Abstract

The accumulation of neutrophils at sites of tissue injury or infection is mediated by chemotactic factors released as part of the inflammatory process. Some of these factors are generated as a direct consequence of tissue injury or infection, including degradation fragments of connective tissue collagen and bacterial- or viral-derived peptides containing collagen-related structural motifs. In these studies, we examined biochemical mechanisms mediating the biologic activity of synthetic polypeptides consisting of repeated units of proline (Pro), glycine (Gly), and hydroxyproline (Hyp), major amino acids found within mammalian and bacterial collagens. We found that the peptides were chemoattractants for neutrophils. Moreover, their chemotactic potency was directly related to their size and composition. Thus, the pentameric peptides (Pro-Pro-Gly)5 and (Pro-Hyp-Gly)5 were more active in inducing chemotaxis than the corresponding decameric peptides (Pro-Pro-Gly)10 and (Pro-Hyp-Gly)10. In addition, the presence of Hyp in peptides reduced chemotactic activity. The synthetic peptides were also found to reduce neutrophil apoptosis. In contrast to chemotaxis, this activity was independent of peptide size or composition. The effects of the peptides on both chemotaxis and apoptosis were blocked by inhibitors of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3-K) and p38 mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase. However, only (Pro-Pro-Gly)5 and (Pro-Pro-Gly)10 induced expression of PI3-K and phosphorylation of p38 MAP kinase, suggesting a potential mechanism underlying reduced chemotactic activity of Hyp-containing peptides. Although none of the synthetic peptides tested had any effect on intracellular calcium mobilization, each induced nuclear binding activity of the transcription factor NF-κB. These findings indicate that polymeric polypeptides containing Gly-X-Y collagen-related structural motifs promote inflammation by inducing chemotaxis and blocking apoptosis. However, distinct calcium-independent signaling pathways appear to be involved in these activities.

BACKGROUND

The inflammatory response is characterized by an accumulation of neutrophils at sites of tissue injury and infection. Neutrophils respond to chemotactic factors including connective tissue degradation products, leukotriene B4, and bacterially-derived formylmethionine-leucine-phenylalanine (fMLP), released from damaged tissue or by invading pathogens. In previous studies we demonstrated that collagenase or cyanogen bromide digests of native collagen, as well as synthetic collagen-like polypeptides containing glycine (Gly), proline (Pro), and hydroxyproline (Hyp) are potent chemoattractants for human neutrophils [1, 2, 3]. These polypeptides also activated macrophages to release neutrophil chemokines [4]. The present studies were aimed at analyzing mechanisms mediating the biological activity of collagen degradation products using synthetic polypeptides as a model. Synthetic polypeptides are similar to degradation products generated from mammalian collagen and/or to collagen-related structural motifs produced by bacteria and viruses [5]. The use of synthetic model peptides of varying length and composition allowed us to perform structure-activity studies.

Chemoattractants such as fMLP and interleukin-8 (IL-8) initiate their biological activity by binding to specific cell surface receptors. For most chemoattractants, this is followed by mobilization of intracellular calcium, activation of protein kinases, and translocation and binding of transcription factors to consensus sequences in promoter regions of genes regulating the inflammatory response [6, 7, 8]. We speculated that variations in the activity of the synthetic peptides may be related to their distinct ability to activate these signaling pathways.

METHODS

Reagents

The synthetic polypeptides (Pro-Pro-Gly)5, (Pro-Pro-Gly)10, (Pro-Hyp-Gly)5, and (Pro-Hyp-Gly)10 were purchased from Peptides International (Louisville, Ky). Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS) and fMLP were obtained from Sigma (St Louis, Mo). LY 294002 was from Calbiochem (La Jolla, Calif) and SB 203580 from Biomol (Plymouth Meeting, Pa). Indo-1 acetoxymethyl ester (Indo-1 AM) was purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, Ore) and stored as a 1 mM stock solution in dimethylsufoxide at −20°C. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against NF-κB-p50, NF-κB-p65, and p38 MAP kinase, as well as horseradish peroxidase-(HRP-)linked secondary antibodies, were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, Calif). Mouse monoclonal anti-phospho-p38 MAP kinase (Thr180/Tyr182) antibody (IgG1) was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, Mass), and mouse monoclonal anti-phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3-K) (p85-subunit-reactive) antibody from BD Biosciences PharMingen (San Diego, Calif). Double-stranded DNA probes used for electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) were obtained from IDT Technologies (Coralville, Iowa). FITC-linked Annexin V was from R & D Systems (Minneapolis, Minn), and propidium iodide from Calbiochem (San Diego, Calif).

Cell isolation

Human neutrophils were isolated from heparinized peripheral venous blood by dextran sedimentation and Ficoll density gradient centrifugation as previously described [9]. These studies were approved by the Institutional Review Board of UMDNJ Robert Wood Johnson Medical School.

Measurement of chemotaxis

Migration of neutrophils through nucleopore polycarbonate filters was assayed using the modified Boyden chamber technique [10]. For our studies we used a 48-well microchemotaxis chamber (Neuro Probe, Inc, Pleasanton, Calif). Thirty microliters of synthetic peptides, fMLP (5 × 10−8 M), or medium control were placed in each well of the lower chamber. A 5-μm pore-size filter was then placed over the wells and the upper chamber set into place. Fifty microliters of a neutrophil suspension (1 × 105cells) in HBSS containing 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 2.4 mg/ml HEPES, pH 7.2, was added to each well. After incubation for 45 minutes at 37°C, the filter containing adhered, migrated neutrophils was removed and stained with Wright-Giemsa. Chemotaxis was quantified as the number of cells that migrated through the filter in 10 oil immersion fields. In some experiments, cells were incubated at room temperature with LY 294002 (50 μM, 5 minutes) or SB 203580 (30 μM, 1 hour) prior to the analysis of chemotactic responsiveness.

