Abstract

Objective

To assess whether elective colon and rectal surgery can be safely performed without preoperative mechanical bowel preparation.

Summary Background Data

Mechanical bowel preparation is routinely done before colon and rectal surgery, aimed at reducing the risk of postoperative infectious complications. However, in cases of penetrating colon trauma, primary colonic anastomosis has proven to be safe even though the bowel is not prepared.

Methods

Patients undergoing elective colon and rectal resections with primary anastomosis were prospectively randomized into two groups. Group A had mechanical bowel preparation with polyethylene glycol before surgery, and group B had their surgery without preoperative mechanical bowel preparation. Patients were followed up for 30 days for wound, anastomotic, and intra-abdominal infectious complications.

Results

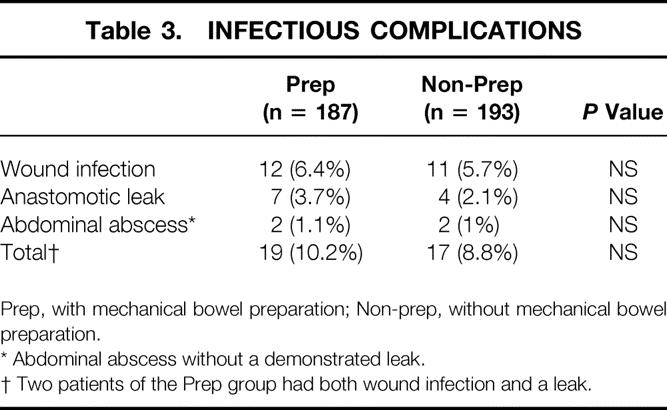

Three hundred eighty patients were included in the study, 187 in group A and 193 in group B. Demographic characteristics, indications for surgery, and type of surgical procedure did not significantly differ between the two groups. Colo-colonic or colorectal anastomosis was performed in 63% of the patients in group A and 66% in group B. There was no difference in the rate of surgical infectious complications between the two groups. The overall infectious complications rate was 10.2% in group A and 8.8% in group B. Wound infection, anastomotic leak, and intra-abdominal abscess occurred in 6.4%, 3.7%, and 1.1% versus 5.7%, 2.1%, and 1%, respectively.

Conclusions

These results suggest that elective colon and rectal surgery may be safely performed without mechanical preparation.

In the first half of the 20th century, mortality from colon and rectal surgery often exceeded 20%, 1 mainly attributed to sepsis. Modern surgical techniques and improved perioperative care have significantly lowered the mortality rate. Infectious complications, however, still are a major cause of morbidity in colorectal surgery, leading to increased cost, prolonged hospital stay, and occasional mortality. 2

Mechanical bowel preparation is aimed at cleaning the large bowel of fecal content, thereby reducing the rate of infectious complications following surgery. Traditionally, bowel cleansing was achieved using enemas in combination with oral laxatives. 3 More recently, oral cathartic agents to induce diarrhea and cleanse the bowel from solid feces were developed. These new bowel preparation agents, such as polyethylene glycol and sodium phosphate, provide superior cleansing compared to the more traditional methods 4–6 and are used by most surgeons in preparation for colorectal surgery. 7–9 The practice of bowel cleansing before colorectal surgery has became a surgical dogma, and primary colonic anastomosis is considered unsafe in the face of an unprepared bowel. There is, however, a paucity of data showing that mechanical bowel preparation by itself, separately from other operative and perioperative measures, actually reduces the rate of infectious complications.

In urgent colon surgery for penetrating trauma, recent studies have shown that primary colonic anastomosis is safe even though mechanical bowel preparation is not performed before surgery. 10,11 These data therefore may bring into question the utility of mechanical bowel preparation in elective colon and rectal surgery.

The aim of this study was to assess whether elective colon and rectal surgery may be safely performed without preoperative mechanical bowel preparation.

METHODS

Patients undergoing elective colon and rectal surgery with primary anastomosis in two university-affiliated departments of surgery between 1997 and 2000 were prospectively randomized by individual computer-generated randomization into two groups. Patients in Group A (the “prep” group) received mechanical bowel preparation with one gallon of polyethylene glycol 12 to 16 hours before surgery, and Group B (the “non-prep” group) had no preoperative mechanical bowel preparation. All patients were allowed to have a regular diet until midnight the evening before surgery (patients in the prep group usually took their mechanical preparation after the last solid meal). All of the patients received preoperative oral antibiotics (three doses of neomycin and erythromycin), and perioperative broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics, which were continued for at least 24 hours postoperatively. Surgeons were allowed to continue the prophylactic intravenous antibiotics for more then 1 day, and the length of prophylactic treatment was recorded.

