Abstract

Objective

To compare patient outcome following repair of a primary groin hernia under local (LA) or general anesthesia (GA) in a randomized clinical trial.

Summary Background Data

LA hernia repair is thought to be safer for patients, causes less postoperative pain, cost less, and is associated with a more rapid recovery when compared with the same operation performed under GA.

Methods

All patients presenting to three surgeons during the study period with a primary groin hernia were considered eligible. Outcome parameters measured including tests of vigilance, divided attention, sustained attention, memory, cognitive function, pain, return to normal activity, and costs.

Results

Two hundred seventy-nine patients were randomized to LA or GA hernia repair; 276 of these had an operation, with 138 participants in each group. At 6, 24, and 72 hours postoperatively there were no differences in vigilance or divided attention between the groups. Similarly, memory, sustained attention, and cognitive function were not impaired in either group. Although physical activity was significantly impaired at 24 hours, this and return to usual social activities were similar in both groups. While patients in the LA group had significantly less pain on moving, at 6 hours they were less likely to recommend the same operation to someone else. GA hernia repair cost 4% more than the same operation under LA.

Conclusions

There are no major differences in patient recovery after LA or GA hernia repair. Patients should be offered a choice of anesthesia, LA or GA, for repair of their groin hernia.

There has been a renewed interest in the use of local anesthesia (LA) for inguinal hernia repair. This has been brought about by the rapid introduction of tension-free hernioplasty, which is thought to be easier to perform than conventional methods of hernia repair. 1 The advantages claimed for the use of LA include increased safety for patients, better postoperative pain control, shorter recovery period, and reduced cost when compared with hernia repair performed under general anesthesia (GA).

It is not possible to assess differences in safety between LA and GA hernia repair as mortality and serious cardiovascular events are so low following this procedure. 2 GA, however, has been thought to have a significant effect on psychomotor skills, attention, and memory in the postanesthesia period. Some authors have suggested this effect may be long term and related to cerebral ischemia. 3 This is thought to be particularly the case in elderly patients with significant comorbid disease. Given that local anesthetics have little or no serious CNS effects, one might anticipate that their use would be associated with better outcomes in terms of cognitive function.

We report a randomized clinical trial comparing LA and GA open hernia repair.

METHODS

Three surgeons from three hospitals in Scotland took part in this trial, which was approved by the relevant local research ethics committees. Patients were recruited between January 1998 and October 2000. All patients with a groin hernia were eligible unless they had a recurrent or irreducible inguinoscrotal hernia or presented as an emergency. Patients were randomized by a central telephone service run by the Trial Coordinating Center in the Robertson Center for Biostatistics, University of Glasgow, after stratification by a consultant surgeon.

Surgical Procedures

All patients with a primary inguinal hernia had an open tension-free hernioplasty. 1 Patients with a femoral hernia had a nonmesh repair using a low approach.

Anesthesia

All patients received premedication 1 to 2 hours before surgery (temazepam 30 mg, metoclopramide 10 mg, diclofenac sodium [Voltarol SR] 75 mg) unless contraindicated. Patients randomized to the LA group received their anesthesia similar to that described by Amid et al., 1 except that 1% lidocaine with adrenaline (1:200,000) was used instead of a mixture of lidocaine and bupivacaine. Patients who required sedation or analgesia during surgery were given 1-mL intravenous increments of a mixture containing midazolam (1 mg/mL) and fentanyl (10 mcg/mL) intravenously. Patients randomized into the GA group were induced with propofol 2 mg/kg and fentanyl 1 mcg/kg. They were then allowed to breathe spontaneously a mixture of 60% nitrous oxide in oxygen with isoflurane 1% to 1.5% through a laryngeal mask. All groups received infiltration of bupivacaine 0.25% into the surgical wounds for postoperative analgesia. They were also prescribed diclofenac sodium twice daily (Voltarol SR 75 mg) unless contraindicated and Coproxamol two tablets every 4 hours as required (maximum 8 tablets per 24 hours) for the duration of their hospital stay. Patients who experienced pain in the recovery room were allowed intravenous increments of morphine 1 to 2 mg as required every 5 minutes until comfortable. A record of analgesia use in the postoperative period was maintained for both groups of patients; all completed visual analog pain scores at rest and on moving preoperatively and 6, 24, and 72 hours postoperatively.

