Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the outcome of artificial anal sphincter implantation for severe fecal incontinence in 37 consecutive patients operated on in a single institution from 1993 through 2001.

Summary Background Data

Implantation of an artificial anal sphincter is proposed in severe fecal incontinence when local treatment is unsuitable or has failed. The results of this technique have not been determined yet, and its place among the various operative procedures is still debated.

Methods

Artificial anal sphincters were implanted in 37 patients from 1993 through 2001. All patients had complete fecal incontinence and had failed to respond to medical treatment. Median duration of incontinence was 16 years. The causes of incontinence were sphincter disruption (19 patients), hereditary malformations (2 patients), and neurologic disease (16 patients). Six patients had had previous surgery for fecal incontinence. Assessment was made by physical examination (anal continence, rectal emptying) and anorectal manometry.

Results

In the first 12 patients, six devices had to be removed (50%); the cause of failure was found in all cases, and this allowed contraindications to be defined. Among the next 25 patients, 23 had an uncomplicated postoperative follow-up, and 5 developed seven complications: control pump change (n = 3), balloon migration (n = 1), and major rectal emptying difficulties in patients with obstructive internal rectal procidentia (n = 2). The artificial anal sphincter had to be removed definitively in three cases, representing the failure rate of this technique in the authors’ experience (12%); two other devices had to be removed temporarily and the patients are awaiting reimplantation. In this latter group of 25 patients, 80% have an activated sphincter: continence for liquid stool is normal in 78.9%, continence for gas in 63.1%. Seven patients have rectal emptying difficulties, minor in five and major in two. Manometric studies showed mean pressures of 110 and 37 cm H2O with closed and open sphincter, respectively, with a mean duration of artificial sphincter opening of 128 seconds.

Conclusions

The long-term functional outcome of artificial anal sphincter implantation for severe fecal incontinence is satisfactory; adequate sphincter function is recovered and the definitive removal rate is low. Good results are directly related to careful patient selection and appropriate surgical and perioperative management after a learning curve of the surgical team.

A number of epidemiologic data emphasize the long-unrecognized and underestimated frequency of fecal incontinence, the prevalence of which is estimated to be 7.8% to 18.4%;1,2 a French study of 3,914 patients concluded that the prevalence is 11%. 3 In view of such figures, fecal incontinence appears as a true public health issue, accounting for the current awareness of its societal and economic impact.

Surgery often appears to be the only recourse for traumatic fecal incontinence, or the last resort for functional fecal incontinence after failed alternative treatments, especially pelvic floor retraining. Direct sphincter repair is preferred whenever possible: although the short-term outcome is excellent, it deteriorates with time, with only 50% of patients still perfectly continent at 40 months. 4 Postanal repair was abandoned by our team in 1993 in view of its poor outcome, with only 55% satisfactory results achieved at 2 years of follow-up, 5 and deterioration with time. 6 Sacral nerve stimulation, a novel, promising technique, is under evaluation, but it will probably be relevant to only a limited number of patients. 7

In this uncertain surgical context, two fecal continence-restoring techniques have been developed over the last 10 years: the artificial anal sphincter and dynamic graciloplasty. We report our experience with artificial anal sphincters, initiated in 1993 and based on a series of 37 patients managed by the same medical and surgical team. To the best of our knowledge, it is the most important single-institution experience published to date.

METHODS

One hundred seventy-three patients have been operated on for sphincteric fecal incontinence in our institution from January 1990 through April 2001: 104 had direct sphincter repair;4 23 had postanal repair, 5 a technique abandoned in 1993; 9 had sacral nerve stimulation, 7 a technique initiated in 1998; and 37 patients had an artificial sphincter implanted (American Medical Systems, Minneapolis, MN) since 1993. The latter group is evaluated in this study.

