Abstract

The expansion of women in the military is reshaping the veteran population, with women now constituting the fastest growing segment of eligible VA health care users. In recognition of the changing demographics and special health care needs of women, the VA Office of Research & Development recently sponsored the first national VA Women's Health Research Agenda-setting conference to map research priorities to the needs of women veterans and position VA as a national leader in Women's Health Research. This paper summarizes the process and outcomes of this effort, outlining VA's research priorities for biomedical, clinical, rehabilitation, and health services research.

Keywords: women's health, research and development, research priorities, veterans, health care quality, access and evaluation

Consistent with strategic planning processes led by the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) to ensure that increasingly scarce resources are invested in areas of highest priority, the VA Office of Research & Development (ORD) has initiated a process of analyzing and evaluating its research portfolio. In recognition of the changing demographics and the special health care needs of women, the ORD has assigned research on women's health a high priority and it is one of the first topics to undergo such review. Over the last decade, the VA has built an increasingly productive portfolio of research in all 4 of its Research and Development Services (Biomedical Laboratory, Clinical Science, Rehabilitation, and Health Services), with significant potential to improve the health of women veterans. The purpose of this paper is to summarize the VA's current research efforts related to women's health, describe the agenda-setting process, and present the resulting national VA Women's Health Research Agenda.

VA WOMEN'S HEALTH RESEARCH AGENDA-SETTING PROCESS

In early 2004, the VA Office of Research & Development tasked VA HSR&D Service with oversight of the development of the first national VA Women's Health Research Agenda that would span all 4 Research and Development Services. Representatives from across the country with demonstrated track records in VA Women's Health Research were invited to join a national planning group, create an agenda-setting plan, and enact it. The Planning Group developed a 4-step action plan, designed to meet the health care needs of women veterans and position VA as a national leader in Women's Health Research (Table 1).1

Table 1.

Four-Step Action Plan Toward a VA Women's Health Research Agenda

| Action Plan | Approach | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Step #1: Critically appraise the VA research portfolio | Obtain and review history of funding among VA researchers | Conducted portfolio analysis of VA women's health research funding |

| Analyze data by types of funding (e.g., VA, other federal, private, foundation) | ||

| Analyze data by research area (e.g., aging, mental health, reproductive health) | Established methods for ongoing monitoring of VA women's health research portfolio | |

| Step #2: Obtain systematic information about the health and health care of women veterans to provide an evidence base for the research agenda | Conduct gender-specific analyses of an array of VA secondary data | Obtained analyses from 15+ centers in support of agenda-setting process |

| Conduct a systematic women veterans' literature review | Completed a systematic literature review | |

| Developed a web-based bibliography | ||

| Step #3: Based upon gaps between the current VA research portfolio (Step #1) and the assessment of the evidence base (Step #2), identify strategic priorities for the VA women's health research agenda | Adapt priority-setting strategies used by other agencies (e.g., NIH Office of Research on Women's Health, AHRQ) | Created a compendium of women's health research initiatives |

| Review VA strategic plans (e.g., Women Veterans Health Program, Advisory Committee for Women Veterans) | Conducted the first national VA women's health agenda-setting conference (Nov 2004) | |

| Conduct gap analysis, priority-setting, and consensus development in an agenda-setting conference | Disseminated web-based products from all steps | |

| Step #4: Foster the conduct of VA women's health research | Build research capacity through improved collaboration, networking, and mentoring | Created a VA women's health research website* |

| Solve methodologic challenges (e.g., small sample sizes) | Created a Listserv for use by VA women's health researchers | |

| Increase awareness and visibility of VA women's health research | Develop web- and cyber-based educational modules on key methodologic issues |

VA women's health research website (http://www.va.gov/resdev/programs/womens_health/) contains background information on women veterans, summaries, and online presentations from the VA women's health research conference, and other useful announcements and links.

