Abstract

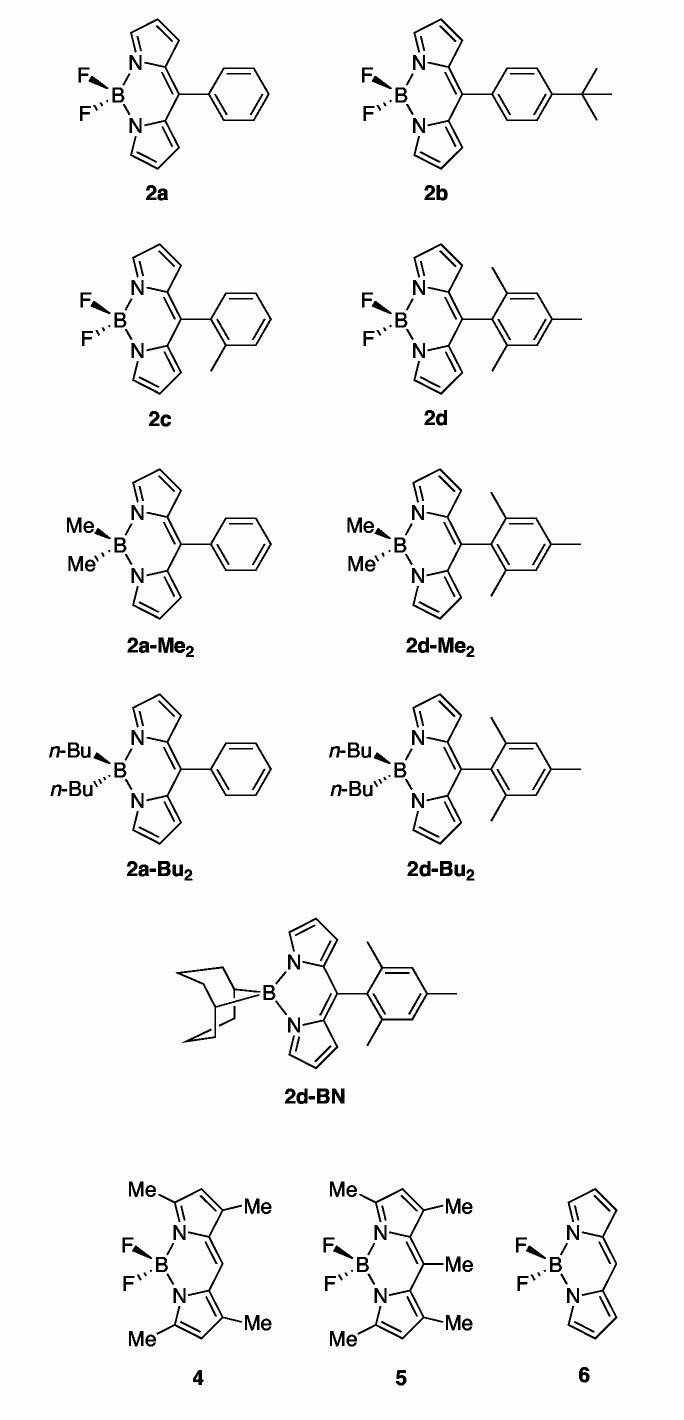

Boron-dipyrrin chromophores containing a 5-aryl group with or without internal steric hindrance toward aryl rotation have been synthesized and then characterized via X-ray diffraction, static and time-resolved optical spectroscopy, and theory. Compounds with a 5-phenyl or 5-(4-t-butylphenyl) group show low fluorescence yields (∼0.06) and short excited-singlet-state lifetimes (∼500 ps), and decay primarily (>90%) by nonradiative internal conversion to the ground state. In contrast, sterically hindered analogues having an o-tolyl or mesityl group at the 5-position exhibit high fluorescence yields (∼0.9) and long excited-state lifetimes (∼6 ns). The X-ray structures indicate that the phenyl or 4-tert-butylphenyl ring lies at an angle of ∼60°with respect to the dipyrrin framework whereas the angle is ∼80°for mesityl or o-tolyl groups. The calculated potential energy surface for the phenyl-substituted complex indicates that the excited state has a second, lower energy minimum in which the non-hindered aryl ring rotates closer to the mean plane of the dipyrrin, which itself undergoes some distortion. This relaxed, distorted excited-state conformation has low radiative probability as well as a reduced energy gap from the ground state supporting a favorable vibrational overlap factor for nonradiative deactivation. Such a distorted conformation is energetically inaccessible in a complex bearing the sterically hindered o-tolyl or mesityl group at the 5-position, leading to a high radiative probability involving conformations at or near the initial Franck-Condon form of the excited state. These combined results demonstrate the critical role of aryl-rotation in governing the excited-state dynamics of this class of widely used dyes.

Introduction

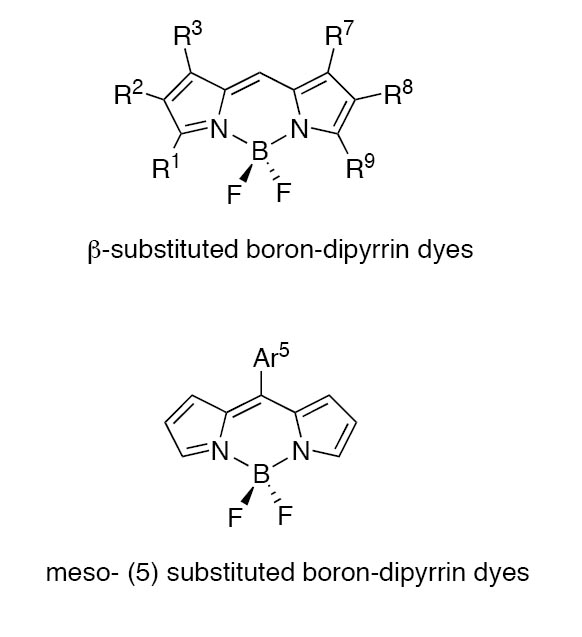

Boron-dipyrrin dyes were first discovered by Treibs and Kruezer in 1968.1 Since then, boron-dipyrrin dyes have been widely used as markers in life-sciences research.2 One limitation to the even broader use of boron-dipyrrin dyes has been the construction of the dipyrrin chromophore using β-substituted pyrrole units (Chart 1), which are available only via quite lengthy synthetic procedures. A decade ago we discovered a simple entrée into 5-substituted dipyrromethanes by reaction of an aldehyde with excess pyrrole at room temperature,3 and have since refined this simple procedure.4,5 Dolphin showed that such dipyrromethanes can be oxidized to the corresponding free base dipyrrins upon treatment with DDQ or p-chloranil.6 Complexation of a free base dipyrrin with BF3·O(Et)2 in the presence of TEA yields the desired boron-dipyrrin complex.

chart 1

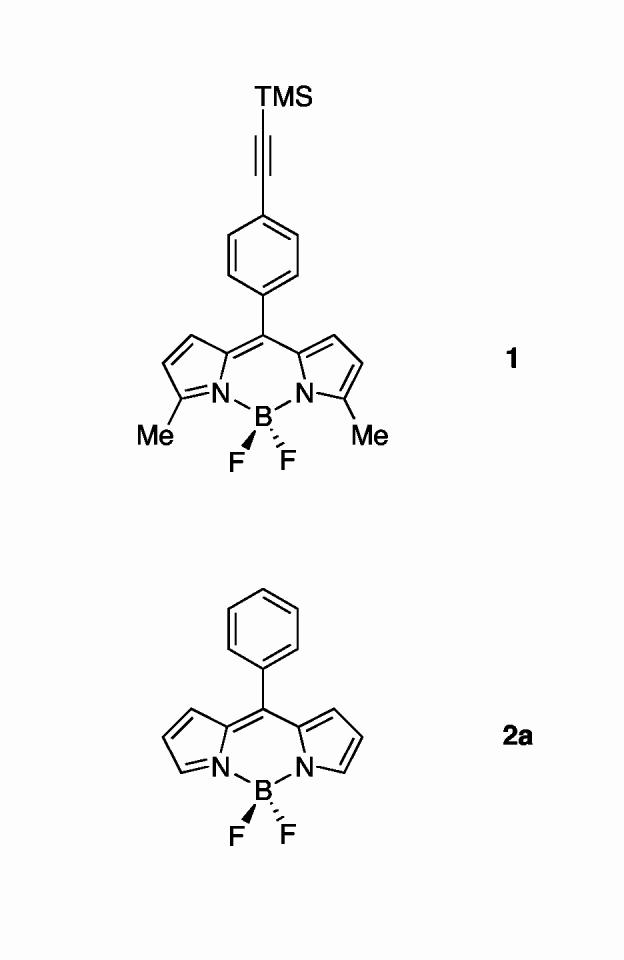

We initially synthesized a boron-dipyrrin dye that incorporated an aryl group at the 5-position and a methyl group at each of the pyrrolic α-positions (1, Chart 2).7,8 Such dyes were incorporated in a variety of architectures, including a molecular photonic wire,7,9 an optoelectronic gate,10 and a light-harvesting array.11 To our surprise, 5-substituted boron-dipyrrin dyes were only weakly fluorescent (Φf = 0.058 for 1), in contrast to the intense fluorescence of the analogous β-substituted dipyrrins first prepared by Treibs and widely used in the life sciences. Time-resolved studies showed that the 5-aryl-substituted dyes exhibited rather short singlet-excited-state lifetime of ∼500 ps, with an even faster ∼15 ps component to the excited-state relaxation dynamics.11 Ab initio calculations indicated that the two kinetic components are associated with two energetically accessible conformers that differ in the rotation of the 5-aryl group and in distortions of the boron-dipyrrin framework. The aryl-ring rotation and accompanying chromophore distortions allow access to an excited-state conformer with low radiative probability and facile nonradiative deactivation to the ground state, thereby limiting the fluorescence yields of the dyes.11 The fluorescence properties of an unsubstituted analogue of 1, which contained only the 5-phenyl group (2a), also exhibited a low fluorescence quantum yield (Φf = 0.053).8

chart 2

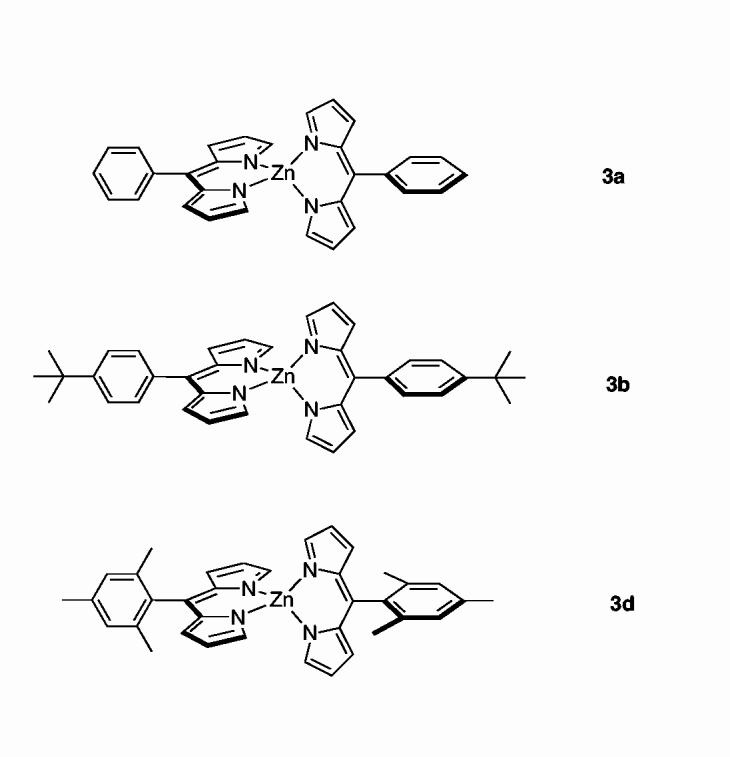

More recently, we have prepared and characterized a series of bis(dipyrrinato)zinc(II) complexes (Chart 3).12 The complex with a 5-phenyl group (3a) exhibits a very short excited-state lifetime (90 ps) and a low fluorescence quantum yield (0.006). By contrast, the complex with a 5-mesityl group (3d) exhibits a normal excited-state lifetime (∼3 ns) and much larger fluorescence quantum yield (0.36).13 The photophysical behavior of complex (3b), which contains a 4-tert-butylphenyl group but lacks the 2,6-dimethyl groups, resembles complex 3a, indicating that electronic effects are not the source of the altered excited-state behavior. The profound increase in excited-state lifetime is attributed to steric inhibition of rotation of the 5-mesityl group by the mesityl o-methyl substituents. This striking result has prompted us to revisit the boron-dipyrrin complexes with a particular focus on the role of steric effects in controlling the photodynamics of this class of dyes.