We will analyze these patients as two successive groups. The first group, comprising 12 patients (5 men, 7 women; mean age 53.6 years [range 43–63]), represents our early experience from February 1933 through October 1966. Nine of these patients had an artificial urinary sphincter implanted. This 3-year experience allowed us to codify preoperative and postoperative care and the technical surgical precautions to be taken in the operating room and to define the indications and, more importantly, the contraindications to the technique. Outcomes of 8 of these 12 patients have been published previously. 8

The second group, comprising 25 patients (10 men, 15 women; mean age 51.1 years [range 22–73]), up to April 2001, received a true artificial bowel sphincter (first the ABS, then the Acticon Neosphincter), available in the second semester of 1996. The main changes in the occlusive cuff and the control pump were designed to adapt the cuff to the dimensions of the anal canal, to reinforce it so as to better resist efforts when straining, and to provide percutaneous access to the pump so that the pressure applied in the anal canal can be reduced or raised according to anorectal manometry findings. These patients were evaluated and selected according to the criteria currently used on the basis of the past 3 years’ experience.

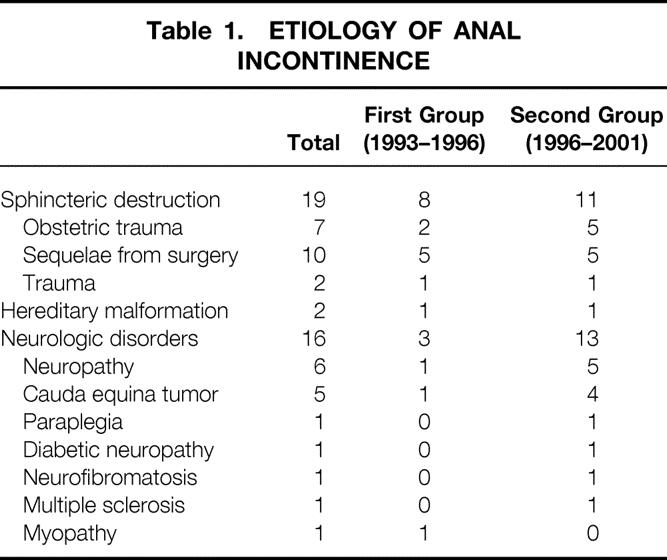

All patients presented with severe and complete incontinence for gas and liquid and solid stool due to various causes (Table 1). Median duration of symptoms was 16 years (range 2–37). Before receiving the implant, all patients had failed to respond to prolonged medical treatment and pelvic floor retraining. Six patients had had previous fecal incontinence surgery: in the first group one sphincteroplasty and one postanal repair and in the second group three sphincteroplasty and one rectopexy. Preoperative assessment included physical examination (evaluation of the anterior perineum and the rectovaginal wall, evidence of rectal prolapse when straining during rectal digital examination), anal endosonography, anorectal manometry, defecographic studies for rectal prolapse or anterior rectocele, electrophysiologic testing, and colonic transit time for transit constipation. Direct local repair was contraindicated because sphincter destruction was too extensive, and since 1998 sacral nerve stimulation was considered impossible either on initial examination or after negative sacral nerve stimulation testing. All patients were thoroughly informed about the procedure, the predictable postoperative follow-up, complications, and outcome, and all gave informed consent. If they wished, they were put in touch with a patient who had previously undergone the procedure.

Table 1.ETIOLOGY OF ANAL INCONTINENCE

Preoperative preparation consisted of an orthograde enema on the night and the morning before surgery (1 L iodine solution). For skin preparation, hair was removed using clippers, not shaved.

During the procedure, stringent asepsis was observed, no entrance or exit was permitted into or out of the operating room, the doors were kept closed, and a maximum of 10 persons were present. Antibiotic prophylaxis was given perioperatively but was not the rule postoperatively in the absence of complications.

