Abstract

Objective

To determine the impact of work hour limitations imposed by the 405 (Bell) Regulations as perceived by general surgery residents in New York State.

Summary Background Data

New Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) requirements on resident duty hours are scheduled to undergo nationwide implementation in July 2003. State regulations stipulating similar resident work hour limitations have already been enacted in New York.

Methods

A statewide survey of residents enrolled in general surgery residencies in New York was administered.

Results

Most respondents reported general compliance with 405 Regulations in their residency programs, a finding corroborated by reported work hours and call schedules. Whereas a majority of residents reported improved quality of life as a result of the work hour limitations, a substantial portion reported negative impacts on surgical training and quality and continuity of patient care. Negative perceptions of the impact of duty hour restrictions were more prevalent among senior residents and residents at academic medical centers than among junior residents and residents at community hospitals.

Conclusions

Implementation of resident work hour limitations in general surgery residencies may have negative consequences for patient care and resident education. As surgical residency programs develop strategies for complying with ACGME requirements, these negative consequences must be addressed.

At its June 2002 meeting, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Board of Directors approved new requirements that limit residents to 80 duty hours per week, averaged over a 4-week period. 1 These requirements are scheduled to undergo nationwide implementation on July 1, 2003. During the remainder of this academic year, general surgery residency programs throughout most of the country will need to develop strategies for complying with the new requirements. Residency programs in New York, however, have already been required to comply with similar residency work hour limitations pursuant to state regulations. 2

Adopted in 1989, the “405 (Bell) Regulations” were developed in response to the death of a young woman, Libby Zion, in a New York teaching hospital in 1984. 3,4 The Regulations prohibit hospitals from scheduling residents to work more than 24 hours straight and more than 80 hours per week, averaged over a 4-week period, and provide that residents must be given at least 24 consecutive hours off each week. Surgical residents are exempted from the 80-hour cap if the hospital can document that residents are “generally resting” during their call nights, that residents are scheduled for call no more than every third night, that each call day is followed by at least 16 hours off, and that procedures are in place to immediately relieve a resident who is fatigued due to an unusually active call period. 2

Public support for the 405 Regulations has been predicated on the belief that excessive resident work hours played a causal role in the Zion death, and the adoption of both the 405 Regulations and the new ACGME requirements has been motivated by growing opinion that resident fatigue jeopardizes patient safety. 4,5 For nearly a decade, compliance with the Regulations was uneven and inadequate in many programs, due in part to a lax oversight by an understaffed department of health. 6,7 The Regulations were particularly difficult to implement in the context of surgical residency programs. However, after a series of inspections in 1998 found that all 12 inspected hospitals consistently violated the Regulations, there was a movement for stricter enforcement. 8 Fines were levied on several institutions, and new compliance requirements and penalties for nonadherence were adopted as part of New York’s Health Care Reform Act 2000. Compliance is thought to have improved since 2000, but violations continue to be documented. 5

Resident work hour limitations are argued to have beneficial effects on both patient care and resident quality of life. 9–11 However, relatively few data supporting or refuting this assumption exist. To examine the impact of work hour limitations imposed by the 405 Regulations, we conducted a statewide survey of New York surgical residents. Our goal was to identify specific pitfalls associated with the implementation of resident work hour limitations in the context of surgical residency programs.

METHODS

Survey Instrument Development

We elicited residents’ views using a 29-item structured questionnaire. Topic areas included demographic characteristics; actual and desired duty hours; extent and course of enforcement of the 405 Regulations; changes introduced in the residency program to reduce work hours; impact of program changes on work life, quality of life, quality of training, and patient care; and attitudes toward the 405 Regulations. Attitudinal questions were formatted as 5-point Likert scales. The questionnaire also included space for free-form comments.

Initial drafts of the questionnaire were developed by two investigators (M.J.Z., E.E.W.). These drafts subsequently were revised by an investigator with expertise in survey design (M.M.M.). The draft instrument was pretested on six New York surgical residents at various stages of training, who were debriefed in cognitive interviews focusing on question topics, wording, response categories, and format. The instrument was further refined following the pretesting.

