Abstract

Previous studies have found beneficial effects of aromatherapy massage for agitation in people with dementia, for pain relief and for poor sleep. Children with autism often have sleep difficulties, and it was thought that aromatherapy massage might enable more rapid sleep onset, less sleep disruption and longer sleep duration. Twelve children with autism and learning difficulties (2 girls and 10 boys aged between 12 years 2 months to 15 years 7 months) in a residential school participated in a within subjects repeated measures design: 3 nights when the children were given aromatherapy massage with lavender oil were compared with 14 nights when it was not given. The children were checked every 30 min throughout the night to determine the time taken for the children to settle to sleep, the number of awakenings and the sleep duration. One boy's data were not analyzed owing to lengthy absence. Repeated measures analysis revealed no differences in any of the sleep measures between the nights when the children were given aromatherapy massage and nights when the children were not given aromatherapy massage. The results suggest that the use of aromatherapy massage with lavender oil has no beneficial effect on the sleep patterns of children with autism attending a residential school. It is possible that there are greater effects in the home environment or with longer-term interventions.

Keywords: Aromatherapy, massage, autism, sleep, children

What is the Evidence for Aromatherapy?

A recent review of the evidence for sensory stimulation in dementia care suggests that aromatherapy with lemon balm or lavender oil decreases agitation in patients with dementia (1). In other populations there are anecdotal reports of the effectiveness of aromatherapy in calming people with autistic spectrum disorders (2) and helping people sleep (3) and relax (4), although a systematic review of the field found little satisfactory evidence for the claims (5). Nevertheless, one of the review authors claimed that there was good evidence for a relaxing effect (6).

The situation is complicated by the fact that aromatherapy is often delivered as a massage, and research studies have not identified clearly which is the active ingredient (7,8). Trials of massage interventions alone have clearly established beneficial effects in chronic pain and situations where muscle relaxation is required (9). In an experimental study published last year, Kuriyama and co-workers were unable to identify psychological effects of aroma over that of the massage alone, but did find physiological effects of aromatic oils over and above that of the carrier oil massage (9). In this investigation we sought to demonstrate the effects of an aromatherapy massage.

How could Aromatherapy Massage help Children with Autism?

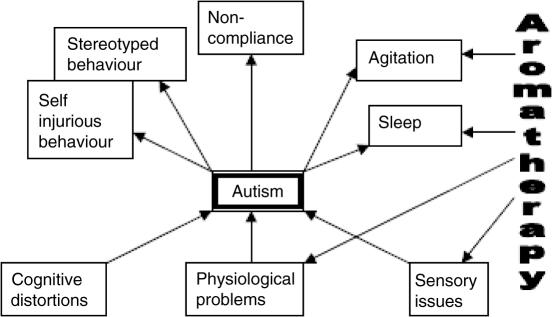

Children with autism have problems establishing a regular diurnal pattern and in remaining asleep through the night (11–13). Some of these difficulties may be owing to over arousal or agitation. Given the effects of aromatherapy massage in dementia and the wider claims of the effects of aromatherapy on sleep and arousal, we sought to examine whether aromatherapy massage enabled an improved sleep pattern in children with autism. During waking hours the behavior of children with autism is characterized by repetitive activities such as stereotyped behavior, which are thought to be the result of non-optimal levels (over and under arousal) of arousal (Fig. 1). The putative mode of action of aromatherapy would be that it enabled an arousal level closer to the optimal, and hence, made sleep both easier to achieve and to maintain. The aims of the study were therefore to examine whether aromatherapy delivered through massage resulted in faster sleep onset, longer sleep durations or fewer sleep interruptions.

Figure 1.

Simplified diagram to show how aromatherapy might act on the problems presented by people with autism. Aromatherapy can act both at the physiological/sensory level and at the level of the behavior problems themselves.

Methods

Participants

All 12 children (2 girls and 10 boys) aged between 12 years 2 months to 15 years 7 months (mean age 14 years 1 month) from one unit of a residential school for children with autism were selected as participants for a trial of aromatherapy. The school checks diagnoses of autism against DSM-IV criteria before the children are admitted. One boy had a diagnosis of Down's syndrome in addition to the diagnosis of autism. One girl was on carbamazepine and topiramate for control of her epilepsy and one of the boys was taking risperidone for control of behavior. All the children had severe learning difficulties and exhibited multiple repetitive behaviors. No children in the unit were excluded from entry to the trial, and the medication taken by the children did not change during the trial.