Assessment of Recovery

Psychomotor recovery was assessed using tasks with known sensitivity to the effects of anesthetic and other sedative drugs. Sustained attention was assessed by a 2-minute dual task 4 requiring the patient to divide attention between a tracking task (using a joystick to pursue a target on a VDU, the score being that of time-on-target) while simultaneously responding as rapidly as possible by button press to unpredictable visual signals in the periphery of the VDU (reaction time scored in milliseconds). Dual-task performance shows sensitivity to postanesthetic impairment and sedation. 5,6 Attention was assessed with the Digit-Symbol-Substitution Task (DSST), which requires the patient to carry out a coding task where nonsense symbols must be substituted for digits. The task has sensitivity to age-related differences in postanesthetic impairment. 7 Vigilance was assessed by a 2-minute task requiring the patient to detect consecutive occurrences of a three-digit number in a rapidly presented series of such numbers on a VDU. 4 The task is sensitive to subtle residual effects of general anesthetic agents. 8

Memory was assessed with the Logical Memory test from the Wechsler Memory Scale. Subjective impairment was assessed with the Cognitive Failures Questionnaire (CFQ) 9 concerning everyday failures of memory, attention, and co-ordination; this has been shown to be differentially sensitive to LA versus GA. 10

The tasks were performed preoperatively to permit practice and to derive a baseline measure and then at 6, 24, and 72 hours postoperatively to coincide with the outpatient visit. The Logical Memory test and DSST were performed preoperatively and at 3 days only. The CFQ was completed preoperatively and at 3 and 6 days, the latter being in the patient’s home.

Reaction time was assessed as part of the dual task described above and also by a simple “driving simulator” that measured the time taken for patients to lift their foot from an accelerator pedal and press a brake pedal on the appearance of a red image on a VDU. 11 Patients were also asked to get up from their bed and walk a standard distance before returning to bed to assess physical activity before and after surgery. Both tests were performed preoperatively and 24 hours postoperatively. Patients in both groups also completed an SF-36 3 months postoperatively to assess return to normal activity and satisfaction with their operation. 12

Patients were reviewed as surgical outpatients 1 year after their operation. At this visit all tests of psychomotor response and memory were repeated. In addition, patients were asked to complete a visual analog pain score at rest and movement, and the hernia site was examined for any evidence of recurrence or other chronic complication.

Economics

A data collection form recording all aspects of hospital resources was designed, piloted, and previously used in a randomized trial evaluating laparoscopic hernia repair. 13 This included data on operating room and staff costs, costs of hospital stay, and other healthcare costs, including costs of complications such as wound hematoma or infection.

Statistics

Data were analyzed by intention to treat. Within- and between-group differences were analyzed using paired and two-sample t tests, respectively. Where there was sufficient doubt about the validity of parametric assumptions, a Wilcoxon or Mann-Whitney test was performed. Categorical data were analyzed using the chi-square test (or Fisher exact test in the case of few observations). A significance level of 5% was used throughout, and no adjustment was made for multiple comparisons.

This trial was initiated as a three-arm trial that included a laparoscopic group repaired under GA. Based on a previous nonrandomized study, 10 a sample size of 600 patients (i.e., 200 per group) would have been required to complete this study. However, after reviewing recruitment in the first year of the trial, it became apparent that we would not be able to achieve this target. In consultation with our statistician, local ethics committee, and the grant awarding body, it was agreed that the trial should proceed as a two-arm trial comparing LA with GA anesthetic open hernia repair so as to achieve an answer to the primary aim of the study (the effect of anesthesia on patient recovery). A total sample size of 300 patients (i.e., 150 per group) was calculated for the two-arm study. A study of this size has an 80% power to detect a difference of 33% of the standard deviation at a significance level of 5%.

