Abstract

Loss of heterozygosity (LOH) is a common genetic alteration in tumors and often extends several megabases to encompass multiple genetic loci or even whole chromosome arms. Based on marker and karyotype analysis of tumor samples, a significant fraction of LOH events appears to arise from mitotic recombination between homologous chromosomes, reminiscent of recombination during meiosis. As DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) initiate meiotic recombination, a potential mechanism leading to LOH in mitotically dividing cells is DSB repair involving homologous chromosomes. We therefore sought to characterize the extent of LOH arising from DSB-induced recombination between homologous chromosomes in mammalian cells. To this end, a recombination reporter was introduced into a mouse embryonic stem cell line that has nonisogenic maternal and paternal chromosomes, as is the case in human populations, and then a DSB was introduced into one of the chromosomes. Recombinants involving alleles on homologous chromosomes were readily obtained at a frequency of 4.6 × 10−5; however, this frequency was substantially lower than that of DSB repair by nonhomologous end joining or the inferred frequency of homologous repair involving sister chromatids. Strikingly, the majority of recombinants had LOH restricted to the site of the DSB, with a minor class of recombinants having LOH that extended to markers 6 kb from the DSB. Furthermore, we found no evidence of LOH extending to markers 1 centimorgan or more from the DSB. In addition, crossing over, which can lead to LOH of a whole chromosome arm, was not observed, implying that there are key differences between mitotic and meiotic recombination mechanisms. These results indicate that extensive LOH is normally suppressed during DSB-induced allelic recombination in dividing mammalian cells.

A common genetic alteration in tumor cells is loss of heterozygosity (LOH), in which genetic information at a chromosomal locus is derived from only one parental chromosome rather than from both parental chromosomes (18, 25). LOH can involve large segments of chromosomes and therefore lead to a substantial loss of allele-specific genetic information. LOH is one of the genetic alterations commonly observed in sporadic tumors, and it is also presumed to be an obligate step in tumorigenesis in several familial cancer syndromes involving tumor suppressor genes. For example, individuals carrying one mutated RB allele in the germ line are at high risk of developing retinoblastoma, with tumors displaying loss of the wild-type RB allele.

Potential mechanisms of LOH can be inferred from combined analyses of tumor karyotypes and markers that are polymorphic between parental chromosomes. Researchers analyzing human cancers have inferred that LOH arises from several pathways, including chromosomal deletion, mitotic nondisjunction, and recombination between homologous chromosomes (18, 25). In retinoblastoma, recombination and nondisjunction appear to be common pathways (42 and 51% of LOH events, respectively, in one large study) (15); however, a recent study of colorectal cancers found that deletions associated with chromosome structural aberrations are more common (52). Each of these pathways has also been implicated in generating LOH in mouse models, with mitotic recombination predominating in many of these cases (18, 46). Despite the implication of several pathways in the generation of LOH, little is understood about the molecular events that lead to LOH, including those involving mitotic recombination pathways.

Chromosomal double-strand breaks (DSBs) are extremely potent inducers of homologous recombination in mammalian cells (17), raising the issue of whether they are the causative lesions for LOH by allelic recombination. During meiosis, DSBs generated by the Spo11 protein induce a high frequency of recombination between homologous chromosomes (20). Although Spo11 is expressed primarily during meiosis (21, 44), DSBs can be generated in nonmeiotic cells in several ways, for example, by oxygen free radicals, topoisomerase failure, radiation treatment, and DNA replication. Repair of these mitotic DSBs by homologous recombination involves strand invasion of a broken end into a homologous sequence which templates repair by gene conversion (17, 38) and thus can be termed homology-directed repair (HDR).

In mitotically dividing mammalian cells, the identical-sister chromatid is the most frequently used template for HDR (19). HDR involving the sister restores the intact chromatid without loss of sequence information, making this a very precise type of repair. High-fidelity repair is not guaranteed, however, when the template for HDR is the allele on the homologous chromosome, since maternal and paternal chromosomes are not identical in individuals. Such events can lead to LOH of large chromosome segments or even whole chromosome arms when recombination between the homologs is associated with either crossing over or extensive gene conversion without crossing over. DSBs have previously been shown to induce HDR between homologous chromosomes in mammalian cells at a recombination reporter, resulting in LOH at the reporter (35). However, in that study the full extent of LOH could not be determined because the two chromosomes were isogenic outside of the reporter substrate.

In this report, we sought to test whether HDR in mammalian cells leads to extensive LOH by using a reporter for DSB-induced allelic recombination. The reporter was introduced into a mouse embryonic stem (ES) cell line derived from an F1 hybrid of two different inbred mouse strains, BALB/c and 129/Sv, such that the maternal and paternal chromosomes contain polymorphic markers. Overall, the heterology between the two strains is estimated at approximately one single-nucleotide polymorphism per 1,050 bp (27), which is within the range of diversity in the human population (estimated at one single-nucleotide polymorphism per 1,000 to 2,000 bp) (45). We find that although spontaneous recombination at the allelic positions is not detectable, DSBs are potent inducers of allelic recombination. Examination of a number of markers indicates that the majority of recombinant clones have LOH restricted to the site of the DSB, although 2% of recombinants exhibit LOH extending to a marker 6 kb from the DSB. Importantly, we find no evidence of LOH extending to polymorphic markers 1 centimorgan (cM) or more from the DSB nor do we find evidence for crossing over between alleles. These results indicate that extensive LOH is suppressed during HDR of a DSB in mammalian cells. Thus, either DSBs are not the causative lesions for extensive LOH events arising from recombination between homologous chromosomes or the suppression of extensive LOH can be relieved under some circumstances.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell line construction.

The Rb targeting vectors for the S/P cell line were constructed by a series of subcloning steps. First, oligonucleotides with two tandem loxP sites (22) and a BglII site in between the loxP sites were inserted between the BamHI and SalI sites at the 3′ end of the neo genes in both the S2neo and Pneo vectors (43). Subsequently, a hyg gene from vector 129Rb-hyg (51) was cloned as a BglII fragment between the loxP sites to form the S2neo-loxP-hyg-loxP and Pneo-loxP-hyg-loxP cassettes. Then, NheI restriction sites were inserted into the 5′ end of each of these cassettes at the XhoI site and into the 3′ ends of the cassettes at the SalI site for the S2neo cassette and at the HindIII site, which is 14 bp downstream of the SalI site, for the Pneo cassette. These cassettes were then inserted into genomic fragments of the Rb locus at the NheI site in intron 18, with the S2neo cassette cloned into a genomic fragment isolated from a 129 strain to form the SH targeting vector and the Pneo cassette cloned into a genomic fragment isolated from a BALB/c strain to generate the PH targeting vector (51). Both neo cassettes were cloned in the same orientation as the Rb gene.

The S/P cell line was generated with four steps of genome manipulation. First, the SH targeting vector (70 μg; linearized with HpaI) was electroporated into the v17.2 cell line (54) (5 × 106 ES cells suspended in 700 μl of phosphate-buffered saline [PBS] in a 0.4-cm-path-length cuvette) by pulsing the cells at 800 V and 3 μF. Hygromycin selection was applied 24 h later at 150 μg/ml. After 10 days, surviving colonies were isolated and analyzed for targeting to Rb as previously described (51). Subsequently, the hyg gene was deleted by recombination between the loxP sites, as initiated by electroporation of 50 μg of a Cre expression vector (pCAGGS-Cre) (1) into 5 × 106 SH cells suspended in 700 μl of PBS in a 0.4-cm-path-length cuvette, followed by pulsing the cells at 250 V and 950 μF. The transfected cells were plated at low density, and after 10 days, colonies were isolated and screened for sensitivity to 150 μg of hygromycin/ml. Loss of the hyg gene to form the S cell line was confirmed by Southern blotting of HindIII/StuI-digested genomic DNA with an EcoRI/NcoI fragment of the neo gene as a probe. Using the PH targeting vector and the same steps described above for the generation of the S allele, the P allele was then created by targeting the S cell line.

