Abstract

Objective

To identify predictors of nonsentinel node (NSN) tumor involvement in patients with a tumor-involved sentinel node (SN).

Summary Background Data

For many breast cancer patients who undergo intraoperative lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymphadenectomy (LM/SL), the SN is the only tumor-involved axillary node. Associations between NSN tumor involvement and several clinical and histopathologic factors have been identified. The authors hypothesize that extracapsular extension (ECE) of the SN metastasis is highly predictive of NSN tumor involvement.

Methods

Between May 1998 and December 2001, 260 patients (263 cases) with clinical T1 or T2 (<5.0 cm) breast cancer underwent LM/SL at the University of North Carolina, using a combined blue dye and technetium sulfur colloid technique. In all cases with a tumor-involved SN, axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) was recommended. Statistical analysis, with Pearson chi-square tests, Fisher exact test, and multiple logistic regression, was performed.

Results

The SN contained tumor in 74 (28.1%) cases. ALND was performed in 70 of the 74 cases. ECE of the SN metastasis was present in 18 (25.7%) of the 70 cases. Patients with ECE of the SN metastasis were more likely to have NSN tumor involvement and had a greater total number of tumor-involved nodes than patients without ECE of the SN metastasis. Increasing size of the SN metastasis and increasing size of the primary tumor, examined as continuous variables, were associated with an increased likelihood of NSN tumor involvement on univariate analysis. However, only ECE of the SN metastasis was associated with NSN tumor involvement on multivariate analysis.

Conclusions

ECE of the SN metastasis is a strong predictor of NSN tumor involvement. All patients with ECE of the SN metastasis should undergo mandatory completion ALND.

Since Giuliano introduced intraoperative lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymphadenectomy (LM/SL) for breast cancer patients in 1993, 1 LM/SL has been emerging as the standard of care for patients with T1 or T2 (<5.0 cm) breast cancer. 2–7 Numerous institutions have demonstrated LM/SL to be a highly accurate method for predicting the tumor status of the axilla in patients with breast cancer. At institutions with a multidisciplinary sentinel node team comprised of nuclear medicine physicians, surgeons, and pathologists, if the sentinel node (SN) is tumor-free, the nonsentinel nodes (NSN) in the same axilla are highly unlikely to contain metastatic breast cancer. As a result, at centers with an experienced team, competent in LM/SL, patients with a tumor-free SN do not need to undergo completion axillary lymph node dissection (ALND).

However, when the SN reveals metastatic tumor, the tumor status of the NSN in the remainder of the axilla remains unknown. Consequently, to evaluate the NSN histopathologically, all patients with an SN metastasis must undergo level I and II completion ALND. For patients with a tumor-involved SN, the reported incidence of NSN tumor involvement varies greatly (27–68%). 2,3,5,6,8 As a result, if characteristics that reliably predict which patients with a tumor-involved SN have a high likelihood of NSN tumor involvement could be identified, it is possible that many breast cancer patients with a tumor-involved SN would not need to undergo completion ALND.

Several studies have attempted to identify predictors of NSN metastases in patients with a tumor-involved SN. Size of the primary tumor, 9–17 size of the SN metasta-sis, 9–14,16,18,19 number of tumor-involved SNs, 15,19 primary tumor lymphovascular invasion (LVI), 11,14,17,18 SN hilar tumor invasion, 14 and extracapsular extension (ECE) of the SN metastasis 18,20,21 have each been identified as predictors of NSN tumor involvement. While the strength of most of these predictors varies from study to study, ECE of the SN metastasis, when examined, is consistently associated with NSN tumor involvement. 18,20,21

We first investigated predictors of NSN tumor involvement when we completed our institutional validation trial for LM/SL of breast cancer patients. 21 We demonstrated that ECE of the SN metastasis, which had not been previously examined by other investigators, was highly predictive of NSN tumor involvement. Size of the SN metastasis was also identified as a predictor of NSN metastases in our initial series of patients. With our expanded LM/SL experience, we hypothesized that ECE of the SN metastasis and size of the SN metastasis can serve as strong predictors of NSN tumor involvement in breast cancer patients.