RESULTS

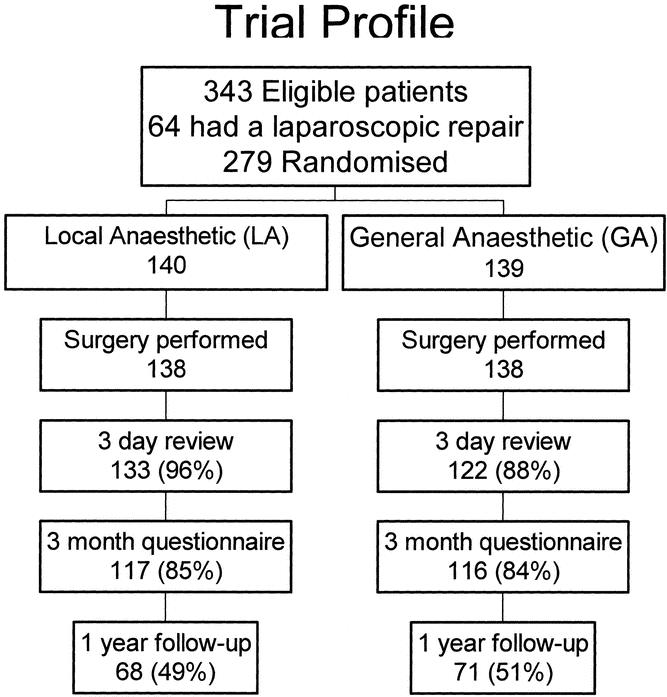

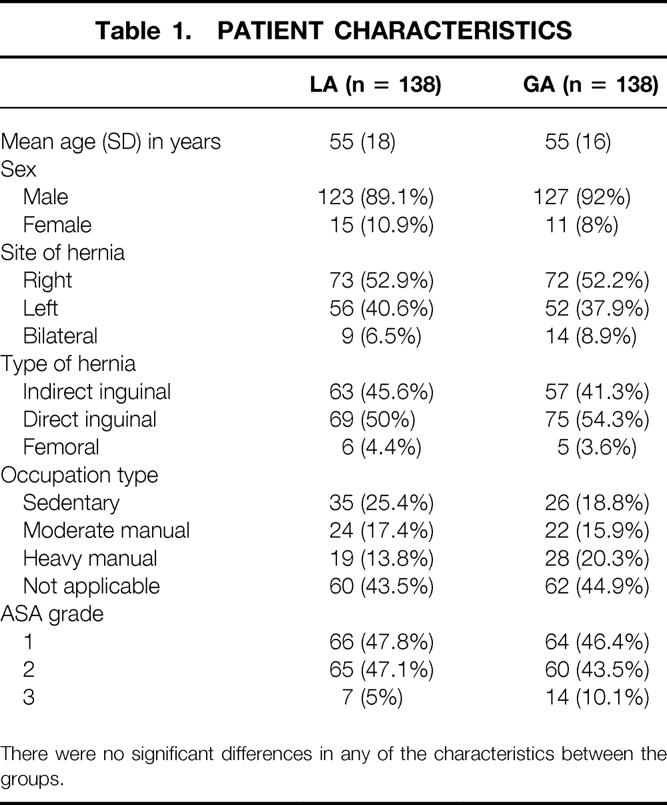

The trial identified 343 eligible patients, of whom 279 gave their consent to be randomized to LA or GA open hernia repair (Fig. 1). Three patients (two in the LA group and one in the GA group) did not have an operation: their hernia repair was cancelled due to the discovery of a significant serious comorbid illness after randomization. Four patients in each group did not receive the treatment allocated; in the LA group, four patients changed their mind in the anesthetic room and requested a general anesthetic, and four patients in the GA group received a local anesthetic because an anesthetist was not available. Patient characteristics in both groups were similar at trial entry (Table 1).

Figure 1. Trial profile.

Table 1. PATIENT CHARACTERISTICS

There were no significant differences in any of the characteristics between the groups.

