Abstract

Objective

To assess the impact on birth size and risk of low birth weight of alternative combinations of micronutrients given to pregnant women.

Design

Double blind cluster randomised controlled trial.

Setting

Rural community in south eastern Nepal.

Participants

4926 pregnant women and 4130 live born infants.

Interventions

426 communities were randomised to five regimens in which pregnant women received daily supplements of folic acid, folic acid-iron, folic acid-iron-zinc, or multiple micronutrients all given with vitamin A, or vitamin A alone (control).

Main outcome measures

Birth weight, length, and head and chest circumference assessed within 72 hours of birth. Low birth weight was defined <2500 g.

Results

Supplementation with maternal folic acid alone had no effect on birth size. Folic acid-iron increased mean birth weight by 37 g (95% confidence interval −16 g to 90 g) and reduced the percentage of low birthweight babies (<2500 g) from 43% to 34% (16%; relative risk=0.84, 0.72 to 0.99). Folic acid-iron-zinc had no effect on birth size compared with controls. Multiple micronutrient supplementation increased birth weight by 64 g (12 g to 115 g) and reduced the percentage of low birthweight babies by 14% (0.86, 0.74 to 0.99). None of the supplement combinations reduced the incidence of preterm births. Folic acid-iron and multiple micronutrients increased head and chest circumference of babies, but not length.

Conclusions

Antenatal folic acid-iron supplements modestly reduce the risk of low birth weight. Multiple micronutrients confer no additional benefit over folic acid-iron in reducing this risk.

What is already known on this topic

Deficiencies in micronutrients are common in women in developing countries and have been associated with low birth weight and preterm delivery

What this study adds

In rural Nepal maternal supplementation with folic acid-iron reduced the incidence of low birth weight by 16%

A multiple micronutrient supplement of 14 micronutrients, including folic acid, iron, and zinc, reduced low birth weight by 14%, thus conferring no advantage over folic acid-iron

Introduction

Birth weight is closely associated with the health and survival of infants in the developing world, where 90% of the 250 million low birthweight babies (<2500 g) are born each year.1 Studies of food supplementation have typically reported increases in birth weight of 25-84 g per 10 000 kcal of maternal energy intake during pregnancy,2 although mean increases of about 135 g may occur with higher energy intakes.3,4

The effects of maternal micronutrient supplementation on birth weight and intrauterine growth have not been well studied, despite the potential benefits of such interventions on pregnancy outcomes. Individual micronutrients such as folic acid, zinc, iron, and vitamin A have received attention. An overview of five controlled trials showed a 40% reduction in the prevalence of intrauterine growth retardation with folic acid supplementation, although these trials were small and not well designed.5 Recent trials in Bangladesh6 and Peru7 did not confirm the improvement in birth weight with antenatal zinc supplementation reported in previous studies. The efficacy of iron supplementation in improving pregnancy outcome is currently debated. Although there is evidence for lower birth weight among mothers with anaemia, there are no data to establish a causal association.8 A randomised placebo controlled trial in Niger showed no improvement in birth weight after maternal iron supplementation during pregnancy, although length at birth increased.9 We have reported that maternal vitamin A or β carotene supplementation failed to influence either infant mortality10 or neonatal weight11 but was associated with a 44% reduction in pregnancy related maternal mortality.12

Unicef is currently promoting antenatal use of multiple micronutrient supplements among women in the developing world. Providing a full complement of micronutrients is expected to optimise functional and health benefits to the mother and infant. Yet data are lacking on the efficacy of such a supplement in improving pregnancy outcomes.

We assessed the impact of daily antenatal supplementation with folic acid, folic acid-iron, folic acid-iron-zinc, or a multiple micronutrient supplement (containing 14 micronutrients including folic acid, iron, and zinc), all with vitamin A, compared with vitamin A alone (as control) on mean birth weight and percentage of low birthweight babies. We also examined other outcomes, including maternal and infant morbidity and micronutrient status (results not shown here). All pregnant women received vitamin A because it is known to reduce pregnancy related mortality in this population.12