METHODS

Patient Selection

Between May 1998 and December 2001, all breast cancer patients who underwent LM/SL as part of their breast cancer care were prospectively enrolled in a University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, IRB-approved, breast cancer SN database. Review of this prospective database identified 260 patients with clinical T1 or T2 (<5 cm) invasive breast cancer who underwent successful LM/SL. Patients with unsuccessful LM procedures were excluded.

Surgical Technique

All patients underwent LM/SL using a combined isosulfan blue dye (Lymphazurin, Hirsch Industries, Inc., Richmond, VA) and technetium-labeled sulfur colloid (99mTcSC) (Nicomed Amersham Canada Ltd., Oakville, Ontario) technique, when technically feasible. The details of this procedure have been well described previously. 3,4,22 When the primary tumor was not palpable, patients underwent preoperative needle localization with subsequent ultrasound-guided 99mTcSC injection performed in the mammography suite. For patients with high upper outer quadrant lesions, 99mTcSC was used at the discretion of the operating surgeon. Routine preoperative lymphoscintigraphy was not performed. All patients underwent intraoperative LM with isosulfan blue dye (Lymphazurin). Intraoperatively, a curvilinear axillary incision was made using a hand-held Geiger counter to identify the area with the greatest number of counts per second. The underlying tissue was carefully dissected until a blue-stained lymphatic channel was identified. This channel was then followed proximally and distally until a blue node was located. If the ratio of the ex vivo SN counts to the background counts was less than 10:1 after removal of the SN, the dissection was continued to identify and remove any additional radioactive and/or blue SNs.

The first 74 patients were part of our institutional SN validation trial and underwent LM/SL followed by immediate completion ALND. For the 186 subsequent patients, ALND was offered as a delayed procedure to all patients with a tumor-involved SN. After completion of the validation trial, patients with a tumor-free SN received no further axillary therapy.

Handling and Histopathologic Examination of the SN and NSN

Our protocol for handling and histopathologic examination of the SN and its evolution have been described previously in detail. 22 Each SN was bivalved and subsequently sliced at intervals of 1.0 mm or less. Alternating slices were sent to the University of North Carolina Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center Tissue Procurement and Analysis Core Facility for future studies and to surgical pathology for permanent gross and histopathologic evaluation. The slices retained by surgical pathology were then serially sectioned and stained with hematoxylin-eosin (H&E). Immunohistochemical (IHC) cytokeratin stain, CAM 5.2 (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA), was used routinely for patients with invasive lobular carcinoma and selectively for all other tumor types.

The NSNs from the 74 patients who were part of our SN validation trial were serially sectioned and examined with H&E and IHC stains in a similar fashion to the SN. The NSNs from the subsequent 186 patients were examined at a minimum of one H&E-stained section per node.

Statistical Methods

Logistic regression was used to test the association between NSN tumor status and several clinical and histopathologic factors, including gender, age, number of tumor-involved SNs, size of primary tumor, size of SN metastasis, lymphovascular invasion, and ECE. Each factor was first tested individually for a significant association with NSN status. Continuous variables were analyzed using a univariate logistic regression model. Dichotomous variables were analyzed using the Pearson chi-square test (for ECE) or Fisher exact test (for gender). Significant univariate factors were then included in a multivariate logistic regression model. Logistic regression analyses were performed using the PROC LOGISTIC procedure in SAS, Version 8.02 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Pearson chi-square and Fisher exact tests were performed using the SAS PROC FREQ procedure.

Information about presence or absence of LVI was missing for 10 patients. On preliminary testing, LVI did not appear to have statistical significance or to significantly impact the multivariate analysis. As a result, LVI was dropped from the analysis to allow for inclusion of the additional patients and expansion of the dataset. Size of the SN metastasis was missing for two patients, so the final multivariate analysis was performed on a total of 68 of the 70 patients with a tumor-involved SN who underwent ALND.

RESULTS

A total of 260 patients (256 women, 4 men) with clinical T1 or T2 breast cancer underwent 263 LM/SL procedures; three women had bilateral disease. Their mean age was 56 years (range 26–91 years). The mean tumor size was 1.85 cm (range 0.1–11.3 cm).