Measurement of intracellular calcium

Indo-1 AM was used to measure intracellular calcium mobilization [11]. Neutrophils were inoculated into Nunc coverglass chambers (2 × 106 cells/chamber) and allowed to adhere overnight. Cells were then washed with HBSS containing 0.3% BSA and incubated in 1 μM Indo-1 AM at 37°C. After 30 minutes, the cells were washed three times and 1 mL of HBSS containing 0.3% BSA was added to each well. Intracellular calcium was quantified on a Meridian ACAS 570 Anchored Cell Analysis System (Okemos, Mich) equipped with an Innova 90 5-W laser adjusted to an output of 100 mW. For measurement of cellular fluorescence, Indo-1 was excited using the ultraviolet lines (351–364 nm) of the argon laser. Calcium mobilization was quantified by scanning single 130 × 130 μm fields containing ≥ 15 cells every 8 seconds for a total of 5 minutes and collecting the emissions at 485 nm (calcium-free Indo-1) and 405 nm (calcium-saturated Indo-1). Data are presented as the ratio of emission at 405 nm relative to 485 nm. Synthetic peptides (10 nM) or fMLP (5 × 10−8 M) were added to the cells 180 seconds after stable baselines were established.

Western blot analysis

Neutrophils were incubated (37°C) with medium control, fMLP (5 × 10−8 M), or 10 nM (Pro-Pro-Gly)5, (Pro-Pro-Gly)10, (Pro-Hyp-Gly)5, or (Pro-Hyp-Gly)10 for 2 hours (PI3-K) or 5 minutes (p38, phospho-p38). Cells were then solubilized in buffer containing 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 1 μg/mL pepstatin A, 1 μg/mL leupeptin, 10 μg/mL soybean trypsin inhibitor, 10 μg/mL aprotinin, and 1% Triton X-100. After 10 minutes in ice, lysates were centrifuged (4000 xg, 5 minutes) and protein concentrations in the supernatants were quantified using a BCA Protein Assay Kit (Pierce, Rockford, Ill) with BSA as the standard. Aliquots of supernatants containing 10 μg of protein were fractionated on 7.5% SDS polyacrylamide gels and electroblotted onto 0.45 μm nitrocellulose paper (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif) at 250 mA for 4 hours in a Mini Trans-Blot Electrophoretic Transfer Cell (Bio-Rad) in 25 mM Tris, pH 8.3, 192 mM Gly, 20% (v/v) methanol. Blots were then incubated in a 1 : 250 dilution of anti-phospho-p38 MAP kinase antibody, anti-p38 MAP kinase, or anti-PI3-K antibody. After washing, the blots were incubated with goat antimouse IgG (1 : 2000) or sheep antirabbit IgG (1 : 1000) HRP-conjugated antibodies for 1 hour at room temperature. Proteins were detected using a Renaissance Western Blot Chemiluminescence Reagent Plus kit (NEN Life Sciences, Boston, Mass).

Measurement of neutrophil apoptosis

Neutrophils were washed in PBS, resuspended in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum, and incubated in a shaking water bath at 37°C for 24 hours in the presence or absence of peptides (10 nM). Cells were then centrifuged, resuspended (2 × 106 cells/mL) in binding buffer (10 mM HEPES/NaOH, pH 7.4, 140 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM CaCl2), and incubated (15 minutes, room temperature) with Annexin V and propidium iodide. Samples were analyzed by flow cytometry on a Coulter EPICS Profile II (Hialeah, Fla). Viable, apoptotic, and necrotic neutrophil populations were gated electronically and data analyzed using quadrant statistics based on relative Annexin V and propidium iodide fluorescence [12].

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

To prepare nuclear extracts, neutrophils (2 × 106) were microcentrifuged for 15 seconds and then resuspended in 400 μL of cold buffer (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 10 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM EGTA, 1 mM DTT, 0.5 mM PMSF). After 15 minutes in ice, 25 μL of a 10% solution of NP-40 was added, and the sample mixed on a vortex for 10 seconds. The lysates were then centrifuged for 30 seconds in a microfuge, the nuclear pellets resuspended in 50 μL of ice-cold buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 0.4 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF) and placed on a rocker platform at 4°C for 15 minutes. The sample was then microcentrifuged for 5 minutes at 4°C and the resulting soluble nuclear extracts were collected. Double-stranded probes containing an NF-κB (AGTTGAGGGGACCGCCCGCGGCCCGT) consensus sequence were labeled with (γ-32P)-dCTP. For binding reactions, nuclear extracts (50 μg of protein) were incubated for 15 minutes at room temperature with labeled probe in buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 40 mM NaCl, 10 mM EDTA, 1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.1% NP-40, 4% glycerol, and 0.1 μg/μL poly. (dI-dC)poly. (dI-dC) (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ). For competitive binding assays, nuclear extracts were incubated with a 100-fold excess unlabeled probe. Supershift assays were performed by incubation of the samples with polyclonal antibodies to p50 or p65 (1 μg/60 μL reaction volume) for 1 hour prior to the addition of the labeled probe. Samples were electrophoresed on 4% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gels in buffer (0.04 M Tris-acetate, 0.001 M EDTA, pH 8.0) at 15 V/cm. Gels were then dried and autoradiographed.