Methods

Study design and population

The study was a double blind cluster randomised controlled trial conducted in the south eastern plains district of Sarlahi, Nepal, from December 1998 to the end of April 2001. We originally estimated that we would need a sample size of 600 pregnancies per treatment arm to detect a difference of ⩾100 g in birth weight between each of the four treatments compared with control. This was calculated according to two tailed α=0.05 and β=0.20, birth weight SD 500 g, 10% fetal loss, 15% loss to follow up, and 20% design effect associated with cluster randomisation.10,12 However, at the outset of the trial we increased the number of pregnancies per group to 1000 per group so that we could examine survival into the 1st year. This allowed a minimum detectable difference of 75 g in birth weight with 80% power. To achieve this sample size in a one year period we defined as the study area 426 sectors, each of 75-150 households located in 30 “village development communities.” Randomisation was done in blocks of five within each community to insure geographical balance across groups. We randomised sectors to the five different supplement arms by drawing numbered identical chips from a hat.

Eligibility and surveillance of pregnancy

All women of reproductive age were first screened by 426 local female workers (“sector distributors”) to assess how likely it was that they would become pregnant over the next 12 months. Women who were currently pregnant, breast feeding a baby <9 months old, menopausal, sterilised, or widowed were excluded. Remaining women were registered and visited by sector distributors at home every five weeks for a year and were asked if they had menstruated in the previous month. If not, women underwent a urine test (human chorionic gonadotrophin antigen; Clue, Orchid Biomedical Systems, Goa, India) to ascertain pregnancies. Throughout the trial, women were added to the registry and pregnancy surveillance when they married.

At baseline newly identified pregnant women were asked to recall morbidity, diet, alcohol and tobacco use, and household chores performed in the previous seven days; and weight, height and mid-upper arm circumference were recorded. During the third trimester, morbidity, diet, and other exposure histories and weight and mid-upper arm circumference were recorded.

Intervention

Sectors were randomly assigned for women to receive one of the following five micronutrient supplements: folic acid (400 μg), folic acid-iron (60 mg ferrous fumarate), folic acid-iron-zinc (30 mg zinc sulphate), or multiple folic acid-iron-zinc plus vitamin D 10 μg, vitamin E 10 mg, vitamin B-1 1.6 mg, vitamin B-2 1.8 mg, niacin 20 mg, vitamin B-6 2.2 mg, vitamin B-12 2.6 μg, vitamin C 100 mg, vitamin K 65 μg, copper 2.0 mg, magnesium 100 mg) all with vitamin A, and vitamin A alone (1000 μg) as the control.

The amount of each nutrient in the supplement was the recommended dietary allowance for pregnant or lactating woman,13 except for iron and zinc. The iron dose used was that recommended in areas where the prevalence of anaemia is >40%.14 The zinc dosage achieved a 1:2 ratio with iron to minimise competitive absorption between these nutrients.15

The supplements were identical in appearance and participants, investigators, field staff, and statisticians did not know supplement codes until the study finished. Midway through the trial, the supplements were tested and found to be within 4% of the expected concentration for each nutrient.

At enrolment, each woman received 15 caplets in a bottle with instructions to take one caplet every night before bedtime. Sector distributors visited women twice each week to monitor supplement intake and replenish supplies of 15 caplets. The number added each time was summed over the duration time in the trial (for up to 12 weeks after a live birth and ⩾ five weeks after a miscarriage or stillbirth) to estimate compliance.

Birth weight and other anthropometric measures

Most births occurred at home, assisted by traditional birth attendants, relatives, and neighbours.12 Once a birth was reported, the anthropometrist visited to record “day of birth” measurements. Weight was measured to the nearest 2 g on a digital scale (Seca 727, Hamburg, Germany), which was checked before each weighing against standard weights. Recumbent length was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm on a length board (Shorr Infant Measuring Board, Shorr Productions, Rhode Island, USA). Chest and head circumferences were measured to the nearest 0.1 cm with an insertion tape (Ross Laboratories, Columbus, Ohio, USA). For all measurements except weight we used the median of three values in analyses.

Low birth weight was defined as weight <2500 g measured within 72 hours of birth. Small for gestational age babies were defined as those whose weight was below the 10th centile of the gestational age sex specific US reference for fetal growth.16 Gestational age was calculated from the reported first day of the last menstrual period, obtained at the baseline interview, and checked against the week of the positive pregnancy test and prospectively collected histories of menstruation. Preterm delivery was defined as delivery before 37 weeks of gestation.

