Because NY-ESO-1 is expressed in about 30% of melanomas, as well as in a high percentage of common epithelial tumors and many types of sarcomas, it may be an ideal target for the development of adoptive immunotherapy for common cancers.

Several lines of evidence support the proposition that CD4+ T-helper (TH) cells are central to the development of an immune response against infection and malignancy by activating Ag-specific effector cells and recruiting cells of the innate immune system such as macrophages, eosinophils, and mast cells.18-24 In animal studies, antitumor immunity and autoimmunity mediated by gp75yTRP-1 seemed to require CD4+ T cells and Abs.25 Immunization of mice with hTRP-2, but not by mTRP-2, broke tolerance to the self-Ag and the antitumor immunity required for the participation of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells.26 The ability to break tolerance and enhance tumor regression was recently demonstrated to be specifically mediated by CD4+ TH cells.27 Together, these studies suggested that antitumor immunity could be mediated by either Abs or CD8+ T cells, but may require the critical help of CD4+ T cells.26,27

In previous clinical trials of adoptive immunotherapy using cloned melanoma-reactive CD8+ T cells, the transferred cells had high in vitro reactivity against melanoma Ags, yet objective clinical responses were not seen in these patients.28,29 More recent clinical trials conducted by our group demonstrated that autologous T-cell transfer after lymphodepleting chemotherapy could cause the regression of large vascularized tumors in patients with refractory metastatic melanoma. Eighteen of 35 patients treated with tumor-reactive lymphocyte cultures composed of both CD8+ and CD4+ T cells experienced an objective clinical response (>50% reduction in tumor), including 3 complete responders.30,31 We hypothesized that the lack of CD4+ helper cells within the transferred CD8+ cloned T cells may have limited the ability of these cells to mediate tumor regression in vivo.

In this report, cDNA encoding TCR α and β chains were cloned from an HLA-DP4–restricted, NY-ESO-1–specific CD4+ T cell line that was generated by repeated in vitro stimulation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) obtained from a melanoma patient previously vaccinated with the NY-ESO-1:161-180 peptide. Purified CD4+ T cells were retrovirally transduced with this TCR and these redirected CD4+ T cells gained the ability to recognize peptide-pulsed Ag-presenting cells (APCs), protein-pulsed dendritic cells, as well as tumor cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient PBMCs and Cell Lines

All of the PBMCs used in this study were from metastatic melanoma patients treated at the Surgery Branch, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD. T2 is a lymphoblastoid cell line deficient in TAP function, whose HLA class I proteins can be easily loaded with exogenous peptides.32 Melanoma lines, 1363mel(NY-ESO-1+, HLA-DP4+), 586mel(NY-ESO-1+, HLA-DP4+), 1359mel(NY-ESO-1+, HLA-DP4−), 624mel(NY-ESO-1+, HLA-DP4−), and 526mel(NY-ESO-1−, HLA-DP4−), were generated at the Surgery Branch from resected tumor lesions, as previous described.33,34 Cells obtained from other sources include: PG13 gibbon ape leukemia virus-packaging cell line (ATCC CRL 10,686), the human lymphoid cell line SupT1 (ATTC CRL-1942), and the human ecotropic packaging cell line, Phoenix Eco (kindly provided by G. Nolan, Stanford University, Stanford, CA). All the cell lines described above were maintained in R10 [RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen, Inc, Rockville, MD) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Biofluid, Inc, Gaithersburg, MD)]. Culture medium (CM) for T lymphocytes was RPMI 1640 with 0.05 mM mercaptoethanol, 300 IU/mL interleukin-2 (IL-2) (Chiron Corp, Emerville, CA), and 10% human AB serum (Valley Biomedical, Winchester, VA). The HLA-DP4–restricted, NY-ESO-1–specific CD4+ T cell line SG6 was generated by repeated in vitro stimulation, using the NY-ESO-1:161-180 peptide, of PBMCs obtained from a melanoma patient previously vaccinated with the same peptide.

Dendritic cells culture

Dendritic cells (DCs) were generated from PBMCs as described.35 Briefly, 3 mL of PBMCs were seeded in a 6-well plate at 5 × 106/mL in AIM-V for 2 hours; nonadherent cells were discarded and RPMI with 5% human AB serum in the presence of 1000 U/mL granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and IL-4 (PeproTech Inc) was added. After 6 to 7 days culture, the cells were collected and used without further maturation.

Peptide Synthesis

Synthetic peptides used in this study were made using a solid-phase method on a peptide synthesizer (Gilson Co Inc, Worthington, OH) at the Surgery Branch of the National Cancer Institute. The quality of each peptide was evaluated by mass spectrometry (Biosynthesis Inc, Lewisville, TX). The sequences of the peptide used in this study are as follows: NY-ESO-1 p157-168 (SLLMWITQCFLP), NY-ESO-1 p161-180 (WITQCFLPVFLAQPPSGQRA, an HLA-DP4 restricted epitope) gp100 209-217,36 Mart-1 27-35.37

Cloning of NY-ESO-1–specific, HLA-DP4–restricted TCR α and β cDNA

Total RNA was extracted with an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagene) from CD4 T cell line SG6 generated as described above. One microgram of total RNA was used to clone the TCR cDNAs by a rapid amplification of cDNA end (RACE) method (GeneRacer Kit, Invitrogen). Before synthesizing the single-strand cDNA, the RNA was dephosphorylated, decapped, and ligated with an RNA oligonucleotide according to the instruction manual of 5′ RACE GeneRacer Kit. SuperScript II RT and GeneRacer Oligo-dT were used for reverse transcribing the RNA Oligo-ligated mRNA to single-strand cDNAs. 5′ RACE was performed by using GeneRacer 5′ (GeneRacer Kit) as 5′ primer and gene-specific primer TCRCAR (5′-GTTAACTAGTTCAGCTGGACCACAGCCGCAGC-3′) or TCRCB1R (5′- CGGGTTAACTAGTTCAGAAATCCTTTCTCTTGACCATGGC -3′), or TCRCBR2 (5′-CTAGCCTCTGGAATCCTTTCTCTTG-3′) as 3′ primers for TCR α, β1, or β2 chains, respectively. The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) products were cloned into pCR2.1 TOPO vector (Invitrogen) and then transformed into One Shot TOP10 Competent Escherichia coli (Invitrogen). Plasmid DNAs were prepared from 96 individual clones from each construct for TCR α, β1, and β2 chains. Full-length insert of all the plasmids were sequenced to determine the vα/vβ usage.

