Abstract

BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVE

Effects of advances in Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) women's health care on women veterans' health care decision making are unknown. Our objective was to determine why women veterans use or do not use VA health care.

DESIGN AND PARTICIPANTS

Cross-sectional survey of 2,174 women veteran VA users and VA-eligible nonusers throughout southern California and southern Nevada.

MEASUREMENTS

VA utilization, attitudes toward care, and socio-demographics.

RESULTS

Reasons cited for VA use included affordability (67.9%); women's health clinic (WHC) availability (58.8%); quality of care (54.8%); and convenience (47.9%). Reasons for choosing health care in non-VA settings included having insurance (71.0%); greater convenience of non-VA care (66.9%); lack of knowledge of VA eligibility and services (48.5%); and perceived better non-VA quality (34.5%). After adjustment for socio-demographics, health characteristics, and VA priority group, knowledge deficits about VA eligibility and services and perceived worse VA care quality predicted outside health care use. VA users were less likely than non-VA users to have after-hours access to nonemergency care, but more likely to receive both general and gender-related care from the same clinic or provider, to use a WHC for gender-related care, and to consider WHC availability very important.

CONCLUSIONS

Lack of information about VA, perceptions of VA quality, and inconvenience of VA care, are deterrents to VA use for many women veterans. VA WHCs may foster VA use. Educational campaigns are needed to fill the knowledge gap regarding women veterans' VA eligibility and advances in VA quality of care, while VA managers consider solutions to after-hours access barriers.

Keywords: women's health services, ambulatory care/utilization, hospitals, veterans/utilization, health services accessibility, decision making, choice behavior

Women are one of the fastest growing segments of the veteran population. Currently, 15% of active duty military and 20% of new military recruits are women. By the year 2010, women are projected to comprise 10% of the veteran population.1 Historically, the growing presence of women veterans in Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care facilities highlighted gaps in women's VA access and quality of care, and led to Congressional legislation that authorized the VA to provide women's health care services.2–5 Although research conducted prior to the institution of these reforms demonstrated gender-related barriers to VA use,6 the effects of these advances on women veterans' current health care decision making are unknown.

Among veterans in general, low income, lack of medical insurance, poor health status, having a military service-connected disability, and being an ethnic minority predict VA use.7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 Compared with male veterans, women veterans are more likely to have low income, lack insurance, have poor health status, and be an ethnic minority group member; however, their proportionate use of VA ambulatory care services remains less than that of male veterans.13–15 This suggests that additional gender-related influences on VA use remain.

Our objective was to assess the reasons that women veterans use or do not use VA health care. Because of the historical gaps in care, we hypothesized that lack of knowledge of VA benefits and longstanding perceptions of deficits in VA care quality may remain significant factors in their choice of VA versus non-VA health care delivery.

METHODS

Study Design and Subjects

Between March and September 2004, we conducted a telephone survey among VA-eligible women veterans residing in southern California and southern Nevada, corresponding to the Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN) 22. To create the sampling frame, we cross-linked Veterans Health Administration, Veterans Benefits Administration, and Department of Defense databases, and then identified all women veterans with a VISN22 residential ZIP code. We randomly selected potential participants stratified by ambulatory care user type (VA user, VA nonuser), age group (less than 50 years old, 50 and older), and for VA nonusers, also stratified by the source database. VA users were defined as anyone making an outpatient health care visit to the VA in the prior 12 months. We enrolled similar number from each user type/age group strata so that we could increase the precision of our estimates for the smaller groups. To determine the sample size distribution within the 2 VA nonuser strata, from each source database we used proportional allocation based on the percent of VA nonusers in that database. The rationale for this approach was to minimize the effects of potential systematic biases in the databases that may be associated with decision making about VA health care use.

Fieldwork was conducted by a survey research firm with expertise in veteran and health services research surveys. An advance information packet was mailed to each sampled veteran randomly selected to participate in the telephone survey. Study interviewers were experienced female interviewers who completed project-specific training. Interviewers screened respondents for study eligibility prior to obtaining consent and conducting the telephone survey. Potential respondents were offered study enrollment if they were not currently serving on active duty or employed by the VA, and did not volunteer that they were too ill to participate in a telephone interview. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of all 5 VISN22 VA Medical Centers and the Office of Management and Budget.

Conceptual Framework and Survey Measures

The Behavioral Model of Health Services Utilization is the conceptual framework that guided this investigation.16–18 This framework describes factors that predict health care use as a function of a predisposition to use health care services, factors that enable or impede such use, and need for care.16 Ambulatory care user type was confirmed based on respondent self-reported sites for health care in the prior 12 months. Three ambulatory care user types were defined: VA users, non-VA users whose ambulatory care use was limited to settings outside the VA, and nonusers of any health care services in the prior 12 months. We assessed several features of ambulatory care utilization, including whether the respondent had an identified usual provider for health care, had access to evening or weekend appointments for routine care, and used a women's health provider or clinic for women's health care.