Statistical analysis

We compared baseline characteristics of pregnant women and median compliance rates (proportion of all eligible days of doses consumed) across treatment groups.

Data were analysed on an intention to treat basis. Mean differences in birth weight, length, and head and chest circumference were estimated with a generalised estimating equation linear model17 with exchangeable correlation to account for the fact that we randomised sectors, rather than individuals, to treatment groups. We repeated analyses adjusting for maternal weight at baseline, which differed by chance among treatment group (see table 1). The adjusted mean differences were estimated relative to the vitamin A (control) group. To estimate the relative risk and 95% confidence intervals for low birth weight, small for gestational age, and prematurity, we fitted generalised estimating equations binomial regression models with a log link and exchangeable correlation using treatment indicator variables (vitamin A being the referent group) with and without maternal weight as covariates. The overall treatment effects for each outcome were tested with the likelihood ratio test. All analyses were done with SAS version 6.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Table 1.

Characteristics of pregnant women by treatment group. Figures are number* (percentage) of women

| Control

|

Folic acid

|

Folic acid-iron

|

Folic acid-iron-zinc

|

Multiple micronutrients

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of pregnancies | 1037 | 929 | 940 | 982 | 1038 |

| Age at baseline (years): | |||||

| ⩽19 | 320 (31) | 292 (32) | 275 (29) | 297 (30) | 289 (28) |

| 20-29 | 532 (52) | 483 (52) | 522 (56) | 527 (54) | 568 (55) |

| ⩾30 | 178 (17) | 150 (16) | 139 (15) | 158 (16) | 178 (17) |

| Socioeconomic status: | |||||

| Literate | 220 (22) | 177 (19) | 194 (21) | 198 (20) | 188 (18) |

| Own land | 739 (73) | 733 (78) | 759 (81) | 728 (75) | 773 (75) |

| Low caste | 130 (13) | 112 (12) | 96 (10) | 135 (14) | 138 (13) |

| Parity: | |||||

| 0 | 275 (27) | 255 (28) | 237 (25) | 252 (26) | 265 (26) |

| 1-2 | 371 (36) | 338 (37) | 380 (41) | 381 (39) | 388 (38) |

| ⩾3 | 372 (37) | 330 (36) | 317 (34) | 338 (35) | 376 (37) |

| Diet (at least twice in previous week): | |||||

| Meat/fish | 202 (21) | 178 (21) | 162 (19) | 178 (20) | 211 (21) |

| Yellow fruits/vegetables† | 181 (19) | 151 (18) | 156 (18) | 180 (20) | 171 (17) |

| Substance use (in previous week): | |||||

| Smoked cigarettes | 153 (16) | 160 (19) | 146 (17) | 135 (15) | 160 (16) |

| Drank alcohol | 44 (5) | 59 (7) | 54 (6) | 50 (6) | 58 (6) |

| Place of delivery: | |||||

| Home | 783 (94) | 688 (93) | 687 (92) | 719 (92) | 795 (91) |

| Health facility | 35 (4) | 38 (5) | 41 (6) | 49 (6) | 45 (5) |

| Other | 19 (2) | 18 (2) | 20 (3) | 17 (2) | 30 (3) |

Numbers of women vary because of missing values.

Mango, papaya, pumpkin (ripe).

Results

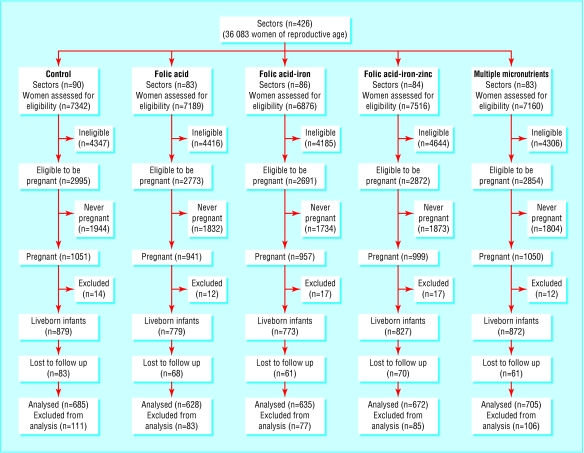

Of 36 083 women of reproductive age, 14 185 were identified as likely to become pregnant (figure). Over a year, 4998 pregnancies were confirmed by urine testing. Of these, six were false positive, three had unknown outcomes, and 63 ended as induced abortions and were excluded. Of the remaining, 4096 resulted in at least one live birth. The numbers of twin pregnancies (34 pairs of live born twins and eight pairs with one stillborn) were comparable across treatment groups. In all, 830 pregnancies (16.8%) ended in miscarriage, stillbirth, or maternal death. Of the 4130 live born infants, about 80% were measured within 72 hours and 70% within 24 hours of birth.

