Abstract

The C-terminal domain (CTD) of the largest subunit of RNA polymerase II (RNAPII) is heavily phosphorylated during the transition from transcription initiation to the establishment of an elongation-competent transcription complex. FCP1 is the only phosphatase known to be specific for the CTD of the largest subunit of RNAPII, and its activity is believed to be required to reactivate RNAPII, so that RNAPII can enter another round of transcription. We demonstrate that FCP1 is a phosphoprotein, and that phosphorylation regulates FCP1 activities. FCP1 is phosphorylated at multiple sites in vivo. The CTD phosphatase activity of phosphorylated FCP1 is stimulated by TFIIF, whereas dephosphorylated FCP1 is not. In addition to its role in the recycling of RNAPII, FCP1 also affects transcription elongation. Phosphorylated FCP1 is more active in stimulating transcription elongation than the dephosphorylated form of FCP1. We found that only phosphorylated FCP1 can physically interact with TFIIF. We set out to purify an FCP1 kinase from HeLa cells and identified casein kinase 2, which, surprisingly, displayed a negative effect on FCP1-associated activities.

Numerous studies have extensively documented the effects of phosphorylation on the transcriptional properties of RNA polymerase II (RNAPII) (1–5). The target of these regulatory phosphorylation events is the C-terminal domain (CTD) of the largest subunit of RNAPII. The hypophosphorylated form of RNAPII, designated RNAPIIA, was demonstrated to be essential for preinitiation complex formation and transcription initiation, whereas hyperphosphorylated RNAPII, designated RNAPIIO, is involved in transcription elongation (6, 7). During the transition from transcription initiation to elongation, the CTD of the largest subunit of the RNAPII is heavily phosphorylated at Ser-2 and Ser-5 within the multiply repeated consensus sequence YS2PTS5PS (2, 4, 8). The CTD of the mammalian protein contains 52 repeats, which are phosphorylated by a number of different protein kinases, including CDK7 (5, 9), CDK9 (10, 11), and CDK8 (3, 12). The CDK7 and CDK9 kinases are tightly linked to the transcription cycle. In contrast, the kinase activity of CDK8, a component of the Mediator complex, was shown to negatively regulate transcription initiation.

Although multiple kinases target the CTD of RNAPII, the only protein phosphatase known to dephosphorylate the CTD is FCP1. FCP1 was identified in both mammalian cells (13–15) and Saccharomyces cerevisiae (16, 17). Dephosphorylation of the CTD of the largest subunit of RNAPII by FCP1 can facilitate recycling of the hyperphosphorylated form of RNAPII, allowing RNAPII to enter another round of transcription (15). FCP1 dephosphorylates the CTD of the largest subunit of RNAPII in solution (14–16, 18–20) and when associated with transcription elongation complexes (15, 21, 22). The phosphatase activity of FCP1 is stimulated by the general transcription factor TFIIF; however, TFIIB inhibits this stimulation (14). Mapping of the interaction domains between FCP1, TFIIF, and TFIIB revealed that the C terminus of FCP1 mediated the interaction with both general transcription factors (17–19). Therefore, TFIIF and TFIIB compete for binding to the same region of FCP1.

In addition to its CTD phosphatase activity, FCP1 also plays an important role in transcription elongation (15, 19, 23–25). FCP1 was found to genetically interact in yeast with the cyclin-dependent kinases Bur1/Bur2 (26, 27) and CTK1/CTK2/CTK3 (10, 28), both of which appear to be related to the mammalian elongation factor P-TEFb (2, 11, 29). FCP1 was identified in different complexes together with RNAPII and TFIIF (18, 30), and in Schizosaccharomyces pombe, a direct interaction between FCP1 and the Rpb4 subunit of RNAPII was demonstrated (30).

Interestingly, recent studies showed that CTD dephosphorylation in early Xenopus laevis embryos occurs in the absence of transcription (20). Experiments in yeast showed that inactivation of the FCP1 catalytic activity had a negative impact on general transcription in vivo (23).

Taken together, the regulation of FCP1 functions appears complex. In the present study, we demonstrate that human FCP1 is a phosphoprotein, and that the activities associated with FCP1 are regulated by phosphorylation.

Materials and Methods

Purification of Baculovirus-Expressed FCP1.

Recombinant human FCP1 was expressed as a C-terminal histidine-tagged fusion protein in baculovirus-infected insect cells, as described previously (23). FCP1 was further purified on a DE52 (Whatman) column.

Dephosphorylation of FCP1 with Alkaline Phosphatase (AP).

FCP1 purified from baculovirus-infected SF9 cells was incubated either without (mock) or in the presence of AP (20 units/μl; Roche Diagnostic) in BC100 for 2.5 h at 30°C. Mock- and AP-treated FCP1 were separated from AP by using a DE52 (Whatman) column. AP appeared in the flow-through and BC100 wash fractions, whereas FCP1 was eluted with BC350.

