Abstract

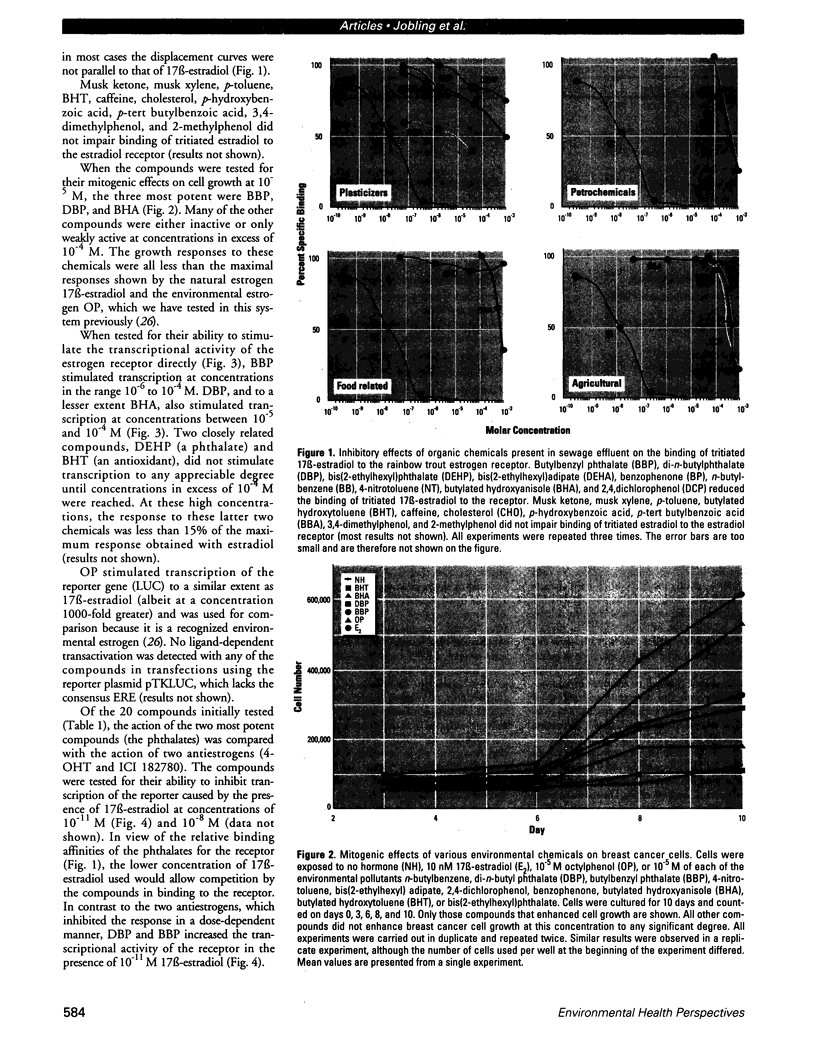

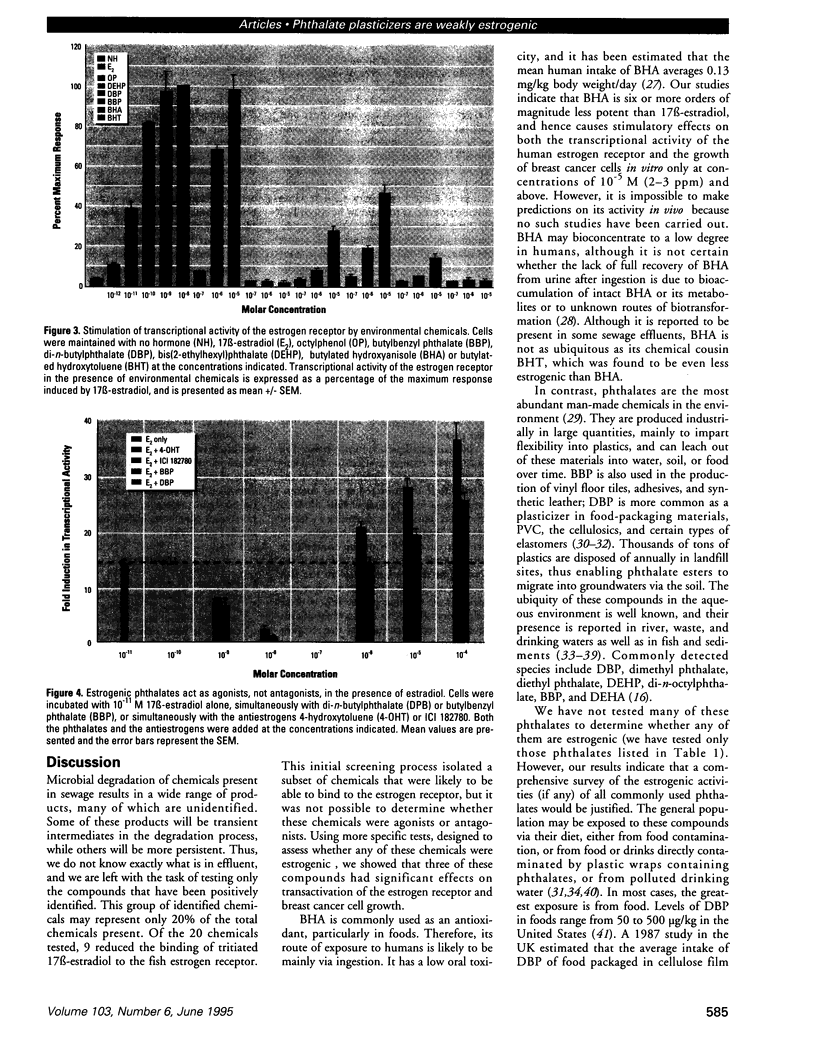

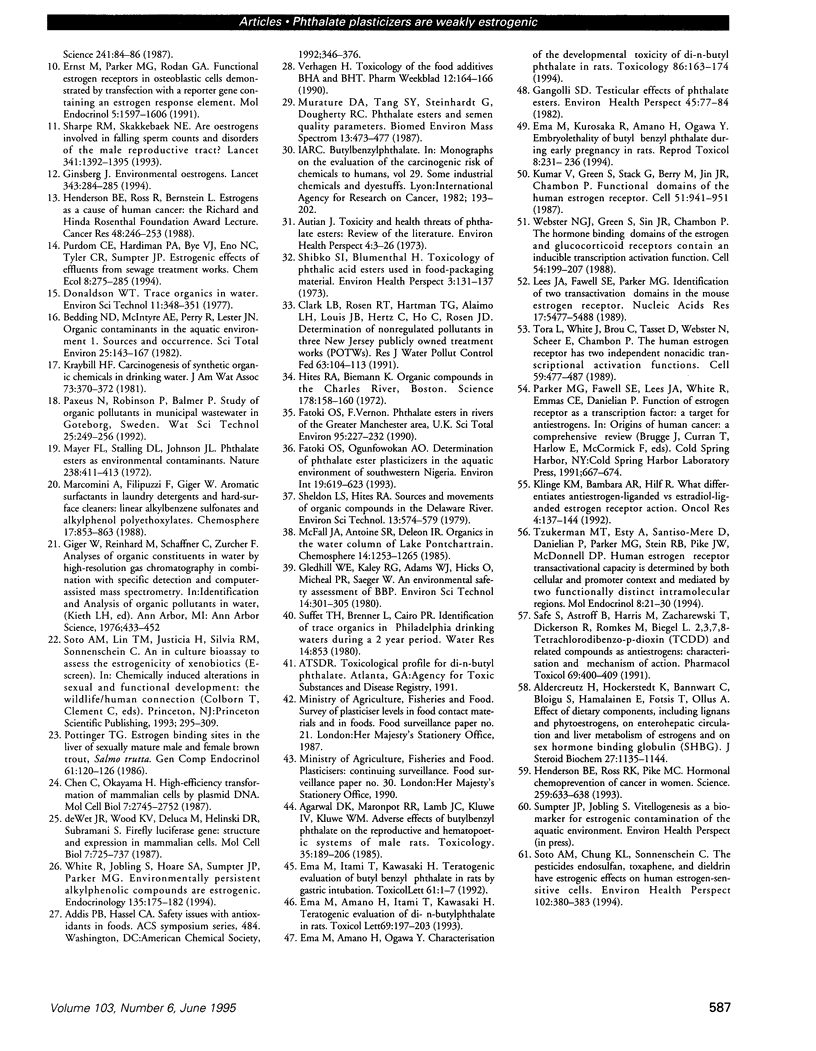

Sewage, a complex mixture of organic and inorganic chemicals, is considered to be a major source of environmental pollution. A random screen of 20 organic man-made chemicals present in liquid effluents revealed that half appeared able to interact with the estradiol receptor. This was demonstrated by their ability to inhibit binding of 17 beta-estradiol to the fish estrogen receptor. Further studies, using mammalian estrogen screens in vitro, revealed that the two phthalate esters butylbenzyl phthalate (BBP) and di-n-butylphthalate (DBP) and a food antioxidant, butylated hydroxyanisole (BHA) were estrogenic; however, they were all less estrogenic than the environmental estrogen octylphenol. Phthalate esters, used in the production of various plastics (including PVC), are among the most common industrial chemicals. Their ubiquity in the environment and tendency to bioconcentrate in animal fat are well known. Neither BBP nor DBP were able to act as antagonists, indicating that, in the presence of endogenous estrogens, their overall effect would be cumulative. Recently, it has been suggested that environmental estrogens may be etiological agents in several human diseases, including disorders of the male reproductive tract and breast and testicular cancers. The current finding that some phthalate compounds and some food additives are weakly estrogenic in vitro, needs to be supported by further studies on their effects in vivo before any conclusions can be made regarding their possible role in the development of these conditions.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Agarwal D. K., Maronpot R. R., Lamb J. C., 4th, Kluwe W. M. Adverse effects of butyl benzyl phthalate on the reproductive and hematopoietic systems of male rats. Toxicology. 1985 Jun 14;35(3):189–206. doi: 10.1016/0300-483x(85)90015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Autian J. Toxicity and health threats of phthalate esters: review of the literature. Environ Health Perspect. 1973 Jun;4:3–26. doi: 10.1289/ehp.73043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C., Okayama H. High-efficiency transformation of mammalian cells by plasmid DNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1987 Aug;7(8):2745–2752. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.8.2745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colborn T., vom Saal F. S., Soto A. M. Developmental effects of endocrine-disrupting chemicals in wildlife and humans. Environ Health Perspect. 