Appraisal of the VA's Research Portfolio

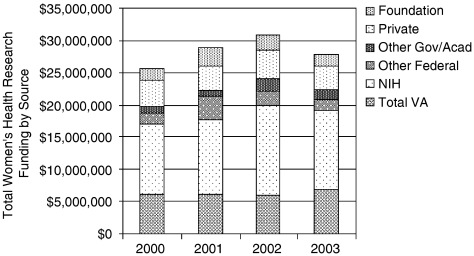

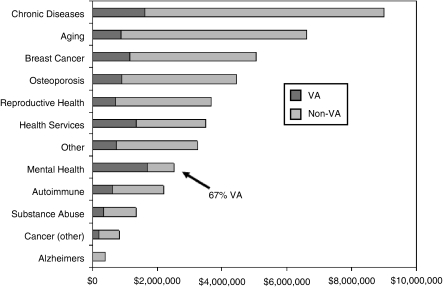

As of fiscal year 2003, funding of Women's Health Research to VA-based investigators totaled $27.9 million for 273 studies (National Institutes of Health [NIH], foundation, private, other federal and government, and VA funding combined), constituting 2.6% of all funding reported by VA investigators ($1.08 billion). Although the absolute amount of funding increased from 2000 to 2003, there was a decline in the overall proportion of Women's Health Research funding in relation to total funding (Table 2). The majority of funding for Women's Health Research among VA investigators was from NIH sources (Fig. 1). The VA-funded portion, $6.9 million, amounted to about 25% of each dollar spent on Women's Health Research in 2003, or 1.9% of the $366.9 million total VA research funding. VA increased its investment by almost $1 million in Women's Health Research between 2002 and 2003, while total funding for Women's Health Research by all funding sources and total VA funding declined in the same period (Table 2). The categories with the highest funding included chronic diseases, aging, breast cancer, and osteoporosis (Fig. 2). VA's research investment was highest in mental health, where it exceeded non-VA funding (67% of total). Little Women's Health Research has been funded on substance abuse, cancers other than breast, or Alzheimer's disease.

Table 2.

Women's Health Research Funding Portfolio Among VA Investigators

| Year | Total Funding | Women's Health Funding | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Women's Health Research as percent of total research funding (all funders) | |||

| 2000 | $821,032,693 | $25,680,259 | 3.1 |

| 2001 | $928,540,420 | $28,896,057 | 3.1 |

| 2002 | $1,010,795,393 | $30,788,988 | 3.0 |

| 2003 | $1,079,979,025 | $27,933,800 | 2.6 |

| Women's Health Research as percent of total research funding (VA only) | |||

| 2000 | $313,967,151 | $6,074,963 | 1.9 |

| 2001 | $333,564,215 | $6,097,515 | 1.8 |

| 2002 | $370,290,877 | $6,018,916 | 1.6 |

| 2003 | $366,908,456 | $6,931,449 | 1.9 |

| Year | Total Number of Projects | Number of New Projects | Number of Investigators |

| Numbers of Women's Health Research total projects, new projects and investigators (all funders) | |||

| 2000 | 309 | 117 | 212 |

| 2001 | 319 | 109 | 213 |

| 2002 | 301 | 91 | 204 |

| 2003 | 273 | 65 | 192 |

Source: U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Research and Development (ORD), 2004.

FIGURE 1.

Total women's health research funding by source.

FIGURE 2.

Total fiscal year 2003 women's health research funding by disease area and funding source (VA and non-VA).

We also examined VA-funded Women's Health Research. Some of the VA's hallmark studies include the National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study, which included women veterans2–6; studies of the impact of military environmental exposure on reproductive outcomes among U.S. women Vietnam veterans7, 8; the first national assessment of the health status and effects of military service on self-reported health among women veterans who use VA ambulatory care9–13; analyses of the large survey of veterans, which included over 30,000 women veterans14; and an evaluation of the surgical risks and outcomes of women treated in VA hospitals.15–17 Table 3 presents highlights of recent VA Women's Health Research.

Table 3.

Highlights of Recent VA Women's Health Research*

| VA Research Service | Highlights of Recent Research |

|---|---|

| VA Biomedical Laboratory Research and Development | Identification of a new synthetic estrogen-like compound that reverses bone loss in mice without the reproductive side effects of conventional hormone replacement therapy |

| Prevention of a disease resembling multiple sclerosis in female mice through a combined therapy of estrogen and a T-cell receptor vaccine | |

| Association of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) with prolactin, a pituitary hormone that increases during pregnancy, leading to bromocriptine, a prolactin suppressant, as a potential treatment for SLE | |

| VA Clinical Science Research and Development (including the Cooperative Studies Program) | Randomized clinical trial of treatment for PTSD in women veterans (jointly funded by Department of Defense): |

| First multi-site VA clinical trial focused only on women | |

| 12 sites, 284 women veterans and active duty military enrolled | |

| Evaluating efficacy of a type of cognitive behavioral therapy for treating PTSD | |

| VA Rehabilitation Research and Development | Animal model of stress urinary incontinence being developed and tested to develop new strategies for treatment and prevention |

| Estrogen treatment at time of initial injury (rather than prior to or after injury) may facilitate functional recovery and regeneration of injured nerves | |

| A functional virtual reality model of the pelvic floor and organs being developed for education, simulation of surgical outcomes, and planning complex surgical procedures | |

| VA Health Services Research and Development | Evaluation of the prevalence and risks of problem drinking among women veterans |

| Influence of PTSD, depression, and military sexual assault on physical health/function | |

| Comparison of patient satisfaction in different VA women's health care models | |

| Assessment tool and intervention to enhance gender-aware VA health care | |

| Identification of women veterans' ambulatory care use, barriers, and influences |

All VA-funded studies are searchable online at http://www1.va.gov/resdev/.