An average of 2.0 SNs (range 1–8) were removed per patient. The SN contained tumor in 74 (28.1%) cases. Patients with SN metastases had, on average, 1.6 tumor-involved SNs (range 1–6). The mean size of SN metastasis was 6.9 mm (range 0.01–25 mm). ECE of the SN metastasis was present in 24.3% (18/74) of patients with a tumor-involved SN.

Seventy of the 74 patients with a tumor-involved SN underwent completion ALND before systemic adjuvant therapy. Two elderly patients with small primary tumors declined further axillary treatment after LM/SL. The other two patients had synchronous gastrointestinal and breast malignancies. One patient underwent neoadjuvant chemotherapy after colon resection, core breast biopsy, and LM/SL; she ultimately underwent ALND after neoadjuvant therapy. The other patient went directly to systemic adjuvant therapy after primary tumor resections and LM/SL; she never received a completion ALND.

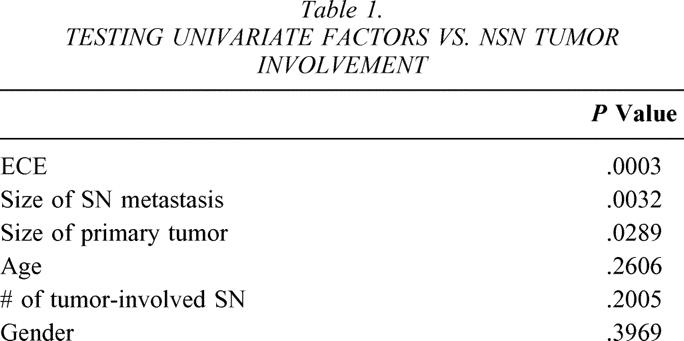

NSN tumor involvement was present in 41.4% (29/70) of patients with a tumor-involved SN who underwent ALND before systemic adjuvant therapy. On univariate analysis, size of the primary tumor and size of the SN metastasis, both examined as continuous variables, were significantly associated with NSN tumor involvement (P = .03 and P = .003, respectively;Table 1). ECE of the SN metastasis was also significantly associated with NSN tumor involvement on univariate analysis: 78% of patients with ECE of the SN metastasis had NSN tumor involvement, while only 29% of patients without ECE of the SN metastasis had NSN metastases (P = .0003). Additionally, ECE of the SN metastasis was significantly associated with a greater total number of tumor-involved axillary nodes (7.6 vs. 2.5, P = .006).

Table 1. TESTING UNIVARIATE FACTORS VS. NSN TUMOR INVOLVEMENT

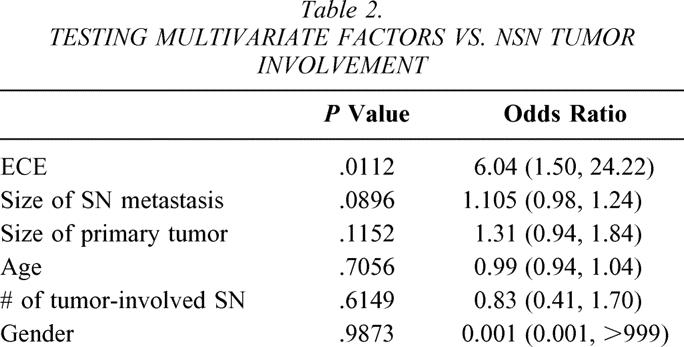

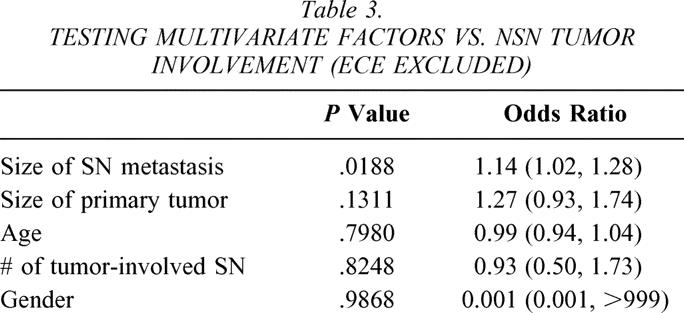

On multivariate analysis, only ECE of the SN metastasis was significantly associated with NSN tumor involvement (P = .01, odds ratio 6.04 [1.50, 24.22];Table 2). Patients with NSN tumor involvement tended to have larger SN metastases (9.4 mm vs. 4.9 mm), but this difference was not statistically significant on multivariate analysis. However, when ECE of the SN metastasis was excluded from the multivariate analysis, size of the SN metastasis was significantly associated with NSN tumor involvement (P = .02;Table 3).

