Abstract

We have designed a nanosensor to study the potential function of metallothionein (MT) in metal transfer and its interactions with redox partners and ligands by attaching two fluorescent probes to recombinant human MT. The specific labeling takes advantage of two different modification reactions. One is based on the fact that recombinant MT has a free N-terminal amino group when produced by the IMPACT T7 expression and purification system, the other on the observation that one human MT isoform (1b) contains an additional cysteine at position 32. It is located in the linker region of the molecule, allowing the introduction of a probe between the two domains. An S32C mutation was introduced into hMT-2. Its thiol reactivity, metal binding capacity, and CD and UV spectra all demonstrate that the additional cysteine contains a free thiol(ate); it perturbs neither the overall structure of the protein nor the formation of the metal/thiolate clusters. MT containing only cadmium was labeled stoichiometrically with Alexa 488 succinimidyl ester at the N terminus and with Alexa 546 maleimide at the free thiol group, followed by conversion to MT containing only zinc. Energy transfer between Alexa 488 (donor) and Alexa 546 (acceptor) in double-labeled MT allows the monitoring of metal binding and conformational changes in the N-terminal β-domain of the protein.

The fact that metallothionein (MT) completely lacks aromatic amino acids and that its zinc is spectroscopically silent has precluded direct biophysical studies of zinc binding. The resultant experimental dilemma has been compounded by a lack of methods by which to attach extrinsic probes to this small protein of ≈60 amino acids for the investigation of structure/function relationships. Cysteines and lysines are the only amino acid side chains with functional groups amenable to labeling in MT. However, all 20 cysteines are bound to seven zinc atoms in two zinc/thiolate clusters, in which each zinc atom is coordinatively saturated with four cysteine ligands. These cysteines cannot be modified chemically without severely perturbing or destroying the structure of the clusters. The multiplicity of the eight lysines also presents problems for specific modifications.

We nevertheless have succeeded in labeling MT with fluorescent probes to overcome these obstacles. A differential chemical modification of the cysteines in the presence and absence of a chelating agent has previously allowed us to label the apoprotein thionein (T) in the presence of MT and to label the entire pool MT + T (1). These reactions now constitute the basis for a very sensitive fluorimetric method that detects both MT and T in rat tissues where they occur in comparable amounts. Here, we extend these studies by introducing yet other specific fluorescent probes into MT. Although MTs usually have an acetylated N terminus, we took advantage of the fact that the protein is isolated with a free N terminus when expressed with the IMPACT T7 system (2), thus allowing labeling of the N-terminal amino group without modifying any of the amino groups of the eight lysines. Site-specific incorporation of a second fluorescent probe would yet be needed to perform fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) experiments that could probe protein conformation in response to metal and ligand binding. For this, we recognized that the sequence of one particular isoform of human MT (hMT)-1b contains an additional cysteine, i.e., 21 instead of the usual 20 (3). This cysteine is located at position 32 in the linker region between the two MT domains containing the zinc/thiolate clusters. However, the characteristics of this isoprotein are unknown, in particular whether the additional cysteine participates in the formation of the clusters or is a “free” cysteine that could be targeted for modification. Hence, we have introduced the Ser-32 to Cys (S32C) mutation of hMT-1b into hMT-2 and examined the properties of the protein expressed. This derivative, indeed, contains a free cysteine, which can be labeled specifically with a second fluorescent probe. In the resultant double-labeled protein, the fluorophores are at a distance that can generate FRET. Because of the specific location of the fluorophores, the FRET sensor monitors metal binding and conformational changes of the N-terminal β-domain of MT, the more reactive of the two toward EDTA (4) or 5,5′-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB) (5), in transfer of its zinc atoms to a zinc-dependent enzyme (6), or in its reactivity with S-nitroso-l-cysteine or hydrogen peroxide (7).

Materials and Methods

Materials.

Restriction enzymes were from Promega and New England Biolabs; ampicillin, isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), CdCl2, Ellman's reagent (DTNB), 2,2′-dithiodipyridine, DTT, and subtilisin Carlsberg were from Sigma; pTYB11 vector, intein forward primer, ER2566 cells, and chitin resin as part of the IMPACT system were from New England Biolabs; and Alexa Fluor 488 carboxylic acid, succinimidyl ester, dilithium salt [Alexa-488, a fluorescein derivative (F)], and Alexa Fluor 546 C5 maleimide [Alexa 546, a rhodamine derivative (R)] were from Molecular Probes.

Site-Directed Mutagenesis.