Establishing the Evidence Base for Agenda Development

One of the goals of the VA research agenda-setting process was to build a systematic evidence base that supported the alignment of VA research priorities with the health-related needs of women veterans. We used 2 strategies to accomplish this goal, which included (1) capitalizing on VA's extensive clinical and administrative data repositories to conduct gender-specific analyses18 and (2) conducting a systematic literature review and synthesis through a partnership with the Southern California Evidence-Based Practice Center.

Secondary Analyses of VA Data

Our objective was to identify high-prevalence, high-cost, high-impact conditions among women veterans, as well as conditions with disproportionate burden among women (e.g., obesity, incontinence, osteoporosis) or with distinct clinical presentations in women (e.g., coronary artery disease). We began by listing the available data sources for conducting queries by gender (Table 4). Over 15 research centers responded to our requests for gender-specific analyses of existing data, demonstrating both the capacity and commitment to furthering the VA Women's Health Research Agenda. While the results of these secondary analyses are too numerous to cover here, subsequent priority-setting was informed by the most prevalent diagnoses (e.g., post-traumatic stress disorder [PTSD], arthritis, chronic low back pain, hypertension, chronic lung disease, depression), most commonly prescribed drugs (e.g., simvastatin, levothyroxine, lisinopril), and gender comparisons in patient satisfaction, quality, and costs of care. This process highlighted that these data sources had been underutilized in the past, demonstrating substantial opportunities for additional analyses.

Table 4.

Selected Data Sources Available for the Assessment of Women Veterans' Health and Health Care

| Data Source | Description |

|---|---|

| National Survey of Veterans (NSV)* | Approximately decennial survey (2001, 1992, etc.) conducted among random digit dial (RDD) veteran samples augmented by VA administrative lists of VA users to provide national estimates for veterans overall and for key subgroups (n=20,048, 2001 NSV) |

| Contains sociodemographic characteristics, period of service, combat exposure, insurance coverage, VA and non-VA health care utilization, health status, functional limitations, health conditions, eligibility, and more | |

| Survey of Healthcare Experiences of Patients (SHEPs)† | Adapted from earlier annual patient satisfaction surveys launched in the mid 1990s Random samples of veteran users of VA services |

| Contains data on health status, quality of life, health care utilization, satisfaction, etc. | |

| External Peer Review Program (EPRP)† | Part of VHA's performance measurement system composed of externally abstracted medical record data from randomly sampled records of VA users at each VA facility |

| Patient- and facility-level data on chronic disease quality (e.g., foot sensation exams among diabetics) and preventive practice (e.g., flu shots) | |

| Large Survey of Veterans† | National survey sample of veteran users of VA health care (includes about 33,000 women) (1999) |

| Includes health status, conditions, satisfaction, utilization, quality of life, etc. | |

| VHA Medical SAS Datasets (utitlization data)‡ | National administrative data for VA-provided health care used primarily by veterans, but also by some non-veterans (e.g., employees) (housed in Austin Automation Center) |

| Includes medical inpatient data (acute, extended, observation, non-VA) organized by stay, bedsection, procedures and surgeries; outpatient data (visits and events); long-term care data (representing an array of services in VA nursing homes, community nursing homes, domiciliaries, home-based primary care, home health care, etc.) | |

| VA-Medicare Data‡ | Linked VA and Medicare health care utilization data, including Part A and B claims, and patient and provider information files |

| Pharmacy Benefits Management (PBM) Program‡ | Prescription information for all VA patients who obtain their prescriptions within the VA system (available from FY 1999 through present) |

| Useful for studying prescribing habits, drug utilization trends, and pharmacoeconomics | |

| Decision Support System (cost data)‡, § | Contains data on the cost of care of every individual patient care encounter in VA Starts from fiscal year 1998 in national extracts organized by inpatient discharges, inpatient treating specialty files, and outpatient files |

| National Survey Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP)∥ | National, validated, outcomes-based, risk-adjusted program for measurement and enhancement of surgical care (begun in 1991) |

| Currently incorporates all VAMCs and 14 private hospitals with extensive surgical data | |

| Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI) Centers¶ | National initiative to translate research into practice organized around specific conditions (diabetes, mental health, ischemic heart disease, spinal cord injury, HIV/AIDS, colorectal cancer, stroke, substance abuse) |

| Selected QUERIs have developed patient registries allowing for disease-based analyses | |

| Women Veterans Health Program (WVHP) Evaluation# | Organizational data at the VISN, VA medical center, and practice levels, with multiple perspectives available at the practice-level |

| Includes structure, staffing, leadership, authority, resource sufficiency, etc. |

Full survey final report and national frequencies online at http://www.va.gov/vetdata/SurveyResults/final.htm.