Table 2. TESTING MULTIVARIATE FACTORS VS. NSN TUMOR INVOLVEMENT

Table 3. TESTING MULTIVARIATE FACTORS VS. NSN TUMOR INVOLVEMENT (ECE EXCLUDED)

DISCUSSION

The widespread use of LM/SL for breast cancer is allowing patients with T1 and T2 (<5 cm) tumors and a tumor-free SN to avoid the short- and long-term morbidity of completion ALND. Unfortunately, completion ALND is still necessary to determine the histopathologic tumor status of the NSN in patients with a tumor-involved SN. For a large percentage of these patients (27–68%) 2,3,5,6,8 with a tumor-involved SN, no NSN metastases will be identified. Recognizing the opportunity to identify another group of patients who might be able to avoid the morbidity of completion ALND, researchers began to look for predictors of NSN tumor involvement in patients with a tumor-involved SN.

The initial attempts to identify predictors of NSN tumor involvement demonstrated size of the primary tumor and size of the SN metastasis as potential predictors of NSN tumor involvement. 9,10 Chu et al. 9 examined multiple clinical and histopathologic characteristics in an attempt to find predictors of NSN tumor involvement in patients with a SN metastasis. Their study of 157 women demonstrated that a primary tumor larger than 2.0 cm and a SN metastasis larger than 2.0 mm were significantly associated with NSN tumor involvement (P = .01 and P = .0001, respectively). Similarly, Reynolds et al. 10 examined several clinical and histopathologic characteristics from 60 patients with primary breast cancer and a SN metastasis. They confirmed that a primary tumor larger than 2.0 cm and a SN metastasis larger than 2.0 mm were significantly associated with NSN tumor involvement (P = .0004 and P = 0.002, respectively).

Several subsequent studies have shown size of the SN metastasis 11–14,17–19 and size of the primary tumor 11–17 to be associated with NSN tumor involvement. Weiser et al., 11 in an analysis of 206 patients with a tumor-involved SN, found that both size of the SN metastasis and size of the primary tumor were significantly associated with NSN tumor involvement on multivariate analysis (P = .007 and P = .0002, respectively). Similarly, Kamath et al., 12 in an examination of 101 patients with a tumor-involved SN, found that while 58.3% of patients with a macrometastasis (>2.0 mm) had NSN tumor involvement, only 15.2% of patients with an SN metastasis 2.0 mm or smaller had NSN tumor involvement (P = .001). They also confirmed that size of the primary tumor was significantly associated with NSN tumor involvement (P = .005).

Overall, size of the SN metastasis and size of the primary tumor have been consistently identified as predictors of NSN tumor involvement. Unfortunately, neither of these characteristics, alone or in combination, has been demonstrated to be a strong enough predictor of NSN tumor involvement to identify a subset of patients who can safely forgo ALND. As a result, the search for predictors of NSN tumor involvement in patients with a tumor-involved SN has continued.

In 1999, we began investigating how factors historically reported to be prognostic for breast cancer patients translated to breast cancer patients treated in the SN era. Accordingly, we considered Fisher et al.’s 23 observation that ECE of axillary lymph node metastases is a valuable prognostic factor in breast cancer patients. In Fisher’s original study of 158 patients with axillary node metastases, a significant correlation existed between the presence of ECE and tumor involvement of more than three axillary nodes (P = .002). Many other studies have subsequently confirmed that the presence of ECE of axillary node metastases is significantly related to the total number of tumor-involved axillary nodes in breast cancer patients. 24–30

Our initial study, 21 presented to the Society of Surgical Oncology in 2000, was the first to examine the significance of ECE in the SN era. We examined ECE of the SN metastasis as a potential predictor of NSN tumor involvement. On multivariate analysis, we demonstrated that ECE of the SN metastasis was significantly associated with NSN tumor involvement (P = .041). Additionally, patients with ECE of the SN metastasis had a greater total number of tumor-involved axillary nodes than patients without ECE (P = .006).