RESULTS

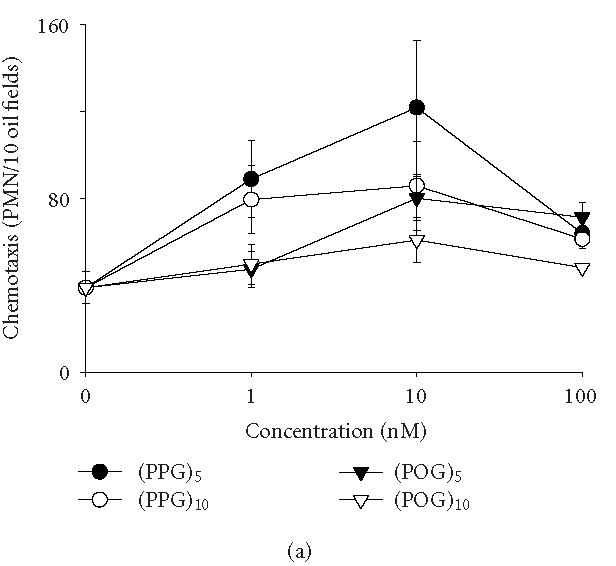

We have previously demonstrated that synthetic pentameric peptides consisting of Pro and Gly, or Pro, Hyp, and Gly are chemoattractants for neutrophils [1, 2, 3]. Figure 1 shows that the chemotactic activity of these peptides is dose related, reaching a maximum at 10 nM. Increasing the length of the peptides from five to ten repeated units reduced their chemotactic activity. At concentrations of 1 and 10 nM, peptides consisting of Pro, Gly, and Hyp were less chemotactic than peptides consisting of only Pro and Gly. At optimal concentrations, (Pro-Pro-Gly)5, the most potent of the synthetic peptides, was approximately 60% less active than fMLP in inducing chemotaxis (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Induction of chemotaxis by synthetic polypeptides. Neutrophil chemotaxis was assayed using microwell chambers. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM of 3–4 experiments. Background levels of migration were subtracted from each value. (a) Dose-dependent effects of peptides on neutrophil chemotaxis. (b) Cells were incubated with medium control, the p38 MAP kinase inhibitor SB 203580 (30 μM, 1 hour) or the PI3-K inhibitor LY 294002 (50 μM, 5 minutes) prior to the analysis of chemotactic responsiveness to polypeptides (10 nM). (Pro-Pro-Gly)n, (PPG)n; (Pro-Hyp-Gly)n, (POG)n.

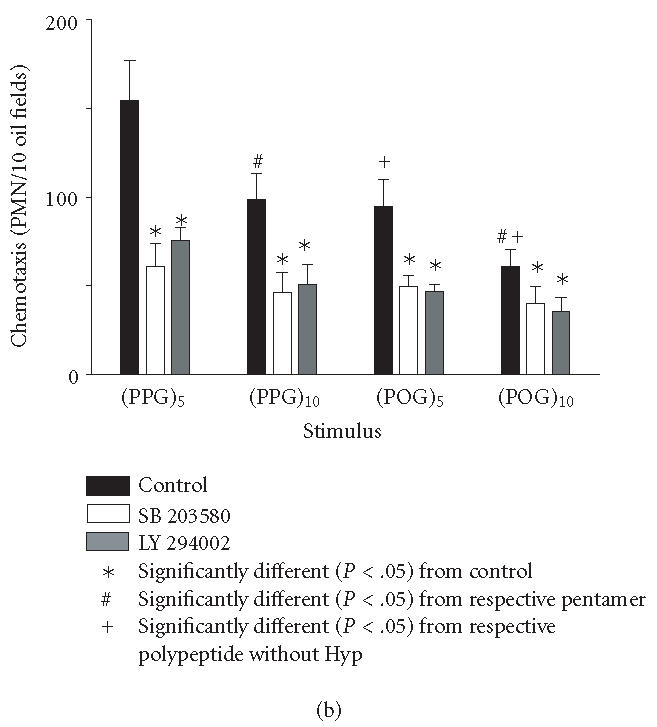

Activated neutrophils are cleared from inflamed sites by the process of apoptosis, followed by macrophage phagocytosis. This leads to resolution rather than persistence of tissue injury. Chemoattractants such as fMLP promote inflammation by activating neutrophils and prolonging the survival of these cells in tissues by blocking apoptosis [13]. In further studies, we analyzed the effects of synthetic polymeric peptides on neutrophil apoptosis. One of the earliest signs of apoptosis is translocation of phosphatidylserine (PS) from the inner to the outer surface of the plasma membrane, which can be detected by Annexin V binding [14]. Approximately 30% of neutrophils was found to undergo spontaneous apoptosis after 24 hours in culture (Figure 2). This activity was significantly reduced in the presence of the polypeptides. The effects of the synthetic peptides were similar to fMLP. In contrast to chemotaxis, no differences were noted in the antiapoptotic activity of collagen-like peptides in terms of their size or composition.

Figure 2.