Available through formal Data Use Agreements with the VA Office of Quality and Performance (OQP).

VA Information Resource and Education Center (VIREC) (http://www.virec.research.med.va.gov).

VA Health Economics Resource Center (HERC) (http://www.herc.research.med.va.gov).

VA National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (http://www.nsqip.org).

VA Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI) (http://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/queri/) (links to individual QUERI Centers also available through this web address).

Women Veterans Health Program (WVHP) Office (http://www1/va/gov/wvhp).

Systematic Literature Review

The Office of Research & Development commissioned the conduct of a systematic literature review to develop a synthesis of what is known about women veterans' research.19 The resulting review pointed to gaps in knowledge about specific health risks among women veterans, quality of care, and treatments for PTSD and other conditions of high prevalence among women veterans. A full bibliography is available on request.

Achieving Consensus on Research Priorities

Several governmental agencies and private organizations are committed to the advancement of Women's Health Research both within and outside the VA. To assure that our approach and priorities were set within the context of the substantial work accomplished by others, the Planning Group adapted themes and strategies used by other agencies and organizations to develop VA's research priorities in combination with empirical evidence regarding patterns of disease burden among women veterans. These included, for example, the NIH Office of Research on Women's Health,20 the Defense Women's Health Research Program,21 the TriService Nursing Research Program,22 and the Society for Research on Women's Health.23 We also reviewed strategic planning and advisory documents from the Women Veterans Health Program,24 and obtained research recommendations from the Advisory Committee for Women Veterans,25 and the Defense Advisory Committee on Women in the Services26 through the Center for Women Veterans.

We combined results from the work of these other groups, our own appraisal of the gaps between the current VA research portfolio (Step #1), and the assessment of the evidence base (Step #2) and presented them as a foundation for an agenda-setting conference held in November 2004. Over 50 VA and non-VA Women's Health Researchers were invited to participate in the consensus development effort to synthesize information from overviews presented by VA leaders, followed by a series of presentations summarizing advance work completed by planning group members.27 Participants were subsequently divided into 5 workgroups (biomedical, clinical, rehabilitation, health services, and infrastructure), each with a planning group moderator to help them cull the presented information and generate research priorities and solicitation topics. Workgroups then reconvened as a whole, presented their recommendations, and received expert input from a panel of senior VA leaders in operations and research, and Women's Health Research experts at the NIH Office of Research on Women's Health28–29 and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ).30

VA'S WOMEN'S HEALTH RESEARCH AGENDA

Biomedical Laboratory Research Priorities

The Biomedical Workgroup established research on sex-based influences on prevention, induction, and progression of diseases relevant to women veterans as their overarching focus. Based on current evidence of the prevalence of conditions among women veterans, the Biomedical research priorities focused on (1) mental health (especially PTSD, stress, addiction, sexual trauma, and depression), (2) military occupational hazards (focused on injury and rehabilitation, wound healing, tissue remodeling, vaccine development, and biological and chemical exposures), (3) chronic diseases (with emphasis on diabetes, infections, autoimmunity, osteoporosis, arthritis, and chronic pain), (4) cancer (focused on etiology and response to treatment for exposure-related cancers), and (5) reproductive health (including fertility, contraception, and menopausal issues).

Because many of these priorities overlap with programmatic themes of the NIH Office of Research on Women's Health, VA researchers will need to remain apprised of advances and opportunities that cross agency lines. Nonetheless, VA has unique strengths that will facilitate the advancement of novel biomedical research.

Clinical Science Research Priorities

The Clinical Science Workgroup focused on the relative paucity of reliable epidemiologic data on women veterans, spanning from risks and exposures before entry into the military, through military experience and exposures, to status after military discharge regardless of their ultimate choice of care provider (VA or not VA). While the Department of Defense (DoD) has established inception cohorts of female veterans, access to these data for the purposes of linking past exposures forward through their veteran years has been problematic. Moreover, few VA clinical studies have been conducted among women veterans, hindered mainly by the small numbers of women at individual facilities. Priority recommendations included creating data use agreements that facilitate VA researchers' access to DoD databases on military women. Barring that, creation of a prospective cohort of women upon discharge from the military (i.e., when they become veterans) should be pursued to build the necessary foundation for future VA research.

In the interim, the Clinical Sciences Workgroup identified special conditions and populations on whom VA clinical research should be focused, including (1) pregnancy and fertility issues, (2) returning military and reservists, (3) long-term care, (4) substance abuse and mental health, (5) homelessness, (6) PTSD and military sexual trauma, and (7) recent amputees.