chart 3

In this paper, we describe the synthesis and structural, photophysical, and theoretical characterization of a series of boron complexes of 5-substituted dipyrrin dyes. The substituents include phenyl, 4-tert-butylphenyl, o-tolyl, and mesityl (2a-d, Chart 4). The boron-dipyrrin dyes 2a-d are more readily synthesized than the corresponding dyes (4, 5) bearing substituents at the pyrrolic β-positions. We also synthesized and studied five analogs bearing alkyl groups rather than fluorine atoms on the boron (2a-Me2, 2a-Bu2, 2d-Me2, 2d-Bu2, 2d-BN). The fully unsubstituted dye (6), although unknown, is a benchmark for theoretical calculations.

chart 4

Results and Discussion

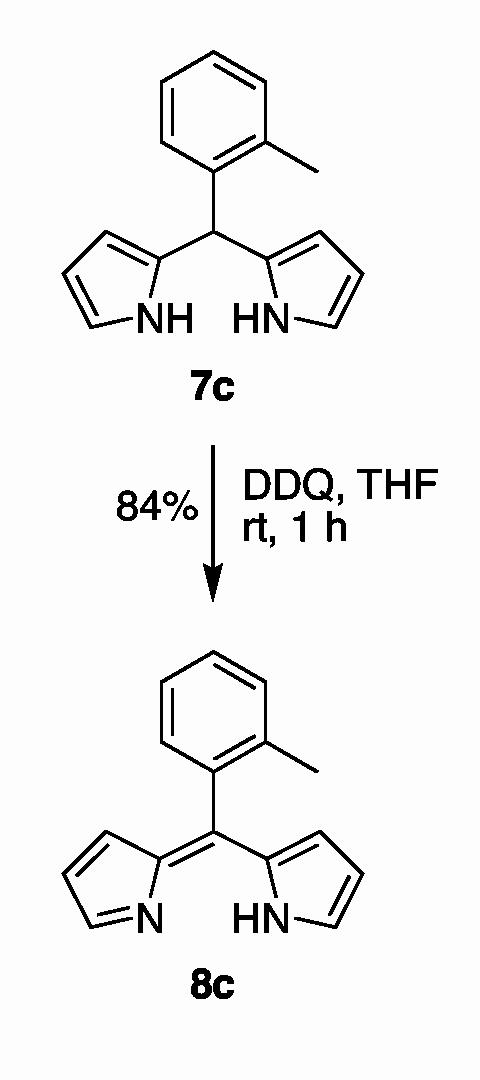

Synthesis. The synthesis of the boron-dipyrrin dyes requires access to the corresponding dipyrrin, which is obtained in turn from the dipyrromethane (7). The oxidative conversion of a dipyrromethane to a dipyrrin can be performed with DDQ or p-chloranil in THF.6,12 Dipyrrins 8a, 8b, and 8d have been prepared previously.12 The synthesis of dipyrrin 8c is shown in Scheme 1. Treatment of 5-(o-tolyl)dipyrromethane (7c)4 with DDQ in THF afforded dipyrrin 8c in 84% yield.

scheme 1

Boron-dipyrrin complexes such as 2a were prepared previously from the dipyrromethane (without isolation of the dipyrrin) via a two-step one-flask reaction.4,8,11 Here we have employed excess TEA and BF3·O(Et)2 to complete the reaction (Scheme 2). Thus, treatment of a free base dipyrrin 8 with TEA and BF3·O(Et)2 (10 molar equivalents each) in CH2Cl2 at room temperature for 30 min afforded the desired boron-dipyrrin complex 2 in fair yield (19-68%). Each boron-dipyrrin complex (2a-d) is less polar than the corresponding starting material (8) or other byproducts and could be easily separated via flash column chromatography. In this manner, boron-dipyrrin complexes 2a-d were obtained.

scheme 2

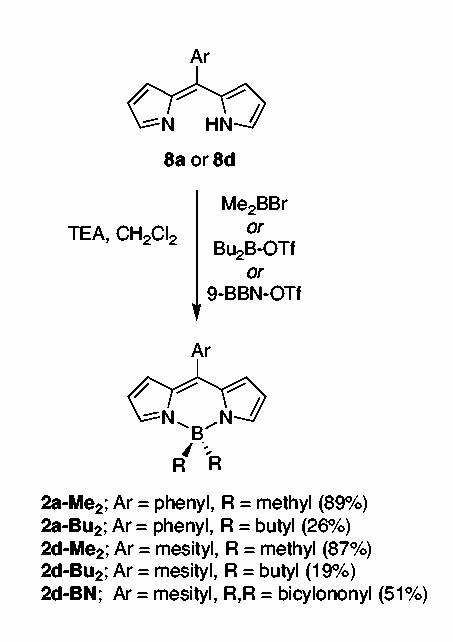

A series of dialkylboron analogs was prepared in similar fashion. The reaction of dipyrrin 8a with bromodimethylborane or dibutylboron triflate afforded 2a-Me2 or 2a-Bu2, respectively. The reaction of 5-mesityldipyrrin (8d) with bromodimethylborane, dibutylboron triflate, or 9-BBN triflate afforded 2d-Me2, 2d-Bu2, or 2d-BN, respectively. Each compound was isolated by chromatography on silica and was stable to routine handling.

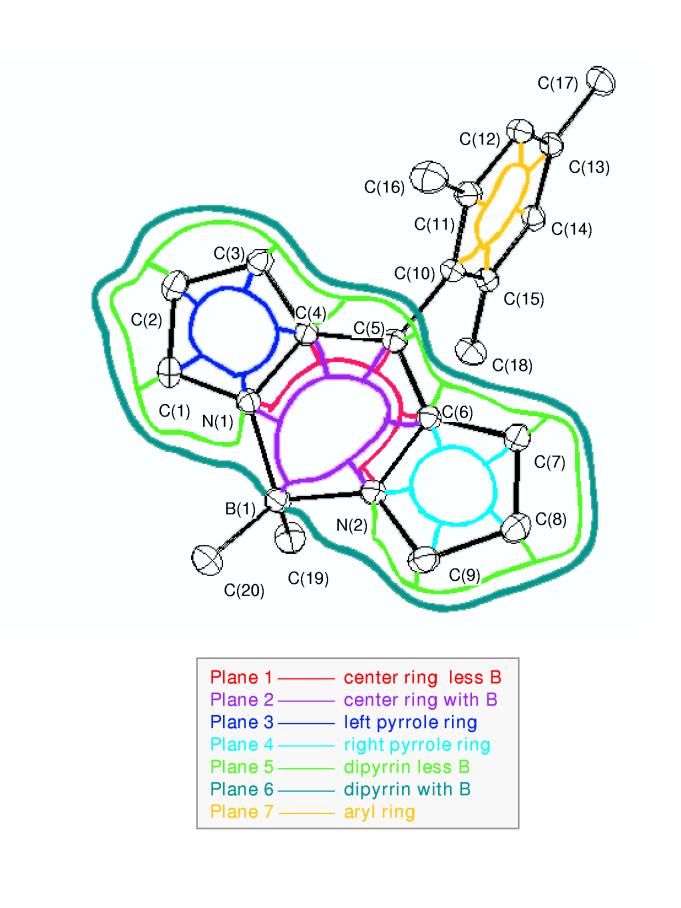

Structural studies. The results of X-ray diffraction studies of five boron-dipyrrin compounds are described in the Supporting Information. The principal effects of the 5-aryl group and boron substituent can be seen in Table 1 and Figure 1, which give the dihedral angles between various mean planes in the architectures. In all five compounds, the boron-dipyrrin framework, which encompasses the two pyrrole rings and the central six-member ring containing the boron atom, is essentially planar. For the four compounds with fluorines on the boron, the deviation of the pyrrole planes with respect to each other and the central ring is typically only a few degrees. Somewhat larger (but still very modest) deviations are observed in 2d-Me2, in which methyl groups replace fluorine atoms on boron. In this case, the dipyrrin framework is slightly puckered, as indicated by the ∼15°dihedral angle between the two pyrrole rings (planes 3 and 4 in Figure 1 and Table 1). For all five compounds, some of the small deviations from coplanarity of the planes in the dipyrrin framework may reflect the effects of crystal packing forces. One example may be the effects of replacement of the 5-phenyl ring in 2a with the 4-tert-butylphenyl ring in 2b.

Table 1.

Dihedral angles between planes in boron-dipyrrin dyes.

| plane | 5-group:a B-group:b | 2a phenyl F | 2bt-Bu-phenyl F | 2d mesityl F | 2co-tolyl F | 2d-Me2 mesityl Me |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1,2 | 0.0 | 2.9 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 5.7 | |

| 1,3 | 1.9 | 7.0 | 1.7 | 2.5 | 7.1 | |

| 2,3 | 1.9 | 6.4 | 1.0 | 2.9 | 8.9 | |

| 1,4 | 1.9 | 1.0 | 2.7 | 2.9 | 8.4 | |

| 2,4 | 1.9 | 3.9 | 3.1 | 2.8 | 8.8 | |

| 3,4 | 2.6 | 7.7 | 3.4 | 5.4 | 15.3 | |

| 1,5 | 0.7 | 1.6 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.3 | |

| 2,5 | 0.7 | 3.2 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 5.7 | |

| 3,5 | 1.5 | 5.5 | 1.6 | 2.5 | 7.4 | |

| 4,5 | 1.5 | 2.2 | 0.1 | 2.9 | 8.2 | |

| 1,6 | 0.7 | 2.7 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 4.3 | |

| 2,6 | 0.7 | 1.7 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 1.4 | |

| 3,6 | 1.5 | 4.9 | 1.1 | 2.8 | 8.4 | |

| 4,6 | 1.5 | 3.7 | 2.5 | 2.7 | 8.1 | |

| 5,6 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 4.3 | |

| 1,7 | 60.8 | 50.0 | 75.4 | 84.8 | 84.4 | |

| 2,7 | 60.8 | 50.2 | 75.3 | 84.8 | 84.7 | |

| 3,7 | 2.1 | 56.6 | 75.9 | 2.3 | 77.3 | |

| 4,7 | 62.1 | 49.6 | 77.9 | 7.6 | 92.6 | |

| 5,7 | 61.4 | 51.6 | 76.1 | 84.9 | 84.6 | |

| 6,7 | 61.4 | 51.7 | 71.6 | 84.9 | 84.9 |

Substituent group at the 5-position.

Substituent groups on boron.

Figure 1.

Basic architecture and atom numbering of a 5-aryl-substituted dipyrrin. Planes encompassing a number of architectural features are indicated by the colored lines. The dihedral angles between these planes are given in Table 1.

One of the most pronounced effects of the 5-aryl substituent lies in the dihedral angles between the 5-aryl ring (plane 7) and the planes defining various dipyrrin elements. The angles increase from ∼50°(2b, 4-tert-butylphenyl) and ∼60°(2a, phenyl) when no internal hindrance for aryl rotation is present, to ∼75°(2d, mesityl) and ∼85°(2c, o-tolyl) when this motion is restricted. Steric hindrance also tends to lengthen the C5-C10 bond between the dipyrrin and the aryl group, from 1.478(3) for 2b and 1.4813(11) for 2a to 1.4912(10) for 2d and 1.4944(17) for 2c. These ground-state structural effects are a harbinger of the distortions involving the planarity of the dipyrrin framework and rotation of the aryl ring that may occur in the excited states of the complexes, as is indicated in the photophysical data and theoretical calculations described below.