Measurement of neutrophil apoptosis. Cells were incubated in a shaking water bath (37°C) in the presence or absence of fMLP (5 × 10−8 M), synthetic polypeptides, SB 203580, or LY 294002 for 24 hours and then labeled with Annexin V and propidium iodide and analyzed by flow cytometry. Data were analyzed using Coulter quadrant statistics based on relative fluorescence binding of Annexin V and propidium iodide. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM of 3–4 experiments. Significantly different (P < .05) from control.

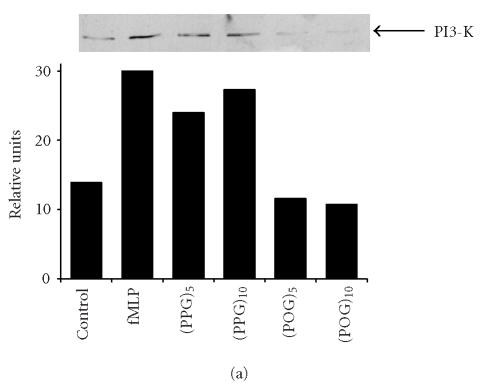

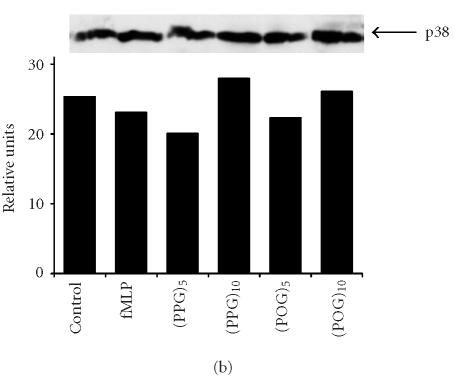

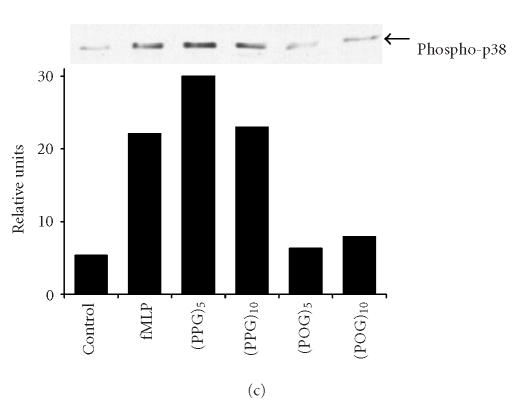

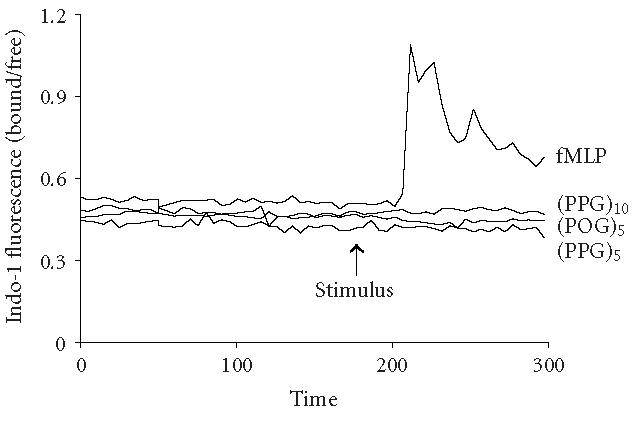

We next investigated potential biochemical signaling pathways mediating the biologic activity of these peptides in neutrophils. For comparative purposes, we also evaluated the response of the cells to fMLP. Treatment of neutrophils with fMLP caused a rapid and transient increase in intracellular calcium, which was evident within 30 seconds (Figure 3). In contrast, none of the synthetic polypeptides induced calcium mobilization in neutrophils. PI3-K catalyzes the formation of phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-triphosphate and plays a key role in neutrophil activation and chemotaxis [15, 16]. Low levels of PI3-K protein were detectable in unstimulated neutrophils (Figure 4a). Treatment of the cells with pentameric peptides consisting of Pro and Gly resulted in a twofold increase in PI3-K. This was evident after 2 hours and was similar to the response observed with fMLP. In contrast, the pentameric peptide containing Hyp had no effect on PI3-K, and increasing the length of the peptides from 5 to 10 repeated units did not alter the quantity of PI3-K detected. To analyze the role of PI3-K in collagen peptide-induced chemotaxis and apoptosis, cells were treated with LY 294002 [17]. This PI3-K inhibitor was found to reduce chemotaxis induced by fMLP, (Pro-Pro-Gly)5 and (Pro-Pro-Gly)10, as well as (Pro-Hyp-Gly)5, and (Pro-Hyp-Gly)10 by 50% (Figure 1b, data not shown). No major differences were noted in the sensitivity of the peptides to the PI3-K inhibitor. Similarly, LY 294002 was found to block the inhibitory effects of both fMLP and synthetic peptides on apoptosis. As observed with chemotaxis, no differences were observed in the sensitivity of the antiapoptotic effects of the peptides to PI3-K inhibition (Figure 2, data not shown). In the absence of these peptides, LY 294002 had no effect on chemotaxis or apoptosis.

Figure 3.

Effects of synthetic polypeptides on calcium mobilization. Neutrophils were incubated with Indo-1 (1 μM). After establishing a stable baseline, 10 nM (Pro-Pro-Gly)5, (Pro-Pro-Gly)10, (Pro-Hyp-Gly)5, or fMLP was added (arrow) to the cells. Calcium mobilization is indicated by an increase in the Indo-1 fluorescence ratio. Each graph represents the average change in ratio in a field containing not less than 15 cells.