DSB induction of allelic recombination and I-SceI site loss.

To measure the repair of an I-SceI-generated DSB, 50 μg of the I-SceI expression vector pCBASce (43) was mixed with 5 × 106 ES cells suspended in 650 μl of PBS in a 0.4-cm-path-length cuvette, followed by pulsing the cells at 200 V and 950 μF. Transfected cells were split to four or five 10-cm-diameter plates. At 24 h, one plate was trypsinized and counted to determine the number of cells that had survived electroporation. For the rest of the plates, G418 was applied at 200 μg/ml 24 h after transfection. After 8 to 10 days, surviving colonies were either stained and counted or expanded for further analysis. Allelic recombination frequencies were determined by dividing the number of G418-resistant colonies by the number of cells that survived electroporation.

To determine the percentage of I-SceI site loss for each electroporation, the neo gene of the S allele was amplified from genomic DNA from cells that had been electroporated with the I-SceI expression vector and grown without G418 for 5 days. Genomic DNA (1 μg) was used as the template for PCR with 40 ng of each primer in a reaction volume of 25 μl. The primers for amplification were rb1 (5′ AGGAATGCAGAGTTCTGCTTTAGC) and p6+ (5′ GAGAAGGGATTGGTTTTTGTTTTCG). Amplifications were performed using PCR beads (Amersham Pharmacia) in the Mastercycler PCR system (Eppendorf). Amplification was for a total of 35 cycles, using a 1-min elongation time and a 58.1°C annealing temperature. Following amplification, PCR products were digested with I-SceI for 20 h with 10 U of I-SceI (Roche) and separated on a 1% agarose gel. The gel was stained with ethidium bromide, and the ethidium signals for the I-SceI-resistant and I-SceI-cleaved bands were quantified with a Bio-Rad Chemidoc 2000 system with rolling disk background subtraction.

Genotypic analysis of polymorphic markers.

The genotype of a number of markers was determined through analysis of genomic DNA isolated from individual G418-resistant clones and also from the parental S/P cell line. The genotypes of a number of these markers involved amplification and resolution of PCR products, which was performed as described above for I-SceI site loss but using different sets of primers. The genotype of the NcoI/I-SceI site was determined using the primers rb1 and p6− (5′ ATACTTGAGAAGGGATTGGTTTTTG), followed by cleavage of the PCR product with NcoI or I-SceI. The genotype of the H3 marker was determined using the primers rb1 and p6−, followed by cleavage of the PCR product with HindIII. The genotype of the P6 marker was determined using the rb1 and p6+ primers. The genotypes of the Rbtg-repeat marker were determined using the primers rbtg1 (5′ GAATTCACCAATGAGGTCCCATAG) and rbtg2 (5′ CAGATGCCAATATCGACTGAAAAG). The genotypes of the D14Mit160, D14Mit224, and D14Mit95 markers were determined using primer sets whose sequences were published previously (4). The amplification products of the TG-repeat markers were separated on 3% Metaphor agarose gels (BioWhittaker Molecular Applications). The genotype of the St marker was determined by Southern blotting of genomic DNA cleaved with StuI by using an EcoRI/NcoI fragment of the neo gene as a probe.

Crossing-over analysis.

To test for crossing over in the crossover 1 (co1) interval, the neo genes of individual G418-resistant clones were amplified with the rb1 and p6+ primers followed by cleavage of the PCR product with EagI or PacI. To test for a crossing-over event in the interval co2, 8 μg of genomic DNA from individual G418-resistant clones was cleaved with StuI and separated on a 1% agarose gel. For each sample, genomic DNA of approximately 4 to 5 kb was isolated followed by purification of the DNA from the gel slice by using the High Pure PCR product purification kit (Roche). The neo genes were amplified from this size-enriched genomic DNA by using primers ep1 (5′ CCAATGTCGAGCAAACCCCGCC) and ep2 (5′ GCGTATGCAGCCGCCGCATTGC), followed by cleavage of the PCR product with EagI or PacI.

RESULTS

Allelic recombination reporter for homologous chromosomes.

Using an S2neo/Pneo substrate design (43), we developed a system to analyze both the frequency and extent of LOH due to DSB-induced allelic recombination in mammalian cells. In this design, a DSB is formed in vivo by expressing the rare-cutting endonuclease I-SceI, whose 18-bp recognition site has been integrated into a chromosome as a disrupting mutation in the 3′ end of the neomycin resistance gene (S2neo). Repair of the I-SceI-induced DSB by recombination can be directed by the homologous Pneo gene, itself an inactive neo gene due to insertion of a PacI site in the 5′ end of the gene. This repair event results in the replacement of the I-SceI site with wild-type neo sequences, giving rise to a functional neo+ gene, such that recombinants are selectable using the drug G418.

To study recombination events between alleles on homologous chromosomes, the S2neo and Pneo genes were gene targeted to allelic positions at the Rb locus on chromosome 14 in a cell line in which the homologous chromosomes contain polymorphic markers (Fig. 1A). Specifically, we used an ES cell line isolated from F1 hybrid mouse embryos, cell line v17.2, in which one set of chromosomes is derived from the 129/Sv strain and the other set is from the BALB/c strain (54). Strain differences between the chromosomes include restriction fragment polymorphisms at the Rb locus (51) as well as a number of short-sequence-length-polymorphism (SSLP) markers throughout chromosome 14 (4, 54).

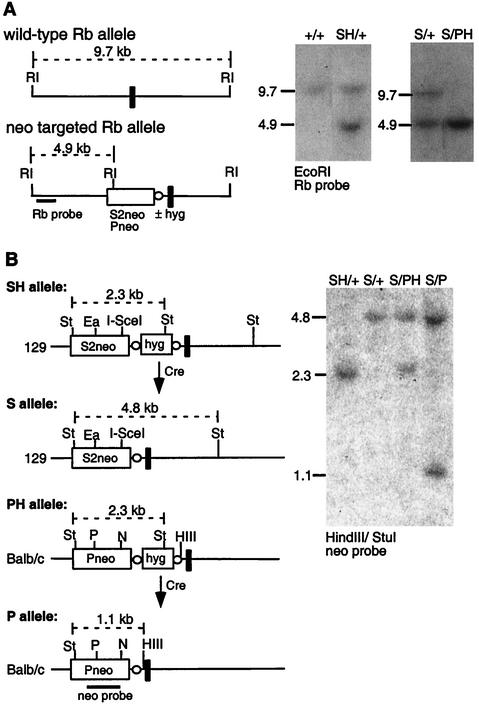

FIG. 1.