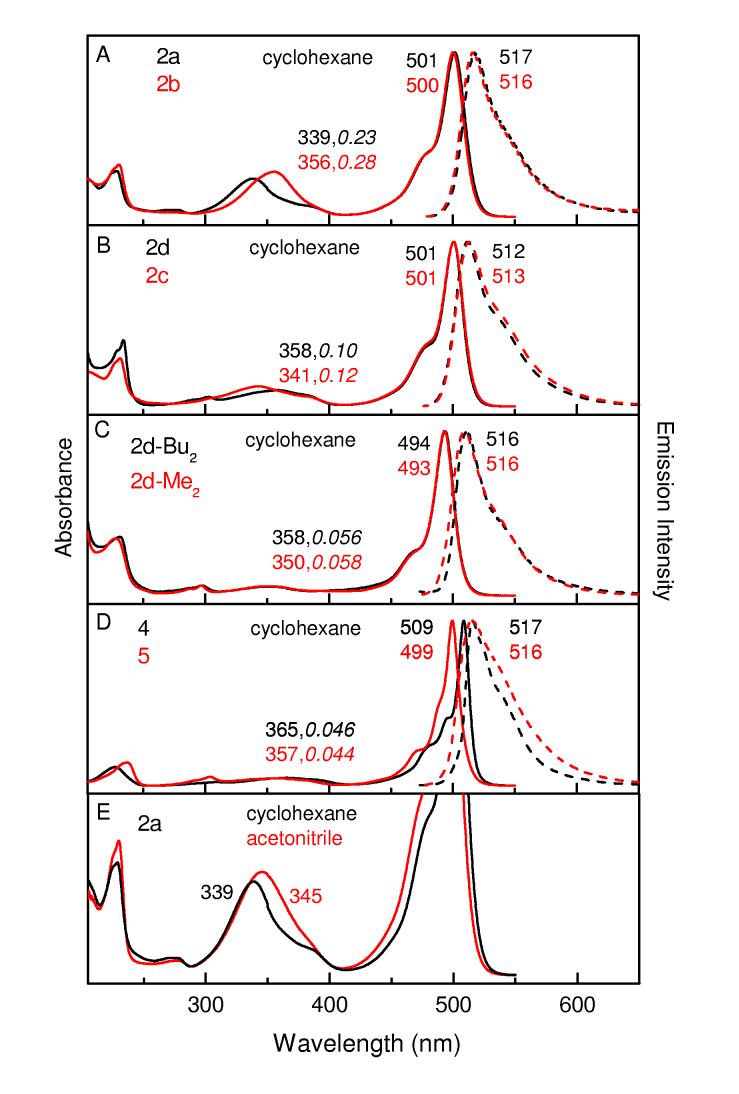

Photophysical characterization. Absorption and Emission Spectra. Figure 2 gives UV/Vis room-temperature electronic ground-state absorption spectra (---) and S1 → S0 fluorescence spectra (- - -) of a series of the boron-dipyrrin complexes in cyclohexane (panels A-D). Generally similar spectra are observed in toluene and acetonitrile, and in a solid polyvinyl acetate (PVA) matrix (Supporting Information). Regardless of the presence or nature of a 5-aryl ring or the boron substituents, all of the spectra contain a S0 → S1 origin band (490-500 nm) and vibronic components spanning ∼25 nm to higher energy. A parallel situation exists in the S1 → S0 fluorescence spectra. These vibronic contours are analyzed theoretically below. There is a significant spacing (Stokes shift) of 500-900 cm-1 between the absorption and emission maxima, indicating excited-state conformational changes, solvent reorientation, or both. One of the most notable changes that occurs in the electronic absorption spectrum upon an increase in solvent polarity from cyclohexane (or toluene) to acetonitrile is alteration of the absorption contour in the region between 300 and 400 nm, which includes an increase in intensity of one of the contributing transitions (cf. Figure 2E).

Figure 2.

Room temperature electronic absorption spectra (solid) and fluorescence spectra(dashed) of boron-dipyrrin dyes. The peak wavelengths are indicated. The second value indicated for the absorption in the 300-400 nm region in panels A-E is the peak amplitude compared to the maximum of the lowest-energy transition in the 490-510 nm region. The fluorescence spectra were acquired using an excitation wavelength of 450-460 nm. The spectra in panel E are vertically enhanced ∼3-fold from the other panels to emphasize the solvent dependence of the spectra in the 300-400 nm region.

Polarized fluorescence and fluorescence-excitation spectra were acquired for 2a in PVA at room temperature (Supporting Information). The excitation spectra obtained using fluorescence detection at 518, 550, or 650 nm give a constant polarization ratio of ∼0.27 over the main absorption profile from 400 to 450 nm. These results are consistent with parallel transition dipoles for these absorption and fluorescence features, which can be understood because common S0↔S1 transitions are involved. On the other hand, the polarization ratio for the weaker absorption feature(s) near 350 nm drops below zero, indicating the absorption transition dipole(s) is aligned more perpendicular to that for the S1 → S0 fluorescence. Generally similar polarization results have been obtained previously for 4.13

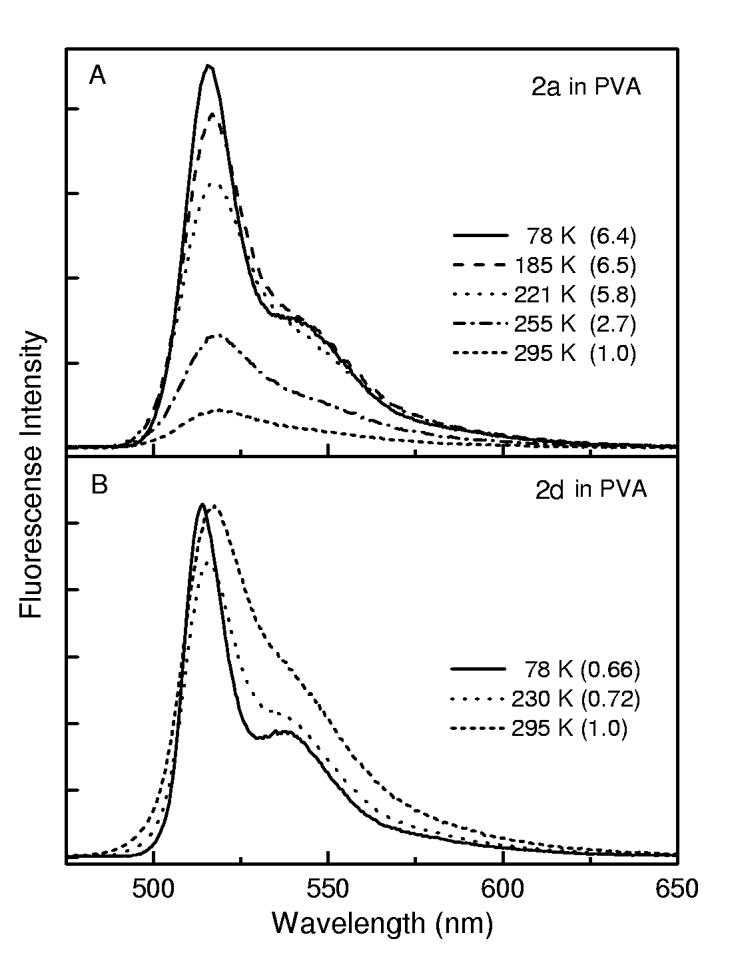

Fluorescence Yields and Lifetimes at Room Temperature. The optical spectra described above indicate that the substituents on the 5-aryl ring of the boron-dipyrrin dyes have only modest impact on the absorption spectra and even less significant effects on the S1 → S0 fluorescence profiles. Nonetheless, the nature of the 5-aryl ring has dramatic effects on the fluorescence quantum yield (Φf) and the lifetime of the S1 excited state (τ), as shown in Table 2. These two quantities are related to the fundamental rate constants for S1 → S0 decay via fluorescence (kf), S1 → S0 internal conversion (kic), and S1 → T1 intersystem crossing (kisc) via the formulas τ = (kf + kic + kisc)-1 and Φf = kf ÷(kf + kic + kisc) = kf • τ. Table 2 gives estimates for the yields of the two nonradiative decay pathways (internal conversion and intersystem crossing) obtained from the transient absorption data described below. This table also gives estimates for the inverse rate constants (i.e., time constants) for the three S1 decay pathways obtained from the excited-state lifetime and corresponding yield via the formula (ki)-1 = τ÷Φi. For comparison, Table 2 gives our prior results for toluene solutions of 2a and 1 (Charts 2),11 along with fluorescence yield and lifetime data for the boron dipyrrins in PVA (and ethylene glycol). These latter studies were undertaken to determine if motional restrictions imposed by the medium would influence the S1 photophysics at room temperature.

Table 2.

Photophysical data for boron dipyrrins.

| Compound | solvent | substituents | τ (ns) | Φf | ΦIC | ΦISC | (kf)-1 (ns) | (kic)-1 (ns) | (kisc)-1 (ns) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | boron | pyrrole | |||||||||

| 2a | toluene | phenyl | F | H | 0.45 | 0.062 | >0.95 | <0.05 | 7.3 | <0.6 | >5 |

| 2aáb | toluene | 0.44 | 0.053 | 8.3 | |||||||

| 2a | PVA | 1.2 | 0.12 | 11 | |||||||

| 2b | toluene | t-Buφ | F | H | 0.55 | 0.069 | >0.95 | <0.05 | 8.0 | <0.6 | >5 |

| 2b | PVA | 1.1 | 0.10 | 10 | |||||||

| 2b | ethyne glycol | 0.68 | 0.045 | 11 | |||||||

| 2c | toluene | o-tolyl | F | H | 5.8 | 0.93 | <0.07 | <0.05 | 6.2 | >70 | >100 |

| 2c | PVA | 6.1 | 0.90 | 6.8 | |||||||

| 2d | toluene | mesityl | F | H | 6.6 | 0.93 | <0.07 | <0.05 | 7.1 | >70 | >100 |

| 2d | PVA | 6.8 | 0.89 | 7.8 | |||||||

| 2d-Me2 | toluene | mesityl | Me | H | 3.7 | 0.40 | 9.3 | ||||

| 4 | toluene | H | F | Me | 6.1 | 0.92 | <0.08 | <0.05 | 6.6 | >70/ | >100 |

| 5 | toluene | Me | F | Me | 5.6 | 0.93 | <0.07 | <0.05 | 6.0 | >70 | >100 |

| 1a | toluene | b | F | c | 0.52 | 0.058 | >0.95 | <0.05 | 9.0 | <0.6 | >5 |

From ref. 11.

TMS-terminated phenylethyne.

methyl groups only at the 1,9-positions (adjacent to pyrrole nitrogens).

The fluorescence quantum yield found here for phenyl-substituted boron dipyrrin 2a in toluene (Φf = 0.062) is in good agreement with our earlier value (0.053).11 We also obtained the same excited-state lifetime determined by fluorescence decay (τ = 0.45 ns). Very similar results are obtained for the 4-tert-butylphenyl analogue 2b (Φf = 0.069, τ = 0.55 ns). In contrast, the introduction of steric constraints on the aryl rings causes bright emission and long excited-state lifetimes. In particular, the o-tolyl-substituted complex 2c in toluene has Φf = 0.93 and τ = 5.8 ns, and the mesityl analogue 2d has Φf = 0.93 and τ = 6.6 ns. Interestingly, relatively strong fluorescence was also observed for 2d-Me2 (Φf = 0.40 and τ = 4.0 ns), which contains methyl groups in place of hydrogen atoms on boron. On the other hand, the fluorescence quantum yield declined markedly upon increasing steric bulk at the boron atom [2d-Bu2, Φf = 0.034, τ = 3.4 ns; 2d-BN, Φf = 0.004]. Quite low fluorescence yield was observed with the dialkylboron analogs of the phenyl-substituted dipyrrin [2a-Me2, Φf = 0.008; 2a-Bu2, Φf = 0.008]. The differences in fluorescence behavior may derive from motions involving the alkyl groups; however, these compounds are somewhat unstable under prolonged illumination and were not studied in detail.In agreement with previous results,14-17 intense fluorescence and long excited-state lifetimes are also obtained for 4 and 5, which contain fluorine atoms on boron, hydrogen or methyl groups (rather than an aryl substituent) at the 5-position along, and methyl groups on the pyrrole rings (Table 2). The fluorescence lifetimes and yields (in toluene) for all of the boron-dipyrrin complexes listed in Table 2 give a radiative rate constant in the range kf = (6-10 ns)-1.

These findings indicate that the low emission yields and short excited-state lifetimes found in aryl-substituted complexes bearing no internal steric hindrance derive from a facile S1-excited-state nonradiative decay channel that is restricted when internal steric constraints are imposed (or in the absence of a 5-aryl ring). As is shown below from the transient absorption data and theoretical results, these low emission yields and short S1 excited-state lifetimes result from excited-state conformational changes that drive fast internal conversion to the ground state. In addition to internal steric hindrance, these motions also can be restricted by external forces. For example, Table 2 shows that the fluorescence yield and lifetime essentially double for 2a when the medium is changed from toluene solution (Φf = 0.062, τ = 0.45 ns) to the solid PVA matrix (0.1, 1.1 ns) at room temperature. The same effect is observed for 2b in toluene (0.069, 0.55 ns) versus PVA (0.1, 1.1 ns) and intermediate results are observed in ethylene glycol, which has intermediate viscosity (Table 2). By contrast with the sterically unhindered 2a and 2b, the respective mesityl and o-tolyl complexes 2d and 2c, which have internal steric hindrance to aryl rotation, show virtually no change with medium viscosity, namely fluorescence yields of 0.89-0.93 and lifetimes of 5.8-6.9 ns in both toluene and PVA. Parallel but even more dramatic effects on the fluorescence properties of dipyrrins with and without internal steric hindrance to 5-aryl rotation are found with temperature, as is described in the following.

