Abstract

BACKGROUND

Group B streptococcal (GBS) infection remains a leading cause of neonatal sepsis. Currently, the management guidelines of neonates born to women with unknown GBS status at delivery are unclear. In this cohort, who undergo at least a 48-hour observation, a rapid method of detection of GBS colonization would allow targeted evaluation and treatment, as well as prevent delayed discharge.

OBJECTIVE

The goal of this research was to evaluate the validity of rapid fluorescent real-time polymerase chain reaction in comparison with standard culture to detect GBS colonization in infants born to women whose GBS status is unknown at delivery.

DESIGN/METHODS

Neonates at > 32 weeks’ gestation born to women whose GBS status was unknown at delivery were included. Samples were obtained from the ear, nose, rectum, and gastric aspirate for immediate culture and real-time polymerase chain reaction after DNA extraction using the LightCycler. Melting point curves were generated, and confirmatory agar gel electrophoresis was performed.

RESULTS

The study population (n = 94) had a mean ± SD gestational age of 38 ± 2 weeks and birth weight of 3002 ± 548 g. The rates of GBS colonization by culture were 17% and 51% by real-time polymerase chain reaction. The 4 surface sites had comparable rates of GBS. The overall sensitivities, specificities, and positive and negative predictive values of real-time polymerase chain reaction were: 90%, 80.3%, 28%, and 98.9%.

CONCLUSIONS

Real-time polymerase chain reaction resulted in a threefold higher rate of detection of GBS colonization and had an excellent negative predictive value in a cohort of neonates with unknown maternal GBS status at delivery. Thus, real-time polymerase chain reaction would be a useful clinical tool in the management of those infants potentially at risk for invasive GBS infection and would allow earlier discharge for those found to be not at risk.

Keywords: group B streptococcus, rapid diagnostic tests, polymerase chain reaction, newborn

Abbreviations: GBS—group B streptococcus, PCR—polymerase chain reaction, CI— confidence interval

Group b streptococcus (GBS) remains a leading cause of sepsis and pneumonia in the newborn despite the implementation of universal prenatal screening and intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis in pregnant women.1 The incidence of invasive neonatal GBS infection is currently reported to be 0.5 to 3.0 per 1000 live births, with a 4% to 10% mortality associated with early onset infections within the first week of life.1,2 Preterm infants have higher mortality rates as high as 20% to 30%.3 Infection because of GBS is acquired through fetal aspiration of infected amniotic fluid or during passage through the vaginal canal.4

The 2002 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines suggest that the diagnosis of GBS colonization in pregnant women is best made via culture of a combined rectal and vaginal swab using a selective enrichment (Todd-Hewitt) broth at 35 to 37 weeks’ gestation.5 However, the sensitivity of cultures in detecting GBS colonization varies from 54% to 87%, and results take up to 36 to 48 hours.6,7 Women colonized with GBS based on prenatal screening are candidates for intrapar-tum antibiotic prophylaxis. However, women who present in labor with an unknown GBS status present a challenge. These women are considered candidates for intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent early onset neonatal GBS disease based on a risk-factor analysis. The risk-factor strategy is less sensitive and results in exposure to intrapartum antibiotics of women and fetuses who may not be colonized with GBS.5 In recent years, therefore, rapid methods of detection of GBS colonization in pregnant women have become the focus of investigation. The most promising of these techniques is the fluorescent real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR), which is reported to be highly sensitive and spe-cific among women in labor and to yield results in 30 to 45 minutes.8

GBS colonization rates vary from 10% to 30% in pregnant women and 40% to 70% in neonates born to colonized mothers.9–12 Neonatal colonization occurs primarily after onset of labor or rupture of membranes. Risk factors include a heavily colonized mother, vaginal delivery, prolonged rupture of membranes before delivery, and lack of intrapartum antibiotics.13 A significant proportion of colonized infants (1–3%) acquire invasive early onset disease.

The revised 2002 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines for the management of neonates born to women with an unknown GBS colonization status at delivery are vague.5 The majority of these infants are observed in hospital for ≥ 48 hours. They may undergo a diagnostic evaluation for sepsis in the presence of other maternal risk factors or when the gestational age is < 35 weeks. Infants with signs and symptoms of sepsis would undergo a full diagnostic evaluation and empiric therapy. A rapid method of detection of GBS colonization, if reasonably sensitive and specific, would aid in the risk stratification of this challenging group of neonates. It would more accurately identify colonized infants at risk of invasive disease for additional evaluation and monitoring. Thus, rapid testing for GBS in this population would prevent delayed discharge and unnecessary evaluation of those not at risk for invasive disease. There is currently limited data on the validity of rapid methods of detection of GBS colonization in neonates.14,15 The objective of this prospective study was to evaluate the real-time fluorescent PCR method, in comparison with standard culture, for the detection of GBS colonization in neonates born to women whose GBS status is unknown at delivery.

METHODS

The study was conducted at Hutzel Women’s Hospital (Detroit, MI) from July 2002 to March 2004. The Human Investigation Committee of Wayne State University approved the study, and written informed consent was obtained from the parents.