Allelic recombination reporter for homologous chromosomes. (A) Allelic recombination substrates S2neo and Pneo were sequentially targeted to the 129/Sv and BALB/c alleles, respectively, of the Rb locus in the mouse ES cell line v17.2. Southern blot hybridization was performed with the indicated Rb probe fragment, which is located outside the targeting fragments, for detection of wild-type and targeted alleles from an EcoRI digest of genomic DNA. Targeting with either S2neo or Pneo gives rise to an EcoRI fragment of the same size. The neo genes are inserted upstream of exon 19 (vertical black bar) at a site which appears to be nondisrupting for Rb expression (35). (B) Both targeting events used a linked hygromycin resistance (hyg) gene (to select for chromosomal integration) which was removed after each targeting event by Cre-mediated recombination between the loxP sites (open circles) flanking the hyg genes. The alleles are indicated with an H in cases in which they contain a hyg gene (SH, 129/S2neo-hyg; PH, BALB/c/Pneo-hyg) and without an H in cases in which the hyg gene has been removed (S, 129/S2neo; P, BALB/c/Pneo). Removal of the hyg gene was confirmed by Southern blotting (using the neo probe fragment depicted in the diagram) with a StuI/HindIII digest of genomic DNA. Using the indicated StuI and HindIII polymorphisms, this analysis also confirms linkage of the S2neo gene to the 129 allele. Southern blot signals for cell lines with the genotypes SH/+, S/+, S/PH, and S/P, where + indicates the nontargeted allele, are shown. St, StuI; P, PacI; HIII, HindIII; N, NcoI, RI, EcoRI, Ea, EagI.

Using targeting fragments derived from the cognate strains (51), we targeted the S2neo gene to an intron of the Rb locus on the 129/Sv-derived chromosome 14 (S allele) and the Pneo gene to the BALB/c-derived chromosome 14 at the same position (P allele) (Fig. 1A). We consecutively targeted both alleles by using a linked hygromycin resistance gene (hyg), giving rise to the intermediate SH and PH alleles (Fig. 1B). The hyg gene was removed stepwise after each targeting event by Cre-mediated recombination between the loxP sites which flank the hyg gene (22), generating the S and P alleles. Based upon this design, the homologous chromosomes in the S/P cell line differ from each other only by the mutations in the neo genes and the strain-specific polymorphisms flanking the neo genes.

Allelic recombination is strongly induced by a DSB but is 1,000-fold less efficient than nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ).

We tested the efficiency of DSB-induced recombination at the neo genes in the S/P cell line by transfecting an I-SceI expression vector and selecting for allelic recombinants with G418. G418-resistant colonies arose at a frequency of 4.6 × 10−5 ± 1.5 × 10−5 relative to the number of cells surviving transfection. This frequency of allelic recombination is similar to that of a previous measure of allelic recombination in an isogenic ES cell line (43), although it is significantly lower than that of intrachromosomal recombination (36, 39). In contrast, no G418-resistant clones arose from untransfected cells (<3.7 × 10−7), indicating that spontaneous recombination at allelic positions is extremely rare.

To verify that the G418-resistant clones were the result of allelic recombination, we tested whether the I-SceI site in the S allele was converted to an NcoI site, which is the wild-type neo sequence at this position in the P allele (Fig. 2A). The neo genes from both alleles were amplified from genomic DNA of 29 individual G418-resistant colonies by using non-allele-specific primers (rb1 and p6−), and the amplified product was cleaved with either I-SceI or NcoI (Fig. 2B). We found that the amplified products of all 29 G418-resistant clones were completely cleaved by NcoI but not at all by I-SceI. This contrasts with the amplified product of the parental S/P cell line, which was approximately half cleaved by each of I-SceI and I-NcoI. Thus, the G418-resistant clones are derived from DSB repair of the S allele by allelic recombination using the P allele as the template, resulting in homozygosity at the DSB site.

FIG. 2.

DSB repair by allelic recombination and by NHEJ. (A) A DSB generated in the S2neo gene by the I-SceI endonuclease can be repaired by mechanisms that result in loss of the I-SceI site, as shown in the diagram. Repair of the DSB by allelic recombination, using the Pneo allele as a template for repair, results in replacement of the I-SceI site with an NcoI site and creation of a wild-type neo gene. Alternatively, repair of the DSB can occur by NHEJ, resulting in insertions (+) or deletions (Δ) at the I-SceI site. After the primers indicated by the arrows were used for PCR amplification of the S2neo gene, digestion of the PCR product by I-SceI and NcoI and resolution of the products on an agarose gel along with uncut product were performed and alterations to the I-SceI site as a consequence of DSB repair were analyzed. (B) In G418-resistant recombinants, the I-SceI site has been converted into an NcoI site. The PCR products of the rb1 and p6− primer set for the parental cell line (S/P) and a G418-resistant allelic recombinant arising from expression of I-SceI (R) are shown. S, I-SceI; N, NcoI; U, uncut product. (C) Quantification of total loss of the I-SceI site. The PCR products of the rb1 and p6+ primer set for the parental cell line prior to I-SceI transfection or on the 5th day of growth in nonselective media after I-SceI transfection are shown. The faint I-SceI-resistant fragment observed from the I-SceI transfected cells (but not from the S/P cells) is approximately 5% of the total amplification product.

In addition to HDR, DSBs can also be repaired by NHEJ, which leads to deletions or insertions at the DSB site, in this case resulting in loss of the I-SceI cleavage site (17). To compare the efficiency of NHEJ with that of recombination between the neo alleles, we isolated genomic DNA from the total cell population that was transfected with the I-SceI expression vector. In this case, we amplified the neo gene of the S allele using an allele-specific primer (p6+), which anneals to the 6-bp insertion that is present on the S allele but is absent from the P allele, and then cleaved the amplified product with I-SceI (Fig. 2C). From multiple independent transfections, we found that approximately 5% of amplified product from the transfected cell population was resistant to cleavage by I-SceI, which was indicative of NHEJ, whereas the product from untransfected cells was completely cleaved by I-SceI. This frequency of NHEJ is similar to previous measures of I-SceI-induced NHEJ in direct-repeat recombination experiments (39, 49). It should be noted that this measure of NHEJ is likely to be an underestimate of total end joining, since it does not include precise events which restore the I-SceI site. Thus, an I-SceI-induced DSB is repaired at least 1,000-fold more efficiently by NHEJ than by allelic recombination (5 × 10−2 versus 4.6 × 10−5, respectively).

LOH is generally limited to the vicinity of the DSB.

To determine whether LOH extends beyond the immediate vicinity of the break site, we analyzed recombinants for markers that are heterozygous between the P and S alleles in the parental cell line. We began by assaying the genotypes of four heterozygous markers located downstream of the I-SceI site which are at the end of the neo gene and within the Rb locus itself (Fig. 3A). H3, the heterozygous marker closest to the DSB, is a HindIII restriction site polymorphism 0.3 kb from the DSB which is present on the P allele (H3+) but absent from the S allele (H3−). To test the genotype of the H3 marker in individual recombinants, we used non-allele-specific primers (rb1 and p6−) to amplify the neo genes of the S and P alleles and cleaved the amplified product with HindIII (Fig. 3B). From 162 individual recombinants, we found that 145 gave an amplified product that, like the parental S/P cells, was approximately half cleaved by HindIII, indicating that these recombinants contain both the H3+ and H3− polymorphisms (e.g., recombinant R1) (Fig. 3B). Thus, the majority of recombinants maintained heterozygosity 0.3 kb from the DSB site. In 17 of the 162 recombinants (10.5%), however, the amplified product was completely cleaved by HindIII (e.g., recombinant R2), indicating that these recombinants contain only the H3+ polymorphism. Thus, these recombinants exhibit LOH extending at least 0.3 kb from the DSB site (Fig. 4).