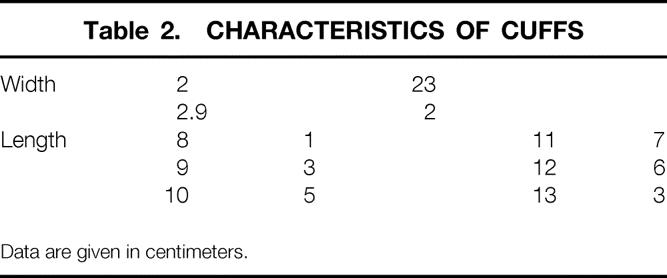

The Acticon Neosphincter is described elsewhere. 8 Cuff characteristics of the last 25 patients are summarized in Table 2: the width was 2 cm in 23 of 25 and the length was 10 to 12 cm in 18 of 25. The decision of the appropriate length was subjective, depending on local anatomic conditions. The best site for implantation of the cuff is the upper limit of the anal canal at the anorectal junction, at a distance from the superficial perineal layers, and if possible covered by the patient’s native external sphincter.

Table 2.CHARACTERISTICS OF CUFFS

Data are given in centimeters.

Colostomies were present at the time of implantation in 3 of 25 patients, and a cover colostomy was performed in 15 cases because of the risk of postoperative perineal sepsis and to protect the sphincter during healing.

Postoperative care is crucial, and the role of nurses important. Perineal cleansing is done twice a day and after each anal emission. In the absence of colostomy, 7 days of parenteral feeding is ordered. In female patients, a vesical catheter is in place for a 7-day period to avoid the perineal soiling associated with micturition. Patients are hospitalized until perineal healing is complete. The median length of stay was 12 days.

The device was kept deactivated for the first 2 months postoperatively, and if a colostomy was present, it was closed 3 to 4 days before activating the artificial anal sphincter. Sphincter function was evaluated by anorectal manometry on the day of activation; patients were trained to use the device under manometric control, thus allowing appropriation of the sphincter and making them feel confident about its functioning. Anal continence was classified into four groups: A, normal continence; B, incontinence for gas; C, incontinence for gas and liquid stools; D, complete incontinence. This scoring system was used in the first years of our experience and we retained it so as to have a homogeneous population.

RESULTS

For the first 12 patients implanted before October 1996, follow-up was more than 5 years. Results of this early experience were disappointing: 6 of the 12 implanted sphincters (50%) had to be removed. The reasons for removal were as follows:

Two patients had perineal sepsis due to postoperative uncontrolled diarrhea (neither had a protective colostomy).

A female patient had perineum and bowel radiation-induced lesions. She had had a coloanal anastomosis completed by postoperative radiation therapy 7 years earlier for rectal cancer. Radiation-induced perineal pain was exacerbated by the cuff, and the sphincter had to be removed despite a successful functional outcome.

Three patients had postoperative perineal erosion that did not heal. In all three, the perineum was destroyed and severely scarred.

A colostomy had to be created in another patient due to poor functional outcome: the patient was incontinent for gas and liquid stool. This woman had previously undergone Babcock-Bacon abdominotransanal amputation. No reservoir was present on the descended colon, whose maximal tolerable volume was less than 100 mL on anorectal manometry, resulting in an insufficient pressure gradient between the neorectum pressure and the normal pressure exerted by the artificial sphincter.

Thus, 7 of the first 12 patients (58%) were failures, but in all cases analysis explained these failures.

The results achieved in these first 12 patients were taken into account for the selection of the following 25 patients, who received implants from November 1996 through April 2001. Follow-up was more than 6 months for all these patients: mean follow-up was 34.1 (range 7–60) months. Postoperative follow-up was uncomplicated in 23 cases. Two early complications occurred in the postoperative period: one inguinal abscess, which healed on local treatment, and one rectal wound requiring removal of the cuff, which was secondarily reimplanted 6 months later with successful outcome. In one patient, colostomy closure was complicated by an intra-abdominal abscess that healed after drainage.

