A constellation of reactive intermediates — electrophiles and free radicals — capable of damaging cellular constituents is generated during normal physiological or pathophysiological processes. The consequences of this damage include enhanced mutation rates, altered cell signaling, and events summarized in other articles in this Perspective series. In many cases, the initially generated reactive intermediates convert cellular constituents into second-generation reactive intermediates capable of inducing further damage. Cells have adapted to the existence of reactive intermediates by the evolution of defense mechanisms that either scavenge these intermediates or repair the damage they cause. High levels of damage can lead to cell death through apoptosis or necrosis. This article provides an overview of DNA and protein damage by endogenous electrophiles and oxidants and an introduction to the consequences of this damage.

First-generation reactive intermediates

Some reactive intermediates are produced as diffusible cofactors in normal metabolic pathways. For example, S-adenosylmethionine is a cofactor for many methylation reactions that are required in biosynthesis or in regulation of gene expression. The latter role requires its presence in the nucleus, where it also can react nonenzymatically with DNA bases to produce a variety of methylated derivatives. Some of these methylated DNA bases are highly mutagenic during DNA replication (see below).

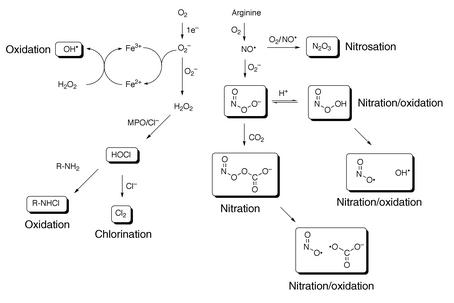

Most reactive intermediates are produced as unavoidable consequences of our existence in an aerobic environment (Figure 1). Utilization of O2 for energy production puts us at risk because of the generation of reactive oxidants as products of O2 reduction. Mitochondria reduce O2 to water via cytochrome oxidase as the final step in respiratory electron transport. Although most of the electrons are successfully transferred down the chain, estimates suggest that up to 10% of the reducing equivalents from NADH leak to form superoxide anion (O2–) and H2O2, which diffuse from the mitochondria (1). Macrophages and neutrophils reduce O2 to O2– via NADPH oxidase as part of the host defense system. Most of the O2– generated in inflammatory cells dismutates to form H2O2, which is a substrate for myeloperoxidase. O2– is also generated in epithelial cells by the action of an NAPDH oxidase complex that is related to the oxidase complex in phagocytic cells but that has a much lower capacity for O2– generation (2). The low flux of oxidants in epithelial cells is believed to play a role in signaling.

Figure 1.

Reactive intermediates generated from superoxide and nitric oxide. MPO, myeloperoxidase.

In addition to serving as a source of H2O2, O2– can react with ferric ion or nitric oxide to generate more potent oxidants (Figure 1). Reduction of ferric ion produces ferrous ion, which can reduce H2O2 to hydroxide ion and hydroxyl radical. Hydroxyl radical has a redox potential of 2.8 V, so it is an extremely strong oxidant capable of oxidizing virtually any molecule it encounters. Inflammatory cells generate copious amounts of NO and O2– by the action of inducible NO synthase and NADPH oxidase, respectively. Both species are important components of the host defense system. Chronic activation of the inflammatory response can induce collateral damage in adjacent normal tissue, which contributes to a range of diseases (see below and other articles in this Perspective series).

Reaction of O2– with NO produces peroxynitrite (ONOO–). ONOO– and its protonated form, peroxynitrous acid (ONOOH), react with cellular nucleophiles or oxidize hemeproteins to ferryl-oxo derivatives. Both ONOOH and ferryl-oxo complexes are strong oxidants. ONOOH is a direct oxidant and also undergoes homolysis to produce hydroxyl radical and NO2• (3, 4). Approximately 25% of these radicals escape the solvent cage to react with cellular constituents (5). ONOO– reacts with CO2 to form a carbonate adduct, nitrosoperoxycarbonate (ONO2CO2–) (6). The level of CO2 in most tissues is sufficient to trap all of the ONOO– released from inflammatory cells. The carbonate adduct is not as strong an oxidant as ONOO– or ONOOH, but it is an effective nitrating agent. The mechanism of nitration is believed to involve homolytic scission of ONO2CO2– to carbonate radical, which can either oxidize NO2• to NO2+ or oxidize DNA or protein to a derivative that then couples with NO2• to form a nitro derivative (e.g., tyrosine→tyrosyl radical; guanine→guanyl radical) (7).

In the presence of O2, NO generates a nitrosating agent that reacts with sulfhydryl groups to form S-nitroso derivatives (8). The chemistry of nitrosation is complex, but N2O3 appears to be the principal nitrosating agent produced. S-nitroso derivatives of proteins can demonstrate altered structural and functional properties depending upon their location in the protein. They also can transfer the nitroso group to other thiol-containing molecules (e.g., glutathione) or react with thiols to form mixed disulfides and release nitroxyl anion (NO–).

H2O2 produced by inflammatory cells oxidizes myeloperoxidase to a higher oxidation state that has a redox potential in excess of 1 V. This higher oxidation state (a ferryl-oxo complex) oxidizes Cl– to HOCl, which is capable of oxidizing or chlorinating cellular macromolecules (Figure 1) (9). HOCl also reacts with amines to form chloramines or with Cl– to form Cl2 gas; the latter chlorinates DNA or protein (10). A similar cascade of reactions is triggered by bromoperoxidase in eosinophils (11). Myeloperoxidase also can oxidize nitrite to NO2•, which can react with NO to form N2O3. This reaction may serve as an alternate pathway of protein nitrosation to the uncatalyzed reaction that produces N2O3 (which requires four NOs and O2) (12).

Second-generation reactive intermediates

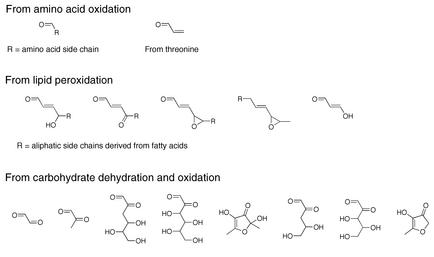

The oxidants generated from O2 reduction react with cellular components to produce a range of unstable oxidation products that can break down to diffusible electrophiles (Figure 2). For example, myeloperoxidase oxidizes α-amino acids to aldehydes; of particular interest is the oxidation of threonine to acrolein (13). Polyunsaturated fatty acid residues in phospholipids are very sensitive to oxidation at the central carbon of their pentadienyl backbone. Oxidation of the pentadienyl functionality by oxidants such as hydroxyl radical and ONOOH leads to a complex series of reactions that generate a range of electrophilic derivatives (Figure 2) (14). These include aldehydes and epoxides that are capable of reacting with protein or nucleic acid. α,β-Unsaturated aldehydes are particularly important oxidation products, because they have two sites of reactivity, which leads to the formation of cyclic adducts or cross-links. Epoxyaldehydes display complex reactivity toward nucleophiles, including the transfer of a two-carbon unit to DNA bases (15). A series of dehydration and oxidation reactions leads to the formation of aldehydes and ketones from carbohydrates (Figure 2) (16). These compounds are capable of reacting with protein nucleophiles to form advanced glycation end products. So, when considering the consequences of the generation of cellular electrophiles and free radicals, one must realize that primary oxidants (e.g., HO•, ONOOH) can give rise to a range of secondary oxidants, free radicals, and electrophiles. Obviously, cells devote considerable energy to protecting themselves from the deleterious effects of this panoply of reactive intermediates, but consideration of these mechanisms is beyond the scope of this Perspective.