Functional Screening of TCR α and β cDNA Combination by RNA Electroporation

Primary human T lymphocytes are refractory to most of nonviral DNA delivery methods and RNA electroporation was proved to be a very efficient way to deliver genes into primary T lymphocytes with both high transgene expression and viability of the transfected T cells.38 Combinations of the predominant clones for both α and β chains were tested for their functionality by in vitro-transcribed (IVT) RNA electroporation. The templates for generating IVT RNA were made by PCR using the primer T7-GR (5′-CTC TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGA CTGACTTGGACTGAAGGAGTAGAAA-3) as 5′ primer for both TCR α and β cDNA and 64T-CAR [5′-T(64) TCAGCTGGACCACAGCCGCAGC-3] for α cDNA, 64T-CB1R [5′-T(64) TCAGAAATCCTTTCTCTTGACCATGGC-3′] for β1, and 64T-CB2R [5′-T(64) CTAGCCTCTGGAATCCTTTCTCTTG-3] for β2 cDNA. PCR-produced templates were purified by using a PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen) before being used to generated IVT RNA. mMASSAGE mMACHINE High Yield Capped RNA Transcription Kit (Ambion Inc, Austin, TX) was used to generate IVT RNA. The IVT RNA was than purified using an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagene) and purified RNA was eluted in RNase-free water at 1 to 0.5 mg/mL. Human peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBLs) were stimulated with 50 ng/ mL OKT3 for 3 days and cultured in CM in the present of 300 IU/mL IL-2 until being electroporated. T cells subjected to electroporation were washed twice with OPTI-MEM (Invitrogen) and resuspended in OPTI-MEM at a final concentration of 25 × 106/mL. Subsequently, 0.05 to 0.2 mL of the cells were mixed with 2 μg/ 1 × 106 T cells of IVT RNA and electroporated in a 2-mm cuvette (Harvard Apparatus BTX, Holliston, MA), using ECM830 Electro Square Porator at 400 V and 500 μs (Harvard Apparatus BTX, Holliston, MA). Immediately after electroporation, the cells were transferred to fresh CM and incubated at 37°C for at least 2 hours before further use.

Construction of Retroviral Vectors and the Transduction of PBL

Retroviral vector backbone used in this study, pMSGV1, is a derivative of the vector pMSGV [murine stem cell virus (MSCV)-based splice-gag vector] which uses an MSCV long terminal repeat.39 AflIII or NcoI was introduced into the 5′ end of AV9-2 by PCR and the RNA generated from the PCR products were tested by coelectroporation of BV20-1 RNA to test whether the modifications affect the function of the gene. Retroviral vector pMSGV1-SG6-APB (SG6-APB), in which the expression of AV9-2 is driven by 5′long terminal repeat and BV20-1 is driven by PGK promoter, coexpressing both AV9-1 (with NcoI) and BV20-1 was constructed by ligation of 4 DNA fragments: pMSGV1 (NcoI/HindIII), PCR amplified AV9-2 (NcoI/XbaI), PGK promoter (XbaI/ClaI), and PCR amplified BV20-1 (ClaI/HindIII). The cloned inserts were determined by PCR, restriction enzyme digestion and DNA sequencing. The generation of PG13-packaging cell clones was conducted as previously described.36 MSGIN (GIN), whose name is derived from MSCV-based splice vector green fluorescent protein-internal ribosomal entry site-neo, was used as a control vector that expresses green fluorescent protein. PBLs were transduced with retroviral vectors by transfer to culture dishes that had been precoated with retroviral vectors as previously described.36

Flow Cytometry Analysis

Cell surface expression of Vβ2 and CD3 molecules on PBL was measured by flow cytometry using fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated or phycoerythrin-conjugated Abs, as directed by the supplier of anti-TCR Vβ2 (Immunotech, Westbrook, ME) and CD3 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). For analysis, the relative log fluorescence of live cells was measured using a FACScan flow cytometer (BD Biosciences).

Cytokine Release Assays

PBL cultures were tested for reactivity in cytokine release assays using commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits [interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and GM-CSF; Endogen, Cambridge, MA]. Cytokine release was measured with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-B or DCs pulsed with peptide (25 μg/mL, or as described in figure legends) in CM. Peptides were incubated with EBV-B or DCs for 4 hours at 37°C, before initiation of cocultures. For these assays, 1 × 105 responder cells (PBL) and 1 × 105 stimulator cells were incubated in a 0.2-mL culture volume in individual wells of 96-well plates. In experiments in which melanoma cells served as stimulator cells, 5 × 104 tumor cells were used in the same volume. Stimulator cells and responder cells were cocultured overnight. Cytokine secretion was measured in culture supernatants diluted as to be in the linear range of the assay.