CTD Phosphatase Assays.

Reactions were performed in a total volume of 30 μl in buffer P (20 mM Hepes, pH 7.9/10 mM MgCl2/10% glycerol/1 mM DTT/0.2 mM PMSF) in the presence of 60 mM KCl and 80 ng/μl BSA. CTD phosphatase reactions contained 0.1–32 fmol of FCP1 and 0.25 pmol of purified RNAPIIO from HeLa cells (7) as substrate. As indicated, 0.65 pmol of recombinant human TFIIF (31) was added to the assay. Reactions were incubated for 22 min at 30°C, stopped by the addition of SDS loading buffer, and resolved on a 6% SDS polyacrylamide gel.

Transcription Elongation Assays.

Transcription reactions were performed with purified basal transcription factors (31), baculovirus-expressed recombinant human FCP1, and the immobilized DNA template pML20–47 (32). A detailed description of the procedure can be found in Supporting Text, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site (www.pnas.org).

Immunoprecipitation and Western Blot Analysis.

Mouse monoclonal antibodies against FCP1 were bound to protein G-agarose beads (Roche). After preincubation of FCP1 and TFIIF for 30 min on ice, the beads with the attached antibody were added, and the mixture was further incubated for 4.5 h at 4°C. Immunocomplexes were washed with BC250 containing 0.05% Nonidet P-40 (vol/vol) and BC100. Protein complexes were removed from the beads by the addition of SDS loading buffer and analyzed on a 6% SDS polyacrylamide gel.

Kinase Assays.

Kinase assays were performed in a total volume of 50 μl in buffer K (20 mM Hepes, pH 7.9/10 mM MgCl2/1 mM DTT) containing 60 mM KCl, 60 μM ATP, 30 nCi [γ-32P]ATP (6,000 Ci/mmol; Perkin–Elmer), and 10 ng/μl BSA. Reactions were incubated for 40 min at 30°C, stopped by the addition of SDS loading buffer, and resolved on a 6% SDS polyacrylamide gel.

Purification of an FCP1 Kinase from HeLa Nuclear Extract.

The FCP1 kinase was purified according to the scheme shown in Fig. 4A. The FCP1 kinase activity was highly purified (Fig. 4C), and the identity of the four proteins was determined by tandem MS (MS/MS) (33–35). A detailed description of the purification steps and the mass spectrometry can be found in Supporting Text.

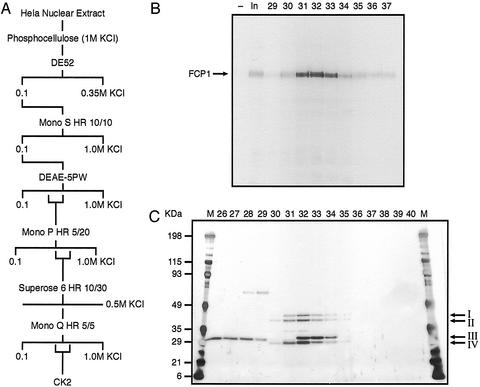

Figure 4.

Purification of an FCP1 kinase from HeLa nuclear extract. (A) Schematic outline of the purification steps used to isolate an FCP1 kinase. (B) FCP1 kinase activity peak of the Mono Q column. In vitro kinase assays were performed with 1.7 μl of the input and 7 μl of the elution fractions of the Mono Q column, which represents the last purification step. Kinase reactions were processed as described in the legend to Fig. 3B. An FCP1 kinase activity peak was observed between the elution fractions 31 and 33. (C) Silver stain of the FCP1 kinase activity peak. Elution fractions around the FCP1 kinase peak of the Mono Q column were separated on a 4–15% SDS polyacrylamide gradient gel and subjected to silver staining. MS/MS was used to identify the four proteins as CK2α (I), CK2α′ (II), HMG1 (III), and CK2β (IV).

Determination of FCP1 in Vivo Phosphorylation Sites.

In separate experiments, ion trap MS/MS was used to determine in vivo phosphorylation sites of FCP1. Two peptides with serine phosphorylation sites were identified: (i) KEAETESQNSELSGVTAGESLDQS575MEEEEEEDTDEDDHLIYLEEILVR and (ii) ENS740PAAFPDR.