Patients undergoing rectal surgery were given one Fleet enema (C.B. Fleet Inc., Lynchburg, VA) on the day of surgery to avoid extrusion of stool when using a transanally inserted stapling device.

Patients with tumors smaller than 2 cm were excluded from the study, as palpation of small tumors may be difficult in an unprepared bowel, and these patients may require intraoperative colonoscopy to identify these lesions. Patients who required a diverting stoma proximal to the anastomosis and those who were found to have an abdominal abscess at the time of surgery were also excluded from the data analysis.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (Helsinki committee), and all patients gave their informed consent before randomization in the study.

Data relative to patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics, operative procedures and findings, and 30-day postoperative follow-up were prospectively entered in a Microsoft Access database, and main endpoints entry was rechecked for accuracy. The main outcome was the rate of postoperative infectious complications, such as wound infection, anastomotic leak, and intra-abdominal abscess. Wound infection was defined as a wound requiring partial or complete opening for drainage of purulent collection, or erythema requiring initiation of antibiotic treatment. Anastomotic leak was identified if demonstrated by imaging or documented in surgery, or if fecal drainage was evident through a perianastomotic drain. Abdominal abscess was defined as fluid collection demonstrated by computed tomography scan, in conjunction with elevated temperature or white blood cell count. Secondary outcomes were the overall rate of complications and the quality of bowel preparation as assessed by the operating surgeon.

Statistical analysis was performed using the Fisher exact test or unpaired t test, as appropriate (GraphPad InStat, San Diego, CA), and probability values of less than 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