Rehabilitation Research Priorities

The VA's Rehabilitation Research and Development (RR&D) Service spans biomedical, clinical, and health services research in service of maximizing function and quality of life (including vocational outcomes), preventing and treating secondary complications, and addressing psychosocial issues associated with disability and recovery. The Rehabilitation Workgroup established 6 priority conditions/diseases, focused on the rehabilitative aspects associated with (1) arthritis, (2) chronic pain, (3) obesity, (4) osteoporosis/fall-related injuries, (5) amputation (specifically, socket-fit technology), and (6) reproductive challenges for disabled women veterans. While some of these priorities are shared by NIH, VA's unique contributions include prosthetics (e.g., menstrual cycle/limb volume variability and socket-fit for amputees) and rehabilitation engineering (e.g., assistive technologies among women with disabilities; gender-specific technologies for urinary incontinence). Because of VA's investment in centralized administrative and clinical databases, VA researchers are also well-positioned to explore gender differences in chronic pain and obesity in relation to rehabilitation outcomes. Given the rehabilitation demands of the injuries incurred by women veterans who have served in Iraq and Afghanistan, opportunities for using merged DoD-VA data in service of research capable of improving their quality of care are being missed. They also recommended joint agency requests-for-applications (RFAs), for example, between the VA and the National Institute of Disability and Rehabilitation Research or within-VA initiatives, for example, between RR&D and the VA's Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI), leveraging resources and expertise to improve women veterans' health and health care related to disabling stages of QUERI conditions (e.g., stroke).

Health Services Research Priorities

The Health Services Workgroup focused on development of 2 targeted RFAs, 1 on evaluation of models for delivery of women veterans' health care, and another fostering needs assessment projects. The core goals for delivery model studies focused on the need to measure the quality associated with different care models serving women veterans, including, for example, evaluations by setting (e.g., large VA medical centers vs. small community-based outpatient clinics); by type of provider (e.g., among fee-basis or contract providers, same-gender providers) and to evaluate the quality, costs, access, and continuity tradeoffs women veterans face in different care settings and for different health conditions (e.g., mental health, specialty care, gender-specific services). Benchmarking VA-based access and quality to services outside the VA is also a priority to ensure equitable care provision. The Workgroup called for needs assessment for high-impact conditions, including psychiatric/emotional disorders and military-specific exposures, assessments of women veterans' needs and preferences for health services and their care environment, gender-specific barriers to access (including issues related to service connection), and better epidemiologic data on their disease burden and utilization patterns. Selected on the basis of their likely impact on health-related quality of life, high-priority conditions included the following:

Psychiatric/emotional health

Reproductive health/infertility/pregnancy

Military-specific exposures

Bone and musculoskeletal diseases

Chronic pain

Behavioral health (e.g., drugs, alcohol, tobacco, stress-related)

Obesity/metabolic syndrome/diabetes

Thyroid disorders

Urinary incontinence

Menstrual disorders/menopausal symptoms

Oral health

Eye/vision problems

Building an Infrastructure for Fostering the Conduct of VA Women's Health Research

At all stages, the need to build an effective infrastructure for fostering the conduct of VA Women's Health Research was deemed central to the success of the resulting agenda. In particular, while several pioneering VA researchers interested in exploring women veterans' health research have made significant inroads in contributing to our knowledge base over the past decade, anecdotal stories about perceived barriers to conducting, and publishing research about women veterans challenged us to ascertain their prevalence.

Conference participants were therefore asked to complete a brief barriers survey before the conference to permit time for analysis and feedback (85% response rate, n=28). VA-based Women's Health Research was roughly split between the study of nonveteran women (61%) and veteran women who used the VA (57%). (Note: Conferees could report more than 1 type of research, resulting in sums over 100%.) Over a quarter (28%) conducted research involving women veterans who do not use VA health care; only 18% had conducted research on women in the military. Only 18% had done research on biomedical samples taken from women and 14% on animal studies related to gender issues, although these figures also reflect the distribution of survey respondents (18% were biomedical researchers).

The top 5 perceived barriers to conducting VA Women's Health Research were cited as: (1) the lack of a network of VA facilities to recruit women veterans for research studies, (2) difficulty in identifying women veterans who do not use the VA, (3) lack of coordination with other agencies (e.g., DoD), (4) lack of availability of needed variables in centralized databases, and (5) low numbers of women veterans overall. These results were reported to all conference participants and provided to the Infrastructure Workgroup for discussion and suggestions for resolution.