Subject Selection

Neonates at > 32 weeks’ gestation whose maternal GBS status was unknown at delivery were enrolled. The reasons that were determined for an unknown GBS colonization status in the pregnant woman at delivery included lack of prenatal care, unavailability of prenatal laboratory results, and preterm labor before 35 weeks. Critically ill infants and those in whom a decision not to provide full support had been made were excluded.

Clinical Data

Maternal data recorded included age, race, previous history of infants with invasive GBS disease, details of intrapartum antibiotics received, presence of GBS bacte-riuria, chorioamnionitis, and duration of rupture of membranes. Maternal chorioamnionitis was defined clinically based on the obstetrician’s documentation. Spe-cific clinical signs, such as fever ≥100.4°F, foul smelling liquor, fetal tachycardia, and placental pathology, when available, were noted to confirm the diagnosis. Infant data, such as gestational age, gender, birth weight, the results of a diagnostic evaluation, if performed, and details of antibiotic therapy were abstracted. The duration of hospitalization, course in hospital, and mortality data were also reviewed.

Procedures

All of the enrolled neonates underwent collection of simultaneous specimens from surface sites for culture and real-time PCR before their first bath and within 4 hours of delivery. All of the specimens were collected by the investigators using a double swab collection and transport system (CultureSwab, Becton Dickinson Microbiology Systems, Cockeysville, MD) from the nares, external auditory canals, rectum, and gastric aspirate, with a turning motion for 30 seconds. Gastric aspirate was collected using an 8F suction catheter, which was passed orally into the stomach. The aspirate was collected in a DeLee tube, and a swab was obtained for culture. One swab from each site (a total of 4) was immediately crushed in Stuart’s medium and sent to the microbiology laboratory for isolation by culture, and the other samples (3 swabs and the gastric aspirate) were stored at − 70°C until the real-time PCR assay was performed.

Culture

Swabs were inoculated onto standard selective Todd Hewitt broth medium enriched with gentamicin and nalidixic acid for 18 hours, then subcultured on blood agar plates and incubated in ambient air for 48 hours. GBS identity was confirmed by β hemolysis on blood agar and serologic grouping. The results were reported as “no growth,” “rare,” “moderate,” and “too numerous to count” colonies.

Real-Time PCR Using LightCycler Technology

The LightCycler (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) technology combines the PCR reaction with real-time detection of fluorescently tagged amplified products after each cycle.

DNA Extraction

Genomic DNA from 5 commercially available GBS strains (ATCC 13813, 12400, 12403, 12973, and 27591) served as positive controls. DNA from patient specimens and positive controls were extracted using the QIAamp kit (Qiagen Inc, Chatsworth, CA).

Primers complementary to the cyclic adenosine monophosphate factor gene region of Streptococcus aga-lactiae were synthesized (Introgen Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) to amplify genomic DNA.16 Real-time PCR amplification with the forward (5′-TTTCACCAGCT-GTATTAGAAGTA-3′) and reverse (5′-GTTCCCTGAA-CATTATCTTTGAT-3′) primers yielded a product of 153 base pairs (Fig 1). This product was detected using a fluorescent dye, SYBR Green 1, which dramatically increased the emitted light on excitation after annealing of the primers. During elongation, there was a progressive increase in florescence, which was monitored in real time at the end of each PCR cycle. PCR reactions were performed according to the LightCycler kit instructions using master mixes supplied by Roche Diagnostics with 0.5 μM of each (synthesized) primer.16,17

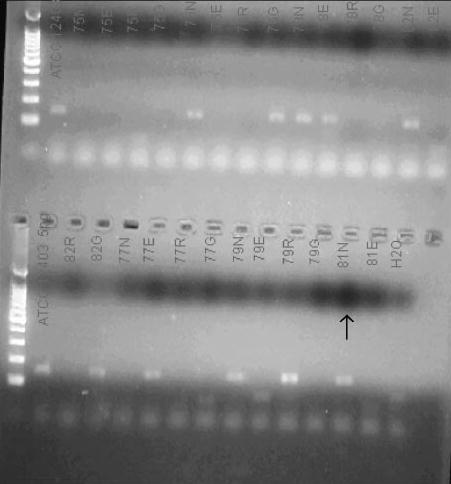

FIGURE 1.

A photograph of the confirmatory 2% agar gel electrophoresis showing the target 153 bp product.

To augment the specificity of the amplified product, 2 adjacent probes (STB-F/STB-C), 1 labeled with fluo-rescein and the other with Cy5 (TIB Molbiol LLC, Adel-phia, NJ), hybridizing to GBS-specific amplicons, were used to generate increased fluorescence at a specific wavelength (fluorescence resonance energy transfer principle). The number of PCR cycles for the probe hybridization assay was 60 cycles. The LightCycler software (version 3.5) was used to detect the signal.