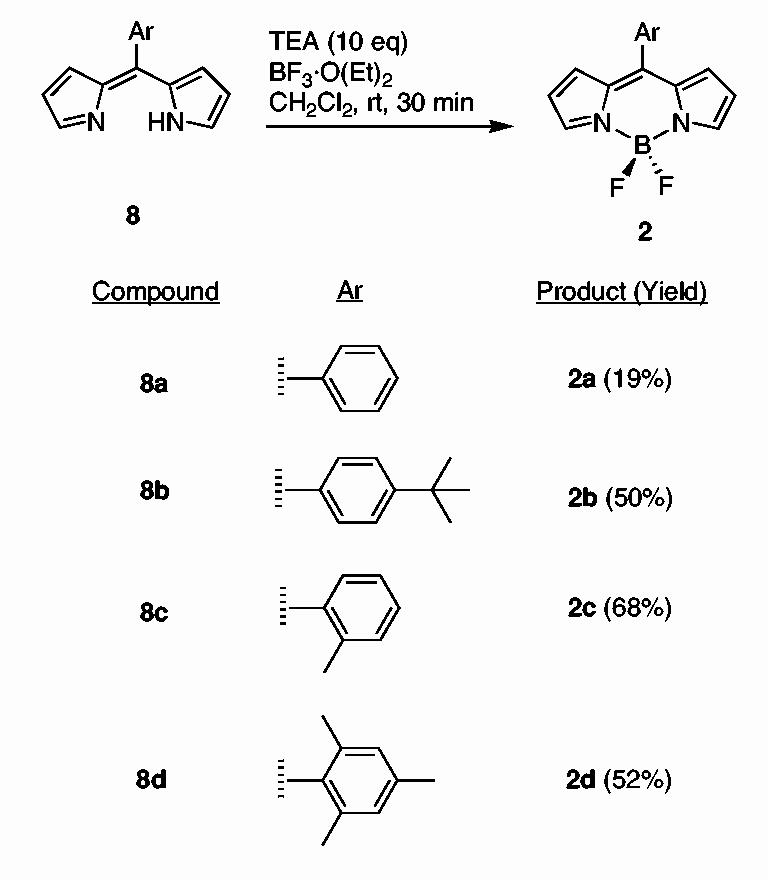

Temperature Dependence of the Fluorescence Yield. The effect of temperature on the fluorescence behavior of the phenyl-substituted complex 2a was examined in parallel with the mesityl-substituted analogue 2d. Solid PVA was used as the medium in both cases because (1) PVA is transparent across the temperature range studied (295 to 78 K), (2) discontinuities at the freezing point of a solution sample are avoided, and (3) changes in viscosity with temperature are small compared to a solution sample, affording a more clear effect of temperature (thermal energy). Figure 3 shows the results. The integrated fluorescence of unhindered 2a in PVA increases about 6-fold when the temperature is lowered from 295 to 78 K. In contrast, the emission from hindered 2d appears to increase slightly with the same reduction in temperature. [There is little (<20%) temperature dependence of the absorbance at the 450 or 455 nm excitation wavelength in either sample.]

Figure 3.

Temperature dependence of the fluorescence for 2a (A) and 2d (B) in PVA. The samples were excited at 455 or 450 nm, respectively.

An apparent activation energy on the order of 1000 cm-1 is obtained from an Arrhenius analysis. It must be born in mind that this activated phenomenon may not simply reflect the energy for photoexcited 2a to surmount a barrier for phenyl rotation. Instead, this is likely to represent a rather low-energy torsional motion (< 50 cm-1), coupled with nonplanar distortion of the dipyrrin framework. These low-energy motions are no doubt populated to very high quantum levels, especially at ambient temperature. Hence the apparent activation energy may represent in part the quantum-level dependence of tunneling through a torsional barrier, and not an actual barrier crossing.

Regardless of the precise physical significance of the apparent activation energy, the key finding is that the fluorescence yield of the phenyl-substituted boron dipyrrin lacking internal steric constraint (2a) increases significantly when thermal energy is reduced. The value at 78 K (Φf ∼0.35) has climbed to 30-50% of that of the mesityl-substituted analogue, which contains internal hindrance to aryl-ring rotation (2d). These observations are another indication that excited-state conformation excursions are a key process in driving the observed fluorescent behavior of aryl-substituted boron-dipyrrin dyes.

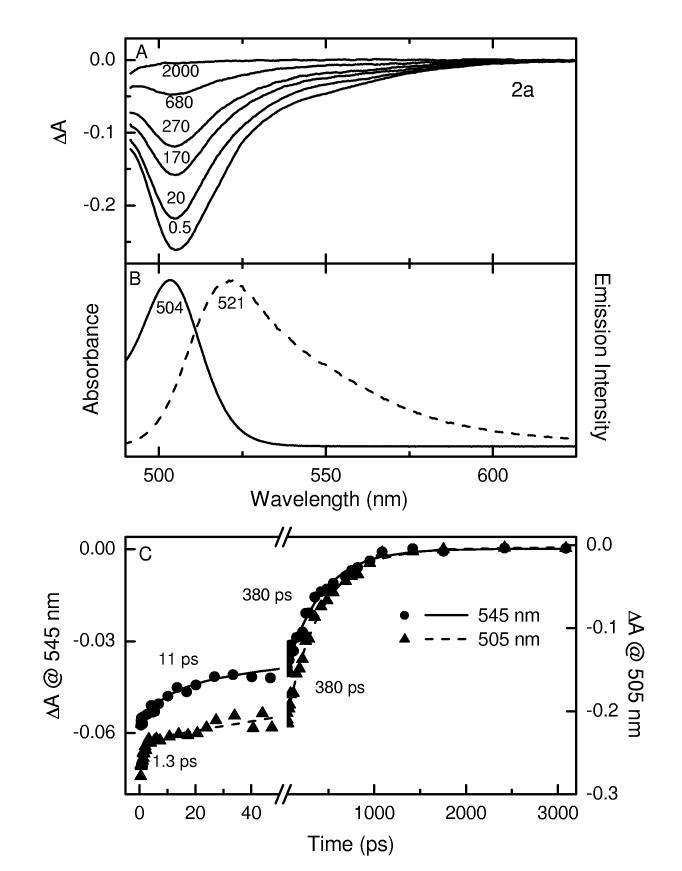

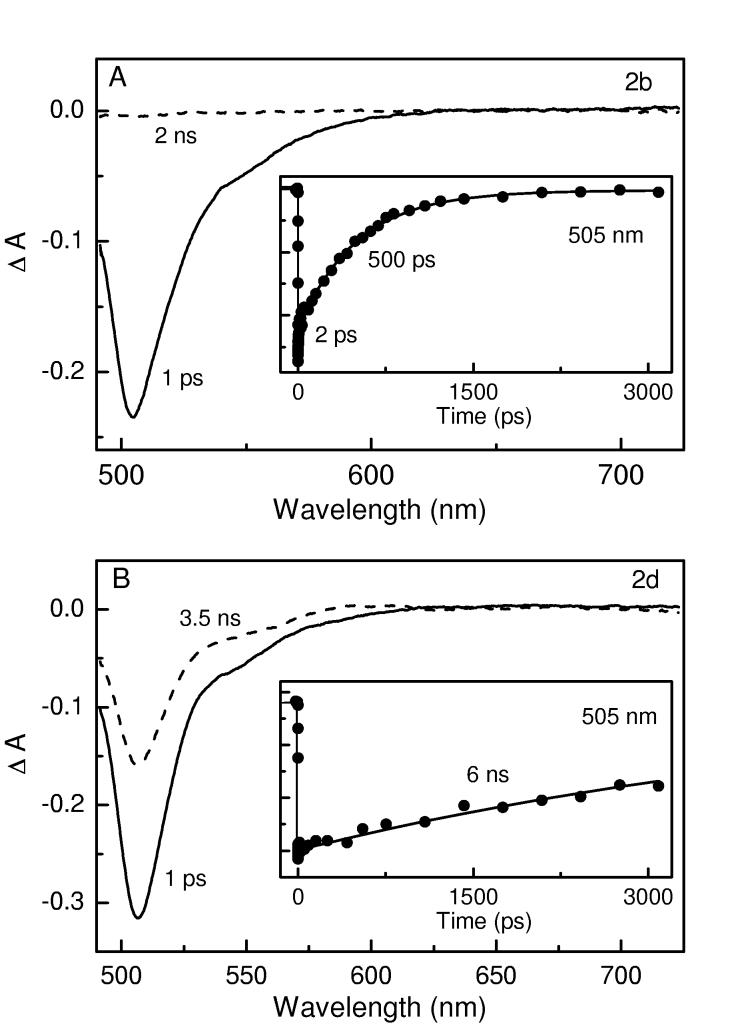

Transient Absorption Spectra and Kinetics. Figures 4 and 5 give representative transient absorption spectra and kinetic data for 2a, 2b, and 2d in toluene at room temperature, employing ∼100 fs excitation flashes at ∼485 nm. Additional data are given in the Supporting Information. Comparison with the static absorption (solid) and fluorescence (dashed) spectra for 2a in Figure 4B indicates that the transient absorption difference spectra in Figure 4A are comprised of bleaching of the S0 → S1 ground-state absorption band at ∼505 nm plus a tail to longer wavelengths representing S1 → S0 stimulated emission (i.e., gain in the white-light probe pulse in the fluorescence region). The spectra have decayed completely to the ΔA = 0 baseline by 2 ns, indicating complete deactivation to the ground state and insignificant formation of a longer-lived metastable state such as the triplet (T1) excited state. Given the very small fluorescence yield (∼0.06, Table 2), these combined data indicate that the decay of photoexcited 2a in toluene occurs predominantly by S1 → S0 nonradiative internal conversion.

Figure 4.

Time-resolved absorption difference spectra for 2a in toluene at room temperature using ∼100 fs excitation flashes at 483 nm (A); the time (in picoseconds) for each spectrum is indicated. Absorption (solid) and fluorescence (dashed) spectra for this compound (B). Representative kinetic traces and dual-exponential fits at 505 nm (ground-state absorption bleaching decay) and 545 nm (stimulated emission decay) are shown in panel C.

Figure 5.

Time-resolved absorption and kinetic data (at 505 nm) for 2b (A) and 2a (B). Other conditions are as in Figure 4.

The kinetic traces in Figure 4C show a major (>70%) component with a time constant of ∼400 ps to the decay of both ground state bleaching (505 nm) and stimulated emission (545 nm); this value agrees well with the S1 lifetime of 0.45 ns observed via fluorescence decay (Table 2). The decay of ground-state-absorption bleaching also shows a component with a time constant of ∼1 ps along with a contribution from a third phase having a time constant of ∼ 10 ps. The ∼10 ps phase also contributes in the stimulated-emission region. Thus, these two fast phases represent a combination of rapid deactivation to the ground state (in addition to the dominant 380 ps phase) and conformational evolution on the S1 surface with consequent spectral changes. These results corroborate the biphasic kinetics observed previously for 2a and 1 in toluene,11 and reveal at least one additional contribution to the excited-state dynamics.

Similar results to those found for the phenyl-substituted complex 2a are also observed for the 4-tert-butylphenyl analogue 2b (Figure 5A). In particular, deactivation to the ground state is complete by 2 ns, and occurs predominantly with a time constant of 500 ps that is in good agreement with the value (0.55 ns) obtained by fluorescence decay (Table 2). In contrast, a much longer deactivation time is observed for the mesityl-substituted 2d (Figure 5B). For this complex, the ground-state recovery is only about one-half complete by 3.5 ns. When the decay profile observed over the ∼4 ns limit of this spectrometer is fit to an exponential decay function containing ΔA = 0 at long-time asymptote (either fixed or in a free fit), a time constant of ∼6 ns is obtained. This value is in good agreement with the S1 lifetime of 6.6 ns observed by fluorescence decay. These combined results indicate that the S1 decay for 2d leads predominantly to repopulation of the ground state with little triplet formation. This result is expected since the fluorescence yield of this compound of 0.93, which returns the excited molecules to the ground state via this emissive route.

Thus, the transient absorption data are fully consistent with the results of the static spectroscopy and fluorescence lifetime measurements and indicate that the S1 excited state of sterically hindered boron dipyrrins 2d (and 2c) decay predominantly (≥90%) by fluorescence emission whereas the unhindered analogues 2a (and 2b) deactivate predominantly (≥90%) by nonradiative internal conversion to the ground state.