Reasons for choosing VA or non-VA sites of health care, barriers to VA use, health care delivery preferences, knowledge of VA eligibility and services, and perceptions of VA care were assessed using measures developed from focus group discussions in VA-eligible women veterans. Reasons for choice of provider and barriers to VA use were assessed as dichotomous measures, where respondents could select each reason that applied. We measured perception of VA quality of care using a modified 0-to-10 scale from the Consumer Assessment of Health Plans Survey (CAHPS) global rating of health care.19 To control for other factors in the Behavioral Model associated with health services use, we assessed age, education, employment status, marital status, annual income, health insurance, health status (measured with the SF-12), and number of diagnosed medical conditions.20, 21 Priority for VA enrollment is determined on the basis of service-connected disability rating, income, and other factors, with veterans in the highest priority groups (priority groups 1 to 6) having no co-payment for VA care. Therefore, we also assessed VA service-connected disability rating and VA priority group.

Statistical Analysis

Our main comparisons are between women veterans who use the VA and those who use only non-VA health care services. We also evaluated nonusers' knowledge and perceptions to determine what may influence their decision to use VA health care services when needed. VA users were compared both with non-VA users and nonusers on socio-demographic, health-related, and ambulatory care use characteristics using χ2 tests for categorical variables and t tests for continuous measures.

We dichotomized ratings of perceived VA quality as 8 or higher on the 10-point scale versus less than 8 to afford appropriate discrimination across user groups and allow for hypothesis testing regarding significantly above average quality perceptions, consistent with the CAHPS analytic principle dictating compression of skewed quality rating scales.22 Applying this same principle, we dichotomized all ordinal scales to the most extreme response versus all other responses. We dichotomized 4-point Likert scales at the midpoint.

To determine health care delivery preferences and VA perceptions independently predicting VA ambulatory care use, we conducted multinomial (polychotomous) logistic regression adjusting for behavioral model domains thought to affect health services use.23 We addressed collinearity by examining the intercorrelations among independent variables and selecting 1 variable from each correlated subset. We also reran the multinomial logistic regression model on the subgroup of highest VA eligibility (priority groups 1 to 6) to ascertain differential influences on VA use. We applied logistic regression analysis to further evaluate independent socio-demographic predictors of gaps in knowledge and quality perceptions.

Sampling weights were developed from the inverse of the probabilities of inclusion in the sample and normalized so that the weighted sum matched the total sample size. All analyses applied weights to account for disproportional allocation of the population by strata, so that resulting estimates are representative of the general VISN22 women veteran population. Univariate analyses were conducted using the SAS statistical software system, version 8.2.24 The multinomial logistic regression analyses were conducted using STATA version 7.0.25

RESULTS

Demographics and Health Status

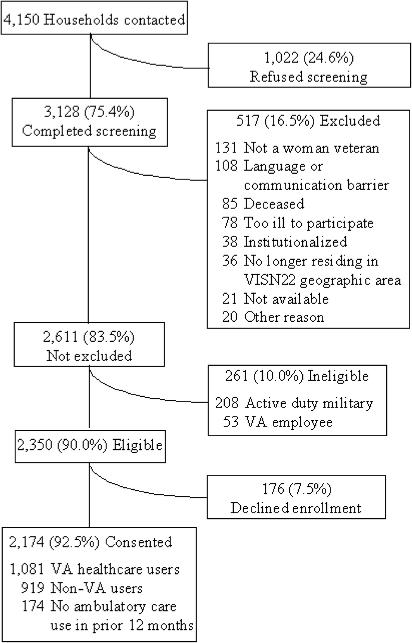

Results of survey recruitment are presented in Figure 1. Characteristics of the women veteran population by user-type are presented in Table 1. VA users were similar in age, race-ethnicity, and period of military service to non-VA users, but were more likely to be unemployed, disabled, have an annual household income less than $20,000, be uninsured, and have a VA service-connected disability. VA users had worse health than non-VA users on all health-related measures, with lower SF-12 physical (mean difference vs non-VA users 7.2 points; 95% confidence interval [CI] 5.4, 8.9) and mental (mean difference 5.5 points; 95% CI 4.0, 7.0) component scores. Among VA users, 84.7% were in VA high-priority groups based on having a VA service-connected disability and/or low income, whereas 57.0% of non-VA users and 52.0% of ambulatory care nonusers were in these high-priority groups (P<.0001 for both comparisons). Compared with non-VA users, VA users were more likely to report mental health care or prescription benefits as the main health care service used in the prior 12 months (both P<.0001).

