Abstract

Eighty-nine penicillin- and ciprofloxacin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates were evaluated by serotyping and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Although penicillin-resistant isolates demonstrated considerable homogeneity, resistance to ciprofloxacin did not correlate with a reduction in genotypic variability. These results suggest that, unlike that of penicillin resistance, the spread of S. pneumoniae ciprofloxacin resistance in Canada is currently not attributable to clonal dissemination.

Clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae with reduced susceptibility to β-lactams and fluoroquinolones may arise de novo or from the clonal spread of one or more resistant strains. Molecular surveillance of penicillin- and multidrug-resistant pneumococci from several countries has demonstrated that, in general, the majority of isolates circulating within a geographic area are derivatives of a relatively small number of clonal lineages (6, 7, 11). Few studies, however, have examined the molecular epidemiology of fluoroquinolone-nonsusceptible S. pneumoniae (1, 4, 10). The purpose of the present study was to compare the genetic relatedness between penicillin- and ciprofloxacin-resistant clinical isolates of S. pneumoniae within Canada.

Eighty-nine clinical isolates of S. pneumoniae were selected from among 1,652 isolates collected between November 1999 and October 2000 as part of an ongoing Canadian Respiratory Organism Susceptibility Study (D. J. Hoban, K. Nichol, L. Palatnick, A. Gin, D. Low, G. G. Zhanel, and The Canadian Respiratory Organism Susceptibility Study Group, Abstr. 41st Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. C2-2102, 2001). Isolates were selected to include all 26 ciprofloxacin-resistant (MIC, ≥4 μg/ml) and all 42 penicillin-resistant (MIC, ≥2 μg/ml) S. pneumoniae isolates collected during this period. Additional isolates of penicillin-susceptible (MIC, ≤0.06 μg/ml), penicillin-intermediate (MIC, 0.12 to 1 μg/ml), and ciprofloxacin-susceptible (MIC, ≤2 μg/ml) S. pneumoniae were also included. Within these last three susceptibility categories, isolates were randomly selected to represent a range of MICs and geographic distributions. Study isolates were collected from 25 medical centers representing major population centers in nine Canadian provinces.

Penicillin and ciprofloxacin susceptibilities were determined by broth microdilution as specified by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS) (12). MIC interpretive standards for penicillin were defined according to the NCCLS breakpoints for 2000 (13). Pneumococci with ciprofloxacin MICs of ≥4 μg/ml were defined as ciprofloxacin nonsusceptible (4).

Isolates were serotyped by the Canadian National Centre for Streptococcus (Edmonton, Alberta) with the use of type-specific antisera (9). Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) was performed as described previously by Louie et al. (8). For the purpose of this study, isolates were defined as genetically indistinguishable, possibly related, or genetically unrelated if their PFGE profiles differed by 0, 1 to 3, or ≥4 bands, respectively. DNA banding patterns were digitized for analysis using Molecular Analyst (Fingerprinting Plus, version 1.12) software and a dendrogram was calculated by the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic averages.

Of the 89 S. pneumoniae study isolates, 27 were penicillin susceptible, 20 were penicillin intermediate, and 42 were penicillin resistant. Twenty-six isolates demonstrated reduced susceptibility to ciprofloxacin, while 63 were ciprofloxacin susceptible. Only three penicillin-resistant and four penicillin-intermediate isolates were coresistant to ciprofloxacin.

Seventeen unique capsular types were identified among the 89 isolates. While the majority of serotypes were identified in a limited number of isolates, predominant serotypes included 9V (19.1%), 14 (15.7%), 19F (15.7%), and 23F (19.1%). Nontypeable strains accounted for 2.2% (2 of 89) of the remaining isolates. Table 1 shows the serotype distribution by penicillin and ciprofloxacin MICs. Penicillin-susceptible and -intermediate S. pneumoniae isolates expressed many different serotypes. High-level penicillin resistance, in comparison, was associated with a particularly limited number of serotypes. Thirty-seven of 42 penicillin-resistant isolates belonged to serotype 9V, 14, 19F, or 23F. This is in contrast to ciprofloxacin resistance, for which 13 serotypes were identified among the 26 ciprofloxacin-nonsusceptible isolates but only 10 different serotypes were identified among the 63 ciprofloxacin-susceptible isolates.