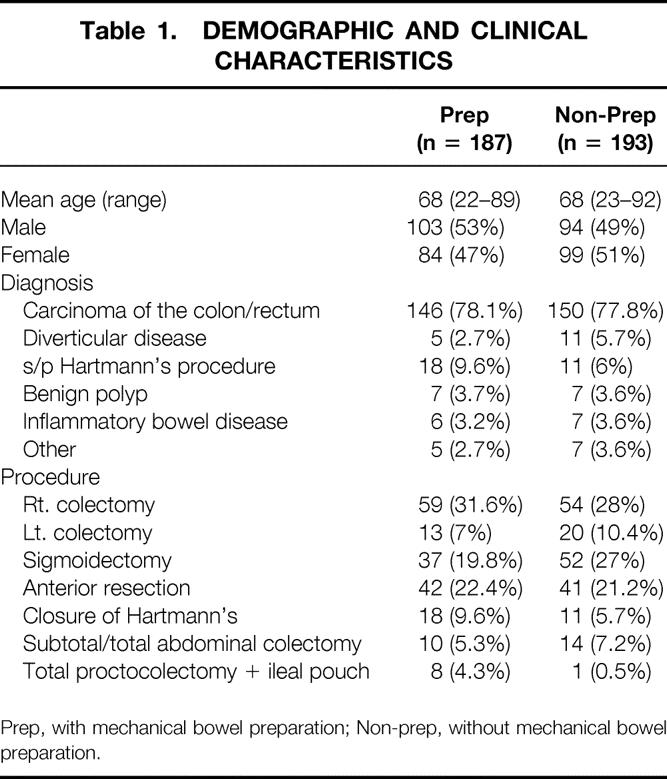

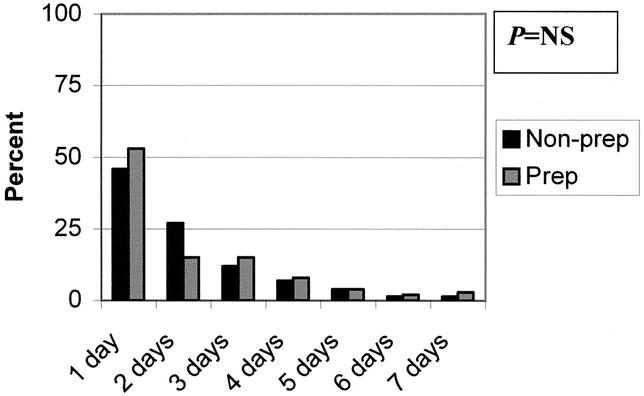

Four hundred fifteen patients were entered into the study between July 1997 and July 2000. Twenty-nine patients were excluded after randomization due to the intraoperative exclusion criteria (18 had abdominoperineal resection and 11 had a proximal stoma). Six patients withdrew their consent before surgery, leaving 380 patients for the data analysis. One hundred eighty-seven patients had their surgery with preoperative mechanical bowel preparation, while 193 did not have mechanical preparation. Demographic characteristics, indications for surgery, and type of surgery did not significantly differ between the two groups (Table 1). Nearly two thirds of the patients in both groups had surgery with colo-colonic, colorectal, or coloanal anastomosis (63% in the prep group and 66% in the non-prep group). The median length of postoperative antibiotic treatment was 2.0 days in the prep group and 2.5 days in the nonprep group (P = NS). The distribution of length of antibiotic prophylaxis is shown in Figure 1.

Table 1. DEMOGRAPHIC AND CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Prep, with mechanical bowel preparation; Non-prep, without mechanical bowel preparation.

Figure 1. Length of prophylactic antibiotic treatment. The bars represent the percentage of the patients in each group. Prep, with mechanical bowel preparation (n = 187); Non-prep, without mechanical bowel preparation (n = 193).

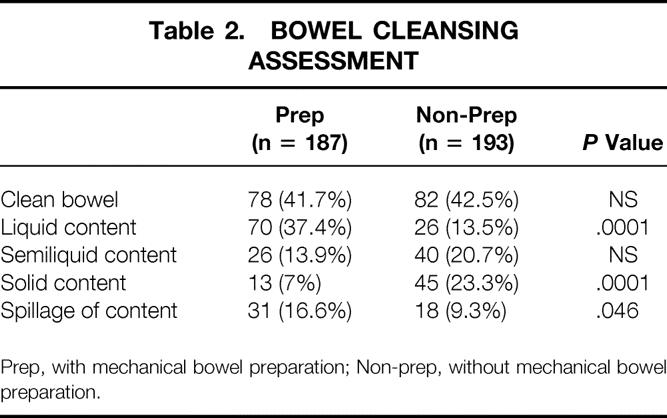

Solid content in the colon was found in surgery in nearly a quarter of the patients in the non-prep group, and liquid and semiliquid contents were the most common findings in the prep group. Spillage of bowel content during surgery was significantly more common in the prep compared to the non-prep group (Table 2).

Table 2. BOWEL CLEANSING ASSESSMENT

Prep, with mechanical bowel preparation; Non-prep, without mechanical bowel preparation.

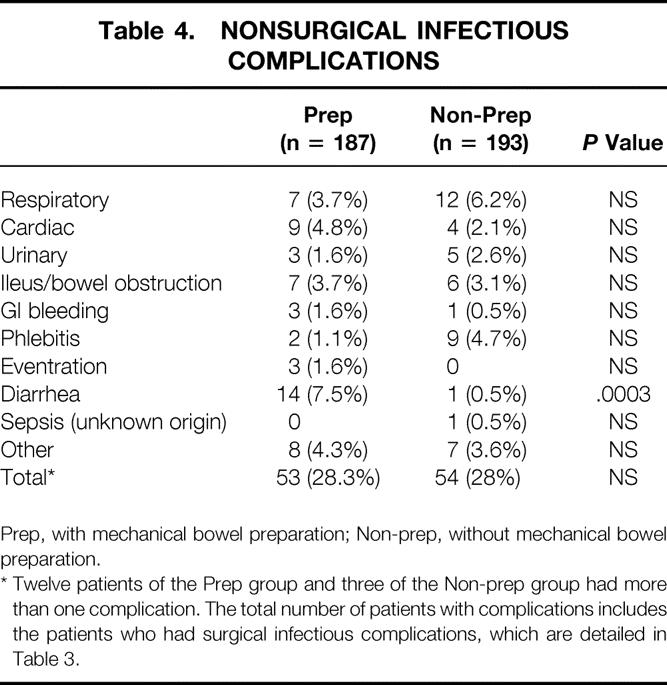

When assessing the main outcomes of this study, there was no significant difference in the rate of postoperative wound infections, clinical anastomotic leaks, or intra-abdominal abscesses between the prep and the non-prep group (Table 3). The surgical infectious complications rate was 10.2% in the prep group and 8.8% in the non-prep group. The overall complications rate was not significantly different between the two groups (28.3% in the prep group, 28.0% in the non-prep group;Table 4). Diarrhea in the early postoperative period was significantly more common in the prep group compared to the non-prep group (P = .0003).