Baseline maternal characteristics were similar except for small differences in ethnic composition and land holding (table 1). Gestation and anthropometric variables were similar, except women in the control group weighed slightly less (table 2).

Table 2.

Maternal anthropometric measures and gestation at baseline by treatment group

| Control

|

Folic acid

|

Folic acid-iron

|

Folic acid-iron-zinc

|

Multiple micronutrients

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No

|

Mean (SD)

|

No

|

Mean (SD)

|

No

|

Mean (SD)

|

No

|

Mean (SD)

|

No

|

Mean (SD)

|

|||||

| Weight (kg)* | 944 | 42.9 (5.6) | 852 | 43.7 (5.9) | 866 | 43.9 (5.6) | 899 | 43.4 (5.5) | 983 | 43.2 (5.4) | ||||

| Height (cm)* | 942 | 150.1 (5.7) | 852 | 150.5 (5.6) | 865 | 150.3 (5.4) | 899 | 150.5 (5.7) | 984 | 149.8 (5.4) | ||||

| BMI | 941 | 19.0 (2.1) | 852 | 19.3 (2.2) | 864 | 19.4 (2.0) | 899 | 19.1 (2.0) | 983 | 19.2 (2.0) | ||||

| MUAC (cm)* | 940 | 21.8 (1.8) | 850 | 21.9 (1.9) | 865 | 22.0 (1.8) | 898 | 21.9 (1.8) | 984 | 21.9 (1.8) | ||||

| Gestation (weeks) | 1020 | 11.2 (5.1) | 901 | 11.5 (5.3) | 928 | 11.3 (5.1) | 963 | 11.4 (5.1) | 1035 | 11.6 (5.1) | ||||

BMI=body mass index (weight/height2).

MUAC=mid-upper arm circumference.

Data missing on weight for 382 women, on height for 384 women, and on MUAC for 391 women.

Compliance with supplementation during pregnancy was high (median 88%) and did not vary by treatment (table 3). There were few self reported side effects, and the prevalence of nausea, vomiting, constipation, gastrointestinal distress, dizziness, and diarrhoea ranged from 0-4% and was comparable by treatment group. Dark stools were more common in women in the folic acid-iron group (4.2%; relative risk 3.0, 95% confidence interval 1.3 to 7.1) and the multiple micronutrient group (3.2%; 2.3, 1.0 to 5.2) compared with in the control group (1.5%). The prevalence of dark stools was 0.5% and 1.6% in the folic acid and folic acid-iron-zinc groups, respectively.

Table 3.

Compliance with supplements during pregnancy. Figures for compliance are numbers (percentage) of women

| Control

|

Folic acid

|

Folic acid-iron

|

Folic acid-iron-zinc

|

Multiple micronutrients

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of women | 1037 | 929 | 940 | 982 | 1038 |

| Compliance: | |||||

| 0% | 56 (5.4) | 46 (5.0) | 46 (4.9) | 40 (4.1) | 41 (3.9) |

| 1-25% | 88 (8.5) | 70 (7.5) | 53 (5.6) | 67 (6.8) | 64 (6.2) |

| 26-50% | 86 (8.3) | 71 (7.6) | 75 (8.0) | 76 (7.7) | 79 (7.6) |

| 51-75% | 138 (13.3) | 134 (14.4) | 153 (16.3) | 127 (12.9) | 136 (13.1) |

| 76-100% | 669 (64.5) | 608 (65.5) | 613 (65.2) | 672 (68.5) | 718 (69.2) |

| Mean (SD) | 72.7 (31.5) | 74.2 (30.4) | 74.9 (29.4) | 75.8 (29.2) | 76.2 (28.9) |

| Median (interquartile range) | 86.1 (60.3-96.3) | 88.2 (61.2-96.8) | 87.8 (63.4-96.5) | 88.2 (65.2-96.6) | 88.2 (67.1-97.0) |