1993 Oct;101(5):378–384. doi: 10.1289/ehp.93101378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ema M., Amano H., Ogawa Y. Characterization of the developmental toxicity of di-n-butyl phthalate in rats. Toxicology. 1994 Feb 7;86(3):163–174. doi: 10.1016/0300-483x(94)90002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ema M., Itami T., Kawasaki H. Teratogenic evaluation of butyl benzyl phthalate in rats by gastric intubation. Toxicol Lett. 1992 Jun;61(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/0378-4274(92)90057-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ema M., Kurosaka R., Amano H., Ogawa Y. Embryolethality of butyl benzyl phthalate during early pregnancy in rats. Reprod Toxicol. 1994 May-Jun;8(3):231–236. doi: 10.1016/0890-6238(94)90007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst M., Parker M. G., Rodan G. A. Functional estrogen receptors in osteoblastic cells demonstrated by transfection with a reporter gene containing an estrogen response element. Mol Endocrinol. 1991 Nov;5(11):1597–1606. doi: 10.1210/mend-5-11-1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch C. E., Felicio L. S., Mobbs C. V., Nelson J. F. Ovarian and steroidal influences on neuroendocrine aging processes in female rodents. Endocr Rev. 1984 Fall;5(4):467–497. doi: 10.1210/edrv-5-4-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangolli S. D. Testicular effects of phthalate esters. Environ Health Perspect. 1982 Nov;45:77–84. doi: 10.1289/ehp.824577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsburg J. Environmental oestrogens. Lancet. 1994 Jan 29;343(8892):284–285. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)91125-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson B. E., Ross R. K., Pike M. C. Hormonal chemoprevention of cancer in women. Science. 1993 Jan 29;259(5095):633–638. doi: 10.1126/science.8381558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson B. E., Ross R., Bernstein L. Estrogens as a cause of human cancer: the Richard and Hinda Rosenthal Foundation award lecture. Cancer Res. 1988 Jan 15;48(2):246–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hites R. A., Biemann K. Water pollution: organic compounds in the Charles River, Boston. Science. 1972 Oct 13;178(4057):158–160. doi: 10.1126/science.178.4057.