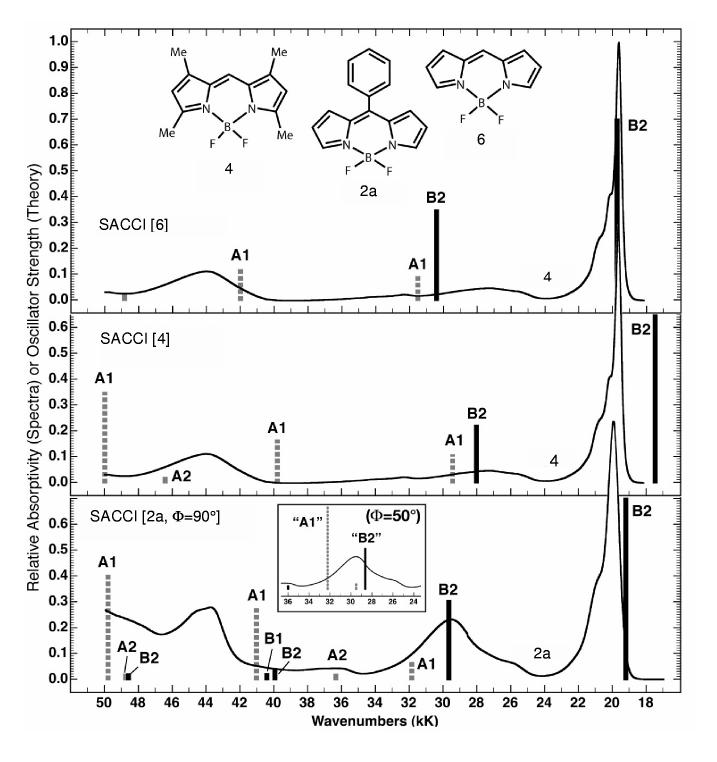

Theoretical Analysis. Nature of the Lowest Excited Singlet States and Assignment of the Optical Transitions. The energies of the excited states of the boron-dipyrrin dyes were calculated using the symmetry-adapted cluster configuration interaction (SACCI) method. A comparison of the SACCI excited singlet state manifolds with the absorption spectra of 4 and 2a is shown in Figure 6. In general, SACCI with single and double configuration interaction reproduces the absorption spectra of these compounds. The results support the notion that the lowest-lying excited singlet state is a strongly allowed B2 or B2-like state. As shown in the state correlation diagram (Figure 7), the ordering of the lowest three excited singlet states (B2, 1A1,2B2) is not sensitive to substitution and aryl rotation. However, the position of the 2A1 excited state is very sensitive to rotation of the aryl ring. When this ring is phenyl and is rotated to the minimum energy position (Φ = 50°), the 2A1 state drops dramatically (∼10 kK) in energy as shown in the insert in the bottom panel of Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Comparison of the absorption spectra of 4 (top two spectra) and 2a (lower spectrum) with the calculated singlet state transition energies for 6, 4 and 2a with the phenyl group rotated orthogonal to the boron-dipyrrin plane. The ground-state geometries were optimized using B3LYP/6-31G(d) methods and the spectroscopic properties were calculated using SACCI methods with single and double CI (see text). The heights of the bands are proportional to the oscillator strengths of the bands. Forbidden or very weak bands are assigned an oscillator strength of 0.04 so that the band is visible.

Figure 7.

Comparison of the excited-state level ordering in 6, 4, 2a-Bu2 and 2a on the basis of SACCI methods including single and double CI (see text). The oscillator strengths for low-lying strongly allowed states are shown above or below the horizontal band representing the transition energy. The calculations for 2a were carried out for two geometries of the phenyl ring: orthogonal (Φ = 90°) and parallel (Φ = 0°) to the boron-dipyrrin plane, for which the symmetry labels are approximate. The calculation for 2a-Bu2 was carried out for an orthogonal phenyl group (Φ = 90°). Other details are as in Figure 6. Note that a2 states are symmetry forbidden (f = 0.0) and that all of the low-lying b1 states are very weak (f < 0.01).

We conclude that the strong absorption band at 30kK (∼330 nm) is due mainly to the 2A1transition and that the less intense 2B2 transition is associated with the smaller band observed at 26kK (∼380 nm). Spectral fitting indicates that the lower of these two bands has an oscillator strength roughly half that of the higher energy feature, in reasonable agreement with the calculated SACCI-CISD oscillator strengths for the 2A1 (fcalc = 0.37) and 2B2 (fcalc = 0.18) states. [For reference, the strongly allowed lowest energy B2 state has a calculated oscillator strength of 0.44.] This assessment of the contribution of the 2A1 state, along with 1A1 and 2B2 states, to the absorption in the 300-400 nm region is consistent with several observations. First, the absorption contour in this region for a given solvent is dependent on the nature (or presence) of the 5-aryl ring (Figures 2A-E). Since different dihedral angles are expected for the different types of complexes (e.g., hindered versus unhindered) on the basis of the ground-state structural studies (Table 1 and Figure 1), the contribution of the 2A1 to absorption in the 300-400 nm region will differ. Second, the calculations indicate that the 2A1 state has a somewhat larger dipole moment than the ground state (the B2 states have a slightly smaller dipole moment than the ground state). Thus, an increase in solvent polarity will tend to cause the aryl ring to rotate to enhance the excited-state dipole moment and thereby increase solvent stabilization. According to the calculations, this will also increase the oscillator strength and contribution of the 2A1 state to the near-UV absorption contour. These predictions are consistent with the solvent polarity effects on the absorption spectra (Figure 2E and Supporting Information). Third, calculations indicate that the A1 transitions are polarized perpendicular to the B2 transitions (see Table 2 described below).Thus, a contribution of the 2A2 (and weaker 1A2) transition to the absorption contour in the 300-400 nm region (and not simply just the 2B2 transition) is consistent with the finding that the polarization in this region tends toward perpendicularity to the S0↔S1(1B2) absorption and fluorescence bands.

In summary, the calculations and experimental results are consistent with a lowest lying B2 state for all the compounds investigated, and the fact that the lowest three excited singlet states are A1 or B2 symmetry. Interestingly, the separation between the lowest and the second excited singlet states is relatively large, regardless of substitution or aryl geometry.

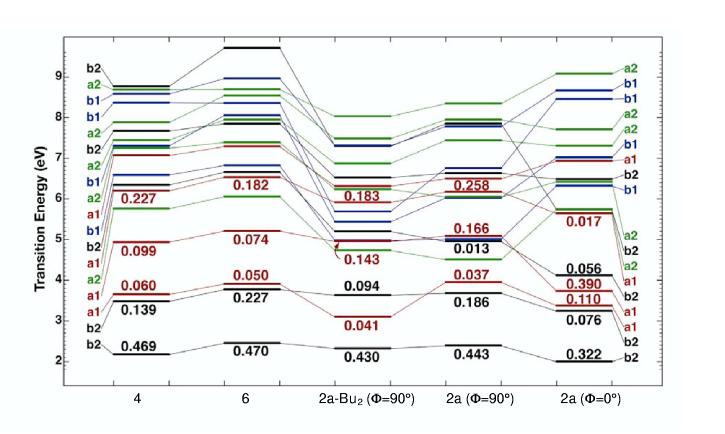

Configurational Characteristics of the Lowest Excited Singlet States.The configurational properties of the lowest-lying B2 excited singlet state in the phenyl-substituted dye 2a are presented in Figure 8, on the basis of SACCI calculations using full single and double CI. Note that while Figures 6 and 7 display calculated excited-state transition energies using vertical bars (Figure 6) or horizontal lines (Figure 7), the horizontal lines in Figure 8 show the Hartree-Fock energies of the molecular orbitals. The symmetry of the closed-shell ground state of a molecule with C2v symmetry is A1, and the π molecular orbitals of the boron-dipyrrin framework have a2 or b1 symmetry. For all the molecules investigated here, the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) has b1 symmetry and is notably isolated in energy from the other unoccupied orbitals (Figure 8). Thus, the dominant configuration for most of the lowlying excited states involves excitation from one of the filled orbitals into the b1 LUMO. The situation is illustrated in Table 3, which provides a symmetry analysis of the transition polarization (x and y are in plane) and the lowest energy configurations on the basis of the boron-dipyrrin orbitals. (The A2 state is rigorously forbidden.) Since the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) has a2 symmetry, inspection of Table 3, along with the orbital energies in Figure 8 provides a clear picture of why the lowest singlet state is an allowed B2 state and why this state is well separated in energy from the second excited singlet state.

Figure 8.

The primary configurational properties of the lowest-lying B2 singlet states of 2a for two geometries of the phenyl ring: orthogonal to the boron-dipyrrin plane (Φ = 90°, left) and parallel to the dipyrrin plane (Φ = 0°, right). The lowest excited singlet state is highly ionic in character and is well described as a simple HOMO (a2) → LUMO (b1) one-electron excitation. The nature of the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO, a2 or a2-like symmetry) is relatively invariant in both character and energy to phenyl rotation. In contrast, the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO, b1 or b1-like symmetry) extends into the phenyl group upon rotation and is highly stabilized by the increased extent of the pi-electron system when the phenyl group is parallel to the boron-dipyrrin plane (Φ = 0°). Stabilization of the LUMO is the dominant electronic driving force for phenyl group relaxation towards planarity in the S1 excited singlet state.

Table 3.

Dominant configurations of boron-dipyrrin states.

| State | Transition Polarization | Configurations |

|---|---|---|

| A1 | z | b1←b1 |

| A2 | forbidden | b1←b2 |

| B1 | x | b1←a1; a2←b2 |

| B2 | y | b1←a2 |

We now explore the nature of the lowest B2 excited singlet state in 2a in more detail. The calculation at the lower left of Figure 8 shows the composition of the transition with the 5-phenyl group rotated orthogonal to the plane of the boron-dipyrrin framework, while the calculation at lower right shows the transition with the phenyl group rotated into the dipyrrin plane. The symmetry labels for the latter case are approximate. Single arrows represent single excitations and double arrows represent double excitations, with the percentage contribution for each excitation shown within the yellow circles. The sum of the percentages is shown to the right of the set, and in both cases, more than 90% of the state configurational character is represented by the seven configurations. More interestingly, the rotation of the phenyl group has only minor impact on the configurational distribution, and the lowest B2 singlet state is described well as a simple HOMO to LUMO transition. As shown in the top two rows of panels in Figure 8, the HOMO is localized in the boron-dipyrrin framework irrespective of phenyl-group geometry. In contrast, the LUMO is localized in the boron-dipyrrin framework when the phenyl group is orthogonal, but this orbital is extensively delocalized into the phenyl ring upon rotation of the latter into the plane of the dipyrrin system. This delocalization of electron density is responsible for the decrease in the LUMO energy and the corresponding decrease in the transition energy upon aryl ring rotation (Figure 7). As is shown in Figure 8, the LUMO is the single most important orbital in defining the configurational characteristics of the lowest-lying, strongly allowed B2 state because the LUMO participates in over 90% of the configurational description.

The same strongly allowed B2 character of the lowest excited state is found when the fluorine atoms of 2a are replaced by ethyl groups, which were substituted for n-butyl groups of 2a-Bu2 to make the calculation more efficient. As is shown in Figure 7 and described in the Supporting Information, the calculations also indicate that the alkyl groups should preferentially stabilize the A1 states, thereby reversing the ordering of the second and third excited states (1A1 with 2B1), with consequences on the absorption contour between 300 and 400 nm (see Figure 2). The calculations showed no differences in the potential energy surfaces for the ground or lowest excited state compared to 2a.