Compared with the control group, folic acid supplementation had no effect on birth size except for a small decrement in birth length (−0.32 cm, −0.58 cm to −0.05 cm) (table 4). Birth weight in the folic acid-iron group was 37 g (−16 g to 90 g) higher than in the control group. Chest circumference (0.35 cm, 0.09 cm to 0.61 cm) and head circumference (0.16 cm, −0.03 cm to 0.34 cm) were also higher. There was no difference in length. Folic acid-iron-zinc supplementation had no apparent effect on any aspect of birth size compared with the control group. Birth weight was 53 g (0 g to 108 g) higher in the folic acid-iron group compared with the folic acid-iron-zinc group. Birth weight in the multiple micronutrients group was 64 g (12 g to 115 g) higher, as were chest (0.36 cm, 0.11 cm to 0.61 cm) and head (0.19 cm, 0.02 cm to 0.37 cm) circumference but not length (0.14 cm, −0.10 cm to 0.39 cm). The effects of supplementation with folic acid-iron and multiple micronutrients may have differed in the distribution of the added weight at birth, with multiple micronutrients increasing weight disproportionately at the upper end. There were 50% more infants in the multiple micronutrient group who weighed ⩾3300 g compared with the control group (relative risk=1.5, 0.96 to 2.2). Proportions in the folic acid-iron group were similar to the control group (1.1, 0.72 to 1.8).

Table 4.

Newborn anthropometry measured within 72 hours of birth by treatment group*

| Mean (SD)

|

Difference†

|

Difference‡ (95% CI)

|

P value§

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight (g) | |||||

| Control | 2587 (445) | — | — | 0.0014 | |

| Folic acid | 2587 (429) | −7 | −20 (−71 to 32) | ||

| Folic acid-iron | 2652 (436) | 60 | 37 (−16 to 90) | ||

| Folic acid-iron-zinc | 2598 (428) | 1 | −11 (−63 to 40) | ||

| Multiple micronutrients | 2659 (446) | 64 | 64 (12 to 115) | ||

| Length (cm) | |||||

| Control | 47.2 (2.32) | — | — | 0.0061 | |

| Folic acid | 46.9 (2.42) | −0.29 | −0.32 (−0.58 to −0.05) | ||

| Folic acid-iron | 47.4 (2.48) | 0.16 | 0.05 (−0.25 to 0.34) | ||

| Folic acid-iron-zinc | 47.2 (2.38) | −0.04 | −0.10 (−0.35 to 0.16) | ||

| Multiple micronutrients | 47.4 (2.31) | 0.16 | 0.14 (−0.10 to 0.39) | ||

| Chest circumference (cm) | |||||

| Control | 30.4 (2.05) | — | — | <0.0001 | |

| Folic acid | 30.4 (2.13) | 0.03 | −0.04 (−0.29 to 0.21) | ||

| Folic acid-iron | 30.8 (2.19) | 0.41 | 0.35 (0.09 to 0.61) | ||

| Folic acid-iron-zinc | 30.4 (2.05) | 0.05 | 0.001 (−0.26 to 0.26) | ||

| Multiple micronutrients | 30.8 (2.06) | 0.36 | 0.36 (0.11 to 0.61) | ||

| Head circumference (cm) | |||||

| Control | 32.5 (1.46) | — | — | 0.0123 | |

| Folic acid | 32.5 (1.40) | 0.03 | −0.004 (−0.18 to 0.19) | ||

| Folic acid-iron | 32.7 (1.44) | 0.20 | 0.16 (−0.03 to 0.34) | ||

| Folic acid-iron-zinc | 32.6 (1.46) | 0.05 | 0.01 (−0.17 to 0.20) | ||

| Multiple micronutrients | 32.7 (1.40) | 0.21 | 0.19 (0.02 to 0.37) | ||

No=685, 628, 635, 672, and 705 for control, folic acid, folic acid-iron, folic acid-iron-zinc, and multiple micronutrients, respectively.

Difference from control adjusted for design effect.