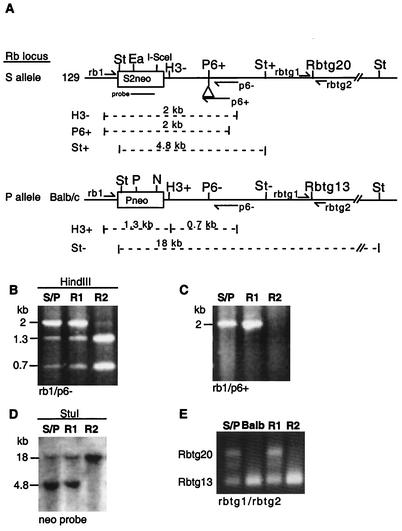

FIG. 3.

Repair of a DSB by allelic recombination can result in LOH of markers within 6 kb of the DSB. (A) Individual recombinants were analyzed for LOH of four polymorphic markers located within 6 kb downstream of the DSB. The positions of PCR primers and sizes of restriction fragments used in analyzing the genotypes of these markers are shown. (B) LOH of the H3 marker, a HindIII restriction site unique to the P allele, was analyzed by PCR amplification of the neo genes of both alleles using the primers rb1 and p6−, followed by digestion of the amplified product with HindIII and resolution on an agarose gel. The HindIII-resistant (2 kb) and -cleaved (1.3 and 0.7 kb) products for each of three cell types are shown: S/P, the parental cell line; R1, a recombinant clone without LOH of the given marker; R2, a recombinant clone with LOH of the marker. (C) LOH of the P6 marker, an insertion of 6 bp unique to the S allele, was analyzed by PCR using the primers rb1 and p6+, which specifically amplify an allele containing the 6-bp insertion. The products, as resolved on an agarose gel for the three cell types described for panel B, are shown. Definitions of abbreviations are the same as those for panel B. (D) LOH of the St marker, a StuI restriction site unique to the S allele, was analyzed by Southern blotting of genomic DNA digested with StuI and probed with a fragment of the neo gene. The Southern blotting signals for the St− (18 kb) and St+ (4.8 kb) polymorphisms for the three cell types described for panel B are shown. Definitions of abbreviations are the same as those for panel B. (E) LOH of the Rbtg marker, an insertion of seven TG repeats in the S allele (Rbtg20) relative to the P allele (Rbtg13), was analyzed by PCR amplification using the rbtg1 and rbtg2 primers, which flank the repeats. The Rbtg13 and Rbtg20 products resolved on a high-percentage agarose gel for the three cell types described for panel B, along with the product from genomic DNA isolated from a BALB/c mouse, are shown. Other definitions of abbreviations are the same as those for panel B.

FIG. 4.

LOH of markers is continuous along the length of a chromosome but decreases in frequency as the distance between the marker and the DSB increases. The genotypes of 162 individual recombinants were analyzed as described for Fig. 3 for LOH of markers within the Rb locus. All recombinants were analyzed for LOH of the two markers closest to the DSB, i.e., H3 and P6. Subsequently, the 17 recombinants with LOH at the H3 marker and an additional 15 recombinants that maintained heterozygosity at H3 were analyzed for LOH at the St and Rbtg markers. The numbers of individual recombinants belonging to each genotype are shown. Also shown for each marker is its distance from the DSB, along with the overall percentages of recombinants whose genotypes include LOH of this marker.

We next analyzed the P6 marker, which is 1 kb downstream from the DSB. This marker contains the 6-bp insertion on the S allele (P6+) which is absent from the P allele (P6−). Loss of the P6+ polymorphism from the repaired S allele chromosome was tested by PCR using the p6+ primer, which specifically anneals to the 6-bp insertion (Fig. 3C). The majority of the 162 recombinants, like the parental S/P cells, gave this P6+-specific amplification product (e.g., recombinant R1) (Fig. 3B). However, nine recombinants (5.5%) did not give this amplified product and thus exhibited loss of the P6+ polymorphism. Interestingly, each of the nine recombinants that exhibited LOH at the P6 marker also exhibited LOH at the H3 marker such that the LOH tract was continuous (Fig. 4). These results indicate that there is a small class of recombinants in which LOH extends at least 1 kb from the DSB (Fig. 4).

We also examined LOH of two additional markers in the Rb locus. We analyzed these markers in all 17 recombinants that exhibited LOH at the H3 marker as well as in 15 of the 145 recombinants that did not. The first of these two markers, St, is located 4 kb from the DSB and is a StuI restriction site polymorphism which is present on the S allele (St+) but is absent from the P allele (St−). The genotype of this marker was tested by Southern blot analysis using a neo gene fragment as probe for detection of genomic DNA cleaved with StuI (Fig. 3A and D). The other marker, Rbtg, located 6 kb from the DSB, is a TG-repeat polymorphism, with 20 TG repeats on the S allele (Rbtg20) and 13 TG repeats on the P allele (Rbtg13). The genotype of this marker was analyzed by PCR using primers that flank the repeats (rbtg1 and rbtg2), followed by separation of the amplified products on high-percentage agarose gels (Fig. 3A and E). We found that the StuI restriction site was lost in 4 of the 32 analyzed recombinants and that the Rbtg20 polymorphism was lost in 3 of the 32 recombinants (Fig. 4). All four recombinants with LOH at the St marker also have LOH at the H3 and P6 markers, and all three recombinants with LOH at the Rbtg marker also have LOH at the St, H3, and P6 markers. Thus, LOH of a distal marker in recombinants is accompanied by LOH of more-proximal markers in the interval to the DSB site such that the LOH tracts are continuous. The analysis indicates that a small percentage of the overall recombinants (1.9%) exhibit LOH of markers extending at least 6 kb from the DSB.

Heterozygosity is maintained in allelic recombinants at markers ≥1 cM from the DSB.

While we recovered recombinants in which LOH extended at least several kilobases, it was not clear whether LOH extended to loci significantly more distant from the DSB and thus whether these recombinants underwent a substantial loss of allele-specific information along the chromosome arm. To test this, we examined three SSLP markers consisting of TG-repeat-length polymorphisms between the 129/Sv and BALB/c strains. These markers are located 1 and 13 cM telomeric (D14Mit224 and D14Mit95, respectively) and 1 cM centromeric (D14Mit160) to the Rb locus, from a total chromosome 14 genetic length of 69.9 cM (Fig. 5) (4).

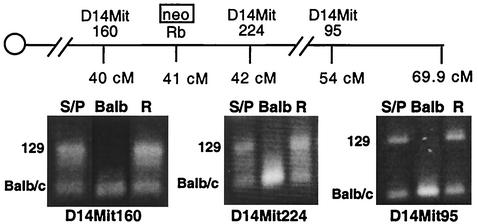

FIG. 5.

Repair of a DSB by allelic recombination does not result in detectable levels of LOH of markers located ≥1 cM from the DSB. The genotypes of the chromosome 14 SSLP markers D14Mit160, D14Mit224, and D14Mit95 were analyzed by PCR amplification using primers that flank each polymorphism and resolution of the products on high-percentage agarose gels. The genotypes of the D14Mit160 and D14Mit224 markers were determined for 160 recombinants. The genotype of the D14Mit95 marker was determined for the 17 recombinants with LOH at the H3 marker and for an additional 15 recombinants without LOH at this marker. The amplified products for the 129 and BALB/c alleles are indicated. S/P, parental cell line; BALB, BALB/c mouse; R, a representative recombinant clone.