Our current expanded dataset continues to support the strong association between ECE of the SN metastasis and NSN tumor involvement (P = .0003). While patients with no evidence of ECE of the SN metastasis had an average of 2.5 tumor-involved axillary nodes, patients with ECE of the SN metastasis had an average of 7.6 tumor-involved axillary nodes. This association was highly statistically significant (P = .0061).

Only two other published studies included ECE of the SN metastasis in their examination of predictors of NSN tumor involvement. Palamba et al., 20 in a study of 230 patients with a tumor-involved SN, found ECE of the SN metastasis to be significantly associated with NSN tumor involvement (P < .001). Additionally, they found that ECE of the SN metastasis was significantly associated with a greater total number of tumor-involved axillary nodes (P < .001). Similarly, Abdessalam et al., 18 in an examination of 100 patients with a tumor-involved SN, found that 84% of patients with ECE of the SN metastasis had NSN tumor involvement, while only 25% of patients without ECE had NSN tumor involvement (P < .001).

While only three groups have examined ECE of the SN metastasis as a potential predictor of NSN tumor involvement, all three have demonstrated that ECE of the SN metastasis is a powerful predictor of NSN metastases. Since Fisher et al.’s 23 initial report on ECE of axillary nodal metastases, clinicians have felt that tumors demonstrating ECE of the axillary nodal metastases represent a more biologically aggressive subset of breast cancers. The ability of nodal metastases to recruit degradation factors that permit the tumor to break through the lymph node capsule represents a very aggressive breast cancer tumor biology. Our current study suggests that this aggressive biologic feature far outweighs any other clinical or histopathologic factors examined as a predictor of the total axillary nodal tumor burden.

We were unable to confirm the associations between size of the SN metastasis and size of the primary tumor and NSN tumor involvement that have been previously reported. It is important to note, however, that previous studies demonstrating these associations did not consider ECE of the SN metastasis in their analyses. 9–12 While in our current study both size of the SN metastasis and size of the primary tumor were significantly associated with NSN tumor involvement on univariate analysis, these variables lost their significance on multiple logistic regression models that included ECE. However, when ECE was excluded from our multivariate analysis, size of the SN metastasis was significantly associated with NSN tumor involvement. This serves to emphasize ECE of the SN metastasis as a predictor of NSN tumor involvement. Until a superior predictor of NSN tumor involvement is identified, we believe that ECE of the SN metastasis should serve as the cornerstone for all future multivariate analyses.

The clinical implications of this data are important. Due to the high likelihood of extensive axillary tumor burden, all breast cancer patients with ECE of the SN metastasis should undergo a completion ALND. Conversely, patients with small SN metastases and no evidence of ECE are highly unlikely to harbor NSN metastases. As a result, the role of completion ALND in these patients is controversial. This important clinical question is being asked by the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group trial Z0011 (Protocol ACOSOG-Z0011. Phase III Randomized Study of Axillary Lymph Node Dissection in Women With Stage I or IIA Breast Cancer Who Have a Positive Sentinel Node, A. E. Giuliano, principal investigator). In this trial, patients with a tumor-involved SN are randomized to completion ALND or no additional axillary therapy. If this trial fails to demonstrate a survival advantage for patients undergoing ALND, then completion ALND for patients with a tumor-involved SN and no evidence of ECE may become obsolete, sparing many patients the short- and long-term morbidity associated with ALND.

CONCLUSIONS

Consistent with the historical experience from ALND specimens, ECE of the SN metastasis is strongly associated with a greater total number of tumor-involved axillary nodes. ECE is a biologic marker of aggressive nodal disease. Consequently, patients with ECE of the SN metastasis are highly likely to have NSN tumor involvement. As a result, completion ALND should always be recommended to patients with ECE of the SN metastasis, independent of other clinical and histopathologic factors, including size of the primary tumor and size of the SN metastasis.