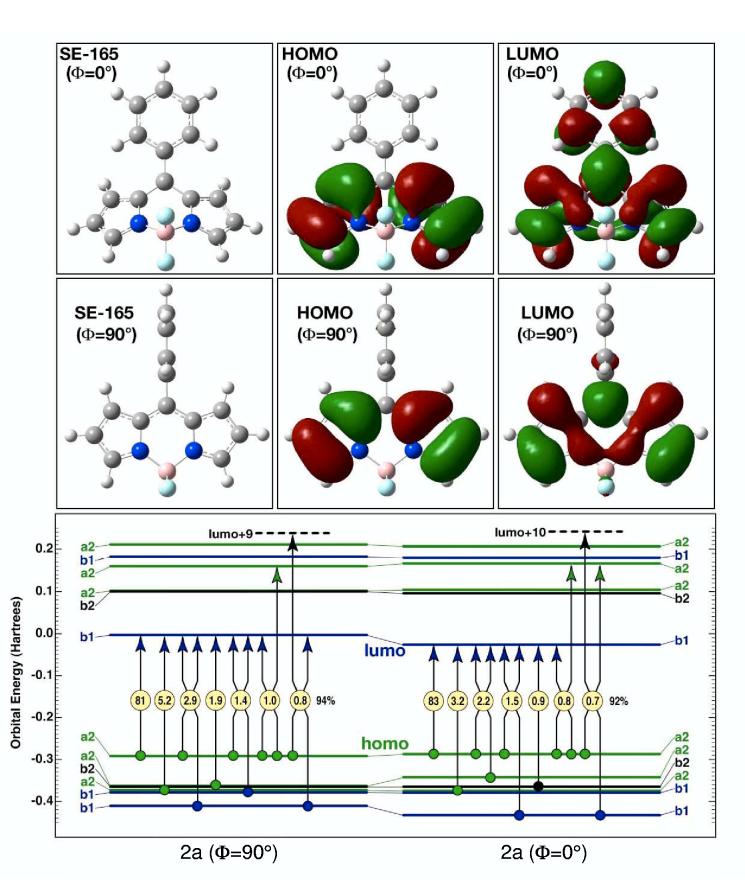

Franck-Condon Activity in the Optical Spectra. The strongly allowed low-energy absorption bands in these compounds are unusually sharp, exhibiting full-widths at half-maxima of less than 1200 cm-1 (Figures 2 and 6). This sharpness is observed regardless of the substituents at the 5-position or on the pyrrole rings. Comparisons of the calculated ground- and excited-state geometries provide a perspective on this observation. Simply stated, the ground-and lowest-excited B2 states have virtually identical geometries in the Franck-Condon region. To a first approximation, only A1 or A1-like vibrational modes are Franck-Condon active and these modes are confined largely to the ring system. The promoting modes in absorption and fluorescence of 4 involve in-plane breathing vibrations of the ring atoms coupled to a N–B–N angular mode (see illustrations in Supporting Information). These modes are relatively insensitive to whether there is hydrogen or an aryl ring at the 5-position. The possible exceptions to this rule involve the phenyl and 4-tert-butylphenyl complexes 2a and 2b, respectively, which have no internal hindrance to aryl rotation. As described below, 2a (and by comparison 2b) has a lowest excited singlet state geometry that is significantly different than the ground-state geometry (Figures 9A and B). Nevertheless, this significant change in geometry generates only a minor increase in the optical bandwidths (Figure 6). There are two reasons for this observation. First, the LUMO does not expand into the aryl group significantly until the ring approaches within 30° of the planar geometry, an orientation that is never explored in the ground state at ambient temperature because the LUMO is populated only in the excited state. Thus, the relaxed excited-state geometry is outside of the Franck-Condon active region. Second, the vibration that is responsible for dihedral relaxation of the phenyl group is a low-frequency torsional mode that has poor vibrational overlap with the ground-state modes regardless of geometry. The result is a Franck-Condon distribution that is dominated by in-plane A1-like modes of the dipyrrin framework in all of the compounds investigated here. This observation provides insight into the fluorescence quantum yields in those compounds (2d, 2c) wherein aryl rotation is restricted (Table 2).

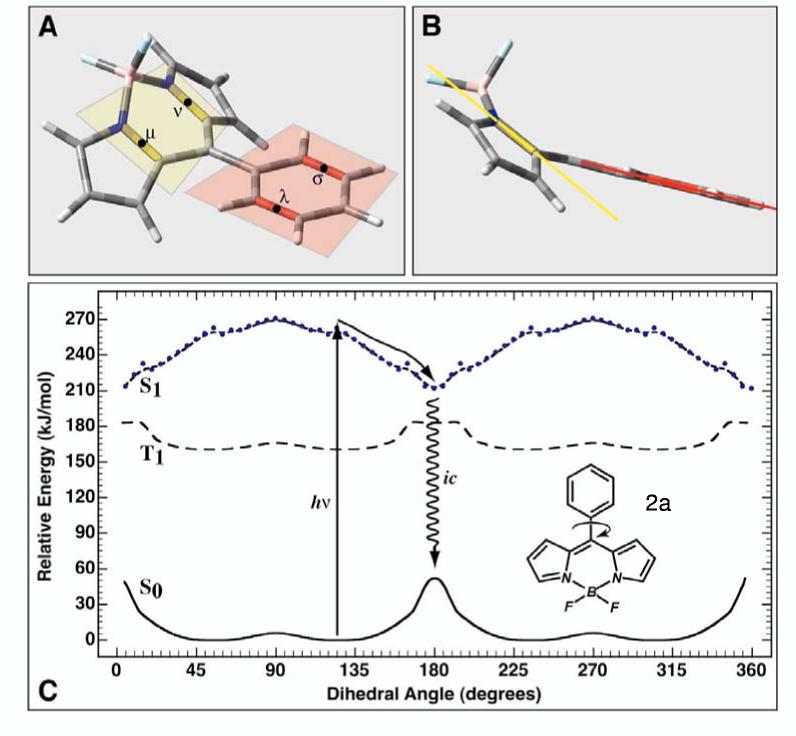

Figure 9.

The ground, first excited triplet state and first excited singlet state potential energy surfaces of 2a as a function of phenyl group rotation is shown in C. As the phenyl group rotates into the plane of the boron-dipyrrin framework, repulsions between the hydrogen atoms on both groups force a puckering as shown in A and B. This distortion requires that we define the angle of rotation with reference to the rotation of the yellow and red planes. In practice, the dihedral angle is calculated in terms of the bond centroids υ, ν, λ and σ as shown in insert A. The alignment shown in B represents a dihedral angle of 0° (which because of symmetry is identical to 180° or 360°). The ground and triplet state surfaces were calculated using B3LYP/6-31G(d) methods. The excited singlet state surface was calculated using full single CI minimization with a correlative correction calculated by using SACCI doubles (see text).

Ground and Excited State Potential Energy Surfaces. Rotation of the phenyl or aryl ring relative to the boron-dipyrrin plane is the key conformational degree of freedom that determines the photophysical properties of these molecules. However, as the aryl group rotates, interactions between the o-aryl groups and the hydrogen atoms of the dipyrrin framework forces the latter to pucker, as shown in Figures 9A and B. In order to describe the rotation of the aryl group with internal consistency, we use two bond centroids on the boron-dipyrrin ring (μ and ν>, Figure 9A) and two bond centroids on the aryl group (λ and σ) to define the dihedral angle. The potential-energy surfaces for rotation of the phenyl (2a, Figure 9C), mesityl (2d, Figure 10) and o-tolyl (2c, Supporting Information) groups are plotted with reference to this torsional angle. Furthermore, only the lowest energy conformation as a function of this angle is plotted. Computationally, there is a tendency of the ring to pucker in an asymmetric fashion as the aryl group approaches coplanarity with the dipyrrin framework. The asymmetry depends upon the initial conformation and is an artificial component of the minimization process. In reality, an ambient temperature system will explore many different conformations during the aryl rotation so our decision to plot only the lowest-energy conformation is appropriate.

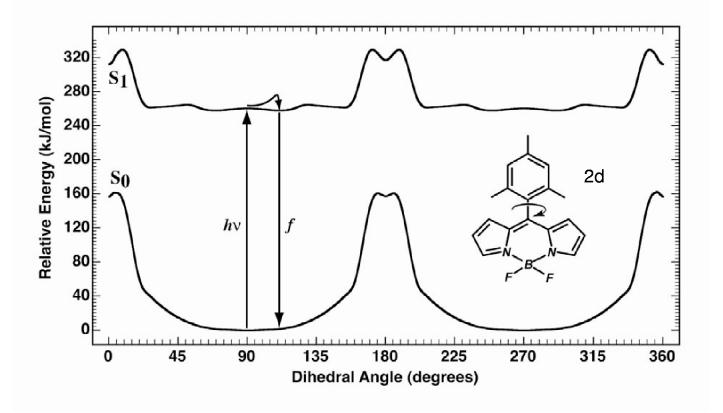

Figure 10.

The ground and first excited singlet state potential energy surfaces of 2d as a function of mesityl group rotation. Details are as in Figure 9.

Excited-state Dynamics for 2a. The most interesting potential energy surfaces are calculated for 2a and are shown in Figure 9C. This molecule is calculated to have a barrier to phenyl rotation in the ground state of approximately 50 kJ/mol; the lowest energy conformation is one in which the phenyl group is twisted to have an angle of about 55° (145°), namely 35° from perpendicularity. This result is in good agreement with the average dihedral angle of ∼60° determined from the X-ray structure (Table 1). The phenyl group in the lowest excited triplet state has a barrier to rotation of 25 kJ/mol, roughly half that observed in the ground state, and displays a local minimum in the planar geometry (Figure 9). In contrast, the lowest excited singlet state displays a potential surface dramatically different, with a minimum geometry at a dihedral angle of 180° (Figures 9A and B). The origin of this potential-surface minimum is intimately associated with the delocalization of the LUMO as discussed above and as shown in Figure 8. We have discussed the basic driving forces behind this phenomenon in a previous paper.11 However, our previous theoretical treatment used semi-empirical methods with limited double CI to explore the excited-state surface. The higher level theory used in this study provides a higher correlated singlet excited-state surface, and reveals that the S1 surface provides virtually no barrier to rotation of the phenyl group towards planarity in 2a (compare Figure 9 with Figures 7 and 8 of Ref 11). The new calculations provide a clear perspective on why 2a (and 2b) has a negligible fluorescence quantum yield. The barrier-less or nearly barrier-less S1 surface provides a rapid transfer of the excited-state population to the delocalized puckered conformation. In this form, the phenyl group has rotated to a dihedral angle of 180°, where there is a new minimum in the excited-state surface accompanied by enhanced electron delocalization. The S1 excited state in this conformation has efficient coupling to the ground state via nonradiative processes. If any emission were to occur, it would be in the infrared.

We note with interest that the triplet excited state does not share a minimum energy delocalized puckered conformation. The factors underlying this observation are described in the Supporting Information. The time-resolved absorption data described above indicate that internal conversion of the lowest excited singlet state is so facile as to circumvent any appreciable intersystem crossing to produce the triplet excited state.

Excited-state Dynamics for 2d. The ground and first excited singlet state surfaces for 2d are shown in Figure 10. The o- and o′-methyl groups cause increased repulsion between the mesityl group and the boron-dipyrrin framework to such an extent that the lowest-energy ground state conformation is one in which the mesityl ring lies essentially orthogonal to the dipyrrin framework. As one might anticipate, the delocalized puckered state in which the mesityl ring rotates approximately coplanar with the dipyrrin is not the lowest energy excited singlet state conformation (as it was for 2a), but lies 60 kJ/mol higher in energy than the orthogonal or nearly orthogonal conformations. We conclude that excitation into the excited singlet manifold of 2d generates only a modest change in the mesityl group orientation, and that fluorescence from the relaxed S1 state should be efficient. This prediction is in excellent agreement with the findings from static and time-resolved optical spectroscopy.

Excited-state Dynamics for 2c. The ground and first excited singlet state surfaces for 2c are shown in the Supporting Information. The 2c surface is qualitatively identical to that observed for 2d but has some interesting features in terms of local minima that are unlikely to have an observable impact on the excited-state dynamics. These conclusions are in keeping with the finding that the photophysical behavior of o-tolyl-substituted 2c is virtually identical to that of 2d. Thus, the presence of only one o-methyl group on the aryl ring provides sufficient hindrance to internal rotation to afford the substantial change in excited-state dynamics and emission properties compared to the unhindered analogues.

Conclusions

A family of 5-aryl-substituted boron-dipyrrin dyes has been synthesized and then characterized by X-ray diffraction, photophysical studies, and theory. The results demonstrate the dominant role of aryl rotation in governing the excited-state dynamics and fluorescence properties of these dyes. The results should facilitate the further use of this class of dyes and related systems as optical probes in the life sciences and other applications.

Experimental Section

Synthesis

General. 1H NMR spectra (400 MHz) and 13C NMR spectra (100 MHz) were collected in CDCl3 unless noted otherwise. Absorption spectra and fluorescence spectra (and yields) were collected in toluene at room temperature unless noted otherwise. Adsorption column chromatography was performed using flash silica gel. Silica gel (40 μm average particle size) was used for column chromatography. Anhydrous CH2Cl2 was purchased from Aldrich. All other chemicals were reagent grade and were used as received. Compounds 4 (BDPY 3921) and 5 (BDPY 3922) were purchased from Molecular Probes Inc.

Noncommercial compounds. Compounds 5-(o-tolyl)dipyrromethane (7c),4 5-phenyldipyrrin (8a),6,12 5-(4-tert-butylphenyl)dipyrrin (8b),12 and 5-mesityldipyrrin (8d)12 were prepared according to literature procedures.