Survey Administration

After the final survey instrument and administration method were approved by the institutional review boards of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and the Harvard School of Public Health, letters were sent to the program directors of each of the 33 general surgery residency programs in New York state. Two program directors refused access to their residents, one because of an adverse outcome from a recent state Department of Health review and the other for “political reasons.”

Surveys were mailed in May 2002 along with a cover letter to all residents in the 31 New York surgical residency programs that agreed to participate in the study (n = 1,037). The survey cover letter contained the standard elements for obtaining informed consent. All responses were anonymous. A postcard containing a numeric identifier was included in the mailing for the sole purpose of tracking respondents and nonrespondents; this card was returned separately from the questionnaire to preserve the anonymity of responses. A second mailing was sent to nonrespondents after 2 weeks, followed by a mailed reminder after 3 weeks. After 5 weeks, residency program directors were asked to send out a general reminder and encouragement to all residents to complete the survey.

Statistical Analysis

Survey responses were coded manually, entered into an Excel spreadsheet, and double-checked for accuracy. Descriptive statistics, t tests, chi-square analyses, and Kruskal-Wallis tests for equality of populations were calculated using the STATA statistical package.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

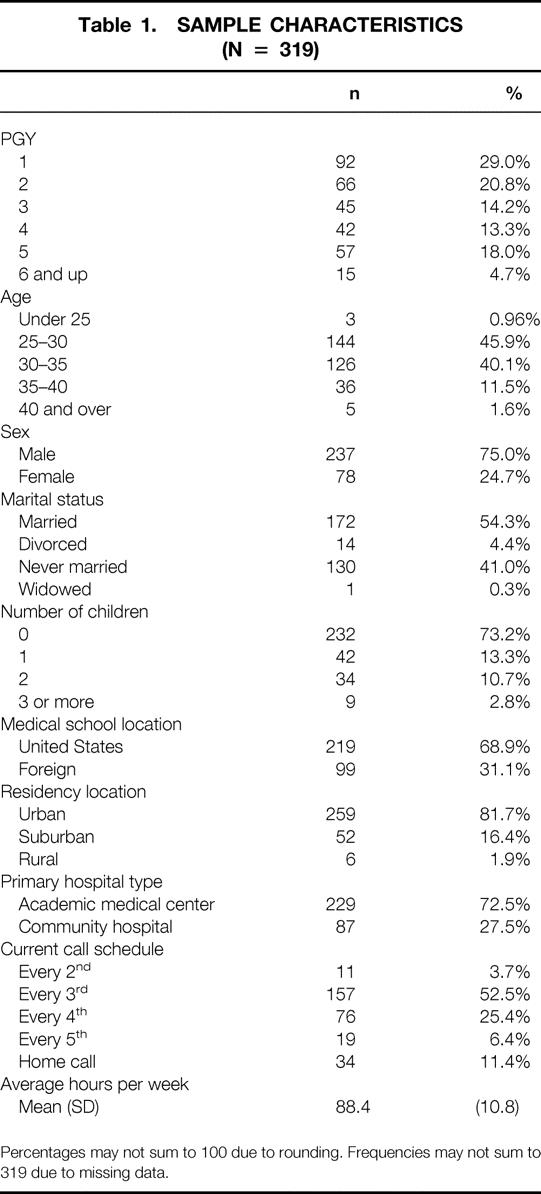

Of the 1,037 surveys mailed, 319 responses were received and 8 surveys were undeliverable, yielding an adjusted response rate of 31.0% (unadjusted rate 30.8%). The sample was evenly split between junior residents (postgraduate year [PGY] 1 and 2) and senior residents (PGY 3 and higher) (Table 1). Twenty-five percent of respondents were female, 1% were under 25 years old, 46% were age 25 to 30 years, and 53% were age 30 or older. Fifty-four percent of respondents were married and 27% had one or more children. Sixty-nine percent of respondents had attended a U.S. medical school, whereas 31% were foreign medical graduates. Eighty-two percent were training in a residency program located in an urban area. Seventy-three percent were training at an academic medical center, whereas 27% were at a community hospital.