Table 3. INFECTIOUS COMPLICATIONS

Prep, with mechanical bowel preparation; Non-prep, without mechanical bowel preparation.

* Abdominal abscess without a demonstrated leak.

† Two patients of the Prep group had both wound infection and a leak.

Table 4. NONSURGICAL INFECTIOUS COMPLICATIONS

Prep, with mechanical bowel preparation; Non-prep, without mechanical bowel preparation.

* Twelve patients of the Prep group and three of the Non-prep group had more than one complication. The total number of patients with complications includes the patients who had surgical infectious complications, which are detailed in Table 3.

There was no significant difference in the average days to the first bowel movement and the length of hospital stay between the prep group and the non-prep group (3.8 days vs. 4.2 days, and 8.2 days vs. 8.1 days, respectively).

Mortality occurred in three patients in each group (1.6% in the prep group, and 1.55% in the non-prep group). One patient in each group died due to sepsis from an anastomotic leak. Although none of these patients underwent an autopsy, none of the other four deaths was attributed to surgical infectious complications (1 cardiac, 3 respiratory).

DISCUSSION

Preparation for elective colon and rectal surgery with mechanical cleansing and antibiotic prophylaxis, in conjunction with improved surgical techniques and advances in perioperative care, served to reduce the rate of infectious complications in colorectal surgery. Although mechanical bowel preparation before elective colorectal surgery has become a surgical dogma, there is a paucity of scientific evidence demonstrating the efficacy of this practice in reducing the rate of infectious complications.

Whereas some animal studies have shown that mechanical preparation improved anastomotic bursting strength 12,13 and decreased septic complications, 12 others failed to find a difference between groups of animals with or without bowel preparation. 14 Further evidence questioning the utility of mechanical bowel preparation in colorectal surgery comes from the literature regarding the management of urgent cases, such as patients with penetrating colonic trauma or acute colonic obstruction. In cases of penetrating trauma, prospective randomized studies have shown that primary colonic anastomosis is safe 15,16 even though the colon is not prepared, the mechanism of injury is not as controlled as in elective cases, and there is often a delay between the injury and the repair. These studies have led to a change in the standard of care of penetrating colonic trauma toward primary colonic repair. 10,11

In cases of acute colonic obstruction, resection with primary anastomosis in one stage is not the common practice, as the colon is not prepared. Advanced techniques, such as on-table bowel lavage 17,18 or colonic metallic stents, 19,20 have been used in an effort to allow mechanical bowel cleansing before primary anastomosis. Few authors, however, have challenged the dogma that colon resection with primary anastomosis is unsafe in patients with obstructing colon lesions. Few series suggested that anastomosis between the small bowel and the colon, as performed in right or subtotal colectomy, may be safe without mechanical preparation, 21,22 since this type of anastomosis avoids the stool column proximal to the anastomosis. In a multicentric trial, 23 97 patients with malignant left colonic obstruction were randomized to have either a segmental colon resection with on-table bowel lavage or a subtotal colectomy. The rates of intra-abdominal sepsis and anastomotic leaks did not significantly differ between the two groups. Other authors have suggested that colo-colonic anastomosis may also be safe in an unprepared bowel in the face of an obstructed colon. 24–26 Recently, Naraynsingh et al. 27 reported a prospective series of 58 unselected patients with left colonic obstruction. All underwent segmental colon resection with primary colo-colonic anastomosis, without a proximal diverting stoma. There was one case of anastomotic leak and one mortality unrelated to infection.

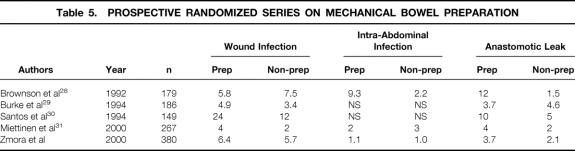

Four published studies 28–31 have prospectively randomized patients undergoing elective colon and rectal surgery to having mechanical bowel preparation or no mechanical preparation. Although all of the prior studies are smaller in numbers then the current study, they also failed to show a benefit to mechanical bowel preparation in reducing the rate of infectious complications and anastomotic leaks (Table 5).