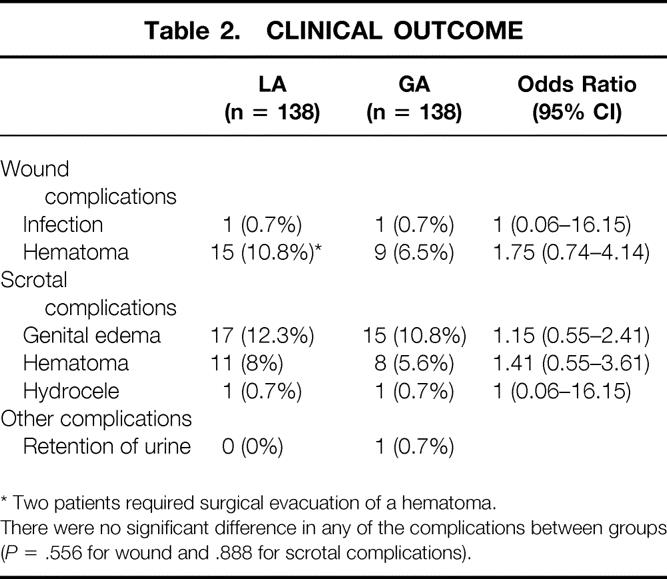

There was no difference in the grade of the operator in either group. A consultant performed 27% of hernia repairs in either group, while a surgical trainee performed 73% supervised by a consultant. One operative complication, a bladder injury, occurred in the GA group; it was recognized and repaired. One patient in the GA group had to be returned to the operating room for a postoperative bleed from the wound edge. Postoperative complications were similar in both groups (Table 2).

Table 2. CLINICAL OUTCOME

* Two patients required surgical evacuation of a hematoma.

There were no significant difference in any of the complications between groups (P = .556 for wound and .888 for scrotal complications).

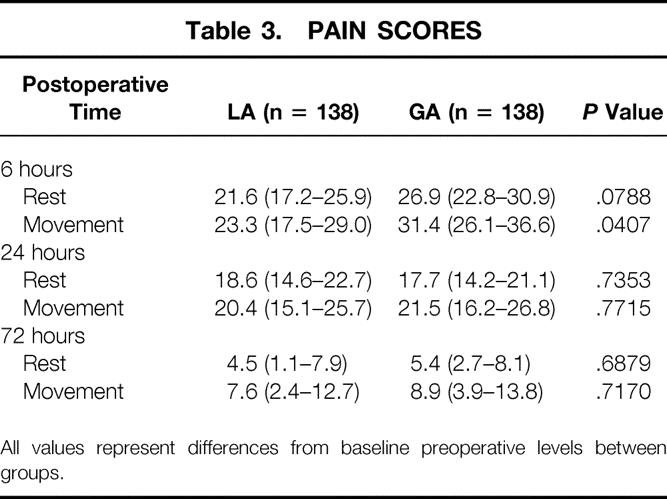

Pain and Analgesia

Patients in the LA group had significantly less pain on movement at 6 hours postoperatively (Table 3). This effect was transient, however, and had disappeared at 24 and 72 hours. Ninety-two patients (66.6%) in the LA group required morphine in the recovery room, compared with 105 (76%) in the GA group (P = .070) Ninety-five percent of patients in the LA group required oral analgesia on discharge, compared with 97.6% in the GA group (P = .336). At day 3, the respective percentages still using analgesia were 76% and 82% (P = .274).

Table 3. PAIN SCORES

All values represent differences from baseline preoperative levels between groups.

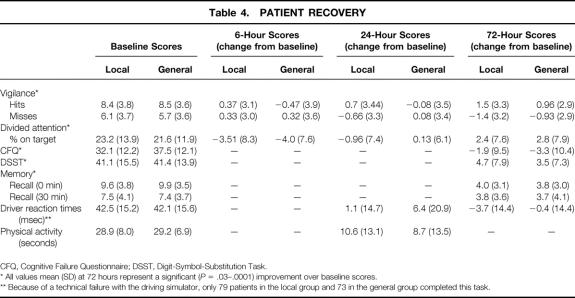

Patient Recovery

There were no significant differences between the groups in any of the recovery parameters measured (Table 4). Computerized tests of vigilance and divided attention demonstrated no significant impairment in either group at 6, 24, or 72 hours postoperatively. Likewise, there was no impairment of memory at 3 days or cognitive failure at 3 and 6 days postoperatively. The performance of both groups did, however, improve significantly from the preoperative baseline to the 72-hour follow-up. Although physical activity was significantly reduced (P = .0001) at 24 hours postoperatively in both groups, driver reaction times were not significantly changed from preoperative levels.