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinge C. M., Bambara R. A., Hilf R. What differentiates antiestrogen-liganded vs estradiol-liganded estrogen receptor action? Oncol Res. 1992;4(4-5):137–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan A. V., Stathis P., Permuth S. F., Tokes L., Feldman D. Bisphenol-A: an estrogenic substance is released from polycarbonate flasks during autoclaving. Endocrinology. 1993 Jun;132(6):2279–2286. doi: 10.1210/endo.132.6.8504731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V., Green S., Stack G., Berry M., Jin J. R., Chambon P. Functional domains of the human estrogen receptor. Cell. 1987 Dec 24;51(6):941–951. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90581-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lees J. A., Fawell S. E., Parker M. G. Identification of two transactivation domains in the mouse oestrogen receptor. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989 Jul 25;17(14):5477–5488. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.14.5477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer F. L., Stalling D. L., Johnson J. L. Phthalate esters as environmental contaminants. Nature. 1972 Aug 18;238(5364):411–413. doi: 10.1038/238411a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murature D. A., Tang S. Y., Steinhardt G., Dougherty R. C. Phthalate esters and semen quality parameters. Biomed Environ Mass Spectrom. 1987 Aug;14(8):473–477. doi: 10.1002/bms.1200140815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker M. G. Mortyn Jones Memorial Lecture. Structure and function of the oestrogen receptor. J Neuroendocrinol. 1993 Jun;5(3):223–228. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.1993.tb00476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pottinger T. G. Estrogen-binding sites in the liver of sexually mature male and female brown trout, Salmo trutta L. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 1986 Jan;61(1):120–126. doi: 10.1016/0016-6480(86)90256-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safe S., Astroff B., Harris M., Zacharewski T., Dickerson R., Romkes M., Biegel L. 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) and related compounds as antioestrogens: characterization and mechanism of action. Pharmacol Toxicol. 1991 Dec;69(6):400–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1991.tb01321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe R. M., Skakkebaek N. E. Are oestrogens involved in falling sperm counts and disorders of the male reproductive tract? Lancet. 1993 May 29;341(8857):1392–1395. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)90953-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibko S. I., Blumenthal H. Toxicology of phthalic acid esters used in food-packaging material. Environ Health Perspect. 1973 Jan;3:131–137. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7303131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto A. M., Chung K. L., Sonnenschein C. The pesticides endosulfan, toxaphene, and dieldrin have estrogenic effects on human estrogen-sensitive cells. Environ Health Perspect. 1994 Apr;102(4):380–383. doi: 10.1289/ehp.94102380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto A. M., Justicia H., Wray J. W., Sonnenschein C. p-Nonyl-phenol: an estrogenic xenobiotic released from "modified" polystyrene. Environ Health Perspect. 1991 May;92:167–173. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9192167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tora L., White J., Brou C., Tasset D., Webster N., Scheer E., Chambon P. The human estrogen receptor has two independent nonacidic transcriptional activation functions. Cell. 1989 Nov 3;59(3):477–487. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90031-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzukerman M. T., Esty A., Santiso-Mere D., Danielian P., Parker M. G., Stein R. B., Pike J. W., McDonnell D. P. Human estrogen receptor transactivational capacity is determined by both cellular and promoter context and mediated by two functionally distinct intramolecular regions. Mol Endocrinol. 1994 Jan;8(1):21–30. doi: 10.1210/mend.8.1.8152428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster N. J., Green S., Jin J. R., Chambon P. The hormone-binding domains of the estrogen and glucocorticoid receptors contain an inducible transcription activation function. Cell. 1988 Jul 15;54(2):199–207. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90552-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White R., Jobling S., Hoare S. A., Sumpter J. P., Parker M. G. Environmentally persistent alkylphenolic compounds are estrogenic. Endocrinology. 1994 Jul;135(1):175–182. doi: 10.1210/endo.135.1.8013351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wet J. R., Wood K. V., DeLuca M., Helinski D. R., Subramani S. Firefly luciferase gene: structure and expression in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1987 Feb;7(2):725–737. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.2.725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]