MT cDNA was subcloned into the vector pKF-19k (8) to be used as a template for constructing the S32C mutant. Mutagenesis was performed by the oligonucleotide-directed dual amber-long and accurate PCR method (Mutant-Super Express Km kit, Takara Shuzo, Kyoto). pKF-19k-MT has a dual amber stop mutation at the kanamycin (Km)-resistance gene (aminoglucoside 3′-phosphotransferase) at the 151st and 153rd codons for Gln, resulting in loss of the Kmr phenotype. The phenotype can be recovered by a suppressor produced from the genome of a host cell such as JM109, translating the amber stop codon to Gln. However, this amber mutation cannot be recovered in suppressor-free (sup0) host cells such as MV1184 cells. Thus, in these cells, the Kmr phenotype can be recovered only by site-directed mutagenesis when this stop codon is changed to Gln (TAG to CAG, selection primer). Together with this primer, the other primer (mutant primer) is designed for site-directed mutagenesis of the target gene (in this case hMT-II, S32C mutant) for the same PCR. The mutant primer sequence for the S32C mutant is as follows: 5′-TGT ACT AGT TGC AAG AAA TGT TGC TGT TCC TGC-3′ (mismatched codon is underlined). The selection primer sequence is as follows: 5′-GA CTG CGC CTG AGC GAG ACG- 3′ (amber stop codons are underlined). The PCR product from the two primers (mutant primer-selection primer) is then used to prime the next PCR to generate mutant pKF-19k-MT (S32C). The final PCR products were extracted from agarose gels and transformed into MV1184 cells. Mutant clones containing the S32C mutant gene were selected by the recovered Kmr phenotype in the sup0 host cells. The mutant MT plasmid was purified, excised, and ligated into the pTYB11 expression vector (2). The DNA sequence of the mutant MT was confirmed with the intein forward primer (New England Biolabs) at the molecular biology core facilities of the Dana–Farber Cancer Institute (Boston).

Overexpression and Purification of MT.

The plasmids encoding the MT gene (human, isoform 2) of the WT and the S32C mutant were transformed into Escherichia coli ER2566. MT protein was prepared by using the IMPACT T7 system (New England Biolabs; ref. 9). In this system, the intein-MT fusion protein is recovered by absorption on an affinity resin. T (thionein, apoform of MT) is cleaved from the absorbed fusion protein by DTT-mediated proteolysis and eluted together with the N-terminally cleaved maltose-binding peptide. Both are separated by gel filtration (Sephadex G-25, equilibrated with 10 mM HCl, pH 2) after acidification to pH 1 with HCl. The pooled T fractions were reconstituted with CdCl2, adjusted to pH 8.6 with Tris base to stabilize the metal clusters, lyophilized, and separated from free metal ions by gel filtration (Sephadex G-50, equilibrated with 20 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.4). MT was quantified by determination of thiols (ɛ343 = 7,600 M−1⋅cm−1) with 2,2′-dithiodipyridine (10) and metals by atomic absorption spectrophotometry (Perkin–Elmer Model 2280).

Thiol Reactivity of MT Toward DTNB and Thiol Quantification.

Thiol reactivity of MTs was determined with DTNB under pseudofirst order rate conditions with regard to the 20 thiols in MT (11). The reaction between MT (1 μM) and DTNB (0.1 μM) in 20 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.4, was followed spectrophotometrically at 412 nm and 25°C. Thiol groups were determined from the amount of 2-nitro-5-thiobenzoate (ɛ412 = 14,150 M−1⋅cm−1) formed after the reaction with 10 mM DTNB.

Circular Dichroism (CD).

Purified MT proteins were analyzed by CD spectroscopy (Jasco Model J-715 CD spectrometer) at 25°C. CD is expressed as molar ellipticity, [θ] (deg cm2·dmol−1).

N-Labeling of MT.

Purified WT MT containing only cadmium (CdMT) was washed with degassed 20 mM Hepes·NaOH, pH 7.4, and concentrated to 1 mg/ml by using a Centricon microconcentrator (Amicon). CdMT (975 μg, 150 nmol) was diluted with 20 mM Hepes·NaOH, pH 7.4, to 3.26 ml and incubated with 1 mg (1,550 nmol, i.e., to a final molar ratio of 10:1) of the amine-reactive probe Alexa 488 succinimidyl ester (a fluorescein derivative referred to as F), for 1 h at 25°C with stirring in the dark. Labeled protein was separated from the free probe by Sephadex G-50 gel filtration (1 × 50 cm and equilibrated with the same degassed buffer). The stoichiometry of labeling was determined from a molar absorptivity of ɛ494 = 71,100 M−1⋅cm−1 for Alexa 488, and both thiol and metal determinations for MT.

S-Labeling of MT.

The free cysteine in the S32C CdMT mutant was labeled at pH 7.4 instead of 8.6 (see Overexpression and Purification of MT) immediately after the purification of T and its reconstitution with metal ions. Reconstituted MT (4.34 mg, 668 nmol) was added to 1 mg (967 nmol, i.e., a final molar ratio of 1.5:1) of the thiol-reactive probe Alexa 546 maleimide (a rhodamine derivative referred to as R) dissolved in 500 μl of DMSO, and incubated for 2 h with stirring under nitrogen to prevent MT oxidation. Labeled protein was separated from the free probe by gel filtration as described above. The stoichiometry of labeling was determined from a molar absorptivity of ɛ554 = 111,100 M−1⋅cm−1 for Alexa 546, and both thiol and metal determinations for MT.

Dual Labeling of S32C MT.