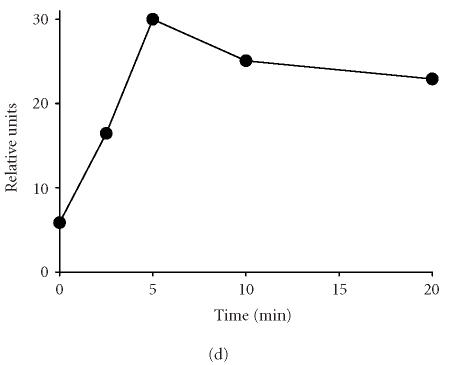

Figure 4.

Effects of synthetic polypeptides on PI3-K and p38 MAP kinase expression. Neutrophils were incubated (37°C) with medium control, fMLP (5 × 10−8 M), or 10 nM (Pro-Pro-Gly)5, (Pro-Pro-Gly)10, (Pro-Hyp-Gly)5, or (Pro-Hyp-Gly)10 for 2 hours (PI3-K) or 5 minutes (p38, phospho-p38). (a) PI3-K, (b) p38, (c) phospho-p38, (d) protein expressions were measured using western blotting and quantified by densitometry. Time course of phospho-p38 protein expression in response to (Pro-Pro-Gly)5. Western blots were scanned by densitometry and data presented as relative intensity units. One representative experiment of 3 is shown for each analysis.

Recent studies have implicated MAP kinases in chemoattractant-induced signaling and in PI3-K activation in neutrophils [18, 19, 20]. We found that untreated neutrophils expressed relatively large quantities of total p38 MAP kinase protein (Figure 4b). Expression of this protein was unaltered by fMLP or by synthetic polypeptides. In contrast, only low levels of phospho-p38 MAP kinase were detected in unstimulated neutrophils, and this was markedly increased in response to fMLP, as well as (Pro-Pro-Gly)5 and (Pro-Pro-Gly)10 (Figure 4c). The effects of these peptides on phospho-p38 expression were rapid, peaking 5 minutes after treatment and persisting for at least 20 minutes (Figure 4d, data not shown). Treatment of neutrophils with peptides containing Hyp had no significant effect on phospho-p38 protein expression (Figure 4c). Pretreatment of the cells with SB 203580, a p38 MAP kinase inhibitor [21], was found to significantly reduce chemotaxis induced by (Pro-Pro-Gly)5 and (Pro-Pro-Gly)10, as well as (Pro-Hyp-Gly)5, and (Pro-Hyp-Gly)10 (Figure 1b). Similarly, SB 203580 blocked the effects of fMLP and synthetic peptides on apoptosis, indicating that this response is also p38 MAP kinase-dependent (Figure 2, data not shown).

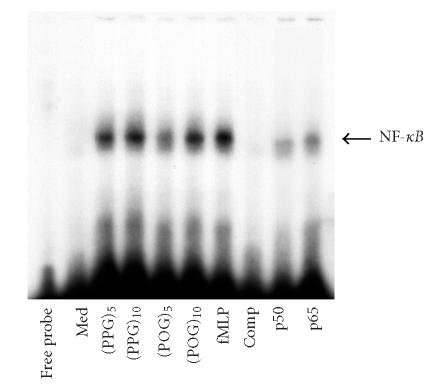

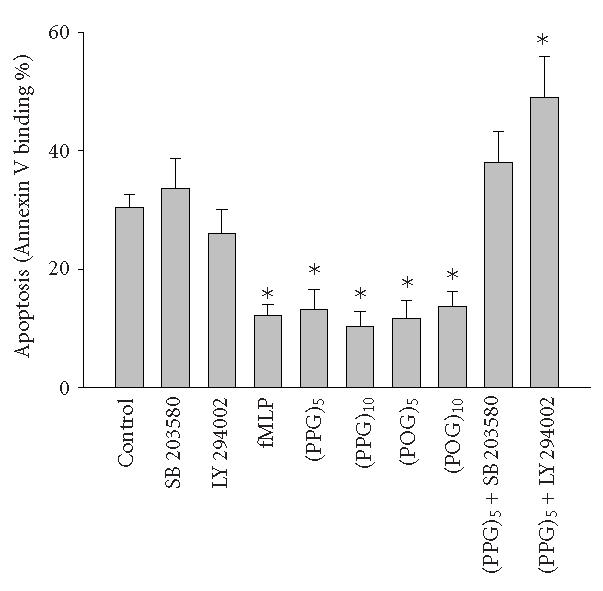

The transcription factor NF-κB is known to be activated by chemoattractants through MAP kinases [22]. We found that each of the synthetic peptides, like fMLP, induced nuclear binding of NF-κB (Figure 5). This response was independent of peptide length or composition. Supershift assays revealed that the NF-κB complex contained both p50 and p65 (not shown). Preincubation of nuclear extracts with excess unlabeled probe competitively reduced binding of the labeled probe, demonstrating its specificity.

Figure 5.