The genotypes of these markers were determined by PCR analysis using primers that flank the repeats, followed by separation of the amplified products on high-percentage agarose gels. We tested the genotypes of the D14Mit224 and D14Mit160 markers in a total of 160 recombinants, including all those that exhibited LOH of the H3 and Rbtg markers. We found that all recombinants retained both the 129/Sv and BALB/c polymorphisms for both of these SSLP markers (recombinant R) (Fig. 5). We also analyzed the genotype of the more-distal marker, D14Mit95, in a subset of these recombinants, namely, the 32 recombinants that were previously tested for LOH at the St and Rbtg markers. We found that all 32 recombinants also retained both the 129/Sv and BALB/c polymorphisms for this marker. These results indicate that DSB-induced allelic recombination does not result in detectable levels of LOH at loci located 1 cM or further from the DSB. Thus, extensive LOH is generally suppressed during DSB-induced recombination between homologous chromosomes. Considering that we have examined 160 recombinants, LOH extending ≥1 cM occurs in <0.6% of recombination events.

Crossing over between homologous chromosomes was not detected during DSB-induced allelic recombination.

Crossing over between homologous chromosomes is a frequent outcome of DSB-induced allelic recombination during meiosis (5, 50). Although we did not recover recombinants with LOH extending the length of a chromosome arm, which can be indicative of S/G2 exchange events (see Fig. 7), it was still possible that crossing over occurred without generating extensive LOH. To test for crossing over in our DSB-induced allelic recombinants, we assayed the linkage of a marker upstream of the DSB site to markers downstream of the DSB site. To establish an altered linkage relationship, this analysis requires that the tested markers are heterozygous in the recombinants. Upstream of the DSB is the Ea/P marker, which is an EagI restriction site in the S2neo gene of the S allele but a PacI site in the Pneo gene of the P allele. G418 selection requires an EagI site to be retained in the neo+ allele; however, the PacI site would also be expected to be retained in the Pneo gene, since it is on the P allele, the donor of genetic information which does not undergo a DSB. We tested for the retention of the PacI site in 80 recombinants by amplifying the neo genes using non-allele-specific primers (ep1 and ep2) and then cleaving the amplified product with PacI. As expected, the amplified product was approximately half cleaved by PacI in all 80 recombinants tested (data not shown), indicating a retention of heterozygosity at this site.

FIG. 7.

Extensive LOH resulting from allelic recombination can be suppressed at a number of steps. The overall frequency of allelic recombination can be suppressed by decreasing either the frequency of DSB formation (i) or the efficiency of strand invasion of a broken end into the homologous chromosome (ii). Strand invasion results in D-loop formation and priming of DNA synthesis, as shown. Normally this intermediate would be converted to a product with short regions of LOH by joining of the nascent strand, after minimal DNA synthesis, to the other side of the DSB (data not shown). However, this D-loop intermediate can instead be processed into either of two pathways that result in extensive LOH. (A) LOH by crossing over. In this pathway, the D-loop intermediate is converted to a double Holliday junction, which can be resolved to a crossover product (as shown) or a noncrossover product (data not shown). Thus, crossing over may normally be suppressed by inhibiting Holliday junction formation (iii) or resolution to a crossover product (iv). LOH by crossing over requires that the recombinant chromatids segregate into separate daughter cells. It is formally possibly that this step is suppressed as well (v), such that recombinant chromatids would instead cosegregate into the same daughter cell. However, a recent study suggests that recombinant chromatids can segregate away from each other at detectable frequencies (28). (B) LOH by break-induced replication. In this pathway, the D-loop intermediate persists and migrates to the end of the chromosome arm as a result of extensive leading-strand synthesis. Lagging-strand synthesis results in replication of the noninvading strand. The other end of the chromosome arm is lost during this process. Thus, LOH by break-induced replication can be suppressed by inhibiting either extensive replication (vi) or loss of a chromosome arm (vii).

Two downstream markers (P6 and St) were used to test for crossing over in two different intervals, namely, the interval between the DSB site and the P6 marker (interval co1) and the interval between the P6 and St markers (interval co2) (Fig. 6A). A crossover in interval co1 would disrupt the linkage of the P6+ polymorphism with the EagI site, both of which are on the S allele in the parental S/P cell line (Fig. 6B). We tested for this in all 153 recombinants that maintained heterozygosity at the P6 marker by amplifying the neo gene linked to the P6+ polymorphism (primers rb1 and p6+) and then cleaving the amplified product with EagI. We found that the amplified product was cleaved by EagI in all of the recombinants, as was the amplified product in the parental S/P cell line. Therefore, none of these 153 recombinants showed an altered linkage relationship for the Ea/P and P6 markers; that is, there was no evidence of crossing over in interval co1.

FIG. 6.

Repair of a DSB by allelic recombination does not result in detectable levels of crossing over between alleles. (A) Two potential crossover intervals are indicated: co1, positioned between the DSB and the P6 marker, and co2, positioned between the P6 and St markers. (B) Recombinants were analyzed for a crossover in interval co1, which would establish a new linkage of the P6+ polymorphism of the S allele to the PacI restriction site polymorphism of the P allele, as shown in the diagram. This novel linkage was assayed for by PCR amplification using the primers rb1 and p6+, the latter of which specifically amplifies alleles containing the P6+ polymorphism, followed by cleavage of the product by EagI (Ea) or PacI (P) and resolution of the products on an agarose gel along with uncut product (U). The products from the parental cell line (S/P) and a representative recombinant clone (R) are shown. None of the recombinants showed this novel linkage. (C) Recombinants with LOH at the p6 marker, but not the St marker, were analyzed for the product of a crossover in interval co2, which would establish a novel linkage of the StuI restriction site polymorphism of the S allele to the PacI restriction site polymorphism of the P allele, as shown in the diagram. Assays to detect the presence of this novel linkage were performed by PCR amplification of the neo gene from the 4- to 5-kb size-enriched StuI fragments from genomic DNA. The neo genes were amplified using the primers ep1 and ep2, and the products were subsequently digested by EagI (Ea) or PacI (P) and resolved on an agarose gel along with uncut product (U). The products from the size-enriched genomic DNA (StuI; 4- to 5-kb size selected) derived from the parental cell line (S/P) and a clone (R) which is representative of the recombinants tested for this novel linkage are shown. Also shown are the products from the total genomic DNA of the parental cell line.

The remaining nine recombinants had undergone LOH at the P6 marker but maintained heterozygosity at the distal D14Mit224 marker and therefore might have undergone crossing over in intervals in between these two markers. Of these, five maintained heterozygosity at the St and downstream markers, such that crossing over might have occurred in the interval between P6 and St. Crossing over in this co2 interval would link the St+ polymorphism from the S allele to the PacI polymorphism from the P allele (Fig. 6C).

To test for this new linkage relationship in these five recombinants, we first enriched for the neo gene from the chromosome containing the St+ polymorphism by digesting genomic DNA with StuI and then isolating genomic DNA between 4 and 5 kb in size, in the size range of the allele containing the StuI restriction site (4.8 kb). Subsequently, the neo gene contained in this size-enriched fraction was amplified and then cleaved with either EagI or PacI (Fig. 6C). In each of these five recombinants, as well as the S/P cell line, the amplified product from this size-enriched genomic DNA was substantially cleaved by EagI but only slightly cleaved by PacI. The lack of complete EagI cleavage and the slight cleavage by PacI is likely due to a small amount of the larger StuI fragment from the other allele contaminating the size-enriched fragment. This contrasts with the amplified product generated from the non-size-selected genomic DNA, which was cleaved equally well by both EagI and PacI. Thus, none of these five recombinants exhibited a novel linkage of the St marker to the PacI site, implying that crossing over did not occur between the DSB site and St marker. As LOH terminated within the co2 interval in these recombinants, the generation of LOH does not appear to be associated with crossing over.