Seven late complications occurred in five patients. In three, the control pump had to be replaced (unexplained dysfunction at 4 months, erosion through the labia majora at 20 months, erosion through the scrotum at 28 months). In one patient, the balloon was relocated after subcutaneous migration; it was reimplanted intraperitoneally. In one patient, the tube eroded through the skin between the inguinal region and the perineum; it was returned into the subcutaneous adipose tissue as an emergency procedure. Two patients developed obstructive internal rectal procidentia, which slipped into the occlusive cuff of the sphincter, leading to major fecal evacuation difficulties. These two patients underwent reoperation. One underwent rectopexy associated with left colectomy because of severe transit constipation, as shown by colonic transit time at 5 months postoperatively. The other underwent rectopexy at 10 months postoperatively.

Overall, 5 of 25 sphincters (20%) were removed. Three (12%) were removed permanently, two because of sepsis (at 10 and 13 months) and one because of perineal erosion at 7 months. Two were removed temporarily, both due to perineal erosion at 20 and 49 months. The cuff alone was removed, with the control pump and the reservoir left in place; reimplantation of the cuff is planned.

Therefore, in our experience, the definitive failure rate of the technique is currently 12%.

Functional outcome was assessed in the 20 other patients. In 19 patients the sphincters are activated. In one patient the sphincter has been deactivated with a defunctioning colostomy following severe multiple trauma due to an accident, with the patient still undergoing treatment and rehabilitation.

Fecal continence in these 19 patients is as follows. All 19 (100%) are continent for solid stool and have never experienced leakage since implantation. Fifteen (78.9%) are continent for liquid stool: four experience leakage during diarrhea episodes, either intermittently (n = 2) or regularly (n = 2). Twelve (63.1%) are continent for gas.

According to the scoring system, 100% of patients were completely incontinent before surgery (score D). After implantation of the Acticon Neosphincter, 63.1% of patients were completely continent (score A) and 15.8% were incontinent for gas (score B); thus, 78.9% of our patients were considered to have a good result. Twenty-one percent were incontinent for gas and liquid stools (score C) and were considered failures.

Seven patients (36.8%) have reported emptying difficulties. In five cases, regular enemas and laxatives allow satisfactory rectal evacuation, but in two cases, major rectal emptying disorders cause abdominal discomfort due to fecaloma formation despite daily enemas.

Manometric evaluation showed mean pressures of 110 and 37 cm H2O with closed and open sphincter, respectively. No difference was observed between patients continent for gas and/or liquid stool, and incontinent patients. Mean duration of sphincter opening was 128 seconds (range 45–320). In four patients it was less than 60 seconds, and in two others it was greater than 240 seconds. Overall duration of sphincter opening was significantly shorter (47 seconds) in patients with emptying difficulties than in patients free of such problems (178 seconds) (P = .002). In one female patient, sphincter closure pressure was reduced from 140 to 110 cm H2O by percutaneous puncture of the septum at the top of the pump under manometric control.

DISCUSSION

The experience of a homogeneous team is reported in the present study. It includes our early experience and shows the evolution of our ideas since 1993. The outcome of the first 12 patients was very disappointing, with 58% failures; it is similar to the long-term results reported by Christiansen et al in patients operated on between 1987 and 1993. 9 Indeed, a urinary sphincter was used in 9 of the first 12 cases, but use of an inadequate prosthesis does not account for these poor results: they are due to inappropriate selection of patients at a time before contraindications to the artificial sphincter had been defined. Our failures thus allowed us to specify the contraindications to the technique:

A destroyed or severely scarred anterior perineum (Fig. 1) predicts difficult healing and risk of perineal erosion. This accounted for three of the six removals in the first 12 patients and one of three permanent removals in the following 25 patients.

Perineal radiation-induced lesions may cause postoperative pain, making the occlusive cuff unbearable.