Dual labeling of the S32C CdMT mutant was performed by labeling the free cysteine first as described above. The S-labeled mutant in Tris buffer was brought to 20 mM Hepes·NaOH, pH 7.4, and free metals and free probe were removed by multiple dilution/concentration cycles with a Centricon microconcentrator. After removing a precipitate by centrifugation, the mutant was labeled at the N terminus as described above. The labeling ratios for the S32C mutant were calculated by quantification of each probe in donor/acceptor (F/R)-MT (see above).

Fluorescence Spectroscopy of the Dual-Labeled Protein.

Labeled proteins were characterized by fluorescence spectroscopy with a FluoroMax-2 fluorimeter (Instruments SA, Edison, NJ). Excitation wavelengths of 460 and 530 nm were used for Alexa 488 and Alexa 546, respectively.

Cadmium Release from Cd7MT by EDTA.

MT loses its bound metal ions when incubated with EDTA (12). CdMT (100 nM) was incubated with EDTA (300 nM) and NaCl (50 μM) in 20 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.4, at 25°C. The UV absorption at 254 nm is proportional to bound cadmium (13). Hence, the metal content of the protein can be monitored directly by spectrophotometric readings at this wavelength and expressed as Cd/MT with a molar absorptivity of ɛ254 = 1.05 × 106 M−1⋅cm−1. F/R-labeled MT (1 nM) was also incubated with EDTA (3 μM) and NaCl (500 μM) for 8 h (14) and the reactions were studied.

Proteolysis of Dual-Labeled Cd7MT.

Dual-labeled Cd7MT was treated with subtilisin under conditions that produce the individual domains from the whole molecule (15). For this purpose, 300 μl of Cd7MT (250 nM) was incubated with 1 μl of subtilisin (1 μg/μl in MilliQ water) for 24 h at room temperature.

Replacement of Cadmium in Dual-Labeled Cd7MT with Zinc.

Dual-labeled Zn7MT was prepared by subsituting zinc for cadmium in Cd7MT. Dual-labeled Cd7MT (120 μg) was diluted to 2 ml (9.2 μM) with 100 mM zinc acetate, pH 6.5, and concentrated to 100 μl in a Centricon microconcentrator, and this step was repeated nine times until cadmium ions were exchanged completely. At each step, the amount of cadmium remaining in the dual-labeled MT was measured by atomic absorption spectrophotometry in the filtrate. Dual-labeled MT containing only zinc (ZnMT) was recovered by gel filtration.

Distance Calculations from FRET Experiments.

Distances were calculated from E = R06/(R06 + R6), where E is the efficiency of energy transfer, R0 is the Förster radius corresponding to 50% energy transfer efficiency, and R is the distance between the donor and the acceptor. The efficiency is expressed as percent quenching of the donor emission obtained from the area of the donor emission band.

Results

Selection of Reactive Groups in hMT-2 for Fluorescence Labeling.

The design of a protein FRET sensor typically involves specific introduction of fluorescent donor and acceptor probes on cysteine and lysine side chains. In MT, only lysine residues are available for amine modification, but because there are eight of them, differential labeling would yield ambiguous answers. However, recombinant MT expressed in the IMPACT T7 system (2) has a free N terminus that can be targeted specifically by varying the pH of the modification reaction as the amino group at the N terminus has a lower pKa value compared with that of the lysine side chain. A search of the MT sequence database revealed that human MT-1b contains an additional cysteine at position 32 between the two domains carrying the clusters where a second fluorophore could be attached (3). When it is combined with a probe attached at the N terminus, this cysteine is positioned nearly ideally at the other end of the β-domain to be tagged with a second fluorescent probe chosen to result in an energy donor/acceptor pair. The properties of the hMT-1b protein, however, were unknown, in particular whether the extra cysteine participates in the formation of the metal/thiolate clusters. To address this question, we introduced the S32C mutation into hMT-2 and studied the properties of the protein expressed.

Mutagenesis and Characterization of S32C CdMT.