FIG. 1.

Results of survey recruitment.*

*Based on respondent characteristics from administrative data, respondents from households that completed screening or consented to study enrollment were more likely to be VA users (P<.05), but did not differ from those who refused screening or enrollment, respectively, in age group or race/ethnicity.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Women Veterans by Type of Ambulatory Care Use

| Total (n=2,174) | VA Users (n=1,081) | Non-VA Users (n=919) | Nonusers (n=174) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socio-demographic characteristics | ||||

| Age (mean y±SD) (y) | 50.4±18.2 | 51.6±6.7 | 51.0±25.2 | 45.8±21.9* |

| Age (%) | † | |||

| 18 to 44 | 41.6 | 35.3 | 40.9 | 49.9 |

| 45 to 64 | 35.5 | 41.4 | 34.7 | 36.3 |

| 65 or older | 23.0 | 23.4 | 24.4 | 13.8 |

| Race/ethnicity (%) | * | |||

| White | 65.1 | 67.0 | 65.6 | 60.7 |

| African American | 11.9 | 16.3 | 12.9 | 2.9 |

| Hispanic | 15.2 | 8.6 | 13.8 | 28.8 |

| Other | 7.8 | 8.2 | 7.7 | 7.6 |

| Married (%) | 59.2 | 41.3 | 59.2* | 71.2* |

| College graduate (%) | 35.9 | 29.7 | 37.6‡ | 28.9 |

| Length of military service 20 or more years (%) | 28.6 | 12.0 | 29.9* | 31.8* |

| Period of military service (%) | * | |||

| Pre-Vietnam | 21.0 | 23.7 | 22.0 | 12.8 |

| Vietnam | 6.7 | 9.6 | 6.8 | 4.2 |

| Post-Vietnam to present | 72.3 | 66.8 | 71.2 | 82.9 |

| Employment (%) | ||||

| Working full or part time | 54.1 | 41.6 | 56.9* | 44.6 |

| Unemployed | 4.2 | 8.9 | 3.0* | 8.8 |

| Disabled | 2.2 | 16.1 | 1.0* | 0.6* |

| Annual household income<$20,000 (%) | 13.7 | 32.4 | 12.4* | 9.3* |

| Has health insurance (%) | 88.4 | 54.0 | 93.7* | 77.8* |

| Health related characteristics | ||||

| VA service-connected disability rating category (%) | * | * | ||

| 50 to 100 | 7.1 | 19.3 | 6.1 | 5.1 |

| 10 to 40 | 21.2 | 28.2 | 21.7 | 13.6 |

| Not service-connected | 71.7 | 52.5 | 72.2 | 81.2 |

| VA priority group 1 to 6 (%) | 58.9 | 84.7 | 57.0* | 52.0* |

| Self-reported health fair or poor | 14.0 | 31.6 | 13.1* | 7.5* |

| Mean SF-12 physical component score § | 46.7 | 39.7 | 46.9* | 49.7* |

| Mean SF-12 mental component score § | 53.1 | 48.0 | 53.5* | 54.2* |

| Number of diagnosed medical conditions | * | * | ||

| 0 | 29.5 | 12.8 | 27.7 | 51.9 |

| 1 | 25.4 | 18.1 | 26.3 | 24.0 |

| 2 | 23.4 | 23.3 | 24.6 | 15.5 |

| 3 or more | 21.8 | 45.8 | 21.4 | 8.6 |

| Health care use characteristics | ||||

| Main health care service used past year (%) | * | |||

| Primary or specialty care | 71.0 | 88.9 | – | |

| Mental health | 13.5 | 2.8 | – | |

| Prescriptions | 13.9 | 5.8 | – | |

| Emergency or other | 1.6 | 2.5 | – | |

P<.001 compared with VA users.

P=.003 compared with V users.

P=.03 compared with VA users.

Range 0 to 100, higher score denotes better health.

VA users also differed significantly on most socio-demographic and health-related measures compared with women veterans who used no health care services in the past 12 months. VA users were more likely to be disabled, low income, uninsured, have a VA service-connected disability, be in a VA high-priority group, or in poor health (P<.0001 for all comparisons). Nonusers were younger and more likely to be Hispanic.

Reasons for Choice of VA Versus Non-VA Health Care Setting

VA users cited affordability (67.9%), availability of a women's health clinic (WHC) (58.8%), quality of care (54.8%), and convenience (47.9%) as reasons for VA use. Among non-VA users, commonly cited reasons for not using VA health care were already paying for insurance that covers health care outside the VA (71.0%), greater convenience of non-VA care (66.9%), lack of knowledge of VA eligibility and benefits (48.5%), and perception that quality of care is better in settings outside the VA (34.5%).