RESULTS

Cloning and Testing Functional TCR α and β cDNAs

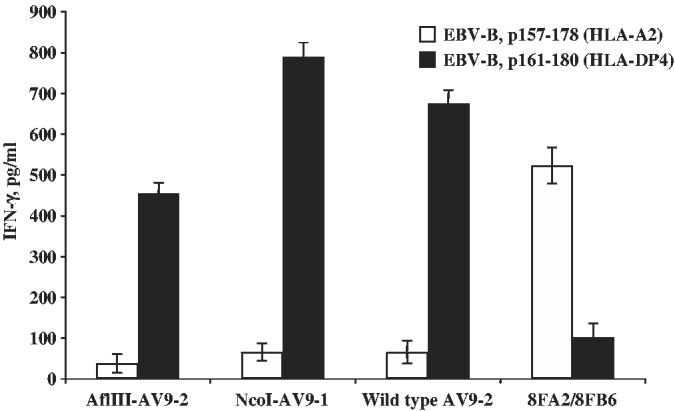

The CD4 T cell line SG6 was generated by repeated stimulation of PBMCs from a melanoma patient with NY-ESO-1–specific peptide p161-180, which was previously identified as an HLA-DP4–restricted epitope.16 Total RNA prepared from this T cell line was subjected to 5′ RACE and 96 cDNA clones from each PCR reaction for TCR α, β1, and β2 chain of TCR were sequenced. Vα/Vβ usage, together with the J region of the clones, is listed in Tables 1 and 2. Three Vα clones were obtained, with TRAV9-2-TRAJ15 (vα22.1) representing 89.4% of the cloned α chain genes. The Vβ usage was more heterogeneous (7 different sequences obtained) but VB20-1-TRBJ2-1 (vβ2) was the dominant clone (92.6%). As both TRAV9-1 and TRBA20-1 were dominantly presented at approximately the same ratio (around 90%) (Tables 1 and 2), it was likely that this pair of TCR came from the same T-cell clone. RNA electroporation was used to test the functionality of the cloned TCR α and β genes. To generate IVT RNA for the 3 Vα-chains and 3 Vβ-chains that were present at highest frequency (TRBV20-1, TRBV7-1, and TRBV19), PCR was conducted to produce DNA templates in which the T7 RNA polymerase promoter was introduced at the 5′ end of each cDNA. The functionality of the TCR pair TRAV9-2/TRBV20-1 and combinations of the other TCR α chains and β chains (as indicated in Fig. 1) were tested by coculturing TCR RNA electroporated CD4 T cells with peptide pulsed EBV-B cells.

TABLE 1.

TCR α Chain Sequencing Results

| TRAV | TRAJ | Clone No. | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| TRAV9-2 | TRAJ15 | 75 | 89.4 |

| TRAV13-1 | TRAJ43 | 6 | 7.1 |

| TRAV8-2 | TRAJ9 | 3 | 3.5 |

| Total | 84 | 100 |

Eighty-four plasmid clones for TCR α chain cloned from SG6 were sequenced. TRAV and TRAJ of each clone were determined.

TABLE 2.

TCR β Chain Sequencing Results

| TR BV | TRBJ | Clones | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| TRBV20-1 | TRBJ2-5 | 150 | 92.6 |

| TRBV7-2 | TRBJ1-2 | 5 | 3.1 |

| TRBV19 | TRBJ2-1 | 3 | 1.9 |

| TRBV12-3 | TRBJ2-1 | 1 | 0.6 |

| TRBV6-6 | TRBJ2-1 | 1 | 0.6 |

| TRBV12-1 | TRBJ1-1 | 1 | 0.6 |

| TRBV10-1 | TRBJ2-2 | 1 | 0.6 |

| Total | 162 | 100 |

162 plasmid clones for TCR β chain cloned from SG6 were sequenced. TRBV and TRBJ of each clone were determined.

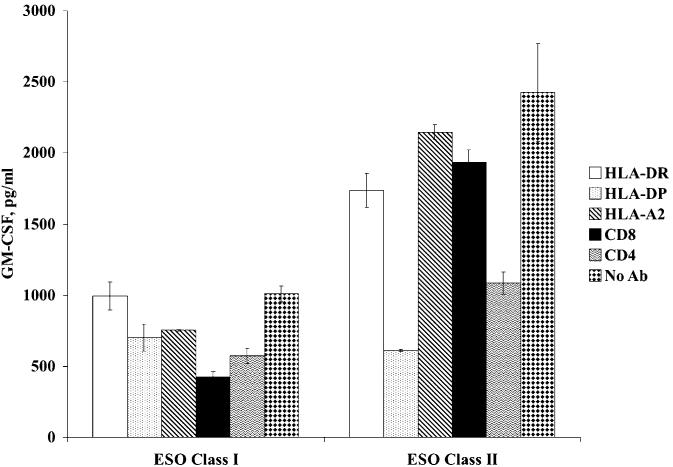

FIGURE 1.

Screening of TCR α/β pairs by RNA electroporation. OKT3-stimulated PBLs were electroporated with combinations of α/β as indicated and cocultured with peptide-pulsed EBV-B. IFN-γ secretion was measured by ELISA. SG6 CD4 T cell line and TCR α/β mRNA specific for NY-ESO-1 MHC class I (8FA2/8FB6, recognizing p157-168) were used as controls (SD were as shown, data are representative of 2 independent experiments).