Figure 2.

Reactive intermediates derived from amino acid, lipid, and carbohydrate oxidation.

Endogenous DNA damage

Exposure to endogenous oxidants and electrophiles leads to increases in damage to cellular macromolecules, including DNA. This section catalogs the major types of DNA damage and how they affect replication. DNA damage can result from reactions with nucleic acid bases, deoxyribose residues, or the phosphodiester backbone. The majority of the literature focuses on damage to bases or degradation of deoxyribose residues (17). Unrepaired DNA lesions accumulate with time and can contribute to the development of age-related diseases.

The consequences of DNA damage have been analyzed in vitro through polymerase bypass and enzymatic repair experiments and in vivo using site-specific mutagenesis experiments in bacterial and mammalian cells (18, 19). The extent of DNA damage has been evaluated by examination of tissues for adduct content (20). Adducts have been quantified at levels from as low as 1 in 109 to as high as 1 in 106 nucleotides, corresponding to approximately 3–3,000 adducts per cell. Though there is a great deal of interesting and controversial work defining adduct levels in various tissues, those data are beyond the scope of this Perspective. Due to space limitations, only a few illustrative examples of specific types of damage and their effects are discussed.

Hydroxyl radical–mediated DNA damage

Hydroxyl radical can add to double bonds of DNA bases or abstract hydrogen atoms from either methyl groups or deoxyribose residues (21) (Figure 3). Hydroxyl radical reacts with purines by adding to the 7,8 double bond to generate the 8-oxo-7,8-dihydrodeoxyguanosine (8-oxo-dG) that is more abundant than 8-oxo-7,8-dihydrodeoxyadenosine (8-oxo-dA) (22). Hydroxyl radical also adds to the 5,6 double bond of pyrimidines to produce pyrimidine glycols (23). Alternatively, hydrogen abstraction from the 5-methyl group of thymine can produce a carbon-centered radical that reacts with molecular oxygen to form a hydroperoxide; this hydroperoxide is reduced to hydroxymethyl-dU. Hydrogen-atom abstraction from deoxyribose can lead to single-strand breaks concomitant with the formation of base propenals (21). The latter are substituted enals and can react with nucleophilic sites elsewhere on DNA (see below).

Figure 3.

Endogenous products of DNA damage.

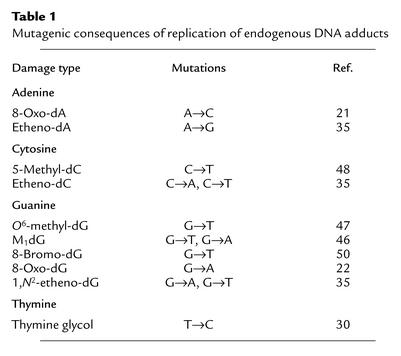

8-Oxo-dG induces transversions to T or C in both in vitro replication experiments and in vivo mutagenesis experiments (Table 1) (24, 25). A→C mutations have been observed as a result of in vitro replication of 8-oxo-dA (26). 8-Oxo-dG and 8-oxo-dA are known to undergo imidazole ring-opening to formamidopyrimidine (FAPy) adducts, which are minor, alkali-labile products of purine oxidation (27). Both 8-oxo-dG and FAPy adducts are repaired by glycosylases in prokaryotic and eukaryotic systems (28).

Table 1.

Mutagenic consequences of replication of endogenous DNA adducts

Hydroxyl radical damage to pyrimidines is also mutagenic. 5-Hydroxydeoxycytidine (5-hydroxy-dC) induces C→T and C→A mutations in vitro and C→T transitions in vivo (29). 5-Hydroxy-dC also deaminates to 5-hydroxy-deoxy-uracil, which codes as T. This provides an additional mechanism for the induction of C→T transitions. Thymidine glycol causes T→C mutations in vivo (30, 31).

Nitric oxide–mediated DNA damage

As discussed earlier, nitric oxide can form ONOOH, ONO2CO2–, and N2O3. These reactive intermediates can damage DNA directly. ONOOH and ONO2CO2– have been shown to form nitrated nucleosides, the most abundant of which occur on dG (e.g., 8-nitro-dG) (32). 8-Nitro-dG is an unstable adduct, and its glycosidic bond readily hydrolyzes to form an abasic site. Strand cleavage, seen when cells are exposed cells to ONOOH, is presumed to arise from 8-nitro-dG depurination (32). Alternatively, 8-nitro-dG may decompose by reaction with another equivalent of ONOOH to form 8-oxo-dG (33). 8-Oxo-dG itself can be oxidized by ONOOH to form degradation products; 3a-hydroxy-5-imino-3,3a,4,5-tetrahydro-1H-imidazo[4,5-d]imidazol-2-one is an intermediate formed from 8-oxo-dG at low ONOOH concentrations (32).

N2O3 reacts with the exocyclic amines of 2′-deoxyadenosine (dA), 2′-deoxycytidine (dC), and 2′-deoxyguanosine (dG) to produce nitroso and then diazo intermediates that are hydrolyzed to hypoxanthine, uracil, and xanthine; these are all potentially mispairing lesions. Human cells treated with NO exhibit both G→A transitions and G→T transversions, presumably from uracil and xanthine, respectively (32, 34). Furthermore, adjacent guanines can cross-link by an N2O3-mediated conversion of the amine on one guanine to a diazonium ion, followed by the attack of the exocyclic amine of the neighboring dG (32). N2O3 also has been shown to induce single-strand breaks on naked DNA and in intact cells.

Enal and exocyclic adducts

Enals can react at the exocyclic amino groups of dG, dA, and dC to form various alkylated products. Some common enals that cause DNA damage are malondialdehyde (MDA), acrolein, crotonaldehyde, and 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE). Enals are bifunctional electrophiles that present two reactive sites to DNA. The most common adducts arising from enals are exocyclic adducts such as etheno adducts from dA, dG, and dC; a pyrimidopurinone (M1dG) adduct from dG; and 8-hydroxypropanodeoxyguanosine (HO-PdG) adducts from dG. Etheno adducts also arise from reaction of exogenous sources such as vinyl chloride, and substituted etheno adducts originate from the 4-HNE derivative 4-oxo-nonenal (35, 36).

Etheno adducts are mispairing and mutagenic in bacterial and mammalian cells, although significant differences in mutagenicity have been described in prokaryotes and eukaryotes with regard to etheno-dA (35). Bacterial and mammalian cells have evolved base excision repair pathways to deal with etheno adducts. 1,N6-etheno-dA and, to a lesser extent, N2,3-etheno-dG are excised by N-methylpurine-glycosylases, whereas 3,N4-etheno-dC has been shown to be repaired by a mismatch-specific thymine-DNA glycosylase (37–39).

The M1dG adduct arises by reaction of MDA with dG residues (40). When positioned in duplex DNA opposite dC, M1dG undergoes hydrolytic ring-opening to N2-oxopropenyl-dG (41). Both the ring-closed and the ring-opened adducts are mutagenic in bacteria (G→A and G→T in both cell types) (42). The mutagenic frequency induced by the ring-opened form is lower than that observed for the ring-closed form.

Crotonaldehyde is mutagenic and forms diastereomeric six-membered ring adducts (6-methyl–HO-PdG) in vitro (43). HO-PdG, the structurally related adduct derived from acrolein, is mutagenic in vitro and in vivo (44, 45). The unsubstituted propano-dG (PdG) adduct is mutagenic in vitro and in vivo and causes frameshift mutations (though PdG is not physiologically relevant) (42, 46). Some exocyclic adducts (e.g., M1dG and HO-PdG) are themselves electrophilic and may react with nucleophilic sites in small molecules, DNA, or protein, thereby forming cross-links (6).