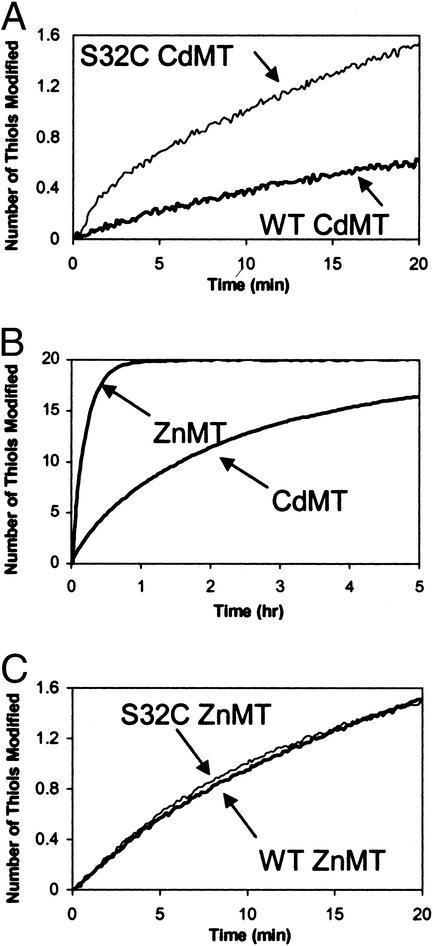

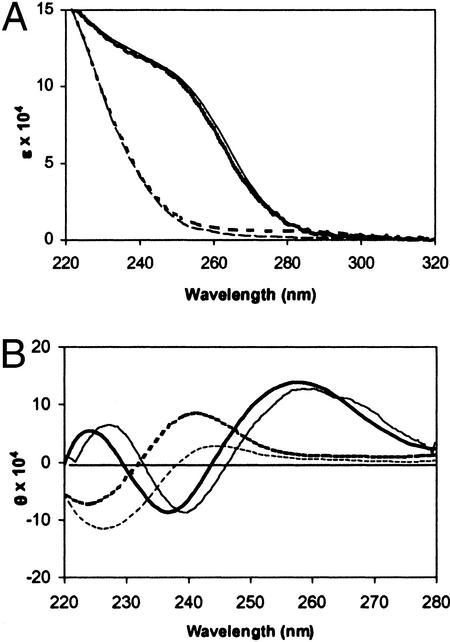

The S32C mutant was characterized with regard to its metal binding, metal cluster reactivity, and overall conformation. It binds seven cadmium or zinc atoms per molecule of protein. Assays with 2,2′-dithiodipyridine demonstrate that it contains 21 thiol groups, whereas the WT contains only 20. The biphasic reaction of S32C CdMT demonstrates that this mutant has one thiol group whose reactivity is higher than that of the others (Fig. 1A). This thiol likely is a free thiol, because WT CdMT does not exhibit such a reactive thiol (Fig. 1A). The cysteines in the clusters of CdMT are generally less reactive than those in the clusters of ZnMT (Fig. 1B), giving rise to a greater differential reactivity of the additional cysteine in the CdMT mutant (Fig. 1A) when compared with the ZnMT mutant (Fig. 1C). Therefore, CdMT was chosen for modification of the free cysteine. UV spectra (Fig. 2A) of the mutant ZnMT and CdMT are identical to those of the recombinant WT proteins (2). CD spectra (Fig. 2B) of the mutant protein differ only slightly from those of recombinant WT proteins. These results indicate that the additional cysteine in the S32C mutant does not participate in the clusters, which essentially retain their structures.

Figure 1.

Thiol reactivity of MT toward different concentrations of Ellman's reagent (DTNB). (A and C) Reactivity of MT with DTNB when [DTNB] ≈ [MT]. WT or S32C mutant of CdMT (A) or ZnMT (C) (0.1 μM) was incubated with DTNB (1 μM). The reactions were studied in 20 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.4, and followed spectrophotometrically at 412 nm at 25°C. (B) Reactivity of MT with DTNB when [DTNB] ≫ [MT]. Reaction of WT ZnMT (1 μM) or CdMT (1 μM) with DTNB (10 mM).

Figure 2.

UV (A) and CD (B) spectra of zinc (dashed lines)- or cadmium (solid lines)-bound forms of recombinant WT (thin lines) or S32C mutant MT (thick lines). Spectra were recorded with 6 μM MT in 20 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.4, at 25°C.

Single and Dual Site-Specific Fluorescence Labeling of WT and S32C CdMT.

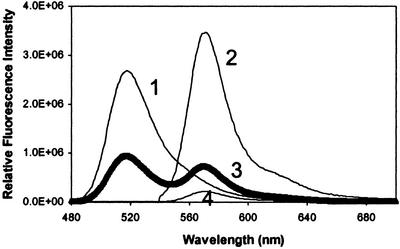

In the IMPACT T7 expression system, the target protein (hMT-2) is fused to the C terminus of the intein fusion protein and MT is generated with a free N terminus after DTT-mediated proteolysis (2). This procedure makes it possible to label the N terminus with an amine-specific fluorophore. WT MT was labeled specifically at the N terminus with Alexa 488 succinimidyl ester at a molar ratio of 1.09 (the result of three independent experiments). To avoid labeling other amine groups such as lysine with a higher pKa (10.79), a pH value of 7.4 was selected for labeling. MT labeled at the N terminus fluoresces maximally at 519 nm when excited at 460 nm (Fig. 3, line 1).

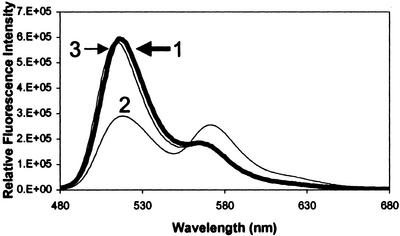

Figure 3.

Fluorescence emission spectra of N- (line 1), S- (lines 2 and 4), or dual-labeled (line 3) MT. Shown are spectra of WT F-MT (1 μM) excited at 460 nm (line 1) and S32C mutant R-MT (1 μM) excited at 530 nm (line 2) or 460 nm (line 4). Single-labeled MTs showed maximum emission at 519 nm (Alexa 488) and 573 nm (Alexa 546), respectively. The S32C F/R-MT (1 μM) was excited at 460 nm (line 3) or 530 nm (overlapping with line 2), respectively, to monitor energy transfer between donor (F) and acceptor (R). When the F/R-labeled protein was excited at 530 nm (overlapping with line 2) the emission spectrum of the acceptor (rhodamine) was obtained.