TABLE 1.

Serotype distribution by penicillin and ciprofloxacin MIC

| Serotype | No. of isolates for which the MIC (μg/ml) wasa:

|

Total no. of isolates of serotype | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.03

|

0.06

|

0.12

|

0.25

|

0.5

|

1

|

2

|

4

|

8

|

16

|

32

|

|||||||||||||

| Pen | Cip | Pen | Cip | Pen | Cip | Pen | Cip | Pen | Cip | Pen | Cip | Pen | Cip | Pen | Cip | Pen | Cip | Pen | Cip | Pen | Cip | ||

| 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 6A | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||||||||||||||||

| 6B | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | |||||||||||||

| 8 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 9N | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 9V | 3 | 1 | 2 | 10 | 11 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 17 | ||||||||||||||

| 10A | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 11A | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 14 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 12 | 1 | 2 | 14 | |||||||||||||||

| 15B | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 17F | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 18C | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 19F | 6 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 14 | |||||||||

| 22F | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 23A | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 23F | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 10 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 17 | ||||||||||

| 35B | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | |||||||||||||||||||

| NTb | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Total | 22 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 9 | 5 | 35 | 40 | 9 | 2 | 9 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 7 | 89 |

Pen, penicillin; Cip, ciprofloxacin.

NT, nontypeable.