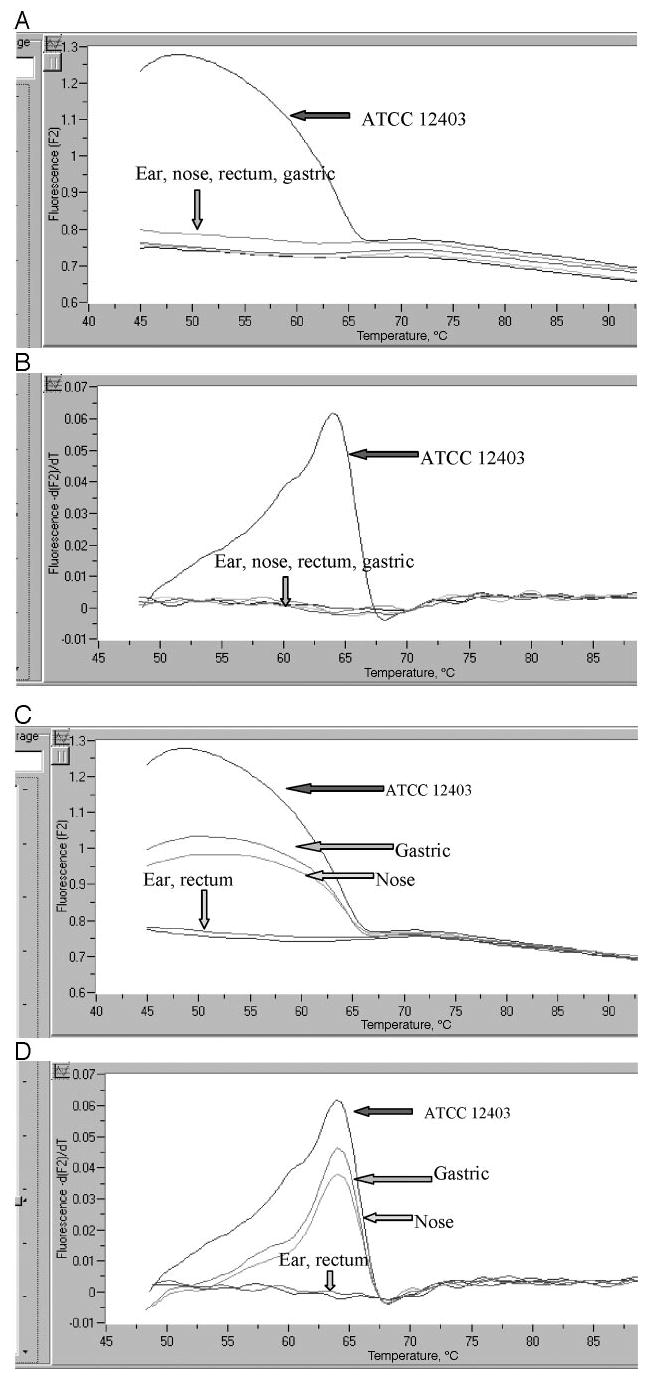

A melting curve was generated for each specimen to confirm the amplified product. The melting curve evaluation was performed with a rapid heating step to denature all DNA (94°C at 0 seconds holding time), cooling below the annealing temperature and then slow heating at 0.2°C /seconds to monitor the melting temperature of the double-stranded DNA. The curve generated is a plot of the first negative derivative of florescence against temperature (Fig 2). The melting point generated for GBS was 65.3 ± 2.5°C. Representative melting curves with the presence of GBS with a temperature identical to the control are shown (Fig 2). Because the positive controls all generated identical melting curves, ATCC 12403 served as a positive control for all of the specimen runs (Fig 2). Each cycle was run with 5 different concentrations (0.05, 0.5, 5, 50, and 500 pg/μL) of the positive control (ATCC 12403) and a negative control (water) for comparison. Only samples that showed a positive deflec-tion at or a lower cycle number than the 0.5 pg/μL positive control were interpreted as positive for GBS. Gel electrophoresis (2% agarose) was used to confirm the real-time PCR products (Fig 1).

FIGURE 2.

Melting curves (A and C plot the fluorescence and temperature; B and D show the first negative derivative of fluorescence and temperature) where all samples were negative for GBS (A and B), samples from the nose and gastric aspirate were positive, and those from ear and rectum were negative (C and D).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software (version 12, SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). Sample size was predetermined to limit the size of the 2-tailed 95% con-fidence intervals (CIs) for the negative predictive value of real-time PCR to 0.1, within 0.05 of the true value, which was taken as 95%.18 Based on these assumptions, the estimated sample size was 72 patients with negative results. The negative predictive value was chosen for sample size calculations because of its clinical use in evaluating a screening test for the purpose of preventing unnecessary evaluation and therapy.

Data were reported as mean ± SD, number, and percentage as appropriate. Patient and maternal characteristics, as well as clinical outcomes, were compared in the groups who had and did not have GBS colonization, by culture and real-time PCR, using t test, χ2 test, and Fisher’s exact test to determine significance. The rates of GBS colonization at each site were calculated by culture and real-time PCR. The sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values for real-time PCR were derived by comparison with simultaneous culture by cross-tabulations. The 95% CIs for these parameters were computed by a general method based on “constant χ2 boundaries” using a 2-way contingency table.19

RESULTS

After screening for eligibility in this study, consent was obtained on 94 infants with an unknown maternal GBS status at delivery. Culture was performed on 376 samples and real-time PCR on 371. Five samples could not be processed for PCR because they were contaminated or broken during DNA extraction.