DNA methylation

DNA methylation occurs through the nonenzymatic reaction of bases with S-adenosylmethionine and various exogenous methylating agents. The most common sites of damage are on 2′-deoxythymidine (dT), forming O4-methyl-dT; on dG, forming O6-methyl-dG and N7-methyl-dG; and on dA, forming N3-methyl-dA, N6-methyl-dA, and N7-methyl-dA (47). Enzymatic methylation with S-adenosylmethionine on cytosine plays a role in mammalian gene regulation and imprinting, which can lead to functional inactivation of genes.

Methylated bases are mispaired in vitro and in vivo and can interfere with the binding of DNA enzymes and regulatory elements. Mutagenic events in Escherichia coli and mammalian cells reveal that O6-methyl-dG mispairs with thymidine to generate G→A transitions (47). O4-methyl-dT causes T→C transitions, whereas N3-methyl-dA and N6-methyl-dA promote A→G transitions and abasic site formation (47). Methylation on N7 of purines causes destabilization of the glycosidic bond, and subsequent depurination to an abasic site. A number of glycosylases from prokaryotes and eukaryotes have been isolated that remove alkyl adenine damage. O6-methyl-dG and alkyl-substituted adenine also have been directly implicated in methylation sensitivity in a variety of cell types (47). Strains with compromised or deleted O6-methyl-dG repair (such as methylguanine methyltransferase) or alkyl adenine repair (encoded by AlkA in E. coli or by aag in humans) demonstrate higher levels of mutation and cell death when exposed to methylating agents (48).

Halogens

The generation of HOCl provides a pathway for the halogenation of DNA bases. 5-Chloro-dC has been observed as the major product of reaction of HOCl with DNA and has been detected in human tissues (49). Similarly, eosinophil peroxidases produce hypobromous acid (HOBr), which generates 5-bromo-dC and the deamination product 5-bromo-dU (11). Halogenation at the 5 position of pyrimidines may lead to mispairing. Chlorinated products, most notably 8-chloro-purines, have been isolated (50). These lesions are mispairing and cause transitions and transversions (50).

In addition to causing replication errors that lead to genetic disease, DNA damage triggers signaling cascades that slow cell cycle progression or lead to apoptosis. For example, treatment of cultured colon cancer cells with concentrations of MDA that lead to levels of M1dG of approximately 1 in 107 nucleotides induces cell cycle arrest at the G1/S and G2/M transitions (51). The sensors of DNA damage and the signaling pathways that lead to cell cycle arrest and apoptosis are areas of very active investigation.

Amino acid and protein damage

Protein damage that accumulates during oxidative stress is unquestionably more diverse than the spectrum of intermediates that causes it. Modification of polypeptides by reactive species can occur on the peptide backbone, various nucleophilic side chains, and redox-sensitive side chains (Figure 4). For many of the reactive species discussed earlier, the modifications that they carry out on proteins have been characterized, and several of their molecular targets are known. In many cases, the chemistry associated with protein damage is dynamic and reversible, although several types of protein adducts accumulate during aging and/or age-related diseases.

Figure 4.

Endogenous damage to amino acid side chains.

Damage to peptide backbones

Free radicals produced during oxidative stress can damage the peptide backbone, resulting in the generation of protein carbonyls. The process is initiated by hydrogen abstraction from the α-carbon in a peptide chain. If two protein radicals are in close proximity, they may cross-link with one another by radical coupling (52). Alternatively, O2 can attack the α-carbon–centered radical to form peroxide intermediates, leading to rearrangement and subsequent cleavage of the peptide bond to form carbonyl-containing peptides (52). Protein carbonyls also may be generated by the oxidation of several amino acid side chains (e.g., Lys, Arg, Pro) and by the formation of Michael adducts between nucleophilic residues and α,β-unsaturated aldehydes (see below) (53). Carbonyl content can be analyzed by reaction of 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine with proteins to form the corresponding hydrazone. As a marker of oxidative damage to proteins, protein carbonyls have been shown to accumulate during aging and age-related disease in a variety of organisms (53). Levels of protein carbonyls are, therefore, a potentially useful indicator of intracellular redox status.

Modification of side chains by intracellular oxidants and radicals

Intracellular oxidants and radicals carry out numerous modifications on the side chains of amino acid residues in polypeptides. Although most amino acids can be modified by various endogenous oxidants, residues commonly modified by HO•, O2–, HOCl, ONOOH, and ONO2CO2– include cysteine, tyrosine, and methionine. Reversible oxidation of the sulfhydryl group on cysteine converts it to cysteine sulfenic acid, which can react with thiols or undergo further irreversible oxidation to a sulfinic acid and a sulfonic acid (Figure 4) (54). Thiols with particularly low pKa’s are most susceptible to oxidation. Sulfenic acids in proteins can react with glutathione or other sulfhydryl-containing molecules to form disulfide bonds (54). In the case of glutathione, the formation of the disulfide bond is termed glutathionylation. Disulfide bonds accumulate under oxidizing conditions, but they can be readily reduced to free sulfhydryl groups by the enzyme thioredoxin or by reducing agents (55).

Recent discoveries in the biology of nitrosating agents, such as S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO), have revealed that several proteins are particularly susceptible to S-nitrosation at specific cysteine residues. In searching for consensus nitrosation sites, it has been suggested that there are both hydrophobic and acid-base motifs in target proteins adjacent to the site of their modification (56). GSNO, a commonly used exogenous nitrosating agent, has been detected in vivo at micromolar concentrations in brain tissue and can directly transfer NO equivalents to target protein thiols (8). Additionally, other mechanisms of S-nitrosation of nucleophilic cysteines (e.g., by N2O3) are plausible (8). S-nitrosothiols in proteins can react with free sulfhydryl groups to create disulfide bonds and can be reduced by various reductants (8). Although the chemical pathways through which nitric oxide forms S-nitrosocysteine are complex, experiments using induced expression of NO synthase isoforms and neuronal NO synthase knockout cells have established that NO production increases levels of overall protein S-nitrosation (57, 58). S-nitrosation of proteins is potentially a key method that cells use to mediate inflammatory responses and other NO-regulated processes.

Methionine residues in proteins are highly susceptible to oxidation by various reactive intermediates. Upon oxidation, methionine is converted to methionine sulfoxide and can be further oxidized to methionine sulfone (59). Oxidation of methionine residues in proteins can be reversed by methionine sulfoxide reductase A (MSRA), an NADH-dependent enzyme that reduces methionine-R-sulfoxide to methionine (59), or by selenoprotein R, an enzyme that acts on the methionine-S-sulfoxide stereoisomer (60). It has been proposed that methionine residues in proteins serve protective roles by preventing oxidative damage at other residues, since methionine oxidation is enzymatically reversible (59). In accordance with this hypothesis, mice lacking the MsrA gene have decreased life spans, behavioral abnormalities, and increased protein carbonyl levels (61). A separate study using a transgenic MSRA Drosophila model supports these observations by demonstrating that transgenic flies that overexpress MSRA live longer, more active lives when compared with wild-type littermates (62).