For ion trap MS/MS peptide sequencing, FCP1 was isolated by SDS/PAGE, excised, and subjected to reduction, carboxyamidomethylation, and digestion with trypsin. The peptides were analyzed by microcapillary reverse-phase HPLC nanoelectrospray MS/MS on a LCQ DECA XP Plus quadrupole ion trap MS (ThermoFinnigan, San Jose, CA). The ion trap repetitively surveyed m/z 395–1,600, acquiring data-dependent MS/MS spectra for peptide sequence information on the four most abundant precursor ions in the survey scan. A normalized collision energy of 30% and isolation width of 2.5 Da were used, with recurring ions dynamically excluded. Preliminary mapping of peptide sequences was accomplished with the sequest algorithm. The discovery of peptides carrying phosphate and manual interpretation of the MS/MS spectra was facilitated with the in-house programs muquest and fuzzyions, respectively.

Results

Human FCP1 Is a Phosphoprotein.

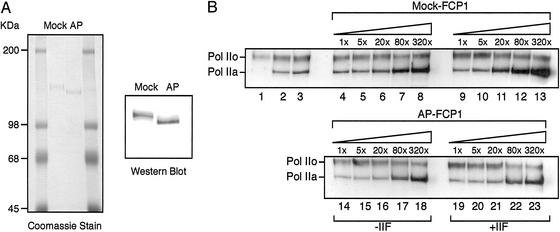

Our initial characterization of human FCP1 suggested that the protein is phosphorylated in vivo. Treatment of FCP1 with AP resulted in the alteration of its mobility on denaturing SDS polyacrylamide gels (Fig. 1A). To further investigate the phosphorylation of FCP1 and whether this modification regulates the activities associated with FCP1, including the CTD phosphatase and elongation stimulatory activities as well as its interaction with TFIIF, we developed a procedure to isolate preparative quantities of dephosphorylated FCP1 as described in Materials and Methods. The two FCP1 isoforms were purified to homogeneity as shown in Fig. 1A. The phosphorylated (mock) and dephosphorylated (AP) forms of FCP1 showed a clear migration difference on 6% SDS polyacrylamide gels, which were stained either with Coomassie blue or probed with an antibody against FCP1 (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

Stimulation of the CTD phosphatase activity by TFIIF depends on the phosphorylation state of FCP1. (A) Dephosphorylation of FCP1 in vitro. Human FCP1 purified from baculovirus-infected SF-9 cells was incubated either with buffer alone (mock) or with buffer containing AP. After phosphatase treatment of FCP1, a DE52 column was used to separate FCP1 from AP. The same procedure was carried out with mock-treated FCP1 (see Materials and Methods). Purified mock- and AP-treated FCP1 were separated on 6% SDS polyacrylamide gels, stained with Coomassie blue (Left), or subjected to Western blot analysis (Right), and probed with a polyclonal antibody against FCP1. (B) CTD phosphatase assays with phosphorylated and dephosphorylated FCP1. CTD phosphatase assays were performed with increasing amounts (0.1–32 fmol) of mock- and AP-treated FCP1 in the absence or presence of TFIIF as indicated. RNAPIIO was used as a substrate. Controls include RNAPIIO that either was not incubated at all (lane 1), or was incubated in the absence (lane 2) or presence (lane 3) of TFIIF. After the phosphatase assay, reactions were separated on a 6% SDS polyacrylamide gel. The phosphorylated and dephosphorylated forms of RNAPII were detected in Western blot analysis with a polyclonal antibody directed against the GAL4-CTD fusion protein by using the enhanced chemiluminescence system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

TFIIF-Mediated Stimulation of the CTD Phosphatase Activity Depends on FCP1 Phosphorylation.

The purified phosphorylated and dephosphorylated forms of FCP1 as shown in Fig. 1A were used in CTD phosphatase assays (Fig. 1B). Both forms of FCP1 were incubated with conventionally purified RNAPIIO as substrate. RNAPIIO was partially dephosphorylated under the assay conditions used. The appearance of RNAPIIA was detected in Western blot analysis by using a polyclonal antibody against the CTD of the largest subunit of RNAPII. The CTD phosphatase assays were performed either in the absence or presence of TFIIF. In the absence of TFIIF, the phosphatase activity associated with both isoforms of FCP1 was dose-dependent, and the levels of activity were quantitatively similar (Fig. 1B). In the presence of TFIIF, however, the CTD phosphatase activity of the phosphorylated form of FCP1 (lanes 9–13) was stimulated 4- to 5-fold, whereas the dephosphorylated form of FCP1 (lanes 19–23) was not responsive to TFIIF (compare lanes 14–18 and 19–23). Quantification (data not shown) revealed only a slight difference in the activity associated with the phosphorylated and dephosphorylated forms of FCP1 in the absence of TFIIF. However, the efficiency of CTD dephosphorylation by FCP1 increases in the presence of TFIIF, and this stimulation requires phosphorylated FCP1.

Transcription Elongation Is Affected by the Phosphorylation State of FCP1.