Table 1. SAMPLE CHARACTERISTICS (N = 319)

Percentages may not sum to 100 due to rounding. Frequencies may not sum to 319 due to missing data.

Compliance With 405 Regulations

Eighty percent of surgical residents reported that the 405 Regulations are now “generally enforced” or “strictly enforced” in their residency program, and approximately three quarters of respondents reported that their surgical department is supportive of the Regulations. Reported duty hours generally corroborate the programs’ reported compliance with 405 Regulations, though the mean number of weekly hours worked in the hospital in the past year (88.4 hours) exceeded 80 hours and there was considerable variation in work hours (SD = 10.8, minimum 60 hours, maximum 140 hours). No statistically significant differences with respect to PGY level (junior vs. senior) or training environment (academic medical center vs. community hospital) were evident for the mean number of duty hours.

Similarly, most respondents reported call schedules that comply with 405 Regulations; less than 4% of respondents reported being on call in the hospital more often than every third night. Home call was more frequently reported by senior residents than by junior residents (16.7% vs. 5.4%, P < .05) and by those from academic medical centers versus those from community hospitals (14.3% vs. 4.7%, P < .05).

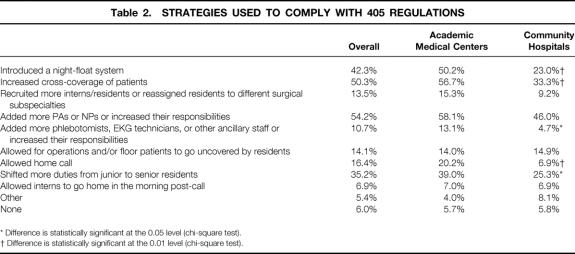

Eighty-three percent of respondents reported that enforcement of 405 Regulations has become stricter since they began their residency. While most (62%) reported that enforcement has gradually been getting stricter over time, 25% said that enforcement became much stricter after the hospital was fined, and 19% said that stricter enforcement was triggered by a major adverse patient outcome, a visit by the state or an accrediting agency, or some other event. Programs have adopted a range of strategies for complying with 405 Regulations; the most common are the use of night floats (42%), increased cross-coverage of patients (50%), and increased reliance on nurse practitioners and physician assistants (54%) (Table 2).

Table 2. STRATEGIES USED TO COMPLY WITH 405 REGULATIONS

* Difference is statistically significant at the 0.05 level (chi-square test).

† Difference is statistically significant at the 0.01 level (chi-square test).

Impacts on Residents and Patients

Seventy-three percent of participants “somewhat agreed” or “strongly agreed” that “All things considered, the work hours regulations are a good thing.” A greater percentage of juniors than seniors (86.7% vs. 59.5%, P < .05) expressed this view. This overall support, however, masks substantial ambivalence about the impact of the Regulations on residents and patients.

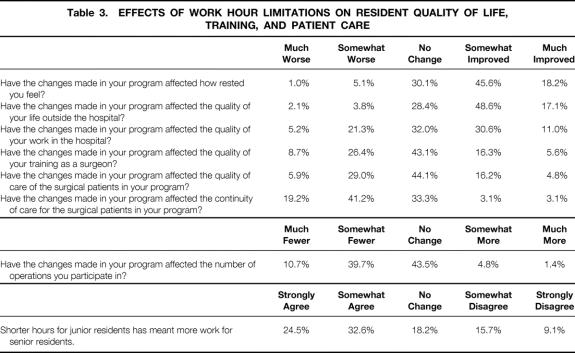

Resident Quality of Life

Improvements in how well-rested residents felt, residents’ quality of life outside the hospital, and their quality of work life in the hospital were reported by 64%, 66%, and 42% of respondents, respectively (Table 3). Seventy-one percent of respondents reported that they worked fewer hours because of the 405 Regulations, 25% reported no change, and 5% reported that they spent more hours in the hospital. A greater percentage of participants from community hospitals than from academic medical centers (81.0% vs. 66.4%, P < .05) reported a reduction in the number of hours spent in the hospital.