Difference from control adjusted for maternal weight at baseline and design effect.

Using likelihood ratio test (χ2 with 4 df) to determine whether five groups differ significantly from each other.

As we expected, the increases in birth weight among the folic acid-iron and multiple micronutrient groups translated into modest reductions in the proportions of low birthweight babies (<2500 g) of 16% (relative risk 0.84, 0.72 to 0.99) and 14% (0.86, 0.74 to 0.99), respectively (table 5). There was also a lower incidence of small for gestational age babies in the folic acid-iron group than in the control group (0.91, 0.83 to 1.00). There was no discernable effect on preterm births, all relative risks being about 1.0.

Table 5.

| No (%)

|

Relative risk (95% CI)†

|

P value‡

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Low birth weight (<2500 g) | |||

| Control | 685 (43.4) | 1.0 | 0.0103 |

| Folic acid | 628 (41.7) | 1.00 (0.88 to 1.15) | |

| Folic acid-iron | 635 (34.3) | 0.84 (0.72 to 0.99) | |

| Folic acid-iron-zinc | 672 (39.4) | 0.96 (0.83 to 1.11) | |

| Multiple micronutrients | 705 (35.3) | 0.86 (0.74 to 0.99) | |

| Small for gestational age§ | |||

| Control | 685 (58.7) | 1.0 | 0.1712 |

| Folic acid | 628 (57.8) | 1.02 (0.93 to 1.11) | |

| Folic acid-iron | 633 (51.7) | 0.91 (0.83 to 1.00) | |

| Folic acid-iron-zinc | 670 (56.4) | 0.98 (0.89 to 1.08) | |

| Multiple micronutrients | 704 (53.8) | 0.95 (0.87 to 1.04) | |

| Preterm (gestational age at birth <37 wk) | |||

| Control | 685 (20.4) | 1.0 | 0.7725 |

| Folic acid | 628 (22.1) | 1.08 (0.86 to 1.40) | |

| Folic acid-iron | 633 (23.1) | 1.13 (0.90 to 1.40) | |

| Folic acid-iron-zinc | 670 (20.2) | 0.99 (0.80 to 1.29) | |

| Multiple micronutrients | 704 (20.6) | 1.01 (0.82 to 1.26) | |

Data on gestational age missing for five babies.

Adjusted for maternal weight and design effect.

Using likelihood ratio test (χ2 with 4 df) to determine whether three groups differ significantly from each other.

Below 10th centile of US national reference for fetal growth.23

Discussion

We examined the effects of maternal supplementation with micronutrients on birth weight in rural Nepal, where over two fifths (43%) of babies weigh less than 2500 g at birth as estimated from the incidence of low birth weight in the control group. After supplementation the incidence of low birth weight was 34% in the folic acid-iron group, and was 35% in the multiple micronutrient group, corresponding to modest declines of 16% and 14%, respectively. From our results we calculate that 11 women would need to take folic acid-iron supplements (or 12 to take multiple micronutrient supplements) to avert one low birthweight baby. Neither combination of supplements seemed to affect linear growth, although measures of head and chest circumference were higher in these groups than in the control group.

Study strengths

This was a double blind randomised controlled trial that was adequately powered to examine modest reductions in the incidence of low birth weight. Our results are more generalisable than hospital based studies of birth weight. We achieved high accuracy and precision in the birth measurements in a setting where 90% of births occurred in remote village homes. The high quality of field performance was reflected by a median 88% maternal compliance with supplementation. Randomisation generated comparable groups with respect to most assessed factors, except for the lower baseline maternal weight (up to 1 kg) among women in the control group. This probably occurred by chance, and we adjusted for it in the analysis. Loss to follow up due to neonatal death and delay in measurement resulting from women leaving to deliver at their parental homes resulted in 20% of the newborns not being weighed or being weighed later than the 72 hour criteria for measuring birth weight.

In Nepal mean maternal weight is low (about 43.5 kg), probably because of energy and protein malnutrition. Micronutrient supplementation alone ameliorated the burden of low birth weight by 14-16%. What are the possible health or survival benefits of such an effect? Across different populations, low birthweight infants experience 4-10 times the risk of neonatal death.18 However, direct assessment of survival is needed as increases in birth weight may not always result in improved health or survival.19 In the present study we followed infants through the first six months of life and found differences in survival by treatment group that were not significant and were apparently unrelated to birth weight (Christian et al, unpublished).