Details for resolving each identified barrier are listed in Table 5. Central to building the needed infrastructure is the development of VA practice-based research networks akin to those cultivated by AHRQ for primary care research, but among sites with larger caseloads of women veterans to facilitate recruitment efforts. Considerable education of the field (i.e., reviewers, investigators, non-VA research partners) is also needed to publicize the opportunities and demand for more VA Women's Health Research, as well as solutions to some of the methodologic challenges, such as the Institute of Medicine's brief on small sample size methods and their role in advancing research. The value of and potential role for inter-agency collaborations is substantial, for example, with DoD to conduct longitudinal research that builds on military cohorts, and with the National Center for Health Statistics to integrate veteran status into national surveys, as AHRQ does in the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. Finally, backing the agenda with new funding is key. VA HSR&D Service has already published a new Women's Health solicitation, while planning grants, pilot funds, and administrative supplements to add women (or female specimens) to existing studies were proposed to accelerate and promote greater inclusion of women.

Table 5.

Improving the Infrastructure for Enhancing VA Women's Health Research

| Research Barriers | Strategic Problems | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Small number of women in the VA system | Lack of network or infrastructure to facilitate research | Develop VA practice-based research networks among VA facilities with adequate women veteran samples (e.g., recruit sites with a VA Comprehensive Women's Health Center or other large caseload sites) |

| Inadequate knowledge and familiarity with small-sample study designs and statistics | Improve familiarity and use of VA Cooperative Studies Program (CSP) for multi-site trials (invite CSP staff to present to VA women's health research audiences in different venues) | |

| Lack of reviewer knowledge of small-sample issues | Address skill and knowledge deficits through educational programs (e.g., reviewer training, research briefs to investigators, seminars linked to VA meetings, web- and cyber-education) | |

| Create methodologic briefs for distribution (similar to VA HSR&D Management Briefs) | ||

| Identifying women veterans who do not use the VA | Lack of reliable, valid, updated women veterans registry | Coordinate recruitment and enrollment of recently discharged veterans through the Transitional Assistance Program (TAP) (i.e., advertise VA women's health research) |

| HIPAA restrictions on accessing data enabling research across settings | Develop and maintain an updated women veterans' registry from military discharge forward | |

| Identify non-VA databases that identify veteran status and foster inclusion of veteran status in those without such indicators | ||

| Forge VA-DoD research partnerships enabling VA researchers to build on active duty research and offering DoD researchers opportunities to conduct longitudinal research | ||

| Problems with secondary databases | Lack of coordination with other agencies (including difficulty obtaining non-VA funds to study veterans, inadequate outside understanding of VA relevance) | Forge VA-DoD research partnerships and data sharing agreements to improve VA investigator access |

| Lack of relevant variables in centralized data sources | Develop mechanisms to link VA data to other non-VA databases (model after VA/Medicare data merge) | |

| Lack of knowledge on available data | Incorporate more gender-specific measures in centralized data collection efforts and database composition | |

| Need for information about outside VA use (including contract care) | Increase degree of over-sampling of women veterans in ongoing data collection efforts (e.g., Office of Quality & Performance chart-based or survey data) | |

| Enhance use of gender-specific data by routinely distributing aggregated data by gender | ||

| Distribute information about data sources that may be used for assessment of women veterans' health and health care issues (e.g., Listserv, weblinks from the VA R&D Women's Health Research site to VA datasets or resource centers) | ||

| Perceived barriers to conducting and publishing VA women's health research | Negative attitudes and misperceptions about women veterans' research | Produce regular women veterans' research updates to larger VA research community |

| Pressures on clinician investigators (need for protected time and methodologic supports) | Assess barriers faced by clinician investigators and evaluate options for leveraging time | |

| Reviewers within and outside VA with limited knowledge of women veterans' health issues | Partner clinician investigators with doctorally trained researchers where possible | |

| Competing research investment demands and constrained budgets | Add women's health researchers to VA scientific review committees | |

| Provide all VA research reviewers with training on issues relevant to women veterans' research, including briefings on small sample size research designs, statistics, and analysis (or consider separate review groups with needed expertise) | ||

| Leverage existing research funding by providing access to administrative supplements for studies that will add women or female specimens or animals to do gender comparisons | ||

| Provide planning funds to researchers to determine feasibility and strategies to recruit adequate sample size or specimen quality | ||

| Foster creation of VISN pilot funds for research projects that evaluate women veterans' health and health care |

Building a consortium of researchers committed to women veterans' health research within VA and through university and other partnerships is a crucial next step. The agenda-setting conference was an important first step in this regard, building on existing ties across VA and non-VA organizations and creating new ones. The VA research website has already fostered new collaborations and mentoring relationships, while providing access to a searchable database of VA investigators, funded studies and publications. Access to VA datasets has been enhanced through data use agreements and technical consultation with 1 or more VA resource centers, such as the VA Information Resource and Education Center. While leading VA-funded research still requires a 5/8th VA appointment, non-VA researchers commonly collaborate with VA-based researchers, capitalizing on special expertise and common interests to pursue a broad range of research studies, whereas other agencies (e.g., National Cancer Institute) also fund women veterans' research, providing additional venues for non-VA researchers to directly contribute to this growing field.