Patient Characteristics

The mean (± SD) birth weight of the study cohort was 3002 ± 548.5 g, and gestation was 38 ± 2 weeks. Males comprised 53.2% (n = 50) of the cohort. A diagnostic evaluation (complete blood cell count and blood culture) was performed in 45 (47.9%) infants. There was no case of early onset invasive GBS disease in our cohort. Blood culture was positive in a single infant for Klebsiella pneumoniae. The total white blood count was > 20 000 in 6 infants and > 4000 in 1.

A total of 27 (28.7%) infants were admitted to the nursery, and 25 (26.6%) received empiric antibiotic treatment. Of these, 23 received ampicillin and cefo-taxime, the standard empiric treatment for possible sepsis at our institution, and 2 received penicillin alone. Empiric antibiotics were initiated for clinical signs of sepsis or for suggestive findings on the complete blood cell count. The median duration of stay in hospital was 3 days (mean: 4.3; mode: 2 days) with a range of 1 to 38 days.

The mean ± SD maternal age was 25.7 ± 6.7 years with a range of 15 to 42 years; 81.9% were black. Chorioamnionitis was present in 24 women (25.5%); 11 (11.7%) by clinical criteria alone, whereas 13 (13.8%) were confirmed by placental pathology. Eleven women (11.7%) had prolonged rupture of membranes for > 18 hours before delivery. GBS bacteriuria was noted in 4 women (4.2%), and 3 (3.1%) had a history of a previous infant with GBS disease. Antibiotics had been administered before delivery to 22 women (23.4%) for risk factors. Ampicillin alone was administered to 8 women, 7 women received ampicillin along with another antibacterial, 5 received clindamycin or vancomycin, and 2 received cefazolin.

Rates of GBS Colonization by Culture and Real-Time PCR

Overall, there were 16 patients (17%) who were colonized at 1 or more sites by culture; real-time PCR detected colonization at any site in 48 infants (51%). GBS was detected by culture and real-time PCR in 9 (9.5%) and 23 (24.7%) samples, respectively, from the ear, in 7 (7.4%) and 24 (25.8%) samples from the nose, in 5 (5.3%) and 22 (23.6%) samples from the rectum, and in 9 (9.5%) and 25 (27.1%) samples from the gastric aspirate. GBS was isolated from 30 of the 376 specimens by culture and detected in 94 of 371 specimens by real-time PCR. Table 1 depicts the percentage of specimens with concordant and discordant results by the 2 techniques at each site and overall.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of the Results Obtained by Culture and Real-Time PCR at Each Surface Site (Ear, Nose, Rectum, and Gastric Aspirate) and Overall

| Culture, PCR | Ear, N (%) | Nose, N (%) | Rectum, N (%) | G Aspirate, N (%) | Total, N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neg, neg | 70 (75.2) | 69 (74.2) | 69 (74.2) | 66 (71.7) | 274 (73.8) |

| Pos, pos | 9 (9.7) | 7 (7.5) | 3 (3.2) | 8 (8.7) | 27 (7.3) |

| Pos, neg | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (2.1) | 1 (1.1) | 3 (0.8) |

| Neg, pos | 14 (15.1) | 17 (18.3) | 19 (20.5) | 17 (18.5) | 67 (18.1) |

| Total | 93 | 93 | 93 | 92 | 371 |

Neg indicates negative; Pos, positive.

Among the 22 infants whose mothers were treated with antibiotics before delivery, GBS surface colonization was observed in 4 (18.2%) by culture and 11 (50%) by real-time PCR. Of the infants without exposure to maternal antibiotics, 16.7% (12 of 72) and 52.1% (37 of 71) were colonized with GBS by culture and real-time PCR, respectively. These differences were not statistically significant (P = .87), although the study was not powered to evaluate these differences.

Sensitivity, Specificity, and Positive and Negative Predictive Values of Real-Time PCR

Table 2 shows the sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values of real-time PCR in comparison with cultures at each site and overall along with the 95% CIs for each value. Overall, the sensitivity of the real-time PCR was 90% (95% CI: 79.2–100%), spec-ificity was 80.3% (95% CI: 76–84%), and positive and negative predictive values were 28 (95% CI: 19.5–38) and 98.9 (95% CI: 97.6–100%), respectively. The sensitivities were highest for the ears and nose (100%; 95% CI: 72–100% and 100%; 95% CI: 67–100%, respectively) whereas the negative predictive values were consistently high in all of the sites.

TABLE 2.