In summary, we found that 158 of 162 recombinants had not undergone crossing over during DSB-induced allelic recombination. We could not determine whether crossing over had occurred for the remaining four recombinants, because they had undergone LOH at the St marker, the marker furthest downstream of the DSB site that could be linked with the upstream PacI site. Thus, allelic recombination involving homologous chromosomes is associated with crossing over in ≤2.5% of recombinants.

DISCUSSION

Mitotic recombination between homologous chromosomes has been inferred to be a major pathway leading to the allele-specific loss of information (LOH) commonly found in tumor cells. In the present study, we found that a DSB stimulates recombination between homologous chromosomes in mouse ES cells at least 100-fold. These HDR events are still a minor fraction of total DSB repair events, however, with NHEJ estimated to be another 3 orders of magnitude higher. Although we were unable to directly measure DSB-induced sister-chromatid recombination (because the sister chromatids are identical), the expectation is that it would also be significantly more frequent than HDR between homologous chromosomes. This expectation is based on the high frequency of intrachromosomal recombination between nearby repeats (∼2 × 10−2) (34, 39), which at least in part reflects repair from a sister chromatid (19).

Importantly, although recombination between homologous chromosomes was highly induced by a DSB, we determined that it does not result in extensive LOH, indicating that such repair is not inherently genome destabilizing. We found that the majority of recombinants had LOH limited to the immediate vicinity of the DSB, with a minor class of recombinants (1.9%) exhibiting LOH extending ≥6 kb. Furthermore, we found no evidence for LOH at markers 1 cM or further from the DSB site, and crossing over was not observed in any of the 158 informative recombinants.

Despite the large induction of recombination by a single DSB, the lack of extensive LOH formation raises the possibility that a different initiating event is required. For example, two DSBs, one on each homologous chromosome, might result in extensive LOH by leading to chromosomal exchange, through repair mechanisms other than HDR, by analogy to the repair of two DSBs on heterologous chromosomes that leads to translocation chromosomes (42). However, such an exchange event between homologous chromosomes would only produce LOH if it occurred after DNA replication followed by segregation of the exchanged chromatids to distinct daughter cells during mitosis. The presence of two simultaneous DSBs at the same or nearby positions on homologous chromosomes would be expected to be a rare event; however, fragile site usage may increase their frequency at certain genomic positions (41). Alternatively, the initiating lesion might have a different structure. For example, I-SceI-induced breaks might not have a structure representative of all spontaneous or damage-induced DSBs. Furthermore, one-ended DSBs, which differ from the two-ended I-SceI-generated DSBs, have been proposed to form during DNA replication as a result of replication fork impediments (10). Recent studies suggest that repair of one-ended DSBs and repair of two-ended DSBs have different genetic requirements and possibly different outcomes (39; see also reference 11), supporting a possible role for these lesions (although as yet this is speculative).

Given the strong induction of recombination, however, repair of a single two-ended DSB by HDR may nevertheless be an initiating event for extensive LOH under some circumstances. Possibly, extensive LOH occurs in wild-type cells at low frequency. Alternatively, extensive LOH might normally be suppressed but disruptions in the normal repair process might promote its formation.

Suppression of crossing over and break-induced replication during mitotic recombination.

Evidence that mitotic recombination is a major pathway leading to LOH has primarily come from polymorphic marker analysis and karyotyping of tumor cells as well as the examination of LOH in model systems, including hybrids of inbred mouse strains (18, 25, 46). Two intact homologous chromosomes were observed, yet only a portion of the chromosomes maintained heterozygosity for polymorphic markers. While breakpoints have not been sequenced to verify that these events arose from homologous recombination, the recombinant chromosomes are best explained as having arisen from homologous recombination by either of two pathways. The recombinant chromosomes might be the product of crossover recombination involving replicated parental chromosomes, with the recombinant chromatids segregating away from each other into separate daughter cells (Fig. 7A). Alternatively, extensive gene conversion by a process known as break-induced replication also might result in LOH (Fig. 7B).

During meiosis, crossing over between replicated homologous chromosomes is strongly stimulated by DSBs such that in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, for which DSB repair has been well characterized at the molecular level, one-third or more of recombination events are associated with crossing over (5, 20, 38). In mammalian meioses, a substantial fraction of events are likely to be associated with crossing over as well (2, 3, 30, 33). While meiotic DSBs are normally introduced by the Spo11 transesterase, an exogenous DSB formed by the HO endonuclease which produces the same DNA end structure as I-SceI similarly promotes a high frequency of crossing over (32). Although crossing over between homologs during mitotic DSB repair in yeast is severalfold less frequent than during meiosis, it is still readily detected (i.e., fourfold in one study [32; see also reference 31]). Thus, the lack of observed crossing over in the recombinants characterized here suggests a strong suppression of crossing over that contrasts not only with recombination during meiosis but also with recombination during mitotic recombination in yeast.

A lack of an association of HDR with crossing over has previously been reported in mammalian cells in events involving sequence repeats on sister chromatids and heterologs (19, 43). In both of these previous studies, however, recombination was assayed between relatively short repeats, and in yeast, crossing over appears to depend on a minimal threshold length of homology (16). In the experiments presented here, homology extends along the entire length of the chromosome, ruling out limitations of homology length as a reason for suppressed crossing over. For a small fraction of recombinants with extensive gene conversion, we could not eliminate the possibility that crossing over had occurred. Nevertheless, crossover suppression appears to be a common feature of HDR events involving any type of homologous recombination partners in mammalian cells, possibly to prevent LOH and other types of genomic alterations. A recent study of spontaneously arising allelic recombinants (for which the initiating lesion is unknown) also found a lack of events associated with crossing over, indicating that suppression of crossing over may also occur during the repair of lesions other than DSBs or that a DSB may be the initiating lesion of these spontaneous events as well (40).

An alternative pathway to crossing over that might produce recombinant chromosomes of the sort found in tumor cells and in model systems is break-induced replication (Fig. 7B). In this pathway, which was identified in yeast, a broken chromosome invades the homolog at the allelic position, setting up a replication fork that proceeds to the end of the chromosome (31, 48). Since none of the recombinants presented here exhibit LOH extending to the end of the chromosome, break-induced replication appears to be inefficient in wild-type mammalian cells. However, this pathway was uncovered using yeast recombination mutants, raising the question as to whether such events would be detected in mammalian mutants.

While there is no evidence for break-induced replication during HDR in mammalian cells, the recombinants we recovered are nevertheless consistent with a replication-based recombination mechanism (17, 37, 38), with an allowance for variation in the gene conversion tract length. HDR by this mechanism, often termed synthesis-dependent strand annealing, begins with strand invasion of one end of the DSB into a homologous template to establish a D-loop. As in break-induced replication (Fig. 7B), the invading strand then primes DNA synthesis, which is associated with migration of the D-loop. However, in contrast to break-induced replication, repair synthesis is not extensive and thus does not continue to the end of the chromosome. Instead, the D-loop is disrupted and the nascent strand anneals to the other end of the DSB. Based on this model, LOH of markers distal to the DSB would be the result of DNA synthesis and gene conversion tracts would be continuous, as we have observed, yet heterozygosity would be maintained after the point of annealing to the end of the chromosome.

Therefore, regulation of each of these steps might be important for limiting the conversion of normal repair intermediates into break-induced replication products to produce extensive LOH (Fig. 7B). For example, the participation of the second end in an annealing reaction might be important in limiting the amount of repair synthesis, as might the progression of the replication fork itself. Regulation of certain of these steps may also be important to prevent crossing over, for example, by preventing conversion of intermediates into a Holliday junction which might be resolved in a crossover configuration (Fig. 7A).