Oxidants generated during stress can modify the aromatic residues phenylalanine and tyrosine. Phenylalanine is sensitive to oxidation by HO• and transition metals, which cause its conversion to o- and m-tyrosine. Tyrosine residues can be modified by several oxidants, including HOCl, ONOOH, and ONO2CO2– (63). A variety of oxidative modifications can occur to tyrosine side chains in proteins, including formation of o,o′-dityrosine, 3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine, 3-nitrotyrosine, and 3-chlorotyrosine. These modifications are likely irreversible, so inactivation of various proteins in this manner could have lasting detrimental effects. Recent reports have documented that 3-nitrotyrosine and 3-chlorotyrosine can be generated ex vivo during sample processing, illustrating the limitations of some quantitative methods that do not use isotopically labeled internal standards that can distinguish in vivo from ex vivo generation (e.g., immunochemical, spectroscopic, and electrochemical detection). This underscores the importance of developing robust analytical methods and validating them in in vivo settings. Indeed, some advances in the mass spectrometric quantification of tyrosine modification have been described (64–66). Application of these methods has demonstrated increases in oxidative damage to aromatic amino acid residues in atherosclerosis and other degenerative diseases, supporting the hypothesis that aromatic amino acid damage contributes to the development and/or progression of various age-related diseases (67, 68).

Modification of proteins by aldehydic intermediates

Modification of amino acids by α,β-unsaturated aldehydes commonly occurs on the nucleophilic residues cysteine, histidine, and lysine (Figure 4) (16, 69). The chemistry that shorter α,β-unsaturated aldehydes undergo when reacting with proteins is slightly different from that of the reactions depicted in Figure 4. For instance, two molecules of acrolein react with the ε-amino group of lysine to form predominantly a cyclic 3-formyl-3,4-dehydropiperidino adduct (16). MDA mainly reacts with lysine residues by Michael addition, but other forms of multimerized MDA have been found to react with lysine as well (16). Michael adducts between 4-hydroxy-2-alkenals and cysteine, histidine, and lysine are formed as depicted, as well as Schiff base adducts that form only following reaction with the amino group on lysine residues (16, 69). The products of 4-hydroxy-2-alkenals can be converted to more stable structures, including cyclic hemiacetals, pyrroles, and various other structures (16, 69). Increased levels of acrolein and 4-HNE protein adducts, abundant products of lipid peroxidation, are found in cardiovascular disease and neurodegenerative diseases (16, 69).

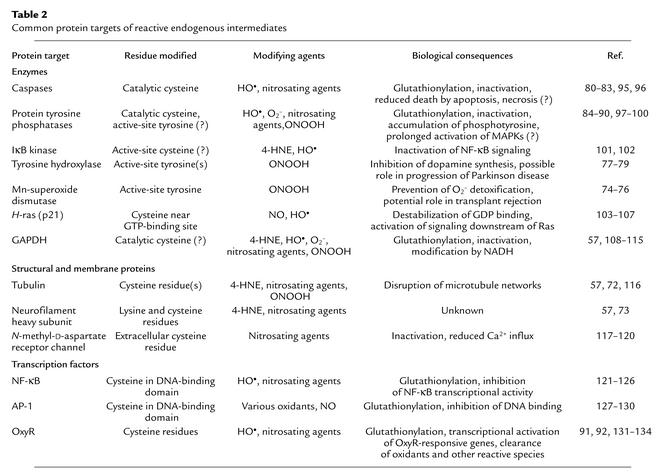

Protein targets of reactive species

Endogenous oxidants and electrophiles modify a host of proteins that run the gamut of biological functions (Table 2). For most protein targets, there is a remarkable specificity in the type and location of the residue(s) modified. An exhaustive description of these targets, the effect that is mediated, and the modifying agent that carries out the damage is not possible due to space limitations. For more information, the reader is referred to other articles that deal with protein targets of individual modifying agents (59, 70, 71). A survey of common protein targets is listed in Table 2 and is expounded below. Where possible, the modifications are described, and the biological consequences are discussed.

Table 2.

Common protein targets of reactive endogenous intermediates

Damage to structural proteins

Cell structure is maintained through a variety of cytoskeletal components including tubulin and filamentous proteins. Due to their abundance in specific cell types, these proteins are common targets of a variety of reactive species. Although the consequences of these modifications are still unclear, functional assays have been developed for some damaging agents. Tubulin isoforms are modified in vitro and in vivo by a number of intermediates, including nitrosating agents and 4-HNE (57, 72). 4-HNE forms Michael adducts with tubulin isoforms and disrupts microtubule assembly in neuroblastoma cells, blocking neurite outgrowth (72). Additionally, neurofilament heavy chains have been identified as targets of nitrosating agents and 4-HNE (57, 73). The mechanistic features and the effect(s) seen with modification of neurofilaments by these and other agents remain to be elucidated.

Damage to metabolic and detoxification enzymes

Disruption of housekeeping enzymatic activities can occur in response to various endogenously produced electrophiles and radicals and may serve to potentiate stress responses. For instance, Mn-superoxide dismutase has been shown to be inactivated in rejected kidney transplants (74). Accumulation of 3-nitrotyrosine, an adduct of ONO2CO2–, is observed on Mn-superoxide dismutase in the same patients (74), presumably on a single active-site tyrosine (75, 76). Upon inactivation of this key detoxifying enzyme, superoxide and ONOO– can accumulate and potentially trigger more protein and DNA damage.

Tyrosine hydroxylase is the rate-limiting enzyme in the biosynthesis of L-dopamine, an essential chemical for the proper function of dopaminergic neurons. L-dopamine levels are substantially reduced in Parkinson disease patients. It has recently been shown that tyrosine hydroxylase isolated from the brains of mice that are models for Parkinson disease contains 3-nitrotyrosine adducts and exhibits reduced enzymatic activity (77). Upon in vitro modification of tyrosine hydroxylase with ONOOH, several active-site tyrosine residues are damaged (78, 79). These data support the hypothesis that tyrosine hydroxylase is a critical target for oxidative inactivation in Parkinson disease.

Damage to proteins involved in cell signaling and gene expression

Numerous studies have revealed the importance of reactive species in altering cell signaling pathways that are critical for cell growth, differentiation, and/or survival. Targets of reactive intermediates include apoptotic caspases, protein tyrosine phosphatases, certain kinases, and the transcription factors AP-1, NF-κB, and OxyR. Of these, perhaps the most extensive work has been performed on modification of protein tyrosine phosphatases, caspases, and OxyR.

Caspases, the cysteine protease executioners of the apoptotic response, can be modified by oxygen radicals and various nitrosating agents. These enzymes catalyze the proteolysis of proteins necessary for cell survival, using a nucleophilic cysteine residue in the active site to stimulate cleavage of target proteins at consensus aspartate residues. Several studies have shown that caspase-3, upon modification by radicals and nitrosating agents, is inactivated (80–82); presumably the inactivating modification of caspase-3 occurs on its catalytic cysteine residues (80–82). It has recently been demonstrated that S-nitrosated caspase-3 molecules are predominantly localized to the mitochondria (83), suggesting that this regulatory modification may prevent activation of caspase-3 in specific cellular organelles. The modification of caspase-3 by various agents represents a potential method for regulating its activity, thereby preventing apoptosis.

A large family of protein tyrosine phosphatases exists to modulate signaling by growth factors and other agonists. All members of the protein tyrosine phosphatase family function via a common catalytic mechanism that utilizes a single cysteine residue; these active-site cysteines have pKa’s of approximately 5.5. Because of their low pKa’s, the catalytic cysteines are susceptible to inactivation by oxygen radicals, ONOOH, and nitrosating agents, being converted to a sulfenic acid, a sulfonic acid, S-nitrosocysteine, or a glutathionylated cystine (84–90). In cells subjected to oxidative stress, inactivation of protein tyrosine phosphatases is associated with an accumulation of phosphotyrosine and the potential for prolonged activation of specific stress-responsive and/or mitogenic signaling pathways (87).