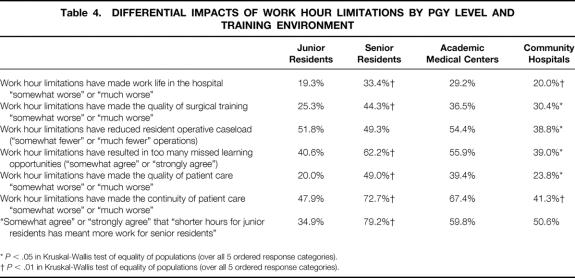

Table 3. EFFECTS OF WORK HOUR LIMITATIONS ON RESIDENT QUALITY OF LIFE, TRAINING, AND PATIENT CARE

A negative impact of the work hour limitations on the quality of residents’ work life was reported by a significantly greater percentage of senior residents than junior residents (33.4% vs. 19.3%, P < .01) and by a greater percentage of residents from academic medical centers than from community hospitals (28.2% vs. 20.0%, P < .01) (Table 4). Senior residents were also more likely than junior residents to report that the changes made in their program have resulted in the transfer of work from junior to senior residents (79.2% vs. 34.9%, P < .01).

Table 4. DIFFERENTIAL IMPACTS OF WORK HOUR LIMITATIONS BY PGY LEVEL AND TRAINING ENVIRONMENT

*P < .05 in Kruskal-Wallis test of equality of populations (over all 5 ordered response categories).

†P < .01 in Kruskal-Wallis test of equality of populations (over all 5 ordered response categories).

Thirty-five percent of respondents reported that the work hour limitations have hurt the quality of resident surgical training, whereas only 22% of participants reported that the changes have improved the quality of training. Although 47% of respondents reported that the changes have allowed for an increase in time for studying or reading, 50% of respondents reported a reduction in the number of operations in which they participate. Furthermore, 51% of respondents reported that the changes have resulted in residents “missing too many learning opportunities,” while 20% disagreed with this statement. Senior residents and residents at academic medical centers were significantly more likely than junior residents and residents at community hospitals to feel that the Regulations result in lost opportunities for learning and that this loss adversely affects training.

Quality of Patient Care

Residents had mixed views of the impacts of work hour regulations on surgical patient care. Thirty-five percent reported that the Regulations have harmed the quality of patient care, while 21% of respondents reported they have improved quality of care and 44% reported no change. With respect to continuity of care, 60% of respondents reported a negative impact, whereas 6% saw an improvement and the remainder saw no change.

Negative impacts of work hour limitations on the quality and continuity of care were reported by a significantly greater percentage of senior residents than junior residents and by a significantly greater percentage of residents from academic medical centers than from community hospitals. Indeed, decreased quality and continuity of care were reported by half and three quarters, respectively, of senior residents.

Ideal Duty Hours

When asked to suggest the number of hours that surgical residents should ideally spend in the hospital per week, the participants indicated a mean of 84.3 ± 12.3 hours. Over three quarters of participants “somewhat disagreed” or “strongly disagreed” with the statement, “I would be willing to add a year to my residency if it meant I could work shorter hours.” Only 15% of participants “somewhat agreed” or “strongly agreed” with this statement. A smaller percentage of senior residents than junior residents (8.8% vs. 20.9%, P < .05) were willing to countenance a longer residency.

DISCUSSION

Our findings suggest that implementation of work hour limitations, although generally accepted by surgical residents, may have negative consequences for patient care and resident education. New York surgical residents reported that their residency programs were in general compliance with the 405 Regulations, and these reports were broadly corroborated by residents’ reported duty hours and call schedules. However, the survey responses suggest that surgical residents who have experienced the implementation of duty hour restrictions are deeply ambivalent about the impacts of such restrictions on patient care and resident training. Whereas three quarters of residents felt that overall the Regulations were a good thing, effecting improvements in residents’ quality of life, a substantial proportion reported negative impacts on surgical training and quality and continuity of care. Negative perceptions of the impact of the duty hour restrictions were particularly prevalent among senior residents and residents training at academic medical centers.