Factors important for the suppression of LOH and allelic recombination.

A number of factors, operating by either limiting the frequency of mitotic recombination events themselves or restricting the extent of LOH during mitotic recombination, may therefore be required to efficiently suppress LOH by mitotic recombination. The BLM helicase likely plays a major role in this suppression, as BLM mutation leads to an increased frequency of LOH in humans and mice (13, 14, 24, 29). Since BLM mutants also show a high frequency of sister chromatid exchange (13), it is possible that the biochemical activity of BLM in general prevents a crossover outcome to recombination events.

It is also conceivable that LOH is affected by the balance of factors in different cell types. Wild-type ES cells have been found to undergo spontaneous, extensive LOH (26). However, other studies provide somewhat conflicting data about cell type differences and the generation of LOH. In one study, LOH was shown to occur in ES cells at a 10-fold higher frequency than in a somatic cell type (i.e., T cells) (53), whereas in a second study which examined the same locus, LOH (including that induced by mitotic recombination) was substantially less frequent in ES cells compared with both T cells and embryonic fibroblasts (6, 47). It is not clear whether the cell type differences in mitotic recombination are accounted for by an overall difference in the frequency of recombination events between homologous chromosomes or whether the outcome of recombination events was altered.

Two other factors that have been shown to affect LOH are sequence heterology and DNA methylation. ES cells with hypomethylated DNA from Dnmt1 deficiency have elevated rates of LOH (7). Although much of the increase appears to be from a nondisjunction mechanism, LOH arising from mitotic recombination may also be somewhat elevated. As with the cell type differences, it is not clear whether the elevation is due to an overall increased frequency of recombination or an alteration in the outcome of recombination events. Interestingly, some solid tumors, which frequently exhibit a high degree of genomic instability, have been characterized by a global genome hypomethylation (23).

Not surprisingly, LOH arising from mitotic recombination appears to be strongly suppressed by substantial sequence heterology. Mitotic recombination events leading to LOH are readily detected in cells from F1 hybrid mice derived from inbred mouse strains (47). However, such LOH events do not occur in F1 hybrid mice derived from interspecific crosses (Mus musculus and Mus spretus). The degree of heterology apparently also affects meiotic progression, as the F1 hybrid males from the interspecific cross are sterile (9). That sequence heterology affects the frequency of recombination in both yeast and mammalian cells, including DSB-induced events, is well established (e.g., see references 8 and 12 and references therein). Thus, the reduction in LOH events recovered from the interspecific crosses may simply reflect a reduced level of recombination, although it is possible that there is also an effect on the extent of LOH.

The approach that we have developed to induce mitotic recombination between chromosome homologs and to examine the extent of LOH should allow an assessment of the specific roles of these and other factors in the suppression of extensive LOH during HDR.

Acknowledgments

We thank Rudolf Jaenisch (Cambridge, Mass.) and John Schimenti (Bar Harbor, Maine) for the v17.2 ES cell line and Hein te Riele (Amsterdam, The Netherlands) for the Rb targeting fragments.

J.M.S. is supported by American Cancer Society postdoctoral fellowship PF-00-106-01-MGO. This work was supported in part by National Science Foundation grant MCB-9728333 (M.J.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Araki, K., M. Araki, J. Miyazaki, and P. Vassalli. 1995. Site-specific recombination of a transgene in fertilized eggs by transient expression of Cre recombinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:160-164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barlow, A. L., F. E. Benson, S. C. West, and M. A. Hulten. 1997. Distribution of the Rad51 recombinase in human and mouse spermatocytes. EMBO J. 16:5207-5215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barlow, A. L., and M. A. Hulten. 1998. Crossing over analysis at pachytene in man. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 6:350-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blake, J. A., J. E. Richardson, C. J. Bult, J. A. Kadin, and J. T. Eppig. 2002. The Mouse Genome Database (MGD): the model organism database for the laboratory mouse. Nucleic Acids Res. 30:113-115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cao, L., E. Alani, and N. Kleckner. 1990. A pathway for generation and processing of double-strand breaks during meiotic recombination in S. cerevisiae. Cell 61:1089-1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cervantes, R. B., J. R. Stringer, C. Shao, J. A. Tischfield, and P. J. Stambrook. 2002. Embryonic stem cells and somatic cells differ in mutation frequency and type. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:3586-3590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen, R. Z., U. Pettersson, C. Beard, L. Jackson-Grusby, and R. Jaenisch. 1998. DNA hypomethylation leads to elevated mutation rates. Nature 395:89-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen, W., and S. Jinks-Robertson. 1999. The role of the mismatch repair machinery in regulating mitotic and meiotic recombination between diverged sequences in yeast. Genetics 151:1299-1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Copeland, N. G., N. A. Jenkins, D. J. Gilbert, J. T. Eppig, L. J. Maltais, J. C. Miller, W. F. Dietrich, A. Weaver, S. E. Lincoln, R. G. Steen, et al. 1993. A genetic linkage map of the mouse: current applications and future prospects. Science 262:57-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cox, M. M., M. F. Goodman, K. N. Kreuzer, D. J. Sherratt, S. J. Sandler, and K. J. Marians. 2000. The importance of repairing stalled replication forks. Nature 404:37-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cromie, G. A., J. C. Connelly, and D. R. Leach. 2001. Recombination at double-strand breaks and DNA ends: conserved mechanisms from phage to humans. Mol. Cell 8:1163-1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elliott, B., and M. Jasin. 2001. Repair of double-strand breaks by homologous recombination in mismatch repair-defective mammalian cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:2671-2682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ellis, N. A., D. J. Lennon, M. Proytcheva, B. Alhadeff, E. E. Henderson, and J. German. 1995. Somatic intragenic recombination within the mutated locus BLM can correct the high sister-chromatid exchange phenotype of Bloom syndrome cells. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 57:1019-1027. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Groden, J., Y. Nakamura, and J. German. 1990. Molecular evidence that homologous recombination occurs in proliferating human somatic cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:4315-4319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hagstrom, S. A., and T. P. Dryja. 1999. Mitotic recombination map of 13cen-13q14 derived from an investigation of loss of heterozygosity in retinoblastomas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:2952-2957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inbar, O., B. Liefshitz, G. Bitan, and M. Kupiec. 2000. The relationship between homology length and crossing over during the repair of a broken chromosome. J. Biol. Chem. 275:30833-30838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jasin, M. 2001. Double-strand break repair and homologous recombination in mammalian cells, p. 207-235. In J. A. Nickoloff and M. F. Hoekstra (ed.), DNA damage and repair, vol. 3. Humana Press, Totowa, N.J.

- 18.Jasin, M. 2000. LOH and mitotic recombination, p. 191-209. In M. Ehrlich (ed.), DNA alterations in cancer. Eaton Publishing, Natick, Mass.