One prototypical transcription factor that is regulated by oxidation and S-nitrosation is the bacterial protein OxyR. This homotetrameric protein undergoes a conformational change and becomes activated when critical cysteine residues are nitrosated or oxidized (91). Subsequently, OxyR activates transcription of several bacterial genes that protect against and/or repair oxidative damage. Various modifications of OxyR (i.e., S-nitrosation, sulfenic acid formation, and glutathionylation) influence its DNA-binding and transcriptional activation properties differently, suggesting that these modifications are responsible for varied biological responses (92). Knowledge gained from the study of OxyR may be useful in studying the effects of oxidants on oxidant-sensitive eukaryotic transcription factors, such as AP-1 and NF-κB.

Proteomic approaches for identifying protein targets of reactive species

Proteome-wide screening for modified proteins promises to be an exciting area of research in the immediate future. High-throughput methods have recently been developed for examining global protein S-nitrosation, glutathionylation, and tyrosine nitration (57, 93, 94). Although most current methods use the power of mass spectrometry for identification of proteins, the approaches taken to enrich for and isolate modified proteins differ. For example, an elegant approach to the isolation of S-nitrosated proteins was recently reported (57). Free thiol groups were reacted with methyl methanethiosulfonate, and then S-NO groups were reduced to free thiols by treatment with ascorbate. Subsequently, using streptavidin agarose beads, the newly released protein thiols were converted to biotin conjugates to enrich for proteins. Peptides from isolated proteins were identified using matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization mass spectrometry. Approximately 15–20 proteins were identified as targets of nitrosating agents. The methodology was validated by confirmation that many targets of exogenous nitrosating agents are in vivo targets, as revealed by the lack of labeling in brain lysates from mice deficient in neuronal NO synthase.

In another method, glutathionylated proteins were identified by incubation of cells with radiolabeled cysteine in the absence of protein synthesis, exposure of T lymphocytes to agents that create an oxidative intracellular environment, isolation and detection of radiolabeled (i.e., glutathionylated) proteins, and identification of radiolabeled peptides by mass spectrometry (93). This study reveals that numerous proteins are targets for redox-dependent modification. Several of the enzymes identified were inactivated in in vitro assays, implying that glutathionylation of proteins upon alteration of cellular redox status is a potential mechanism for regulating the activity of many targets.

A similar methodology has been developed for identifying tyrosine damage by ONO2CO2– following exposure of cells or animals to inflammatory stimuli (94). This approach uses detection of proteins containing 3-nitrotyrosine residues by Western blotting following two-dimensional electrophoresis. Proteins from A549 cells, rat liver, or rat lung were partially transferred to membranes, and nitrated proteins were identified by Western blotting. The spots of the gel comigrating with those staining positive by Western blot were extracted and identified by mass spectrometry. Approximately 40 proteins were identified in this study as targets of ONO2CO2–, although the biological consequences of nitration in most cases remain to be determined.

Concluding thoughts

Research in the past twenty years has heightened our awareness of the importance of endogenous metabolic processes in cellular dysfunction, mutagenesis, and death. Much of this work has been descriptive, because the tools needed to ask discrete molecular questions were not available. However, there has been a dramatic and recent transformation in our ability to conduct qualitative and quantitative analysis of nucleic acid and protein modification. Thus, it is reasonable to assume that the next few years will witness a more precise definition of the events that lead from chemical modification to altered cellular function and/or heritable genetic change. This application of the tools of chemistry to biology will provide a strong experimental basis for the development of new diagnostic, therapeutic, and preventive strategies.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Celeste Riley for helpful editorial suggestions. Work in the Marnett laboratory is supported by research grants from the NIH (CA-77839, CA-87819, CA-89450, and GM-15431) and from the National Foundation for Cancer Research.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Nonstandard abbreviations used: superoxide anion (O2–); peroxynitrite (ONOO–); peroxynitrous acid (ONOOH); nitrosoperoxycarbonate (ONO2CO2–); nitroxyl anion (NO–); 8-oxo-7,8-dihydrodeoxyguanosine (8-oxo-dG); 8-oxo-7,8-dihydrodeoxyadenosine (8-oxo-dA); 5-hydroxydeoxycytidine (5-hydroxy-dC); 2′-deoxyadenosine (dA); 2′-deoxycytidine (dC); 2′-deoxyguanosine (dG); 2′-deoxythymidine (dT); malondialdehyde (MDA); 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE); pyrimidopurinone (M1dG); 8-hydroxypropanodeoxyguanosine (HO-PdG); methionine sulfoxide reductase A (MSRA).