The S32C mutant was labeled at the free cysteine residue with Alexa 546 maleimide. The molar ratio of probe to protein was 1.0 (the result of three independent experiments). The labeled S32C mutant emits maximally at 573 nm when excited at 530 nm (Fig. 3, line 2).

Because of the reactivity of thiols with amine-specific reagents, dual labeling was performed by first S-labeling, then N-labeling. This procedure introduced two probes into the molecule, both with 1:1 labeling stoichiometries (the result of three independent experiments). In the labeled protein, seven cadmium atoms per molecule of MT remained bound.

FRET of Dual-Labeled MT.

Emission spectra of dual-labeled MT were recorded under the same conditions used for the single-labeled proteins. When F/R-MT is excited at the donor absorbance wavelength (460 nm), the emission peaks are at 519 and 573 nm (Fig. 3, line 3). In dual-labeled F/R-MT, the donor emission at 519 nm decreases 65% and the acceptor emission at 573 nm increases relative to the emission spectra of the single-labeled MTs (line 1). Because emission at 573 nm is typical for the acceptor, this experiment demonstrates energy transfer between the two fluorophores. When single-labeled R-MT was excited at 460 nm (line 4), the emission at 573 nm was significantly less than that of the dual-labeled protein (line 3 vs. line 4). These experiments clearly demonstrate that the two probes labeling the β-domain are properly spaced to allow energy transfer.

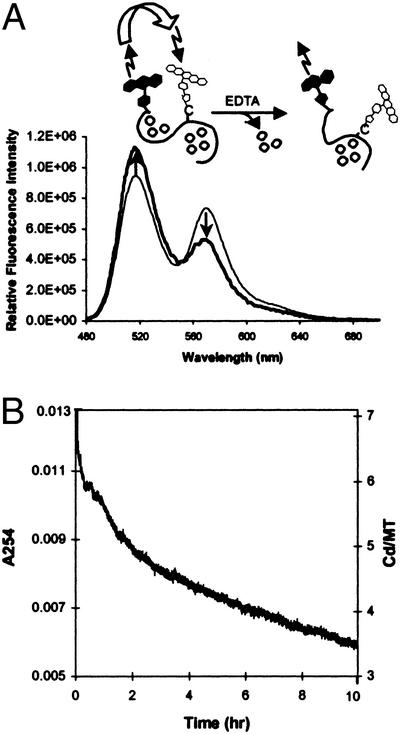

The possibility that energy transfer between the two fluorescent probes is affected by metal release resulting in structural changes in the β-domain was tested by incubating F/R-MT with EDTA and NaCl for 8 h. Energy transfer from donor (F) to acceptor (R) indeed decreases (Fig. 4A): the ratio between the emission peaks of acceptor and donor (573/519 nm) changes from 0.8 to 0.5. To ascertain whether these changes are because of release of cadmium, metal release from MT was monitored spectrophotometrically under the same conditions. Cd7MT releases exactly three cadmium atoms when treated with EDTA for 8 h (Fig. 4B). These metals originate from the β-domain, which has been shown to interact preferentially with EDTA (4, 12). Thus, the observed changes in energy transfer are caused by metal release from the β-cluster of the FRET sensor.

Figure 4.

(A) Change of FRET in F/R-CdMT on metal release. The S32C mutant MT (1 μM) was incubated with EDTA (3 μM) and NaCl (500 μM) for 8 h at 25°C (thick line). The acceptor emission decreases with a concomitant increase of the donor emission compared with the control (thin line). The drawing illustrates change of energy transfer between the fluorescein donor (filled symbols) and rhodamine acceptor (open symbols) and concomitant metal release (open circles) from the β-domain. (B) Release of cadmium from Cd7MT on treatment with EDTA. Cd7MT (100 nM) was incubated with EDTA (300 nM) and NaCl (50 μM) at 25°C. The reaction was monitored at 254 nm for 8 h and the number of cadmium ions bound to MT was calculated.

Proteolysis of Dual-Labeled Cd7MT.

Only a relatively small decrease of FRET is observed under conditions where the metal atoms in the β-cluster are released (Fig. 4A). Therefore, we searched for conditions that abolish FRET. The individual domains of MT can be generated by proteolysis of CdMT with subtilisin (15). Cleavage occurs between residues 30 and 31, i.e., between the two lysines in the hinge region. Thus, this treatment will cleave the polypeptide chain between the fluorophores. After incubation with subtilisin, energy transfer of dual-labeled MT (Fig. 5, line 1) decreases significantly compared with the control sample (Fig. 5, line 2). The emission spectrum of a mixture of the two free fluorophores is similar to that of cleaved MT (Fig. 5, line 3), except for a slight 2-nm shift relative to the emission maximum of the donor. This result indicates that treatment with subtilisin completely eliminates energy transfer in MT.