Diarrheic transit requiring a temporary cover colostomy during perineal healing because of the postoperative risk of perineal sepsis; this accounted for two of the six removals in the first 12 patients. Creation of a colostomy in the presence of any potential postoperative perineal risk (diarrhea, diabetes mellitus, steroid therapy) is one of the reasons why no postoperative septic complications occurred in the following 25 patients. We used defunctioning colostomy in a high proportion of patients (12/22 in the second group of patients) as it is necessary to protect perineal healing by a colostomy whenever there is a potential perineal risk. We consider diarrhea to carry a high risk of perineal sepsis in the postoperative period because nursing management is too difficult under these circumstances. In contrast, one patient still has a colostomy (not due to the Acticon Neosphincter) and only one complication due to colostomy closure was observed; the benefit of colostomy is, in fact, greater than the risk of complications.

The absence of a rectal reservoir: a maximal tolerable volume less than 150 mL is a risk factor for poor functional outcome resulting from an insufficient pressure gradient between the rectal pressure and the closure pressure of the artificial sphincter. In such cases, a rectal neoreservoir should be created before implanting the sphincter: this was done in a female patient operated on in another institution (and not included in the present series for that reason).

Figure 1. Example of destroyed and scarred perineum, which is a contraindication to implantation of the Acticon Neosphincter.

On the other hand, the presence of perineal and/or perianal sclerosis is not a contraindication to implantation of the device. It does not technically interfere with the implantation of the artificial sphincter and does not impair the outcome.

Late perineal erosion may occur after implantation at one of two sites. It may occur at the level of the perineum, since the cuff tends to slide down and reach the surface when straining to achieve complete rectal emptying. This was observed at 20 months postoperatively in a patient with spina bifida. Erosion may also occur at the level of the anal canal, as was observed in one of four patients at 49 months postoperatively; ischemia due to excessive pressure in the anal canal could produce this complication. 10

Our youngest patient was 22 years of age, the oldest 73. Age is not a contraindication: we operated on a 15-year-old girl in another institution, and there are reports of artificial anal sphincter implantation in children in the literature. 11 In patients older than 70 years, the indication depends on the patient’s diathesis: physiologic conditions and psychological and intellectual status. Difficulties in achieving easy rectal emptying occurred in seven patients. This type of disorder is usually minor and resolved by the use of enemas and laxatives. However, they may be severe and impair the quality of life and gastrointestinal comfort, as observed in two patients. Preoperative assessment by defecography and colonic transit time of causes likely to cause such postoperative problems is mandatory: complete rectal prolapse, internal rectal procidentia, or anterior rectocele should be corrected before implantation of an Acticon Neosphincter. Rectopexy with or without left hemicolectomy had to be performed in two women with internal rectal prolapse after implantation of the sphincter because this evaluation had not been carried out preoperatively. From a manometric standpoint, the Acticon Neosphincter reproduces a physiologic pressure of about 80 cm H2O. In our experience, residual pressure after sphincter opening is about 37 cm H2O, reflecting a cuff effect due to the mere presence of the cuff and the patient’s native sphincter activity. Contraction and relaxation of the internal sphincter account for some cases of leakage and incontinence for gas and liquid stool. In these patients, continence could be improved by paralyzing the native internal sphincter (for instance, by injection of botulin).

A short cuff and short opening time of the sphincter are correlated with poor rectum emptying 12: the cuffs implanted in the seven patients with rectal emptying difficulties were 10 cm or shorter, and manometric assessment showed that the duration of sphincter opening was short (45 seconds on average) and significantly shorter than in patients free of such difficulties (P = .002). Therefore, cuffs 10 cm or less should not be used. The quality of continence is not correlated with cuff height (2 or 2.9 cm), and for that reason we prefer 2-cm cuffs as easier to implant into the perineum. However, we cannot explain why the duration of cuff opening varies from 45 to 320 seconds in our series.