An important finding of our study is that senior surgical residents had significantly more negative perceptions of the 405 Regulations than interns and PGY2 residents. Several factors may account for this disparity. First, 79% of senior residents reported that their programs had coped with duty hour restrictions by shifting work previously performed by junior residents to seniors. Traditionally in surgery residencies, “scut” work is concentrated in the junior years, with the senior years featuring more operative experience. Although some “scut” may have educational value for junior residents, it is unlikely to have any value for senior residents. Shifting this work and other duties to senior residents understandably engenders resentment. As one senior resident commented, “Junior residents go home postcall. There is no money for more help, so senior residents cover more ‘scut’ work, which keeps us in the hospital long hours. There is less continuity of care and everyone’s experience is adversely affected.”

Second, the senior residents in our sample experienced the work environment before strict enforcement of the 405 Regulations. They thus may feel doubly victimized by the system: they worked long hours as junior residents, and just when they expected their workload to abate, they were forced to shoulder additional work so that new cohorts of junior residents could have shorter work weeks.

Third, senior residents have trained longer in surgery and therefore may have internalized the culture of surgery (with its strong emphasis on commitment to patients and continuity of care) to a greater extent than junior residents, influencing their perceptions of 405-related changes. For example, one senior resident remarked, “The ethic of being a doctor and a surgeon has been systematically destroyed”; another felt that the Regulations “have created a group of interns/junior residents who have less skills as physicians, tire easily, and are not committed to caring for patients if it conflicts with their work hours.” In contrast, a typical comment from a junior resident is as follows: “Definitely a good idea. We are human beings, not just warm bodies able to follow instructions. Hours and working conditions are much more humanized, and patient care has not been compromised as a result.”

Finally, our junior resident sample consisted not only of categorical general surgery residents, but also preliminary residents destined for further training in surgical subspecialties or even nonsurgical fields. Their input may have skewed the results in ways that defy prediction.

Our findings also suggest that patient care and resident education are harmed by work hour limitations to a greater extent in academic health centers than in community hospitals. Whether differences in compliance strategies, patient acuity, or other factors account for this finding will require further study.

Several prior surveys of surgical and other residents have found that a strong majority of residents support duty hour regulations in principle. 12–16 However, few studies have reported on the perceptions and attitudes of surgical residents who have actually experienced work hour regulations. A report from a surgical residency program in California that voluntarily adopted a 72-hour work week for residents found that actual duty hours remained significantly above the limit, but that surgical residents had higher work satisfaction than other residents. 17

Previous reports of the impact of the 405 Regulations in New York are limited to single-institution surveys conducted in the early 1990s, before compliance became widespread. None examined the implementation of the regulations in general surgery residency programs. A survey of senior residents in two internal medicine programs conducted in 1991 at a single New York institution suggested that residents’ views of the Regulations were generally positive, with good agreement that the Regulations decreased their fatigue and made residency more manageable, but less strong agreement that they had positive impacts on patient care. 18 A qualitative study of 21 internal medicine interns at a New York hospital in 1993 found that residents were very supportive of the work hour regulations, citing benefits for resident learning and quality of care and downplaying problems with continuity of care. 15 A survey of residents in an obstetrics and gynecology residency program suggested that implementation of the 405 Regulations was associated with improvements in quality of resident life but decrements in continuity of patient care. 19

Other reports of the impacts of the 405 Regulations have drawn on surveys of hospital executives 20 and analysis of hospital discharge records. A retrospective cohort study of patients discharged from the internal medicine service of a New York hospital before and after the implementation of the Regulations found that restricted resident work hours were associated with delayed test ordering and higher rates of in-hospital complications. 21

Our study findings are broadly consistent with those of previous surveys but suggest that general surgery residents take a more critical view of the impact of work hour limitations on patient care and resident education than residents in other specialties. Our findings also build on previous studies by identifying a schism between the attitudes of junior and senior residents.

