Abstract

A gene from Azotobacter vinelandii whose product exhibits primary sequence similarity to the NifY, NafY, NifX, and VnfX family of proteins, and which is required for effective V-dependent diazotrophic growth, was identified. Because this gene is located downstream from vnfK in an arrangement similar to the relative organization of the nifK and nifY genes, it was designated vnfY. A mutant strain having an insertion mutation in vnfY has 10-fold less vnf dinitrogenase activity and exhibits a greatly diminished level of 49V label incorporation into the V-dependent dinitrogenase when compared to the wild type. These results indicate that VnfY has a role in the maturation of the V-dependent dinitrogenase, with a specific role in the formation of the V-containing cofactor and/or its insertion into apodinitrogenase.

Azotobacter vinelandii harbors three genetically distinct nitrogenase systems that are differentially expressed depending on the availability of metals in the medium: a nif-encoded Mo-containing nitrogenase, a vnf-encoded V-containing nitrogenase, and an anf-encoded iron-only nitrogenase (2). The V-containing nitrogenase contains an iron-vanadium cofactor (FeV-co) at its active site which is structurally and functionally analogous to the better-characterized FeMo-co of the Mo-dependent system. A functional V-containing nitrogenase requires the products of the structural genes for dinitrogenase (vnfDGK) and dinitrogenase reductase (vnfH) as well as several other nif and vnf gene products involved in the biosynthesis of FeV-co and the maturation of the nitrogenase component proteins. Much of what is known about the biosynthesis of FeV-co comes from analogous studies on FeMo-co biosynthesis. It is believed that the products of nifB, vnfN, vnfE, vnfH, vnfX, and nifV are involved in the biosynthesis of FeV-co (see reference 12 for a review).

The involvement of VnfX in the biosynthesis of FeV-co is of particular interest with respect to the results described here. A vanadium-iron-sulfur cluster presumed to be similar to a precursor of FeMo-co biosynthesis accumulates on VnfX during FeV-co biosynthesis (16). Upon homocitrate addition, a newly formed homocitrate- and vanadium-containing cluster is transferred from VnfX to apodinitrogenase; the resulting dinitrogenase is able to reduce acetylene (15). VnfX is also able to bind structurally related metalloclusters as NifB-co or FeMo-co. The exact role of VnfX in FeV-co biosynthesis is not yet known.

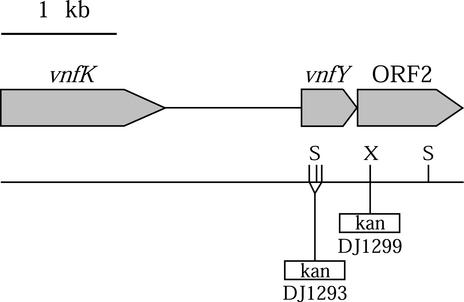

To identify vnf genes whose products are involved in formation of a functional V-containing nitrogenase, we determined the nucleotide sequence of the genomic region located downstream from the previously characterized vnfDGK genes. This analysis revealed the presence of two open reading frames (ORFs) (Fig. 1). The sequence obtained in this work was also confirmed by comparison to the preliminary sequences provided by the shotgun sequence analysis of the entire A. vinelandii genome. The first ORF encodes a 161-residue polypeptide exhibiting primary sequence similarity to the VnfX, NifX, NifY, and NafY family of proteins. Because of these similarities and its chromosomal location relative to the structural genes for the vnf dinitrogenase, this potential gene was designated vnfY. The second ORF encodes the ATP-binding subunit of an ABC-type transporter of unknown function. The vnfY gene and ORF2 show a 3-bp overlap, indicating that their expression is tightly coupled.

FIG. 1.

Structure of the A. vinelandii chromosome 3′ of the vnfDGK gene region. The locations of the kanamycin resistance cassette insertions within vnfY and ORF2 are indicated, together with the denomination (DJ) of the resulting mutant strain. S, SalI; X, XhoI.