Figure 5.

Effect of subtilisin on FRET of F/R-CdMT. F/R-CdMT (1 μM, line 2) was treated with subtilisin for 24 h (line 1). Subtilisin-treated MT or the free fluorophores were excited at 460 nm. A comparison between the emission spectra of subtilisin-treated MT and those of the free fluorophores (1 μM, line 3) shows that energy transfer between donor and acceptor is abolished.

The observation that the metal-free protein shows FRET, but the cleaved β-domain does not, shows that the apo-β-domain is not in a random coil conformation after metal release. Titrations with DTNB before and after release of cadmium with EDTA give no evidence for the formation of disulfides. Denaturing agents such as SDS (0.5% wt/vol) or guanidine hydrochloride (6 M) decrease FRET to a much larger extent than metal release, i.e., 80%, clearly demonstrating that the apo-β-domain maintains some of its tertiary structure after metal release and that the FRET sensor measures conformational changes in addition to the changes elicited by metal release. Jointly, these experiments demonstrate that the FRET sensor measures both metal binding and conformational effects in the absence of metals.

Replacement of Cd in F/R-CdMT with Zn.

Normally, the conversion of CdMT to ZnMT can be accomplished by the removal of cadmium at low pH, neutralization, and reconstitution with zinc ions. However, because of the chemical instability of the fluorescein fluorophore at low pH, we had to devise a reverse-replacement procedure in which zinc displaces cadmium against a thermodynamic gradient of almost four orders of magnitude. Nine washes with excess zinc in Centricon microconcentrators were required to completely remove cadmium from F/R-CdMT. The emission spectrum of dual-labeled ZnMT obtained after removing excess zinc ions by gel filtration is virtually identical to that of dual-labeled CdMT.

Discussion

The results we obtained demonstrate that S32C MT has the same overall structure as MT; furthermore the composition of the clusters with regard to zinc or cadmium and the overall metal binding capacity are virtually identical. A small red-shift (<5 nm) between the CD spectra of WT and S32C mutant MT (Fig. 2B) is likely caused by the replacement of the rather strictly conserved Ser-32, which is involved in hydrogen-bonding interactions with the main-chain carbonyls of Cys-34 and Cys-38 (16) in the α-domain, by Cys, which, if at all, interacts more weakly. Chiroptical features are the most sensitive parameters of the structure of the cadmium/thiolate clusters (17). The distance between the oxygen in the side chain of Ser-32 and any of the metal atoms in the α-cluster is at least 5 Å. These relatively large distances are further reason to believe that Cys-32 does not participate in metal binding in the clusters of either the mutant or hMT-1b.

The S32C CdMT can be specifically labeled with two different fluorescent probes between which energy transfer occurs. Once labeled, CdMT can be transformed into ZnMT for functional studies of the zinc protein. While CdMT readily forms when cadmium ions are added to ZnMT, the reverse is not the case because of the large difference in binding constants between ZnMT and CdMT (Kd, CdMT = 2 × 10−16 M and Kd, ZnMT = 2 × 10−12 M; ref. 18). Also, it was not possible to prepare ZnMT from labeled CdMT by means of a route involving both acidification of the protein to pH <2 to remove cadmium and reconstitution of the apoprotein (thionein) with zinc, because the fluorophore is not stable at low pH. The problem was solved, however, by employing a reverse-replacement procedure, in which a large excess of zinc displaces cadmium against the thermodynamic gradient, aided by a slightly lowered pH. Another potential approach for metal replacement could involve labeling of CdMT with a pH-stable fluorophore such as 4-([4-(dimethylamino)phenyl]azo)benzoic acid (Dabcyl) (19), and preparing ZnMT by means of the acidification and reconstitution procedure.

When compared with a construct containing GFP mutants fused to both termini of MT (14), the MT FRET probe has several advantages. First and foremost, this probe is designed to monitor the conformation of the β-domain, which is the more reactive of the two in zinc-transfer experiments (5, 7), and it is the only one with biological activity in modulating mitochondrial respiration (20). Thus, the probe can be used to study metal binding of a single domain of MT. Second, the sensor with small molecules attached is much more likely to resemble the native state of MT than a fusion protein carrying two bulky proteins at each terminus. Thus, studies of metal binding to the MT-GFP FRET probe maybe confounded by metal binding to the GFPs. The number of metals bound and released from the MT-GFP FRET probe was not reported (14). In contrast, the metal content of the MT FRET probe is known.