Table 4. PATIENT RECOVERY

CFQ, Cognitive Failure Questionnaire; DSST, Digit-Symbol-Substitution Task.

* All values mean (SD) at 72 hours represent a significant (P = .03–.0001) improvement over baseline scores.

** Because of a technical failure with the driving simulator, only 79 patients in the local group and 73 in the general group completed this task.

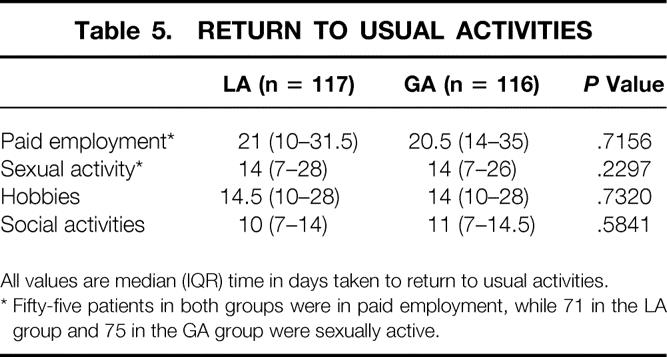

Return to Normal Activity and Patient Satisfaction

Patients in both groups took an average of 2 weeks to return to their normal activities; return to work required an additional week (Table 5). When asked if they would recommend the same hernia operation to someone else, significantly fewer patients in the LA group (84% vs. 95% [P = .011]) said they would recommend it. Patient satisfaction with the hernia scar was similar in both groups.

Table 5. RETURN TO USUAL ACTIVITIES

All values are median (IQR) time in days taken to return to usual activities.

* Fifty-five patients in both groups were in paid employment, while 71 in the LA group and 75 in the GA group were sexually active.

Economics

There were no differences in operative time (LA 37.5 ± 9.4 minutes, GA 34.2 ± 10.4 minutes, P = .185) or total anesthetic time (LA 48.4 ± 9.7 minutes, GA 48.8 ± 10.4 minutes, P = .868) between the groups. Similarly, total hospital stay was 3.1 ± 0.8 days for the LA group and 3.2 ± 1.2 for the GA group. The only cost differences between groups, therefore, amounted to the resources associated with use of a GA, which cost £30.54 per case. This represented 4% of the total hospital cost of a GA hernia repair.

Outcome at 1 Year

Around 50% of the patients returned at 1 year to complete tests of vigilance, divided attention, sustained attention, memory, cognitive failure, and pain. There was no significant impairment or difference between the groups in memory or psychomotor response. Compared with baseline values, patients in both groups had significantly less pain on movement but not at rest 1 year after their hernia repair. This amounted to a reduction in pain scores on movement from 16.6 ± 22.2 preoperatively to 8.8 ± 14.7 at 1 year (P = .0176) in the LA group and from 17.0 ± 22.5 to 6.2 ± 9.6 (P = .0003) in the GA group. No patient had clinical evidence of a recurrence of hernia.

DISCUSSION

In the United Kingdom, LA is rarely used for hernia repair. 2 This is in contrast to other countries and hernia centers, where it is the preferred form of anesthesia for this operation. This study shows that GA causes no significant impairment of cognitive function, memory, psychomotor response, or return to normal activity in those undergoing hernia repair. Patients were assessed using a wide variety of tests, including computerized tests of attention and vigilance, the Logical Memory test from the Wechsler scale, the DSST, and questionnaires of cognitive function and return to normal activities. The only significant impairment in any parameter in this study was, as might be expected, in physical activity. The degree of impairment was similar in both groups, although the GA group had more pain on moving at 6 hours postoperatively.