Sensitivities, Specificities, and Positive (PPV) and Negative Predictive Values (NPV) and 95% CIs for Real-Time PCR Compared With Culture in the Detection of GBS Colonization in Neonates

| Variable | Ear, Value (95% CI) | Nose, Value (95% CI) | Rectal, Value (95% CI) | Gastric Aspirate, Value (95% CI) | Any Site, Value (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 100 (72.7–100) | 100 (66.8–100) | 60 (23.7–88) | 88.9 (58.8–98) | 90 (79.2–100) |

| Specificity | 83.3 (80.4–83.3) | 80.2 (77.5–80.2) | 78.4 (76.3–80) | 79.5 (76.3–80) | 80.3 (76.1–84.5) |

| PPV | 39.1 (28.4–39.1) | 29.2 (19.5–29.2) | 13.6 (5.4–20) | 32 (21.2–35.3) | 28 (19.5–38) |

| NPV | 100 (96.5–100) | 100 (96.6–100) | 97.2 (94.6–99) | 98.5 (94.5–97) | 98.9 (97.6–100) |

Degree of Colonization

Based on previous epidemiological studies, heavy colonization was defined a priori as colonization at ≥3 sites. Of the 48 infants in whom GBS colonization was detected by real-time PCR, 13 were colonized at ≥3 sites. Two of them were also classified as heavily colonized by culture, 8 as lightly colonized, and 3 were negative. Conversely, of the 16 infants with colonization by culture, 3 were heavily colonized; 2 of them were also heavily colonized by real-time PCR, whereas 1 was lightly colonized (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Degree of Colonization of Patients by Culture and Real-Time PCR

|

Culture |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| PCR | Heavy (n = 3) | Light (n = 13) | Negative (n = 32) |

| Heavy (n = 13) | 2 | 8 | 3 |

| Light (n = 35) | 1 | 5 | 29 |

| Total (n = 48) | 3 | 13 | 32 |

Correlation of Clinical Characteristics and Outcomes With GBS Colonization

There were no significant differences in the groups of infants with and without GBS colonization, whether by culture or real-time PCR in maternal risk factors, such as chorioamnionitis, prolonged rupture of membranes, or intrapartum antibiotics. Infant characteristics including gestation, gender, length of hospitalization, and the proportion of infants who underwent diagnostic evaluation or received antibiotic treatment were comparable in the 2 groups (Table 4). There were significantly more mothers with a history of a previously affected GBS infant (P = .014) and GBS bacteriuria (P = .015) among the neonates who were GBS colonized by culture than those who were negative.

TABLE 4.

Infant and Maternal Characteristics in the Groups With and Without GBS Colonization by Culture and Real-Time PCR

| Clinical Characteristics | Real-Time PCR Positive (n = 48) | Real-Time PCR Negative (n = 45) | Culture Positive (n = 16) | Culture Negative (n = 78) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age, yr, mean ± SD | 25.4 ± 6.5 | 26.2 ± 6.9 | 25.7 ± 6.6 | 25.7 ± 6.7 |

| Black race, % | 38 (79.1) | 38 (84.4) | 14 (87.5) | 63 (80.7) |

| Chorioamnionitis, % | 8 (16.6) | 16 (35.5) | 1 (6.25) | 23 (29.4) |

| Maternal antibiotics, % | 11 (22.9) | 11 (24.4) | 4 (25) | 18 (23) |

| PROM > 18 h, % | 6 (12.5) | 5 (11.1) | 1 (6.25) | 10 (12.8) |

| Previous GBS infant, % | 3 (6.25) | 0 | 3 (18.75) | 0 (0%)a |

| GBS bacteriuria, % | 3 (6.25) | 1 (2.2) | 3 (18.7) | 1 (1.2)a |

| Gestation, wk, mean ± SD | 38.2 ± 2 | 37.9 ± 2 | 38.6 ± 1.5 | 37.9 ± 2.1 |

| Male gender, % | 24 (50) | 25 (55.5) | 9 (56.2) | 41 (52.5) |

| Nursery admission, % | 13 (27) | 14 (31.1) | 4 (25) | 23 (29.4) |

| Septic evaluation, % | 23 (47.9) | 22 (48.8) | 4 (25) | 41 (52.5) |

| Antibiotic use, % | 5 (10.4) | 3 (6.6) | 2 (12.5) | 6 (7.6) |

| Duration of stay, d, mean ± SD | 4.15 ± 3.6 | 4.5 ± 5.6 | 4 ± 3.5 | 4.41 ± 4.8 |

P < .05.

DISCUSSION

Infants born to women whose GBS colonization status is unknown at the time of delivery are currently observed in the hospital for ≥48 hours and evaluated and perhaps treated for sepsis in the presence of clinical signs or maternal risk factors. Rapid identification of GBS colonization in this subgroup of neonates is critical for a more targeted and cost-effective approach to neonatal management. For this purpose, we evaluated the technique of real-time PCR, which has been found previously to be highly sensitive and specific for the diagnosis of GBS colonization in pregnant women and in certain other infections in children.20–22 Our study demonstrates that the real-time PCR has excellent sensitivity (90%; 95% CI: 79–100%), specificity (80%; 95% CI: 76–84%), and negative predictive values (98.9%; 95% CI: 97.6–100%) when compared with culture.