Table 5. PROSPECTIVE RANDOMIZED SERIES ON MECHANICAL BOWEL PREPARATION

Although the new agents used for mechanical bowel preparation such as polyethylene glycol and sodium phosphate are strong cathartic agents, the colon is frequently not completely clean and dry at the time of surgery. In our study, fluid or semifluid stool was found in 51.3% of the patients of the prep group. When preparation is done for colonoscopy, liquid stool can be easily aspirated to provide adequate cleansing for a safe and effective colonoscopy. In contrast, when used as a preparation for surgery, it is more difficult to control liquid than solid stool, which may lead to the significantly higher rate of intraoperative spillage of contaminated bowel content. When mechanical bowel preparation is used, the use of a clear liquid diet before surgery, in conjunction with the cathartic agent, may potentially improve the quality of the preparation and reduce the rate of liquid colonic content.

Mechanical bowel preparation is not harmless. It almost invariably causes significant discomfort to the patient, including nausea, abdominal bloating, and diarrhea. 4–6 Mechanical bowel preparation is also associated with electrolyte imbalance and dehydration, 4,5,32–34 which may complicate the induction of anesthesia and perioperative care. Thus, in our view, mechanical bowel preparation should be treated as a medication and used only when indicated.

Assessing the role of mechanical bowel preparation separately from other measures used to reduce the rate of infectious complications is a difficult task. Ideally, all the measures, including the surgical technique, should be maintained constant, while the variable component should be randomized into “treatment” or “no treatment” groups. Assuming an infectious complications rate of 10%, for a prospective study that will be able to detect a difference of 5% in infection rate, in a one-tailed statistical test, assuming an alpha level of 0.05, with a statistical power of 90%, 770 patients are required to be randomized to each group, or a total of 1,540 patients in the study. It seems impossible for one team to enroll such a number of patients into this kind of study in a reasonable period. Multicenter studies allow patient accrual but at the expense of heterogeneous operative and perioperative techniques, which may be the most important factors influencing the surgical outcome.

The results of this study strongly suggest that elective colon and rectal surgery may be safely performed without the use of routine mechanical bowel preparation. Bowel cleansing should therefore be used selectively—for instance, in cases where intraoperative colonoscopy is likely to be required. Multicenter studies, with their limitation of diversity of techniques, should provide data on the reproducibility of these results to support a change in this time-honored surgical practice.

Footnotes

Presented at the Biennial Congress of the International Society of University Colon and Rectal Surgeons, Osaka, Japan, April 14–18, 2002.

Correspondence: Oded Zmora, MD, Department of Surgery and Transplantation, Sheba Medical Center, Tel-Hashomer 52621, Isreal.

E-mail: ozmora@post.tau.ac.il

Accepted for publication February 25, 2002.