Effects of synthetic polypeptides on NF-κB nuclear binding activity. Neutrophils (1 × 106/mL) were treated with medium control (Med), synthetic peptides (10 nM), or fMLP (5 × 10−8 M) for 30 minutes. Nuclear extracts (50 μg of protein) were analyzed for NF-κB binding activity using a gel retardation assay. Extracts, prepared from fMLP-treated cells were incubated in ice for 1 hour with antibodies to the p50 or p65 subunits of NF-κB (1 μg), or 100-fold excess unlabeled cold competitor (Comp) prior to the labeled probe.

DISCUSSION

Neutrophil chemotaxis and survival are regulated by inflammatory mediators that are present at sites of infection or injury. Whereas proinflammatory mediators promote chemotaxis and block apoptosis, antiinflammatory cytokines are proapoptotic and abrogate the chemotactic response. Coordinate regulation of chemotaxis and survival allows for the persistence of neutrophils at sites of injury, as well as effective termination of the inflammatory response [23]. The present studies demonstrate that synthetic peptides containing collagen-like structural motifs induce chemotaxis and reduce apoptosis in neutrophils. These results are consistent with a proinflammatory role of these peptides. This is supported by reports that synthetic collagen-like peptides also stimulate oxidative metabolism and macrophage release of neutrophil chemokines [4, 24]. Tissue injury is associated with breakdown of interstitial connective tissue. Our findings that peptides containing collagen-like structural motifs exhibit proinflammatory activity suggests that they may play a role in amplifying acute immunological responses to infection or injury.

Consistent with previous studies [2, 3], we found that the chemotactic activity of the synthetic polypeptides was directly related to their size and composition. Thus, larger peptides containing ten repeated subunits were less active than those containing five subunits. Moreover, peptides consisting of Pro, Gly, and Hyp were less chemotactic than peptides consisting of only Pro and Gly. In contrast, although each of the peptides markedly reduced neutrophil apoptosis, these effects were independent of peptide size or structure. These data suggest that collagen peptide-induced chemotaxis and apoptosis involve distinct receptors and/or signaling mechanisms.

One early step in the signaling pathway induced by chemoattractants is mobilization of intracellular Ca++ [25, 26]. In contrast to fMLP, the synthetic peptides had no effect on calcium mobilization in human neutrophils. These findings suggest that the chemotactic and antiapoptotic actions of these peptides do not require changes in intracellular calcium. This is consistent with reports of other proinflammatory mediators that alter neutrophil chemotaxis and apoptosis by mechanisms independent of intracellular calcium shifts, including transforming growth factor-β1, soluble Fas ligand, immune complexes, and the antineutrophil antibody, DL1.2 [27, 28, 29, 30]. Our findings suggest that the requirement for increases in intracellular calcium for induction of biological activity depends on the chemoattractant.

Activation of protein kinases including PI3-K and p38 MAP kinase is thought to play a critical role in chemoattractant-induced signaling leading to biologic responses [19, 20, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36]. Consistent with this idea, we found that the effects of the synthetic peptides on chemotaxis and apoptosis were dependent on both PI3-K and p38 MAP kinase activity. Thus, LY 294002 and SB 203580, inhibitors of PI3-K and p38 MAP kinase, respectively, blocked both the chemotactic and antiapoptotic activity of each of the peptides. However, whereas (Pro-Pro-Gly)5 and (Pro-Pro-Gly)10 induced PI3-K and phospho-p38 expression in neutrophils, (Pro-Hyp-Gly)5 and (Pro-Hyp-Gly)10 had no effect on these proteins. Peptides containing Hyp were also less potent chemoattractants than peptides containing only Pro and Gly. These findings suggest that the relative chemotactic potency of these peptides may be related to their efficacy in upregulating PI3-K and p38 MAP kinase. Alternatively, fMLP, (Pro-Pro-Gly)5, and (Pro-Pro-Gly)10 may induce rapid alterations in the subcellular localization of PI3-K protein in neutrophils, leading to increased accessibility and detection by immunoblotting. In contrast, this does not appear to be the case for apoptosis. Thus, an inability to induce PI3-K or phospho-p38 MAP kinase had no effect on the antiapoptotic activity of Hyp-containing peptides. The observation that the antiapoptotic effects of (Pro-Hyp-Gly)5 and (Pro-Hyp-Gly)10 were blocked by PI3-K and p38 MAP kinase inhibitors indicates that these signaling pathways are nevertheless essential for this response. However, they appear to be activated distinctly by (Pro-Pro-Gly)n and (Pro-Hyp-Gly)n peptides.

Previous studies have suggested that PI3-K-mediated responses induced by chemoattractants involve mobilization of intracellular calcium through activation of phospholipase C [37]. Alterations in cytosolic Ca2+ are also important in inducing p38 MAP kinase activity in neutrophils [38]. In contrast, our findings indicate that synthetic peptide-induced activation of PI3-K and p38 MAP kinase, leading to chemotaxis and reduced apoptosis, occurs though calcium-independent pathways. It is possible that phosphoinositides, or phosphorylated protein products of PI3-K or p38 MAP kinase, interact directly with actin-binding proteins, resulting in directed migration of the cells [39]. p38 MAP kinase is also known to phosphorylate proteins that may regulate chemotaxis and apoptosis by calcium-independent mechanisms, including MAP kinase-activated proteins 2, 3, and 5, as well as the transcription factors ATF-2 and CHOP-1 [40].