The strengths of our study include the rigorously developed survey instrument and its statewide administration to surgical residents, a group whose input has been underrepresented in the dialog on resident work hours. An important limitation of our study is its somewhat low response rate (31%) despite three mailed follow-up contacts. Low response rates are common in resident surveys 16,22–24 due to the demanding schedules of residents and the frequency with which they are surveyed. New York residents in particular may be experiencing “survey fatigue” due to repeated polling. In addition, our ability to conduct aggressive follow-up with nonresponders was limited by our desire to preserve the strict responder anonymity necessary for ensuring honest responses.

To detect possible nonresponse bias, we compared survey nonrespondents and respondents on demographic characteristics for which data were available. No significant differences between respondents and nonrespondents were observed in chi-square tests for sex, residency program location (urban/suburban/rural), or primary hospital type (academic medical center/community). However, senior residents were significantly more likely than junior residents to respond to the survey (34% vs. 27%, P < .01), due primarily to low (25%) response by interns. Ten of those who returned the survey questionnaire failed to return tracking postcards and thus were classified as nonrespondents in this analysis.

Nationwide implementation of resident work hour limitations is imminent. Compliance with the ACGME requirements will require significant changes in most general surgery residency programs, in which work hours approaching 110 hours per week are common (Whang EE, Perez A, Ashley SW, et al. A contemporary survey of all general surgery residents in New England. Unpublished manuscript, 2002). Our findings highlight several pitfalls associated with the implementation of resident work hour limitations in general surgery residency programs. We must anticipate these problems and be prepared to deal with them as we develop implementation strategies for the ACGME requirements in our programs.

First, we must ensure that quality of patient care is not jeopardized. The relationship between quality of care and continuity of care has been well documented and, indeed, serves as the basis for one of the most fundamental ethical principles of our profession: commitment to the total care of our patients. 25 The shift-type work schedules implicit in the ACGME requirements entail frequent “hand-offs” among caregivers, a phenomenon that recent research at our institution has identified as having an etiologic role in the commission of medical errors. 26 System strategies such as standardized or even computerized “sign-outs” and multiple levels of redundancy in patient care will need to be implemented to prevent decrements in quality of care related to loss of continuity of care.

Second, we must ensure that surgical resident education is not jeopardized. Reductions in operative caseloads and exposure to challenging clinical problems are only part of the problem. Perhaps more importantly, our ability to impart to residents a sense of responsibility to our patients, our work, and our profession may be undermined. Clearly, we must increase the efficiency of resident education, given the reduction in the total amount of time available. We must strive to minimize the tasks that serve no educational or clinical value that occupy so much of our residents’ workday. Adding other healthcare professionals to our teams is likely to be the best strategy for accomplishing this goal, though it will entail considerable costs.

Third, we must ensure that our senior surgical residents do not become the last line of defense in a system that moves to restricted duty hours for junior residents. Senior residents need to have responsibilities and educational experiences that are appropriate to their level of training. The strategy of shifting “scut” work to senior residents is short-sighted and must be avoided.

Lastly, we must avoid being complacent. Even after implementation of work hour limitations, we must continue to strive to improve the work environment and educational experience of our residents. The declining interest in surgical careers among medical students, highlighted by the increasing number of unfilled general surgery PGY1 positions in recent years’ matches, only contributes to the urgency of achieving these goals. 25 It is time for us to study the state of our profession and to plan its future before someone else does it for us.

Footnotes

Supported by general institutional funds from the Brigham and Women’s Hospital Department of Surgery.

Correspondence: Michael J. Zinner, MD, Department of Surgery, Brigham & Women’s Hospital, 75 Francis Street, Boston, MA 02115.

E-mail: mzinner@partners.org

Accepted for publication November 25, 2002.

References

- 1.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Report of the ACGME Work Group on Resident Duty Hours [Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education web site]. June 11, 2002. Available at: http://www.acgme.org/new/wkgreport602.pdf. Accessed August 12, 2002.