N,N′-difluoroboryl-5-phenyldipyrrin (2a). A solution of 8a (440 mg, 2.00 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (20 mL) was treated with TEA (2.79 mL, 20.0 mmol, 10 equiv) and BF3·O(Et)2 (2.53 mL, 20.0 mmol, 10 equiv) at room temperature. After 30 min, TLC analysis (silica, CH2Cl2) indicated complete consumption of the starting material. The reaction mixture was washed with saturated aqueous NaHCO3 (100 mL x 3). The organic layer was dried (Na2SO4), concentrated, and chromatographed [silica, CH2Cl2/hexanes (1:1)], affording a brown oil. Addition of CH2Cl2/hexanes precipitated a red-orange solid (105 mg, 19%): mp 99–100 °C; 1H NMR Δ 6.55 (d, J = 3.6 Hz, 2H), 6.94 (d, J = 3.6 Hz, 2H), 7.51–7.60 (m, 5H), 7.93–7.97 (m, 2H); 13C NMR Δ 128.4, 130.44, 130.74, 131.6, 133.7, 134.9, 144.0, 147.3; FABMS obsd 268.0974, calcd 268.0983 (C15H11BF2N2); Anal. Calcd: C, 67.21; H, 4.14; N, 10.45. Found: C, 67.28; H, 4.29; N, 10.32; λabs 504 nm, λem 521 nm, Φf = 0.062.

N,N′-difluoroboryl-5-(4-tert-butylphenyl)dipyrrin (2b). Following the procedure for 2a, the reaction of 8b (1.10 g, 4.00 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (40 mL) with TEA (5.58 mL, 40.0 mmol, 10 equiv) and BF3·O(Et)2 (5.07 mL, 40.0 mmol, 10 equiv) followed by workup and chromatography [silica, CH2Cl2/hexanes (1:1)] afforded an orange solid. The solid was suspended in methanol and sonicated. The suspension was filtered, affording a red-orange solid (0.625 g, 50%): mp 169–170 °C; 1H NMR Δ 1.40 (s, 9H), 6.52–6.57 (m, 2H), 7.00 (d, J = 3.6 Hz, 2H), 7.52 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.54 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.91–7.95 (m, 2H); 13C NMR Δ 31.1, 34.9, 118.2, 125.4, 130.44, 130.85, 131.6, 134.8, 143.5, 147.6, 154.4; FABMS obsd 324.1620, calcd 324.1609 (C19H19BF2N2); Anal. Calcd: C, 70.39; H, 5.91; N, 8.64. Found: C, 70.39; H, 5.87; N, 8.59; λabs 502 nm, λem 522 nm, Φf = 0.069.

N,N′-difluoroboryl-5-o-tolyldipyrrin (2c). Following the procedure for 2a, the reaction of 8c (0.214 g, 0.912 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (10 mL) with TEA (1.27 mL, 0.914 mmol, 10 equiv) and BF3·O(Et)2 (1.16 mL, 0.915 mmol, 10 equiv) followed by workup, chromatography [silica, CH2Cl2/hexanes (1:1)], and recrystallization (methanol/water) afforded an orange solid (0.175 g, 68%): mp 135 °C; 1H NMR Δ 2.25 (s, 3H), 6.50 (d, J = 3.6 Hz, 2H), 6.72 (d, J = 3.6 Hz, 2H), 7.27–7.31 (m, 2H), 7.34 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.41–7.45 (m, 1H), 7.92–7.95 (m, 2H); 13C NMR Δ 20.1, 118.6, 125.3, 129.7, 129.8, 130.4, 131.0, 136.3, 144.4; FABMS obsd 282.1146, calcd 282.1140 (C16H13BF2N2); Anal. Calcd: C, 68.12; H, 4.64; N, 9.93. Found: C, 67.95; H, 4.79; N, 9.73; λabs 503 nm, λem 518 nm, Φf = 0.93.

N,N′-difluoroboryl-5-mesityldipyrrin (2d). Following the procedure for 2a, the reaction of 8d (1.05 g, 4.00 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (40 mL) with TEA (5.58 mL, 40.0 mmol, 10 equiv) and BF3·O(Et)2 (5.07 mL, 40.0 mmol, 10 equiv) followed by workup and chromatography [silica, CH2Cl2hexanes (1:1)] afforded an orange solid. The solid was suspended in methanol and sonicated. The suspension was filtered, affording a red-orange solid (0.677 g, 52%): mp 168–169 °C; 1H NMR Δ 2.10 (s, 6H), 2.37 (s, 3H), 6.47 (d, J = 4.0 Hz, 2H), 6.68 (d, J = 4.0 Hz, 2H), 6.96 (s, 2H), 7.90–7.94 (m, 2H); 13C NMR Δ 19.9, 21.1, 118.5, 128.1, 129.6, 130.1, 135.3, 136.2, 138.8, 144.2, 147.6; FABMS obsd 310.1447, calcd 310.1453 (C18H17BF2N2); Anal. Calcd: C, 69.71; H, 5.52; N, 9.03. Found: C, 69.50; H, 5.60; N, 8.90; λabs 503 nm, λem 517 nm, Φf = 0.93.

N,N′-(Dimethylboryl)-5-phenyldipyrrin (2a-Me2). A 20-mL reaction vial was charged with 8a (72 mg, 0.32 mmol), anhydrous CH2Cl2 (3.6 mL), TEA (89 μL, 0.64 mmol) and a magnetic stirring bar. The vessel was capped with a septum and bromodimethylborane (63 μL, 0.64 mmol) was added via syringe. The reaction mixture was stirred for 90 min. The reaction mixture was then concentrated to dryness. The residue was dissolved in a minimum of CHCl3 and chromatographed (silica, CHCl3). The product eluted as an orange band. Fractions containing the pure product were concentrated, providing an orange solid (77 mg, 89%): mp 124-125 °C; 1H NMR Δ 0.20 (s, 6H), 6.49–6.53 (m, 2H), 6.83–6.87 (m, 2H), 7.47–7.63 (m, 5H), 7.67–7.71 (m, 2H); 13C NMR Δ 14.5 (brs), 117.5, 127.96, 128.3, 130.1, 130.6, 133.4, 135.2, 142.8, 146.5; LDMS obsd 259.6, calcd 260.2 (C17H17BN2); λabs 495 nm, λem 518 nm, Φf = 0.008.

N,N′-(Dibutylboryl)-5-phenyldipyrrin (2a-Bu2). Following the procedure for 2a-Me2, the reaction of 8a (75 mg, 0.34 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (1.0 mL) with TEA (95 μL, 0.68 mmol) and dibutylboron triflate (680 μL of a 1.0 M solution in CH2Cl2, 0.68 mmol) was carried out for 4 h, whereupon TLC analysis (silica, hexanes) indicated that the reaction was complete. The mixture was diluted with 4 mL of hexanes and chromatographed (silica, hexanes w/2% ethyl acetate). The product eluted as a yellow band. Fractions containing the pure product were concentrated, providing a sticky orange resin (30.0 mg, 26%). 1H NMR analysis indicated the presence of a small impurity (∼5%). Additional silica gel chromatography, even in neat hexanes or pentane could not remove this species. 1H NMR Δ 0.58–0.85 (m, 10H), 0.91–1.15 (m, 2H), 1.50–1.80 (m, 3H), 1.53–1.70 (m, 1H), 2.80–2.98 (m, 2H), 6.45 (d, J = 4.4 Hz, 0.5H), 6.46–6.49 (m, 0.5H),6.52–6.58 (m, 1H), 6.65–6.67 (m, 0.5H), 6.82–6.86 (m, 1.5H), 7.43–7.57 (m, 5H), 7.58–7.63 (m, 2H); LDMS obsd 343.0, calcd 344.2 (C23H29BN2); λabs 498 nm, λem 521 nm, Φf = 0.008. The relative complexity of the 1H NMR signature obtained is not reflective of the C2v symmetry expected for this compound; however, such complexity is not a consequence of the tiny amount of impurity.

N,N′-(Dimethylboryl)-5-mesityldipyrrin (2d-Me2). Following the procedure for 2a-Me2, the reaction of 8d (50.0 mg, 0.191 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (2.0 mL) with TEA (265 μL, 1.91 mmol) and bromodimethylborane (186 μL, 1.91 mmol) was carried out for 30 min. Workup and chromatography [silica, hexanes/CH2Cl2 (5:1)] afforded a sticky oil that solidified to an orange solid (50 mg, 87%): mp 113 °C; 1H NMR Δ 0.19 (s, 6H), 2.11 (s, 6H), 2.38 (s, 3H), 6.43 (dd, J = 4.0 Hz, J = 2.0 Hz, 2H), 6.60 (dd, J = 4.4 Hz, J = 0.8 Hz, 2H), 6.96 (s, 2H), 7.63–7.68 (m, 2H);13C NMR Δ 13.7 (brs), 19.8, 21.1, 117.1, 126.3, 127.9, 131.1, 133.5, 136.3, 138.1, 142.2, 146.2;

FABMS obsd 303.2037, calcd 303.2033 [(M + H)+; M = C20H23BN2]; λabs 497 nm, λem 514 nm, Φf = 0.40.

N,N′-(Dibutylboryl)-5-mesityldipyrrin (2d-Bu2). Following the procedure for 2a-Me2, the reaction of 8d (60 mg, 0.23 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (3.0 mL) with TEA (32 μL, 0.23 mmol) and dibutylboron triflate (460 μL of a 1.0 M solution in CH2Cl2, 0.46 mmol) was carried out for 1 h, whereupon TLC analysis (silica, hexanes) indicated that the reaction was complete. The mixture was diluted with 3 mL of hexanes and chromatographed over a short silica column in hexanes. The product eluted as a yellow band. Fractions containing the product were concentrated and chromatographed over a second column in order to remove a pink impurity that followed closely behind the desired product. Fractions containing the pure product were concentrated, providing a sticky orange resin (17 mg, 19%): 1H NMR Δ 0.67–0.81 (m, 14H), 1.06–1.13 (m, 4H), 2.07 (s, 6H), 2.37 (s, 3H), 6.46–6.47 (m, 2H), 6.57–6.58 (m, 2H), 6.95 (s, 2H), 7.55–7.60 (m, 2H); 13C NMR Δ 14.6, 20.1, 21.5, 26.4, 28.1, 30.1, 117.3, 125.8, 128.1, 131.3, 134.5, 136.4, 138.2, 142.0, 146.5; LDMS obsd 386.2, calcd 386.3 (C26H35BN2); Anal. Calcd for C26H35BN2: C, 80.82; H, 9.13; N, 7.25; Found: C, 80.24; H, 9.41; N, 6.88; λabs 496 nm, λem 514 nm, Φf = 0.034.

N,N′-(9-Borabicyclo[3.3.1]-non-9-yl)-5-mesityldipyrrin (2d-BN). Following the procedure for 2a-Me2, the reaction of 8d (61 mg, 0.23 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (3.0 mL) with TEA (32 μL, 0.23 mmol) and 9-BBN triflate (460 μL of a 0.5 M solution in CH2Cl2, 0.46 mmol) was carried out for 1 h, whereupon TLC analysis (silica, hexanes) indicated that the reaction was complete. The mixture was diluted with 3 mL of hexanes and chromatographed [silica, hexanes/CH2Cl2 (2:1)], providing an orange solid (45 mg, 51%): mp 117–118 °C; 1H NMR Δ 0.79–0.85 (m, 2H), 1.67–1.79 (m, 6H), 2.04–2.25 (m, 6H), 2.08 (s, 6H), 2.38 (s, 3H), 6.39–6.42 (m, 2H), 6.61–6.66 (m, 2H), 6.96 (s, 2H), 8.29–8.32 (m, 2H); 13C NMR Δ 20.1, 21.4, 23.2, 25.54 (brs), 31.3, 116.1, 127.4, 128.1, 131.7, 135.7, 136.7, 138.2, 144.9, 146.3; LDMS obsd 381.2, calcd 382.3; FABMS obsd 382.2598, calcd 382.2580 (C26H31BN2); λabs 495 nm, λem 518 nm, Φf = 0.004.