Signaling via PI3-K and p38 MAP kinase leads to the activation of the transcription factor NF-κB, which is known to regulate genes involved in inflammatory responses to tissue injury [41]. NF-κB has been reported to be involved in chemoattractant-induced neutrophil activation as well as the suppression of apoptosis [22, 42]. Moreover, mice lacking the NF-κB subunit c-Rel are resistant to collagen-induced arthritis, and inhibition of NF-κB blocks neutrophil migration into damaged lungs in vivo [43, 44, 45]. We found that peptides containing collagen-related structural motifs induced NF-κB nuclear binding activity in neutrophils. However, no significant differences in activity were observed based on the size or composition of the peptides. These findings are consistent with the antiapoptotic effects of these synthetic peptides and suggest that the chemotactic and antiapoptotic effects of the peptides involve distinct signaling pathways leading to NF-κB activation.

CONCLUSIONS

Polymeric polypeptides containing collagen-related structural motifs promote inflammation by inducing chemotaxis and blocking apoptosis. However, distinct calcium-independent signaling pathways appear to be involved in these activities. Neutrophil chemotaxis and apoptosis are a key to initiating and controlling inflammation. The accumulation and persistence of these cells in tissues in response to protein fragments generated by invasive pathogens or by the degradation of connective tissue collagen may exacerbate injury. An understanding of the mechanisms mediating these processes is essential in developing strategies for limiting maladaptive inflammatory responses.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants HD42036, ES05022, GM34310, ES04738, GM34310, HL67708, and CA100994.