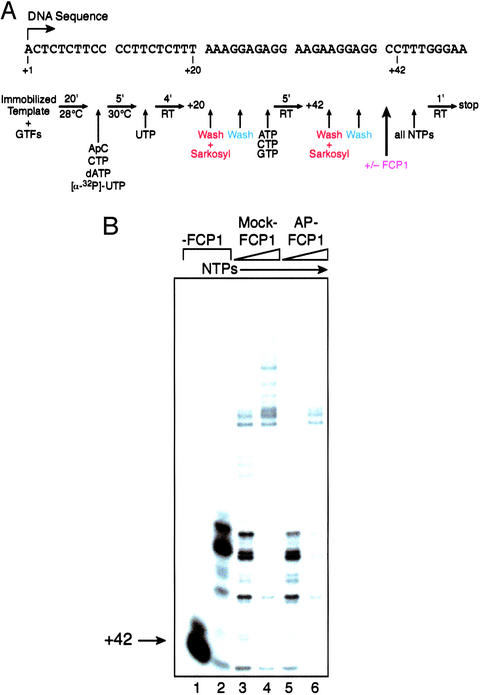

We next analyzed whether the transcription elongation stimulatory activity associated with FCP1 is regulated through phosphorylation (Fig. 2). Transcription elongation assays were performed by using immobilized DNA templates where the elongating polymerase was stalled by nucleotide starvation at position +42. The stalled complexes were washed in a low-salt transcription buffer (100 mM KCl), which does not remove TFIIF from the transcription complex. Transcription elongation was then resumed by the addition of FCP1 and all four ribonucleotides (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

Effect of the phosphorylation state of FCP1 on transcription elongation. (A) Template DNA sequence and schematic of the transcription elongation assay. Stalled +42 complexes were washed as indicated and incubated with or without FCP1 for 20 min at 28°C. After preincubation, the elongation reactions were chased with all four NTPs for 1 min at room temperature and then stopped. Transcription reactions were resolved on 7.5% denaturing polyacrylamide gels in 1× TBE. (B) Transcription elongation by FCP1. Elongation assays were performed with +42 stalled complexes that had been washed with transcription buffer containing 100 mM KCl. These complexes, which contained TFIIF, were preincubated with either 0.2 or 0.4 pmol of mock-treated (lanes 3 and 4) or AP-treated (lanes 5 and 6) FCP1 and then chased in the presence of all four NTPs. Controls include the +42 complex alone (lane 1) and the +42 complex that had been chased with all four NTPs (lane 2) in the absence of FCP1.

Transcription elongation reactions (Fig. 2B) were efficiently stimulated in a dose-dependent manner by the addition of the phosphorylated form of FCP1 (mock-treated; lanes 3 and 4). However, when FCP1 was dephosphorylated, the elongation stimulatory effect was impaired (AP-treated; lanes 5 and 6). These results demonstrate that the phosphorylation state of FCP1 is important for its functional interaction with TFIIF in transcription elongation.

Dephosphorylation of FCP1 Inhibits Its Interaction with TFIIF.

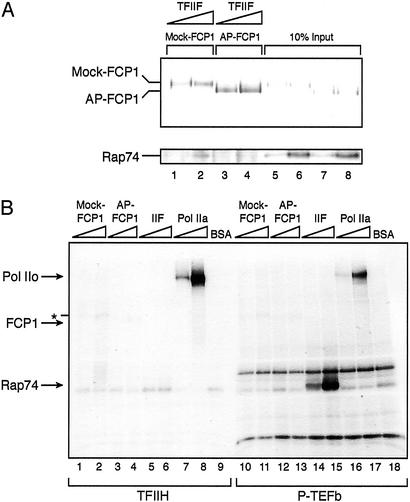

The CTD phosphatase and the transcription elongation activities of FCP1, which are stimulated by TFIIF, are compromised when FCP1 is dephosphorylated (Figs. 1 and 2). To determine whether the phosphorylation state of FCP1 affects its interaction with TFIIF, we performed immunoprecipitation experiments (Fig. 3A). Constant amounts of phosphorylated (lanes 1 and 2) and dephosphorylated (lanes 3 and 4) FCP1 were incubated with increasing amounts of TFIIF and precipitated with a monoclonal antibody against FCP1 bound to protein G agarose. These experiments demonstrated that the inability of dephosphorylated FCP1 to functionally interact with TFIIF is due to its compromised physical association with TFIIF (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