Table 2 shows VA knowledge and perceptions and health care delivery preferences by type of ambulatory care use. Non-VA users were more likely than VA users to report having none or almost none of the information they need regarding VA health care benefits (53.9% vs 5.2%, P<.0001), and were more likely to believe that VA eligibility is restricted to veterans with service-connected disabilities (43.7% vs 21.9%, P<.0001). Table 3 shows socio-demographic predictors of having VA knowledge gaps and low-quality perceptions. Among non-VA users, younger women were more likely than older women to report information deficits for each of these measures, even after adjusting for factors associated with health care use (adjusted odds ratios (ORs) 1.6, 2.0, and 1.3 for VA benefits, eligibility, and service availability knowledge gaps, respectively).

Table 2.

VA Knowledge and Perceptions and Health Care Delivery Preferences by Type of Ambulatory Care Use

| Total (n=2,174) | VA Users (n=1,081) | Non-VA Users (n=919) | Nonusers (n=174) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VA eligibility and benefits information (%) | ||||

| Knowledge gap for VA benefits* | 48.8 | 5.2 | 53.9† | 45.3† |

| Knowledge gap for VA eligibility‡ | 42.7 | 21.9 | 43.7† | 50.3† |

| Knowledge gap for availability of VA women's health services§ | 42.7 | 20.7 | 45.3† | 40.8† |

| VA quality perception (%) | ||||

| VA quality 8 or higher on 10-point scale | 34.7 | 73.0 | 28.7† | 38.3† |

| VA physicians not skilled in treating women¶ | 35.3 | 21.7 | 38.1† | 28.5 |

| Women veterans not made to feel welcome at VA¶ | 16.2 | 10.2 | 17.5∥ | 12.9 |

| Convenience of ambulatory care (%) | ||||

| Has usual provider for health care (PCP) | 72.7 | 77.5 | 76.2 | 47.5† |

| Has PCP continuity usually available | 58.8 | 54.4 | 62.4** | 38.7†† |

| Availability of routine care after hours very important‡‡ | 27.0 | 32.4 | 27.0 | 22.2** |

| Has routine care available after hours | 28.6 | 16.5 | 30.7† | 18.1 |

| Receiving both general and women's health care from same provider or clinic very important‡‡ | 50.3 | 55.4 | 49.2 | 53.5 |

| Gets both general and women's health care from same provider or clinic | 60.1 | 57.9 | 58.6 | 77.4† |

| Women's health care delivery (%) | ||||

| Availability of a women's health clinic very important‡‡ | 29.8 | 44.3 | 28.9† | 25.8† |

| Having a female MD for women's health care very important‡‡ | 30.6 | 43.4 | 30.1† | 25.3† |

| Gets women's health care from MD or clinic just for women | 27.1 | 51.6 | 25.4† | 21.2† |

Respondent has none or almost none of the information they need about VA health care benefits (vs having all, most, or some of information needed, or VA health care benefits information not needed).

P<.001 compared with VA users.

Agreement with statement that only veterans who had an illness or injury connected to their military service are eligible for VA health care.

Respondent thought service was offered (definitely or probably) by VA (vs probably or definitely not offered).

Agreement (strongly or somewhat) with statement (vs somewhat or strongly disagrees).

P=.01 compared with VA users.

P=.04 compared with VA users.

P=.001 compared with VA users.

Measured using 4-point scale of the importance (very important to not important at all) of that health care delivery feature, then dichotomized to very important versus all other.

Table 3.

Adjusted Odds Ratios Predicting VA Information Deficits and Perceptions of Low VA Quality*

| Characteristic | Knowledge Gap for VA Benefits Information | Knowledge Gap for VA Eligibility | Knowledge Gap for Availability of VA Women's Health Services | Perceived Low VA Quality of Care |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age <50 y | 1.6† | 2.0† | 1.3‡ | 1.9† |

| No diagnosed medical conditions | 1.4§ | 1.1 | 1.4¶ | 0.8 |

| Overall health excellent or very good | 0.9 | 1.2 | 0.6† | 0.6∥ |

| Employed | 1.5† | 0.8¶ | 1.5† | 2.2† |

| VA use | 0.05† | 0.4† | 0.3† | 0.1† |

All models adjusted for the characteristics listed.

P<.001.

P=.03.

P=.003.

P=.01.

P=.001.