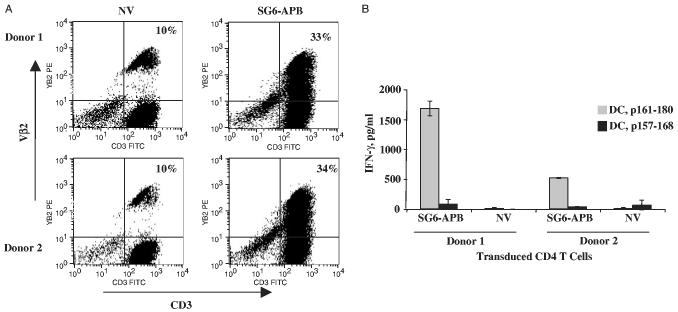

IVT RNAs coding for TCR α/β (8FA2/8FB6) that recognized the HLA-A2–restricted NY-ESO-1–specific epitope (NY-ESO-1 p157-168)39 was used as a control. As demonstrated in Figure 1, only the CD4 T cells electroporated RNA from TRAV9-1/TRBV20-1, but not the cells electroporated with combinations of RNAs from the 4 other α/β TCR cloned from SG6, specifically recognized NY-ESO-1 p161-180 peptide-pulsed EBV-B cells. The control TCR α/β pair 8FA2/8FB6 only recognized NY-ESO-1 p157-168 peptide-pulsed EBV-B cells, but not p161-180 peptide-pulsed EBV-B. To further confirm the specificity of the TCR pair TRAV9-1/TRBV20-1, a panel of antibodies (Abs) was used for Ab blocking. As shown in Figure 2, HLA-DP and CD4 Abs blocked the recognition of RNA-transfected CD4 T cells against NY-ESO-1p161-180 peptide-pulsed EBV-B (no blocking was observed with HLA-DR, HLA-A2, or CD8). On the basis of these data, the TCR pair TRAV9-1/TRBV20-1 was concluded to be the functional MHC class II-restricted anti–NY-ESO-1 TCR pair in CD4 T cell line SG6.

FIGURE 2.

Antibody blocking of Ag specificity of TCR electroporated CD4 T cells. OKT3-stimulated, CD4 T cells-purified PBLs were electroporated with α/β TCR mRNAs derived from TRAV9-2/TRBV20-1 (ESO class II), or 8FA2/8FB6 (ESO class I) as control, and cocultured with peptide-pulsed EBV-B in the presence of a panel of antibodies (as indicated). Twenty hours after coculture, GM-CSF secretion was measured by ELISA.

Transduction of CD4 T Cells With NY-ESO-1 Class II TCR

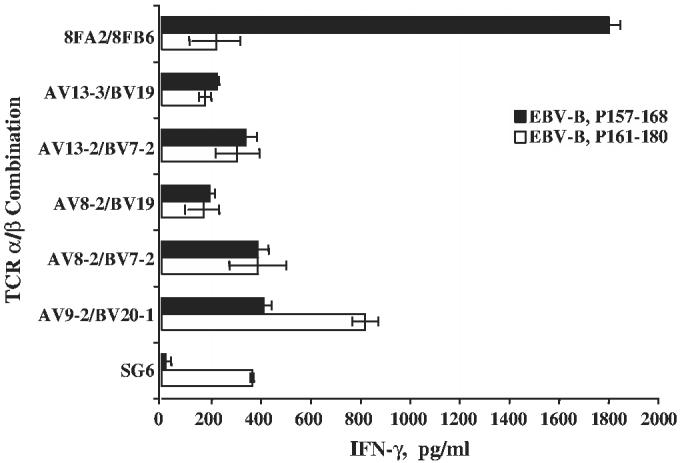

An NcoI compatible restriction enzyme site had to be introduced into the 5′ end of TRAV9-3 cDNA before insertion into the retroviral vector MSGV1. NcoI or AflIII together with the T7 promoter was introduced to the cDNA by PCR (changing the second amino acid from Asn to Asp or Try, respectively). RNAs were in vitro transcribed, coelectroporated with TRBV20-1 RNA into CD4 T cells and the function of the transfected T cells were tested by coculturing with peptide-pulsed EBV-B, using nonmodified TRAV9-1/TRBV20-1 and 8FA2/8FB6 RNA electroporated CD4 T cells as controls. The results showed that CD4 cells transfected with both the TRAV9-1 modified with NcoI or AflIII recognized peptide-pulsed EBV-B cells (Fig. 3). The modification with NcoI displayed better peptide recognition than the modification with AflIII. Therefore, TRAV9-1 with NcoI was used in the construction of vector SG6-APB (see Materials and Methods).

FIGURE 3.

Functional test of TRAV9-2 cDNA modified with different restriction enzyme sites. mRNAs for TRAV9-2 with (or without) second amino-acid substitutions (AflIII or NcoI) were coelectroporated with mRNA for TRBV20-1 into OKT3-stimulated CD4+ PBLs. IFN-γ secretion was measured by ELISA after coculture with peptide-pulsed EBV-B. mRNAs from 8FA2/8FB6 were used as control. The data are representative of 2 independent experiments.

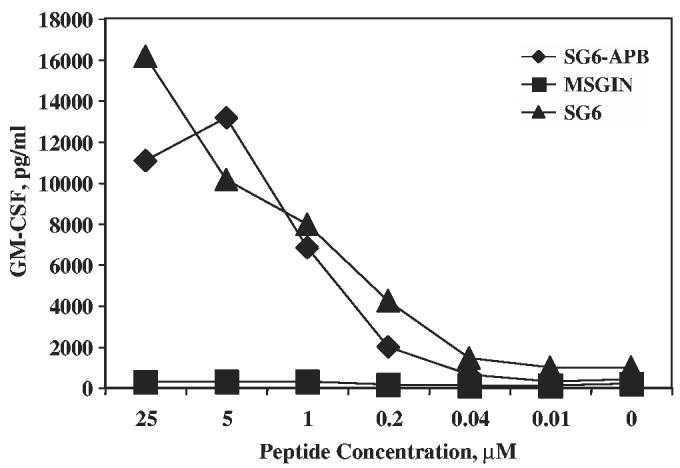

The transduction efficiency and the function of retroviral vector transduced CD4 T cells were tested using PBMCs from 2 donors. In all, 33% to 34% of Vβ2 expression could be detected in TCR vector transduced cells (Fig. 4A, background staining was 10%). Coculture of transduced CD4 T cells with peptide-pulsed autologous DCs demonstrated Ag-specific IFN-γ secretion by SG6-APB–transduced CD4 T cells from 2 donors, but not for nontransduced CD4 T cells (Fig. 4B). The transduced CD4 T cells also secreted GM-CSF and tumor necrosis factor-α upon coculturing with peptide-pulsed DCs (data not shown). When SG6-APB was transduced into purified CD8 T cells, there was no detectable cytokine secretion (data not shown), which confirms the results obtained from Ab blocking experiment (Fig. 3) that this TCR function is CD4 dependent. TCR affinity of transduced CD4 T cells was tested by coculturing the transduced T cells with serial dilution of peptide-pulsed DCs, compared with control vector MSGIN-transduced T cells and parental CD4 T-cell line SG6 (Fig. 5). A sensitivity of 40 to 200 nM was detected for both the parental SG6 line and SG6-APB–transduced CD4 T cells.