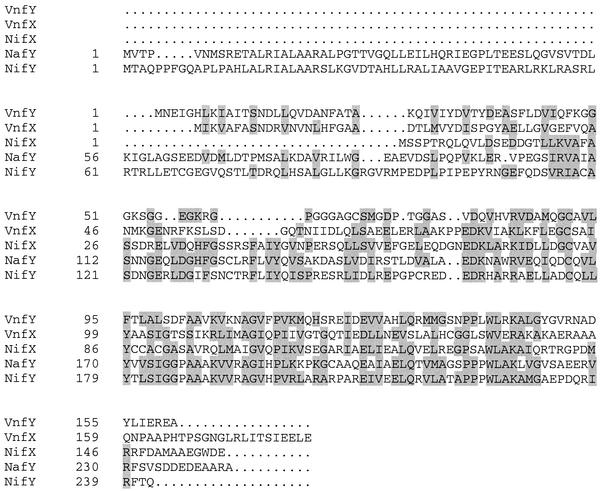

The primary sequences of VnfY and other members of this family are aligned in Fig. 2, which shows a conserved region that extends from amino acid residue 78 to residue 147 in the VnfY sequence. However, a comparison of the N-terminal regions shows similarity between NifY and NafY and between VnfY and VnfX but little similarity when all five proteins are compared altogether. Examination of the recently sequenced A. vinelandii genome reveals that NafY, NifY, NifX, VnfX, and VnfY represent the only members of this family of relatively small proteins. In addition, the nifB gene, and another gene of unknown function that bears primary sequence similarity to the nifB gene, also exhibits some primary sequence similarity to the nifX gene. The involvement of this family of proteins in the biosynthesis of FeMo-co or FeV-co was suggested based on the ability of certain of them to bind to FeMo-co, FeV-co, or their precursors and on the capacity of NifX to stimulate the in vitro synthesis of FeMo-co threefold (19). It has been also proposed that NafY and NifY are involved in the insertion of FeMo-co into the nif apodinitrogenase (7, 8). However, mutations in nafY, nifY, nifX, or vnfX have little or no effect on the formation of an active dinitrogenase under metal-sufficient growth conditions (8, 9, 14, 22).

FIG. 2.

Amino acid sequence alignment of VnfY, VnfX, NifX, NafY, and NifY proteins from A. vinelandii. The amino acid sequences are indicated by the single-letter code. Amino acid residues identical or similar in three or more of the aligned proteins are shaded in gray.

To assess the involvement of VnfY in maturation of the V-containing nitrogenase, vnfY was disrupted by insertion mutagenesis using a kanamycin resistance gene cartridge. Procedures for A. vinelandii transformation (11) and gene replacement (10) were performed as previously described, and strains used in this work are listed in Table 1. A. vinelandii mutant strain DJ1254 is a ΔnifDK, tungsten-tolerant strain derived from the CA11.6 and DJ33 strains. The tungsten-tolerant strain DJ1254 is used in this study because the expression of its V-dependent nitrogenase is less sensitive to Mo contamination in the culture medium than it is in strain DJ33, most probably due to a defect in Mo/W uptake into the cell. The DJ1293 strain was generated by transformation of DJ1254 with plasmid pDB1112, which contains a kanamycin resistance cassette inserted at the SalI sites within the vnfY gene. Strain DJ1299 was obtained by transformation of DJ1254 with plasmid pDB1119, which contains a kanamycin resistance cassette inserted at the XhoI site within ORF2.

TABLE 1.