The prevalence of GBS colonization by culture in our study (17%) is concordant with the reported rates of maternal GBS carriage and vertical transmission. The low incidence of documented early onset GBS disease and early onset sepsis, in general, were as expected. The proportion of mothers who received antibiotics before delivery (23.4%) was concordant with data in other unscreened populations (25–33%).23,24 Neonates born to women with a previous GBS-infected infant or GBS bacteriuria are well established to be at high risk for infection and, expectedly, were found to be more likely to be colonized.4,5 Real-time PCR had a higher detection rate, when compared with surface cultures (51% vs 17%), with the ears and nose being the best sites for detection. The reason we believe the increased detection by real-time PCR represents true GBS colonization rather than nonspecific results or false positives is that the assay was performed under stringent conditions for specificity, both inherent and imposed. Each sample was run with positive controls of different concentrations, and only samples that showed a deflection of the curve at a lower cycle number than the control with the concentration of 0.5 pg/mL were treated as positive. The melting curve analysis and the agar gel electrophoresis were additional conditions for enhanced specificity.

The increased sensitivity of detection by real-time PCR has also been reported in other studies. In group A streptococcal throat infections, real-time PCR detected more patients than standard cultures, when discordant results were reconciled by a review of the patients’ histories.25 A consistent increase in sensitivity compared with standard culture has also been reported using the real-time PCR (LightCycler technology) in assays for Bordetella pertussis, herpes simplex virus, varicella zoster virus, and cytomegalovirus.22,26–28 In meningococcal disease, for example, real-time PCR was positive in blood or spinal fluid in 23 patients compared with 15 by culture when a combination of clinical and laboratory criteria were used as “gold standard” diagnostic criteria.29 Similarly, the real-time PCR technique significantly increased the detection rate of respiratory viruses compared with traditional methods in a cohort of pediatric patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.21 In several of these studies, real-time PCR was positive before culture and remained so after treatment with antibiotics when cultures turned negative. The most plausible explanation for the difference in detection rates by culture and real-time PCR in our study is that intrapar-tum antibiotics given to women may have decreased the degree of neonatal colonization to below the sensitivity of cultures. The impact of intrapartum antibiotic prophy-laxis on the prevalence of neonatal colonization from 40% to 50% to as low as 3% to 9% has been established previously.13,30 However, our study was not powered to detect a statistical difference in the rates of colonization by culture or real-time PCR among infants whose mothers were exposed to antibiotics and those who were not.

Another explanation for the increased detection of colonization by real-time PCR may be the low and variable sensitivity of culture. A recent review identified 25 cases of early onset GBS disease in the era of universal maternal screening with standardized laboratory techniques of culture, of whom 16 mothers had negative antenatal cultures.31 Other studies have reported sensitivities of antenatal GBS cultures as low as 54%.7 Failure to culture GBS in the mother, even with ideal sampling and culture techniques, therefore, is well documented and has been attributed, among other things, to the use of oral antibiotics and feminine hygiene products.32 Currently, diagnostic surface cultures in neonates are not used routinely for the identification of GBS disease, because only a very small proportion of infants with surface colonization develop invasive GBS disease. However, detection of surface colonization using a sensitive screening method would identify infants who are potentially at risk for invasive GBS disease. Although rare, the high morbidity and mortality associated with invasive GBS disease suggests that the enhanced detection of GBS colonization by real-time PCR compared with cultures may be clinically meaningful and may guide clinical management and resource allocation.

In our study, in 3 samples positive for GBS colonization by culture, real-time PCR failed to detect GBS; 2 were from the rectum, and 1 was a gastric aspirate sample. We speculate that there may have been contamination from meconium or amniotic fluid in these samples. There are limited data that interfering substances, such as blood, meconium, and amniotic fluid may affect the results of real-time PCR assay.33 In our study, although the rates of GBS colonization were comparable in the 4 sites, the ears and nose may be superior sampling sites to eliminate the possibility of cross-contamination from other organisms. Previous reports on real-time PCR assays for other organisms, such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, have suggested that variations in the targeted gene sequence in some isolates may have prevented their amplification with the selected primers.34,35

In a previous study involving pregnant women, the real-time PCR detected GBS colonization in 32 combined anal and vaginal specimens compared with 33 specimens by culture, with reported sensitivities of 97% (95% CI: 82.5–99.8%) and specificity of 100% (95% CI: 94.2–100%).8 The reason for the close concordance between the techniques in that study, in contrast to ours, could be because of differences in patient characteristics. Neonates are typically colonized only briefly after rupture of membranes. Thus, their bacterial load is likely to be lower and isolation by culture more difficult. In addition, intrapartum antibiotics may alter detection by culture, as discussed previously. In the cited study by Bergeron et al,36 only 4 women received antibiotics before sampling, whereas 22 of 94 infants in our cohort had been exposed to at least 1 dose of maternal antibiotic. Results more similar to ours have been reported by other investigators on GBS detection in vaginal swabs using a Taqman probe. Eight of 100 samples were positive by real-time PCR alone (specificity 88%), and 1 sample was not detected when compared with culture (sensitivity 92%). Another recent multicenter study on 803 pregnant women reported sensitivities of real-time PCR of 94% (range: 85–99% in different centers) and a specificity of 95.9% (range: 93–100% in different centers).7