5-(o-Tolyl)dipyrrin (8c). Following a general procedure,12 a solution of 7c (2.50 g, 10.6 mmol) in THF (50 mL) was treated dropwise with a solution of DDQ (2.41 g, 10.6 mmol) in THF (25 mL) at room temperature. After stirring for 1 h, TLC analysis showed incomplete oxidation. Therefore, a solution of DDQ (0.482 g, 2.12 mmol) in THF (2 mL) was added and the reaction mixture was stirred for another 20 min. The solvent was removed and the resulting crude was chromatographed [silica, CH2Cl2/MeOH (98:2)], affording a brown-yellowish solid (2.09 g, 84%): mp 79–80 °C; 1H NMR Δ 2.19 (s, 3H), 6.42 (dd, J = 4.4 Hz, J = 1.6 Hz, 2H), 6.49–6.51 (m, 2H), 7.26–7.30 (m, 3H), 7.36–7.42 (m, 2H), 7.80–7.84 (m, 2H); 13C NMR Δ 19.8, 117.4, 124.9, 128.8, 129.9, 130.2, 131.2, 136.7, 144.1, 154.4; LDMS obsd 234.8; calcd 234.3; FABMS obsd 235.1234, calcd 235.1235 [(M + H)+; M = C16H14N2]; λabs 432 nm.

Photophysical Characterization.

Static Absorption and Emission Spectroscopy. Static absorption (Cary 100) and fluorescence (Spex Tau2) measurements were performed as described previously.18For emission studies, non-deaerated samples with an absorbance ≤0.15 (typically 0.3-0.8 μM) at λexc were employed. Emission quantum yields were measured relative to fluorescein in 0.1 M NaOH (Φf = 0.92)19>and were corrected for solvent refractive index.

Time-Resolved Fluorescence Spectroscopy. Fluorescence lifetimes were obtained on samples that had concentrations of 0.5-10 μM and were deaerated by bubbling with N2. Lifetimes were determined by the fluorescence modulation (phase shift) technique using a Spex Tau2 spectrofluorometer. Samples were excited at various wavelengths and detected through appropriate colored glass filters. Modulation frequencies from 20–300 MHz were utilized and both the fluorescence phase shift and modulation amplitude were analyzed.

Time-Resolved Absorption Spectroscopy. Transient absorption data were acquired as described previously.18 Samples (∼10 μM) in 2 mm pathlength cuvettes at room temperature were excited at 10 Hz with ∼130 fs, 5-30 μJ pulses at the appropriate wavelength and probed with white-light probe pulses of comparable duration. Spectra shown at <1 ps were constructed from spectra at closely spaced time intervals to account for the time-dispersion of wavelengths in the white-light probe pulse. Kinetic data were fit to functions consisting of one to three exponentials (convoluted with an instrument response) plus a constant asymptote.

Theory

Ground-state potential energy surfaces were generated by scanning the aryl dihedral angle and optimizing the remaining degrees of freedom using density functional methods and redundant internal coordinates. We selected the B3LYP hybrid functional of Becke, Lee, Yang, and Parr20,21 and used a 6-31G(d) basis set. This combination provides a near optimum combination of accuracy and computational efficiency.22 The lowest excited triplet state surfaces were generated by using the identical procedures, and the triplet state geometry was then used as the guess geometry for the excited singlet state optimizations. The lowest singlet state geometries were calculated by using gradients generated within full single excitation configuration interaction with inner shell orbitals (e.g., carbon 1s) frozen. The resulting energies were then adjusted for correlation by using double CI as provided by a windowed [32(filled)+32(open)] symmetry-adapted cluster configuration interaction (SACCI) calculation.23The Opt(CIS)+ΔE(CID/SACCI) approximation can be justified on the basis of two observations. First, as we will demonstrate later, the lowest singlet state is an ionic state dominated by singly excited configurations (>80%). Second, test calculations using SACCI with single and double CI indicate that single CI optimization generates a geometry that is within a few percent of that generated using single and double CI in terms of redundant internal coordinates when the aryl group dihedral angle is fixed. Nevertheless, double CI plays an important role in the energy correlation of the excited singlet state when the aryl ring approaches planarity with respect to the boron-dipyrrin framework.

Excited-state spectroscopic properties were calculated by using MNDO-PSDCI24,25 and SACCI23 methods with partial single and double CI assuming vacuum conditions. Test calculations using full CISD on high symmetry molecules indicated that the states calculated using restricted basis set had converged to within 0.1 eV of the full CISD values. The MNDOPSDCI and SACCI methods generate comparable energies and properties for the lowest four excited singlet states, but these methods diverge for the higher energy transitions. We report here only the results for the SACCI calculations, which we consider to be more accurate and reliable. The SACCI calculations used the Huzinaga-Dunning D95 double zeta basis set, which has been shown to be optimal for spectroscopic calculations.23

The ab-initio and density functional calculations were carried out using Gaussian-03 Linux Revision B0526 with Linda as the parallel resource software running under Red Hat Linux 9.0 (Red Hat, Inc., Raleigh, NC). The hardware environment was a 16-node (32 processors) Beowulf cluster manufactured by Western Scientific (San Diego, CA). Each node is composed of two 1266 MHz Intel Pentium III processors, 1 GB of DDR RAM, and a single 34 GB SEAGATE hard drive for local data buffering. The nodes are networked using fast Ethernet (Ethernet Pro 100). The semiempirical MNDO-PSDCI and Gaussian-03 survey calculations were run on a dual processor 1250 MHz Macintosh G5.

Supplementary Material

scheme 3

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by grants from the Department of Energy (JSL, DFB, and DH) and the National Institutes of Health (GM-38401 to W.R.S). Mass spectra were obtained at the Mass Spectrometry Laboratory for Biotechnology at North Carolina State University. Partial funding for the NCSU Facility was obtained from the North Carolina Biotechnology Center and the NSF.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Theoretical analysis of the excited-state surfaces and Franck-Condon-active modes for selected compounds, static absorption and emission spectra, time-resolved absorption and emission spectra, and ORTEP diagrams of the structures. Crystallographic data is available as CIF files. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- (1).Treibs A, Kreuzer F-H. Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1968;718:208–223. doi: 10.1002/jlac.19687180118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).(a) Kim H, Burghart A, Welch MB, Reibenspies J, Burgess K. Chem. Commun. 1999:1889–1890. [Google Scholar]; (b) Burghart A, Kim H, Welch MB, Thoresen LH, Reibenspies J, Burgess K. J. Org. Chem. 1999;64:7813–7819. [Google Scholar]; (c) Chen J, Burghart A, Derecskei-Kovacs A, Burgess K. J. Org. Chem. 2000;65:2900–2906. doi: 10.1021/jo991927o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Burghart A, Thoresen LH, Chen J, Burgess K, Bergström F, Johansson LB-Å. Chem. Commun. 2000:2203–2204. [Google Scholar]

- (3).Lee C-H, Lindsey JS. Tetrahedron. 1994;50:11427–11440. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2008.08.096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Littler BJ, Miller MA, Hung C-H, Wagner RW, O'Shea DF, Boyle PD, Lindsey JS. J. Org. Chem. 1999;64:1391–1396. [Google Scholar]

- (5).Laha JK, Dhanalekshmi S, Taniguchi M, Ambroise A, Lindsey JS. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2003;7:799–812. [Google Scholar]

- (6).Brückner C, Karunaratne V, Rettig SJ, Dolphin D. Can. J. Chem. 1996;74:2182–2193. [Google Scholar]

- (7).Wagner RW, Lindsey JS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:9759–9760. [Google Scholar]

- (8).(a) Wagner RW, Lindsey JS. Pure Appl. Chem. 1996;68:1373–1380. [Google Scholar]; (b) Wagner RW, Lindsey JS. Pure Appl. Chem. 1998;70(8):i. [Google Scholar]

- (9).Ambroise A, Kirmaier C, Wagner RW, Loewe RS, Bocian DF, Holten D, Lindsey JS. J. Org. Chem. 2002;67:3811–3826. doi: 10.1021/jo025561i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).(a) Wagner RW, Lindsey JS, Seth J, Palaniappan V, Bocian DF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:3996–3997. [Google Scholar]; (b) Ambroise A, Wagner RW, Rao PD, Riggs JA, Hascoat P, Diers JR, Seth J, Lammi RK, Bocian DF, Holten D, Lindsey JS. Chem. Mater. 2001;13:1023–1034. [Google Scholar]

- (11).Li F, Yang SI, Ciringh Y, Seth J, Martin CH, III, Singh DL, Kim D, Birge RR, Bocian DF, Holten D, Lindsey JS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:10001–10017. [Google Scholar]

- (12).Yu L, Muthukumaran K, Sazanovich IV, Kirmaier C, Hindin E, Diers JR, Boyle PD, Bocian DF, Holten D, Lindsey JS. Inorg. Chem. 2003;42:6629–6647. doi: 10.1021/ic034559m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Sazanovich IV, Kirmaier C, Hindin E, Yu L, Bocian DF, Lindsey JS, Holten D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:2664–2665. doi: 10.1021/ja038763k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Jones G, Kumar S, Klueva O, Pacheco D. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2003;107:8429–8434. [Google Scholar]

- (15).Arbeloa FL, Arbeloa TL, Arbeloa IL. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A. 1999;121:177–182. [Google Scholar]

- (16).Karolin J, Johansson LB-A, Strandberg L, Ny T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:7801–7806. [Google Scholar]

- (17).Johnson ID, Kang HC, Haugland RP. Anal. Biochem. 1991;198:228–237. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(91)90418-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).(a) Prathapan S, Yang SI, Seth J, Miller MA, Bocian DF, Holten D, Lindsey JS. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2001;105:8237–8248. [Google Scholar]; (b) Yang SI, Li J, Cho HS, Kim D, Bocian DF, Holten D, Lindsey JS. J. Mater. Chem. 2000;10:283–296. [Google Scholar]

- (19).Demas JN. (Measurement of Photoluminescence) In: Mielenz KD, editor. Optical Radiation Measurements. V3. Academic Press; New York: 1982. pp. 195–248. [Google Scholar]

- (20).(a) Becke AD. Phys. Rev. A. 1988;38:3098–3100. doi: 10.1103/physreva.38.3098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Becke AD. J. Chem. Phys. 1992;97:9173–9177. [Google Scholar]; (c) Becke AD. J. Chem. Phys. 1992;96:2155–2160. [Google Scholar]; (d) Becke AD. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98:5648–5652. [Google Scholar]; (e) Becke AD. J. Chem. Phys. 1996;104:1040–1046. [Google Scholar]

- (21).Miehlich B, Savin A, Stoll H, Preuss H. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1989;157:200–206. [Google Scholar]

- (22).Foresman JB, Frisch E. Exploring chemistry with electronic structure methods. Gaussian Inc.; 2000. 2nd ed. [Google Scholar]

- (23).(a) Miyahara T, Tokita Y, Nakatsuji H. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2001;105:7341–7352. [Google Scholar]; (b) Miyahara T, Nakatsuji H, Hasegawa J, Osuka A, Aratani N, Tsuda A. J. Chem. Phys. 2002;117:11196–11206. [Google Scholar]; (c) Nakajima T, Nakatsuji H. Chem. Phys. 1999;242:177–193. [Google Scholar]; (d) Nakatsuji H. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1978;59:362–364. [Google Scholar]; (e) Nakatsuji H, Hirao K. J. Chem. Phys. 1978;68:2053–2065. [Google Scholar]; (f) Nakatsuji H. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1991;177:331–337. [Google Scholar]

- (24).Martin CH, Birge RR. J. Phys. Chem. A. 1998;102:852–860. [Google Scholar]

- (25).Ren L, Martin CH, Wise KJ, Gillespie NB, Luecke H, Lanyi JK, Spudich JL, Birge RR. Biochemistry. 2001;40:13906–13914. doi: 10.1021/bi0116487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Montgomery JA, Jr., Vreven T, Kudin KN, Burant JC, Millam JM, Iyengar SS, Tomasi J, Barone V, Mennucci B, Cossi M, Scalmani G, Rega N, Petersson GA, Nakatsuji H, Hada M, Ehara M, Toyota K, Fukuda R, Hasegawa J, Ishida M, Nakajima T, Honda Y, Kitao O, Nakai H, Klene M, Li X, Knox JE, Hratchian HP, Cross JB, Bakken V, Adamo C, Jaramillo J, Gomperts R, Stratmann RE, Yazyev O, Austin AJ, Cammi R, Pomelli C, Ochterski JW, Ayala PY, Morokuma K, Voth GA, Salvador P, Dannenberg JJ, Zakrzewski VG, Dapprich S, Daniels AD, Strain MC, Farkas O, Malick DK, Rabuck AD, Raghavachari K, Foresman JB, Ortiz JV, Cui Q, Baboul AG, Clifford S, Cioslowski J, Stefanov BB, Liu G, Liashenko A, Piskorz P, Komaromi I, Martin RL, Fox DJ, Keith T, Al-Laham MA, Peng CY, Nanayakkara A, Challacombe M, Gill PMW, Johnson B, Chen W, Wong MW, Gonzalez C, Pople JA. Gaussian, Inc.; Wallingford CT: 2004. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.