FIGURE 4.

Transduction of PBLs with TCR retroviral vector. OKT3-stimulated, CD8+-depleted PBLs from 2 melanoma patients were transduced with retroviral vector SG6-APB. A, Four days posttransduction, the transduced CD4 T cells that express Vβ2 and CD3 were detected by flow cytometry. B, SG6-APB–transduced cells were cocultured with peptide-pulsed DCs, nontransduced PBLs (NV) were used as control, IFN-g secretion was assayed by ELISA. These data are representative of 4 independent experiments.

FIGURE 5.

Peptide titration of specific recognition of SG6-APB–transduced PBLs. CD4+ PBLs were transduced with SG6-ABP or MSGIN retroviral vectors and cocultured with serial diluted NY-ESO-1 p161-180 peptide-pulsed DCs. SG6 CD4 T cell line was used as control. These data are representative of 3 independent experiments.

Recognition of Naturally Processed NY-ESO-1 Ag by TCR Transduced CD4 T Cell

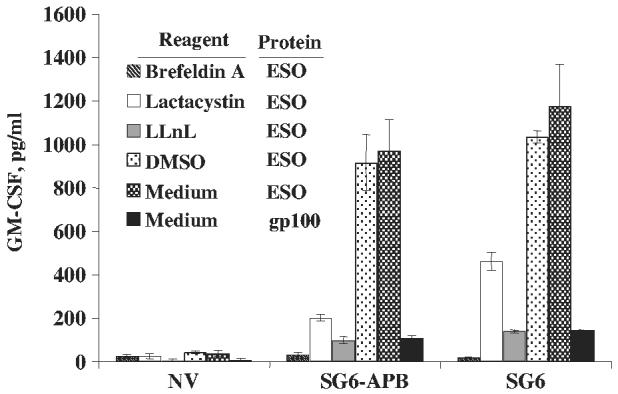

To test whether the transduced CD4 T cells could recognize naturally processed Ag presented by professional APC, NY-ESO-1 protein was loaded to immature autologous DCs. As a control, proteasome inhibitors were added to prevent protein processing. After overnight culture, the protein-pulsed DCs were cocultured with SG6-APB–transduced CD4 T cells for 24 hours, and cytokine secretion assayed by ELISA. Ag-specific cytokine secretion could be detected for both SG6-APB-transduced T cells and the parental line SG6 (Fig. 6). Identical results were obtained by the detection of IFN-γ secretion (data not shown). Specific recognition could be blocked by the addition of proteasome inhibitors, indicating that the recognition was mediated by the presentation of NY-ESO-1 peptide from the processed protein (not from the naturally degraded residual peptide left in the protein solution).

FIGURE 6.

Recognition protein-pulsed DCs by TCR-transduced T cells. SG6-APB–transduced CD4 T cells (SG6-APB) were exposed to NY-ESO-1 protein-pulsed DCs in the presence of protease inhibitors lactacystin (25 μM) and LLnL (50 μM), endocytic and cytosolic pathway inhibitor brefeldin A (1 μg/mL), dimethylsulfoxide or along with medium. GM-CSF secretion was assayed 20 hours after coculture. Nontransduced CD4 T cells (NV) and SG6 CD4 T cell line were used as control. These data are representatives of 3 independent experiments.

Proliferation of TCR-transduced CD4 T Cell

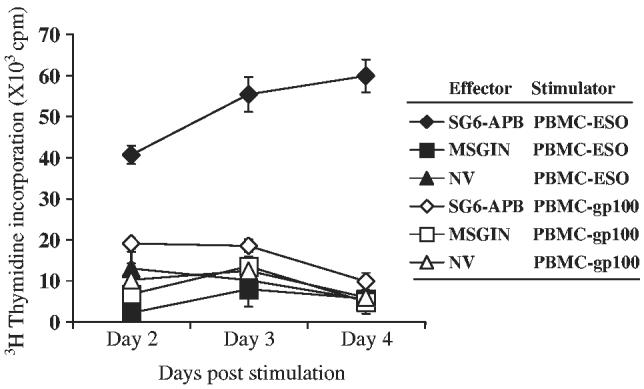

To test whether transduced T cells could proliferate upon being stimulated with peptide-pulsed APCs, SG6-APB-transduced CD4 T cells (MSGIN-transduced or nontransduced CD4 T cells were used as negative controls) were cocultured with NY-ESO-1 p161-180 peptide (gp100 peptide was used as control) pulsed HLA-DP4–positive PBMCs at T: PBMC ratio of 1:40. T-cell proliferation was detected by 3H-thymidine incorporation at days 2, 3, and 4 after coculture. As shown in Figure 7, proliferation could be seen only for the group of SG6-APB–transduced CD4 T cells stimulated with NY-ESO-1 peptide-pulsed PBMCs.

FIGURE 7.

Proliferation of SG6-APB–transduced CD4 PBLs. SG6-APB, MSGIN-transduced or nontransduced (NV) CD4 PBLs were cocultured with HLA-DP4+ PBMCs pulsed with NYESO-1 p161-180 (PBMC-ESO, filled symbols) or gp100 p209-217 (210M) (PBMC-gp100, open symbols) for 2, 3, or 4 days as indicated. 3H-thymidine incorporation was measured for the final 17 hours of culture. Data are representative of 3 experiments.