References

- 1.Floyd RA, West M, Hensley K. Oxidative biochemical markers; clues to understanding aging in long-lived species. Exp. Gerontol. 2001;36:619–640. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(00)00231-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Babior BM. The NADPH oxidase of endothelial cells. IUBMB Life. 2000;50:267–269. doi: 10.1080/713803730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koppenol WH, Moreno JJ, Pryor WA, Ischiropoulos H, Beckman JS. Peroxynitrite: a cloaked oxidant from superoxide and nitric oxide. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1992;5:834–842. doi: 10.1021/tx00030a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hodges GR, Ingold KU. Cage escape of geminate radical pairs can produce peroxynitrate from peroxynitrite under a wide variety of experimental conditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:10695–10701. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldstein S, Czapski G, Lind J, Merenyi G. Gibbs energy of formation of peroxynitrite: order restored. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2001;14:657–660. doi: 10.1021/tx010066n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lymar SV, Hurst JK. Rapid reaction between peroxonitrite ion and carbon dioxide: implications for biological activity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:8867–8868. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Squadrito GL, Pryor WA. Mapping the reaction of peroxynitrite with CO2: energetics, reactive species, and biological implications. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2002;15:885–895. doi: 10.1021/tx020004c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hogg N. The biochemistry and physiology of S-nitrosothiols. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2002;42:585–600. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.42.092501.104328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Winterbourn CC, Vissers MC, Kettle AJ. Myeloperoxidase. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2000;7:53–58. doi: 10.1097/00062752-200001000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hazen SL, Hsu FF, Duffin K, Heinecke JW. Molecular chlorine generated by the myeloperoxidase hydrogen peroxide chloride system of phagocytes converts low density lipoprotein cholesterol into a family of chlorinated sterols. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:23080–23088. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.38.23080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henderson JP, et al. Bromination of deoxycytidine by eosinophil peroxidase: a mechanism for mutagenesis by oxidative damage of nucleotide precursors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001;98:1631–1636. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041146998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Dalen CJ, Winterbourn CC, Senthilmohan R, Kettle AJ. Nitrite as a substrate and inhibitor of myeloperoxidase. Implications for nitration and hypochlorous acid production at sites of inflammation. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:11638–11644. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.16.11638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hazen SL, Hsu FF, d’Avignon A, Heinecke JW. Human neutrophils employ myeloperoxidase to convert α-amino acids to a battery of reactive aldehydes: a pathway for aldehyde generation at sites of inflammation. Biochemistry. 1998;37:6864–6873. doi: 10.1021/bi972449j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Esterbauer H, Schaur RJ, Zollner H. Chemistry and biochemistry of 4-hydroxynonenal, malonaldehyde and related aldehydes. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1991;11:81–128. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(91)90192-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee SH, Oe T, Blair IA. 4,5-Epoxy-2(E)-decenal-induced formation of 1,N(6)-etheno-2′- deoxyadenosine and 1,N(2)-etheno-2′-deoxyguanosine adducts. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2002;15:300–304. doi: 10.1021/tx010147j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uchida K. Role of reactive aldehyde in cardiovascular diseases. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2000;28:1685–1696. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00226-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marnett LJ, Plastaras JP. Endogenous DNA damage and mutation. Trends Genet. 2001;17:214–221. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(01)02239-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singer B, Essigmann JM. Site-specific mutagenesis: retrospective and prospective. Carcinogenesis. 1991;12:949–955. doi: 10.1093/carcin/12.6.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang D, Kreutzer DA, Essigmann JM. Mutagenicity and repair of oxidative DNA damage: insights from studies using defined lesions. Mutat. Res. 1998;400:99–115. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(98)00066-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Swenberg JA, et al. DNA adducts: effects of low exposure to ethylene oxide, vinyl chloride and butadiene. Mutat. Res. 2000;464:77–86. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5718(99)00168-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chatgilialoglu C, O’Neill P. Free radicals associated with DNA damage. Exp. Gerontol. 2001;36:1459–1471. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(01)00132-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cadet J, et al. Hydroxyl radicals and DNA base damage. Mutat. Res. 1999;424:9–21. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(99)00004-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wagner JR, Hu C-C, Ames BN. Endogenous oxidative damage of deoxycytidine in DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1992;89:3380–3384. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.8.3380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tan X, Grollman AP, Shibutani S. Comparison of the mutagenic properties of 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2′-deoxyadenosine and 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2′-deoxyguanosine DNA lesions in mammalian cells. Carcinogenesis. 1999;20:2287–2292. doi: 10.1093/carcin/20.12.2287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gentil A, Le Page F, Cadet J, Sarasin A. Mutation spectra induced by replication of two vicinal oxidative DNA lesions in mammalian cells. Mutat. Res. 2000;452:51–56. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(00)00034-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shibutani S, Bodepudi V, Johnson F, Grollman AP. Translesional synthesis on DNA templates containing 8-oxo-7,8-dihydrodeoxyadenosine. Biochemistry. 1993;32:4615–4621. doi: 10.1021/bi00068a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Douki T, Martini R, Ravanat JL, Turesky RJ, Cadet J. Measurement of 2,6-diamino-4-hydroxy-5-formamidopyrimidine and 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine in isolated DNA exposed to gamma radiation in aqueous solution. Carcinogenesis. 1997;18:2385–2391. doi: 10.1093/carcin/18.12.2385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hazra TK, Hill JW, Izumi T, Mitra S. Multiple DNA glycosylases for repair of 8-oxoguanine and their potential in vivo functions. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 2001;68:193–205. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(01)68100-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feig DI, Sowers LC, Loeb LA. Reverse chemical mutagenesis: identification of the mutagenic lesions resulting from reactive oxygen species-mediated damage to DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1994;91:6609–6613. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.14.6609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McNulty JM, Jerkovic B, Bolton PH, Basu AK. Replication inhibition and miscoding properties of DNA templates containing a site-specific cis-thymine glycol or urea residue. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1998;11:666–673. doi: 10.1021/tx970225w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Basu AK, Loechler EL, Leadon SA, Essigmann JM. Genetic effects of thymine glycol: site-specific mutagenesis and molecular modeling studies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1989;86:7677–7681. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.20.7677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burney S, Caulfield JL, Niles JC, Wishnok JS, Tannenbaum SR. The chemistry of DNA damage from nitric oxide and peroxynitrite. Mutat. Res. 1999;424:37–49. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(99)00006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee JM, Niles JC, Wishnok JS, Tannenbaum SR. Peroxynitrite reacts with 8-nitropurines to yield 8-oxopurines. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2002;15:7–14. doi: 10.1021/tx010093d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jaiswal M, LaRusso NF, Gores GJ. Nitric oxide in gastrointestinal epithelial cell carcinogenesis: linking inflammation to oncogenesis. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2001;281:G626–G634. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.281.3.G626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barbin A. Etheno-adduct-forming chemicals: from mutagenicity testing to tumor mutation spectra. Mutat. Res. 2000;462:55–69. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(00)00014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blair IA. Lipid hydroperoxide-mediated DNA damage. Exp. Gerontol. 2001;36:1473–1481. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(01)00133-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Swenberg JA, et al. Formation and repair of DNA adducts in vinyl chloride- and vinyl fluoride-induced carcinogenesis. IARC Sci. Publ. 1999;150:29–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Singer B, Hang B. Mammalian enzymatic repair of etheno and para-benzoquinone exocyclic adducts derived from the carcinogens vinyl chloride and benzene. IARC Sci. Publ. 1999;150:233–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saparbaev M, Laval J. Enzymology of the repair of etheno adducts in mammalian cells and in Escherichia coli. IARC Sci. Publ. 1999;150:249–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marnett LJ. Chemistry and biology of DNA damage by malondialdehyde. IARC Sci. Publ. 1999;150:17–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mao H, Schnetz-Boutaud NC, Weisenseel JP, Marnett LJ, Stone MP. Duplex DNA catalyzes the chemical rearrangement of a malondialdehyde deoxyguanosine adduct. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999;96:6615–6620. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.6615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fink SP, Marnett LJ. The relative contribution of adduct blockage and DNA repair on template utilization during replication of 1,N2-propanodeoxyguanosine and pyrimido. Mutat. Res. 2001;485:209–218. doi: 10.1016/s0921-8777(01)00064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hecht SS, McIntee EJ, Wang M. New DNA adducts of crotonaldehyde and acetaldehyde. Toxicology. 2001;166:31–36. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(01)00436-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.VanderVeen LA, et al. Evaluation of the mutagenic potential of the principal DNA adduct of acrolein. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:9066–9070. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008900200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang IY, et al. Responses to the major acrolein-derived deoxyguanosine adduct in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:9071–9076. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008918200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fink SP, Reddy GR, Marnett LJ. Mutagenicity in Escherichia coli of the major DNA adduct derived from the endogenous mutagen malondialdehyde. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1997;94:8652–8657. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bignami M, O’Driscoll M, Aquilina G, Karran P. Unmasking a killer: DNA O(6)-methylguanine and the cytotoxicity of methylating agents. Mutat. Res. 2000;462:71–82. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(00)00016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jubb AM, Bell SM, Quirke P. Methylation and colorectal cancer. J. Pathol. 2001;195:111–134. doi: 10.1002/path.923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen HJ, Row SW, Hong CL. Detection and quantification of 5-chlorocytosine in DNA by stable isotope dilution and gas chromatography/negative ion chemical ionization/mass spectrometry. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2002;15:262–268. doi: 10.1021/tx015578g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Masuda M, et al. Chlorination of guanosine and other nucleosides by hypochlorous acid and myeloperoxidase of activated human neutrophils. Catalysis by nicotine and trimethylamine. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:40486–40496. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102700200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ji C, Rouzer CA, Marnett LJ, Pietenpol JA. Induction of cell cycle arrest by the endogenous product of lipid peroxidation, malondialdehyde. Carcinogenesis. 1998;19:1275–1283. doi: 10.1093/carcin/19.7.1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dean RT, Fu S, Stocker R, Davies MJ. Biochemistry and pathology of radical-mediated protein oxidation. Biochem. J. 1997;324:1–18. doi: 10.1042/bj3240001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Levine RL, Stadtman ER. Oxidative modification of proteins during aging. Exp. Gerontol. 2001;36:1495–1502. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(01)00135-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Claiborne A, et al. Protein-sulfenic acids: diverse roles for an unlikely player in enzyme catalysis and redox regulation. Biochemistry. 1999;38:15407–15416. doi: 10.1021/bi992025k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Arner ES, Holmgren A. Physiological functions of thioredoxin and thioredoxin reductase. Eur. J. Biochem. 2000;267:6102–6109. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hess DT, Matsumoto A, Nudelman R, Stamler JS. S-nitrosylation: spectrum and specificity. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001;3:E46–E49. doi: 10.1038/35055152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jaffrey SR, Erdjument-Bromage H, Ferris CD, Tempst P, Snyder SH. Protein S-nitrosylation: a physiological signal for neuronal nitric oxide. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001;3:193–197. doi: 10.1038/35055104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gow AJ, et al. Basal and stimulated protein S-nitrosylation in multiple cell types and tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:9637–9640. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100746200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Levine RL, Moskovitz J, Stadtman ER. Oxidation of methionine in proteins: roles in antioxidant defense and cellular regulation. IUBMB Life. 2000;50:301–307. doi: 10.1080/713803735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kryukov GV, Kumar RA, Koc A, Sun Z, Gladyshev VN. Selenoprotein R is a zinc-containing stereo-specific methionine sulfoxide reductase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:4245–4250. doi: 10.1073/pnas.072603099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Moskovitz J, et al. Methionine sulfoxide reductase (MsrA) is a regulator of antioxidant defense and lifespan in mammals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001;98:12920–12925. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231472998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ruan H, et al. High-quality life extension by the enzyme peptide methionine sulfoxide reductase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:2748–2753. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032671199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Podrez EA, Abu-Soud HM, Hazen SL. Myeloperoxidase-generated oxidants and atherosclerosis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2000;28:1717–1725. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00229-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Frost MT, Halliwell B, Moore KP. Analysis of free and protein-bound nitrotyrosine in human plasma by a gas chromatography/mass spectrometry method that avoids nitration artifacts. Biochem. J. 2000;345:453–458. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gaut JP, Byun J, Tran HD, Heinecke JW. Artifact-free quantification of free 3-chlorotyrosine, 3-bromotyrosine, and 3-nitrotyrosine in human plasma by electron capture-negative chemical ionization gas chromatography mass spectrometry and liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Biochem. 2002;300:252–259. doi: 10.1006/abio.2001.5469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Delatour T, Richoz J, Vuichoud J, Stadler RH. Artifactual nitration controlled measurement of protein-bound 3-nitro-L-tyrosine in biological fluids and tissues by isotope dilution liquid chromatography electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2002;15:1209–1217. doi: 10.1021/tx0200414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Heinecke JW. Oxidants and antioxidants in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis: implications for the oxidized low density lipoprotein hypothesis. Atherosclerosis. 1998;141:1–15. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(98)00173-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pennathur S, Jackson-Lewis V, Przedborski S, Heinecke JW. Mass spectrometric quantification of 3-nitrotyrosine, ortho-tyrosine, and o,o′-dityrosine in brain tissue of 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3, 6-tetrahydropyridine-treated mice, a model of oxidative stress in Parkinson’s disease. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:34621–34628. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.49.34621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sayre LM, Smith MA, Perry G. Chemistry and biochemistry of oxidative stress in neurodegenerative disease. Curr. Med. Chem. 2001;8:721–738. doi: 10.2174/0929867013372922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Stamler JS, Lamas S, Fang FC. Nitrosylation: the prototypic redox-based signaling mechanism. Cell. 2001;106:675–683. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00495-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Patel RP, et al. Cell signaling by reactive nitrogen and oxygen species in atherosclerosis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2000;28:1780–1794. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00235-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Neely MD, Sidell KR, Graham DG, Montine TJ. The lipid peroxidation product 4-hydroxynonenal inhibits neurite outgrowth, disrupts neuronal microtubules, and modifies cellular tubulin. J. Neurochem. 1999;72:2323–2333. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0722323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wataya T, et al. High molecular weight neurofilament proteins are physiological substrates of adduction by the lipid peroxidation product hydroxynonenal. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:4644–4648. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110913200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.MacMillan-Crow LA, Crow JP, Kerby JD, Beckman JS, Thompson JA. Nitration and inactivation of manganese superoxide dismutase in chronic rejection of human renal allografts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1996;93:11853–11858. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.MacMillan-Crow LA, Crow JP, Thompson JA. Peroxynitrite-mediated inactivation of manganese superoxide dismutase involves nitration and oxidation of critical tyrosine residues. Biochemistry. 1998;37:1613–1622. doi: 10.1021/bi971894b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yamakura F, Taka H, Fujimura T, Murayama K. Inactivation of human manganese-superoxide dismutase by peroxynitrite is caused by exclusive nitration of tyrosine 34 to 3-nitrotyrosine. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:14085–14089. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.23.14085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ara J, et al. Inactivation of tyrosine hydroxylase by nitration following exposure to peroxynitrite and 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998;95:7659–7663. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Blanchard-Fillion B, et al. Nitration and inactivation of tyrosine hydroxylase by peroxynitrite. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:46017–46023. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105564200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kuhn DM, et al. Peroxynitrite-induced nitration of tyrosine hydroxylase: identification of tyrosines 423, 428, and 432 as sites of modification by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry and tyrosine-scanning mutagenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:14336–14342. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200290200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mannick JB, et al. Fas-induced caspase denitrosylation. Science. 1999;284:651–654. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5414.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rossig L, et al. Nitric oxide inhibits caspase-3 by S-nitrosation in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:6823–6826. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.11.6823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zech B, Wilm M, van Eldik R, Brune B. Mass spectrometric analysis of nitric oxide-modified caspase-3. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:20931–20936. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.30.20931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mannick JB, et al. S-nitrosylation of mitochondrial caspases. J. Cell Biol. 2001;154:1111–1116. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200104008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Caselli A, et al. The inactivation mechanism of low molecular weight phosphotyrosine-protein phosphatase by H2O2. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:32554–32560. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.49.32554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Barrett WC, et al. Roles of superoxide radical anion in signal transduction mediated by reversible regulation of protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:34543–34546. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.49.34543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Barrett WC, et al. Regulation of PTP1B via glutathionylation of the active site cysteine 215. Biochemistry. 1999;38:6699–6705. doi: 10.1021/bi990240v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Meng TC, Fukada T, Tonks NK. Reversible oxidation and inactivation of protein tyrosine phosphatases in vivo. Mol. Cell. 2002;9:387–399. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00445-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Takakura K, Beckman JS, MacMillan-Crow LA, Crow JP. Rapid and irreversible inactivation of protein tyrosine phosphatases PTP1B, CD45, and LAR by peroxynitrite. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1999;369:197–207. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chiarugi P, et al. Two vicinal cysteines confer a peculiar redox regulation to low molecular weight protein tyrosine phosphatase in response to platelet-derived growth factor receptor stimulation. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:33478–33487. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102302200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Denu JM, Tanner KG. Specific and reversible inactivation of protein tyrosine phosphatases by hydrogen peroxide: evidence for a sulfenic acid intermediate and implications for redox regulation. Biochemistry. 