- 19.Johnson, R. D., and M. Jasin. 2000. Sister chromatid gene conversion is a prominent double-strand break repair pathway in mammalian cells. EMBO J. 19:3398-3407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keeney, S. 2001. Mechanism and control of meiotic recombination initiation. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 52:1-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keeney, S., F. Baudat, M. Angeles, Z. H. Zhou, N. G. Copeland, N. A. Jenkins, K. Manova, and M. Jasin. 1999. A mouse homolog of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae meiotic recombination DNA transesterase Spo11p. Genomics 61:170-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kilby, N. J., M. R. Snaith, and J. A. Murray. 1993. Site-specific recombinases: tools for genome engineering. Trends Genet. 9:413-421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laird, P. W., and R. Jaenisch. 1996. The role of DNA methylation in cancer genetic and epigenetics. Annu. Rev. Genet. 30:441-464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Langlois, R. G., W. L. Bigbee, R. H. Jensen, and J. German. 1989. Evidence for increased in vivo mutation and somatic recombination in Bloom's syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:670-674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lasko, D., W. Cavenee, and M. Nordenskjold. 1991. Loss of constitutional heterozygosity in human cancer. Annu. Rev. Genet. 25:281-314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lefebvre, L., N. Dionne, J. Karaskova, J. A. Squire, and A. Nagy. 2001. Selection for transgene homozygosity in embryonic stem cells results in extensive loss of heterozygosity. Nat. Genet. 27:257-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lindblad-Toh, K., E. Winchester, M. J. Daly, D. G. Wang, J. N. Hirschhorn, J. P. Laviolette, K. Ardlie, D. E. Reich, E. Robinson, P. Sklar, N. Shah, D. Thomas, J. B. Fan, T. Gingeras, J. Warrington, N. Patil, T. J. Hudson, and E. S. Lander. 2000. Large-scale discovery and genotyping of single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the mouse. Nat. Genet. 24:381-386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu, P., N. A. Jenkins, and N. G. Copeland. 2002. Efficient Cre-loxP-induced mitotic recombination in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nat. Genet. 30:66-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luo, G., I. M. Santoro, L. D. McDaniel, I. Nishijima, M. Mills, H. Youssoufian, H. Vogel, R. A. Schultz, and A. Bradley. 2000. Cancer predisposition caused by elevated mitotic recombination in Bloom mice. Nat. Genet. 26:424-429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lynn, A., K. E. Koehler, L. Judis, E. R. Chan, J. P. Cherry, S. Schwartz, A. Seftel, P. A. Hunt, and T. J. Hassold. 2002. Covariation of synaptonemal complex length and mammalian meiotic exchange rates. Science 296:2222-2225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malkova, A., E. L. Ivanov, and J. E. Haber. 1996. Double-strand break repair in the absence of RAD51 in yeast: a possible role for break-induced DNA replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:7131-7136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Malkova, A., F. Klein, W. Y. Leung, and J. E. Haber. 2000. HO endonuclease-induced recombination in yeast meiosis resembles Spo11-induced events. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:14500-14505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moens, P. B., N. K. Kolas, M. Tarsounas, E. Marcon, P. E. Cohen, and B. Spyropoulos. 2002. The time course and chromosomal localization of recombination-related proteins at meiosis in the mouse are compatible with models that can resolve the early DNA-DNA interactions without reciprocal recombination. J. Cell Sci. 115:1611-1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moynahan, M. E., T. Y. Cui, and M. Jasin. 2001. Homology-directed DNA repair, mitomycin-c resistance, and chromosome stability is restored with correction of a Brca1 mutation. Cancer Res. 61:4842-4850. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moynahan, M. E., and M. Jasin. 1997. Loss of heterozygosity induced by a chromosomal double-strand break. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:8988-8993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moynahan, M. E., A. J. Pierce, and M. Jasin. 2001. BRCA2 is required for homology-directed repair of chromosomal breaks. Mol. Cell 7:263-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nassif, N., J. Penney, S. Pal, W. R. Engels, and G. B. Gloor. 1994. Efficient copying of nonhomologous sequences from ectopic sites via P-element-induced gap repair. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14:1613-1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.PÂques, F., and J. E. Haber. 1999. Multiple pathways of recombination induced by double-strand breaks in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 63:349-404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pierce, A. J., P. Hu, M. Han, N. Ellis, and M. Jasin. 2001. Ku DNA end-binding protein modulates homologous repair of double-strand breaks in mammalian cells. Genes Dev. 15:3237-3242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Quintana, P. J., E. A. Neuwirth, and A. J. Grosovsky. 2001. Interchromosomal gene conversion at an endogenous human cell locus. Genetics 158:757-767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Richards, R. I. 2001. Fragile and unstable chromosomes in cancer: causes and consequences. Trends Genet. 17:339-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Richardson, C., and M. Jasin. 2000. Frequent chromosomal translocations induced by DNA double-strand breaks. Nature 405:697-700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Richardson, C., M. E. Moynahan, and M. Jasin. 1998. Double-strand break repair by interchromosomal recombination: suppression of chromosomal translocations. Genes Dev. 12:3831-3842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Romanienko, P. J., and R. D. Camerini-Otero. 1999. Cloning, characterization, and localization of mouse and human SPO11. Genomics 61:156-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sachidanandam, R., D. Weissman, S. C. Schmidt, J. M. Kakol, L. D. Stein, G. Marth, S. Sherry, J. C. Mullikin, B. J. Mortimore, D. L. Willey, S. E. Hunt, C. G. Cole, P. C. Coggill, C. M. Rice, Z. Ning, J. Rogers, D. R. Bentley, P. Y. Kwok, E. R. Mardis, R. T. Yeh, B. Schultz, L. Cook, R. Davenport, M. Dante, L. Fulton, L. Hillier, R. H. Waterston, J. D. McPherson, B. Gilman, S. Schaffner, W. J. Van Etten, D. Reich, J. Higgins, M. J. Daly, B. Blumenstiel, J. Baldwin, N. Stange-Thomann, M. C. Zody, L. Linton, E. S. Lander, and D. Altshuler. 2001. A map of human genome sequence variation containing 1.42 million single nucleotide polymorphisms. Nature 409:928-933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shao, C., L. Deng, O. Henegariu, L. Liang, N. Raikwar, A. Sahota, P. J. Stambrook, and J. A. Tischfield. 1999. Mitotic recombination produces the majority of recessive fibroblast variants in heterozygous mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:9230-9235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shao, C., P. J. Stambrook, and J. A. Tischfield. 2001. Mitotic recombination is suppressed by chromosomal divergence in hybrids of distantly related mouse strains. Nat. Genet. 28:169-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Signon, L., A. Malkova, M. L. Naylor, H. Klein, and J. E. Haber. 2001. Genetic requirements for RAD51- and RAD54-independent break-induced replication repair of a chromosomal double-strand break. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:2048-2056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stark, J. M., P. Hu, A. J. Pierce, M. E. Moynahan, N. Ellis, and M. Jasin. 2002. ATP hydrolysis by mammalian RAD51 has a key role during homology-directed DNA repair. J. Biol. Chem. 277:20185-20194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Szostak, J. W., T. L. Orr-Weaver, R. J. Rothstein, and F. W. Stahl. 1983. The double-strand-break repair model for recombination. Cell 33:25-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.te Riele, H., E. R. Maandag, and A. Berns. 1992. Highly efficient gene targeting in embryonic stem cells through homologous recombination with isogenic DNA constructs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:5128-5132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thiagalingam, S., S. Laken, J. K. Willson, S. D. Markowitz, K. W. Kinzler, B. Vogelstein, and C. Lengauer. 2001. Mechanisms underlying losses of heterozygosity in human colorectal cancers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:2698-2702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Van Sloun, P. P., S. W. Wijnhoven, H. J. Kool, R. Slater, G. Weeda, A. A. van Zeeland, P. H. Lohman, and H. Vrieling. 1998. Determination of spontaneous loss of heterozygosity mutations in Aprt heterozygous mice. Nucleic Acids Res. 26:4888-4894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.You, Y., R. Bergstrom, M. Klemm, B. Lederman, H. Nelson, C. Ticknor, R. Jaenisch, and J. Schimenti. 1997. Chromosomal deletion complexes in mice by radiation of embryonic stem cells. Nat. Genet. 15:285-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]