A. vinelandii strains used in this work

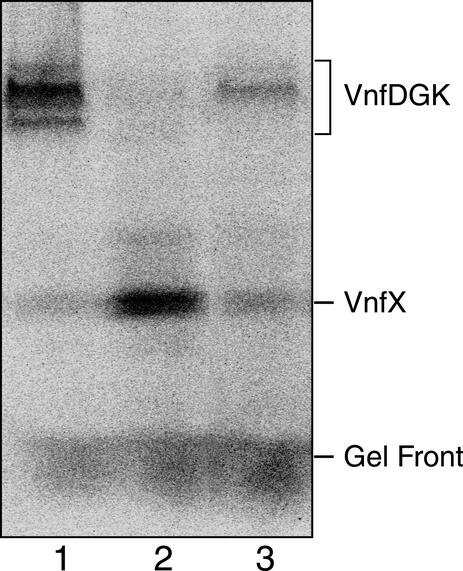

The distribution of protein-bound 49V radiolabel in crude extracts of A. vinelandii mutant strains was visualized by phosphorimage analysis of anoxic native gels. Strains CA12, CA11.1, and DJ1293 were grown in the presence of a fixed nitrogen source and then derepressed for vnf nitrogenase in Mo-deficient nitrogen-free medium containing 49VCl5 (0.5 to 1.0 mCi/ml in 6 N HCl; Los Alamos National Laboratories). Conditions for A. vinelandii growth and derepression of vnf nitrogenase have been described previously (16). Methods for cell extract preparation (18) and for analysis of 49V-radiolabeled proteins by anoxic native gel electrophoresis and phosphorimaging (1) have been described previously. Total levels of incorporation of 49V radiolabel into A. vinelandii cells were consistent with levels of incorporation observed in previous studies (16) and were similar in all mutant strains used in this study (data not shown). Therefore, the mutation in vnfY does not affect vanadium uptake by DJ1293 cells. However, strain DJ1293 exhibits only 12% of the 49V label accumulating on the V-containing dinitrogenase compared to strain CA12, which is wild type with respect to the vnf-encoded nitrogenase components (compare lanes 1 and 3 in Fig. 3). As previously observed (5), the vnf-encoded dinitrogenase runs as multiple bands when analyzed by anoxic native gel electrophoresis. The significance of this observation is not yet known. In control experiments using extracts prepared from CA12 and DJ1293 (developed with antibody to VnfD), sodium dodecyl sulfate-gel immunoblot analysis of vnf dinitrogenase revealed that the two strains accumulate similar levels of V-containing dinitrogenase (data not shown). Thus, insertional inactivation of vnfY prevents the effective incorporation of FeV-co into V-containing dinitrogenase without altering the accumulation of the corresponding polypeptides.

FIG. 3.

Phosphorimage analysis of a native anoxic gel of extracts from A. vinelandii mutant strains. Mutant strains were grown and vnf derepressed in the presence of 49VCl5, as described previously (16). A total of 900 μg of protein was loaded in each lane. Lane 1, CA12 (ΔnifHDK); lane 2, CA11.1 (ΔnifHDKvnfDGK::spc); lane 3, DJ1293 (ΔnifDKvnfY::Kan).

It was previously shown that the 49V radiolabel accumulates on VnfX when the structural genes for the V-containing dinitrogenase are deleted (16). In the present study, the amount of 49V radiolabel associated with VnfX in extracts of a strain from which vnfDGK was deleted (CA11.1) was fivefold larger than that for a strain having an insertion mutation within vnfY (DJ1293) (see Fig. 3, lanes 2 and 3, respectively). Moreover, the amount of 49V label found associated with VnfX in extracts of DJ1293 was only slightly larger than the amounts exhibited by extracts of CA12.

The dinitrogenase and dinitrogenase reductase activities in crude extracts of A. vinelandii strain DJ1293 were also determined and compared to those in extracts of strains CA12 and DJ54 (Table 2). Dinitrogenase and dinitrogenase reductase activities in cell extracts were obtained after titration with an excess of the complementary component as described previously (17). The specific activity of each protein is defined as nanomoles of ethylene formed per minute per milligram of protein in the extract. Extracts of strain DJ1293 were only able to reduce 1.3 nmol of acetylene/min/mg of protein when saturating amounts of dinitrogenase reductase were included in the assay. This value compares to 10 to 15 nmol of acetylene/min/mg of protein reduced by extracts of strains DJ54 and CA12, both wild-type strains for the vnf nitrogenase system. This result is in accordance with the levels of 49V radiolabel observed to be associated with vnf dinitrogenase in strains DJ1293 and CA12. Conversely, dinitrogenase reductase activity levels were in the same range in extracts of the DJ1293, DJ54, and CA12 strains, indicating that the mutation in vnfY does not affect vnf dinitrogenase reductase.

TABLE 2.

Activities of the vnf-encoded dinitrogenase and dinitrogenase reductase in extracts of various A. vinelandii mutant strains

| Straina | Acetylene reduction activity

|

|

|---|---|---|

| vnf-dinitrogenase (nmol/min/mg of protein) | vnf-dinitrogenase reductase (nmol/min/mg of protein) | |

| DJ54 (ΔnifH) | 9.8 ± 0.07 | 30.4 ± 3.1 |

| CA12 (ΔnifHDK) | 15.0 ± 2.4 | 27.1 ± 10.4 |

| DJ1293 (ΔnifDKvnfY::Kan) | 1.3 ± 1.1 | 19.1 ± 6.2 |

All strains were vnf derepressed. Reaction mixtures contained 0.2 ml of the appropriate cell-free extract. Dinitrogenase and dinitrogenase reductase activities in cell-free extracts were obtained after titration with an excess of the complementary component as described previously (17).