Phosphorylation of FCP1 modulates its interaction with TFIIF. (A) Dephosphorylated FCP1 cannot interact with TFIIF. Immunoprecipitations were carried out with monoclonal antibodies against FCP1. The same amounts of mock-treated (lanes 1 and 2) and AP-treated (lanes 3 and 4) FCP1 were incubated with increasing amounts of TFIIF together with the antibody bound to protein G-agarose. Immunoprecipitates were resolved on a 6% SDS polyacrylamide gel, and Western analyses were performed with polyclonal antibodies against FCP1 and monoclonal antibodies against Rap74, the large subunit of TFIIF. As a control, 10% of the input material of each immunoprecipitation reaction was loaded in lanes 5–8. (B) FCP1 is not phosphorylated by TFIIH or P-TEFb. Increasing amounts (1- and 2-fold) of mock-treated FCP1, AP-treated FCP1, TFIIF, RNAPIIA, or BSA were used in in vitro kinase assays performed with either TFIIH (lanes 1–9) or P-TEFb (lanes 10–18). TFIIH was affinity-purified from an enriched fraction derived from HeLa nuclear extract by using a monoclonal antibody against the ERCC3 subunit of TFIIH. P-TEFb was purified from baculovirus-infected SF-9 cells; impurities resulted in the appearance of two additional labeled bands (lanes 10–18). Kinase reactions were incubated for 40 min at 30°C and separated on a 6% SDS polyacrylamide gel. The gel was blotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane and subjected to autoradiography. The asterisk indicates the position of an unspecific band.

FCP1 Is Not Phosphorylated by TFIIH and P-TEFb.

We further analyzed whether FCP1 was phosphorylated by kinases known to be involved in transcription regulation. The general transcription factor TFIIH contains the kinase CDK7, which phosphorylates the CTD at position Ser-5 during promoter clearance (2, 8). The other known kinase that plays an important role during the elongation step of transcription is P-TEFb, which is composed of CDK9 and cyclin T1. CDK9 preferentially phosphorylates Ser-2 residues within the CTD of the largest subunit of RNAPII and is necessary for the establishment of an elongation-competent complex (2, 8).

Both kinases were tested in in vitro kinase assays by using either phosphorylated FCP1, dephosphorylated FCP1, TFIIF, RNAPIIA or BSA as substrates (Fig. 3B). As expected, TFIIH strongly phosphorylated RNAPIIA in a concentration-dependent manner (lanes 7 and 8) but did not phosphorylate any of the other substrates. On the other hand, P-TEFb efficiently phosphorylated RAP74, the large subunit of TFIIF (lanes 14 and 15) and RNAPIIA (lanes 16 and 17) but not FCP1 or BSA. Taken together, these results establish that TFIIH and P-TEFb are not able to phosphorylate FCP1.

Purification of an FCP1-Specific Kinase from HeLa Nuclear Extract.

Toward identifying the kinase that phosphorylates FCP1, HeLa nuclear extract was subjected to fractionation according to the purification scheme outlined in Fig. 4A by using dephosphorylated FCP1 as a substrate in kinase assays.

The last purification step, a Mono Q column, demonstrates a tight peak of activity eluting at 430 mM KCl (Fig. 4B). Silver staining of the column fractions revealed the presence of four polypeptides coeluting with activity (Fig. 4C). Identification of the four polypeptides by MS revealed the 45-, 41-, 26-, and 25-kDa bands as casein kinase 2 (CK2)α, CK2α′, HMG1, and CK2β, respectively. CK2 is comprised of the subunits CK2α, CK2α′, and CK2β, and the differences in FCP1 kinase activity among the elution fractions reflect a dose-dependent effect related to the amount of CK2 present but do not depend on the presence of HMG1 (compare Fig. 4 B and C).

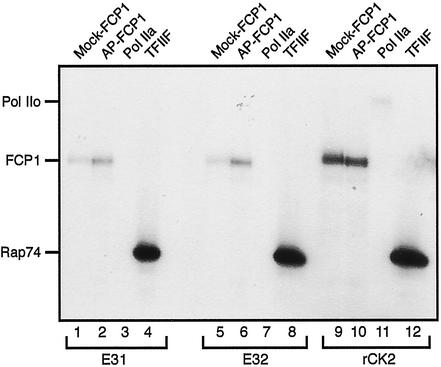

Specificity of the Purified FCP1 Kinase CK2.

CK2 has been identified as the kinase that can phosphorylate FCP1. To assess the specificity of CK2, various substrates including FCP1, RNAPII, and TFIIF were tested in in vitro kinase assays (Fig. 5). The kinase activities of CK2 elution fractions, either lacking (E31; lanes 1–4) or containing (E32; lanes 5–8) HMG1, were tested and compared with recombinant human CK2 (lanes 9–12). CK2 purified from HeLa cells targeted both isoforms of FCP1. However, dephosphorylated FCP1 was more efficiently phosphorylated (compare lanes 1 and 5 with 2 and 6). In addition, CK2 efficiently phosphorylated RAP74, the large subunit of TFIIF (lanes 4 and 8). Importantly, RNAPII was not efficiently used as a substrate by purified CK2 (lanes 3 and 7). These experiments also demonstrate that HMG-1 does not affect the substrate specificity of CK2 (compare lanes 1–4 and 5–8). As a control, recombinant human CK2 used in in vitro kinase assays with the same substrates (lanes 9–12) displayed the same specificity as CK2 purified from HeLa cells. Taken together, CK2 phosphorylates FCP1 and TFIIF, both of which are factors crucial for the recycling of RNAPII and the regulation of transcript elongation.