Tumor Recognition of TCR-transduced CD4 T Cell

For therapeutic purposes, it may be necessary for adoptively transferred T cells to recognize naturally presented Ag epitopes on tumor cells. We thus tested whether transduced CD4 T cells could recognize tumor cell lines that were positive for both NY-ESO-1 and HLA-DP4. Melanoma cell lines were cocultured with SG6-APB–transduced CD4 T cells (MSGIN-transduced or nontransduced CD4 T cells as controls) or parental line SG6. SG6-APB–transduced CD4 T cells recognized 586mel and 1363mel tumor lines that were positive for both NY-ESO-1and HLA-DP4, but not other melanoma lines, either HLA-DP4 negative (624mel) or NY-ESO-1 negative (526mel) or double negative (888mel) (Table 3). Like MSGIN-transduced or nontransduced CD4 T cells, the parental line SG6 did not recognize any melanoma lines tested, including the 2 melanoma lines (624mel and 1363mel) that were recognized by SG6-APB–transduced CD4 T cells.

TABLE 3.

Tumor Recognition of TCR-transduced CD4 T cells (IFN-γ, pg/mL)

| 624mel | 526mel | 888mel | 586mel | 1363mel | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSGIN | 131 (31) | 122 (31) | 182 (15) | 191 (32) | 167 (66) |

| SG6-APB | 163 (21) | 165 (26) | 190 (24) | 402 (29) | 393 (35) |

| NV | 146 (3) | 173 (23) | 197 (13) | 153 (12) | 208 (26) |

| SG6 | 137 (21) | 108 (51) | 125 (65) | 175 (75) | 117 (21) |

SG6-APB–transduced CD4 T cells (SG6-APB) were cocultured with melanoma cell lines 1363mel (NY-ESO-1+, HLA-DP4+), 586mel (NY-ESO-1+, HLA-DP4+), 1359mel (NY-ESO-1+, HLA-DP4−), 624mel (NY-ESO-1+, HLA-DP4−), and 526mel (NY-ESO-1−, HLA-DP4−). MSGIN-transduced, nontransduced (NV), and SG6 CD4 T cell lines were used as controls (SD is shown in parentheses). These data are representative of 5 independent experiments. Bold values are over 100 pg/ml and twice the negative control values.

DISCUSSION

Several lines of evidence suggest that Ag-specific T-helper cells are essential for the generation, maintenance, and therapeutic effectiveness of specific immune responses. The interaction between CD4 T cells and DCs via TCR and MHC class II provides both CD4 T cells and DCs with stimulation signals distinct from TCRMHC class I40-42 interactions. Ligation of MHC class II molecules induces a signaling cascade in human DCs and leads to the up-regulation of several cell surface molecules including both costimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86, which are actively involved in the Ag presentation process by APC, including T-cell activation and induction of maturation marker CD83.41 Recent data suggested that HLA-DR, HLA-DQ, and HLA-DP molecules transmit signals to monocytes via mitogen-activated protein kinases and lead to distinct monokine activation patterns, which may further affect T-cell response in vivo.43 It has also been reported that MHC class II may participate in the regulation of cytokine production by DC.44

TCR-transduced CD4 T cells in this study, unlike their parental line SG6 specifically recognized melanoma cell lines (Table 3). Direct killing of tumor or peptide-pulsed target cells was not observed in this study (data not shown). We found that TCR-transduced CD4 T cells lost the ability to recognize melanoma lines (data not shown) but still maintained the property of recognizing peptide after more than 6 weeks of culture in medium with 300 IU/mL IL-2. This may partially explain why the parental line SG6, that had been repeatedly stimulated and cultured in vitro for a long time period, could not recognize the tumors.

It is well established that the intensity or duration of T-cell responses is negatively modulated by CD4 T cells termed “suppressor cells”45 or T regulatory cells.46 These cells express the CD4+/CD25high phenotype, the Foxp3 transcription factor, and were proven to have a negative impact on tumor immunity.47-52 Engineering CD4+ T cells to become tumor Ag reactive raises a possibility of generating tumor-specific CD4+/CD25+ regulatory T cells. Because regulatory T cells are extremely difficult to expand under the conditions that are routinely used for T-cell transduction involving OKT3 stimulation and extended in vitro culture, it is unlikely that significant numbers of TCR-transduced CD4+/CD25high cells would be generated. Moreover, using the strategies of large-scale depletion of CD25+ regulatory T cells from patient leukopheresis samples53 also can prevent the genetic engineering of regulatory T cells.

MHC class I restricted, CD8-independent, CD4 T-cell–specific recognition by high-affinity TCR gene transfer has been reported.36,39,54 CD4 T cells transduced by such MHC class I-restricted TCR could recognize tumor-specific Ags in an HLA-A2–restricted, CD8-independent manner, may provide an alternative method to generate tumor Ag-specific T-helper cells, but there was no evidence that such CD4 T cells could exert helper function in vitro or in vivo. Whether high-affinity MHC class I-restricted, CD8-independent TCR-transduced CD4 T cells could fully function as their MHC class II-restricted counterpart, needs further investigation.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of the transfer of a native MHC class II-restricted TCR gene into human T cells, which has the potential to redirect T cells to gain the property of the parental CD4 T cell line. The MHC class I-restricted NY-ESO-1 TCR has been successfully cloned into retroviral vectors and PBLs redirected with this TCR by retroviral transduction were shown to be capable of recognizing and killing diverse human tumor cell lines.39 Simultaneous engineering of a population of T cells with both class I and class II-restricted TCR may provide a more powerful therapeutic effect on the adoptive immunotherapy of cancer patients with TCR-transduced T cells.