Our study has certain limitations. First, because the population of interest was neonates whose maternal GBS status was unknown and who, in most cases, were asymptomatic, neither clinical symptoms nor maternal colonization status could be used as surrogate variables to reconcile discordant results between the culture and real-time PCR. Second, because of the rarity of invasive GBS disease in the newborn, the clinical impact of enhanced detection of GBS colonization by real-time PCR on the incidence of invasive GBS disease could not be demonstrated. In addition, our study included surface site colonization and did not evaluate sterile sites, such as blood or spinal fluid. This was intentionally done with the aim of validating the real-time PCR technique in neonates and as a direct approach to neonatal management in lieu of maternal status. There is recent awareness that documented GBS sepsis may underestimate the true disease burden. Probable early onset GBS disease, defined by a positive ear swab for GBS with clinical pneumonia, meningitis, or sepsis in the absence of an alternative explanation, was reported to have an incidence of 2.5/1000 live births in the United Kingdom.37

The clinical importance of the study is that it validates the novel technique of real-time PCR, under previously established standardized conditions, for the detection of GBS colonization, for the first time in neonates. In the population of essentially asymptomatic neonates whose maternal status is unknown, direct rapid assessment of GBS colonization status is superior to or, at least, adds to risk stratification by maternal status alone. In fact, given recent reports of limitations of antenatal screening cultures, direct rapid assessment of GBS colonization by real-time PCR in the neonate may be preferred to maternal status in determining neonatal management, even in a wider population.

The other impact of the study arises from its excellent negative predictive value. Despite the enhanced sensitivity of real-time PCR that would detect even mild degrees of GBS colonization, ~50% of neonates born to women with an unknown GBS status at delivery would be negative. This subgroup would need no additional testing, hospital observation, or empiric antibiotics. The obvious advantage of the technique is that results would be available in ~1 hour and that it is noninvasive and relatively easy to perform. Of course, its feasibility and cost-effectiveness in clinical settings needs to be evaluated further, because the test would have to be available at all times at considerable institutional expense.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, the real-time PCR is a sensitive rapid method for detection of GBS colonization in neonates. It seems to be a promising and clinically useful screening technique in the appropriate cost-effective management of neonates born to women with an unknown GBS status at delivery. Additional clinical trials are warranted to evaluate its use in other high-risk groups, such as preterm neonates, as well as late-onset infections with GBS.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by the Neonatal Research Endowment, the Sarnaik Endowment for Resident and Fellow Research at Children’s Hospital of Michigan, De-troit, and the National Institutes of Health grants NIDCR 1 RO1 DE 15990, NIH CA 70923, DAMD 17-00-1-0288, and DAMD 17-02-1-0406 (awarded to Dr Worsham).

The technical assistance of Lucille Grietsell, NNP, in recruitment of patients and sample collection is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

References

- 1.Schrag SJ, Zywicki S, Farley MM, et al. Group B streptococcal disease in the era of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:15–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200001063420103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Early-onset group B streptococcal disease–United States, 1998 –1999. JAMA. 2000;284:1508–1510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diminishing racial disparities in early-onset neonatal group B streptococcal disease–United States, 2000–2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53:502–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.ACOG Committee Opinion. Prevention of early-onset group B streptococcal disease in newborns. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:1405–1412. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02629-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schrag S, Gorwitz R, Fultz-Butts K, Schuchat A. Prevention of perinatal group B streptococcal disease. Revised guidelines from CDC. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2002;51:1–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yancey MK, Schuchat A, Brown LK, Ventura VL, Markenson GR. The accuracy of late antenatal screening cultures in predicting genital group B streptococcal colonization at delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;88:811–815. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(96)00320-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davies HD, Miller MA, Faro S, Gregson D, Kehl SC, Jordan JA. Multicenter study of a rapid molecular-based assay for the diagnosis of group B Streptococcus colonization in pregnant women. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:1129–1135. doi: 10.1086/424518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bergeron MG, Ke D, Menard C, et al. Rapid detection of group B streptococci in pregnant women at delivery. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:175–179. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200007203430303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schrag SJ, Zell ER, Lynfield R, et al. A population-based comparison of strategies to prevent early-onset group B streptococcal disease in neonates. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:233–239. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schuchat A. Epidemiology of group B streptococcal disease in the United States: shifting paradigms. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:497–513. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.3.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boyer KM, Gadzala CA, Burd LI, Fisher DE, Paton JB, Gotoff SP. Selective intrapartum chemoprophylaxis of neonatal group B streptococcal early-onset disease. I. Epidemiologic rationale. J Infect Dis. 1983;148:795–801. doi: 10.1093/infdis/148.5.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morven SE, Baker CJ. Group B streptococcal infections. In: Remington JS, Klein JO, eds. Infectious Diseases of the Fetus and Newborn 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders Co; 2001: 1091–1156.