Figure 5.

Specificity of the purified FCP1 kinase CK2. In vitro kinase assays with purified or recombinant human CK2. Kinase reactions were performed with the Mono Q elution fractions E31 and E32, either lacking or containing HMG1 (Fig. 4C), and recombinant human CK2 (NEB) in the presence of the following substrates: mock-treated FCP1, AP-treated FCP1, RNAPIIA, and TFIIF. Kinase reactions were processed as described in the legend to Fig. 3B.

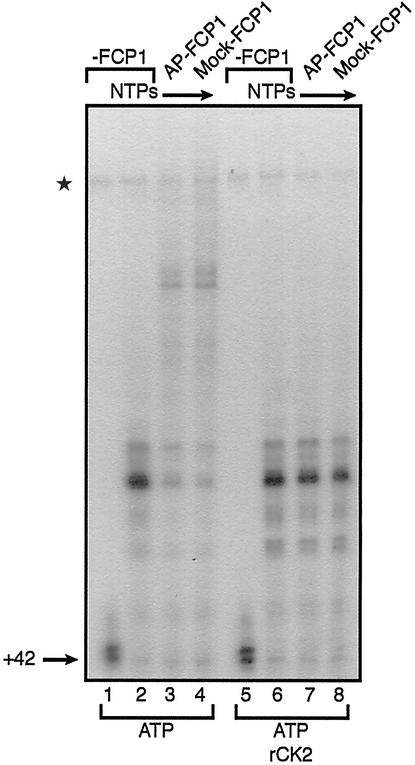

Phosphorylation of FCP1 by CK2 Inhibits the Transcription Elongation Activity of FCP1.

Having shown that dephosphorylation of FCP1 inhibits its ability to stimulate transcription elongation (Fig. 2B), we next asked whether rephosphorylation of FCP1 with CK2 can reestablish its transcription elongation activity (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

CK2 inhibits transcription elongation by FCP1. Transcription elongation assays were performed as described in the legend to Fig. 2A. Elongation reactions contained +42 stalled complexes that had been washed with low-salt transcription buffer (100 mM KCl). These complexes, which contained TFIIF, were preincubated for 10 min at room temperature with 0.2 pmol of mock-treated (lanes 3 and 7) or AP-treated (lanes 4 and 8) FCP1 and 100 μM ATP as well as recombinant human CK2 (NEB, Beverly, MA) as indicated. Elongation reactions were then chased in the presence of all four NTPs. Controls include the +42 complex alone (lanes 1 and 5) and the +42 complex that had been chased with all four NTPs (lanes 2 and 6) in the absence of FCP1. The asterisk indicates the position of an unspecific band.

Transcription elongation assays were performed as described in Fig. 2A. Elongating polymerase was stalled by nucleotide starvation at position +42, and the stalled complexes were washed in low-salt transcription buffer. Transcription elongation complexes containing TFIIF were then incubated with FCP1, recombinant human CK2, and ATP, as indicated (Fig. 6). After a short incubation time that allowed rephosphorylation of FCP1, transcription elongation was resumed by the addition of all four ribonucleotides.

Transcription elongation reactions performed in the presence of ATP but in the absence of CK2 were in accordance with the results shown in Fig. 2B. Phosphorylated FCP1 was more active in transcription elongation when compared with dephosphorylated FCP1 (Fig. 6, lanes 3 and 4). However, in the presence of CK2, the transcription stimulatory activities of both the phosphorylated and dephosphorylated forms of FCP1 are strongly inhibited (Fig. 6, lanes 7 and 8). Interestingly, CK2 did not influence transcription elongation activities in reactions that did not contain FCP1 (Fig. 6, compare lanes 2 and 6). We conclude that the inhibitory effect on transcription elongation by CK2 is FCP1-specific. It seems likely that phosphorylation of both FCP1 and TFIIF by CK2 (Fig. 5) interferes with their functional interaction and therefore inhibits transcription elongation.

Discussion

In the present study, we investigated the influence of the phosphorylation state of FCP1 on its functional properties. We demonstrate that FCP1 is a phosphoprotein in vivo and developed a procedure to isolate phosphorylated and dephosphorylated versions of FCP1 (Fig. 1A). Using these purified isoforms, we found that phosphorylation of FCP1 is important for its optimal CTD phosphatase (Fig. 1B) and transcription elongation (Fig. 2) activities. Both activities associated with FCP1 were stimulated by TFIIF.