Discussion

Dr. William C. Wood (Atlanta, GA): I first would congratulate the continued outworkings of the major contribution made by Drs. Giuliano and Morton to the entire approach that we take today to early breast cancer with the use of sentinel node mapping and the identification of the majority of women who do not have clinically involved nodes and do not need a axillary dissection. I would particularly like to congratulate the authors today, who were the first to describe extracapsular extension of metastases as the major prognostic factor that it is in telling us what the other lymph nodes are likely to be bearing. This was first presented at the Society of Surgical Oncology. They now have a confirmatory larger study, and two other authors have looked for the same thing and found it as well. So I think they have not only described this, it is now an established finding.

Not only have they done this, they have analyzed it very elegantly statistically. I guess I cavil, and apologize for being so picky, but as elegant as the statistics are, I would like to see the actual data.

I would be very interested in knowing, for example, of the 18 patients with extracapsular extension, what percent had nonsentinel node involvement versus the 56 patients who did not have extracapsular extension, what percent of those patients had positive nonsentinel nodes? The number of involved nonsentinel nodes was three times as great in those with extracapsular extension. The question is, what are the varying percentages?

Second, we have found in looking at long-term prognosis a difference between patients who have extracapsular extension, sort of gangbusters breaking out through the wall of the lymph node that is apparent on gross exam, and those sections you showed us that microscopically can be demonstrated to have breakthrough but when it is not grossly apparent. Did you find this? Have you looked for this in your studies?

Finally, a question as to the significance that is very impressive of extracapsular extension. This clearly represents a summation of several biologic factors of aggressiveness, just as lymph node numbers remain important because they are results of metastatic potential, unlike the things we find in the primary tumor. So lymph node number remains very important. Do you think it is possible that lymph node extension may actually overwhelm the number of involved lymph nodes as a prognostic factor for the late outcome of women?

Dr. Charles E. Cox (Tampa, FL): I congratulate the authors on the compilation of yet another excellent series of breast cancer patients which have been managed with sentinel node mapping and selective lymphadenectomy. We have now entered a new era of breast cancer management where sentinel lymph node mapping has become the standard of care in over 70% of cases treated at the major cancer centers in the United States, as reported to the NCCN data registry for breast cancer. With worldwide data in excess of 15,000 reported cases validating the technique, little question remains as to the use of the technique for axillary nodal staging.

Questions such as those addressed by the authors of this manuscript will begin to refine the use of sentinel node mapping for breast cancer. In their series of 260 patients in which 74, or 28%, had positive sentinel nodes, 18 of the 70, or 29%, demonstrated extracapsular extension, with a mean of 7.6 positive nodes per patient.

The authors have struck a familiar theme, which antedated sentinel node mapping, by trying to predict which patients may not need complete node dissection. Indeed, they have concluded the opposite; that is, the group of patients which definitely needs a complete axillary lymph node dissection. The data are clear that patients with extracapsular extension need a node dissection. How might that information be used to modify the treatment strategy for this group of patients with extracapsular extension of nodal disease?

From this data one might conclude that all patients with extracapsular extension of the sentinel node would be candidates for neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by complete node dissection. Clearly patients with this magnitude of nodal involvement will receive adjuvant chemotherapy, one third of which will be pathologically cleared of their axillary disease by that chemotherapy and in addition will have statistically improved survival.

My questions: Should extracapsular extension found in the sentinel node be used to stratify patients for treatment with neoadjuvant chemotherapy? Will complete axillary node dissection at the termination of the treatment be able to evaluate pathologic clearance of nodal disease as a means of determining prognostic stratification? Better stated, did all patients with extracapsular extension of the sentinel node have nonsentinel nodes which contained tumor?

Again I congratulate the authors for looking to the next level of questions of how the sentinel node data may be used for treatment strategy. I encourage all who manage breast cancer to put behind them the notion of who will not need an axillary node dissection and embrace lymphatic mapping. It is clear that those with negative sentinel nodes do not need axillary node dissection while those with positive sentinel nodes do, at least until the American College of Surgeons Z0011 randomized trial of node dissection based on a positive sentinel node is completed.

Dr. Kelly M. McMasters (Louisville, KY): In an analysis of over 2,000 patients with clinical stage T1 and T2 breast cancers, we found that overall 37% of the patients had positive nonsentinel nodes when the sentinel node was positive. These are real positive nonsentinel nodes identified on routine pathology with H&E staining. This is with a median tumor size in the same range of T1c.