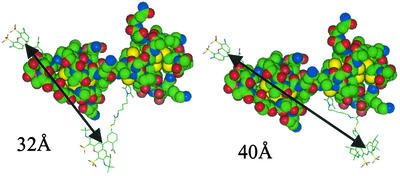

FRET experiments demonstrate that the MT FRET probe is responsive to the metal content of the protein as well as to environmental factors that affect the structure of the apo-β-domain. Under conditions where the clusters of MT release cadmium (Fig. 4B) (14, 21), the ratio of emission peaks (573/519 nm) changes from 0.8 to 0.5 (Fig. 4A). This change is qualitatively similar to the change from 1.8 to 1.1 in the MT-GFP FRET probe (14), although the MT FRET sensor detects metal release from only one of two domains. The calculated distance of 50 Å between the probes, based on the donor emission spectra (Fig. 3) and the known R0 value for the rhodamine/fluorescein pair of 56 Å (22), is longer than the calculated distance of 23 Å between the N-terminal amino group and the oxygen of Ser-32 in the crystal structure of MT (23). This apparent discrepancy could be explained in several different ways: The actual distance between the probes in MT in solution might be longer than that measured in crystals. NMR studies (23) revealed that the N terminus of MT (segment 1–12) is very flexible, thus likely increasing the distance. Further, the orientation of the two domains relative to one another is known only from the crystal structure. The mobility of the domains relative to the linker region in solution adds additional uncertainty to the estimate of the distance between the probes. Last but not least, the probes have molecular sizes of 10–15 Å. In a structural model of MT with the probes attached (Fig. 6) distances of 32–40 Å between the probes are longer than that between the two amino acids. The additional variations of the distance of up to 10 Å result from the flexibility of the hydrocarbon tail of Alexa 546. All of these factors could lead to an actual distance that is close to that which was measured, particularly because the two amino acid side chains to which the probes are attached point in different directions. A donor/acceptor pair with a smaller R0 value would yield more accurate distance calculations if the distance were indeed <56 Å. In the apo-β-domain, the distance between donor and acceptor remains close enough to permit energy transfer, however. Hence, the apo-β-domain exists in a structure where such energy transfer is possible. The distance between the probes after metal release from the β-domain changes only slightly, i.e., from 50 to 52.3 Å (E = 0.6). Detailed studies on the kinetics of metal binding with this FRET probe will provide information on the individual steps in the formation and disassembly of the cluster.

Figure 6.

Structure modeling of F/R-MT. Structures of F/R probes were generated by using CHEMDRAW and energy-minimized in CHEM3D (both from CambridgeSoft, Cambridge, MA). Three-dimensional probe structures were imported into INSIGHT II (Accelrys, San Diego) and manually attached at the appropriate amino acid side chains. Ser-32 was mutated to Cys by using the Biopolymer module in INSIGHT II. To estimate the range of distances between the attached probes, flexibility was allowed within the R probe where torsions are possible. The modeling revealed a 32- to 40-Å separation between the probes when allowing for different conformations of the R probe without interactions with the MT structure.

The β-domain FRET probe exhibits many potential applications as a nanosensor for detection of biologically essential (zinc) and toxic (cadmium) metal atoms. Fluorescent probes for zinc have detection limits in the nanomolar range (24). The MT-FRET sensor has a detection limit in the picomolar range, and therefore can serve as a biosensor for detecting cellular “free” zinc in the physiological range of picomolar concentrations (25, 26). The development of Ca2+-sensing probes provides a paradigm for the application of such sensors (27).

In addition, the MT FRET sensor can be used as a redox sensor. The thiolate ligands of zinc in MT confer redox activity on the clusters (28). Because the metal content of the protein depends on the redox environment, metal-dependent conformational changes detected by FRET also are redox-dependent. When MT is oxidized by a catalyst (selenium) and glutathione disulfide (GSSG) it loses its zinc (29). Vice versa, in the presence of a selenium catalyst glutathione (GSH) reduces the oxidized protein. Thus, the MT FRET sensor might be suitable for the measurement of the glutathione redox state, a major biological redox buffer (30), and further might be applicable to measurements in specific cellular compartments such as in liver mitochondria, where MT is located in the intermembrane space (20). GSH/GSSG ratios differ in cellular compartments and vary from 40 to 100 in the cytosol and from 1 to 3 in the endoplasmic reticulum (31). Redox sensing is not restricted to the GSH/GSSG pair, however, as the MT-GFP FRET probe has already been used to measure specific oxidants such as nitric oxide (14).

In vivo studies employing the MT FRET sensor obviate some of the problems encountered with GFP fusion proteins. Generally, FRET sensors with GFP protein mutants transfected into cells are excellent tools for the visualization of target molecules in living cells. Genetic engineering techniques using diverse GFP fluorophores with different emission wavelengths create “chameleons” that change their colors dependent on changes in conformation (27). This attractive technology has its limitations, however. The bulky GFPs (27 kDa) can affect the behavior of their target protein. Nonspecific binding of substrates to GFPs is a major concern, and therefore the phenomena observed with these constructs are prone to yield artifacts. The MT FRET sensor does not have this limitation as it is specifically labeled with small fluorophores (0.6 kDa), which would be easily used for fluorimetric analysis based on the FRET principle (32).