In the presence of TFIIF, the phosphorylated form of FCP1 displays ≈3- to 5-fold more CTD phosphatase activity, which is in accordance with previous studies (14). However, the CTD phosphatase activity of dephosphorylated FCP1 was not further enhanced by TFIIF. A similar picture emerged when we performed transcription elongation assays in the presence of TFIIF. We demonstrate that the phosphorylated form of FCP1 effectively stimulated transcription elongation, whereas dephosphorylated FCP1 displayed much less activity. Because a physical interaction between FCP1 and Rap74, the large subunit of TFIIF, is well established (14, 17–19, 24), we tested whether the phosphorylation state of FCP1 influences its interaction with TFIIF. Performing immunoprecipitation experiments (Fig. 3A), we established that phosphorylation of FCP1 is required for its physical interaction with TFIIF.

Computer-assisted analysis (phosphobase Ver. 2.0) revealed a large number of potential phosphorylation sites throughout FCP1. To identify the sites that are phosphorylated in vivo, human FCP1 purified from baculovirus-infected SF9 cells was subjected to ion trap MS/MS. Two in vivo phosphorylation sites within the C terminus of FCP1 at Ser-575 and Ser-740 were identified (see Materials and Methods). Interestingly, both residues lie within the Rap74 interaction domain of FCP1 (17–19). These data further support the observation that the phosphorylation state of FCP1 modulates its physical interaction with TFIIF and affects its properties depending on TFIIF such as CTD phosphatase as well as transcription elongation activities. It is tempting to speculate that the interaction surfaces are created or exposed upon a conformational change after phosphorylation of FCP1.

Because the transcription initiation and elongation factors TFIIH (9) and P-TEF-b (11), containing kinases regulating the phosphorylation state of RNAPII, were not able to phosphorylate FCP1 (Fig. 3B), we set out to purify an FCP1 kinase from HeLa nuclear extract and identified CK2 (Fig. 4). In addition to FCP1, CK2 also phosphorylated RAP74, the large subunit of TFIIF (Fig. 5). This is consistent with previous reports demonstrating that TFIIF is highly phosphorylated in vivo (36). It has been suggested that phosphorylation of TFIIF leads to a conformational change that increases its ability to stimulate transcription initiation as well as elongation (36–38). It is thus tempting to speculate that FCP1 and TFIIF, two regulatory proteins involved in CTD dephosphorylation and transcription elongation, could be phosphorylated and regulated by CK2.

The ability of CK2 to reactivate dephosphorylated FCP1 was tested in CTD phosphatase assays (data not shown). However, reactivation of dephosphorylated FCP1 was not observed, in contrast to recently published data showing that bacterially expressed FCP1 from Xenopus laevis can be activated upon phosphorylation with CK2 (39). It is possible that the effect seen with Xenopus FCP1 is species-specific. Alternatively, the choice of the expression system might have caused the functional difference observed. Additional modifications, present in FCP1 isolated from baculovirus-infected insect cells, such as phosphorylation at other sites, acetylation, and methylation, might affect FCP1 activity and the site of phosphorylation by CK2. In addition, CK2 was not capable of reactivating the transcription elongation activity of dephosphorylated FCP1 (Fig. 6). Surprisingly, CK2 inhibited transcription elongation regardless of the phosphorylation state of FCP1. The negative effect seen with CK2 is FCP1-specific, because in the absence of FCP1 transcription elongation proceeded normally. We speculate that phosphorylation of FCP1 or other components of the elongation complex by CK2 might induce conformational changes that abrogate their functional interaction.

Taken together, our data present evidence that CK2 is not sufficient to reconstitute the CTD phosphatase and transcription elongation activities of dephosphorylated FCP1. We suggest that a combination of phosphorylation sites involving different kinases might be required to reconstitute fully active FCP1. This hypothesis is supported by data obtained during the purification of the FCP1 kinase CK2 (Fig. 4). We have observed two additional FCP1 kinase activities, which do not contain CK2 as determined by Western analyses (data not shown). Future studies will be required to identify the kinases involved and to determine their impact on the regulation of FCP1 function.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Tadashi Wada and Jun Hasegawa for recombinant P-TEFb; Dr. Hua Lu for CK2; Dr. Donal Luse for plasmid pML20-47; Lynne Lacomis for help with MS; and members of the Reinberg laboratory, especially Drs. Christian Schwerk and Mandal Subhrangsu, for helpful discussions. This work was supported by National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA08748 (to P.T.), National Institutes of Health Grant GM 37120 (to D.R.), the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (D.R.), and a fellowship of the Ciba–Geigy Jubiläumsstiftung (Novartis Foundation; to E.M.F.).