- 13.Boyer KM, Gotoff SP. Prevention of early-onset neonatal group B streptococcal disease with selective intrapartum che-moprophylaxis. N Engl J Med. 1986;314:1665–1669. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198606263142603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palmer AL, Leos NK, Hall M, Jackson GL, Sanchez PJ. Evaluation of suprapubic bladder aspiration for detection of group B streptococcal antigen by latex agglutination in neonatal urine. Am J Perinatol. 1996;13:235–239. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-994371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poilane I, Adam MN, Torlotin JC, Collignon A. Evaluation of a rapid agglutination test for detection of group B streptococci in the gastric aspirates of neonates. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1995;14:815–817. doi: 10.1007/BF01691001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ke D, Menard C, Picard FJ, et al. Development of conventional and real-time PCR assays for the rapid detection of group B streptococci. Clin Chem. 2000;46:324–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pals G, Pindolia K, Worsham MJ. A rapid and sensitive approach to mutation detection using real-time polymerase chain reaction and melting curve analyses, using BRCA1 as an example. Mol Diagn. 1999;4:241–246. doi: 10.1016/s1084-8592(99)80027-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arkin CF, Wachtel MS. How many patients are necessary to assess test performance? JAMA. 1990;263:275–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fleiss JL. Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions 2nd ed. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1981

- 20.Boivin G, Cote S, Dery P, De Serres G, Bergeron MG. Multiplex real-time PCR assay for detection of influenza and human respiratory syncytial viruses. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:45–51. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.1.45-51.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bredius RG, Templeton KE, Scheltinga SA, Claas EC, Kroes AC, Vossen JM. Prospective study of respiratory viral infections in pediatric hemopoietic stem cell transplantation patients. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23:518–522. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000125161.33843.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Espy MJ, Teo R, Ross TK, et al. Diagnosis of varicella-zoster virus infections in the clinical laboratory by LightCycler PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:3187–9. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.9.3187-3189.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Uy IP, D’Angio CT, Menegus M, Guillet R. Changes in early-onset group B beta hemolytic streptococcus disease with changing recommendations for prophylaxis. J Perinatol. 2002;22:516–522. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7210798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pinto NM, Soskolne EI, Pearlman MD, Faix RG. Neonatal early-onset group B streptococcal disease in the era of intra-partum chemoprophylaxis: residual problems. J Perinatol. 2003;23:265–271. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7210899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Uhl JR, Adamson SC, Vetter EA, et al. Comparison of Light-Cycler PCR, rapid antigen immunoassay, and culture for detection of group A streptococci from throat swabs. J Clin Micro-biol. 2003;41:242–249. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.1.242-249.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Espy MJ, Uhl JR, Mitchell PS, et al. Diagnosis of herpes simplex virus infections in the clinical laboratory by LightCycler PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:795–799. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.2.795-799.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sloan LM, Hopkins MK, Mitchell PS, et al. Multiplex LightCy-cler PCR assay for detection and differentiation of Bordetella pertussis and Bordetella parapertussis in nasopharyngeal specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:96–100. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.1.96-100.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen FH, Samson KT, Chen H, et al. Clinical applications of real-time PCR for diagnosis and treatment of human cytomeg-alovirus infection in children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2004;15:210–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2004.00131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bryant PA, Li HY, Zaia A, et al. Prospective study of a real-time PCR that is highly sensitive, specific, and clinically useful for diagnosis of meningococcal disease in children. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:2919–2925. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.7.2919-2925.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matorras R, Garcia-Perea A, Omenaca F, Diez-Enciso M, Mad-ero R, Usandizaga JA. Intrapartum chemoprophylaxis of early-onset group B streptococcal disease. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1991;40:57–62. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(91)90045-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Puopolo KM, Madoff LC, Eichenwald EC. Early-onset group B streptococcal disease in the era of maternal screening. Pediatrics. 2005;115:1240–1246. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ostroff RM, Steaffens JW. Effect of specimen storage, antibiotics, and feminine hygiene products on the detection of group B Streptococcus by culture and the STREP B OIA test. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1995;22:253–259. doi: 10.1016/0732-8893(95)00046-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tichopad A, Didier A, Pfaffl MW. Inhibition of real-time RT-PCR quantification due to tissue-specific contaminants. Mol Cell Probes. 2004;18:45–50. doi: 10.1016/j.mcp.2003.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Warren DK, Liao RS, Merz LR, Eveland M, Dunne WM., Jr Detection of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus directly from nasal swab specimens by a real-time PCR assay. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:5578–5581. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.12.5578-5581.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huletsky A, Giroux R, Rossbach V, et al. New real-time PCR assay for rapid detection of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus directly from specimens containing a mixture of staphylococci. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:1875–1884. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.5.1875-1884.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bergh K, Stoelhaug A, Loeseth K, Bevanger L. Detection of group B streptococci (GBS) in vaginal swabs using real-time PCR with TaqMan probe hybridization. Indian J Med Res. 2004;119(suppl):221–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luck S, Torny M, d’Agapeyeff K, et al. Estimated early-onset group B streptococcal neonatal disease. Lancet. 2003;361:1953–1954. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13553-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]