CONCLUSIONS

Using a systematic evidence base and consensus development process among stakeholders within and outside the VA, we report on the first national VA Women's Health Research Agenda. While the VA made women's health a research priority in the early 1990s, enabling the development and funding of an important array of studies that spanned the research spectrum from bench-to-bedside, we anticipate that the level of commitment and strategic planning of this agenda-setting effort has the potential to serve as a strong foundation for the next decade of women veterans' health research. The processes used to set research priorities also have important implications for improving research management across diverse programs, particularly in reference to special populations.

To effectively foster the conduct and expansion of Women's Health Research in VA, the consensus was that the VA Office of Research & Development needs to build research capacity, solve methodologic issues that limit participation of women in research, and increase the awareness and visibility of VA Women's Health Research. Building bridges to research partners at agencies with longstanding commitments to advancing women's health and improving gender equity will continue to invigorate the VA research process.31, 32

While the VA mandated inclusion of women in all VA studies in 1983, our assessment of funded research suggests that compliance has been less than optimal but may not be correctable without assistance to researchers to recruit greater numbers of women veterans into their studies. Given fiscal realities of constrained federal budgets at the same time new veterans are entering the system, we offer some innovative solutions to leverage system resources and talents of the VA's many investigators and their partners in other systems.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs' Office of Research & Development (Project # CSF 04-376) and the VA HSR&D Center for the Study of Healthcare Provider Behavior (Project # HFP 94-028) and overseen by the VA Health Services Research & Development (HSR&D) Service. The project was approved by the IRB at the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System. We are indebted to John Demakis, MD, Shirley Meehan, PhD, MBA, Martha Bryan, EdD, and Serena Chu, PhD, in VA HSR&D Service for planning support; Ismelda Canelo, Sam Garcia, Lisa Tarr, Lorena Barrios, Allyson Szabo, and Vera Snyder-Schwartz at the VA Greater Los Angeles HSR&D Center of Excellence for project support; Brigadier General Wilma L. Vaught (USAF, Ret.), former Department of Veterans Affairs' Chief of Staff Nora Egan, Deputy Under Secretary for Health Michael Kussman, MD, and Deputy Under Secretary for Health for Operations and Management Laura Miller, CHE, MBA, for their leadership support; and Rosaly Correa-de-Araujo, MD, PhD, of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and Loretta Finnegan, MD, of the NIH Office of Research on Women's Health, for serving as conference panelists. We would also like to acknowledge the input of all conference participants. This work was partially presented and generated at the National VA Women's Health Research Agenda-Setting Conference held in Arlington, Virginia, November 8–9, 2004. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Voices of Women Veterans (continued)

VA HEALTH CARE EXPERIENCES

“In a real time of need, the VA has by the Grace of God come to my aid. After a 30 year marriage, my husband wanted a divorce - I lost my home and my business - my retirement and all insurance I had. Unbeknownst to me, I was in fact eligible for health care….”

“When I was leaving active duty, I went to a VA counselor who told me that the highest possible disability rating I could get would be 10%, and that was improbable. So for several years, I forgot about the VA. My sister encouraged me to try again, and a DAV rep helped me get a 70% rating. Ever since then, I have been thrilled with the medical care I have received. I have never been made to feel rushed or unimportant.”

“As far as health care through the VA system, I could not have asked for better. The doctors and all other staff are well-trained, knowledgeable, and most of all caring.”

“Prior to finding out about the women's clinic within the VA, I did not use the VA because getting appointments was a hassle.”

“I never knew until the middle 90s that I could get health care at the VA. Two and a half years ago, I re-injured my back and had a lot of trouble getting help at the VA. I was sent to and finally paid for outside care on my own.”