There have been no large randomized clinical trials comparing LA and GA for hernia repair. Prospective comparisons, however, between both types of anesthesia show a consistent pattern of reduced pain after LA. 14–18 The effect appears greater than in this study and probably reflects the fact that most were nonrandomized studies. Another important factor may be that patients in both groups in our study received infiltration of bupivacaine 0.25% into their wound for postoperative analgesia. A third factor may be that most operations in previous studies were sutured repairs under tension compared with tension-free repair in our study, which is thought to be less painful. In general, no other differences have been found after LA or GA hernia repair, apart from one study 16 showing a significant increase in urinary retention at 12.4% after GA. The incidence of this complication was higher than expected and compares with an incidence of less than 1% in our study.

A number of trials have compared regional with general anesthesia in patients undergoing other operative procedures. In a randomized trial of 262 patients undergoing knee replacement, Williams-Russo et al. 3 were unable to demonstrate any significant differences between epidural and general anesthesia on any of 10 cognitive tests at either 1 week or 6 months. A similar study by Jones et al. 19 in patients undergoing hip and knee replacement was unable to demonstrate any impairment in cognitive and functional competence in those randomized to spinal or general anesthesia. However, in a prospective nonrandomized study in patients undergoing a variety of surgical procedures under GA or LA by Tzabar et al., 10 the GA group had a significantly higher incidence of cognitive failures at 3 days postoperatively. This effect had disappeared at 6 days, and it is possible that the differences observed at 3 days reflected the fact that the GA group had undergone more invasive operative procedures than their LA counterparts.

Clear interpretation is, however, confounded by the fact that the two groups differed in age. In the present study, the fact that performance improved significantly from the preoperative state to the 72-hour follow-up is probable evidence of a gross practice effect. Such an effect may mask the occurrence of impairment, particularly where only a proportion of patients are impaired so that they contribute only a small effect to the group mean performance. 6 It may be, therefore, that evidence of minor impairment may have gone undetected in the present study.

One of the surprising findings of this study was that significantly fewer patients in the LA group would recommend the same operation to someone else. This occurred despite the fact that patients in both groups all received premedication and did not know what arm they were randomized to until in the anesthetic room. Given that there were no significant differences in satisfaction with their wounds or other postoperative problems, it is likely that recall of what happened during surgery may have influenced their response.

Mortality after elective hernia surgery is sufficiently low that it is not possible to assess differences using either LA or GA in a clinical trial setting. In the Swedish Hernia Register, mortality after elective hernia repair was lower than the standardized 30-day mortality for the population as a whole. 20 This occurred despite the fact that only 2% of patients had LA repair in that country in 1996. Claims, therefore, that one type of anesthesia is safer than another are unfounded and should not influence decision making in the medically fit patient with a groin hernia.

There were few differences in costs between LA and GA hernia repair in this study. Costs were high in this study because all operations took place in an operating room that routinely undertakes major surgery, so capital and staff costs are greater than in a dedicated hernia or day-case center. In addition, all operations were performed on an inpatient basis. The greatest savings in costs for hernia repair are to be made by increasing the number of day-case operations. In Scotland, an audit of hernia repairs in 1998 revealed that only 25% of patients had day-case hernia surgery. 2 For those who require inpatient hernia repair for reasons of age or serious comorbid illness, indirect cost savings can be made by scheduling an LA repair before a major surgery case. This allows the anesthetist time to prepare the major case in the anesthetic room and increases efficiency by reducing turnover time between cases.

One of the criticisms of this study could be the use of low dose intravenous Midazolam and Fentanyl in the local anesthetic group. Both have known effects on the central nervous and respiratory systems. However, these are of rapid onset and short duration following parenteral administration. 21,22 The short duration of action of Fentanyl is probably due to rapid redistribution into the tissues rather than metabolism and excretion. Its elimination half-life is about 4 hours whereas that of Midazolam is around 2 hours. This makes it unlikely that either agent would have had any significant effect on the results from the study given that tasks were performed at 6, 24 and 72 hours postoperatively.

This study demonstrates that there are no major differences in patient recovery after LA or GA hernia repair. Recovery is rapid after both type of anesthetics, with no short- or long-term effects on cognitive function or psychomotor response, and the decision to use one or the other should be at the discretion of the individual surgeon in consultation with the patient.