All the children lived in one residential unit of the school from Sunday to Thursday night inclusive. Only three of the children remained at the school for any of the Friday and Saturday nights during the study. Owing to these small numbers it has not been possible to estimate the effect of remaining for the weekend. Each child slept in a separate bedroom. Although 12 children were considered as participants for the trial, one became ill before the trial and remained at home for 10 of the possible 17 nights. His data has therefore been excluded from the analysis.

Design

A within subjects design was used. Aromatherapy massage was administered on Thursday nights. The period of the study was 24 days, beginning on the first night of the term and finishing after three administrations of aromatherapy. The first night of the study was a Tuesday night, and aromatherapy was provided on the second, third and fourth Thursday nights. This corresponds to an ABABAB design in which the A refers to nights when no aromatherapy was provided, and B refers to those nights when aromatherapy was provided. Nights without aromatherapy can be regarded as baseline nights. The design does carry with it the risk of improvements in sleep over time (a shifting baseline) if the effects of aromatherapy are cumulative.

Procedure

An experienced and trained aromatherapist delivered the aromatherapy as a foot and leg massage using 2% lavender oil in grapeseed oil on three separate evenings during the study period at the school. The timing of each child's aromatherapy was variable owing to other activities undertaken by the child, but was always in the last 2 h before going to bed. All the children were free to leave the aromatherapy sessions, although none did so. In order to accustom the children to aromatherapy massage, it had been used as a leisure activity at various times during the school day in the previous term. This ceased once the trial started. Thus, the intervention was not anxiety provoking for them.

Measures

Sleep onset, sleep duration and wakings from sleep are routinely recorded by waking night staff who checks each child every 30 min throughout the night from 9 p.m. to 6 a.m. Sleep onset time is the time at which the children were first recorded as being asleep. Sleep duration was calculated as the difference between the time the children were first recorded as being asleep and the time the children woke up minus the time periods the children were awake. The number of wakings from sleep was identified from the sleep records. Consecutive records of being awake were counted as a single waking.

Results

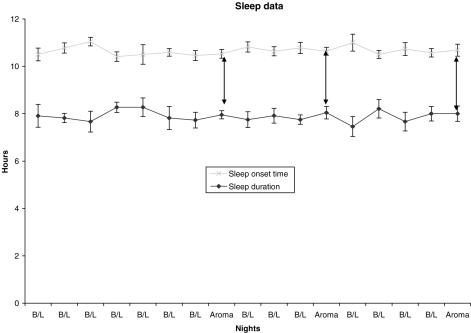

Complete data were available for 11 children. The analyses reported below are for Sunday through Thursday nights of 3 weeks. Data from 17 nights of a possible 24 nights were examined, of which 3 nights included aromatherapy massage as part of the evening schedule. From the 24 possible nights, 3 Fridays and Saturdays were excluded because only 3 children stayed for those nights; a further one night was excluded from analysis because 2 children had been at home on that night (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Mean time first recorded as asleep and mean duration of sleep recorded on nights analyzed. The double headed arrows indicate nights when aromatherapy was administered.

There was little variability in the average time the children fell asleep (Fig. 2). The children fell asleep on average between 10:30 p.m. and 11:15 p.m. A repeated measures analysis of variance comparing nights with and without aromatherapy revealed that there was no night with a statistically significant different sleep onset time (Greenhouse–Geisser corrected F = 1.27; df = 4.15, 41.5; P = 0.30). There was however a significant participant effect suggesting that there were systematic differences in the times at which individual children fell asleep (F = 59.83; df = 1, 10; P < 0.001; meansleep onset time range 9:30 p.m. and 11:40 p.m. Table 1).

Table 1.