- 2.N.Y. Comp. Codes R, Regs. title 10, §405.4 (2002).

- 3.Asch DA, Parker RM. The Libby Zion case: one step forward or two steps backward? N Engl J Med. 1988; 318: 771–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wallack MK, Chao L. Resident work hours: the evolution of a revolution. Arch Surg. 2001; 136: 1426–1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Philibert I, Friedmann P, Williams WT. New requirements for resident duty hours. JAMA. 2002; 288: 1112–1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Green M. For Whom the “Bell” Tolls: How Hospitals Violate the “Bell” Regulations Governing Resident Working Conditions. New York: Office of the Public Advocate for the City of New York, 1994.

- 7.Green M. Putting Patients at Risk: How Hospitals Still Violate the “Bell” Regulations Governing Resident Working Conditions. New York: Office of the Public Advocate for the City of New York, 1997.

- 8.DeBuono BA, Osten WM. The medical resident workload: the case of New York State. JAMA. 1998; 280: 1882–1883. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCall T. The impact of long working hours on resident physicians. N Engl J Med. 1988; 318: 775–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.New York State Department of Health Ad Hoc Advisory Committee on Emergency Services. Supervision and Residents’ Working Conditions. New York: Department of Health, 1987.

- 11.Green MJ. What (if anything) is wrong with residency overwork? Ann Intern Med. 1995; 123: 512–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruby ST, Allen L, Fielding LP, et al. Survey of residents’ attitudes toward reform of work hours. Arch Surg. 1990; 125: 764–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strunk CL, Bailey BJ, Scott BA, et al. Resident work hours and working environment in otolaryngology. Analysis of daily activity and resident perception. JAMA. 1991; 266: 1371–1374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Defoe DM, Power ML, Holzman GB, et al. Long hours and little sleep: work schedules of residents in obstetrics and gynecology. Obstet Gynecol. 2001; 97: 1015–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yedidia MJ, Lipkin M Jr, Schwartz MD, et al. Doctors as workers: work-hour regulations and interns’ perceptions of responsibility, quality of care, and training. J Gen Intern Med. 1993; 8: 429–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng TL. House staff work hours and moonlighting: what do residents want? A survey of pediatric residents in California. Am J Dis Child. 1991; 145: 1104–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schwartz RI, Dubrow TJ, Rosso RF, et al. Guidelines for surgical residents’ working hours: intent vs. reality. Arch Surg. 1992; 127: 778–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Conigliaro J, Frishman WH, Lazar EJ, et al. Internal medicine housestaff and attending physician perceptions of the impact of the New York State section 405 regulations on working conditions and supervision of residents in two training program. J Gen Intern Med. 1993; 8: 502–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kelly A, Marks F, Westhoff C, et al. The effect of the New York State restrictions on resident work hours. Obstet Gynecol. 1991; 78: 468–473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thorpe KE. House staff supervision and working hours: implications of regulatory change in New York State. JAMA. 1990; 263: 3177–3181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laine C, Goldman L, Soukup JR, et al. The impact of a regulation restricting medical house staff working hours on the quality of patient care. JAMA. 1993; 269: 374–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li J, Tabor R, Martinez M. Survey of moonlighting practices and work requirements of emergency medicine residents. Am J Emerg Med. 200; 18: 147–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lawler LP, Fromke J, Evens RG. Results of and comments on the 2000 survey of the American Association of Academic Chief Residents in Radiology. Acad Radiol. 2001; 8: 777–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Wagenen FK, Weidman ER, Duncan JR, et al. Results of the 1996 survey of the American Association of Academic Chief Residents in Radiology. Acad Radiol. 1997; 4: 132–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zinner MJ. Surgical residencies: Are we still attracting the best and the brightest? Bull Am Coll Surg. 2002; 87: 20–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peterson LA, Brennan TA, O’Neil AC, et al. Does housestaff discontinuity of care increase the risk for preventable adverse events? Ann Intern Med. 1994; 121: 866–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]