In contrast to VA quality ratings by VA users, only 28.7% of non-VA users rated VA quality high (P<.0001) (Table 2). Non-VA users were also more likely to perceive VA physicians as not being skilled in treating women (38.1% vs 21.7%, P<.0001) and an unwelcome VA environment (17.5% vs 10.2%, P<.05). Younger women veterans were especially more likely to perceive poor VA quality of care (Table 3, adjusted OR 1.9).

VA users and non-VA users were equally likely to identify a usual-care-provider and to receive both general and gender-specific care from the same provider or clinic (Table 2). However, VA users were less likely to have primary care continuity (62.4% vs 54.4%, P<.05) or after-hours access for nonemergency care (30.7 vs 16.5, P<.005). VA users were more likely to report preferences for using a women's health provider (P<.0001) or clinic (P<.005) when obtaining gender-specific care, and reported greater use of WHCs for their gender-related care (P<.0001).

Nonusers' Knowledge and Perceptions of VA

Compared with VA users, nonusers had substantial knowledge deficits of VA benefits, eligibility, and availability of women's health care service (P<.0001 for all comparisons) (Table 2). VA users and nonusers also differed in perceptions of VA quality, with nonusers less likely to perceive VA quality as high (38.3% vs 73.0%, P<.0001).

Independent Predictors of Type of Ambulatory Care Use

Independent predictors of type of ambulatory care services used are presented in Table 4. Comparing non-VA users with VA users, regardless of VA priority group membership, deficits in knowledge of VA benefits (adjusted OR 40.7 for high-priority non-VA user vs VA user) and deficits in knowledge of VA availability of women's health services (adjusted OR 3.6) predicted non-VA use, whereas perceived high VA quality of care predicted VA use (adjusted OR 0.2). Availability of routine care after hours also was associated with non-VA use (adjusted OR 5.0), whereas considering availability of a WHC to be very important (adjusted OR 0.4) and receiving both general and gender-specific care from the same clinic or provider (adjusted OR 0.5), were correlated with VA use.

Table 4.

Independent Predictors of Type of Ambulatory Care Use: Results of Multinomial Logistic Regression

| Non-VA Users Vs VA Users Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Nonusers Versus VA Users Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Priority Groups | Priority 1 to 6 | All Priority Groups | Priority 1 to 6 | |

| Traditional measures | ||||

| Socio-demographic | ||||

| Age | 1.0 (1.001, 1.04) | 1.0 (0.99, 1.04) | 1.0 (0.95, 1.02) | 1.0 (0.9, 1.04) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) |

| African American | 2.0 (0.99, 4.2) | 1.7 (0.8, 3.8) | 0.2 (0.1, 0.7) | 1.0 (0.2, 4.6) |

| Hispanic | 1.0 (0.4, 2.2) | 0.6 (0.3, 1.6) | 1.4 (0.4, 5.1) | 3.3 (0.8, 13.4) |

| Other | 1.6 (0.8, 3.2) | 1.5 (0.6, 3.5) | 0.2 (0.0, 0.9) | 0.7 (0.1, 3.2) |

| Married | 2.1 (1.1, 3.7) | 2.0 (1.03, 3.8) | 2.9 (0.9, 9.6) | 2.1 (0.7, 6.1) |

| Working full or part-time | 1.0 (0.6, 1.8) | 1.2 (0.6, 2.4) | 0.3 (0.1, 0.9) | 0.3 (0.1, 1.1) |

| Annual household income<$20,000 | 0.4 (0.2, 0.8) | 0.5 (0.2, 1.03) | 0.3 (0.1, 1.5) | 0.3 (0.1, 1.7) |

| Health related | ||||

| Has VA service-connected disability | 0.5 (0.2, 0.8) | 0.5 (0.2, 0.96) | 0.5 (0.2, 1.5) | 0.5 (0.1, 2.0) |

| SF-12 physical component score* | 2.2 (1.8, 2.8) | 2.1 (1.6, 2.7) | 3.6 (2.2, 5.9) | 3.2 (1.8, 5.7) |

| SF-12 mental component score* | 2.1 (1.7, 2.6) | 2.0 (1.6, 2.6) | 2.4 (1.4, 4.3) | 1.5 (0.96, 2.3) |

| Gender and veteran related measures | ||||

| VA eligibility and benefits info | ||||

| Knowledge gap for VA benefits | 33.3 (15.1, 73.4) | 40.7 (16.3, 101.4) | 20.2 (6.5, 63.0) | 63.8 (13.3, 306.8) |

| Knowledge gap for VA eligibility | 1.3 (0.7, 2.3) | 1.5 (0.8, 2.8) | 3.9 (1.4, 11.0) | 1.4 (0.4, 4.9) |