Hereditary malformations (spina bifida or imperforate anus), certain neurologic conditions (cauda equina tumor, diabetic neuropathy), and extensive (>50%), irreparable destruction of the external sphincter from any cause (obstetric, traumatic, or surgical) are definite indications for the artificial anal sphincter. In neuropathic fecal incontinence without sphincter defect on anal endosonography, the decision is not so easy. In active fecal incontinence, sacral nerve stimulation testing is performed first: if it is positive, a neurostimulator is implanted. Conversely, a negative test and the presence of passive anal incontinence indicate an artificial anal sphincter, because in our experience the outcome of sacral nerve stimulation in passive fecal incontinence is disappointing. 7 This therapeutic strategy has been used in our institution since 1998, when we initiated sacral nerve stimulation, and is relevant only to our most recent patients. Lastly, the indication may be discussed in patients with fecal incontinence with sphincter disruption amenable to repair by sphincteroplasty, but it cannot be discussed in the presence of pudendal neuropathy, extensive disruption of the internal sphincter, and hypotonia of the anal canal, which carry a poor functional prognosis of direct sphincter repair. 4 Dynamic graciloplasty is the alternative to the artificial anal sphincter; indications are not clearly different, and outcome is usually considered to be similar. However, the latest multicenter study by Baeten et al 13 showed poorer results than those reported in our series. Furthermore, the simplicity of use of the Acticon Neosphincter is an asset: it ensures reproducible results and wide diffusion of the device. Lastly, the artificial anal sphincter costs 4,335 euros, which is much less than the cost of dynamic graciloplasty.

In conclusion, the Acticon Neosphincter is an efficacious and reliable treatment for severe fecal incontinence. It will be essential to evaluate the late results of our patients because the follow-up in this study was relatively short. Nevertheless, these results are satisfactory in carefully selected patients after a learning curve of the surgical team.

Footnotes

Correspondence: Prof. Francis Michot, MD, PhD, Service de Chirurgie Digestive, Hôpital Charles Nicolle 76031 Rouen, France.

E-mail: francis.michot@chu-rouen.fr

Accepted for publication May 23, 2002.

References

- 1.Vaizey CJ, Kamm MA, Gold DM, et al. Clinical, physiological and radiological study of the new purpose-designed artificial bowel sphincter. Lancet 1998; 352: 105–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jorge JMN, Wexner SD. Etiology and management of fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum 1993; 36: 77–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Denis P, Bercoff E, Bizien MF, et al. Etude de la prévalence de l’incontinence anale chez l’adulte. Gastroentérol Clin Biol 1992; 16: 344–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karoui S, Leroi AM, Koning E, et al. Results of sphincteroplasty in 86 patients with anal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum 2000; 43: 813–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Le Blanc I, Michot F, Ducrotte P, et al. In case of reeducation failure, should postanal repair be the treatment of idiopathic fecal incontinence. Dig Surg 1993; 10: 39–42. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Setti-Carraro P, Kamm MA, Nicholls RJ. Long-term results of postanal repair for neurogenic faecal incontinence. Br J Surg 1994; 81: 140–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leroi AM, Michot F, Grise P, et al. Effect of sacral nerve stimulation in patients with fecal and urinary incontinence? Dis Colon Rectum 2001; 44: 779–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lehur PA, Michot F, Denis P, et al. Results of artificial anal sphincter in severe anal incontinence. Report of 14 consecutive implantations. Dis Colon Rectum 1996; 39: 1352–1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christiansen J, Rasmussen O, Lindorff-Larsen K. Long-term results of artificial anal sphincter implantation for severe anal incontinence. Ann Surg 1999; 230: 45–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hajivassiliou CA, Finlay IG. Effect of a novel prosthetic anal neosphincter on human colonic blood flow. Br J Surg 1998; 85: 1703–1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Riedel JG, Festge OA. Eine neue behandlungmethode bei schwerer stuhlinkontinenz im kindesalter. Chirurg 1999; 70: 935–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Savoye G, Leroi AM, Denis P, et al. Manometric assessment of an artificial bowel sphincter. Br J Surg 2000; 87: 586–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baeten CGMI and the Dynamic Graciloplasty Group. Safety and efficacy of dynamic graciloplasty for fecal incontinence. Report of a prospective, multicenter trial. Dis Colon Rectum 2000; 43: 743–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]