Other limitations of MT GFP fusion proteins are the effects that their overexpression in the host cell may have. Overexpressed MT is usually not saturated with metals because of limited zinc supply (33). Thus, overexpression of the MT-GFP FRET probe affects the zinc pool and likely the redox potential in host cells (34). In contrast, when using the MT FRET sensor, either MT FRET or T FRET could be introduced into the cell and, therefore, a better control of the parameters to be sensed can be exercised. Before these applications can be explored and the FRET signals in vivo interpreted, it is necessary to dissect effects of metal binding and other conformational effects that influence the molecule (ligand binding, oxidation state). The MT FRET sensor allows for the accomplishment of this dissection because its metal content can be measured precisely.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Gordon G. Hammes for advice and helpful discussions, Dr. Richard B. Thompson for helpful discussions, Dr. Jack Liang for the use of his CD spectrometer, and Dr. Jeremy Jenkins for help in modeling the structure of F/R-MT. This work was supported by the Endowment for Research in Human Biology and National Institutes of Health Grant GM 065388 (to W.M.).

Abbreviations

- DTNB

5,5′-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid)

- FRET

fluorescence resonance energy transfer

- MT

metallothionein

- T

thionein (apoform of MT)

- hMT

human MT

- CdMT or ZnMT

MT containing only cadmium or zinc

- S32C

a mutant of recombinant MT containing a Cys residue at position 32 of the MT sequence

- (F/R)-MT

donor/acceptor-MT, labeled with Alexa 488 succinimidyl ester (fluorescein derivative) and Alexa 546 maleimide (rhodamine derivative)

References

- 1.Yang Y, Maret W, Vallee B L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:5556–5559. doi: 10.1073/pnas.101123298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hong S-H, Toyama M, Maret W, Murooka Y. Protein Expression Purif. 2001;21:243–250. doi: 10.1006/prep.2000.1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heguy A, West A, Richards R I, Karin M. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6:2149–2157. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.6.2149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vazquez F, Vašák M. Biochem J. 1988;253:611–614. doi: 10.1042/bj2530611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jiang L-J, Vašák M, Vallee B L, Maret W. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:2503–2508. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.6.2503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jiang L-J, Maret W, Vallee B L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:3483–3488. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen Y, Irie Y, Keung W M, Maret W. Biochemistry. 2002;41:8360–8367. doi: 10.1021/bi020030+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hashimoto-Gotoh T, Yasojima K, Tsujimura A. Gene. 1995;167:333–334. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00705-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chong S, Montell G E, Zhang A, Cantor E J, Liao W, Xu M-Q, Benner J. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:5109–5115. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.22.5109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pedersen A O, Jacobsen J. Eur J Biochem. 1980;106:291–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1980.tb06022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Savas M M, Petering D H, Shaw C F., III Inorg Chem. 1991;30:581–583. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gan T, Munoz A, Shaw C F, III, Petering D H. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:5339–5345. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.10.5339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kägi J H R, Vallee B L. J Biol Chem. 1961;236:2435–2442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pearce L L, Gandley R E, Han W, Wasserloos K, Stitt M, Kanai A J, McLaughlin M K, Pitt B R, Levitan E S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:477–482. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.1.477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nielson K B, Winge D R. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:4941–4946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robbins A H, McRee D E, Williamson M, Collett S A, Xuong N H, Furey W F, Wang B C, Stout C D. J Mol Biol. 1991;221:1269–1293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Willner H, Vašák M, Kägi J H R. Biochemistry. 1987;26:6287–6292. doi: 10.1021/bi00393a049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kägi J H R, Schäffer A. Biochemistry. 1988;27:8509–8515. doi: 10.1021/bi00423a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park C, Kelemen B R, Klink T A, Sweeney R Y, Behlke M A, Eubanks S R, Raines R T. Methods Enzymol. 2001;341:81–94. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(01)41146-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ye B, Maret W, Vallee B L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:2317–2322. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041619198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Winge D R, Miklossy K-A. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:3471–3476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gohlke C, Murchie A I, Lilley D M, Clegg R M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:11660–11664. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.24.11660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wüthrich K. Methods Enzymol. 1991;205:502–520. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)05135-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hirano T, Kikuchi K, Urano Y, Nagano T. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:6555–6562. doi: 10.1021/ja025567p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peck E J, Jr, Ray W J., Jr J Biol Chem. 1971;246:1160–1167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simons T J B. J Membr Biol. 1991;123:63–71. doi: 10.1007/BF01993964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miyawaki A, Llopis J, Heim R, McCaffery M J, Adams J A, Ikura M, Tsien R Y. Nature. 1997;388:882–887. doi: 10.1038/42264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maret W, Vallee B L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:3478–3482. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen Y, Maret W. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:3346–3353. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.02250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meister A. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:17205–17208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hwang C, Sinskey A J, Lodish H F. Science. 1992;257:1496–1502. doi: 10.1126/science.1523409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Auld D S. In: Proteolytic Enzymes: Tools and Targets. Sterchi E E, Stöcker W, editors. Heidelberg: Springer; 1999. pp. 30–48. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hong S-H, Gohya M, Ono H, Murakami H, Yamashita M, Hirayama N, Murooka Y. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2000;54:84–89. doi: 10.1007/s002530000360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.St. Croix C M, Wasserloos K J, Dineley K E, Reynolds I J, Levitan E S, Pitt B R. Am J Physiol. 2002;282:L185–L192. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00267.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]