Footnotes

Funded by a grant from the Scottish Executive.

Correspondence: Prof. P. J. O’Dwyer, University Department of Surgery, Western Infirmary, Glasgow G211 6NT, Scotland, UK.

E-mail: p.j.odwyer@clinmed.gla.ac.uk

Accepted for publication September 27, 2002.

References

- 1.Amid PL, Shulman AG, Lichtenstein IL. Local anesthesia for inguinal hernia repair. Step-by-step procedure. Ann Surg. 1994; 220: 735–737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hair A, Duffy K, McLean J, et al. Hernia repair in Scotland. Br J Sur. 2000; 87: 1722–1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams-Russo P, Sharrock NE, Mattis S, et al. Cognitive effects after epidural vs. general anesthesia in older adults. A randomized trial. JAMA. 1995; 274: 44–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hope A, Woolman PS, Gray WM, et al. A system for psychomotor evaluation; design, implementation and practice effects in volunteers. Anaesthesia. 1998; 53: 545–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moss E, Hindmarch I, Pain AJ, et al. Comparison of recovery after halothane or alfentanil anaesthesia for minor surgery. Br J Anaesth. 1987; 59: 970–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Millar K. The effects of anaesthetic and analgesic drugs. In: Smith AP, Jones DM, eds. Handbook of human performance, Vol. 2. London: Academic Press, 1992; 337–385.

- 7.Chung F, Seyone C, Chung A, et al. Age-related cognitive recovery after general anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 1990; 71: 217–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wesnes KA, Simpson P, Christmas L. A microcomputerised system for evaluating the cognitive actions of drugs in the young, elderly and demented. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1989; 36: A38. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Broadbent DE, Cooper PF, Fitzgerald P, et al. The Cognitive Failures Questionnaire (CFQ) and its correlates. Br J Clin Psychol. 1982; 21: 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tzabar Y, Asbury AJ, Millar K. Cognitive failures after general anaesthesia for day-case surgery. Br J Anaesth. 1996; 76: 194–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wright DM, Hall MG, Patterson CR, et al. A randomised comparison of driver reaction time after open and endoscopic tension-free inguinal hernia repair. Surg Endosc. 1999; 13: 332–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The MRC Laparoscopic Groin Hernia Trial Group. Laparoscopic versus open repair of groin hernia: A randomised comparison. Lancet. 1999; 354: 185–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Medical Research Council Laparoscopic Groin Hernia Trial Group. Cost-utility analysis of open versus laparoscopic groin hernia repair: Results from a multicentre randomised clinical trial. Br J Surg. 2001; 88: 653–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teasdale C, McCrum A, Williams NB, et al. A randomised controlled trial to compare local with general anaesthesia for short-stay inguinal hernia repair. Ann Roy Coll Surg Eng. 1982; 64: 238–242. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Young DV. Comparison of local, spinal and general anesthesia for inguinal herniorrhaphy. Am J Surg. 1987; 153: 560–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peiper C, Töns C, Schippers E, et al. Local versus general anesthesia for Shouldice repair of the inguinal hernia. World J Surg. 1994; 18: 912–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Makuria T, Alexander-Williams J, Keighley MRB. Comparison between general and local anaesthesia for repair of groin hernias. Ann Roy Coll Surg Engl. 1979; 61: 291–294. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bernia R, Hashemi F, Stryker SJ, et al. A comparison of general versus local anesthesia during inguinal herniorrhaphy. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1992; 174: 277–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones MJT, Piggott SE, Vaughan RS, et al. Cognitive and functional competence after anaesthesia in patients aged over 60: Controlled trial of general and regional anaesthesia for elective hip or knee replacement. Br Med J. 1990; 300: 1683–1687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haapaniemi S, Sandblom G, Nilsson E. Mortality after elective and emergency surgery for inguinal and femoral hernia. Hernia. 1999; 4: 205–208. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mather LE. Clinical pharmacokinetics of fentanyl and its newer derivatives. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1983; 10: 422–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garzone PD, Kroboth PD. Pharmacokinetics of the newer benzodiazepines. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1989; 16: 337–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]