| Knowledge gap for availability of VA women's health services | 3.5 (2.0, 6.1) | 3.6 (1.9, 6.9) | 2.4 (0.8, 7.0) | 1.6 (0.4, 7.0) |

| VA quality perception | ||||

| VA quality 8 or higher on 10-point scale | 0.1 (0.1, 0.2) | 0.2 (0.1, 0.3) | 0.3 (0.1, 0.8) | 0.3 (0.1, 0.98) |

| Women veterans not made to feel welcome at VA | 1.0 (0.5, 1.9) | 0.9 (0.4, 2.2) | 0.5 (0.1, 2.5) | 0.2 (0.0, 1.1) |

| Convenience of ambulatory care | ||||

| Has primary care provider continuity usually available | 2.4 (1.3, 4.1) | 1.7 (0.9, 3.3) | 2.0 (0.8, 5.1) | 2.2 (0.8, 6.1) |

| Availability of routine care after hours very important | 0.9 (0.5, 1.6) | 1.0 (0.5, 2.0) | 0.7 (0.2, 2.2) | 0.1 (0.0, 0.4) |

| Has routine care available after hours | 5.9 (3.0, 11.4) | 5.0 (2.5, 10.0) | 2.0 (0.5, 8.4) | 1.1 (0.2, 5.8) |

| Receiving both general and women's health care from same provider or clinic very important | 0.8 (0.5, 1.3) | 0.7 (0.4, 1.3) | 1.3 (0.5, 3.2) | 0.5 (0.2, 1.5) |

| Gets general and women's health care from same place | 0.5 (0.3, 0.9) | 0.5 (0.2, 0.9) | 0.8 (0.3, 2.5) | 2.1 (0.5, 8.9) |

| Women's health care delivery | ||||

| Availability of a women's health clinic very important | 0.4 (0.2, 0.8) | 0.4 (0.2, 0.8) | 0.4 (0.1, 1.5) | 0.3 (0.1, 1.2) |

| Having a female MD for women's health care very important | 0.6 (0.3, 1.1) | 0.5 (0.2, 0.9) | 0.2 (0.0, 0.7) | 0.1 (0.0, 0.5) |

Range 0 to 100, higher score denotes better health.

For nonusers compared with VA users, regardless of VA priority group membership, deficits in knowledge of VA benefits predicted nonuse of care (adjusted OR 63.8 for high-priority nonuser vs VA user comparison), whereas perceived high VA quality of care predicted VA use (adjusted OR 0.3).

DISCUSSION

Eighty-seven percent of women veterans do not use VA health care services.15 We found that for many of these women veterans, lack of knowledge of their eligibility for VA services, perceptions of poor VA quality of care, and inconvenience of VA care, are deterrents to VA use. Surprisingly, having a knowledge gap about VA benefits was the strongest predictor of both nonuse of care and of non-VA use, even among women veterans in the highest VA priority groups. This means that many women veterans are failing to capitalize on services for which they are eligible. Unfortunately, first noted in the 1982 General Accounting Office (GAO) studies, this information gap has persisted over time and may require greater attention and resources than was previously afforded targeted outreach and education efforts.2 In fact, we found that younger women veterans today have less knowledge about VA eligibility and services than their older counterparts, even after controlling for health characteristics associated with health care need. Insofar as knowledge of VA eligibility and services is acquired through contacts with other veterans over time, the cumulative nature of such information sources could account for this finding.

Women veterans who use the VA have much higher opinions of VA quality of care than women veterans who do not use the VA. There are several potential explanations for this finding. Approximately 39% of women veteran VA users also use non-VA care,26 but only about 5% of non-VA users formerly used the VA.15 Therefore, VA users' quality perceptions may be based upon direct comparisons with non-VA services, but non-VA users' perceptions, for the most part, are based upon word-of-mouth, media depictions of the VA, and other indirect sources. Starting in the mid-1990s, the VA undertook a system-wide reorganization to focus on quality of care, and is now considered by the Institute of Medicine to be a leader in health care quality.27–31 However, veterans who rely on health care outside the VA may have outdated perceptions of VA quality based on the VA's historical reputation. Alternatively, as women constitute a minority of VA health care users, VA quality measures may not adequately reflect VA women's health care. We found that women veteran VA users differ from women veteran non-VA users on a number of socio-demographic and health characteristics. If they also differ in their assessments of health care quality, then that could also account for the differences we noted as well.

We also identified a number of institutional or health care system-level characteristics associated with women veterans' choice of health care setting, offering potentially actionable areas for improving women veterans' VA access. VA users consider availability of a women's health provider or clinic for women's health care to be very important, and to use this feature of care. In contrast to ambulatory care settings in the private sector in which a majority of health care users are female, the VA health care system is unique in its male-dominated gender ratio. Women's health clinics may be preferred by women veterans who seek care in the VA as an option to the male-dominated environments in the rest of the clinic settings. This may be especially true among women veterans with a history of military sexual trauma.