Sleep data for individuals whose sleep was analyzed in the study (sleep duration and sleep onset in hours–p.m.)

| Participant | Mean (SE) sleep onset time | Mean (SE) sleep duration |

|---|---|---|

| A | 10:41 (0:06) | 7:19 (0:12) |

| B | 10:57 (0:19) | 7:19 (0:19) |

| C | 11:21 (0:09) | 7:28 (0:10) |

| D | 11:41 (0:08) | 6:51 (0:19) |

| E | 10:17 (0:04) | 8:44 (0:05) |

| F | 10:58 (0:06) | 8:05 (0:06) |

| G | 10:21 (0:05) | 7:09 (0:15) |

| H | 10:46 (0:14) | 8:17 (0:14) |

| I | 9:30 (0:06) | 7:55 (0:26) |

| J | 10:28 (0:06) | 8:35 (0:07) |

| K | 10:13 (0:07) | 8:53 (0:08) |

In total only 22 sleep interruptions were recorded. Seven of the children slept through all the nights without any interruptions. Of the four remaining children, there were between 0.11 and 0.5 interruptions per night (i.e. between one awakening every nine nights and one every other night). There were no significant differences between the nights with and without aromatherapy (Friedman test χ2 = 20.19; df = 16; P = 0.21).

The length of time the children were asleep was also subject to a repeated measures analysis of variance which showed that there was no significant difference between the nights with and without aromatherapy (F = 0.59; df = 16, 160; P = 0.89). The children slept on average between 7.25.and 8.25 h per night (Fig. 2). There was however a statistically significant child effect suggesting that different children had significantly different sleep durations (F = 1411.4; df = 1, 10; P < 0.001; Table 1). The average number of hours slept per child ranged between 6.85 and 8.88 h.

Discussion

What did we Learn?

The results show that there were no statistically significant differences in the time the children went to sleep, the number of times they woke in the night and the length of time the children slept that could be ascribed to the aromatherapy massage. It was well tolerated by the children. Each child's sleep pattern seemed to be stable although there were marked inter-individual differences in both the duration of sleep and the sleep onset time. In summary, where children with autism and severe learning difficulties sleep well, aromatherapy massage does not appear to offer benefits for sleep patterns.

Limitations of the Study

A better study would have allowed for evaluation of the introduction of the intervention. Our results also suggest that the sample size may have been too small to detect a significant effect. Power calculations suggest that for an increase in sleep duration of 30 min, a sample of 160 children would need to be recruited. Alternatively, aromatherapy would need to produce an increase in sleep duration of about 1 h 6 min to reach a power of 0.80 at the 0.05 significance level. Our estimates of effect sizes may however have been skewed by the relatively good sleep pattern the children showed. While it is possible that a more sensitive measure of sleep would enable smaller effects on sleep to be detected, the inter- and intra-individual variability is so great that this seems unlikely.

Does this Study Agree with Others on Aromatherapy Massage?

This study offers evidence on the effects of aromatherapy massage on sleep patterns in children with comorbid learning disabilities and autism. To our knowledge this article represents the first attempt to evaluate the effects of aromatherapy massage on the sleep of people with autistic spectrum disorders. It differs from previous studies by virtue of considering sleep. A previous study with adults with learning disabilities similarly noted little change in communication skills, as a result of the use of aromatherapy massage (14). In contrast, the literature on agitation in the elderly suggests that there are benefits of the combined aromatherapy massage procedure, although these may not extend to pure aromatherapy [i.e. administration of the oil without massage or skin contact (8)].

These results are concordant with the systematic review of aromatherapy interventions reported by Cooke and Ernst (5). They concluded that the effects on anxiety were small and transient, but cautioned that the trials were conducted with participants for whom conventional anxiolytic treatment was not warranted. Similarly, the sleep patterns of the participants in this study did not warrant the use of medication. Indeed, the sleep pattern of the children is better than that of children in the community studied using actigraphic measures (13). The children in this study went to sleep at about the same time as the sleepless group in Wiggs and Stores (13), but showed rather less waking in the night. It might be better, therefore, to research aromatherapy massage in community samples where sleep problems are more prevalent.

What are Future Concerns for Analyses of Aromatherapy?

The fact that the children tolerated the aromatherapy massage suggests that further investigations of aromatherapy massage could be undertaken with this group. Future studies will have to take into account general concerns about the most appropriate design for a trial of aromatherapy massage. Any treatment that involves bodily contact cannot easily be subject to a double blind trial because the recipient will inevitably be aware that they are being touched. The materials used also leave traces on the skin of the recipient, and the aromatic constituent is easily detected. In order to ensure adequate blinding of the assessors, video or automated data gathering methods (e.g. actimeters, which are small devices the size of a wrist watch) would be useful. Alternatively, researchers might wish to consider the possibility of separating the aromatherapy and massage constituents of this intervention, since lavender oil mist has already been shown to have beneficial effects on agitation in the elderly (8) and there is some research showing better immune responses when aromatic essential oils are added to massage procedures (9). There may be a priori reasons for considering that some types of touch or aroma are non-therapeutic for this population, which would enable a comparative trial of different types of touch or aroma. Some consideration should also be given to the possibility that this population might choose to have aromatherapy massage because it is a pleasant sensation regardless of its effects on sleep, behavior or learning. Further trials should therefore consider the implications for the quality of life of the participants, by measuring behavioral disturbances, learning or quality of life in this population.