Footnotes

This work is supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rosenberg SA. Progress in human tumour immunology and immunotherapy. Nature. 2001;411:380–384. doi: 10.1038/35077246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenberg SA. A new era for cancer immunotherapy based on the genes that encode cancer antigens. Immunity. 1999;10:281–287. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80028-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scanlan MJ, Gure AO, Jungbluth AA, et al. Cancer/testis antigens: an expanding family of targets for cancer immunotherapy. Immunol Rev. 2002;188:22–32. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2002.18803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scanlan MJ, Simpson AJ, Old LJ. The cancer/testis genes: review, standardization, and commentary. Cancer Immun. 2004;4:1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen YT, Scanlan MJ, Sahin U, et al. A testicular antigen aberrantly expressed in human cancers detected by autologous antibody screening. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:1914–1918. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.5.1914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lethe B, Lucas S, Michaux L, et al. LAGE-1, a new gene with tumor specificity. Int J Cancer. 1998;76:903–908. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19980610)76:6<903::aid-ijc22>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alpen B, Gure AO, Scanlan MJ, et al. A new member of the NY-ESO-1 gene family is ubiquitously expressed in somatic tissues and evolutionarily conserved. Gene. 2002;297:141–149. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(02)00879-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gnjatic S, Atanackovic D, Jager E, et al. Survey of naturally occurring CD4+ T cell responses against NY-ESO-1 in cancer patients: correlation with antibody responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:8862–8867. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1133324100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jager E, Nagata Y, Gnjatic S, et al. Monitoring CD8 T cell responses to NY-ESO-1: correlation of humoral and cellular immune responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:4760–4765. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.9.4760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jager E, Stockert E, Zidianakis Z, et al. Humoral immune responses of cancer patients against “cancer-testis” antigen NY-ESO-1: correlation with clinical events. Int J Cancer. 1999;84:506–510. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19991022)84:5<506::aid-ijc10>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jager E, Gnjatic S, Nagata Y, et al. Induction of primary NY-ESO-1 immunity: CD8+ T lymphocyte and antibody responses in peptide-vaccinated patients with NY-ESO-1+ cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:12198–12203. doi: 10.1073/pnas.220413497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gnjatic S, Jager E, Chen W, et al. CD8(+) T cell responses against a dominant cryptic HLA-A2 epitope after NY-ESO-1 peptide immunization of cancer patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:11813–11818. doi: 10.1073/pnas.142417699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khong HT, Yang JC, Topalian SL, et al. Immunization of HLA-A*0201 and/or HLA-DPbeta1*04 patients with metastatic melanoma using epitopes from the NY-ESO-1 antigen. J Immunother. 2004;27:472–477. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200411000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jager E, Chen YT, Drijfhout JW, et al. Simultaneous humoral and cellular immune response against cancer-testis antigen NY-ESO-1: definition of human histocompatibility leukocyte antigen (HLA)-A2-binding peptide epitopes. J Exp Med. 1998;187:265–270. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.2.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zeng G, Touloukian CE, Wang X, et al. Identification of CD4+ T cell epitopes from NY-ESO-1 presented by HLA-DR molecules. J Immunol. 2000;165:1153–1159. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.2.1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zeng G, Wang X, Robbins PF, et al. CD4(+) T cell recognition of MHC class II-restricted epitopes from NY-ESO-1 presented by a prevalent HLA DP4 allele: association with NY-ESO-1 antibody production. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:3964–3969. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061507398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zarour HM, Maillere B, Brusic V, et al. NY-ESO-1 119-143 is a promiscuous major histocompatibility complex class II T-helper epitope recognized by Th1- and Th2-type tumor-reactive CD4+ T cells. Cancer Res. 2002;62:213–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Surman DR, Dudley ME, Overwijk WW, et al. Cutting edge: CD4+ T cell control of CD8+ T cell reactivity to a model tumor antigen. J Immunol. 2000;164:562–565. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.2.562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cohen PA, Peng L, Plautz GE, et al. CD4+ T cells in adoptive immunotherapy and the indirect mechanism of tumor rejection. Crit Rev Immunol. 2000;20:17–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kalams SA, Walker BD. The critical need for CD4 help in maintaining effective cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses. J Exp Med. 1998;188:2199–2204. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.12.2199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ossendorp F, Toes RE, Offringa R, et al. Importance of CD4(+) T helper cell responses in tumor immunity. Immunol Lett. 2000;74:75–79. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(00)00252-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nishimura T, Iwakabe K, Sekimoto M, et al. Distinct role of antigen-specific T helper type 1 (Th1) and Th2 cells in tumor eradication in vivo. J Exp Med. 1999;190:617–627. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.5.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hung K, Hayashi R, Lafond-Walker A, et al. The central role of CD4(+) T cells in the antitumor immune response. J Exp Med. 1998;188:2357–2368. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.12.2357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fallarino F, Grohmann U, Bianchi R, et al. Th1 and Th2 cell clones to a poorly immunogenic tumor antigen initiate CD8+ T cell-dependent tumor eradication in vivo. J Immunol. 2000;165:5495–5501. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.10.5495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Overwijk WW, Lee DS, Surman DR, et al. Vaccination with a recombinant vaccinia virus encoding a “self” antigen induces autoimmune vitiligo and tumor cell destruction in mice: requirement for CD4(+) T lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:2982–2987. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.2982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bowne WB, Srinivasan R, Wolchok JD, et al. Coupling and uncoupling of tumor immunity and autoimmunity. J Exp Med. 1999;190:1717–1722. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.11.1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Antony PA, Piccirillo CA, Akpinarli A, et al. CD8+ T cell immunity against a tumor/self-antigen is augmented by CD4+ T helper cells and hindered by naturally occurring T regulatory cells. J Immunol. 2005;174:2591–2601. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.5.2591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dudley ME, Wunderlich J, Nishimura MI, et al. Adoptive transfer of cloned melanoma-reactive T lymphocytes for the treatment of patients with metastatic melanoma. J Immunother. 2001;24:363–373. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200107000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Yang JC, et al. A phase I study of nonmyeloablative chemotherapy and adoptive transfer of autologous tumor antigen-specific T lymphocytes in patients with metastatic melanoma. J Immunother. 2002;25:243–251. doi: 10.1097/01.CJI.0000016820.36510.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosenberg SA, Dudley ME. Cancer regression in patients with metastatic melanoma after the transfer of autologous antitumor lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(Suppl 2):14639–14645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405730101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Yang JC, et al. Adoptive cell transfer therapy following non-myeloablative but lymphodepleting chemotherapy for the treatment of patients with refractory metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2346–2357. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.00.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salter RD, Howell DN, Cresswell P. Genes regulating HLA class I antigen expression in T-B lymphoblast hybrids. Immunogenetics. 1985;21:235–246. doi: 10.1007/BF00375376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Topalian SL, Solomon D, Rosenberg SA. Tumor-specific cytolysis by lymphocytes infiltrating human melanomas. J Immunol. 1989;142:3714–3725. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zeng G, Li Y, El-Gamil M, et al. Generation of NY-ESO-1-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells by a single peptide with dual MHC class I and class II specificities: a new strategy for vaccine design. Cancer Res. 2002;62:3630–3635. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Romani N, Gruner S, Brang D, et al. Proliferating dendritic cell progenitors in human blood. J Exp Med. 1994;180:83–93. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morgan RA, Dudley ME, Yu YY, et al. High efficiency TCR gene transfer into primary human lymphocytes affords avid recognition of melanoma tumor antigen glycoprotein 100 and does not alter the recognition of autologous melanoma antigens. J Immunol. 2003;171:3287–3295. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.6.3287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hughes MS, Yu YY, Dudley ME, et al. Transfer of a TCR gene derived from a patient with a marked antitumor response conveys highly active T-cell effector functions. Hum Gene Ther. 2005;16:457–472. doi: 10.1089/hum.2005.16.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhao Y, Zheng Z, Cohen CJ, et al. High-efficiency transfection of primary human and mouse T lymphocytes using RNA electroporation. Mol Ther. 2005;13:151–159. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.07.688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhao Y, Zheng Z, Robbins PF, et al. Primary human lymphocytes transduced with NY-ESO-1 antigen-specific TCR genes recognize and kill diverse human tumor cell lines. J Immunol. 2005;174:4415–4423. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.7.4415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Feuillet V, Lucas B, Di Santo JP, et al. Multiple survival signals are delivered by dendritic cells to naive CD4(+) T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:2563–2572. doi: 10.1002/eji.200526127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lokshin AE, Kalinski P, Sassi RR, et al. Differential regulation of maturation and apoptosis of human monocyte-derived dendritic cells mediated by MHC class II. Int Immunol. 2002;14:1027–1037. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxf073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McLellan A, Heldmann M, Terbeck G, et al. MHC class II and CD40 play opposing roles in dendritic cell survival. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:2612–2619. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200009)30:9<2612::AID-IMMU2612>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Matsuoka T, Tabata H, Matsushita S. Monocytes are differentially activated through HLA-DR, -DQ, and -DP molecules via mitogen-activated protein kinases. J Immunol. 2001;166:2202–2208. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.4.2202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Koch F, Stanzl U, Jennewein P, et al. High level IL-12 production by murine dendritic cells: upregulation via MHC class II and CD40 molecules and downregulation by IL-4 and IL-10. J Exp Med. 1996;184:741–746. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.2.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gershon RK. A disquisition on suppressor T cells. Transplant Rev. 1975;26:170–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1975.tb00179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shevach EM, McHugh RS, Piccirillo CA, et al. Control of T-cell activation by CD4+ CD25+ suppressor T cells. Immunol Rev. 2001;182:58–67. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2001.1820104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.North RJ. Cyclophosphamide-facilitated adoptive immunotherapy of an established tumor depends on elimination of tumor-induced suppressor T cells. J Exp Med. 1982;155:1063–1074. doi: 10.1084/jem.155.4.1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shimizu J, Yamazaki S, Sakaguchi S. Induction of tumor immunity by removing CD25+CD4+ T cells: a common basis between tumor immunity and autoimmunity. J Immunol. 1999;163:5211–5218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Onizuka S, Tawara I, Shimizu J, et al. Tumor rejection by in vivo administration of anti-CD25 (interleukin-2 receptor alpha) monoclonal antibody. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3128–3133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Daniels GA, Sanchez-Perez L, Diaz RM, et al. A simple method to cure established tumors by inflammatory killing of normal cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:1125–1132. doi: 10.1038/nbt1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sutmuller RP, van Duivenvoorde LM, van Elsas A, et al. Synergism of cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 blockade and depletion of CD25(+) regulatory T cells in antitumor therapy reveals alternative pathways for suppression of auto-reactive cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses. J Exp Med. 2001;194:823–832. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.6.823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ghiringhelli F, Larmonier N, Schmitt E, et al. CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells suppress tumor immunity but are sensitive to cyclophosphamide which allows immunotherapy of established tumors to be curative. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:336–344. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Powell DJ, Jr, Parker LL, Rosenberg SA. Large-scale depletion of CD25+ regulatory T cells from patient leukapheresis samples. J Immunother. 2005;28:403–411. doi: 10.1097/01.cji.0000170363.22585.5a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kuball J, Schmitz FW, Voss RH, et al. Cooperation of human tumor-reactive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells after redirection of their specificity by a high-affinity p53A2.1-specific TCR. Immunity. 2005;22:117–129. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]