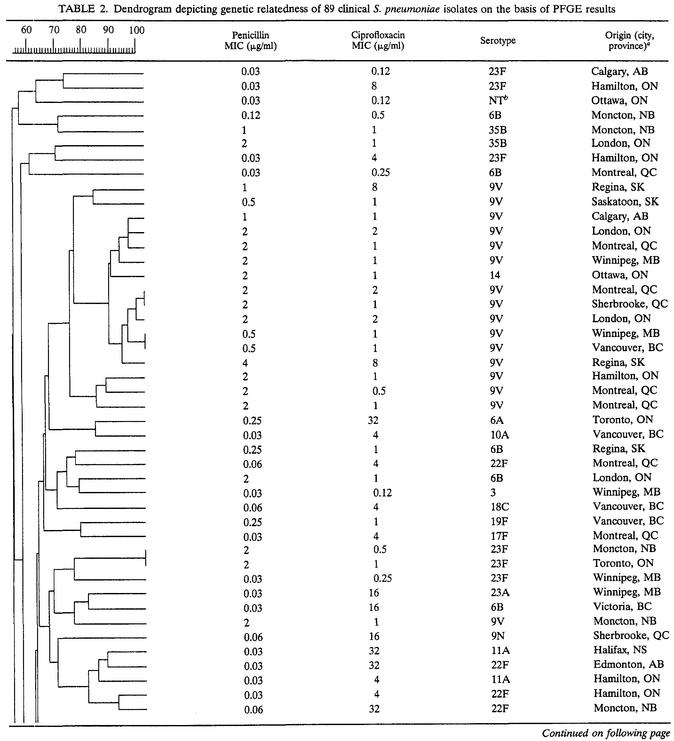

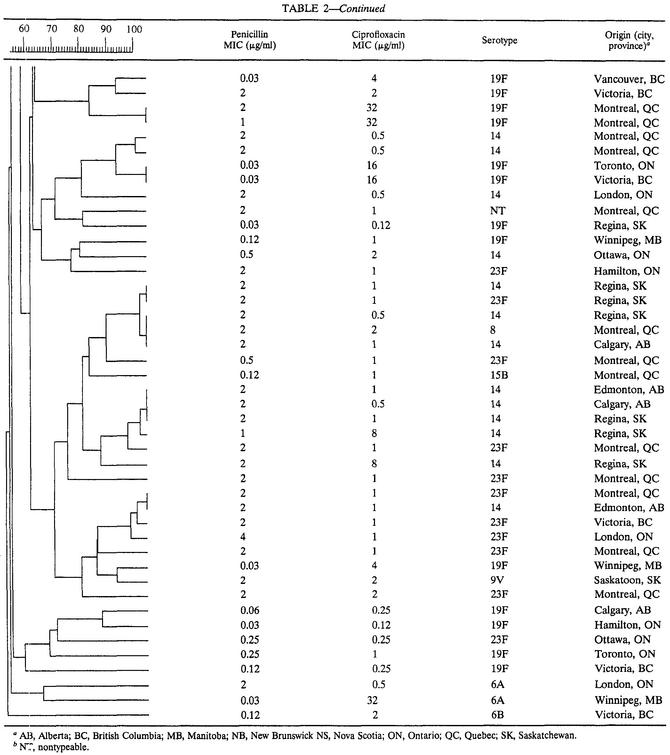

Molecular analysis by PFGE revealed 26 unique genotypes among the 27 penicillin-susceptible isolates and 19 distinct genotypes among the 20 penicillin-intermediate isolates. Penicillin-resistant isolates demonstrated the least heterogeneity, with 34 unique restriction patterns identified among the 42 isolates. Dendrogram analysis identified seven clusters, each containing between two and five isolates, which accounted for 57% (24 of 42) of all penicillin-resistant S. pneumoniae isolates (data not shown). Isolates within these seven clusters belonged to serotypes 9V (2 clusters), 14 (1 cluster), 23F (1 cluster), 14 and 23F (2 clusters), or 8, 14, and 23F (1 cluster). Analysis of PFGE patterns in relation to ciprofloxacin susceptibility revealed 24 distinct PFGE profiles among the 26 isolates with reduced susceptibility to ciprofloxacin. Among the 63 ciprofloxacin-susceptible isolates, 54 unique genotypes were identified. As with the penicillin-resistant isolates, dendrogram analysis revealed seven clusters of genetically related ciprofloxacin-susceptible pneumococci (data not shown).

The overall relatedness among the 89 S. pneumoniae isolates is shown in Table 2. Evaluation of the combined dendrogram revealed 10 epidemiologic clusters (≥90% genetic relatedness), the majority (60%) of which consisted of ciprofloxacin-susceptible, penicillin-resistant isolates (4 clusters) and ciprofloxacin-resistant, penicillin-susceptible isolates (2 clusters). Although some overlap of PFGE types was observed among penicillin-intermediate and penicillin-resistant isolates, no clusters contained penicillin-susceptible and penicillin-resistant isolates concurrently. Minimal overlap of PFGE patterns among ciprofloxacin-susceptible and ciprofloxacin-resistant isolates was observed.

TABLE 2.

Dendrogram depicting genetic relatedness of 89 clinical S. pneumoniae isolates on the basis of PFGE results

AB, Alberta; BC, British Columbia; MB, Manitoba; NB, New Brunswick NS, Nova Scotia; ON, Ontario; QC, Quebec; SK, Saskatchewan.

NT, nontypeable.

In North America, serotypes 4, 6B, 9V, 14, 18C, 19F, and 23F (represented in the heptavalent pneumococcal protein conjugate vaccine formulation) account for more than 80% of invasive pneumococcal disease cases among children and more than 50% of invasive pneumococcal disease cases among adults (5). Asymptomatic individuals frequently carry these same seven serotypes (5). Although penicillin nonsusceptibility has been documented for pneumococcal isolates of several different capsular serotypes, high-level and multidrug resistance is similarly associated with a limited number of serotypes (2). In our study, 88.1% of penicillin-resistant isolates belonged to serotypes 9V, 14, 19F, and 23F. Among this same group of isolates, associations between ciprofloxacin resistance and serotype distribution were not observed. Molecular analysis clearly showed that within a given serotype there may be both conservation and dispersion of genotypes. Similarly, within a given genotype there may be both conservation and dispersion of serotypes. Although the majority of isolates with homogeneous or closely related PFGE patterns were of the same serotype, we also observed a close genetic relatedness among some isolates of serotypes 8, 14, and 23F. Since S. pneumoniae contains only one set of type-specific capsular polysaccharide biosynthesis genes (3), these isolates are thought to be the products of spontaneous in vivo transformation events involving horizontal transfer and recombinational replacement of the genes specifying capsular type (14). It has been hypothesized, therefore, that capsular switching may enable multidrug-resistant phenotypes to spread to additional serotypes and may also provide a temporary mechanism for evasion of serotype-specific host immune responses (14).