Several methodologic limitations of this study are important to note. First, our sampling methods and interview procedures relied on telephone contacts. Our sample therefore excludes, for example, homeless women veterans who are likely to have a higher prevalence of financial barriers to care and may experience unique barriers to care in VA and other settings. Our sampling frame also focused on southern California and southern Nevada, areas that have greater population density and diversity and a somewhat higher percentage of VA medical facilities with WHCs compared with the rest of the country. In comparison with the 2001 National Survey of Veterans, our sample has higher income and education, and lower rates of disability than women veterans in other geographic areas,32 and therefore may differ in health care use as well. Ultimately, in order to adequately plan for the rapidly changing landscape of delivering high-quality accessible women's health care in the VA, translation of this regional study into a national appraisal of women veterans' needs, preferences, and patterns of care would provide a valuable evidence base for strategic planning. In fact, the last national survey of female veterans was conducted 20 years ago, and the Advisory Committee on women veterans has made the conduct of a repeat national study one of their high-priority recommendations.11, 33

Despite these limitations, this study represents one of the most comprehensive population-based assessments of women veterans' needs, preferences, and choices yet conducted. Our expanded model for evaluating women veterans' VA ambulatory care use contributes to the existing literature on women's access to and utilization of health care services in several important ways. First, using the traditional patient-level sociodemographic and health-related predictors of VA ambulatory care use, our findings are consistent with those described in prior research on women veterans' VA use.7, 11, 14, 34 Our further incorporation of gender-related, veteran-related, and health care system-level domains into the behavioral model framework demonstrates a broader range of factors that are influencing women veterans' health care decision making. Given the changing demographics of women veterans,34 and the greater VA knowledge deficits and lower quality perceptions we found among younger women veterans, our findings provide key insights into the barriers women veterans are facing in accessing VA care, and provide a foundation for understanding and acting upon inaccurate perceptions and mutable system characteristics.

The VA has made significant advances in improving the quality and outcomes of care afforded veteran users of what constitutes the largest health care system in the United States.27–30, 31 While originally driven by legislation, advances in VA health care for women veterans have produced a marked expansion of available women's health care services,35 and the development of WHCs in many VA settings as a delivery model to address women veteran concerns regarding the VA environment and care.36 Nonetheless, many women veterans remain unaware of these initiatives to address their health care needs in VA settings. Comprehensive educational and outreach campaigns are needed to fill the information gap regarding women veterans' VA eligibility and advances in VA quality of care, while VA managers consider possible solutions to after-hours access barriers. Future research should also be directed toward exploring the contribution of VA WHCs and other innovations designed to meet women veterans' health care needs, and to determine the degree to which they may foster improved access to and use of VA health care services.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research and Development Service (#GEN-00-082). Dr. Washington is supported by an Advanced Research Career Development Award from the Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Service (#RCD-00-017). The authors gratefully acknowledge Mark Canning for overall project management, Barbara Sasso for assistance with survey development, Martin Lee, PhD, for statistical assistance, and the site principal investigators Leslie Satz, MSN, ANP, Stuart Gilman, MD, MPH, Nancy McNulty, MSN, ANP, and Denise Bartlett-Chekal, MSN, FNP. We also thank James Strike and Rick Paulson of the VA Austin Automation Center and Patricia Murphy of the VA Information Resource Center (VIReC) for assistance with sample development, and California Survey Research Services Inc. for survey fieldwork. The views expressed within are solely those of the authors, and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

REFERENCES

- 1.Montrey JS. Issues in health care for women veterans. Veterans Health Syst J. 2000;5:32–46. [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. General Accounting Office. Actions needed to insure that female veterans have equal access to VA benefits. 1982. (GAO/HRD-82)

- 3.U.S. General Accounting Office. VA health care for women: despite progress, improvements needed. January 1992 (GAO/HRD-92-93)

- 4.U.S. General Accounting Office. VA health care for women, progress made in providing services to women veterans. 1999. (GAO/HEHS-99-38)

- 5. Public Laws 98-160, 102-585, 103-446.