These results suggest that VnfY is involved in some aspect of the biosynthesis or insertion of FeV-co into the V-containing dinitrogenase. One possibility is that the function of VnfY with respect to the V-containing nitrogenase system is similar to the function of NifY/NafY in the Mo-dependent system—namely, to aid in the incorporation of finished cofactor into apodinitrogenase. If this were the only step impaired in the vnfY mutant strain, one would expect accumulation of 49V label on VnfX at levels similar to those found in a strain from which vnfDGK was deleted. However, our results indicate that loss of VnfY function results in a lower level of 49V incorporation into the V-containing dinitrogenase and also into VnfX. Furthermore, no other protein(s) is 49V labeled in extracts of DJ1293. Thus, it is possible that VnfY is involved in an early step in the biosynthesis of FeV-co, for example, in the incorporation of V into the pathway.

It is not surprising that VnfY might have more than one role in the biosynthesis of FeV-co. As noted above, some members of this family of proteins show functional versatility and seem to be involved in more than the binding of FeMo-co or FeV-co precursors only. For example, NifX and NifY have been proposed to have a role in balancing nif gene expression in Klebsiella pneumoniae (6, 20), and NafY acts like a chaperone that stabilizes the apo form of the nif dinitrogenase in A. vinelandii (7, 14). However, VnfY neither seems to regulate the expression of the vnf gene (since a vnfY mutant contains normal levels of VnfDGK protein) nor seems to act as a chaperone because it is not found associated with purified apo-VnfDGK (4).

Unlike the situation observed for the loss of NifY, NafY, NifX, or VnfX function, loss of VnfY function has a clear effect on the maturation of V-containing dinitrogenase which is reflected in a lower level of incorporation of FeV-co into the V-containing dinitrogenase and, consequently, in lower dinitrogenase activity. The vnfY mutant strain is clearly and consistently defective in V-dependent diazotrophic growth when tested in solid medium (data not shown). These effects are not due to a polar effect of the insertion mutation within vnfY on the ORF2, because insertional inactivation of ORF2 does not affect V-dependent diazotrophic growth (data not shown). These observations should provide a physiological and biochemical basis for determining the specific role of VnfY in V-containing dinitrogenase maturation, which should in turn provide insight into the possible roles of this family of proteins in the assembly and insertion of complex metalloclusters.

Acknowledgments

We thank Carolyn S. Brown for helping grow A. vinelandii strains.

This work was supported by grant GM35332 from NIGMS, National Institutes of Health (to P.W.L.), and grant MCB-9630127, National Science Foundation (to D.R.D).

REFERENCES

- 1.Allen, R. M., R. Chatterjee, P. W. Ludden, and V. K. Shah. 1995. Incorporation of iron and sulfur from NifB cofactor into the iron-molybdenum cofactor of dinitrogenase. J. Biol. Chem. 270:26890-26896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bishop, P. E., and R. Premakumar. 1992. Alternative nitrogen fixation systems, p. 736-762. In G. Stacey, R. H. Burris, and H. J. Evans (ed.), Biological nitrogen fixation. Chapman & Hall, New York, N.Y.