PFGE genotyping of the 89 isolates showed that the majority of penicillin-susceptible and -intermediate S. pneumoniae isolates were genetically unrelated. Penicillin-resistant isolates demonstrated less genetic variability, suggesting that clonal dissemination may contribute to the widespread distribution of penicillin-resistant S. pneumoniae in Canada. The overall heterogeneity of these isolates, however, is also suggestive of independent mutational events and is congruent with the theory that resistant isolates have arisen de novo through the acquisition of low-affinity penicillin-binding protein resistance determinants.

Interestingly, PFGE revealed no reduction in the diversity of genotypes among ciprofloxacin-nonsusceptible pneumococci. Ciprofloxacin-susceptible S. pneumoniae isolates, in fact, demonstrated less genetic variability than isolates with reduced susceptibility. In agreement with the previous observations of Alou et al. (1) and Chen et al. (4), these results suggest that the emergence of ciprofloxacin-resistant S. pneumoniae is currently not attributable to clonal dissemination. It appears, instead, that the increased prevalence of ciprofloxacin-nonsusceptible S. pneumoniae in Canada is primarily related to the acquisition of point mutations within the quinolone resistance determining regions of gyrA (DNA gyrase) and parC (topoisomerase IV), presumably under the selective pressure of increasing fluoroquinolone use, in multiple indigenous strains of S. pneumoniae. Given the changing epidemiology of antibiotic resistance worldwide, combined methods of phenotypic and genotypic surveillance will continue to play an important role in tracking the evolutionary changes that allow for early detection of potentially invasive multidrug-resistant pneumococcal clones.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alou, L., M. Ramirez, C. Garcia-Rey, J. Prieto, and H. de Lencastre. 2001. Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates with reduced susceptibility to ciprofloxacin in Spain: clonal diversity and appearance of ciprofloxacin-resistant epidemic clones. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2955-2957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Appelbaum, P. C. 1997. Antimicrobial resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae: an overview. Clin. Infect. Dis. 15:77-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caimano, M. J., G. G. Hardy, and J. Yother. 1998. Capsule genetics in Streptococcus pneumoniae and a possible role for transposition in the generation of the type 3 locus. Microb. Drug Resist. 4:11-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen, D. K., A. McGeer, J. C. de Azavedo, and D. E. Low. 1999. Decreased susceptibility of Streptococcus pneumoniae to fluoroquinolones in Canada. N. Engl. J. Med. 341:233-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feikin, D. R., and K. P. Klugman. 2002. Historical changes in pneumococcal serogroup distribution: implications for the era of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines. Clin. Infect. Dis. 35:547-555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hall, L. M. C., R. A. Whiley, B. Duke, R. C. George, and A. Efstratiou. 1996. Genetic relatedness within and between serotypes of Streptococcus pneumoniae from within the United Kingdom: analysis of multilocus enzyme electrophoresis, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, and antimicrobial resistance patterns. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:853-859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ip, M., D. J. Lyon, R. W. H. Yung, C. Chan, and A. F. B. Cheng. 1999. Evidence of clonal dissemination of multidrug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae in Hong Kong. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:2834-2839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Louie, M., L. Louie, G. Papia, J. Talbot, M. Lovgren, and A. E. Simor. 1999. Molecular analysis of the genetic variation among penicillin-susceptible and penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae serotypes in Canada. J. Infect. Dis. 179:892-900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lovgren, M., J. S. Spika, and J. A. Talbot. 1998. Invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae infections: serotype distribution and antimicrobial resistance in Canada, 1992-1995. CMAJ 158:327-331. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McGee, L., C. E. Goldsmith, and K. P. Klugman. 2002. Fluoroquinolone resistance among clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae belonging to international multiresistant clones. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 49:173-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Munoz, R., J. M. Musher, M. Crain, D. E. Briles, A. Marton, A. J. Parkinson, U. Sorenson, and A. Tomasz. 1992. Geographic distribution of penicillin-resistant clones of Streptococcus pneumoniae: characterization by penicillin-binding protein profile, surface protein A typing, and multilocus enzyme analysis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 15:112-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2000. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. Approved standard M7-A5, 5th ed. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 13.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2000. MIC testing: supplemental tables. M100-S10 (M7). National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 14.Tomasz, A. 1999. New faces of an old pathogen: emergence and spread of multidrug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae. Am. J. Med. 107:55S-62S. [DOI] [PubMed]