- 6.VA Office of Planning and Management Analysis. Washington: Department of Veteran Affairs; 1989. Survey of Disabled Veterans. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ouimette P, Wolfe J, Daley J, Gima K. Use of VA health care services by women veterans: findings from a national sample. Women Health. 2003;38:77–91. doi: 10.1300/J013v38n02_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Washington DL, Harada ND, Villa VM, et al. Racial variations in Department of Veterans Affairs ambulatory care use and unmet health care needs. Mil Med. 2002;167:235–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Washington DL, Villa V, Brown A, Damron-Rodriguez J, Harada N. Racial/ethnic variations in patterns of VA ambulatory care use. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:2231–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.043570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Skinner KM, Furey J. The focus on women veterans who use Veterans Administration health care: the VA women's health project. Mil Med. 1998;163:761–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Romeis JC, Gillespie KN, Thorman KE. Female veterans' use of health care services. Med Care. 1988;26:589–95. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198806000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kosloski K, Austin C, Borgatta E. Determinants of VA utilization: the 1983 Survey of Aging Veterans. Med Care. 1987;25:830–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Skinner K, Sullivan LM, Tripp TJ, et al. Comparing the health status of male and female veterans who use VA health care: results from the VA women's health project. Women Health. 1999;294:17–33. doi: 10.1300/J013v29n04_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoff RA, Rosenheck RA. Female veterans' use of Department of Veterans Affairs health care services. Med Care. 1998;36:1114–9. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199807000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Department of Veterans Affairs, Medical SAS Outpatient Dataset, fiscal year 2003. [August 26, 2005]. Available at: http://www.virec.research.med.va.gov/DataSourcesName/Medical-SAS-Datasets/SAS.htm.

- 16.Andersen R. A Behavioral Model of Families' Use of Health Services. Research Series No. 25. Chicago: Center for Health Administration Studies; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andersen R. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aday LA, Awe WC. Health services utilization models. In: Gochman DS, editor. Handbook of Health Behavior Research I: Personal and Social Determinants. New York: Plenum Publishing Corporation; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ); 2002. [August 26, 2005]. CAHPS 3.0 Health Plan Survey: Adult Commercial Instrument, CAHPS® Health Plan Survey and Reporting Kit 2002. Available at: http://www.cahps-sun.org. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stewart AL, Hays RD, Ware JE. The MOS short-form general health survey: reliability and validity in a patient population. Med Care. 1988;26:724–35. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198807000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–33. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1999. [August 26, 2005]. Frequently Asked Questions: Consumer Assessment of Health Plans (CAHPS®) Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/cahps/faqtoc.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harrell F. Regression Modeling Strategies. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2001. pp. 204–5. [Google Scholar]

- 24.SAS Institute Inc. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 1993. SAS/STAT User's Guide, version 6.12. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stata Corporation. College Station, TX: Stata Press; 2001. Stata Reference Manual: Release 7. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bean-Mayberry B, Chang C, McNeil M, Hayes P, Scholle SH. Comprehensive care for women veterans: indicators of dual use of VA and non-VA providers. JAMWA. 2004;59:192–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kizer KW. The “New VA”: a national laboratory for health care quality management. Am J Med Qual. 1999;14:3–20. doi: 10.1177/106286069901400103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perlin JB, Kolodner RM, Roswell RH. The Veterans Health Administration: quality, value, accountability, and information as transforming strategies for patient-centered care. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10(pt 2):828–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jha AK, Perlin JB, Kizer KW, Dudley RA. Effect of transformation of the Veterans health care system on the quality of care. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2218–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa021899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Asch SM, McGlynn EA, Hogan MM, et al. Comparison of quality of care for patients in the Veterans Health Administration and patients in a national sample. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:938–45. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-12-200412210-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Institute of Medicine. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2002. Leadership by Example: Coordinating Government Roles in Improving Health Care Quality. [Google Scholar]

- 32.2001 National Survey of Veterans (NSV) Final Report. Washington, DC: Department of Veteran Affairs; 2001. [June 15, 2005]. Available at: http://www.va.gov/vetdata/SurveyResults/final.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 33.VA Advisory Committee on Women Veterans 2004 Report. 2004. [June 15, 2005]. Available at: http://www1.va.gov/womenvet/docs/2004_ACWV_Report.pdf.

- 34.Stern A, Wolfe J, Daley J, Zaslavsky A, Roper SF, Wilson K. Changing demographic characteristics of women veterans: results from a national sample. Mil Med. 2000;165:773–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Washington DL, Caffrey C, Goldzweig C, Simon B, Yano EM. Availability of comprehensive women's health care through Department of Veterans Affairs medical centers. Women's Health Issues. 2003;13:50–4. doi: 10.1016/s1049-3867(02)00195-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yano EM, Washington DL, Goldzweig C, Caffrey C, Turner C. The organization and delivery of women's health care in Department of Veterans Affairs medical centers. Women's Health Issues. 2003;13:55–61. doi: 10.1016/s1049-3867(02)00198-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]