References

- 1.Glenn F, McSherry CK. Carcinoma of the distal large bowel: 32-year review of 1,026 cases. Ann Surg. 1966; 163: 838–849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brachman PS, Dan BB, Haley RW, et al. Nosocomial surgical infections: incidence and cost. Surg Clin North Am. 1980; 60: 15–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keighley MR. A clinical and physiological evaluation of bowel preparation for elective colorectal surgery. World J Surg. 1982; 6: 464–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oliveira L, Wexner SD, Daniel N, et al. Mechanical bowel preparation for elective colorectal surgery. A prospective, randomized, surgeon-blinded trial comparing sodium phosphate and polyethylene glycol-based oral lavage solutions. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997; 40: 585–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen SM, Wexner SD, Binderow SR, et al. Prospective, randomized, endoscopic-blinded trial comparing precolonoscopy bowel cleansing methods. Dis Colon Rectum. 1994; 37: 689–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoshioka K, Connolly AB, Ogunbiyi OA, et al. Randomized trial of oral sodium phosphate compared with oral sodium picosulphate (Picolax) for elective colorectal surgery and colonoscopy. Dig Surg. 2000; 17: 66–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beck DE, Fazio VW. Current preoperative bowel cleansing methods. Results of a survey. Dis Colon Rectum. 1990; 33: 12–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Solla JA, Rothenberger DA. Preoperative bowel preparation. A survey of colon and rectal surgeons. Dis Colon Rectum. 1990; 33: 154–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nichols RL, Smith JW, Garcia RY, et al. Current practices of preoperative bowel preparation among North American colorectal surgeons. Clin Infect Dis. 1997; 24: 609–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Curran TJ, Borzotta AP. Complications of primary repair of colon injury: literature review of 2,964 cases. Am J Surg. 1999; 177: 42–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conrad JK, Ferry KM, Foreman ML, et al. Changing management trends in penetrating colon trauma. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000; 43: 466–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Dwyer PJ, Conway W, McDermott EW, et al. Effect of mechanical bowel preparation on anastomotic integrity following low anterior resection in dogs. Br J Surg. 1989; 76: 756–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Irvin TT, Bostock T. The effects of mechanical preparation and acidification of the colon on the healing of colonic anastomoses. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1976; 143: 443–447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schein M, Assalia A, Eldar S, et al. Is mechanical bowel preparation necessary before primary colonic anastomosis? An experimental study. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995; 38: 749–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sasaki LS, Allaben RD, Golwala R, et al. Primary repair of colon injuries: a prospective randomized study. J Trauma. 1995; 39: 895–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gonzalez RP, Merlotti GJ, Holevar MR. Colostomy in penetrating colon injury: is it necessary? J Trauma. 1996; 41: 271–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murray JJ, Schoetz DJ Jr, Coller JA, et al. Intraoperative colonic lavage and primary anastomosis in nonelective colon resection. Dis Colon Rectum. 1991; 34: 527–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stewart J, Diament RH, Brennan TG. Management of obstructing lesions of the left colon by resection, on-table lavage, and primary anastomosis. Surgery. 1993; 114: 502–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tejero E, Fernandez-Lobato R, Mainar A, et al. Initial results of a new procedure for treatment of malignant obstruction of the left colon. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997; 40: 432–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mainar A, De Gregorio Ariza MA, Tejero E, et al. Acute colorectal obstruction: treatment with self-expandable metallic stents before scheduled surgery: results of a multicenter study. Radiology. 1999; 210: 65–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mealy K, Salman A, Arthur G. Definitive one-stage emergency large bowel surgery. Br J Surg. 1988; 75: 1216–1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Torralba JA, Robles R, Parrilla P, et al. Subtotal colectomy vs. intraoperative colonic irrigation in the management of obstructed left colon carcinoma. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998; 41: 18–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Single-stage treatment for malignant left-sided colonic obstruction: a prospective randomized clinical trial comparing subtotal colectomy with segmental resection following intraoperative irrigation. The SCOTIA Study Group (Subtotal Colectomy versus On-table Irrigation and Anastomosis). Br J Surg. 1995;82:1622–1627. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Mealy K, Salman A, Arthur G. Definitive one-stage emergency large bowel surgery. Br J Surg. 1988; 75: 1216–1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dorudi S, Wilson NM, Heddle RM. Primary restorative colectomy in malignant left-sided large bowel obstruction. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1990; 72: 393–395. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.White CM, Macfie J. Immediate colectomy and primary anastomosis for acute obstruction due to carcinoma of the left colon and rectum. Dis Colon Rectum. 1985; 28: 155–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Naraynsingh V, Rampaul R, Maharaj D, et al. Prospective study of primary anastomosis without colonic lavage for patients with an obstructed left colon. Br J Surg. 1999; 86: 1341–1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brownson P, Jenkins S, Nott D, et al. Mechanical bowel preparation before colorectal surgery: results of a prospective randomized trial [abstract]. Br J Surg. 1992; 79: 461–462. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burke P, Mealy K, Gillen P, et al. Requirement for bowel preparation in colorectal surgery. Br J Surg. 1994; 81: 907–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Santos JC Jr, Batista J, Sirimarco MT, et al. Prospective randomized trial of mechanical bowel preparation in patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery. Br J Surg. 1994; 81: 1673–1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miettinen RP, Laitinen ST, Makela JT, et al. Bowel preparation with oral polyethylene glycol electrolyte solution vs. no preparation in elective open colorectal surgery: prospective, randomized study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000; 43: 669–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lieberman DA, Ghormley J, Flora K. Effect of oral sodium phosphate colon preparation on serum electrolytes in patients with normal serum creatinine. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996; 43: 467–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DiPalma JA, Brady CE 3d, Stewart DL, et al. Comparison of colon cleansing methods in preparation for colonoscopy. Gastroenterology. 1984; 86: 856–860. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Habr-Gama A, Bringel RW, Nahas SC, et al. Bowel preparation for colonoscopy: comparison of mannitol and sodium phosphate. Results of a prospective randomized study. Rev Hosp Clin Fac Med Sao Paulo. 1999; 54: 187–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]