As folic acid alone failed to affect birth weight, we attributed the observed effects on birth size to treatment of maternal iron deficiency. Anaemia and iron deficiency are known to stimulate the synthesis of corticotropin releasing hormone, which in turn increases fetal cortisol and inhibits fetal growth.20 Iron deficiency also increases oxidative damage to erythrocytes and the fetoplacental unit, which may result in intrauterine growth retardation and preterm delivery.20 Iron supplementation may improve maternal appetite,21 thereby increasing energy consumption during pregnancy with resultant increased intrauterine growth.

We do not know why the observed effects of folic acid-iron on birth size were absent with added zinc, though competition between bivalent iron and zinc for mucosal uptake, described previously,15,22 may be an explanation. However, multiple micronutrients, which included iron, zinc and presumably their interactions, did increase birth weight and other measures of growth, suggesting that mechanisms responsible for this effect may have involved pathways dependent more on other micronutrients than iron. For example, thiamine and vitamins B-6 and B-12 provided in the supplement have a role in numerous aspects of intermediary protein and energy metabolism, which could affect fetal growth.23

Our findings may be most relevant to rural South and, possibly, South East Asia, where prevalence of iron deficiency anaemia and low birth weight are high. In these settings iron supplementation may be effective in reducing, by a modest degree, the incidence of low birth weight. It is noteworthy that a fairly large array of micronutrients failed to reduce the risk of low birth weight beyond that achieved by folic acid-iron alone. Micronutrients beyond this combination should be added only if there is evidence of a health benefit.

Figure.

Study design, participation, and follow up. Women ineligible for inclusion were those who were currently pregnant, breast feeding an infant <9 months old, sterilised, menopausal, or widowed. Women who were excluded after diagnosis of pregnancy were those who turned out to have false positive pregnancy, had unknown outcomes, or had induced abortions. Lost to follow up included instances where birth weight was not obtained because infant died, mother refused, or home was inaccessible. Any data excluded from analysis at the final stage was due to birth weight being measured after 72 hours after birth

Acknowledgments

The following members of the Nepal study team contributed to the successful implementation of the study: Tirtha Raj Shakya and Rabindra Shrestha (field managers); Uma Shankar Sah, Arun Bhetwal, Gokarna Subedi, and Dhrub Khadka (field supervisors); and Jaibar Shrestha (laboratory in charge) and the rest of the laboratory team as well as the area coordinators, team leader interviewers, drivers, and administrative support staff. Sanu Maiya Dali and James Tielsch provided insights to the study design and procedures. Gwendolyn Clemens was responsible for computer programming and data management. Ravi Ram, Seema Rai, and Sunita Pant helped in data cleaning and supervision. Lee Wu helped with statistical analysis.

Footnotes

Funding: This study was carried out under cooperative agreement HRN-A-00-97-00015-00 between Office of Health and Nutrition, US Agency for International Development (USAID), Washington, DC, and the Center for Human Nutrition (CHN), Department of International Health, and the Sight and Life Research Institute, Johns Hopkins University, Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, USA. It was a joint undertaking between the CHN and the National Society for the Prevention of Blindness, Kathmandu, Nepal, under the auspices of the Social Welfare Council of His Majesty's Government of Nepal. The study was funded by USAID and received additional support from the Unicef Country Office, Kathmandu, Nepal, and Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. The supplements were provided by Roche, Brazil, and manufactured by NutriCorp International, C E Jamieson, Canada. The guarantor accepts full responsibility for the conduct of the study, had access to the data, and controlled the decision to publish.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: The study was approved by the National Health Research Council of the Ministry of Health of Nepal and the Committee for Human Research at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. A data safety and monitoring committee approved the trial's continuation midway through the trial. Informed consent was obtained from the participants at each interview.