- 3.Bishop, P. E., R. Premakumar, D. R. Dean, M. R. Jacobson, J. R. Chisnell, T. M. Rizzo, and J. Kopczynski. 1986. Nitrogen fixation by Azotobacter vinelandii strains having deletions in structural genes for nitrogenase. Science 232:92-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chatterjee, R., R. M. Allen, P. W. Ludden, and V. K. Shah. 1996. Purification and characterization of the vnf-encoded apodinitrogenase from Azotobacter vinelandii. J. Biol. Chem. 271:6819-6826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chatterjee, R., P. W. Ludden, and V. K. Shah. 1997. Characterization of VNFG, the δ subunit of the vnf-encoded apodinitrogenase from Azotobacter vinelandii—implications for its role in the formation of functional dinitrogenase 2. J. Biol. Chem. 272:3758-3765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gosink, M. M., N. M. Franklin, and G. P. Roberts. 1990. The product of the Klebsiella pneumoniae nifX gene is a negative regulator of the nitrogen fixation (nif) regulon. J. Bacteriol. 172:1441-1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Homer, M. J., D. R. Dean, and G. P. Roberts. 1995. Characterization of the γ protein and its involvement in the metallocluster assembly and maturation of dinitrogenase from Azotobacter vinelandii. J. Biol. Chem. 270:24745-24752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Homer, M. J., T. D. Paustian, V. K. Shah, and G. P. Roberts. 1993. The nifY product of Klebsiella pneumoniae is associated with apodinitrogenase and dissociates upon activation with the iron-molybdenum cofactor. J. Bacteriol. 175:4907-4910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacobson, M. R., K. E. Brigle, L. T. Bennett, R. A. Setterquist, M. S. Wilson, V. L. Cash, J. Beynon, W. E. Newton, and D. R. Dean. 1989. Physical and genetic map of the major nif gene cluster from Azotobacter vinelandii. J. Bacteriol. 171:1017-1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacobson, M. R., V. L. Cash, M. C. Weiss, N. F. Laird, W. E. Newton, and D. R. Dean. 1989. Biochemical and genetic analysis of the nifUSVWZM cluster from Azotobacter vinelandii. Mol. Gen. Genet. 219:49-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Page, W. J., and M. von Tigerstrom. 1979. Optimal conditions for transformation of A. vinelandii. J. Bacteriol. 139:1058-1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rangaraj, P., C. Rüttimann-Johnson, V. K. Shah, and P. W. Ludden. 2000. Biosynthesis of the iron-molybdenum and iron-vanadium cofactors of the nif- and vnf-encoded nitrogenases, p. 55-79. In E. W. Triplett (ed.), Prokaryotic nitrogen fixation: a model system for analysis of a biochemical process. Horizon Scientific Press, Wymondham, United Kingdom.

- 13.Robinson, A. C., D. R. Dean, and B. K. Burgess. 1987. Iron-molybdenum cofactor biosynthesis in Azotobacter vinelandii requires the iron protein of nitrogenase. J. Biol. Chem. 262:14327-14332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rubio, L. M., P. Rangaraj, M. J. Homer, G. P. Roberts, and P. W. Ludden. 2002. Cloning and mutational analysis of the γ gene from Azotobacter vinelandii defines a new family of proteins capable of metallocluster binding and protein stabilization. J. Biol. Chem. 277:14299-14305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rüttimann-Johnson, C., P. Rangaraj, V. K. Shah, and P. W. Ludden. 2001. Requirement of homocitrate for the transfer of a 49V-labeled precursor of the iron-vanadium cofactor from VnfX to nif-apodinitrogenase. J. Biol. Chem. 276:4522-4526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rüttimann-Johnson, C., C. R. Staples, P. Rangaraj, V. K. Shah, and P. W. Ludden. 1999. A vanadium and iron cluster accumulates on VnfX during iron-vanadium-cofactor synthesis for the vanadium nitrogenase in Azotobacter vinelandii. J. Biol. Chem. 274:18087-18092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shah, V. K., and W. J. Brill. 1973. Nitrogenase. IV. Simple method of purification to homogeneity of nitrogenase components from Azotobacter vinelandii. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 305:445-454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shah, V. K., L. C. Davis, and W. J. Brill. 1972. Nitrogenase. I. Repression and derepression of the iron-molybdenum and iron proteins of nitrogenase in Azotobacter vinelandii. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 256:498-511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shah, V. K., P. Rangaraj, R. Chatterjee, R. M. Allen, J. T. Roll, G. P. Roberts, and P. W. Ludden. 1999. Requirement of NifX and other nif proteins for in vitro biosynthesis of the iron-molybdenum cofactor of nitrogenase. J. Bacteriol. 181:2797-2801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simon, H. M., M. M. Gosink, and G. P. Roberts. 1999. Importance of cis determinants and nitrogenase activity in regulated stability of the Klebsiella pneumoniae nitrogenase structural gene mRNA. J. Bacteriol. 181:3751-3760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Waugh, S. I., D. M. Paulsen, P. V. Mylona, R. H. Maynard, R. Premakumar, and P. E. Bishop. 1995. The genes encoding the delta subunits of dinitrogenases 2 and 3 are required for Mo-independent diazotrophic growth by Azotobacter vinelandii. J. Bacteriol. 177:1505-1510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolfinger, E. D., and P. E. Bishop. 1991. Nucleotide sequence and mutational analysis of the vnfENX region of Azotobacter vinelandii. J. Bacteriol. 173:7565-7572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]