Although we did not have data on the size of sentinel node metastasis, which is very clearly important, we couldn’t identify any subsets of patients with a minimal risk of nonsentinel node metastasis when the sentinel node was positive.

So my question is, could you identify any population of patients with a positive sentinel node who had a 0% chance of nonsentinel node metastasis?

Dr. David W. Ollila (Chapel Hill, NC): Dr. Wood and Dr. Cox, if you look at our patients with extracapsular extension of the sentinel node, 78% of those patients had nonsentinel node metastases. Conversely, if you looked at our patients that didn’t have extracapsular extension of the sentinel node, only 29% of those patients had a nonsentinel node metastasis.

And I think that dovetails into what Dr. McMasters was asking, can you identify a subset of patients that are at such a low risk to have disease in the remainder of the axilla that they don’t need axillary dissection? And the answer is No. No matter what the statisticians did looking at the variables, dichotomous or continuous variables, we were not able to come up with a subset of patients that you could obviate the need for axillary dissection. Conversely, though, we feel very strongly that the patients with ECE of the sentinel node metastasis should have a mandatory axillary dissection.

Dr. Wood, regarding your question regarding gross versus microscopic, we have not looked at it that way. I would like to go back, just as we have tried to quantitate the volume of the nodal metastasis, to try to quantitate the volume of extracapsular extension. Is this a 2-mm break in the node, or is one half or 75% of the node totally involved?

With regards to the absolute number of nodes involved, we need longer follow-up. I think if we look at this data set 3 years, 4 years, 5 years from now, I think we are going to have a better answer about the biology of patients with extracapsular extension, because we have been treating them as best we can in a routine manner in conjunction with our medical oncology and surgical oncology colleagues.

With regards to your question, Dr. Cox, the issue of the role of sentinel lymph node in patients with locally advanced breast cancer in conjunction with neoadjuvant chemotherapy is a very hot topic. Two weeks ago at the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group meeting in Phoenix, there was a very lively discussion regarding the role of a sentinel node: Should it come before the initiation of neoadjuvant chemotherapy? Should it come after the initiation of chemotherapy?

I think doing the sentinel node up front gives you insight into the biology, and now our medical oncology colleagues can tailor or plan what they are going to do and how much. I think it is an excellent idea to add different factors up front so we can learn as much biology. Because the M. D. Anderson data are very clear, the patients that do the best are the ones that have no axillary disease at the end of their therapy.