References

- 1.Child Health Research Project. Special Report. Reducing perinatal and neonatal mortality. Report of a meeting. Baltimore, MD: Child Health Research Project; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lechtig A, Yarbrough C, Delgado H, Habicht JP, Martorell R, Klein RE. Influence of maternal nutrition on birth weight. Am J Clin Nutr. 1975;28:1223–1233. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/28.11.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lechtig A, Habicht JP, Delgado H, Klein RE, Yarbrough C, Martorell R. Effect of food supplementation during pregnancy on birth weight. Pediatrics. 1975;56:508–520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ceesay SM, Prentice AM, Cole TJ, Foord F, Weaver LT, Poskitt EM, et al. Effects on birth weight and perinatal mortality of maternal dietary supplements in rural Gambia: 5 year randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 1997;315:786–790. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7111.786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Onis M, Villar J, Gulmezoglu M. Nutritional interventions to prevent intrauterine growth retardation: evidence from randomized controlled trials. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1988;52 (suppl 1):S83–S93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Osenderp SJM, van Raaij JMA, Arifeen SE, Wahed MA, Baqui AH, Fuch GJ. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of the effect of zinc supplementation during pregnancy and on pregnancy outcome in Bangladeshi urban poor. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71:114–119. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.1.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caulfield LE, Zavaleta N, Figueroa A, Leon Z. Maternal zinc supplementation does not affect size at birth and pregnancy duration in Peru. J Nutr. 1999;129:1563–1568. doi: 10.1093/jn/129.8.1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rasmussen KM. Is there a causal relationship between iron deficiency or iron deficiency anaemia and weight at birth, length of gestation and perinatal mortality? J Nutr. 2001;131:590–603S. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.2.590S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Preziosi P, Prual A, Golan P, Daouda H, Boureima H, Hercberg S. Effect of iron supplementation on the iron status of pregnant women: consequences for newborns. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;66:1178–1182. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/66.5.1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katz J, West KP, Jr, Khatry SK, Pradhan EK, LeClerq SC, Christian P, et al. Low-dose vitamin A or beta-carotene supplementation does not reduce early infant mortality: a double-masked, randomized, controlled community trial in Nepal. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71:1570–1576. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.6.1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dreyfuss ML, West KP, Jr, Katz J, LeClerq SC, Pradhan EK, Adhikari RK, et al. Report of the XVIII International Vitamin A Consultative Group Meeting. Cairo, Egypt. ISLI Research Foundation, Washington DC. 1997. Effects of maternal vitamin A or β-carotene supplementation on intrauterine/neonatal and early infant growth in Nepal (abstract) [Google Scholar]

- 12.West KP, Jr, Katz J, Khatry SK, LeClerq SC, Pradhan EK, Shrestha SR, et al. Double blind, cluster randomised trial of low dose supplementation with vitamin A or beta carotene on mortality related to pregnancy in Nepal. The NNIPS-2 Study Group. BMJ. 1999;318:570–575. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7183.570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Research Council. Recommended dietary allowances. 10th ed. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stoltzfus RJ, Dreyfuss ML. Guidelines for the use of iron supplements to prevent and treat iron deficiency anaemia. Washington DC: INACG/WHO/Unicef: ILSI Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Solomons NW, Ruz M. Zinc and iron interaction: concepts and perspectives in the developing world. Nutr Res. 1997;17:177–185. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alexander GR, Himes JH, Kaufman RB, Mor J, Kogan M. A United States national reference for fetal growth. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87:163–168. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00386-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ashworth A. Effects of intrauterine growth retardation on mortality and morbidity in infants and young children. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1998;52 (suppl 1):S34–S42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garner P, Kramer MS, Chalmers I. Might efforts to increase birth weight in undernourished women do more harm than good? Lancet. 1992;340:1021–1022. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)93022-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Allen LH. Biological mechanisms that might underlie iron's effects on fetal growth and preterm birth. J Nutr. 2001;131:581–59S. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.2.581S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lawless JW, Latham MC, Stephenson LS, Kinoti SN, Pertet AM. Iron supplementation improves appetite and growth in anemic Kenyan primary school children. J Nutr. 1994;124:645–654. doi: 10.1093/jn/124.5.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Solomons NW. Competitive interaction of iron and zinc in the diet: consequences for human nutrition. J Nutr. 1986;116:927–935. doi: 10.1093/jn/116.6.927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramakrishnan U, Manjrekar R, Rivera J, Glonzales-Cossio T, Martorell R. Micronutrients and pregnancy outcome: a review of literature. Nutr Res. 1999;19:103–159. [Google Scholar]