After the introduction of Bassini's procedure in the late 19th century, methods of repairing hernias changed little until the 1990s, when synthetic mesh and laparoscopic methods arrived.1 In contrast to the open mesh technique, laparoscopic surgery remains uncommon. In January 2001, the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) issued guidance that stated, “For repair of primary inguinal hernia, open [mesh] should be the preferred surgical procedure.”2 We describe patterns of surgical repair of inguinal hernias and assess the impact of NICE's guidance.

Methods and results

We found 217 000 cases with a primary procedure code for primary surgery for an inguinal hernia from the hospital episode statistics database for England from April 1998 to December 2001. Of these, secondary procedure codes for minimal access surgery identified 8960 (4.1%) cases in which surgery was laparoscopic.

We used the software package SAS to do interrupted time series analysis on the rate of laparoscopic repairs as a proportion of all primary repairs of inguinal hernias, weekly, at 143 time points before publication of the NICE guidance and at 51 time points after. We also examined the effects of the NICE guidance on the overall rate of laparoscopic repair of hernias, assuming no change in case mix. A first order autoregressive model gave the best fit.

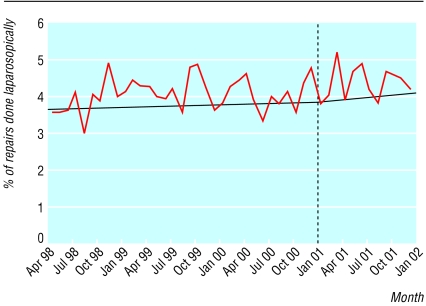

Publication of the NICE guidance did not reduce the proportion of repairs done laparoscopically. Before the NICE guidance, the rate of laparoscopic as a proportion of all repairs was increasing slowly and non-significantly by 0.08% (95% confidence interval −0.09% to 0.26%) per year. After issue of the guidance the rate increased slightly to 0.14% (0.02% to 0.25%) per year (figure).

The pattern was similar in the effects of NICE guidance on the overall use of laparoscopic repair of hernias. Before publication of the guidance, the annual increase in the number of laparoscopic repairs was 3.4 (−3.3 to 10.0) procedures, and afterwards the annual rate of increase rose slightly to 4.4 (0.0 to 8.6) procedures. Rates before and after did not differ significantly (P=0.6).

Comment

Guidance from NICE on laparoscopic repair of hernias had no impact on practice during the first year after publication. Despite the clarity of the advice given on laparoscopic hernia repair, on this occasion, NICE guidance did not achieve the desired change in clinical practice. Resistance to the guidance is illustrated by an appeal lodged to NICE and other articles 3; however, it is in areas of uncertainty and controversy that NICE should provide guidance.

Laparoscopic repair of hernias is a small part of NHS practice, but if our findings are applicable to other areas on which NICE has published guidance, NICE needs more active dissemination and implementation procedures. Guidance from NICE could be incorporated more directly into systems of clinical governance in the NHS.

Our analysis shows that routinely collected data can be used in clinical governance. Chief executives and medical directors of trust hospitals have access to hospital episode statistics and could use these data to monitor implementation of guidance as part of clinical governance. To improve evidence based practice in the NHS, guidance must be implemented more efficiently and clinical practice should be reviewed and monitored using well validated data.

Figure.

Primary surgery for inguinal hernia repairs done laparoscopically as a percentage of all repairs done from April 1998 to November 2001, before and after the publication of NICE guidance in January 2001

Acknowledgments

KB and AM thank the late H Brendan Devlin (1932-98) for valuable discussions about health services research in general and hernia repair in particular. We all thank Anne Burton for administrative support.

Footnotes

Funding: KB is funded by a Medical Research Council Special Training Fellowship in Health Services Research and by the Department of Health Policy R&D programme, which also partially supports AM.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Devlin HB, Kingsnorth A, O'Dwyer PJ, Bloor K. Management of abdominal hernias. London: Chapman and Hall Medical; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Guidance on the use of laparoscopic surgery for inguinal hernia. London: NICE; 2001. . (Technology appraisal guidance No 18.) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Motson R. Why does NICE not recommend laparoscopic herniorraphy? BMJ. 2002;324:1092–1094. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7345.1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]