1998;37:5633–5642. doi: 10.1021/bi973035t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Choi H, et al. Structural basis of the redox switch in the OxyR transcription factor. Cell. 2001;105:103–113. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00300-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kim SO, et al. OxyR: a molecular code for redox-related signaling. Cell. 2002;109:383–396. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00723-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Fratelli M, et al. Identification by redox proteomics of glutathionylated proteins in oxidatively stressed human T lymphocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:3505–3510. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052592699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Aulak KS, et al. Proteomic method identifies proteins nitrated in vivo during inflammatory challenge. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001;98:12056–12061. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221269198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mohr S, Zech B, Lapetina EG, Brune B. Inhibition of caspase-3 by S-nitrosation and oxidation caused by nitric oxide. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997;238:387–391. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Borutaite V, Brown GC. Caspases are reversibly inactivated by hydrogen peroxide. FEBS Lett. 2001;500:114–118. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02593-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Caselli A, et al. Nitric oxide causes inactivation of the low molecular weight phosphotyrosine protein phosphatase. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:24878–24882. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lee SR, Kwon KS, Kim SR, Rhee SG. Reversible inactivation of protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B in A431 cells stimulated with epidermal growth factor. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:15366–15372. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.25.15366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kamata H, Shibukawa Y, Oka SI, Hirata H. Epidermal growth factor receptor is modulated by redox through multiple mechanisms. Effects of reductants and H2O2. Eur. J. Biochem. 2000;267:1933–1944. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Mahadev K, Zilbering A, Zhu L, Goldstein BJ. Insulin-stimulated hydrogen peroxide reversibly inhibits protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1b in vivo and enhances the early insulin action cascade. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:21938–21942. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100109200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ji C, Kozak KR, Marnett LJ. IkappaB kinase, a molecular target for inhibition by 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:18223–18228. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101266200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Korn SH, Wouters EF, Vos N, Janssen-Heininger YM. Cytokine-induced activation of nuclear factor-kappa B is inhibited by hydrogen peroxide through oxidative inactivation of IkappaB kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:35693–35700. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104321200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lander HM, Ogiste JS, Pearce SF, Levi R, Novogrodsky A. Nitric oxide-stimulated guanine nucleotide exchange on p21ras. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:7017–7020. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.13.7017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Lander HM, Ogiste JS, Teng KK, Novogrodsky A. p21ras as a common signaling target of reactive free radicals and cellular redox stress. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:21195–21198. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.36.21195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Mirza UA, Chait BT, Lander HM. Monitoring reactions of nitric oxide with peptides and proteins by electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:17185–17188. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.29.17185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Lander HM, et al. A molecular redox switch on p21(ras). Structural basis for the nitric oxide-p21(ras) interaction. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:4323–4326. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.7.4323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Yun HY, Gonzalez-Zulueta M, Dawson VL, Dawson TM. Nitric oxide mediates N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor-induced activation of p21ras. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998;95:5773–5778. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.10.5773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Molina y Vedia L, et al. Nitric oxide-induced S-nitrosylation of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase inhibits enzymatic activity and increases endogenous ADP-ribosylation. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:24929–24932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Uchida K, Stadtman ER. Covalent attachment of 4-hydroxynonenal to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. A possible involvement of intra- and intermolecular cross-linking reaction. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:6388–6393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Ravichandran V, Seres T, Moriguchi T, Thomas JA, Johnston RB., Jr S-thiolation of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase induced by the phagocytosis-associated respiratory burst in blood monocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:25010–25015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Mohr S, Stamler JS, Brune B. Posttranslational modification of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase by S-nitrosylation and subsequent NADH attachment. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:4209–4214. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.8.4209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Souza JM, Radi R. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase inactivation by peroxynitrite. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1998;360:187–194. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1998.0932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Mohr S, Hallak H, de Boitte A, Lapetina EG, Brune B. Nitric oxide-induced S-glutathionylation and inactivation of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:9427–9430. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.14.9427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Rivera-Nieves J, Thompson WC, Levine RL, Moss J. Thiols mediate superoxide-dependent NADH modification of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:19525–19531. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.28.19525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Buchczyk DP, Briviba K, Hartl FU, Sies H. Responses to peroxynitrite in yeast: glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) as a sensitive intracellular target for nitration and enhancement of chaperone expression and ubiquitination. Biol. Chem. 2000;381:121–126. doi: 10.1515/BC.2000.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Banan A, Fields JZ, Decker H, Zhang Y, Keshavarzian A. Nitric oxide and its metabolites mediate ethanol-induced microtubule disruption and intestinal barrier dysfunction. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2000;294:997–1008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Manzoni O, et al. Nitric oxide-induced blockade of NMDA receptors. Neuron. 1992;8:653–662. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90087-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Lei SZ, et al. Effect of nitric oxide production on the redox modulatory site of the NMDA receptor-channel complex. Neuron. 1992;8:1087–1099. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90130-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Lipton SA, et al. A redox-based mechanism for the neuroprotective and neurodestructive effects of nitric oxide and related nitroso-compounds. Nature. 1993;364:626–632. doi: 10.1038/364626a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Choi YB, et al. Molecular basis of NMDA receptor-coupled ion channel modulation by S-nitrosylation. Nat. Neurosci. 2000;3:15–21. doi: 10.1038/71090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Matthews JR, Wakasugi N, Virelizier JL, Yodoi J, Hay RT. Thioredoxin regulates the DNA binding activity of NF-kappa B by reduction of a disulphide bond involving cysteine 62. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:3821–3830. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.15.3821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Hayashi T, Ueno Y, Okamoto T. Oxidoreductive regulation of nuclear factor kappa B. Involvement of a cellular reducing catalyst thioredoxin. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:11380–11388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Matthews JR, Botting CH, Panico M, Morris HR, Hay RT. Inhibition of NF-kappaB DNA binding by nitric oxide. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:2236–2242. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.12.2236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.delaTorre A, Schroeder RA, Punzalan C, Kuo PC. Endotoxin-mediated S-nitrosylation of p50 alters NF-kappa B-dependent gene transcription in ANA-1 murine macrophages. J. Immunol. 1999;162:4101–4108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Marshall HE, Stamler JS. Inhibition of NF-kappa B by S-nitrosylation. Biochemistry. 2001;40:1688–1693. doi: 10.1021/bi002239y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Pineda-Molina E, et al. Glutathionylation of the p50 subunit of NF-kappaB: a mechanism for redox-induced inhibition of DNA binding. Biochemistry. 2001;40:14134–14142. doi: 10.1021/bi011459o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Abate C, Patel L, Rauscher FJ, 3rd, Curran T. Redox regulation of fos and jun DNA-binding activity in vitro. Science. 1990;249:1157–1161. doi: 10.1126/science.2118682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Nikitovic D, Holmgren A, Spyrou G. Inhibition of AP-1 DNA binding by nitric oxide involving conserved cysteine residues in Jun and Fos. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1998;242:109–112. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Klatt P, et al. Redox regulation of c-Jun DNA binding by reversible S-glutathiolation. FASEB J. 1999;13:1481–1490. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.12.1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Klatt P, Molina EP, Lamas S. Nitric oxide inhibits c-Jun DNA binding by specifically targeted S-glutathionylation. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:15857–15864. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.22.15857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Storz G, Tartaglia LA, Ames BN. Transcriptional regulator of oxidative stress-inducible genes: direct activation by oxidation. Science. 1990;248:189–194. doi: 10.1126/science.2183352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Kullik I, Toledano MB, Tartaglia LA, Storz G. Mutational analysis of the redox-sensitive transcriptional regulator OxyR: regions important for oxidation and transcriptional activation. J. Bacteriol. 1995;177:1275–1284. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.5.1275-1284.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Hausladen A, Privalle CT, Keng T, DeAngelo J, Stamler JS. Nitrosative stress: activation of the transcription factor OxyR. Cell. 1996;86:719–729. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80147-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Zheng M, Aslund F, Storz G. Activation of the OxyR transcription factor by reversible disulfide bond formation. Science. 1998;279:1718–1721. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5357.1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]