Finally, consideration should be given to the optimum duration of the intervention. The use of an ABABAB design requires both that aromatherapy has a rapid mode of action and that it does not continue to have effects for more than a few hours after it was administered. Support for this assertion comes from studies on sleep in the elderly (15) and joint attention in children with autism (16). However, one study has reported effects lasting several days for anxiety in children with autism (16). A further risk is that the effect of aromatherapy is cumulative, and becomes evident only after several administrations. As Fig. 2 shows that there appeared to be no significant gradient as would occur if a shifting baseline was involved. A much longer series of repeated administrations might enable a more thorough investigation of these effects.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to all the children and staff at Priors Court School, who gave of their time to make this project successful.

REFERENCES

- 1.Burns A, Byrne J, Ballard C, Holmes C. Sensory stimulation in dementia: an effective option for managing behavioural problems. Br Med J. 2002;325:1312–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7376.1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ellwood J. Aromatherapy and autism. Available at: http://www.aromacaring.co.uk/aromatherapy_and_autism.htm (last accessed 1 July 2005)

- 3.McCutcheon L. What's that I smell? The claims of aromatherapy. Skeptical Inquirer May 1996. Available at: http://www.csicorp.org/si/9605/aroma.html (last accessed 1 July 2005)

- 4.Maddocks-Jennings W, Wilkinson JM. Aromatherapy practice in nursing: literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2004;48:93–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cooke B, Ernst E. Aromatherapy: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2000;50:493–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ernst E. The role of complementary and alternative medicine. Br Med J. 2000;321:1133–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7269.1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holmes C, Hopkins V, Hensford C, MacLaughlin V, Wilkinson D, Rosenvinge H. Lavender oil as a treatment for agitated behaviour in severe dementia: a placebo controlled study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;17:305–8. doi: 10.1002/gps.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Snow AL, Hovanec L, Brandt J. A controlled trial of aromatherapy for agitation in nursing home patients with dementia. J Altern Complement Med. 2004;10:431–7. doi: 10.1089/1075553041323696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fellows D, Barnes K, Wilkinson S. Aromatherapy and massage for symptom relief in patients with cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002287.pub2. CD002287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuriyama H, Watanabe S, Nakaya T, Shigemori I, Kita M, Yoshida N, et al. Immunological and psychological benefits of aromatherapy massage. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2005;2:179–84. doi: 10.1093/ecam/neh087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diomedi M, Curatolo P, Scalise A, Placidi F, Caretto F, Gigli GL. Sleep abnormalities in mentally retarded autistic subjects: Down's syndrome with mental retardation and normal subjects. Brain Dev. 1999;21:548–53. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(99)00077-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patzold LM, Richdale AL, Tonge BJ. An investigation into sleep characteristics of children with autism and Asperger's Disorder. J Paediatr Child Health. 1998;34:528–33. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1754.1998.00291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wiggs L, Stores G. Sleep patterns and sleep disorders in children with autistic spectrum disorders: insights using parent report and actigraphy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2004;46:372–80. doi: 10.1017/s0012162204000611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lindsay WR, Black E, Broxholme S, Pitcaithly D, Hornsby N. Effects of four therapy procedures on communication in people with profound intellectual disabilities. J Appl Res in Intellect Disabil. 2001;14:110–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Connell FEA, Tan G, Gupta I, Gompertz P, Bennett GCJ, Herzberg JL. Can aromatherapy promote sleep in elderly hospitalized patients. J Can Geriatr Soc. 2001;4:191–5. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Solomons S. Using aromatherapy massage to increase shared attention behaviours in children with autistic spectrum disorders and severe learning difficulties. Br J Spec Educ. 2005;32:137. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilkinson S, Aldridge J, Salmon I, Cain E, Wilson B. An evaluation of aromatherapy massage in palliative care. Palliat Med. 1999;13:409–17. doi: 10.1191/026921699678148345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]