References

- 1.Giuliano AE. Lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymphadenectomy for breast cancer. San Antonio TX: American Surgical Association, 1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Giuliano AE, Kirgan DM, Guenther JM, et al. Lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymphadenectomy for breast cancer. Ann Surg. 1994; 220: 391–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Albertini JJ, Lyman GH, Cox C, et al. Lymphatic mapping and sentinel node biopsy in the patient with breast cancer. JAMA. 1996; 276: 1818–1822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turner RR, Ollila DW, Krasne DL, et al. Histopathologic validation of the sentinel lymph node hypothesis for breast carcinoma. Ann Surg. 1997; 226: 271–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krag D, Weaver D, Ashikaga T, et al. The sentinel node in breast cancer—a multicenter validation study. N Engl J Med. 1998; 339: 941–946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Veronesi U, Paganelli G, Viale G, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy and axillary dissection in breast cancer: results in a large series. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999; 91: 368–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Styblo TM, Wood WC. The management of ductal and lobular breast cancer. Surg Oncol. 1999; 8: 67–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ollila DB, Stitzenberg KB. Breast cancer sentinel node metastases: histopathologic detection and clinical significance. Cancer Control. 2001; 8: 407–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chu KU, Turner RR, Hansen NM, et al. Do all patients with sentinel node metastasis from breast carcinoma need complete axillary node dissection? Ann Surg. 1999; 229: 536–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reynolds C, Mick R, Donohue JH, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy with metastasis: can axillary dissection be avoided in some patients with breast cancer? J Clin Oncol. 1999; 17: 1720–1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weiser MR, Montgomery LL, Tan LK, et al. Lymphovascular invasion enhances the prediction of nonsentinel node metastases in breast cancer patients with positive sentinel nodes. Ann Surg Oncol. 2001; 8: 145–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamath VJ, Giuliano R, Dauway EL, et al. Characteristics of the sentinel lymph node in breast cancer predict further involvement of higher-echelon nodes in the axilla: a study to evaluate the need for complete axillary lymph node dissection. Arch Surg. 2001; 136: 688–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chu KU, Turner RR, Hansen NM, et al. Sentinel node metastasis in patients with breast carcinoma accurately predicts immunohistochemically detectable nonsentinel node metastasis. Ann Surg Oncol. 1999; 6: 756–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Turner RR, Chu KU, Qi K, et al. Pathologic features associated with nonsentinel lymph node metastases in patients with metastatic breast carcinoma in a sentinel lymph node. Cancer. 2000; 89: 574–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wong SL, Edwards MJ, Chao C, et al. Predicting the status of the nonsentinel axillary nodes: a multicenter study. Arch Surg. 2001; 136: 563–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chua B, Ung O, Taylor R, et al. Treatment implications of a positive sentinel lymph node biopsy for patients with early-stage breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2001; 92: 1769–1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sachdev U, Murphy K, Derzie A, et al. Predictors of nonsentinel lymph node metastasis in breast cancer patients. Am J Surg. 2002; 183: 213–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abdessalam SF, Zervos EE, Prasad M, et al. Predictors of positive axillary lymph nodes after sentinel lymph node biopsy in breast cancer. Am J Surg. 2001; 182: 316–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rahusen FD, Torrenga H, van Diest PJ, et al. Predictive factors for metastatic involvement of nonsentinel nodes in patients with breast cancer. Arch Surg. 2001; 136: 1059–1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palamba HW, Rombouts MC, Ruers TJ, et al. Extranodal extension of axillary metastasis of invasive breast carcinoma as a possible predictor for the total number of positive lymph nodes. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2001; 27: 719–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ollila DW, Stitzenberg KB, Iacocca MV, et al. Sentinel node metastasis with extracapsular extension can predict risk of nonsentinel node involvement in breast cancer patients. Poster presentation, Society of Surgical Oncology, New Orleans, LA, 2000.

- 22.Stitzenberg KB, Calvo BF, Iacocca MV, et al. Cytokeratin immunohistochemical validation of the sentinel node hypothesis in patients with breast cancer. Am J Clin Pathol. 2002; 117: 729–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fisher ER, Gregorio RM, Redmond C, et al. Pathologic findings from the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast project. (Protocol no. 4). III. The significance of extranodal extension of axillary metastases. Am J Clin Pathol. 1976; 65: 439–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Donegan WL, Stine SB, Samter TG. Implications of extracapsular nodal metastases for treatment and prognosis of breast cancer. Cancer. 1993; 72: 778–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leonard C, Corkill M, Tompkin J, et al. Are axillary recurrence and overall survival affected by axillary extranodal tumor extension in breast cancer? Implications for radiation therapy. J Clin Oncol. 1995; 13: 47–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pierce LJ, Oberman HA, Strawderman MH, et al. Microscopic extracapsular extension in the axilla: is this an indication for axillary radiotherapy? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995; 33: 253–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fisher BJ, Perera FE, Cooke AL, et al. Extracapsular axillary node extension in patients receiving adjuvant systemic therapy: an indication for radiotherapy? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997; 38: 551–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vicini FA, Horwitz EM, Lacerna MD, et al. The role of regional nodal irradiation in the management of patients with early-stage breast cancer treated with breast-conserving therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997; 39: 1069–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mignano JE, Zahurak ML, Chakravarthy A, et al. Significance of axillary lymph node extranodal soft tissue extension and indications for postmastectomy irradiation. Cancer. 1999; 86: 1258–1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hetelekidis S, Schnitt SJ, Silver B, et al. The significance of extracapsular extension of axillary lymph node metastases in early-stage breast cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000; 46: 31–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Footnotes

Presented at the 114th Annual Session of the Southern Surgical Association, December 1–4, 2002, Palm Beach, Florida.

Correspondence: David W. Ollila, MD, Assistant Professor of Surgery, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, CB#7210, 3010 Old Clinic Building, Chapel Hill, NC 27599.

E-mail: david_ollila@med.unc.edu

Accepted for publication December 2002.