REFERENCES

- 1.Yano EM. Toward a VA women's health research agenda. SGIM Forum. 2004:4. 9. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jordan BK, Schlenger WE, Hough R, et al. Lifetime and current prevalence of specific psychiatric disorders among Vietnam veterans and controls. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:206–15. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810270019002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fontana A, Schwartz LS, Rosenheck R. Posttraumatic stress disorder among female Vietnam veterans: a causal model of etiology. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:169–75. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.2.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zatzick DF, Weiss DS, Marmar CR, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder and functioning and quality of life outcomes in female Vietnam veterans. Mil Med. 1997;162:661–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.King DW, King LA, Foy DW, Gudanowski DM. Prewar factors in combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder: structural equation modeling with a national sample of female and male Vietnam veterans. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64:520–31. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.3.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.King LA, King DW, Fairbank JA, Keane TM, Adams GA. Resilience-recovery factors in post-traumatic stress disorder among female and male Vietnam veterans: hardiness, postwar social support, and additional stressful life events. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;74:420–34. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.2.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kang HK, Mahan CM, Lee KY, Magee CA, Mather SH, Matanoski G. Pregnancy outcomes among U.S. women Vietnam veterans. Am J Ind Med. 2000;38:447–54. doi: 10.1002/1097-0274(200010)38:4<447::aid-ajim11>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kang HK, Mahan CM, Lee KY, Magee CA, Selvin S. Prevalence of gynecologic cancers among female Vietnam veterans. J Occup Environ Med. 2000;42:1121–7. doi: 10.1097/00043764-200011000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hankin CS, Skinner KM, Sullivan LM, Miller DR, Frayne S, Tripp TJ. Prevalence of depressive and alcohol abuse symptoms among women VA outpatients who report experiencing sexual assault while in the military. J Trauma Stress. 1999;12:601–12. doi: 10.1023/A:1024760900213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frayne SM, Skinner KM, Sullivan LM, et al. Medical profile of women Veterans Administration outpatients who report a history of sexual assault occurring while in the military. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 1999;8:835–4. doi: 10.1089/152460999319156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Skinner KM, Furey J. The focus on women veterans who use Veterans Administration health care: the Veterans Administration women's health project. Mil Med. 1998;163:761–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Skinner KM, Kressin N, Frayne SM, et al. Prevalence of military sexual assault among female Veterans' Administration outpatients. J Interpers Violence. 2000;15:291–310. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barnard K, Frayne SM, Skinner KM, Sullivan LM. Health status among women with menstrual symptoms. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2003;12:911–9. doi: 10.1089/154099903770948140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frayne SM, Seaver MR, Loveland S, et al. Burden of medical illness in women with depression and posttraumatic stress disorder. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1306–12. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.12.1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weaver F, Hynes DM, Goldberg JM, Khuri S, Daley J, Henderson W. Hysterectomy in Veterans Affairs Medical Centers. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97:880–4. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01350-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weaver F, Hynes DM, Hopkinson W, et al. Preoperative risks and outcomes of hip and knee arthroplasty in the Veterans Health Administration. J Arthroplasty. 2003;18:693–708. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(03)00259-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hynes DM, Weaver F, Morrow M, et al. Breast cancer surgery trends and outcomes: results from a national Department of Veterans Affairs study. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;198:707–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2004.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lamoreaux J. The organizational structure for medical information management in the Department of Veterans Affairs: an overview of major health care databases. Med Care. 1996;34(suppl 3):MS31–44. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603001-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldzweig CL, Balekian T, Rolon C, Yano EM, Shekelle PG. The state of women veterans' health research: results of a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(3):S82–S92. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00380.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health. Bethesda, MD: NIH Publication No. 99-4385; 1999. Agenda for Research on Women's Health for the 21st Century: A Report of the Task Force on the NIH Women's Health Research Agenda for the 21st Century, Volume 1. Executive Summary. [Google Scholar]

- 21.U.S. Department of Defense, Congressionally Directed Medical Research Programs. Defense Women's Health Research Program. [January 28, 2005]. Available at: http://cdmrp.army.mil/annreports/1999annrep/section10.htm.

- 22.Institute of Medicine. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1996. The Program for Research in Military Nursing: Progress and Future Directions. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haseltine FP, Jacobson BG. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1997. Women's Health Research: A Medical and Policy Primer. [Google Scholar]

- 24.U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Women Veterans Health Program. Washington, DC: Women Veterans Health Program; 2002. Final Report of the National Women Veterans Health Strategic Work Group. [Google Scholar]

- 25.U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Advisory Committee for Women Veterans. [February 12, 2004]. Available at: http://www.va.gov/womenvet/

- 26.U.S. Department of Defense. Defense Advisory Committee on Women in the Services (DACOWITS) [January 25, 2005]. Available at: http://www.dtic.mil/dacowits/

- 27.U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development (ORD) VA R&D Women's Health Research Conference. [December 18, 2004]. Available at: http://www1.va.gov/resdev/programs/womens_health/conference/default.cfm.

- 28.Finnegan LP. The NIH Women's Health Initiative: its evolution and expected contributions to women's health. Am J Prev Med. 1996;12:292–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Riley PL, Finnegan LP. Observations from the CDC: the prevention research centers program: collaboration in women's health. J Womens Health. 1997;6:281–3. doi: 10.1089/jwh.1997.6.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Correa-de-Araujo R. A wake-up call to advance women's health. Women's Health Issues. 2004;14:31–4. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bierman AS. Climbing out of our boxes. Advancing women's health for the twenty-first century. Women's Health Issues. 2003;13:201–3. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2003.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Satcher D. American women and health disparities. JAMWA. 2001;56:131–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]