References

- 1.Laskin DL, Kimura T, Sakakibara S, Riley DJ, Berg RA. Chemotactic activity of collagen-like polypeptides for human peripheral blood neutrophils. J Leukoc Biol. 1986;39(3):255–266. doi: 10.1002/jlb.39.3.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laskin DL, Berg RA. Chemotactic Properties of Synthetic Collagen-Like Peptides in Leukocytes and Host Defense. New York, NY, USA: Alan R Liss; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riley DJ, Kerr JS, Guss HN, Curran SF, Laskin DL, Berg RA. Intratracheal instillation of collagen peptides induces a neutrophil influx in rat lungs. Trans Assoc Am Physicians. 1984;97:290–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laskin DL, Soltys RA, Berg RA, Riley DJ. Activation of neutrophils by factors released from alveolar macrophages stimulated with collagen-like polypeptides. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1990;2(5):463–470. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/2.5.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rasmussen M, Jacobsson M, Bjorck L. Genome-based identification and analysis of collagen-related structural motifs in bacterial and viral proteins. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(34):32313–32316. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304709200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nick JA, Avdi NJ, Young SK, et al. Common and distinct intracellular signaling pathways in human neutrophils utilized by platelet activating factor and FMLP. J Clin Invest. 1997;99(5):975–986. doi: 10.1172/JCI119263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McDonald PP, Bald A, Cassatella MA. Activation of the NF-κB pathway by inflammatory stimuli in human neutrophils. Blood. 1997;89(9):3421–3433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McDonald PP, Cassatella MA. Activation of transcription factor NF-kappa B by phagocytic stimuli in human neutrophils. FEBS Lett. 1997;412(3):583–586. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00857-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferrante A, Thong YH. Optimal conditions for simultaneous purification of mononuclear and polymorphonuclear leucocytes from human blood by the Hypaque-Ficoll method. J Immunol Methods. 1980;36(2):109–117. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(80)90036-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boyden S. The chemotactic effect of mixtures of antibody and antigen on polymorphonuclear leucocytes. J Exp Med. 1962;115:453–466. doi: 10.1084/jem.115.3.453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J Biol Chem. 1985;260(6):3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moore A, Donahue CJ, Bauer KD, Mather JP. Simultaneous measurement of cell cycle and apoptotic cell death. Methods Cell Biol. 1998;57:265–278. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)61584-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watson RW, Rotstein OD, Nathens AB, Parodo J, Marshall JC. Neutrophil apoptosis is modulated by endothelial transmigration and adhesion molecule engagement. J Immunol. 1997;158(2):945–953. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sgonc R, Gruber J. Apoptosis detection: an overview. Exp Gerontol. 1998;33(6):525–533. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(98)00031-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coffer PJ, Geijsen N, M'rabet L, et al. Comparison of the roles of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signal transduction in neutrophil effector function. Biochem J. 1998;329(1):121–130. doi: 10.1042/bj3290121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pan ZK, Chen LY, Cochrane CG, Zuraw BL. fMet-Leu-Phe stimulates proinflammatory cytokine gene expression in human peripheral blood monocytes: the role of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. J Immunol. 2000;164(1):404–411. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.1.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vlahos CJ, Matter WF, Hui KY, Brown RF. A specific inhibitor of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, 2-(4-morpholinyl)-8-phenyl-4H-1-benzopyran-4-one (LY294002) J Biol Chem. 1994;269(7):5241–5248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hii CS, Stacey K, Moghaddami N, Murray AW, Ferrante A. Role of the extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase cascade in human neutrophil killing of Staphylococcus aureus and Candida albicans and in migration. Infect Immun. 1999;67(3):1297–1302. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.3.1297-1302.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heuertz RM, Tricomi SM, Ezekiel UR, Webster RO. C-reactive protein inhibits chemotactic peptide-induced p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activity and human neutrophil movement. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(25):17968–17974. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.25.17968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zu YL, Qi J, Gilchrist A, et al. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation is required for human neutrophil function triggered by TNF-α or FMLP stimulation. J Immunol. 1998;160(4):1982–1989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cuenda A, Rouse J, Doza YN, et al. SB 203580 is a specific inhibitor of a MAP kinase homologue which is stimulated by cellular stresses and interleukin-1. FEBS Lett. 1995;364(2):229–233. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00357-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelher MR, Ambruso DR, Elzi DJ, et al. Formyl-Met-Leu-Phe induces calcium-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation of Rel-1 in neutrophils. Cell Calcium. 2003;34(6):445–455. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(03)00067-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Savill J. Apoptosis in resolution of inflammation. J Leukoc Biol. 1997;61(4):375–380. doi: 10.1002/jlb.61.4.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laskin DL, Soltys RA, Berg RA, Riley DJ. Activation of alveolar macrophages by native and synthetic collagen-like polypeptides. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1994;10(1):58–64. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.10.1.8292381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krause KH, Campbell KP, Welsh MJ, Lew DP. The calcium signal and neutrophil activation. Clin Biochem. 1990;23(2):159–166. doi: 10.1016/0009-9120(90)80030-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu D, Huang CK, Jiang H. Roles of phospholipid signaling in chemoattractant-induced responses. J Cell Sci. 2000;113(17):2935–2940. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.17.2935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hannigan M, Zhan L, Ai Y, Huang CK. The role of p38 MAP kinase in TGF-beta1-induced signal transduction in human neutrophils. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;246(1):55–58. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ottonello L, Tortolina G, Amelotti M, Dallegri F. Soluble Fas ligand is chemotactic for human neutrophilic polymorphonuclear leukocytes. J Immunol. 1999;162(6):3601–3606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weinberger B, Laskin DL, Mariano TM, et al. Mechanisms underlying reduced responsiveness of neonatal neutrophils to distinct chemoattractants. J Leukoc Biol. 2001;70(6):969–976. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gamberale R, Giordano M, Trevani AS, Andonegui G, Geffner JR. Modulation of human neutrophil apoptosis by immune complexes. J Immunol. 1998;161(7):3666–3674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ma AD, Metjian A, Bagrodia S, Taylor S, Abrams CS. Cytoskeletal reorganization by G protein-coupled receptors is dependent on phosphoinositide 3-kinase gamma, a Rac guanosine exchange factor, and Rac. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18(8):4744–4751. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.8.4744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Knall C, Worthen GS, Johnson GL. Interleukin 8-stimulated phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase activity regulates the migration of human neutrophils independent of extracellular signal-regulated kinase and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(7):3052–3057. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Naccache PH, Levasseur S, Lachance G, Chakravarti S, Bourgoin SG, McColl SR. Stimulation of human neutrophils by chemotactic factors is associated with the activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase γ. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(31):23636–23641. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001780200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilcox RA, Primrose WU, Nahorski SR, Challiss RA. New developments in the molecular pharmacology of the myo-inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1998;19(11):467–475. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(98)01260-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang KY, Arcaroli J, Kupfner J, et al. Involvement of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase gamma in neutrophil apoptosis. Cell Signal. 2003;24(2):225–233. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(02)00063-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nick JA, Young SK, Brown KK, et al. Role of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in a murine model of pulmonary inflammation. J Immunol. 2000;164(4):2151–2159. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.4.2151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Siddiqui RA, English D. Phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase-mediated calcium mobilization regulates chemotaxis in phosphatidic acid-stimulated human neutrophils. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1483(1):161–173. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(99)00172-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Elzi DJ, Bjornsen AJ, MacKenzie T, Wyman TH, Silliman CC. Ionomycin causes activation of p38 and p42/44 mitogen-activated protein kinases in human neutrophils. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;281(1):C350–C360. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.281.1.C350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Defacque H, Egeberg M, Habermann A, et al. Involvement of ezrin/moesin in de novo actin assembly on phagosomal membranes. EMBO J. 2000;19(2):199–212. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.2.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cara DC, Kaur J, Forster M, McCafferty DM, Kubes P. Role of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in chemokine-induced emigration and chemotaxis in vivo. J Immunol. 2001;167(11):6552–6558. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.11.6552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Funakoshi M, Sonoda Y, Tago K, Tominaga S, Kasahara T. Differential involvement of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and phosphatidyl inositol 3-kinase in the IL-1-mediated NF-κ B and AP-1 activation. Int Immunopharmacol. 2001;1(3):595–604. doi: 10.1016/s1567-5769(00)00035-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ward C, Chilvers ER, Lawson MF, et al. Nf-κ B activation is a critical regulator of human granulocyte apoptosis in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(7):4309–4318. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.7.4309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Campbell IK, Gerondakis S, O'Donnell K, Wicks IP. Distinct roles for the NF-kappaB1 (p50) and c-Rel transcription factors in inflammatory arthritis. J Clin Invest. 2000;105(12):1799–1806. doi: 10.1172/JCI8298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Blackwell TS, Blackwell TR, Holden EP, Christman BW, Christman JW. In vivo antioxidant treatment suppresses nuclear factor-kappa B activation and neutrophilic lung inflammation. J Immunol. 1996;157(4):1630–1637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Blackwell TS, Blackwell TR, Christman JW. Impaired activation of nuclear factor-κB in endotoxin-tolerant rats is associated with down-regulation of chemokine gene expression and inhibition of neutrophilic lung inflammation. J Immunol. 1997;158(12):5934–5940. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]