Abbreviations

- CTD

C-terminal domain

- RNAPII

RNA polymerase II

- RNAPIIO

hypophosphorylated RNAPII

- CK2

casein kinase 2

- AP

alkaline phosphatase

- MS/MS

tandem MS

References

- 1.Woychik N A, Hampsey M. Cell. 2002;108:453–463. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00646-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Conaway J W, Shilatifard A, Dvir A, Conaway R C. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25:375–380. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01615-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hampsey M, Reinberg D. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1999;9:132–139. doi: 10.1016/S0959-437X(99)80020-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Orphanides G, Lagrange T, Reinberg D. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2657–2683. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.21.2657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dahmus M E. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:19009–19012. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.32.19009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chesnut J D, Stephens J H, Dahmus M E. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:10500–10506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu H, Flores O, Weinmann R, Reinberg D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:10004–10008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.22.10004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Komarnitsky P, Cho E J, Buratowski S. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2452–2460. doi: 10.1101/gad.824700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akoulitchev S, Makela T P, Weinberg R A, Reinberg D. Nature. 1995;377:557–560. doi: 10.1038/377557a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cho E J, Kobor M S, Kim M, Greenblatt J, Buratowski S. Genes Dev. 2001;15:3319–3329. doi: 10.1101/gad.935901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peng J, Zhu Y, Milton J T, Price D H. Genes Dev. 1998;12:755–762. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.5.755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akoulitchev S, Chuikov S, Reinberg D. Nature. 2000;407:102–106. doi: 10.1038/35024111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chambers R S, Dahmus M E. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:26243–26248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chambers R S, Wang B Q, Burton Z F, Dahmus M E. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:14962–14969. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.25.14962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cho H, Kim T K, Mancebo H, Lane W S, Flores O, Reinberg D. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1540–1552. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.12.1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chambers R S, Kane C M. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:24498–24504. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.40.24498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Archambault J, Chambers R S, Kobor M S, Ho Y, Cartier M, Bolotin D, Andrews B, Kane C M, Greenblatt J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:14300–14305. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Archambault J, Pan G, Dahmus G K, Cartier M, Marshall N, Zhang S, Dahmus M E, Greenblatt J. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:27593–275601. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.42.27593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kobor M S, Simon L D, Omichinski J, Zhong G, Archambault J, Greenblatt J. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:7438–7449. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.20.7438-7449.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palancade B, Dubois M F, Dahmus M E, Bensaude O. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:6359–6368. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.19.6359-6368.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lehman A L, Dahmus M E. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:14923–14932. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.20.14923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marshall N F, Dahmus M E. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:32430–32437. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005898200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kobor M S, Archambault J, Lester W, Holstege F C, Gileadi O, Jansma D B, Jennings E G, Kouyoumdjian F, Davidson A R, Young R A, Greenblatt J. Mol Cell. 1999;4:55–62. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80187-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Licciardo P, Ruggiero L, Lania L, Majello B. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:3539–3545. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.17.3539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mandal S S, Cho H, Kim S, Cabane K, Reinberg D. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:7543–7552. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.21.7543-7552.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yao S, Neiman A, Prelich G. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:7080–7087. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.19.7080-7087.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murray S, Udupa R, Yao S, Hartzog G, Prelich G. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:4089–4096. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.13.4089-4096.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee J M, Greenleaf A L. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:10990–10993. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.17.10990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones K A. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2593–2599. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.20.2593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kimura M, Suzuki H, Ishihama A. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:1577–1588. doi: 10.1128/mcb.22.5.1577-1588.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maldonado E, Drapkin R, Reinberg D. Methods Enzymol. 1996;274:72–100. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)74009-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Samkurashvili I, Luse D S. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:5343–5354. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.9.5343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Erdjument-Bromage H, Lui M, Lacomis L, Grewal A, Annan R S, McNulty D E, Carr S A, Tempst P. J Chromatogr. 1998;826:167–181. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(98)00705-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Geromanos S, Freckleton G, Tempst P. Anal Chem. 2000;72:777–790. doi: 10.1021/ac991071n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Winkler G S, Lacomis L, Philip J, Erdjument-Bromage H, Svejstrup J Q, Tempst P. Methods. 2002;26:260–269. doi: 10.1016/S1046-2023(02)00030-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kitajima S, Chibazakura T, Yonaha M, Yasukochi Y. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:29970–29977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou M, Kashanchi F, Jiang H, Ge H, Brady J N. Virology. 2000;268:452–460. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.0177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dikstein R, Ruppert S, Tjian R. Cell. 1996;84:781–790. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81055-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Palancade B, Dubois M F, Bensaude O. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:36061–36067. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205192200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.